Abstract

Purpose of Review

Paracoccidioidomycosis (PCM) is one of the most prevalent systemic endemic mycosis in Latin America caused by species of an environmental fungus of the genus Paracoccidioides. In Argentina, the endemic area with the highest incidence is located in the Northeast. This review presents the current aspects of PCM epidemiology influenced by global and particular climatic anomalies.

Recent Findings

An increase of cases with particularly features, in the diagnosis and clinical manifestations, delaying the diagnosis was observed. Two genotypes of Paracoccidioides are circulating and, probably, are related to a considerable percentage of non-reactive serological tests obtained in proven cases of PCM.

Summary

The traditional view of the PCM epidemiology in the southern endemic zone area must be reconsidered. A higher level of premonition is now required in Northeast Argentina and, may be, in bordering countries. The particular characteristics both in the clinic and in the diagnosis currently observed suggest a new trend in PCM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Paracoccidioidomycosis (PCM) is a systemic disease caused by thermally dimorphic fungi of genus Paracoccidioides [1, 2••]. Although its first description was 110 years ago in 1908, by Adolpho Lutz in Brazil [3], the burden and medical importance in several countries of the endemic zone remain underestimated.

PCM is the most relevant endemic deep mycosis in Latin America, from Mexico (23° N) to Argentina (34° S) with highest incidence in South America [2••, 4, 5]; however, since PCM is not a notifiable disease, its real statistical data like prevalence and incidence remain underestimated [6•]. The World Health Organization (WHO) and organizations such as the G-FINDER project recognize several infections as neglected tropical diseases, but most fungal infections have not yet reached such status [4, 7]. Despite this, PCM is considered an endemic neglected disease in Brazil, the country with its highest incidence [1, 8].

The disease spectrum varies from oligo-symptomatic course to severe and potentially fatal disseminated disease. Infection occurs through the respiratory route by inhalation of aerosolized propagules from the saprophytic phase of the fungus (conidia and/or mycelia) resulting in an acute pulmonary disease and/or a primary pulmonary lymph node complex. Usually, in normal host, Paracoccidioides causes an asymptomatic or benign and transient pulmonary symptom; therefore, primary lesions heal spontaneously or become quiescent. Infection may progress to the acute or subacute form of the disease (frequent in children, youths, and people with immunodeficiencies) or, more commonly, reactivate afterward as a chronic form (progressive disease in adults). The asymptomatic period between infection and the onset of clinical symptoms may endure for years or decades. The lungs constituting as the primary target while all other organs represent secondary manifestations as a consequence of hematogenous spread. PCM simultaneously involves more than one organ or system and, as such, should be considered a systemic disorder [2••, 9••, 10].

PCM often remains ignored by the medical community and health systems. It eclipses by other diseases with which it shares the spectrum of clinical manifestations, such as tuberculosis and several tropical and subtropical infectious diseases, among others [8].

Until 2006, PCM was considered caused by only one species, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis (P. brasiliensis). Currently, Paracoccidioides genus comprises two species: P. brasiliensis and P. lutzii [11]. Based on whole-genome sequencing data, P. brasiliensis includes a complex of four cryptic phylogenetic species, S1, PS2, PS3, and PS4. In addition, a split of the S1 lineage in two clearly separated subclades named S1a and S1b was reported [12, 13, 14•]. In 2017, phylogenetic species of P. brasiliensis were proposed to be raised to taxonomic species status and adopt the names P. brasiliensis sensu stricto for S1, P. americana for PS2, P. restrepiensis for PS3, and P. venezuelensis for PS4 [15].

Argentina, with two endemic areas, comprises part of the southern endemic zone of PCM. One, located in the Northwest Argentina (NWA), includes only the subtropical part of Jujuy and Salta provinces. The more extensive area with the major number of reported cases is located in Northeast Argentina (NEA), bordering Brazil and Paraguay, including seven provinces or part of them: Chaco, Corrientes, Formosa, Misiones, Santiago del Estero, Santa Fé, and Entre Ríos (Fig. 1) [9••].

