Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to (a) explore stakeholder identities of a grassroots cause-related sporting event; and (b) gain a better understanding of how identities are related to stakeholder development, support of the event, and future intentions. We used a mixed methods research design that consisted of two studies: qualitative followed by quantitative. Study 1 explored stakeholder identities and how they are related to stakeholder development and support of the event, and Study 2 examined how future intentions regarding attendance, donations, and sponsor support differ based on levels of stakeholder identity. Sports marketing and non-profit management literature streams as well as identity theory and social capital theory informed our studies. The National Kidney Foundation Surf Festival was selected because it is a grassroots cause-related sporting event with financial success over the last two decades. In addition, a surf contest, an action sport, is a unique sport setting in the nonprofit sector, which offers insight to marketers seeking to target subcultures. The findings of the qualitative study revealed three identities relevant to participants: sport subculture, community, and cause. A framework emerged from the data that illustrated how these identities unite together to generate social capital, which is linked to effective volunteer and sponsorship management. Quantitative analysis through survey data provided further evidence of the impact of identification with a cause-related sport activity on consumer outcomes. Results indicated attendees with high surf-related identity are more likely to attend future Surf Festivals, have higher intentions to donate to the cause, and have higher sponsor purchase intentions compared to those with low self-identity with the sport subculture. The conclusion discusses implications, framing the findings through the intersection of the sports marketing and non-profit sector industries, and provides suggestions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Competition and not-for-profit organizations (NPOs) are two phrases that are rarely associated; however, the NPO sector has grown 25 % in the last decade positioning it as the third largest industry in the U.S. and contributing to 5.5 % of the gross national product (GDP) (Blackwood et al. 2012). The limited funds available from individual donors, the government, corporations, and foundations have resulted in increased interest in marketing by the NPO sector (Blery et al. 2010; Pope et al. 2009). “Given the multifaceted ability of sport to contribute to health, engage a diverse audience, and promote social inclusion” (Sherry 2010, p. 61), hosting cause-related sporting events has become a popular marketing strategy used by NPOs to break through the promotional clutter and gain a competitive advantage (Higgins and Lauzon 2003). A cause-related sporting event has the ability to bring disparate groups together (Deloitte 2010), which helps an NPO expand its’ reach to different target audiences. These events allow participants and consumers to be involved in a sport they enjoy while simultaneously serving a cause (Scott and Solomon 2003; Wood et al. 2010). As a result, NPOs are hosting a range of traditional sporting events such as walks, runs, bicycle rides, and golf. For instance, the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) is one of numerous NPOs that utilizes physical activity events to raise funds and awareness to support the organization’s mission.

A more recent strategy used to stand out from the crowded calendar of 5 K races and expand the participant base is to host an action sports event (i.e., wakeboarding, motocross, BMX freestyle, surfing, windsurfing, skateboarding, snowboarding, and freestyle skiing). Miloch and Lambrecht (2006) define grassroots and niche sports as non-mainstream sports in which the participants and supporters represent a sub-segment of consumers. Action sports are unique, grassroots sports as often they are integrally linked to a community, which offers the ‘ideal’ space for the sport. For instance, Orlando, Florida is known as ‘the’ professional training destination for wakeboarding (Parris et al. 2014). Another example is the relationship between Cocoa Beach, Florida and surfing, which is known as the “surfing capital of the East Coast” (CocoaBeach.com 2014). It is the home town of the most successful surfers of all time—Kelly Slater, eleven-time ASP World Tour Champion—and where every Labor Day the NKF of Florida hosts the largest charity surfing competition in the world. Previous research has explored mega-sporting events’ impact on country image (Florek et al. 2008; Gibson et al. 2008; Green et al. 2003; Nebenzahl and Jaffe 1991; Wonjun and Chang 2009); however, up until now there remains little discourse about sport marketing as positioned within the NPO and public sectors. In addition, the action sports industry is largely untapped by the NPO sector and an unexplored research area. Offering an action sports cause-related event could help NPOs extend their reach to the community and the sport subculture embraced by a specific action sport.

Unlike traditional advertising that mainly utilizes indirect communication tools, a grassroots sporting event creates a medium for producers and consumers to have direct interaction. The close interaction inherent in a grassroots sporting event allows the host organization to become involved in activities of its target consumer, create brand awareness, and build community support. This direct interaction between consumers and producers enhances the ability for marketers to gain the consumers’ attention (Cornwell 2008). Participation in grassroots and niche sports (i.e., action sports) has continued to grow, while the growth of team sports has declined (Beal and Wilson 2004). As these sports grow in popularity both the sport itself and the consumer evolve over time (Parris 2013). This can be seen in the changing demographics of NASCAR fan culture, which used to be mainly southern white men but has expanded to include different regions of the country, women, diverse ethnic groups, as well as higher income and educated consumers (Amato et al. 2005). As sports marketers and NPOs begin to use grassroots sporting events as a medium to deliver their organization’s message (Miloch and Lambrecht 2006), it is imperative they conduct market research to understand the expanded target audience of action sport consumers. However, despite the popularity of these events, there has been limited discourse regarding who are the target consumers of grassroots cause-related sporting events.

Thus, the aim of this study was to (a) explore stakeholder identities of a grassroots cause-related sporting event; and (b) gain an understanding of how identities are related to stakeholder development, support of the event, and future intentions. Sports marketing and non-profit management literature streams, as well as identity theory (Stryker 1968; Stryker 1980; Stryker and Burke 2000) and social capital theory (Coleman 1988; Putnam 1995) informed this investigation. The National Kidney Foundation Surf Festival was selected because it is a grassroots cause-related sporting event with financial success over the last two decades. The event raises over $150,000 per year compared to the average cause-related sporting event that raises only $3000 (Higgins and Lauzon 2003; NKF 2010; Parris and Welty Peachey 2012). In addition, a surf contest is a unique sport setting, an action sport in the nonprofit sector, which offers insight into the construction of identities and their relationship to development and support. We used a mixed methods research design that consisted of two studies. Study 1 qualitatively explored stakeholder identities and how they are related to stakeholder development and support of the event, and Study 2 quantitatively examined how future intentions regarding attendance, donations, and sponsor support differ based on levels of stakeholder identity. This research illustrates how NPOs can extend their reach to create a larger community of stakeholders and generate social capital by bringing together a community, a sport subculture, and a cause.

2 Literature review and theoretical frameworks

To understand stakeholder identities of a grassroots cause-related sporting event, and to explore how stakeholder identities are related to stakeholder development and support of the event. Our work is aligned with Frisby and Millar’s (2002) call for research in sport to explore both individual and community benefits. Taken together, these lenses can help illuminate the value of stakeholder identities and subcultures as effective marketing tools for sport marketers and NPOs.

2.1 Event marketing as a competitive edge for NPOs

One of the main differences between NPOs and the private sector is that financial resources do not come “directly from those who receive the benefits which the organization produces” (Lewis 1998, p. 436). This represents a significant challenge for NPOs; how to create a marketing plan that satisfies management objectives for generating support from stakeholders other than their immediate constituents (Taylor and Shanka 2008). Many causes supported by NPOs, such as kidney disease, are intangible to those who are not afflicted with the condition. In order to generate revenue, NPO marketers need to form an emotional connection with organizations and individuals other than those closest to it. Research has shown that “event marketing, in conjunction with consumers who are enthusiastic, active, and knowledgeable about the sponsor and event, serves as a valuable lever to engage the consumer” (Close et al. 2006, p. 420). A cause-related grassroots sporting event as a focal point has the ability to bring disparate groups together to rally around the cause and serve as a catalyst for positive change.

