Abstract

German companies have recently faced criticism that they tend to lag behind in terms of corporate social responsibility (CSR) compared to their European counterparts. German consumers and its society at large, however, are getting more conscious about the socially responsible behavior of companies and therefore demand responsible management. To meet this demand, educational institutions need to train future employees and leaders to carry out business in a socially responsible way. It is thus important for CSR to form an integral part of the core values and curricula in educational institutions, where the younger generation gains theoretical and practical knowledge. In our examination of CSR education in Germany and its impacts, we use results from expert interviews with German CSR faculty members as well as the case study of Koblenz University of Applied Sciences, RheinAhrCampus. In our study, we found that CSR education influences university students’ perception of CSR in businesses, but their private attitudes on consumption and employment tend to stem from their own inherent understanding of social responsibility. We conclude that having more CSR ambassadors as faculty members in universities is one way of moving forward with CSR education in Germany.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Business Ethic

- Business School

- Mission Statement

- Corporate Social Responsibility Activity

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

Recent studies have found German companies to lag behind in terms of corporate social responsibility (CSR) compared to their European counterparts (Antal, Oppen, & Sobzca, 2009; Silberhorn & Warren, 2007). CSR activities are not only less publicly reported in German companies, but commitment to CSR tends to be missing from corporations’ official mission statements and strategies. These findings come as a surprise as Germany was seen as the economic motor of Europe during the financial crisis and would be expected, as a consequence, to take a leading role in developing good practice examples for CSR in Europe. Yet, a Europe-wide survey conducted by the German Manager Magazin found that German companies could do better in CSR as they are being edged out by British, Finnish, and Swiss companies (Kröher, 2005).

In this study, five teams of experts evaluated the companies based on publicly available reports, which included financial reporting, sustainability reporting, and CSR reports. Companies were given points based on their social responsibility to:

-

employees (compensation, staff development etc.)

-

society (orientation of commitment to society as part of the corporate strategy, anchoring of CSR programs in business, degree of social engagement, and social awareness of the issues of the CSR programs), and

-

the environment (e.g. environmental aspects of the value chain, eco-innovation, integration of environmental aspects into business processes).

They were also given points based on their financial strength (equity ratio, shareholder return, growth and volatility of cash flow etc.) and the transparency of their internal and external processes. The points awarded resulted in a “Good Company” ranking. Out of the top five firms in the list, four had British origins—namely BP, Anglo American, British Telecom, and Royal Dutch Shell. While four out of the top ten companies in the Good Company Ranking list were German (Deutsche Post, Deutsche Telekom, BASF, and Henkel), German companies could rank even better if they systematically integrated CSR into their operations.

A similar study conducted by Deloitte (2009) among 55 large companies of the consumer goods and retailing industry in Germany showed that there is, indeed, very low integration of management control departments in activities related to corporate sustainability. In addition, a comparative study that is based on a qualitative content analysis of the CSR websites of 40 British and German companies, and a series of interviews with senior managers, also preliminarily concluded that British companies tend to be clearer and broader in their public definition of CSR than German companies (Silberhorn & Warren, 2007). Compared to German companies, British companies included more CSR themes, such as corporate governance and compliance with the law, risk management processes, health and safety management, corporate benchmarking, and employee community involvement. In the study, the British companies interviewed mentioned these themes more often than their German counterparts (Silberhorn & Warren, 2007). This finding indicates that German companies could benefit more from demonstrating a broader, more business-driven understanding of CSR.

Antal et al. (2009) pointed out that while companies in Germany have had a long history of practicing some kind of social responsibility, the actual concept of CSR as a formalized business strategy is relatively new and not established as an integral part of the recognized corporate image. Indeed, according to the analysis by Kraus and Britzelmaier (2012), German corporations tend to engage in a defensive approach when it comes to CSR—a strategy deemed to be less proactive as compared to the cost-benefit, strategic, and innovation and learning approaches (Zadek, 2004). In other words, German companies have a tendency to engage in CSR only to reduce the feared risks that may be associated with potential scandals or negative reports about unethical business practices, instead of embracing CSR as a proactive approach to generate new markets.

In contrast to these reports about the relatively conservative approach of large companies to CSR, consumers in Germany seem to be more knowledgeable in this area. A cross-cultural study on consumers’ perceptions of CSR showed that German consumers tend to place high importance on companies’ ethical conduct (Maignan, 2001). A study by Maignan (2001) found that German consumers placed legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibilities above economic responsibilities. Consumers are more concerned that businesses conform to social and ethical norms instead of achieving high levels of economic performance. With this apparent discrepancy between observed conservative business strategies and more evolved consumer preferences, incorporating CSR in education, especially in business schools, becomes increasingly important for several reasons.