Current Epidemiological Status in Northeast Argentina

Clinical Features

In the last years, an increase of cases of PCM in NEA area with particular clinical and diagnosis features was observed. A wide spectrum and uncommon clinical secondary cutaneous manifestations, from disseminated papules in trunk (Fig. 2) to localized lesions, were registered (Fig. 3). Non pathognomonic lesions, without the classical lung involvement and/or the typically oropharyngeal manifestations, were described, requiring differential diagnosis even in the endemic zone with the highest incidence. In addition, an increase of neuro-PCM as cerebellar or brain abscess was detected [16]. The presentation of atypical clinical manifestations compared to those commonly observed in NEA area made the diagnosis a challenge in many cases.

Due to the inhibitory action of estrogen (β-estradiol) suppressing transformation of the saprophytic form of the fungus to yeast into the lung and also modulating the cellular immune responses, women are protected from the disease, but not from infection [10, 17]. Analyzing the last 134 PCM cases, the male:female ratio in NEA area was 18:1. The average age for women was 62 (range 50–75), and the average age for men was 51 (range 8–89). This male:female relationship is lower than previous reports from Argentina, but ratios vary in different countries, even in different geographic zones of each country and can reach values such as 70:1 in other South American countries [18,19,20,21,22]. The occurrence of PCM in women is usually associated with juvenile clinical forms of the disease or the loss of hormonal protection in menopause. All cases in NEA were postmenopausal; no younger women with PCM were registered.

In NEA, surveys with skin reactions in adults estimated infection rates ranging 10.9–20%. In contrast, only 1.6% of children and young people aged 2 to 14 years (average 10) showed previous contact with P. brasiliensis. The chronic adult clinical form has the most commonly been described in this area, and the juvenile form was always present in a very low percentage [23, 24]. Since only one case was informed in the last 15 years [25], hospital healthcare professionals from NEA had no experience in PCM in children. Despite this, from 2012, several cases in children with median of age 12 years old were reported. From severe disseminated and aggressive presentations to localized form characterized these cases of acute/subacute forms of PCM is showing a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations unusually observed in NEA area [26••]. The lack of experience about this disease in children and the wide and uncommon spectrum of manifestations observed delayed the diagnosis in some cases.

From Rural to Urban Paracoccidioidomycosis?

Considering PCM was defined as a systemic fungal infection endemic in rural areas [2••, 17], it is striking that about 40% of PCM patients from NEA referred to not live or have lived or never worked before in rural areas.

Juvenile PCM in urban areas has been described [26••, 27, 28], but also several reports rose about the urbanization of the PCM [22, 29]; moreover, a report from the western Brazilian Amazon State shows 53.6% of PCM patients lived in urban areas [18].

In the last decade, changes in the geographic and demographic patterns of the population with PCM have been informed. Factors such as the urbanization of population under unsuitable conditions favoring infection and disease at urban or suburban areas were exposed [30•]. However, it would be important to discuss and agree about the definition of an urban area in certain parts of South America; they should be well defined to be considered as such.

Challenge in Diagnosis

Visualization of the multiple budding yeasts suggestive of Paracoccidioides and the identification of the fungus by culturing clinical specimens still remain the “gold standard” for PCM diagnosis. However, reaching to the diagnosis is difficult in some cases. Quantitative immunodiffusion test (ID) represents a reliable and appropriate method to detect anti Paracoccidioides antibodies circulating. ID displays more than 80% of sensibility and 90% of specificity. Serological test is important not only for the diagnosis but also for the follow-up of host response to the treatment applied. Positivity and titers of this method depend on the immunological capacity of the patient to produce antibodies and a period ≥ 21 days from the onset of symptoms, and also correlate with the severity of the clinical form [31•].