Historically, companies have hosted events as a component of their marketing strategy. In the last three decades, hosting events has become an increasingly popular medium for the public and private sectors to reach their target audiences (Higgins and Lauzon 2003; Taylor and Shanka 2008). New events are added every year to address consumers’ growing desire to participate events, which align with their lifestyles (International Event Group IEG 2014). Corporations are looking to increasingly utilize sport sponsorships in order to meet consumers’ changing habits and target specific lifestyle segments (McGlone and Martin 2006).

2.2 Lifestyle marketing: targeting actions sports’ consumer identities

Grassroots cause-related sporting events are a marketing tool used by NPOs to extend their target audience to sport consumers, and to provide opportunity for these consumers to engage in their lifestyle by associating with the sport. According to Hanan (1980), lifestyle marketing (LM) captures the target market by creating an association between the company’s brand or cause by tailoring the marketing message to match the consumers’ lifestyle, interests, and opinions (psychographics), and their recurrent patterns of behavior. Sponsorships and events create a non-intrusive two-way dialogue that connects the consumer in an environment that synergistically fits with the consumer’s lifestyle (IEG 2014; Miloch and Lambrecht 2006). According to the International Event Group (IEG), corporate sponsorship is the fastest growing marketing trend in the U.S. It has grown from $850 million in 1985 to $19.8 billion in 2013. Of the $19.8 billion, spending on sports represented $13.68, with $1.78 billion spent on causes and $839 million on events (IEG 2014). Research has demonstrated that cause-related marketing can enhance a company’s image, satisfaction, and loyalty, increase sales, and increase consumers’ willingness to pay (WTP) more for a product by giving the cause-corporation association a moral dimension (Galan-Ladero et al. 2013; Irwin et al. 2003; Smith and Higgins 2000).

A fundamental principle that bridges marketing and psychology is that consumers’ lifestyles are linked to their identities, which reflects their consumption of products and brands (Forehand et al. 2002; Stayman and Deshpande 1989). For instance, action sports represent a counterculture lifestyle that embodies “the image of ‘cool’ by encouraging innovation, freedom, rebellion, self-expression, and breaking of established norms” (Parris 2013, p. 142). Research illustrates consumers’ enjoyment of a sporting event is related to their identification with the sport’s subculture (Green 2008). A cause-related sporting event is a unique setting in that it includes two meaningful identities, a cause identity and a sport identity.

2.3 Identity theory

Identity theory is focused on the concept that individuals develop identities through social experiences and relationships (Stryker 1968; Stryker 1980; Stryker and Burke 2000). Callero (1985) examines this relationship in terms of role-identity salience, where certain role identities are prioritized in a hierarchy over others. This hierarchy of role-identities can have an influence on how individuals evaluate themselves and their attitudes and behaviors related to the social worlds in which they interact. Callero (1985) separates role-identities into self-and social-identity, which are two distinct constructs of identification. Identification involves a relationship between “the self” and how an individual is perceived by others (Stryker 1968; Stryker 1980). Self-identity refers to internal definitions of self, based on involvement in an activity. Social-identity refers to perceptions of external evaluation developed through participation in an activity.

Distinct self and social-identity constructs have been examined within the sport context to define sport participants in terms of self-evaluation and to examine the influence of identity on consumer behavior. Nettleton and Hardey (2006) suggested a typology along two continuums: an orientation to running and an orientation to charitable giving. Similarly, Filo et al. (2009) suggested considering the relationship between runners’ recreation-based motives and their attachment to the charity sporting event. Wood et al. (2010) divided charity cycling event participants into segments based on their identity with fundraising for a cause and/or their identity with the sport. In order for NPO marketers as well as sponsors of the event to target market event participants it is vital for them to understand the mixture of subgroups in attendance, which our study examines.

2.4 Social capital theory

Aligned with identity theory, social capital is created and rooted in the inherit characteristics and values of social life. Putnam (1995) defined social capital as the “features of social organization such as networks, norms, and social trust that can facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit” (p. 66). It is assumed that “participation in an activity which involves similar levels of participation from other individuals and which has stated aims and outcomes leads to the accrual of social capital for the participants” (Spaaij 2009, p.249). Over time, participants (i.e., stakeholders) establish formal and informal social networks that foster development of norms of reciprocity and social trust (Kay and Bradbury 2009; Putnam 1995). The formation of trust increases the accrued collective benefits (Nicholson and Hoye 2008). Through the development of social capital both individuals and the wider population benefit from a more supportive, trusting, and effective society (Putnam 1995; Skinner et al. 2008). In the case of a cause-related event, it brings together a complex compilation of social identities, helps to develop relationships across a diverse range of individuals, and facilitates achievement of both personal and shared goals (DeGraaf and Jordan 2003; Parris and Welty Peachey 2013; Portes 2000; Sherry 2010). According to Parris and Welty Peachey (2013), social capital allows stakeholders (participants, organizers, sponsors, host community, a NPO, and supporters) of an event to leverage a much wider range of resources than they could as individual entities.

Although it may be impossible to prove a cause and effect relationship between sport and social change, according to Green (2008), it is possible to examine different sport programs and compare the successful ones to those that are unsuccessful as a way to begin identifying common elements of thriving programs. Scholars have identified three different types of social capital: bonding, bridging, and linking (Coleman 1988; Putnam 1995). The term bonding social capital describes the close ties with family, friends, and individuals within one’s community, such as neighbors (Parris and Welty Peachey 2013; Putnam 1995; Sherry 2010). The concept of bridging social capital refers to individuals and groups that have more distant ties to similar others who share common interests and goals with the NPO or other types of organizations (Burnett 2006; Parris and Welty Peachey 2013; Putnam 1995; Sherry 2010). The final concept is linking social capital, which “delineates those relationships between individuals and groups that cross boundaries, drawn from dissimilar situations” (Sherry 2010, p. 62). It is the linking of social capital that allows organizations to unite dissimilar groups around a cause or event which then creates a larger group that can draw from an even larger pool of resources. The focus on social capital within sport and leisure studies, according to Burnett (2006), is applicable across sport teams, sport development initiatives, community based-clubs, and sport events. The celebratory nature of sporting events has been show to engender a sense of a community between different social groups, build community cohesion, and develop a more inclusive social capital (Chalip 2006; Parris and Welty Peachey 2013; Sherry 2010; Welty Peachey et al. 2013). In summary, we used the sports marketing and non-profit management literature streams, identity theory, and social capital theory to answer the overarching research questions (provided below) and guide data collection and analysis. Next, we provide a brief background of our research setting and an overview of our study.

3 Research context and study overview

The setting for this research was the 2010 25th Annual NKF Surf Festival Pro/AM, held on Labor Day weekend in Cocoa Beach, Florida. The event was a result of the heartfelt commitment of former professional surfer, Rich Salick and his twin brother Phil, who put his life on the line in 1974 by donating a kidney to save Rich’s life. Only 2 years after Rich’s first transplant, the two brothers, excited about the success of the transplant, wanted to better the lives of other kidney patients. Using their life-long knowledge of the surf industry, they created a series of tournaments to raise money and awareness about kidney disease. At the first event the brothers, along with support of their surfing friends and the local community, raised $125 which they put in a brown paper bag and delivered to the local dialysis center. Yearly events continued with the largest amount raised being $1600. Then in 1985, through the encouragement and support of Craig Tisher, Chief of Nephrology and Hypertension at the University of Florida and Region 2 Vice-President of the NKF, the event took on national sponsorship and became the NKF Florida Team Invitational Pro-Am Surfing Tournament, with the first event grossing more than $60,000. Over the years it has become the largest charity surfing competition in the world, and the principal fundraiser for the NKF of Florida, surpassing funds raised in golf tournaments and walks. The event is 4 days long and includes a surfing competition, food and music, a banquet, and a silent auction. The proceeds go to support research, patient programs, education, and organ donation (NKF 2010).

