Abstract

Previous research has shown that marginalized employees can experience incivility at higher rates, suggesting that incivility can take an insidious form of discrimination termed “selective incivility”. A sample of 6706 employees from a public organization completed measures of co-workers and direct supervisor incivility and a measure of psychological distress. In support of the selective incivility theory, our results highlight that employees from racial minorities and those with physical disabilities are more likely to experience incivility in organizations. Our results also indicate that uncivil behaviors from co-workers are the most influential in the relationship between incivility and employees’ level of psychological distress. Our results allow a better understanding of intergroup dynamics that exclude and devaluate marginalized employees. The practical implications for controlling selective incivility are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

#MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter movements have been confrontational for those who believed gender and racial prejudice were a thing of the past. Although explicit behaviors might have decreased significantly (Swim et al., 1995), research in the field emphasizes that the discrimination has not entirely disappeared but instead has become much more implicit, propagating through subtle and insidious behaviors such as incivility (Cortina, 2008). Incivility is of particular concern: lurking under organizational radars, it refers to behaviors that demonstrate disrespect and disregard and exclude and diminish the performance and participation of all employees (Cortina et al., 2017). Incivility in the workplace is presented as being of lower intensity than other forms of mistreatment (e.g., bullying, Hershcovis, 2011), which means that uncivil acts do not necessarily appear to be unusual (Andersson & Pearson, 1999). It also contains an ambiguous intent to harm (i.e., it is not known whether the person committing the incivility wishes to target the other person; Cortina et al., 2017). Previous research has found that members of an organization may experience incivility differently (e.g., women and racial minorities; McCord et al., 2018), demonstrating that employees who present a stigmatized identity are more likely to be targeted by uncivil behaviors, which constitutes an effective discriminatory mechanism for majority group members to maintain status, power and certain privileges over marginalized people and their reference groups (Kabat-Farr et al., 2020).

The selective incivility theory (Cortina, 2008) conceptualizes how this insidious mechanism allows racism, sexism, and other “isms” to persist in our organizations. The selective incivility theory is grounded in the tenets of social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). One of the core tenets of social identity theory is group membership (i.e., “in-group” and “out-group”). Social identity theory suggests that stereotypes might emerge against “out-group” members. Cortina (2008) suggests that selective incivility (i.e., incivility targeted disproportionately towards out-group members) results from this negative categorization and functions to exclude and denigrate employees who are not part of the group. Incivility can act as a manifestation of broader organizational values and culture (Cortina, 2008), which, when experienced at higher rates by employees with stigmatized identities, presents a complex issue to address for leaders (Kabat-Farr & Labelle-Deraspe, 2022).

The present article builds on the work of Cortina (2008) and Cortina and colleagues (2013) to forge new territory in the selective incivility literature by investigating how specific identity characteristics might influence employees’ experience of incivility. To test our model and hypotheses, we collaborated with a large Canadian public organization interested in furthering their understanding of how interpersonal relationships, including incivility, could affect their employees’ well-being. Along the lines of selective incivility theory and research, a recent survey report has highlighted that if discriminant behaviors are still widespread among Canadian employees, it is mainly because these are increasingly taking insidious forms (Zou et al., 2022). Interestingly, the most recent Canadian Public Service Employee Survey (Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, 2020) presents that marginalized employees, including women, people with a disability, and racial minorities, are more inclined to receive discriminant treatment from colleagues and supervisors (Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, 2020). Over 3.6 million Canadians are now working in the public sector, and this number is on the rise (Di Matteo, 2022). These statistics stress the importance of addressing this phenomenon among the public sector workforce.