Using antigen from the reference P. brasiliensis B339 strain, about 17% of proven PCM cases from NEA area are non-reactive to the ID test. Antigen prepared from Pb B339, rich in the immunodominant antigen glycoprotein 43 KDa (gp43) has been reported to have excellent accuracy in the diagnosis of P. brasiliensis, but low sensitivity in P. lutzii disease cases [31•]. Moreover, studies carried out in different regions of the Brazilian endemic area showed low level of concurrence using antigens from Pb B339. PCM patient sera from the Central-West Region of Brazil were unable to precipitate the reference antigen [32]. Moreover, implications of the P. brasiliensis cryptic species in the immunodiagnosis of PCM were evaluated demonstrating the variable expression of gp43 among isolates of these species and recommending to not use a single antigen preparation for serological tests [33•].

Differences observed in sensibility and specificity of ID tests using antigen from a non-autochthonous strain from NEA area may suggest differences in the antigenic composition. This highlights the importance of considering the geographical origin of the PCM cases and to know the phylogenetic Paracoccidioides species circulating in the area.

Environmental Influences

Mycosis epidemiology could be altered as a consequence of climate and environmental changes [34••]. Some studies have analyzed the conditions that stimulate not only the growth but also the survival of the fungus in the environment favoring a greater human exposure [35•, 36]. Climate changes causing an increase of soil water storage and absolute air humidity were associated with an increase of human infection rates, an increase of the incidence of PCM cases, and also with outbreaks of acute/subacute forms [26••, 30•, 37, 38, 39•].

As a consequence of certain global climatic, but also anthropogenic changes, NEA region has been undergoing ecological variations in the last decades. The influence of El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phenomenon on the incidence of PCM and apparition of clusters of acute/subacute forms was already reported [39•]. Based on the ONI index [40] during the last two decades, moderate to very strong ENSO phenomena occur in South America, raising the rainfall rates above normal ranges in NEA area.

On the other hand, the increase in the PCM cases, frequency, and infection rates has been associated to the ecological effects of hydroelectric dams [30•, 37]. The construction of Yacyretá Dam, in NEA area (see Fig. 1), altered the Paraná River valley. Yacyretá is the fourth largest dam in South America, and its impact on the rates of PCM infection was reported 20 years ago [24]. In addition, since the 1990s, deforestation and the change from the traditional cotton crop to soybean, including its particular agricultural practices, were promoted in NEA [26••].

The occurrence of PCM in youth population and children indicates early exposure to Paracoccidioides [6•]. The effect of global and particular climatic changes as contributor factors to the emergence of acute/subacute infant-juvenile PCM in NEA was recently reported [26••].

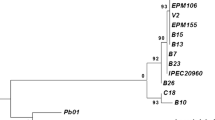

Paracoccidioides Genotypes

Recent phylogenomics analysis using whole-genome sequencing typing of 21 Paracoccidioides isolates from Argentina shows two different P. brasiliensis genotypes endemic in NEA, P. brasiliensis S1a and P. brasiliensis S1b. Even though more studies are necessary to conclude, PCM chronic form cases from NEA area were suggested they are related to P. brasiliensis S1a [41]. In this study, the reference P. brasiliensis B339 strain used to obtain antigen for ID was identified as PS3, genotype non identified between clinical isolated from NEA area.

Although implications of the cryptic species in P. brasiliensis in the immunodiagnosis have been observed, a clearer picture is still required about their ecology and their relationship with clinical manifestations, response to specific treatments, and also in diagnosis.

Conclusions

It is evident that the traditional view of the PCM epidemiology in NEA area must be reconsidered, and a higher level of premonition is now required, maybe also in bordering countries.

Global climate anomalies like ENSO phenomenon and also particular climate anomalies caused by anthropogenic changes influenced the environmental conditions that favor the human infection. The first epidemiological impact evaluated is an increase of cases of PCM with some particular clinical characteristics and the emergence of acute/subacute clinical form in children. Considering children are epidemiological markers due to having a restricted migratory profile, this fact is important to highlight. This population and its geographical sites of residence may provide significant data about epidemiological changes and probably concerning the natural habitat of Paracoccidioides.