To gain an understanding of stakeholder identities of a grassroots, cause-related sporting event, and of how identities are related to stakeholder development, support of the event, and future intentions we used a sequential, exploratory, mixed-method research design consisted of two studies: qualitative followed by quantitative. Study 1 qualitatively explored the following research questions: (a) What are the identities of core stakeholders of the event (founders, staff, volunteers, sponsors, and competitors)?; and (b) How are their identities related to stakeholder development and support of the event? Study 2 quantitatively explored the following research question: Do future intentions regarding attendance, donations, and sponsor support differ based on levels of stakeholder identity? Data were collected at the 2010 NKF Surf festival through: (a) semi-structured personal interviews (staff, founders, volunteers, sponsors, and competitors); (b) direct observations; and (c) a survey (n = 480) accessing the demographics, future intentions (attendance, donations, sponsor purchases), and self and social-identity of attendees. Data collection for the qualitative study began 5 weeks prior to the event and was completed during the event. The survey was collected during the 3 days of the surfing competition on the beach. Next, we present the methods and findings and discussion for the qualitative study (Study 1) followed by the quantitative study (Study 2).

4 Study 1: qualitative

In study 1 we investigated the identities of core stakeholders of the event (founders, staff, volunteers, sponsors, and competitors), and how their identities were related to stakeholder development and support of the event.

4.1 Methods

4.1.1 Sample and data collection

To collect the data an organizational diagnosis perspective was adopted (Alderfer 1980), which has been successfully used by other studies examining organizations (Cunningham 2009; Ely and Thomas 2001). Alderfer (1980) defined organizational diagnosis as:

A process based on behavioral science theory for publicly entering a human system, collecting valid data about human experiences within that system, and feeding that information back to the system to promote increased understanding of the system by its members (p. 459).

This approach was appropriate because of the NKF of Florida’s request to work collaboratively with the authors to evaluate the event. In concurrence with Alderfer’s (1980) recommendations to conduct a diagnosis of an organization, multiple data sources were utilized. Data were collected through semi-structured personal interviews and direct observations (Lincoln and Guba 1985). Since a successful grassroots cause-related sporting event requires involvement and participation from multiple constituents, the participants included staff, founder and co-founder, volunteers, sponsors, and competitors whose involvement with the event ranged from two to over 25 years. Table 1 provides demographic characteristics for the 18 study participants in the personal interviews.

During the data collection process, purposive sampling was used to ensure that “certain types of individuals or persons displaying certain attributes are included in the study” (Berg 2001, p. 32). Interviews were conducted in a semi-structured format using the guidelines by Lincoln and Guba (1985) and recommendations from Rubin and Rubin (1995). The interview guide was based on research and peer debriefing with NPO executives and academics who have worked in the non-profit sector, and was drawn from identity and social capital theories. Questions were focused on the following topics: motivation for involvement, role(s) in the event, self and social identities related to the sport, community, and cause, the informal and formal relationships built through the participation of the event (i.e., social capital), and the overall effectiveness of marketing and management. Informed consent was obtained prior to each interview, which lasted between 40 and 90 min, was recorded digitally, and then transcribed verbatim. Additionally, field notes were kept in a reflective journal at volunteer meetings prior to the event (n = 4) and during each day of the event, where the first author documented personal observations and perspectives to aid in understanding the complexity of social dynamics and how participants’ personal attitudes and biases can impact the research process (Glense 2006; Maxwell 2005).

4.1.2 Data analysis

To analyze the data (interviews and direct observations), open, axial, and selective coding was used (Creswell 1998; Strauss and Corbin 1990). NVivo9 was used to store and integrate the data. Initially, we used open coding to condense data into preliminary categories. For example, several open codes encompassed: subculture, community, social capital (bonding, bridging, linking, and reciprocity), identity (sport, community, and cause), marketing strategies, stakeholders’ roles, managerial decisional making process, volunteer management, and sponsorship management. Secondly, we organized the open codes into axial codes by grouping related codes together (Neuman 2006). As an example, the open codes of rituals (i.e., eating at Norman’s every Friday), shared experiences (i.e., historical references to informal and formal community events), and values and loyalties (i.e., unique strengths and perspectives of the community) were clustered together to form the axial code of community culture. This process assisted us in discovering categories, which are the themes presented in the findings and discussion section. Lastly, selective coding was utilized to integrate the data to support the emerging conceptual codes (Creswell 1998).

Creswell and Miller (2000) define trustworthiness in a qualitative study as “how accurately the account represents participants’ realities of the social phenomena and is credible to them” (p. 124). To improve dependability and confirmability, the authors not involved in the data collection served as auditors (Lincoln and Guba 1985). A peer review allowed the first author to maintain a ‘scientific state of mind’ by testing conclusions and developing alternative explanations (Locke et al. 2000). In addition, as recommended by Alderfer (1980), the first author conducted member checks with all study participants, where they reviewed the transcripts and study interpretations and provided feedback. Participants generally agreed with study conclusions.

4.2 Findings and discussion

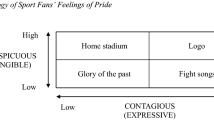

The findings of our qualitative study revealed three self-identities relevant to stakeholders of the NKF Surf Festival: sport subculture, community, and cause (see Table 1). The grassroots cause-related sporting event serves as a catalyst to bring these identities together (Deloitte 2010), which helps foster social capital. A conceptual framework emerged from the data that illustrates how stakeholder identities of a cause-related grassroots sporting event unite together to generate social capital. Figure 1 presents a conceptual framework of how to build social capital by aligning stakeholder identities at a grassroots cause-related sporting event. Because the core reason behind hosting a cause-related grassroots sporting event is the cause itself, the cause is represented in the top circle of the Venn diagram. The two identities that help support the cause are the sport subculture and the community, which are the bottom two circles. At the intersection of these three identities (cause, sport subculture, and community) is the social capital generated by uniting these subgroups together.

The conceptual framework which emerged from the data illustrates how these three identities of a cause-related grassroots sporting event helped to generate social capital. Figure 2 illustrates how the synergy of these relationships in forming social capital is then also linked to the outcomes of engaging volunteers and building sponsor relationships. Later, in Study 2, it is also shown that this intersection also influences future intentions to attend, donate, and support sponsorships by purchasing products.

Next, we discuss the findings from Study 1 that lead to the development of our conceptual framework.

4.2.1 Sport subculture

Many interviewees stated that what the NKF Surf Fest does extremely well is tap into the surfing subculture of Cocoa Beach. One 11-year volunteer stated: “You have your core group, but all they’re going to do is that surfing [referring to NKF Surf Fest], cause that is what they’re into, that’s what their interested in, they’re all avid surfers.” Strong identification with a subculture in the local community has provided the NKF Surf Fest with a multi-generational, committed, volunteer, sponsorship, and participant pool. A staff member for over 5 years commented: “Surfers I think we’ve had some [volunteers] 7 and 8 years old up to people in their 60s.” Surfing attracts: the Boomer Generation (born between 1946 and 1964) who grew up listening to The Beach Boys whose lyrics reflected Southern California youth surf culture; the Generation X (born between 1965 and 1978) who grew up watching over and over again the seminal 1966 surf movie—The Endless Summer; the highly coveted consumer market Generation Y (born between 1979 and 1994), which seeks the individuality and freedom of expression of action sports (Parris 2013); and, the next generational wave of Digital Natives (born mid-1990s to early 2000s) who grew up playing surfing video games like SpongeBob’s Surf & Skate Road Trip. The NKF Surf Fest’s unique ability of accessing the subculture of surfers in the Cocoa Beach area has given the event both a base of volunteers and an identity to area supporters. The multiple generations who are connected to the surf subculture were observed both on and off the water. For instance, the surf line up (i.e., surfers waiting to catch a wave in the water) consisted of surfers ranging in age from less than ten to over 50 years old. On the beach under the shade of 10′ by 10′ canopy tents were groups of college students, families, and clubs. Thus, as a marketing strategy for an NPO targeting a subculture of sport such as an action sport (i.e., surfing), the ability to attract multiple generations is critical for long-term suitability and financial growth.