First, CSR education increases students’ awareness of local and global ethical issues such as employee and human rights, voluntary engagement in civic activities, and international sustainability standards. This heightened awareness would not only challenge and influence students’ private consumption attitudes, but is also likely to affect their overall decision-making processes once they hold a managerial position in a company in their later careers. Second, as future employees and managers in German companies, students need to understand the role of CSR as a strategic expansion strategy, where active engagement in CSR provides new opportunities for employees to learn and develop, as well as for organizations to increase their market presence (Buchholtz & Caroll, 2008). In order to achieve these goals, German companies need to change the current status of CSR and incorporate CSR activities as a key performance indicator (KPI). By gaining theoretical and practical knowledge of CSR during their formal education in universities, students will be able to help their future companies move closer to this goal.

This chapter examines the impact of CSR education in Germany. In order to provide a comprehensive view of the topic, we divide the chapter into three sections. In the first section, we analyze the current status of CSR education in German universities, as well as analyze the German view on CSR education by examining how leading German CSR experts and faculty approach CSR education in business schools and universities worldwide. In order to accomplish this, we use results from a qualitative and quantitative study with five German faculty teaching CSR in business schools. In the second section, we analyze the state of CSR education in a particular university in Germany, namely Koblenz University of Applied Sciences. We do this by examining the mission statement, syllabi, and curricula of the university, as well as by examining the university’s CSR-related activities. In the third section, we use results from a quantitative study from K oblenz University of Applied Sciences. We examine the impact of CSR education on students’ perceptions of CSR in businesses, as well as on their private consumption and prospective employee attitudes.

2 CSR Education in Germany

2.1 Role and Responsibilities of Business Schools and Faculty

Despite the often-aired argument that “ethics cannot be taught”, education in CSR and business ethics remains essential (Piper, Gentile, & Parks, 1993). As courses in leadership and marketing do not necessarily produce outstanding leaders or brand managers, education in CSR may not always produce “better people”. However, the fact that society recognizes that these aspects are important in education means that perhaps, social responsibility should be taught in core courses in business schools (Rasche, 2011).

According to the study by Schwerk (2010) with 287 German universities, 60 % of German business schools currently have lectures related to the broader topic of CSR. Most of the CSR courses offered are related to business topics, such as management and sustainable marketing. Still, the study found that CSR education is integrated in other topics as well such as courses on renewable energy, eco-controlling, and sustainable tourism (Schwerk, 2010). This seems to suggest that CSR education in Germany is rather well established.

However, we are interested in the actual implementation process, analyzing if the structure of the curricula and courses correspond to effective CSR education. In particular, we are interested in whether the content and topics taught in CSR courses are successfully conveyed to and understood by students. There has been much attention on CSR education from a macro level, that is, examining university-level variables such as mission statements, implementation instruments, and curricula. In this chapter, we attempt to provide a more holistic view of CSR education in Germany, by adding a micro-level perspective, where we examine how the faculty of business schools approach CSR education.

In order to do that, we refer to an ongoing cross-cultural empirical study conducted by Reifferscheid and Heinzen (2015), which analyzes CSR education from a macro and micro level perspective in business schools in Europe and North America. In total, 53 CSR-related courses were analyzed, and five faculty members from five different universities were interviewed for this study. We focus on how leading German CSR experts in academia (research and education) view and approach social responsibility education. Although they are of German nationality, the five selected experts also work and teach at leading business schools abroad. In total, we evaluate analyses from one German university and four universities from Canada, Denmark and Switzerland.

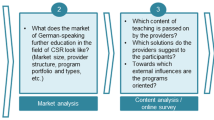

2.2 Overview of Study

We will present the results of the Reifferscheid and Heinzen (2015) study. Data were gathered in two ways. First, a series of semi-structured guided expert interviews were conducted. Second, the mission statements, implementation instruments, and curricula available from the web pages of the business schools were analyzed. All of the business schools provided official and public access to curricula and syllabi. The existence, relevance and implementation of values-oriented mission statements, as well as related instruments and the design of the CSR curricula, were examined. We first discuss the macro-level findings and then delve into the micro-level results, based on the combination of public data and responses from the expert interviews.

2.3 Macro Level: CSR Education in Business Schools and Universities

2.3.1 Mission Statements

For this study, mission statements were taken from data available from the universities’ websites. All mission statements were analyzed with regard to their general structure and content (Sidhu, 2003), philosophy, the business school’s core competencies and values orientation. All of the mission statements followed similar structures, but showed differences in terms of “what to achieve through what”.