Although selective incivility researchers have been giving increasing attention to specific identity characteristics (e.g., sex, race, LGBTQ+, among others, Kabat-Farr et al., 2020), other identities have not yet received the same consideration. In this sense, Kabat-Farr, Settles & Cortina encourage researchers to use the selective incivility theory “as a basis for research on biases against less commonly studied marginalized identities, including minority religious identification, immigrant status, transgender identity, disability status, language or accent” (Kabat-Farr et al., p.257). In light of recent results from the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (2020), we believe efforts should be directed toward better understanding the experiences of disabled employees in the Canadian context. According to Statistics Canada, 15% of working-age Canadians now present a disability status (Cloutier et al., 2018). The originality of the present study stems primarily from being the first to focus on the incivility experiences of employees with physical disabilities. This focus on physical disability is mainly explained by the fact that physical, observable, and immutable personal and background characteristics are the ones that play a central role in the initial categorization process of group members (Harrison et al., 1998). Indeed, research generally supports that initial categorizations are greatly influenced by perceptions of similarity or dissimilarity that are based on surface-level demographic information and that these perceptions change in time through social interactions and teamwork where deep-level information can be shared between members (Cortina, 2008; Harrison et al., 1998). Since the Canadian public sector presents one of the country’s highest turnover rates (i.e., higher than 25%, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, 2020), it may be more difficult for members to create the connections needed to obtain such deeper information. Our study also investigates the incivility experiences of women and racial minorities. While these identity characteristics have been greatly investigated in the U.S. context, there is a need to investigate their experiences in the Canadian context as “cultural, national, organizational, occupational histories, norms and values will all likely influence the manifestation of selective incivility in different national contexts” which “may have similar consequences across contexts but how it is expressed may be very different for each” (Kabat-Farr et al., 2020, p.257).

In addition, the present study investigates the impact of selective incivility from multiple sources (i.e., co-workers and direct supervisor). Schilpzand et al. (2016) encourage researchers to capture and differentiate between the diverse sources of incivility. Indeed, incivility researchers have traditionally not distinguished between sources, even though research suggests that the source of mistreatment matters (Hershcovis & Barling, 2010). Although some studies have highlighted the deleterious effects of supervisors-instigated incivility (e.g., Kabat-Farr et al., 2019), a recent meta-analysis showed that co-workers and supervisors’ uncivil behaviors might have similar impacts on employees’ symptoms of psychological distress (i.e., negative affect, emotional exhaustion, stress, and depression, Han et al., 2022). Interestingly, none of the studies included in this meta-analysis have been comparing incivility from co-workers and direct supervisors simultaneously. Our study fills an essential methodological gap in the literature by being among the first to present a model that captures the effect of direct supervisors’ and of co-workers’ incivility on employees simultaneously, allowing us to weigh the impact of each on employees’ psychological distress. Nevertheless, a handful of studies have investigated how the source influences the relationship between selective incivility and one’s symptoms of psychological distress (Kabat-Farr et al., 2020). Indeed, while it has been demonstrated that “generalized” incivility is related to a higher level of psychological distress (Han et al., 2022), less is known about how individuals’ backgrounds and personal characteristics can shape the impacts on related outcomes (Cortina et al., 2017). Since acting against selective incivility requires specific adjustments regarding one’s identity (Kabat-Farr & Labelle-Deraspe, 2022), a better understanding of the impact of the source is needed to act more effectively in organizations and, thus, to send a powerful signal to marginalized employees that their experience is seen and considered, and that the situation will be addressed.

Theory and hypotheses

Incivility and psychological distress

Researchers have shown that experiencing everyday incivility is associated with a decrease in employees’ psychological well-being (for a recent meta-analysis, see Han et al., 2022). Employees who experience high levels of incivility are more likely to exhibit symptoms of depression (Miner et al., 2014), anxiety (e.g., Geldart et al., 2018), and psychological distress (Lim & Lee, 2011). Employees experiencing incivility also report decreased mental, emotional, and social energy, as well as an increased level of negative emotions (Giumetti et al., 2013). Dealing with incivility daily can be stressful and emotionally draining (Cortina & Magley, 2009; Lim & Cortina, 2005). Over time, these disrespectful exchanges make employees feel devalued (Kabat-Farr et al., 2018) and reduce their optimism (Bunk & Magley, 2013).