In working with different sport subcultures it is important that NPOs and sports marketers understand their target audience as each sport will have different social surroundings that shape the values and behaviors of the participants (Mannheim 1936; Mead 1934), especially those highly identified with the sport. Working with a sport subculture can come with its challenges if one is outside of the subculture, as illustrated by the description of a staff member who is not a surfer, on the differences between working with surfers and golfers:

You run a Surf Festival a little differently than a golf tournament. You got different personalities. The golfers drive a Lexus, the surfers drive pick-up trucks. They’ll give you a rude gesture and keep right on going if you don’t work with them properly, and yet they’ll do anything in the world for you . . . and you kind of have to be one of them to get them to do what you want.

An integral part of action sport subcultures is the authenticity of the sport, which defines both what it is and who is part of it, as well as, what it is not and who is not part of the sporting culture (Amato et al. 2005). An authentic core rider is defined by the products worn, used, and consumed (Parris 2013), and by how the rider is perceived by others. Sport subcultures align with identity theory (Stryker 1968; Stryker 1980), in that it is not just one’s self-perception but how an individual is seen by the group that is critical. It is important for the NPO hosting a grassroots sporting event to understand the unique aspects of the sport subculture. Another subgroup integral to a grassroots cause-related event is the local community.

4.2.2 Community

Important to the success of the NKF Surf Fest is what this event represents to the local community. An event volunteer for over 25 years acknowledged the importance of the event to the local community, and the surf culture in the community: “Cocoa Beach is not going to go away as the surfing capital of the east coast. And this is the premier event that establishes us as . . . in that title.” This view is further reinforced by the founder, who said, “we certainly are the biggest [surf] charity event in the world no question about it.” The people involved in this event take pride in its size, its unique status, and the effort it takes to put it on. One volunteer for over 10 years stated:

It’s an exhausting event. It’s always a labor of love. I never feel like it’s not worth every ounce of energy that you have to muster up to do it. I remember . . . I always tell my husband, ‘I feel like I’m walking around on bloody stumps at the end of the night’. But I always feel so good when it’s over. I always feel like it was the most worthwhile thing I did, and you know . . . feels good to have sore feet.

As a result of the 25 years of continuous competitions and the more than 300 volunteers it takes to put on this event, the NKF Surf Fest has woven itself into the cultural fabric of Cocoa Beach. As the first author observed the volunteer tent, it became evident many of the volunteers were on a first-name basis, and already knew the roles they would play at the event based on previous years of volunteering at the Surf Fest. Also, the first author observed that if a new volunteer (first timer) asked to help out, the lead beach coordinator always attempted to pair the “newbie” with a seasoned volunteer, which she believed was important to ensure everyone had fun and would feel a part of the larger event community. The meaning underlying the event, and its importance to the local community, contribute to making it more successful than the average not-for-profit event.

Another factor contributing to the success of the NKF Surf Fest is the event’s consistency. As one volunteer for 25 years said, “what’s good about this event is . . . a lot of people automatically know that it’s going to happen on Labor Day. Labor Day means the NKF Surf Contest. It’s just natural that that is going to happen, everybody expects it to be there.” The consistency of the NKF Surf Fest and its taking claim of the Labor Day weekend is a major competitive advantage. One sponsor for 10 years said, “families look forward to [it] and people in the local community look forward to . . . certain volunteers look forward to . . . it has been something that you . . . could never imagine Labor day without.” The consistency of the event and the choice of a holiday weekend have enabled the NKF Surf Fest to become a trademark event of the Cocoa Beach community.

4.2.3 Commitment to the cause

Of all the questions asked during the 18 interviews the one that every volunteer, staff member, sponsor, and the founder answered identically was why they put on this surfing competition. The reason was best articulated by a volunteer of 25 years “it’s all for raising funds for patient services.” A competitor and a recipient explained the importance of raising funds as “for all those that need kidney transplants or can’t afford all the medical bills and everything.” The NKF of Florida Patient Aid Program provides grocery store gift cards, and money for gas and medication, to those on dialysis or with a transplant. As one volunteer noted, “everyone here knows exactly where the money we raise goes to,” and a sponsor as well as longtime surfer and current board member echoed that “the leadership of the organization has made a strategic commitment to patient services—the organization is proud to say that 83 cents of every dollar raised by the foundation goes directly to patient programs and services”. To ensure the message is clear that this is not just any surfing event, but rather a cause-related surfing event to benefit those touched by kidney disease, there are numerous visual representations at the event ranging from banners and flags, to T-shirts and information booths. In addition, throughout the 3 days of the event, the first author observed the announcer, a surfer and longtime supporter of the event, informing the audience about the cause by inviting donors, recipients, the co-founders, doctors, members of the NKF staff, and community members to tell their stories.

The event also provides a space for transplant recipients as well as those waiting for a transplant, to either learn how to surf for the first time or to help those patients catch their next wave. As one of the first professional athletes to return to competition after a transplant, the founder serves as an example, coach, and cheerleader for those touched by the cause to have fun on the water and to extend their identities from patients to surfers. Surfers touched by the cause, from 3 years old to their late 60s, have caught waves at the festival. Participation in a cause-related supporting event can help develop participants’ self-awareness by expanding their self-identities (Parris and Welty Peachey 2013). The NKF Surf Festival provides the organization the opportunity to let participants know that they are available with a large service offering to provide education on the importance of organ donation, and that it raises funds to support its mission. The clear, constant, and consistent messaging from the leadership of the NKF of Florida regarding the purpose of this event has created a unified volunteer, sponsorship, and participant base committed to the cause.

4.2.4 Social capital – the intersection of three identities: sport, community, and cause

Through the intersection of sport, community, and the cause, social capital development occurred amongst stakeholders (see Fig. 1). The intersection of those who identified with the cause, the community, or the surfing subculture was evident through direct observations conducted at the beach. One example is the mixture of volunteers who help set up the scaffolding towers for the judges, who range from core surfers, individuals touched by the cause, a few identified by all three identities, and a recruited group of students from a local high school. As the event has grown over the years, three different judging towers are needed, and as Phil the co-founder stated, “it takes an army. The community, surfers, and core NKF volunteers all pitch in [he laughs] . . . some you never hear from until they just show up the day of like clockwork every year.” While at times everyone works as a team, at other times throughout the event before, during, and after, individuals fall into roles that align with their identities. For example, many of those dedicated to the cause who do not surf take charge of selling T-shirts and managing ventures; the core surfing crew takes care of the logistics of the ‘surf’ contest; the community comes out to support as spectators, volunteers, and as competitors; and a quick glance at the diversity on the beach shows there are many who share all three identities, two of the identities, one identity, or are just there to have a good time and by being present to learn about the cause. The NPO’s and sport marketer’s role is to give meaning to create a sports landscape, a “third place’ of sociability, which offers a different place other than home and work and can become an “anchor” for community social interaction (Westerbeek and Shilbury 1999).