The underlying notion that educating or developing future leaders through the combination of the business school’s core competencies, such as knowledge, research, and teaching, was shared by all business schools. They do, however, differ in the means in which they believe future leaders as individuals should be developed, revealing a variety of attributes and capabilities they deem important for leaders. Examples of these attributes and capabilities include integrative and critical thinking, effectiveness, and entrepreneurial behavior. These examples have a unifying factor in that they all stress the development of ethical leadership, as they represent important aspects of individual reflection and are also connected to the concept of responsibilities and values. In this sense, the values-oriented mission statements in business schools correspond to the overall societal need for responsible management education to groom future leaders who will be able to make ethical business decisions.

2.3.2 Implementation Instruments

The development and publication of a mission statement is an important part of a mindful and self-reflected process. However, putting into practice the theoretical ideas to address the “gap between rhetoric and reality” (Rasche, Gilbert, & Schedel, 2012) is the real challenge for any organization. While both the perceived and actual linkage between the activities of the business schools and their corresponding mission statements highlight the importance of a well-considered and precisely formulated mission statement (Cornelius, Wallace, & Tassabehji, 2007), business schools have a variety of opportunities or instruments that can serve to strengthen that linkage.

Implementation ranges from “faculty-only” to institution-wide variations, which include students and other staff. For example, as far as “pledges” or “beliefs” are concerned, students are required to sign and agree to them at the beginning of and during the course of their studies. These sort of pledges include the commitment to not carry out acts of misconduct, such as plagiarism and cheating. These documents aim to sensitize students to ethical behavior. In some instances, students are advised to report acts of misconduct they may have observed in other students or staff to dedicated internal sections.

The development of specific communities and project groups that deal with community work, social learning or entrepreneurship projects, and other types of group engagement, represents another type of CSR instrument or initiative found in business schools. They are very present in the everyday life of the business schools selected in this study. By emphasizing the actual engagement of socially responsible activities, these initiatives not only make ethical issues more comprehensible to students, but they also help sensitize students to their individual and collective responsibilities.

2.3.3 Curricula

The curricula and syllabi of the selected business schools in our study were screened, and the content was analyzed by employing keywords. The courses were also differentiated between stand-alone and integrated courses, as well as between mandatory and elective course offers. Stand-alone courses refer to modules that are entirely dedicated to CSR or business ethics, such as examining the multiple stakeholders of a company and how it deals with these responsibilities. Integrated courses refer to modules which mainly cover a different business topic (e.g. marketing, leadership etc.), but include CSR aspects into their list of topics treated. Table 1 represents the results of the 53 courses that were offered at the selected business schools across all ranges of studies and levels of graduation.

The figures from Table 1 allow the following interpretations: First, at the beginning of students’ education (i.e. undergraduate), a high number of integrated courses assure that within their ranges of studies, students are confronted with ethical issues and their relevance in a broader context. Even when taking courses that are not explicitly related to CSR, the younger generation is made aware of “what to expect in their future work life”, namely, that ethics and social responsibility will always play a role in the workplace. It is also interesting to note that at the undergraduate level, a wide variety of courses are offered on an elective basis.

Second, we observe that CSR education tends to be more developed at the executive level. Mandatory stand-alone courses are preferred in order to allow the groups to reflect on “what they have already experienced in their work life”. Executives learn to deal with basic ethical and philosophical theories and models, at the same time as they are experiencing ethical issues and dilemmas in their own workplace. It appears that in these business schools, ethical decision-making competencies tend to be more rigorously developed only at a more advanced stage of education.

To summarize the results of the curriculum analysis, the implementation of ethics-related courses at the selected business schools: (i) is cross-disciplinary, (ii) is done across all levels of graduation (undergraduate/graduate/executive), (iii) has a mixed selection of integrated and stand-alone courses, and (iv) includes both mandatory and elective courses. Findings suggest that in undergraduate education, preference is being given to a higher proportion of integrated and elective courses as opposed to mandatory stand-alone courses in graduate and executive education.

2.4 Micro Level: Faculty’s View on CSR Education

As faculty members are those responsible in training and developing socially responsible employees who will grow into ethical future leaders (Gruber & Schlegelmilch, 2013), it is important to examine their individual competencies and embodiment of CSR education. With regard to the faculty’s individual understanding of their roles and responsibilities, analysis of the transcribed interviews with leading German CSR experts led to the summarized development of different roles and teaching methods of ethics educators described in the subsequent sections. From the expert interviews, we developed a typology, differentiating between the role of the faculty member as an educator, moderator, and ambassador. We also examine the variety of teaching methods or pedagogical approaches of the experts in our study.

