Abstract

Endoscopic ultrasound is increasingly being used for evaluation of pancreatic diseases and pancreatic tumors. Among various pancreatic cystic lesions, cystic degeneration of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm is of the challenge in making diagnosis. Although unique characteristic of each type of pancreatic cystic lesions has been proposed abundantly, typical morphology of cystic degeneration of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm is still unclear. We, herein, reported a case of 66-year-old woman who was incidentally found to have a cystic lesion in the tail of pancreas upon screening transabdominal ultrasonography. A well-defined cystic lesion with rim calcification was noted on subsequent abdominal computed tomography. Endoscopic ultrasound revealed a markedly thick-wall cystic lesion containing solid nodule inside which was not enhanced following contrast-enhanced study. A mucinous cystic neoplasm was suspected and the patient was proceeded with distal pancreatectomy. A definite diagnosis of neuroendocrine neoplasm was confirmed after staining with synaptophysin and chromogranin A. We performed a meticulous review on current literatures focusing on endoscopic characteristics of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms with cystic degeneration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Following increment of medical screening program, pancreatic cystic lesions are being recognized incidentally. Initial evaluation using cross-sectional study occasionally unable to make a definite diagnosis. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is an imaging of choice that could provide detail examination and help to differentiate among various etiologies of pancreatic cystic lesions.

Case report

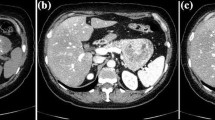

We report a case of 66-year-old woman who had no underlying medical condition. She underwent annual medical check-up which revealed an ill-defined anechoic lesion measuring 23 × 18 mm at pancreatic tail on transabdominal ultrasonography. Laboratory tests, including amylase, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA 19–9), were all within normal ranges. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen showed a round, exophytic, heterogeneous hypodensity lesion surrounding with thin wall and rim calcification on non-contrast study (Fig. 1a). On arterial and portal phase, a clear, thin-wall enhancement with cystic content was observed. Pancreatic parenchyma was unremarkable and main pancreatic duct (MPD) was not dilated (Fig. 1b, c). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in T1W fat suppression phase showed a heterogeneous hypersignal intensity inside this lesion which was suspected to contain bloody component (Fig. 2). Following initial evaluation, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) using a forward-viewing radial echoendoscope (EG-580UR, Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan) was carried out. A 24.2 × 18.5 mm cystic lesion with lateral shadowing, rather thick wall and a 9.5 mm hyperechoic nodule was observed (Fig. 3). Color Doppler and Power Doppler mode demonstrated only a small single vessel on the cystic wall. Contrast-enhanced EUS (CE-EUS) under the pulse inversion method using Sonazoid® (Daiichi-Sankyo, Tokyo, Japan) revealed distinct enhancement in the outer border of cystic wall but not in the solid nodule (Fig. 4 with VDO). Sonazoid was administered as a 0.015 mL/kg bolus together with 10 mL of saline solution over 3–5 s, and contrast-enhanced findings were observed continuously for one minute. The application of Sonazoid to the pancreas was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine. Given the gender, location and gross appearance of the lesion, mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN) was carried out as our primary differential diagnosis. Considering the malignant potential of mucinous tumor, a surgical resection by distal pancreatectomy was performed without prior cytological diagnosis. The specimen cut surface showed bloody content within uni-locular cyst surrounded with dense capsule (Fig. 5). Histology unexpectedly turned out to be a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor (Fig. 6). Confirmation with immunohistochemistry was positive for CD56, chromogranin A and synaptophysin with Ki-67 of 1% (Fig. 7). The definite diagnosis of G1 pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm with cystic degeneration was made. Patient was followed up for the next 3 months with unremarkable clinical course.