The NKF Surf Festival is an example of a successful cause-related sporting event that helps to develop three different types of social capital: bonding, bridging, and linking (Coleman 1988; Putnam 1995). The term bonding social capital describes the close ties with family, friends, and individuals within one’s community, such as neighbors (Sherry 2010). All of the interviewees who represented three identities and two identities (n = 12, see Table 1) used the term family, and all interviewees described the group of volunteers as a community. Volunteer meetings occur throughout the year, and become a weekly occurrence several months leading up to the event. However, as highlighted by a longtime volunteer, it is not just the formal meetings for planning the event that help form the bonds, but “the different times we will meet for beer at the surf shop (laughs).” The first author observed while surfing that another informal meeting place for the volunteers, competitors, and organizers of the event was out on the water surfing. The locals know the ‘ideal’ spots to surf, and that is often where you find the Surf Festival crew, which one can often identify by the ‘Salick” stickers on their surf boards or pick-up trucks. These informal and formal social interactions foster development of norms of generalized reciprocity and lead to greater trust (Kay and Bradbury 2009; Putnam 1995). Collective reciprocity extended beyond the event, which was exemplified by five of the interviewees’ stories about how their “Surf Fest Family” came through for them when they needed help. One interviewee spoke about how the Surf Festival family was there for him when was in a coma. While another volunteer told her story:

Originally I got involved because my late husband was a mortgage broker and he heard about Rich wanting to buy a house and no one would give him a mortgage based on the fact he was an organ transplant recipient….my husband helped him get a house and became involved in the Surf Fest….years later my husband became ill Rich was there for us [long pause]…. I still volunteer today.

The concept of bridging social capital refers to individuals and groups that have more distant ties to those who share similar interests and goals with the NPO (Burnett 2006; Putnam 1995; Sherry 2010). In the context of the event, bridging occurs between individuals and groups with distant ties who are involved with the cause and support it. This is exemplified at the NKF Surf Festival through creating links between similar groups that share support for a common cause. These groups include corporate sponsors, host city officials, members of the local community, participants, the local and regional hospitals, and other NPOs supporting transplantation and organ donation. For instance, a staff member highlighted:

After 25 years the relationship has been cemented over time, and these relationships make it easy to roll out the event as everyone from the T-shirt Company, local officials, sponsors, to volunteers just know that this is an event to support.

The Parrot Head Club volunteers as a large group (20 to 40 members depending on the day of the event) every year and over time it has taken ownership of both drink and T-shirt sales. While the Christian Surfers local chapter provides breakfast for early morning volunteers, judges, and competitors, many of their members volunteer and compete at the event. The co-founder, Rich, highlighted “like-clock work they show up every year, sometimes we do not even hear from them until they show up, but we can trust them to be here.” The final concept is linking social capital which “delineates those relationships between individual and groups that cross boundaries, drawn from dissimilar situations” (Sherry 2010, p. 62). In the context of the NKF Surf Fest, linking occurs when individuals and groups not integrally associated with the cause are brought together. An example of bringing distinct groups together is exemplified in the first author’s observations at the silent auction, which is where local restaurants donate food and staff; a regional bank employee manages the money collected; the surf industry as well as local artists and businesses donate items for the auction; and the attendees range from politicians, the transplant community (recipients, donor families, those waiting for an organ transplant, caregivers, and medical professionals), and the surfing industry (competitors both professional and amateur as well as spectators), to members of local community, sponsors, and advocates for the cause. The silent auction is an event itself and allows the NKF to expand its reach to a broader audience as well as provide a time and space to celebrate sponsors and volunteers who help make the event possible.

4.2.5 Engaging volunteers

Volunteer engagement emerged as an outcome linked to social capital development through the intersection of sport, community, and the cause identities of stakeholders (see Fig. 2). Key to the success of any NPO is the engagement and commitment of volunteers. While we discussed the passion volunteers have for this event in the above section, this theme explores the way the event utilizes its volunteers. The NKF Surf Fest represents a huge challenge as it requires more than 300 volunteers over 4 days often working at three different locations simultaneously. In the management of volunteers four factors became apparent through our research: getting volunteers, identifying the individual’s skills, showing the volunteers they are important, and having fun.

For an event requiring hundreds of volunteers over several days one of the most important components is to get enough people involved. The co-founder, Phil Salick, discussed the importance of getting enough people and having them own parts of the event: “The biggest thing is to get as many people involved on your volunteer side to take on bigger tasks, and you want to be able to have people behind you that can readily step right into those shoes and take the operational stuff.” In order to get enough volunteers the NKF Surf Fest relies on a core group of volunteers to form the backbone of the volunteer base as one staff member of 5 years explained: “Most of the volunteers are people that come continuously every year . . . they really take ownership.” The first author observed at three volunteer meetings how core volunteers took lead positions in communities and then stated who from their network they would recruit to form a team. Throughout the meetings when the founders or a committee chair would state we need x or y, then almost every time another individual at the meeting would state “oh, I know someone let me ask if they can help,” or they would volunteer their committee to take on the task. A volunteer of 10 years described it this way: “We sort of put our teams together, the chairman heads, and the teams sort of work most of the requirements . . . you signed up for.”

Having an event that has this level of volunteer involvement and organization requires that the founders find the best way for volunteers to maximize their time and potential. As the founder stated, “you really have to look and learn what the person does, and what their skills are. If we can find that, then we can place them. Or we just ask them, what do you want to do? What would make you happy?” As the CEO of the NKF of Florida phrased it, the founders asking volunteers what their strengths are has, “made it easy for us to roll out everything fairly professionally.” Once volunteers are active in the event the challenge is to acknowledge and make sure each volunteer sees the importance of what she or he does for the event.

Important to the success of the NKF Surf Fest is how it treats volunteers so that they will come back and head committees, and take ownership of the event. The co-founder discussed the importance of volunteer treatment this way:

The biggest thing is the people that we meet and the way we treat them attaches them to the event, and they stick with the event, and if you can do that, and if you have the right people with the right motives, you are going to find a lot of imagination that is going to help the event along.

A volunteer of 10 years said: “We do a good job of treating our volunteers good.” The things the NKF of Florida does to make volunteers feel important to the event are small yet meaningful; volunteers get a T-shirt, there is a volunteer party after the event, and many volunteers discussed the importance of being fed as a way the NKF of Florida shows gratitude toward its volunteers. But all of these little things serve to, as the co-founder noted, attach people to the event.

Likely the most important component in volunteer management seen at the NKF Surf Fest is the role of fun. The co-founder described the original motivation behind the event: “Richard and I kind of hooked this up as a way to have a fun deal years ago.” That same attitude is carried throughout the volunteers, staff, founders, and sponsors of the event. As a volunteer of 18 years said, “You’re on the beach and it’s a beautiful day, and there’s waves, how can you not be happy or be having a good time?” Another volunteer articulated it this way: “You’re literally on the beach having fun . . . I mean how much better can it get?” The fun that the volunteers have is what creates perceptions like this of another longtime volunteer: “I’ve been involved with it so long, it’s such an amazing event, and it’s also so much fun, too.” The fun and multigenerational aspect not only attract volunteers but also sponsors to the event.

4.2.6 Building sponsor relationships

As important as the volunteers were to the event many interviewees stated the importance of another group of stakeholders – the sponsors. Another outcome of social capital generated by the interaction of stakeholder identities is building sponsor relationships (see Fig. 2). Sponsorships are pervasive in sport. Perhaps nowhere are sponsorships more important than in the not-for-profit sector where organizations typically rely on them to underwrite expenses and provide the main source of revenue. While academic literature is full of research regarding the role of sponsorships in event management (Guy and Patton 1989; Miloch and Lambrecht 2006; Varadarajan and Menon 1988), what was unique about this event was the way the event leadership managed those sponsors. The role NKF leadership provided regarding sponsorship management was a critical part of the success of the event. One 10- year volunteer said sponsors are “extremely critical because . . . as far as the actual entry fees you’re not going to make a . . . lot of money . . . if you don’t have the sponsors it is very hard to come out on top.” Sponsors play a critical role in the NKF Surf Festival because they provide the items for the silent auction, food for the volunteers, and the money that really makes this event profitable. But sponsorships go beyond helping out financially and providing food. Sponsors make the NKF Surf Fest a credible event as the CEO of the NKF of Florida explained: “They lend credibility to the event. When you see Kashi or Jeep connected with the NKF event . . . it makes you think that this is a high-level professional [event].”