2.4.1 The Roles of the Educator, Moderator, and Ambassador

A social responsibility educator needs to deliver an underlying theoretical framework for ethical theories and their historical development within an ethics-related course, in the form of providing specific skills and tools. However, it is also important to put these aspects in a broader social context, referring to (inter)cultural and historical, and systemic perspectives of society. This approach leads to the second faculty role of the moderator, who should neither preach nor teach right or wrong behavior, but should sensitize individual awareness through facilitating changes of perspectives in learners, such as when dealing with case studies of misconduct in the real business world.

When students take on the role of the “CEO”, e.g. in a simulated company or in counterpart-discussions, and are responsible for any kind of misconduct that impacts others, they can at least get a sense of what such situations of ethical dilemma can feel like in the real working world. For this approach, the pedagogical perspective needs to shift from teacher-centric to learner-centric experiential learning. Moderators have to limit their roles to that of the facilitator who merely organizes and manages learning opportunities (Borgmann, 2009). Moderating these role plays and discussions through thought-provoking situational activation or vitalization is key to learners’ reflection processes. In this sense, the faculty’s roles are primarily about raising awareness and encouraging reflection, while providing knowledge, skills, tools, and conducive learning opportunities to students.

The third role, ambassador, focuses on a more internal view of the faculty members’ perceptions of their own roles. As an ambassador, the faculty should be an active and leading part in the process of the identification and sharing of common values and beliefs within the business school, and present themselves as role models for the institutionalization and internalization of “responsible behavior”. In order to develop and extend the practical aspect of CSR education, faculty members can cooperate with corporate members and the society by engaging in social and community projects, or by inviting practitioners as guest speakers. In this way, faculty members are able to integrate the external views of their role obligations (educator and moderator) with the internal view of their individual understanding of their role (ambassador).

2.4.2 Pedagogical Approaches

When asked about what types of pedagogical approaches they apply, the majority of the faculty and CSR experts in this study reported themselves as being more in the role of an educator rather than a teacher. This may be a reflection of the long tradition of the holistic concept of education in German society. The educator provides a space in which students can gain awareness of the individual and collective reflection on ethical dilemmas, and where they can reflect upon the ways in which such situations should be handled. Creating an open-minded, yet thought-provoking, learning atmosphere within courses is deemed crucial for attaining these objectives.

Faculty members were also asked how they typically respond to the situation in the classroom when students have different views on values or responsibilities. They answered that these situations are more than welcome in classroom discussions, as they offer opportunities for reflection and change of perspectives which form an important aspect of CSR education. Besides, faculty members do not aim to deliver a “sample solution”, but rather, to develop students’ individual competencies in establishing and defending their different points of view, while respecting the opinions of others.

In stand-alone courses, focus is on ethical theories, the process of ethical decision-making, and the historical development of business ethics and CSR. Integrated courses usually include a higher degree of practical applications, where examples used in class include real business cases and the everyday situations in the workplace. By closely examining case studies, students are trained in adopting different positions, as they view the issue through multiple perspectives via counter-part discussions. In exercises such as writing hypothetical “Letters to CEOs” of companies involved in scandals, students can apply the theoretical knowledge gained in the courses to the practical context of introducing change.

2.5 Discussion

Business schools, like any other organization, can and should base their behavior on underlying values in a thoughtful way in order to fulfill their inherent responsibilities and obligations. The development of a written mission statement referring to ethical and values-oriented content, in addition to being able to develop and implement action, is the initial step for bringing words to life and having a positive impact on members of the organization (Davis, Ruhe, Lee, & Rajadhyaksha, 2007; McCabe, Trevino, & Butterfield, 2002). Strengthening the linkage between espoused and actual behavior, mission statements not only need to incorporate socially responsible values, but also set a basis for activities and instruments that foster ethical awareness (Cornelius et al., 2007). In order to internalize the mission statement’s values and beliefs, instruments such as codes of conduct, codes of honor, or pledges and beliefs need to be accompanied by operational practices in order to be taken seriously by business students (Desplaces, Melchar, Beauvais, & Bosco, 2007) and faculty alike (McCabe, Butterfield, & Trevino, 2006).

A well-balanced design of a CSR curriculum including challenging ethical classroom discussions is the most effective way to teach business students about socially responsible behavior and ethical decision-making processes. The results from our study suggest that business schools should strive for a fully integrated approach that involves stand-alone CSR courses, delivering basic theoretical input combined with practical case studies to develop students’ abilities in dealing with and resolving ethical dilemmas (Swanson & Fisher, 2008; Trevino & Nelson, 2010).