The sources of incivility

Incivility can come from several sources (e.g., supervisors, co-workers, customers, or suppliers; Schilpzand et al., 2016), all having a different status regarding the victim and a role, tasks, and responsibilities that are specific to the organization. Power inequalities between instigators and victims play a central role in the occurrence of workplace incivility (Cortina et al., 2017). Power can be defined as one person’s influence over others, creating dependence (Hershcovis & Barling, 2010).

Unequal power in the hierarchical structure (formal power) can influence the imbalance between individuals (Hershcovis, 2011). For example, employees targeted by uncivil behavior on the part of their superior might avoid actively defending themselves for fear of reprisals (e.g., being passed over for promotion; Cortina et al., 2017), thereby forcing them to keep quiet and endure this kind of behavior daily (Cortina & Magley, 2009; Hershcovis & Barling, 2010) found that negative behaviors on the part of the supervisor have greater effects on employee attitudes and behaviors than those of co-workers or outsiders. Another study shows that employees who experience incivility from their supervisor evaluate the incident more negatively (Cortina & Magley, 2009). Finally, a recent study by Kabat-Farr and colleagues (2019) shows that being the target of incivility on the part of a supervisor leads to more devastating impacts on the employee.

Unequal power in the informal structure can also impact the relationship (Cortina et al., 2017). Studies show that employees with less social power are at greater risk of experiencing incivility (Cortina et al., 2002). Some colleagues may have significant social power insofar as they can influence the presence and quality of social relations within the group (e.g., inclusion or exclusion of a person from the group) on an ongoing basis (Hershcovis & Barling, 2010). An example would be people taking advantage of their social power to stigmatize their colleagues who present gender, individual or cultural differences, or even deficiencies in terms of work performance (Cortina, 2008). A recent meta-analysis demonstrates that interpersonal mistreatment has an even more detrimental effect on employees when it occurs in the context of social interactions with co-workers who possess more social power than when it arises through formal actions by their supervisor (e.g., withdrawal of a reward, McCord et al., 2018).

Studies examining the source of incivility have only cursorily examined the differences between the sources, especially regarding the psychological distress of employees (Schilpzand et al., 2016). The present study will examine the differential impact of two of the most influential (i.e., daily interactions between individuals; Rosen et al., 2016) incivility sources on employees’ psychological distress to determine which has the most significant influence: co-workers or direct supervisor.

The selective nature of incivility: women and racial minorities at risk

Laws and policies now prohibit all forms of explicit discrimination and impartiality against marginalized groups within North American organizations (e.g., The American Civil Rights Act; The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms). While overt behaviors might have decreased significantly (Kabat-Farr et al., 2020), many researchers point out that the discrimination did not completely disappear. Instead, it has become much more sophisticated, propagating through insidious behaviors that found their roots in disrespect and disregard for others (i.e., modern manifestations of discrimination; Dovidio et al., 2002; Sue et al., 2007). For example, recent research showed that women and racial minorities are at higher risk of receiving uncivil treatment in the workplace compared to their counterparts (for a recent meta-analysis, see McCord et al., 2018).

Cortina (2008) termed this phenomenon selective incivility: insidious acts resulting from a negative categorization that aims to exclude and denigrate employees who do not share the same social identity characteristics as the majority group members. The theory of selective incivility is based on the tenets of the social identity and categorization theories (Tajfel, 1974; Tajfel & Turner, 1979), within which one of the fundamental principles is group membership (i.e., “in-group” and “out-group “). These theories present that discriminatory treatment might emerge against outsiders (Hogg & Turner, 1985).

Whether of an implicit or explicit nature, prejudices and stereotypes formed towards underrepresented groups, in-group favoritism, and social dominance (Sidanius & Pratto, 2001; Hogg & Turner, 1985), could all lead individuals within the majority group to engage in inconspicuous forms of discrimination in the form of incivility and rationalize this behavior as unrelated to group characteristics (Cortina, 2008). Indeed, studies found that even if most people would like to think of themselves as upstanding moral citizens, many still hold stereotypes against women and racial minorities that tend to be negative (e.g., incompetent, unfriendly, Cuddy et al., 2008). These negative biases, in turn, influence social categorization processes (i.e., placing people into social categories based on relevant information such as race and sex, Dovidio et al., 2001) that are likely to result in negative attributions made to these groups, translating into increased negative interpersonal behaviors (Cortina, 2008).