The NKF of Florida creates sponsorship opportunities in a variety of ways. The first, as the CEO described, is through the founders’ connections in the surfing industry: “If you look on a poster there are a thousand sponsors on those. Those are all relationships that Rich has developed over the years.” Richard and Phil Salick both have what sponsors, volunteers, and staff members described as magnetic personalities. Many of the sponsors involved in the event noted that their relationship with the NKF of Florida began with Rich and Phil. Developing those relationships takes a lot of effort as one of the founders described: “Pounding the sand and . . . the pavement, and then you have to do a lot of follow-up.” Once the founders identified firms interested in becoming sponsors, they began to naturally grow that relationship into long-term friendships. The founder (Rich) said “it is just time, take them to lunch, do things they do.” All of the sponsors interviewed spoke of the friendship that they enjoyed with the founders, how their relationship with the founders extended beyond the NKF Surf Festival. One of the sponsors described it this way:

We’re beyond friends. We’re kind of like family. I mean whenever I have a hard time they’re right there for me and vice versa . . . Rich and Phil come down here and we have them . . . spend the night. We’ll make dinners together. It’s relationship.

While some sponsors got involved because of a relationship with the founders, others sought out the event because of their love of surfing, as one sponsor elucidated: “I think being a surfer for a long period of time had a major influence since it’s my sport that I do and love. It was easy to become a part of this.” Lastly, two sponsors pointed at how this event is unique because it attracts multi-generations, which makes it inviting for everyone. One sponsor standing next to his family highlighted that this is “a great family event that really reaches the youth,” and the other sponsor socializing with a group of his employees said “it’s an event that my whole family can participate in. It has really helped us build relationships and improve community culture.”

In summary, Study 1 qualitatively identified the core event stakeholders’ (founders, staff, volunteers, sponsors, and competitors) self-identities consisted of the community, the sport subculture, and the cause (see Table 1). The intersection of identities formed social capital (see Fig. 1), which led to stakeholder development and support of the event by engaging volunteers and building sponsorship relationships (see Fig. 2).

4.3 Limitations

While this research makes a number of contributions, the results may be basis as they are based on the experiences, knowledge, and opinions of the interviewees (Miles and Huberman 1994). Even though the results revealed positive links between stakeholder identities and social capital, engaging volunteers, and building sponsor relationships in the context of a grassroots cause-related sporting event, this does not indicate that these results are generalizable across all nonprofit or sport marketing events. We took the following steps to ensure that study has trustworthiness (Creswell and Miller 2000; Schwandt 2007): establishing credibility by using triangulation and conducting member checks with participants (Janesick 1994); achieving transferability by the first author keeping a reflective journal that provided a contextual narrative of direct observations (Lincoln and Guba 1985), and; improving dependability and conformability by the authors not involved in data collection (i.e., second, third, and fifth author) serving as auditors by reviewing codes, analysis and interpretations (Erlandson et al. 1993).

5 Study 2: quantitative study

As an extension of Study 1, Study 2 explored how stakeholder identities influence future intentions to attend the event, donate to the cause, and purchase sponsors’ products.

5.1 Methods

5.1.1 Participants and procedures

The NKF Surf Festival is an all-day event with surf heat(s) running continuously from 8 am until 5 pm or later during the 3 days of competition. Over the course of the festival, data were randomly collected between 9 am and 4 pm. Survey completion took approximately 5 min and data were collected close to the two main entrances to the beach, and on the beach around each of the three judging towers. Researchers intercepted subjects (volunteers, sponsors, competitors, and spectators) 18 years of age and above requesting their participation in a marketing research survey for the NKF to assess the event. No incentive was given and 480 surveys were collected with nonresponse less than 2 %. The high response rate was most likely due to the survey being endorsed and actively supported by the charity, the highly committed nature of participants to the charity, and because an intercept method was employed.

5.1.2 Measures

The survey instrument used in the current study contained three sections with a total of 15 items. The first section had six items focused on participant identification with surfing as it relates to the NKF Surf Festival. The identification items were adapted from Callero (1985). Three items focused on self (internal) identification and three items focused on social (external) identification. Identification items were measured on 7-point Likert-type scales. Table 2 provides identification items and descriptive statistics. Section two of the survey contained three intention items measuring future attendance, likelihood to donate to NKF and likelihood to support Surf Festival sponsors. All intention items were measured on 5-point Likert type scales. The final section of the survey contained six items identifying general demographic information of respondents. At the time of the study there was not an instrument developed to measure social capital (see Lee et al. 2013); thus, our quantitative study focused on identity only. In addition, due to requirements from the organization the length of the survey instrument was limited to 15 items.

5.1.3 Analyses

Preliminary analyses were conducted on continuous variables to assess normality. All continuous variables used in the examination were found to be normally distributed except for donor intentions. Therefore, a log transformation was conducted on the donor intentions variable to create normally distributed variable. Descriptive analyses were conducted to profile respondents’ demographics. Next, preliminary analyses were conducted on the self- and social-identity scales to provide reliability-related evidence. Finally, to identify the role of identification in respondent future intentions, three two-way ANOVA models were developed to identify differences based on high or low levels of self- and social-identity with surfing as it relates to the NKF Surf Festival. Prior to these examinations preliminary analysis was conducted on the adapted identification scales to assess reliability and validity. Reliability-related evidence was provided for the self- and social-identity scales, with Cronbach’s alpha scores of .84 and .91, respectively. Average variance extracted (AVE) was assessed for validity-related evidence. AVE scores were satisfactory (.892 and .768 for self and social-identity, respectively), providing construct validity-related evidence. For purposes of the ANOVA model, mean self- and social-identification scores were split in half to represent high and low levels of identification.

5.2 Findings and discussion

5.2.1 Demographics

Grassroots sporting events provide a unique setting and opportunity to create a two-way dialog between the NPO and stakeholders around the cause, community, and sport as our results indicate. Out of 480 respondents, 69 % were from the local area, on average they have attended 3.58 Surf Festivals (SD = 5.56), and they are engaged for the entire duration of the event, staying an average of 3.48 days (SD = 1.94). The number of local attendees highlights how grassroots cause-related sporting events are connected to a community and it’s subculture of the sport. As stated previously, Cocoa Beach is known as the East Coast Surf Capital, which is an identity that is embraced by the community. The considerable amount of repeat consumers from the local area enables both the NPO and the sponsors to build a stronger relationship, and association to their brand (i.e., cause or product) over time. Additionally, grassroots sporting events offer marketers the opportunity to interact with multiple generations of consumers at the same time: 56 % of attendees being female, 45 % being under 30 years old, and 55 % over 31 years old (22.4 % age 18–24, 15.2 % age 25–30, 17.5 % age 31–40, 23.1 % age 41–50, 18.8 % age 50+). The event also attracted a diversity of ethnicities (6.7 % Hispanic, 4.2 % Native American, 2.5 % Asian, 1.7 % African American, 3.3 % other), with the majority of respondents being Caucasian (81 %). Another important variable of the NPO and the sponsors is the ability for the consumer to either donate to the cause or purchase a product. Interestingly, the largest family income category was family incomes of $85,000 or more (24.6 %), followed by $40,000–$59,999 (17.1 %). Almost one-third of respondents had some college education (31.5 %), with 18.1 % of respondents indicating an undergraduate degree.