Faculty members involved in CSR education act as role models for students and should therefore also be sensitized in their respective discipline, e.g. within the doctoral program (Giacalone & Thompson, 2006; Mitchell, 2007; Rasche et al., 2012). The faculty is perceived as the driving agent for the university in translating macro-level values to micro-level engagement in CSR. With a clear understanding of their own ethical values, faculty members can teach CSR with conviction and passion, infusing their ethical direction into the different components of the coursework.

3 CSR Education in Koblenz University of Applied Sciences, RheinAhrCampus

For this chapter, the chosen university in Germany is the Koblenz University of Applied Sciences, RheinAhrCampus due to convenience sampling. RheinAhrCampus is a young and modern campus located in the north-west region of Germany. Founded in 1998, the campus has since expanded to include 2800 students. RheinAhrCampus consists of two faculties—Mathematics & Technology and Business & Social Sciences (RheinAhrCampus, 2015).

3.1 Mission Statement

As in the previous cross-cultural study, we examined the mission statement, the implementation instruments, and the curriculum of the university to obtain a macro-level perspective of CSR education. Analyzing the profile and mission statement of the campus, we found that CSR is emphasized through international projects and collaborations with external institutions, as well as through practical role plays and simulations.

3.2 Implementation Instruments

RheinAhrCampus is committed to being the regional center for innovation which carries out applied research and development. It does so through collaborations with the region’s service providers, institutions, and companies. At the local level, engagement in research and development for the betterment of society, while working hand in hand with German enterprises, represents a facet of CSR. The implementation instruments available in RheinAhrCampus include the Social Responsibility Education in Europe Project, which is an initiative aimed at developing joint CSR course content for European universities, lecturers, and students. Knowledge, expertise, and experience of 12 universities are shared in conferences and intensive seminars in Izmir, Turkey, and Remagen, Germany, resulting in the development of a new curriculum and joint learning methods, materials, and techniques.

There are also projects that encourage the integration of information technology (IT) into learning at the university, in order to empower students to work competently in the digital world. These projects, such as UnderstandIT, VITAE-project, GameIT, and Columbus Portal, not only train students in optimizing their learning methods with the use of information technology, but the fact that these projects are also collaborations with external institutions support the spirit of implementing CSR at a wider level. In these projects, students work closely with external organizations in effecting change as some courses (e.g., International Business Simulations) require them to carry out CSR projects with real companies and local institutions (Borgmann & Kokareva, 2014).

3.3 Curricula

We examined the curriculum and conducted similar analyses as the previous study with regard to the classification of courses. We sifted through the list of courses offered in the faculty of Business and Social Sciences and coded if CSR or business ethics is a core concept in the syllabi, or if it is a topic that is integrated into cross-disciplinary courses. We also analyzed if the CSR and CSR-related courses are compulsory for students, or if they can participate in them voluntarily. Table 2 shows the breakdown of CSR and CSR-related courses according to whether they are stand-alone or integrated courses, and whether they are mandatory or elective.

As concluded by the previous study, there are more elective courses at the undergraduate level, and there is a higher proportion of mandatory courses at the graduate level. However, different from the findings of the study by Reifferscheid and Heinzen (2015), there are more stand-alone courses at the undergraduate level, whereas at the graduate and executive level, CSR education tends to take the form of integrated courses. There is a rich variety with 28 different CSR-related courses being offered at RheinAhrCampus. The availability of these courses indicates that the university as a whole is carrying out the espoused behavior of providing CSR education to students. This is similar to the finding by Schwerk (2010), in that business schools in Germany do offer courses in CSR. However, as most of the courses in this university are offered on an elective basis, not all students will be equally exposed to CSR education.

4 Impact of CSR Education on Students

4.1 Overview of Study

We conducted a study with students from the Koblenz University of Applied Sciences, RheinAhrCampus. Surveys were given out to over 200 students. To obtain comparable datasets with the other European contributions to this publication, only responses from undergraduates in the Business & Social Sciences faculty were included in data analysis. The final dataset comprised 181 students.

In this study, two research models were tested (Figs. 1 and 2). The first model examines CSR education as an antecedent and tests its relationships to the economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic layer of CSR perception as outcomes, i.e. the impact of CSR education in influencing students’ perception and understanding of CSR in businesses. This research model is important for providing preliminary answers to the relevance of CSR education. Does CSR or corporate citizenship garner the support of the society in Germany? More importantly, does CSR education help students understand the parameters of social responsibility in businesses? Testing the relationships between CSR education and the four layers of CSR perception examines the effectiveness of education in broadening students’ grasp of CSR and heightening their awareness to these issues.