Preliminary studies in molecular epidemiology show two Paracoccidioides genotypes circulating in NEA and differences from the reference B339 strain used for ID test. Although the clinical impact was not still evaluated, the genetic divergence reported in the genus Paracoccidioides and its implications should be considered. Geographic limits in the use of exoantigens for PCM diagnosis reported emphasize the requirement to improve the strategies, such us using exoantigens produced by autochthonous strains in order to enhance the serological test sensibility.

The particular characteristics both in the clinic and in the diagnosis currently observed suggest a new trend in PCM.

Undoubtedly, the human resources training in mycology for a long time promoted in Argentina allows us to know this current epidemiological situation of the PCM. More mycologists in NEA area are improving the diagnosis.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Mendes RP, Cavalcante RS, Marques SA, Marques MEA, Venturini J, Sylvestre TF, et al. Paracoccidioidomycosis: current perspectives from Brazil. Open Microbiol J. 2017;11(1):224–82. http://benthamopen.com/FULLTEXT/TOMICROJ-11-224.

•• Restrepo A, Gómez BL, Tobón A. Paracoccidioidomycosis: Latin America’s own fungal disorder. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2012;6(4):303–11. This is a comprehensive review of PCM epidemiology in Latin America.

Lutz A. Trabalhos sobre dermatologia e micologia. Bras Med. 1908;22:121–4. http://www.bvsalutz.coc.fiocruz.br/lildbi/docsonline/pi/textos/Micose-pseudococcidica-localizada-na-boca-e-observ.pdf.

Falci R, Queiroz-Telles F, Fahal AH, Falci DR, Caceres DH, Chiller T, et al. Neglected endemic mycoses. Ser Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(17):30443–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30306-7.

Colombo AL, Tobón A, Restrepo A, Queiroz-Telles F, Nucci M. Epidemiology of endemic systemic fungal infections in Latin America. Med Mycol. 2011;49(8):785–98.

• Restrepo A, McEwen JG, Castañeda E. The habitat of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis: how far from solving the riddle? Med Mycol. 2001;39(3):233–41. This is a review article about the ecology of Paracoccidioides and its relationship with certain PCM characteristics.

WHO | World Health Organization Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases. Neglected tropical diseases. World Health Organization; 2018 [cited 2018 Jul 13]. http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/diseases/en/.

Martinez R. Paracoccidioidomycosis: the dimension of the problem of a neglected disease. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2010;43(4):480. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0037-86822010000400034&lng=en&tlng=en.

•• Negroni R. Paracoccidioidomycosis (South American blastomycosis, Lutz’s mycosis). Int J Dermatol. 1993;(12):847–59. This article is a review about epidemiology, pathogenesis and clinical aspects of PCM.

Travassos LR, Taborda CP, Colombo AL. Treatment options for paracoccidioidomycosis and new strategies investigated. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2008;6(2):251–62.

Teixeira Mde M, Theodoro RC, Oliveira FF, Machado GC, Hahn RC, Bagagli E, et al. Paracoccidioides lutzii sp. nov.: biological and clinical implications. Med Mycol. 2014;52(1):19–28.

Matute DR, McEwen JG, Puccia R, B a M, San-Blas G, Bagagli E, et al. Cryptic speciation and recombination in the fungus Paracoccidioides brasiliensis as revealed by gene genealogies. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23(1):65–73. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16151188.

Teixeira MM, Theodoro RC, Nino-Vega G, Bagagli E, Felipe MSS. Paracoccidioides species complex: ecology, phylogeny, sexual reproduction, and virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(10):e1004397. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4214758&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

• Muñoz JF, Farrer RA, Desjardins CA, Gallo JE, Sykes S, Sakthikumar S, et al. Genome diversity, recombination, and virulence across the major lineages of Paracoccidioides. mSphere. 2016;1(5):e00213–6. This article summarizes the phylogeny and current taxonomy of Paracoccidioides genus.