5.2.2 ANOVA models

To examine comparative differences in spectator intentions based on levels of identification with surfing related to the NKF Surf Festival, we conducted three, two-way ANOVA models (see Table 2 for descriptive results on identification measures). The first ANOVA model examined differences in future attendance intentions based on self- and social-identity. Significant differences were found for self-identity (F(1, 461) = 10.52, p = .001, η 2 = .022). Respondents with high surf-related self-identity were more likely to attend future Surf Festivals (M = 4.55, SD = .659) compared to low self-identity (M = 4.16, SD = .837). Social-identity differences were not found to be significant. Additionally, interaction effects between self- and social-identity were not found to be significant.

The second ANOVA model examined differences in donation intentions based on self- and social-identity. Significant differences were found for self-identity (F(1471) = 18.10, p < .001, η 2 = .037). Respondents with high surf-related self-identity were more likely to donate to NKF (M = 4.42, SD = 3.60) compared to low self-identity (M = 3.46, SD = 1.48). Social-identity differences were not found to be significant. Additionally, interaction effects between self- and social-identity were not found to be significant.

The third ANOVA model examined differences in sponsor purchase intentions based on self- and social- identity. Significant differences were found for self-identity (F(1475) = 5.51, p = .019, η 2 = .011). Respondents with high surf-related self-identity were more likely to purchase from sponsors of the Surf Fest in the future (M = 5.08, SD = 1.90) compared to low self-identity (M = 5.73, SD = 1.55). Social-identity differences were not found to be significant. Additionally, interaction effects between self- and social-identity were not found to be significant.

In summary, attendees with high surf-related identity were more likely to attend future festivals, have higher intentions to donate to the cause, and have higher sponsor purchase intentions compared to those with low self-identity with the sport subculture. Findings provided mixed results when compared to previous literature related to participant-focused and cause-related sporting events. The results suggest self-identity with surfing plays a significant role in consumption intentions for respondents, which is consistent with some aspects of Green’s (2008) work regarding identity and participant-focused sport events. However, Green’s (2008) study also found social-identity played a significant role in consumption. Participants with higher self-identity with a sport were more likely to consume “sport focused” activities like training sessions. However, participants with higher social-identity were more likely to attend social events associated with the sporting event. In the current study, social-identity played an insignificant role for all consumption activities. In the case of Surf Fest, self-identity was considerably stronger for this group of participants and levels of self-identity were more extreme. Therefore, internal identification with surfing is driving consumption intentions in a more decisive manner. Previous literature has also shown identification with the sport itself influences donations at cause-related sporting events (Wood et al. 2010). The current study provided consistent findings regarding the relationship between sport identification and consumption.

5.3 Limitations

Study 2 only focused on respondents at one cause-related festival during 1 year. There are a multitude of cause-related sporting events, both traditional and alternative. These findings may not be generalizable to all types of cause-related sporting events. However, the current study provides a foundation in which to extend research on identity within this context. Additionally, identity was the only construct examined quantitatively. Although identity was the focus of this investigation, there are many attitudes that impact consumer behavior, and they may play a role in cause-related sport investigations. Future studies should expand upon identity to explore relationships between a variety of attitudes and behaviors of those associated with cause-related sporting events. Finally, as mentioned previously, social capital was not examined in the quantitative portion of the current study. This research could be extended through the development or adaptation of a social capital measure to be used within the context of cause-related sporting events.

6 General discussion

Despite grassroots sporting events becoming a popular medium for sports marketers and NPOs to have a direct interaction with consumers, there remains limited research on the stakeholders of these events, and the role they play in making the events a success. Thus, the aim of this paper was to gain a deeper understanding of the identities of the stakeholders of a grassroots sporting event, and how identities are related to stakeholder development, support of the event, and future intentions. Study 1identified three self-identities relevant to stakeholders of the NKF Surf Festival: sport subculture, community, and cause (see Table 1), and illustrated how the interaction of these identities formed social capital (Fig. 1). In combining the findings from Study 1 and Study 2, Fig. 2 illustrates how social capital is linked to stakeholder development and support. Social capital, consisting of the three identities, then facilitated stakeholder development and support of the event by engaging volunteers, building relationships with sponsors, and influencing future intentions to attend the event, donate to the cause, and purchase sponsors’ products.

Collectively, our research points to a number of implications. If social capital—formed through the interactions of three stakeholder self-identities: sport subculture, community, and cause— enhances volunteer engagement, sponsorship relationships, and stakeholders’ future intentions as our findings suggests, NPOs and sports marketers should strive to incorporate stakeholder identity when designing events. This investigation illustrates how a sport subculture of actions sports is linked to a community and how this action sport community can be a viable target market for NPOs and sport marketers. Our findings confirm sport identification plays a role in stakeholders’ intentions. While previous studies have shown social-identity played a significant role in stakeholder intentions, our current study found self-identity was a differentiating factor in future attendance, donor intentions, and sponsor purchase intentions. To foster positive outcomes from social capital, NPOs and sport marketers of events should target multiple stakeholder identities (i.e., community, sport subculture, and cause) and create an even platform that facilitates both informal and formal interactions between the different stakeholders.

Several areas for future research emerged from this investigation. First, researchers can explore how a sporting event can be designed to encourage social capital. Second, there is a need to test and refine the conceptual frameworks presented here. Third, the context of the investigation should be extended to traditional cause-related sporting events to see if the same stakeholder identities are relevant. Lastly, in the burgeoning field of entrepreneurial marketing in conjunction with NPO and sport marketing, researchers should further explore effectuation—an entrepreneurial approach (Sarasvathy 2001)—and how stakeholder identities are a means to multiple given ends (i.e., building social capital, engaging stakeholders, influencing future behavior).

In conclusion, this research illustrates how a grassroots sporting event is an effective medium for NPOs and sport marketers to create a connection with consumers and their community by targeting stakeholder identities. From a marketing perspective, our research should extend to other sport subcultures beyond action sports. Strong communities exist in mainstream participatory sports such as running, cycling, triathlons, and golf. Although this study highlights the highly committed subculture that exists in surfing, strong subcultures exist for mainstream sports as well. The importance of building social capital within grassroots events is not limited to specific subcultures of sport participants. Understanding stakeholder identities related to participatory sport activity and an accompanying cause could have wide ranging implications for a multitude of grassroots sporting events of all. For example the population of runners is a valuable target market for both sponsors and charities. Runners are highly educated, affluent, increasing in overall numbers, and have a variety of motives including running for charitable causes (Lamppa 2011). Hence, understanding stakeholder identity and building social capital within this context could lead to tangible results for NPOs. The increase in both runners and running events could yield tremendous marketing and financial benefits for a partnering organization (Agrusa et al. 2007). However, the current study should be replicated with other mainstream sport events to test its generalizability. The event becomes a focal point that brings stakeholders together from the community, sport subculture, and cause to create social capital. In order to achieve the positive effects of social capital such as engaging volunteers, building sponsor relationships, and influencing future intentions, sport markers and NPOs need to mindfully design events. More research is needed to deepen our understanding of these processes across a variety of contexts.

References

Agrusa, J., Tanner, J., Lema, J., Agrusa, W., & Meche, M. (2007). When sporting events compliment tourism: the 32nd Honolulu marathon. Consortium Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11(2), 61–77.

Alderfer, C. P. (1980). The methodology of organizational diagnosis. Professional Psychology, 11, 459–568.