The second research model examines the impact of CSR education in the university both on students’ private consumption attitudes and on their attitude as prospective employees. This research model addresses the research question with regard to the impact of CSR education to students’ private attitudes. This transfer of knowledge from the theory learned in the classroom to the practice of individuals’ consumer choices in their private lives tests the efficacy of CSR education outside the realms of academia. Previous research has looked at the way social responsibility is being taught in universities, but few studies have examined the direct and indirect impacts of such education on students (Matten & Moon, 2004).

4.2 Sample and Measures for Quantitative Study

In this study, 133 undergraduate students in their first year, 35 in their second, 8 in their third, and 5 in their fourth years filled in questionnaires. The mean age was 21.73 years old (SD = 3.16), and 55 % of the participants were female. Pen-and-paper surveys were distributed and responses were later entered into a dataset. No names or other identifiers were collected. The survey was completely anonymous and participants were also reminded to respond to the items honestly.

Majority of the participants (73.5 %) was studying in their first year of their undergraduate programmes. The reason the percentage is high is because we targeted students who were having their courses in English so that they were better able to understand the survey. In this university, most of the courses in English are taken in the first year of studies. Admittedly, this poses as a limitation for our study, and this should be considered when drawing conclusions from the results of this study. Participants were asked to respond to items that measured social responsibility education in the university, as well as items on the different layers of CSR perception, consumer attitudes, and prospective employee attitudes.

4.3 Results and Discussion

Data were analyzed using cross-tab analyses. Table 3 represents the frequency tables, and Table 4 shows the means and standard deviations of the continuous variables. The results of the cross-tab analyses are found in Tables 5 and 6. Cells that are highlighted in green show results that are statistically significant at the p = 0.05 level, while cells that are highlighted in yellow represent results that are marginally significant (i.e. the p-value is less than 0.10).

The results for the first research model suggest that CSR education impacted students’ perceptions of CSR in different ways. CSR education did not impact students’ perception of the philanthropical layer of CSR. Perhaps, because the state of CSR in Germany is not as advanced, as mentioned earlier, philanthropy is perceived as something that is remote or distant to a company’s objectives. Therefore, students had a higher awareness with regards to the other layers of CSR perception.

Participants who learned CSR through different teaching methods (e.g., case studies) tended to be more aware about the economic, legal, and ethical layers of CSR perception. It is possible that it is through various teaching methods that CSR education is most effective for students in this university. This is because the study was conducted in a university of applied sciences, with great emphasis on the practicality of concepts, as well as focus on real-life settings. Using different teaching methods, such as case studies, for example, is thus one of the more impactful ways of communicating CSR concepts to students. CSR education was also effective when CSR was learnt embedded in other modules, and when CSR was taught with diverse focus of topics and content. Again, by integrating different concepts and highlighting real-life business settings to students, students were better able to grasp theories related to CSR.

In line with connecting studies with real-life scenarios, participants who learned about CSR during their internships also presented higher awareness about the legal layer of CSR perception. With hands-on learning and experience, students were able to comprehend concepts related to CSR which may not be as effectively communicated through the classroom.

In testing the second research model, we were interested to see if CSR education would impact students’ attitudes in their private lives. Higher consumer support for CSR to internal and external stakeholders was observed when students learned CSR through different teaching methods. Those who attended other CSR activities, such as seminars, conferences, and workshops, showed higher consumer support for internal stakeholders, whereas those who learned CSR with a diverse focus of content showed higher consumer support for external stakeholders (marginally). This highlights the efficacy of applying knowledge in practical contexts in affecting students’ attitudes towards CSR.

According to the results of this study, it was less important that students took CSR courses (either obligatory or elective courses), but rather, what impacted their understandings and attitudes is the way in which CSR is taught. Drawing parallels from theories conveyed in classrooms to real-life business settings through role plays, simulations, case studies, and workshops, strengthened students’ CSR attitudes through connections that they found relevant to their own lives.

Surprisingly, CSR education through internships did not affect students’ attitudes as prospective employees. Instead, it appears that whether or not students took courses related to CSR affected how they imagined their future employers to be. The awareness that corporations indeed have responsibilities to multiple stakeholders could have influenced students to pursue jobs with more socially responsible companies. Yet, CSR education generally did not affect organizational attractiveness and job pursuit intentions for socially responsible firms. These firms were attractive to participants, but CSR education did not affect this relationship. Possibly, this is because social responsibility in companies in Germany has become to be more of an expectation than a factor that makes organizations stand out from their competitors. A more detailed explanation of this is in the following paragraph.