Moreover, the selective incivility theory poses that group members can use these rude and mundane acts in positions of power to exclude and devalue marginalized people (Cortina, 2008). Social dominance theory states that existing social hierarchy systems do advantage men and majority group members (e.g., Caucasian people in North America; Cortina, 2008) when they wish to access power and status (Pratto et al., 2006; Sidanius & Pratto, 2001). Thus, majority groups are motivated to preserve these privileges and therefore engage in negative treatment of minority groups (Cortina, 2008). In support, a significant amount of research has been accumulated demonstrating how dynamics of power (based on gender, race, or hierarchic position, among others) can forge racial minorities and women’s incivility experiences at work and how having less social power creates a higher risk for them of being on the receiving end of incivility (for reviews of existing literature see, Cortina et al., 2017; Kabat-Farr et al., 2020).

In addition, the theory of tokenism (Kanter, 1977) proposes that employees who are tokens in their workgroup (i.e., a minority based on a salient social identity or characteristic) experience heightened visibility, salience, and increased prejudices and stereotyping. As both sex and race are presented among the most salient and visible social stereotyping categories within work organizations (Eagly & Karau, 2002; Gonzalez & DeNisi, 2009), women and racial minorities might be more likely to experience differential treatments, especially when they must navigate in a traditionally male-dominated domain (Heilman & Okimoto, 2007). For example, several studies have shown that women experienced a higher level of incivility in male-dominated professions (e.g., Cortina et al., 2001, 2002, 2013; Miner et al., 2014; Oyet et al., 2019; Richman et al., 1999; Sumpter, 2019). Sex and race are presented as surface-level characteristics, which are overt and biological differences, typically reflected in physical features (Harrison et al., 1998). Such unchangeable, seeable, and measurable characteristics, combined with an increase in visibility due to tokenism, is likely to translate into heightened stereotype activation, exaggerated perceptions of differences between in-groups and out-groups, and motivate influential and majority group members to reassert existing status hierarchies and reinforce group boundaries (Buchanan & Settles, 2019).

By considering these perspectives and following the theory of selective incivility (Cortina, 2008), we offer the following hypotheses that suggest that both racial- and gendered-based patterns of incivility will also emerge in the Canadian context:

- hypothesis

- 1a: Women will be more likely than men to report experiencing uncivil behaviors from co-workers and direct supervisor.

- hypothesis

- 1b: Women will be more likely than men to report experiencing a higher level of psychological distress, and this will be partially explained by the incivility they experience from co-workers and direct supervisor.

- hypothesis

- 2a: Racial minority employees will be more likely than employees not identifying as a racial minority to experience uncivil behaviors from co-workers and direct supervisor.

- hypothesis

- b: Racial minority employees will be more likely than employees not identifying as a racial minority to report experiencing a higher level of psychological distress, and this will be partially explained by the incivility they experience from co-workers and direct supervisor.

An extension of the theory of selective incivility: the situation of physical disability

Faced with significant concerns related to sexism and racism, found in the studies she conducted with several North American organizations, Cortina (2008) initially developed the theory of selective incivility regarding sex and race (Cortina et al., 2013). However, Cortina also acknowledges that similar arguments can be made regarding other identity characteristics (e.g., sexual orientation, age, and disability status), which are at the heart of prejudices and stereotypes in organizations. Thus, the last decade of research on selective incivility has supported the extension of the theory, highlighting the experiences of employees with various stigmatized social identities in different contexts (e.g., age, LGBTQ + community). Surprisingly, no particular attention has been paid to the uncivil experiences of employees with physical disabilities (Kabat-Farr et al., 2020). According to possible extensions of the theory of selective incivility, we consider physical disability-based incivility as uncivil behavior directed disproportionately towards employees with physical disabilities.