Amato, C., Peters, C., & Shao, A. (2005). An exploratory investigation into NASCAR fan culture. Sports Quarterly, 14, 71–83.

Beal, B., & Wilson, C. (2004). Chicks dig scars”: commercialisation and the transformations of skateboarders’ identities. Understanding lifestyle sports: Consumption, identity and difference. 31–54

Berg, B. L. (2001). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (4th ed.). MA: Allan and Bacon.

Blackwood, A., Roeger, K., and Pettijohn, S. (2012). The nonprofit sector in brief: public charities, giving and volunteering, 2012. The Nonprofit Almanac 2012. Urban Institute Press. Retrieved June 21, 2014, from http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/412674-The-Nonprofit-Sector-in-Brief.pdf.

Blery, E. K., Katseli, E., & Tsara, N. (2010). Marketing for a non-profit organization. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 7(1), 57–68.

Burnett, C. (2006). Building social capital through an ‘active community club’. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 41(3–4), 283–294.

Callero, P. L. (1985). Role-identity salience. Social Psychology Quarterly, 48(3), 203–215.

Chalip, L. (2006). Toward a distinctive sport management discipline. Journal of Sport Management, 20, 1–21.

Close, A. G., Finney, R. Z., Lacey, R., & Sneath, J. (2006). Engaging the consumer through event marketing: linking attendees with the sponsor, community, and brand. Journal of Advertising Research, 46(4), 420–433.

CocoaBeach.com. (2014). At the beach. Retrieved February 1, 2015, from http://www.cocoabeach.com/at-the-beach/.

Coleman, J. (1988). Social capital and the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 95–120.

Cornwell, B. (2008). State of the art and science in sponsorship-linked marketing. Journal of Advertising, 37(3), 41–55.

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among 5 traditions. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Creswell, J. W., & Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Into Practice, 39(3), 124–130.

Cunningham, G. B. (2009). Understanding the diversity-related change process: a field study. Journal of Sport Management, 23, 407–428.

DeGraaf, D., & Jordan, D. (2003). Social capital. Parks & Recreation, December, 21–27.

Deloitte. (2010). A lasting legacy. Retrieved June 21, 2014, from http://www.deloitte.com/assets/DcomSingapore/Local%20Assets/Documents/SYOG/A%20lasting%20legacy_Aug%202010.pdf.

Ely, R. J., & Thomas, D. A. (2001). Cultural diversity work: the effects of diversity perspectives on work group processes and outcomes. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46, 229–273.

Erlandson, D., Harris, E., Skipper, B., & Allen, S. (1993). Doing naturalistic inquiry. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Filo, K., Funk, D. C., & O’Brien, D. (2009). Examining motivation for charity sport event participation: a comparison of recreation-based and charity-based motives. Journal of Leisure Research, 43(4), 491–518.

Florek, M., Breitbarth, T., & Cojejo, F. (2008). Mega event =mega impact? Travelling fans’ experience and perceptions of the 2006 FIFA world cup host nation. Journal of Sport and Tourism, 13(3), 199–219.

Forehand, M. R., Deshpandé, R., & Reed, A., II. (2002). Identity salience and the influence of differential activation of the social self-schema on advertising response. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(6), 1086–1099.

Frisby, W., & Millar, S. (2002). The actualities of doing community development to promote the inclusion of low income populations in local sport and recreation. European Sport Management Quarterly, 2(3), 209–233.

Galan-Ladero, M. M., Galera-Casquet, C., & Wymer, W. (2013). Attitudes towards cause-related marketing: determinants of satisfaction and loyalty. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 10(3), 253–269.

Gibson, H. J., Qi, G. X., & Zhang, J. J. (2008). Destination image and intent to visit China and the 2008 Beijing Olympic games. Journal of Sport Management, 22, 427–450.

Glense, C. (2006). Becoming qualitative researches: An introduction (3rd ed.). New York: Pearson.

Green, B. C. (2008). Sport as an agent of social and personal change. Management of sports development (pp. 129–145). Oxford: Elsevier.

Green, B. C., Costa, C. A., & Fitzgerald, M. (2003). Marketing the host city: analyzing exposure generated by a sport event. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 5(4), 335–353.

Guy, P., & Patton. (1989). The marketing of altruistic causes: understanding why people help. The Journal of Consumer Marketing, 6(1), 19–30.

Hanan, M. (1980). Life-style marketing. How to position products for premium profits. New York: Amacom.

Higgins, J. W., & Lauzon, L. (2003). Finding the funds in fun runs: exploring physical activity events as fundraising tools in the non-profit sector. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 84(4), 363–377.

International Event Group (IEG). (2014). Sponsorship spending growth slows in North America as marketers eye newer media and marketing options. Retrieved June 22, 2014, from http://www.sponsorship.com/iegsr/2014/01/07/Sponsorship Spending-Growth-Slows-In-North-America.aspx.

Irwin, R. L., Lachowetz, T., Cornwell, T. B., & Clark, J. S. (2003). Cause-related sport sponsorship: an assessment of spectator beliefs, attitudes, and behavioral intentions. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 12(3), 131–139.

Janesick, V. (1994). The dance of qualitative research design: Metaphor, methodolatry, and meaning. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Kay, T., & Bradbury, S. (2009). Youth sport volunteering: developing social capital? Sport Education and Society, 14(1), 121–140.

Lamppa, R. (2011). 2011 Marathon, half-marathon and state of the sport reports. Retrieved February 2, 2015 from http://www.runningusa.org/annual-reports.

Lee, S. P., Cornwell, T. B., & Babiak, K. (2013). Developing an instrument to measure the social impact of sport: social capital, collective identities, health literacy, well-being and human capital. Journal of Sport Management, 27(1), 24–42.

Lewis, B. (1998). Not-for-profit marketing. In C. Cooper & C. Argyris (Eds.), The concise Blackwell encyclopedia of management (pp. 435–436). Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. New York: Sage.

Locke, L., Spirduso, W. W., & Silverman, S. J. (2000). Proposals that work (4th ed.). Newbury Park: Sage.

Mannheim, K. (1936). Ideology and Utopia: An introduction to the sociology of knowledge. New York: Harcourt, Brace and World.

Maxwell, J. A. (2005). Qualitative research design. An interactive approach (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

McGlone, C., & Martin, N. (2006). Nike’s corporate interest lives strong: a cause of cause related marketing and leveraging. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 15, 184–189.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self and society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Miloch, K., & Lambrecht, K. (2006). Consumer awareness of sponsorship at grassroots sport events. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 15, 147–154.

National Kidney Foundation (NKF). (2010). NKF of Florida. Retrieved June 24, 2010, from http://www.kidney.org.

Nebenzahl, I. D., & Jaffe, E. D. (1991). The effectiveness of sponsored events in promoting a country’s image. International Journal of Advertising, 10, 223–237.

Nettleton, S., & Hardey, M. (2006). Running away with health: the urban marathon and the construction of ‘charitable bodies.’. Health An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health Illness and Medicine, 10(4), 441–460.

Neuman, W. L. (2006). Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (6th ed.). Boston: Pearson Education.

Nicholson, M., & Hoye, R. (2008). Sport and social capital. Oxford: Elsevier.

Parris, D. L. (2013). Conceptually meeting expectations of generation Y by building personalised-customised hybrid bundles to target action sports consumers. International Journal of Revenue Management, 7(2), 138–154.

Parris, D., & Welty Peachey, J. (2012). Building a legacy of volunteers through servant leadership: a cause‐related sporting event. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 23(2), 259–276.

Parris, D. L., & Welty Peachey, J. (2013). Encouraging servant leadership: a qualitative study of how a cause related sporting event inspires participants to serve. Leadership, 9(4), 486–512.