Respondents seemed to have an instinctive understanding of the different layers of CSR, as the scores for these scales were generally high (means of at least 3.67 out of 5). They also generally showed more positive attitudes towards companies which engage in socially responsible practices (mean = 3.94, SD = 0.62), and expressed greater interest to pursue jobs in such organizations (mean = 3.36, SD = 0.62). This is possibly due to the long-standing culture of CSR being implicitly practiced in organizations (without formally acknowledging it as a business strategy) (Antal et al., 2009). Employee well-being generally receives priority in German companies. Employers paying for employees’ social insurance (retirement and unemployment) is just one example of how companies carry out social responsibility. This practice was legislated many years ago and is enforced by the German government, resulting in a paternalistic tradition that tends to be taken for granted and perceived as normal. Thus, students expect their potential employers to be socially responsible.

There is also an overarching work culture that emphasizes work-life balance, where German employees are entitled by law to more holiday leave than in other countries (Passport to Trade, 2014). While the European Union only prescribes a statutory minimum employment leave of 20 days, most Germans enjoy over 30 days of holidays (paid work days) plus six to eight paid public holidays, depending on the region. Weekends are also traditionally protected from work-related issues. Indeed, people in Germany work 1397 hours a year—considerably less than the OECD average of 1765 hours—and Germany ranks among the top ten countries in the Better Life Index (OECD, 2014). The government also rolls out regulations that support family-friendly work practices (Stolz, 2012). However, the impulses for the implementation of a healthy work-life balance are generally expected to come from the government rather than from individual employers.

There is some good news in the results of our study. It appears that students in Germany tend to have a good instinct when it comes to private CSR attitudes without specifically needing CSR education to explicitly explain social responsibility. Although CSR education is deemed not to be absolutely necessary in some cases, an increase in the salience and quality of CSR education could have far-reaching impacts in the future of these students. Incorporating CSR concepts in private decisions may not translate into engagement in similar cognitive processes when one is deciding on business strategies. Improving the state of CSR education in universities in Germany at the present moment might result in companies moving towards more advanced approaches to CSR in the future.

5 Conclusion

There is an increasing demand from various stakeholders to improve the situation of CSR and CSR education in Germany. As soon as a company is reputed to make an exceptional annual profit, the general opinion is that this company should “give back” to society. German companies and universities are making progressive steps in embedding CSR in their official statements and objectives in an attempt to keep up with this demand. The German government also continues to roll out initiatives to encourage CSR.

However, in this information-rich era, it is not enough to simply express interest in CSR. Consumers consciously make more informed and moral decisions, and unethical business practices are more easily discovered through regular audits, informal investigations and the media. Companies and educational institutions in Germany need to be proactive and integrate CSR into their core strategies and core curricula respectively, and ensure the successful implementation of socially responsible behaviors and activities. Business schools could do more to strive for a fully integrated approach that involves stand-alone CSR courses, delivering basic theoretical input combined with practical case studies to develop students’ abilities in dealing with and resolving ethical dilemmas.

While the conclusions from our study have limitations, it appears that students in Germany seem to have a clear idea with regard to the levels of CSR they personally expect from companies. They expect the products they purchase to be produced in an ethical way, and show preference towards socially responsible companies when it comes to potential employment. These private attitudes, however, do not seem to correlate with formal education in CSR at the university level. Instead, they may stem from their general culture and upbringing. While German students seem to be naturally aware of CSR issues, formal teaching of CSR in classrooms could further refine these instinctive judgments to be developed into rational, deliberate business decisions. For this, the pedagogical perspective needs to shift from a teacher-centric to a learner-centric form of experiential learning, with faculty members encouraging an atmosphere of perspective-taking. CSR ambassadors in universities can also foster ethical thinking at a young age by leading the integration of CSR both in coursework and collaborations with the community.

References

Antal, A. B., Oppen, M., & Sobczak, A. (2009). (Re)discovering the social responsibility of business in Germany. Journal of Business Ethics, 89, 285–301.

Borgmann, L. (2009). Exploring Web 2.0 and mentoring as tools for lifelong learning. In H. Keegan & A. Fox (Eds.), Mentoring for 21st century skills (pp. 59–80). London: University of Salford.

Borgmann, L., & Kokareva, N. (2014). Sustainability of CSR projects in times of economic crises. In D. Türker, H. Toker, & C. Altuntas (Eds.), Contemporary issues in corporate social responsibility (pp. 105–124). Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Buchholtz, A. K., & Carroll, A. B. (2008). Business and society (7th ed.). Stamford, CT: South-Western Cengage Learning.

Cornelius, N., Wallace, J., & Tassabehji, R. (2007). An analysis of corporate social responsibility, corporate identity and ethics teaching in business schools. Journal of Business Ethics, 76, 117–135.

Davis, J. H., Ruhe, J. A., Lee, M., & Rajadhyaksha, U. (2007). Mission possible: Do school mission statements work? Journal of Business Ethics, 70, 99–110.