Physical disability includes a variety of physical impairments (e.g., hearing, vision, mobility, flexibility, dexterity, pain, and developmental disabilities, among others) that lead to difficulties in functioning (i.e., activity limitations or restrictions on participation; World Health Organization, 2011). Research indicates that multiple factors, including false stereotypes, negative biases, anxiety, and resentment (for a review of the literature, see: Colella & Stone, 2005; Stone & Colella, 1996), influence how employees are discriminated against because of their physical disability. One example of such influence is the perception that employees with physical disabilities negatively influence their colleagues’ performance by increasing their workload (Colella & Stone, 2005). In addition, accommodations granted to employees with physical disabilities can be perceived as a violation of the rules of distributive and/or procedural justice (Colella, 2001). Colleagues may also act paternalistically with employees with physical disabilities (i.e., in the same way they interact with a child; Jones et al., 1984), showing their superior status in the social and organizational hierarchy (Fox & Giles, 1996). Researchers have also found that employees with physical disabilities receive more negative performance reviews from co-workers (Colella et al., 1998) and supervisors (Lyubykh et al., 2020).

The biases surrounding employees with physical disabilities are complex, and their colleagues can internalize both positive and negative views (Colella & Stone, 2005). However, studies point out that negative attitudes toward employees with physical disabilities are more widespread in organizations (Deal, 2007; Jones et al., 2017). Negative attitudes and beliefs about employees with physical disabilities are concerning, given the growing prevalence of these employees in the Canadian workforce (15% of working-age Canadians live with a disability; Cloutier et al., 2018). Since the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, as well as several provincial regulations (e.g., the Ontario Human Rights Code) openly prohibit discrimination against persons with physical disabilities, we believe that negative attitudes towards employees with physical disabilities could manifest themselves in acts of a more subtle nature, such as incivility.

- hypothesis

- 3a: Employees with physical disabilities will be more likely than employees not presenting physical disabilities to experience uncivil behaviors from co-workers and direct supervisor.

- hypothesis

- 3b: Employees with physical disabilities will be more likely than employees not presenting physical disabilities to report experiencing a higher level of psychological distress, and this will be partially explained by the incivility they experience from co-workers and direct supervisor.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Employees from a large Canadian public sector organization were asked to participate in a confidential organizational survey during work hours. This organizational survey was conducted to evaluate employees’ well-being within the organization. Employees completed the survey online, and one of the offices in charge of employee mental health compiled the data anonymously. The organization shared the anonymized survey data with the second author. In total, 6706 employees and managers completed a self-report measure of workplace incivility as well as a measure of psychological distress. Of this sample, 2241 were men (33.4%), 4075 were women (60.8%), 12 chose “other gender” (0.2%) and 378 (5.6%) did not wish to reply. Of these, 4858 (71%) were employees, 1642 supervisors (24%), and 206 did not wish to answer (5%). As for the other sociodemographic questions, 414 women and 249 men (9.9%) indicated that they were a part of a racial minority group, and 162 women and 98 men (3.9%) reported presenting a physical disability. For job tenure, 26% of respondents indicated being in the organization for less than one year, 29% from 1 to 3 years, 36% for more than three years, and 9% did not wish to answer. Age varied from 18 to 65 years old (mean = 43.95).

Measures

Demographics

Participants self-reported their sex, which we coded as 1 (male) or 2 (female). If they identified as part of a racial minority group, we coded 0 (not identifying as a racial minority) or 1 (identifying as a racial minority), and if they reported presenting a physical disability, we coded 0 (not presenting a physical disability) or 1 (presenting a physical disability).