Discussion

Pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (PNENs) typically present as solid, in rare circumstance these tumors contain cystic components. Previous published studies using different imaging modalities reported 9–20% of PNENs were cystic [1,2,3]. Cystic PNENs become one of the differential diagnoses among cystic lesions of the pancreas but prevalence was far uncommon comparing with true pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCN) [4, 5]. Several theories have been put forth for the mechanism of cystic PNENs but it remains controversial [6, 7]. It is generally assumed that cystic PNENs are the result of tumor necrosis or degeneration within solid PNENs. However, conflicting data demonstrates that cystic PNENs represent a distinct entity rather than a morphologic variant as shown in one clinicopathologic study that cystic PNENs were less likely to demonstrate tumor necrosis comparing with solid PNENs (6% vs 18%) [8]. Underlying genetic etiology probably be responsible for the cystic counterparts [9]. In both solid and cystic PNENs, wide age range with no gender preference and comparable tumor size were observed. When compared with solid PNENs, cystic PNENs preferred to arise in pancreatic body and tail over pancreatic head [8]. Cystic PNENs were associated with more favorable clinic-pathological features; as they were mostly single, more often non-functional, less frequently associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 syndrome, lower histologic grading and Ki-67 proliferation index and lower risk of liver and lymph node metastasis [8, 10,11,12]. Multidisciplinary and multimodal approach were utilized to make an accurate preoperative diagnosis, yet continues to be challenging. The accuracy of preoperative diagnosis of cystic PNENs using cross-sectional imaging in distinguishing from other primary PCNs was only 47–60% [8, 13, 14]. A peripheral hypervascular rim is considered the radiologic feature most suggestive of cystic PNENs on CT or MRI. Multiple features of peripheral contrast enhancement were reported. Often smooth, thin-to-medium thickness peripheral enhancement in purely cystic or thin-to-thick thickness and focally thickened peripheral enhancement in mixed solid-cystic could be seen [15]. The peripheral enhancement in arterial phase is observed more clearly than portovenous phase. Calcification was scarcely mentioned in radiologic finding of solid pancreatic neoplasms [16] but rather referred to PCNs. While up to 25% of MCN can contain calcification [17], only 13% of predominantly cystic non-functioning PNENs represent tumor calcification [18]. Moreover, curvilinear or rim (egg-shell like) calcification, like in our case, can be found in pancreatic pseudocyst [19]. This made distinguishing calcified cystic lesions in the pancreas more complicated. Of all PNENs, calcification is usually focal, coarse, irregular, and centrally located, more commonly occurred within non-functioning and larger tumors. The appearance of rim calcification which had rarely been identified in previously reported cystic PNENs was depicted in our patient. The pathophysiology of calcification remains unclear but probably due to tumor necrosis and subsequent dystrophic calcification [20]. MRI may perform better than CT for detecting ductal communication in pancreatic cysts that usually is not considered as a cystic PNENs feature. Due to the high rate of diagnostic accuracy and low rate of complications, EUS has become an integral part of the preoperative assessment of pancreatic cysts. However, according to case series [10, 21, 22] and case reports [23, 24], cystic PNENs appear unlikely to have any unique EUS findings that are sufficient to distinguish them from other pancreatic cystic lesions. Nevertheless, cystic PNENs may include the following EUS features: either pure cystic or mixed solid-cystic component, uni-locular more frequently than multi-locular, and thicker cyst wall (> 2 mm) when compared with MCN [25]. The communication between the cyst and MPD, unlike those in intraductal papillary mucinous cystic neoplasm (IPMN), was rarely found in cystic PNENs. A single case report demonstrated high pancreatic fluid lipase level following EUS-guided aspiration which corresponded with finding of cyst-MPD connection in MRI [26]. CE-EUS showed to be beneficial over conventional EUS in evaluation of PNENs [27]. Non-enhancement area which demonstrated as filling defect could be explained by necrosis or hemorrhage inside the cyst. Our case presented the finding of clear wall enhancement with indistinct enhancing solid nodule. This could be interpreted that intracystic solid component was not a mural nodule but rather necrotic or bloody component of the lesion, reflecting degenerative change of PNEN.

Conclusion

Cystic degeneration of pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm is an uncommon etiology of pancreatic cystic lesion. Preoperative radiologic diagnosis continues to be a challenge. Variety of EUS findings were nonspecific in differentiating between cystic PNEN and PCN. We reported the rare case of cystic PNEN with rim calcification which mimicked MCN. Markedly thick cystic wall and suspicion of bloody content inside the cyst could be helpful in this diagnosis.

References

Baker MS, Knuth JL, DeWitt J, et al. Pancreatic cystic neuroendocrine tumors: preoperative diagnosis with endoscopic ultrasound and fine-needle immunocytology. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:450–6.

Figueiredo FA, Giovannini M, Monges G, et al. EUS-FNA predicts 5-year survival in pancreatic endocrine tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:907–14.

Atiq M, Bhutani MS, Bektas M, et al. EUS-FNA for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a tertiary cancer center experience. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:791–800.