Turissini DA, Gomez OM, Teixeira MM, McEwen JG, Matute DR. Species boundaries in the human pathogen Paracoccidioides. Fungal Genet Biol. 2017;106:9–25. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28602831.

Giusiano G, Cattana ME, Tracogna MF, Sosa MA, Rojas F, Fernández MS, et al. Re-emerging paracoccidioidomycosis in Argentina with peculiarities in the diagnosis and clinical manifestations. Mycoses. 2015;58(Suppl4):124–5.

Shankar J, Restrepo A, Clemons KV, Stevens D a. Hormones and the resistance of women to paracoccidioidomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24(2):296–313.

de Deus Vieira G, da Cunha Alves T, de Lima SMD, Camargo LMA, de Sousa CM. Paracoccidioidomycosis in a western Brazilian Amazon state: clinical-epidemiologic profile and spatial distribution of the disease. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47(1):63–8. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0037-86822014000100063&lng=en&tlng=en.

Dutra LM, Silva THM, Falqueto A, Peçanha PM, Souza LRM, Gonçalves SS, et al. Oral paracoccidioidomycosis in a single-center retrospective analysis from a Brazilian southeastern population. J Infect Public Health. 2018;11(4):530–3. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1876034117302848.

Negroni P, Negroni R. Paracoccidioidomicosis. In: Negroni P, Negroni R, editors. Micosis cutáneas y viscerales. 9th ed. Buenos Aires: Lopez Libreros Editores; 1991. p. 156–64.

López-Martínez R, Hernández-Hernández F, Méndez-Tovar L, Manzano-Gayosso P, Bonifaz A, Arenas R, et al. Paracoccidioidomycosis in Mexico: clinical and epidemiological data from 93 new cases (1972–2012). Mycoses. 2014;57(9):525–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/myc.12190.

Blotta MH, Mamoni RL, Oliveira SJ, Nouér SA, Papaiordanou PM, Goveia A, et al. Endemic regions of paracoccidioidomycosis in Brazil: a clinical and epidemiologic study of 584 cases in the southeast region. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61(3):390–4.

Mangiaterra M, Alonso J, Galvan M, Giusiano G, Gorodner J. Histoplasmin and paracoccidioidin skin reactivity in infantile population of northern Argentina. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1996;38(5):349–53.

Mangiaterra ML, Giusiano GE, Alonso JM, Gorodner JO. Paracoccidioides brasiliensis infection in a subtropical region with important environmental changes. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1999;92(3):173–6.

Taicz M, Rosanova MT, Bes D, Lisdero ML, Iglesias V, Santos P, et al. Paracoccidioidomycosis in pediatric patients: a description of 4 cases. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2014;31(2):141–4.

•• Giusiano G, Aguirre C, Vratnica C, Rojas F, Corallo T, Cattana ME, et al. Emergence of acute/subacute infant-juvenile paracoccidioidomycosis in Northeast Argentina: effect of climatic and anthropogenic changes? Med Mycol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/mmy/myx153 http://academic.oup.com/mmy/advance-article/doi/10.1093/mmy/myx153/4807357. This study conducted in Northeast Argentina provides information about the emergence of a cluster of PCM in children influenced by climatic anomalies.

Carneiro Rda C, Miranda BG, Camilo Neto C, Tsukumo MK, Fonseca CL, Mendonca JS. Juvenile paracoccidioidomycosis in urban area: report of two cases. Braz Infect Dis. 2010;14:77–80.

Ballesteros A, Beltrán S, Patiño J, Bernal C, Orduz R. Paracoccidioidomicosis juvenil diseminada diagnosticada en una niña en área urbana. Biomedica. 2014;34:21–8.

de Macedo PM, Almeida-Paes R, Freitas DFS, Varon AG, Gomes Paixao AG, Rocha Romao AR, et al. Acute juvenile Paracoccidioidomycosis: a 9-year cohort study in the endemic area of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(3):e0005500.