Deloitte. (2009). Corporate social responsibility: Verankert in der Wertschöpfungskette [Anchored in the value chain]. www.deloitte.com/assets/Dcom-Germany/Local%20Assets/Documents/de_CB_CSR_R_80409.pdf

Desplaces, D. E., Melchar, D. E., Beauvais, L. L., & Bosco, S. M. (2007). The impact of business education on moral judgment competence: An empirical study. Journal of Business Ethics, 74, 73–87.

Giacalone, R. A., & Thompson, K. R. (2006). Business ethics and social responsibility education: Shifting the worldview. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 5, 266–277.

Gruber, V., & Schlegelmilch, B. B. (2013). Integration and exchange: How executive MBA students envision ethics education. Journal of Marketing Education. doi:10.1177/0273475313490169.

Kraus, P., & Britzelmaier, B. (2012). Corporate sustainability management: Evidence from Germany. Journal of Global Responsibility, 3, 248–262.

Kröher, M. O. R. (2005). Good Company Ranking: Tue Gutes und profitiere davon [Good company ranking: Do good deeds and profit from them]. Manager Magazin, 2, 80–96.

Maignan, I. (2001). Consumers’ perception of corporate social responsibilities: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Business Ethics, 30, 57–72.

Matten, D., & Moon, J. (2004). Corporate social responsibility education in Europe. Journal of Business Ethics, 54, 323–337.

McCabe, D. L., Butterfield, K. D., & Trevino, L. K. (2006). Academic dishonesty in graduate business programs: Prevalence, causes, and proposed action. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 5, 294–305.

McCabe, D. L., Trevino, L. K., & Butterfield, K. D. (2002). Honor codes and other contextual influences on academic integrity: A replication and extension to modified honor code settings. Research in Higher Education, 43, 357–378.

Mitchell, T. R. (2007). The academic life: Realistic changes needed for business school students and faculty. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 6, 236–251.

OECD. (2014). OECD Better life index, Germany. http://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/countries/germany/

Passport to Trade. (2014). Work-life balance in Germany. http://businessculture.org/western-europe/business-culture-in-germany/work-life-balance-in-germany/

Piper, T. R., Gentile, M. C., & Parks, S. D. (1993). Can ethics be taught? Boston: Harvard Business Press.

Rasche, A. (2011). The principles for responsible management education (PRME)—a ‘call for action’ for German universities. In M. Haase, S. Mirkovic, & O. J. Schumann (Eds.), Ethics education: Unternehmens- und Wirtschaftsethik in der wirtschaftswissenschaftlichen Ausbildung [Company and business ethics in business education] (pp. 119–136). Munich: Rainer Hampp Verlag.

Rasche, A., Gilbert, D., & Schedel, I. (2012). Cross-disciplinary ethics education in MBA programs: rhetoric or reality? Academy of Management Learning & Education. doi:10.5465/amle. 2011.0016A.

Reifferscheid, G., & Heinzen, M. (2015). Developing tomorrow’s leaders: Role and responsibilities of business schools and ethics educators. Working Paper. Koblenz University of Applied Sciences, RheinAhrCampus

RheinAhrCampus. (2015). Koblenz University of Applied Sciences, RheinAhrCampus. http://www.hs-koblenz.de/rac/index/

Schwerk, A. (2010). Corporate Responsibility in der akademischen Ausbildung von Managern [Corporate responsibility in the academic training of managers]. In F. Theis & S. Klein (Eds.), CSR-Bildung [CSR education] (pp. 112–128). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Sidhu, J. (2003). Mission statements: Is it time to shelve them? European Management Journal, 21, 439–446.

Silberhorn, D., & Warren, R. C. (2007). Defining corporate social responsibility: A view from big companies in Germany and the UK. European Business Review, 19, 352–372.

Stolz, M. L. (2012). Work-life in Germany. Chestnut Hill, MA: The Boston College Center for Work & Family.

Swanson, D. L., & Fisher, D. G. (2008). Advancing business ethics education. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Trevino, L. K., & Nelson, K. A. (2010). Managing business ethics. New York: Wiley.

Zadek, S. (2004, December). The path to corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following research assistants for their invaluable help in this project: Georgia Millroy, Laura McGuire, Dennis Rayuschkin, Yonatan Tewelde, and Franziska Brünker.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rajah, R., Reifferscheid, G., Borgmann, EL. (2016). Social Responsibility Education in Germany. In: Turker, D., Altuntas, C., Idowu, S. (eds) Social Responsibility Education Across Europe. CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26716-6_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-26716-6_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-26714-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-26716-6

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)