Bordeianou L, Vagefi PA, Sahani D, et al. Cystic pancreatic endocrine neoplasms: a distinct tumor type? J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:1154–8.

Yamada S, Fujii T, Suzuki K, et al. Preoperative identification of a prognostic factor for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors using multiphase contrast-enhanced computed tomography. Pancreas. 2016;45:198–203.

Ahrendt SA, Komorowski RA, Demeure MJ, et al. Cystic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: is preoperative diagnosis possible? J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:66–74.

Buetow PC, Parrino TV, Buck JL, et al. Islet cell tumors of the pancreas: pathologic-imaging correlation among size, necrosis and cysts, calcification, malignant behavior, and functional status. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:1175–9.

Singhi AD, Chu LC, Tatsas AD, et al. Cystic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: a clinicopathologic study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1666–73.

Jiao Y, Shi C, Edil BH, et al. DAXX/ATRX, MEN1, and mTOR pathway genes are frequently altered in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Science. 2011;331:1199–203.

Ridtitid W, Halawi H, DeWitt JM, et al. Cystic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: outcomes of preoperative endosonography-guided fine needle aspiration, and recurrence during long-term follow-up. Endoscopy. 2015;47:617–25.

Koh YX, Chok AY, Zheng HL, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinicopathologic characteristics of cystic versus solid pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Surgery. 2014;156(83–96):e2.

Cloyd JM, Kopecky KE, Norton JA, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas: degree of cystic component predicts prognosis. Surgery. 2016;160:708–13.

Cho CS, Russ AJ, Loeffler AG, et al. Preoperative classification of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: the clinical significance of diagnostic inaccuracy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:3112–9.

Del Chiaro M, Segersvard R, Pozzi Mucelli R, et al. Comparison of preoperative conference-based diagnosis with histology of cystic tumors of the pancreas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1539–44.

Kawamoto S, Johnson PT, Shi C, et al. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor with cystlike changes: evaluation with MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:W283–90.

Ring EJ, Eaton SB Jr, Ferrucci JT Jr, et al. Differential diagnosis of pancreatic calcification. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1973;117:446–52.

Verde F, Fishman EK. Calcified pancreatic and peripancreatic neoplasms: spectrum of pathologies. Abdom Radiol (N Y). 2017;42:2686–97.

Humphrey PE, Alessandrino F, Bellizzi AM, et al. Non-hyperfunctioning pancreatic endocrine tumors: multimodality imaging features with histopathological correlation. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40:2398–410.

Li T, Chen ZQ, Meng ZX, et al. Calcified cystic lesion of the pancreas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:1272–4.

Lesniak RJ, Hohenwalter MD, Taylor AJ. Spectrum of causes of pancreatic calcifications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:79–86.

Kongkam P, Al-Haddad M, Attasaranya S, et al. EUS and clinical characteristics of cystic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endoscopy. 2008;40:602–5.

Charfi S, Marcy M, Bories E, et al. Cystic pancreatic endocrine tumors: an endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy study with histologic correlation. Cancer. 2009;117:203–10.

Colaiacovo R, de Castro AC, Ganc RL, et al. Cystic carcinoid tumor of the pancreas diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of the cystic wall: an unusual presentation and diagnosis. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2014;12:254–5.

Thorlacius H, Kalaitzakis E, Johansson GW, et al. Cystic neuroendocrine tumor in the pancreas detected by endoscopic ultrasound and fine-needle aspiration: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:510.

Yoon WJ, Daglilar ES, Pitman MB, et al. Cystic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: endoscopic ultrasound and fine-needle aspiration characteristics. Endoscopy. 2013;45:189–94.

Vitali F, Strobel D, Pfeifer L, et al. Neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas with cystic appearance mimicking a progressive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm: pitfall in medical imaging. Endoscopy. 2016;48:E302–3.

Ishikawa T, Itoh A, Kawashima H, et al. Usefulness of EUS combined with contrast-enhancement in the differential diagnosis of malignant versus benign and preoperative localization of pancreatic endocrine tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:951–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors declare that they have no competing interests and no funding was received for this case report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human rights

All procedures followed have been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for being included in the report.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kaosombatwattana, U., Hirooka, Y., Kawashima, H. et al. Neuroendocrine neoplasm of pancreas with cystic degeneration mimicking mucinous cystic neoplasm. Clin J Gastroenterol 11, 333–337 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-018-0846-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-018-0846-4