• Martinez R. New trends in Paracoccidioidomycosis epidemiology. J Fungi. 2017;3(1):1 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5715958/. This article evaluates PCM data in Latin America and the possible causes of epidemiological modification.

• Shikanai-Yasuda MA, Mendes RP, Colombo AL, De Q-t F, Satie A, Kono G, et al. Brazilian guidelines for the clinical management of paracoccidioidomycosis. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2017;50(5):715–40. This article summarizes the current recommendations for the management of PCM according to the Brazilian Society of Infectious Diseases.

Batista J Jr, de Camargo ZP, Fernandes GF, Vicentini AP, Fontes CJF, Hahn RC. Is the geographical origin of a Paracoccidioides brasiliensis isolate important for antigen production for regional diagnosis of paracoccidioidomycosis? Mycoses. 2010;53(2):176–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01687.x.

• Machado GC, Moris DV, Arantes TD, LRF S, Theodoro RC, Mendes RP, et al. Cryptic species of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis: impact on paracoccidioidomycosis immunodiagnosis. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2013;108(5):637–43. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0074-02762013000500637&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en. This work evaluates the implications of cryptic species in P. brasiliensis in the immunodiagnosis.

•• Martinez R. Epidemiology of paracoccidioidomycosis. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2015;57(suppl 19):11–20 http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0036-46652015000800011&lng=en&tlng=en. This article review clinical and epidemiological aspects of PCM and the geographic distribution in Latin America.

• Barrozo LV, Mendes RP, Marques SA, Benard G, Siqueira Silva ME, Bagagli E. Climate and acute/subacute paracoccidioidomycosis in a hyper-endemic area in Brazil. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(6):1642–9. This work help to clarify the conditions that favor Paracoccidioides survival and growth in the environment and enhance human exposure.

Simões LB, Marques SA, Bagagli E. Distribution of paracoccidioidomycosis: determination of ecologic correlates through spatial analyses. Med Mycol. 2004;42(6):517–23.

Loth EA, De CSV, Da SJR, Gandra RF. Occurrence of 102 cases of paracoccidioidomycosis in 18 months in the Itaipu Lake region, Western Paraná. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2011;44(5):636–7.

Coimbra Júnior CE, Wanke B, Santos RV, do Valle AC, Costa RL, Zancopé-Oliveira RM. Paracoccidioidin and histoplasmin sensitivity in Tupí-Mondé Amerindian populations from Brazilian Amazonia. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1994;88(2):197–207 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8067815.

• Barrozo LV, Benard G, Silva MES, Bagagli E, Marques SA, Mendes RP. First description of a cluster of acute/subacute paracoccidioidomycosis cases and its association with a climatic anomaly. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(3):e643. This article describe the relationship between clusters of PCM cases with the climatic anomaly caused by El Niño Southern Oscillation.

Null J. El Niño and La Niña years and intensities based on Oceanic Niño Index (ONI). 2017. [cited 2018 Jul 15]. Available from: http://ggweather.com/enso/oni.htm.

Cattana ME, Teixeira MDM, Litvintseva A, Tracogna MF, Arechavala A, Negroni R, et al. Whole genome sequencing of P. brasiliensis isolates of endemic areas in Argentina and Paraguay. Med Mycol. 2018;56(suppl2):S1–159. https://academic.oup.com/mmy/article/56/suppl_2/S1/5033473.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Clinical Mycology Lab Issues

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giusiano, G., Rojas, F., Mussin, J. et al. The Southern Endemic Zone of Paracoccidioidomycosis: Epidemiological Approach in Northeast Argentina. Curr Fungal Infect Rep 12, 138–143 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12281-018-0324-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12281-018-0324-y