Workplace incivility

To measure workplace incivility, we used the items from the interpersonal justice and incivility subscale of the Justice Measure (Colquitt, 2001): 1- “Treat you in a polite manner” (reversed); 2- “Treat you with dignity and respect” (items two and three combined from the original survey; reversed); “Make inappropriate remarks or comments.“ The organization selected this scale for its perfect fit with its definition of incivility in the workplace. Indeed, context is essential to recognize and interpret the different forms of mistreatment (Hershcovis et al., 2020). Furthermore, incivility is positively related to perceptions of injustice (Cortina et al., 2017), making this subscale suitable to measure the concept. Participants were first asked, “Please indicate the extent to which your co-workers” then participants were asked the same questions but for their “immediate supervisor”. A Likert-type scale was used with the following answer options: 1- To a very small extent; 2- To a small extent; 3- Somewhat; 4- To a large extent; 5- To a very large extent. A total score was calculated by adding responses to the three questions for their co-workers and the three questions for their direct supervisor. The Cronbach alpha for co-workers and supervisor incivility respectively were: 0.72 and 0.75 the Mean Inter-Item Correlations were: 0.52 and 0.55.

Psychological distress

To measure employee psychological distress, the organizational survey used three questions from the screening measure of psychological distress developed by Kessler and colleagues (K6; 2002). The measure is based on a 5-point Likert-type scale with the following options: 1- Never, 2- Rarely, 3- Sometimes, 4- Often, and 5- Always. This instrument shows good psychometric properties for screening for psychological distress among the general population (see Furukawa et al., 2003; Kessler et al., 2003). Participants were asked to answer the following questions regarding their experience at work in the last four weeks: “Feel so depressed that nothing could cheer you up? “; “Feel that everything was an effort? " and “Feel worthless?“. The Cronbach alpha for the three items used in our sample was 0.86, and the Mean Inter-Item Correlation was 0.68.

Analytic strategies

For the parallel mediation model with two mediating variables, Hayes’ PROCESS macro using a bootstrapping method with corrected confidence estimates was used (MacKinnon et al., 2004; Preacher & Hayes, 2004). In the present study, the 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect was obtained with a bootstrap sampling of 5000 (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

Results

Preliminary analyses

Intercorrelations

Correlations were calculated between measures of incivility by co-workers, incivility perpetrated by direct supervisor, and the measure of psychological distress. Table 1 provides the correlations among the study variables. Results from the correlations showed that incivility from co-workers (b = 0.35, p < .01) and direct supervisor (b = 0.31, p < .01) are associated with increased employee psychological distress. Results also showed that being a racial minority is associated with more incivility from co-workers (b = 0.05, p < .01) and direct supervisor (b = 0.05, p < .01) and that living with a physical disability (b = 0.07, p < .01) or being a woman (b = 0.03, p < .05) is related to increased psychological distress for employees. Furthermore, there is a strong positive association between reports of co-workers’ incivility and reports of supervisor incivility (b = 0.51, p < .05), confirming the idea that incivility may be a part of the organizational culture.

Harman’s single-factor test

To test for common method variance (CMV; Podsakoff et al., 2003), we proceeded to conduct Harman’s Single-Factor test. A Harman one-factor analysis is a post hoc statistical procedure to scan whether a single factor is accountable for variance in the data (Chang et al., 2010). While this method cannot help control or correct the problem of common method variance, it can provide information regarding its absence or presence (Tehseen et al., 2017). The generated output (see Table 2) revealed that the first unrotated factor captured only 36% of the variance in our data. Thus, no single factor emerged, and the first factor did not capture most of the variance (i.e., less than 50%), suggesting that common method variance does not appear to be an issue in the present study. Additional proactive strategies taken by the authors to control for CMV during data collection are discussed in the section below presenting the limits of the present study.

Hypothesis testing

Model 1: gender

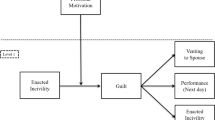

Figure 1 presents the results of a test of the indirect effect of gender on psychological distress through co-workers and direct supervisor incivility. Gender was not significantly associated with co-workers (unstandardized b = − 0.07, p = .23) and direct supervisor (b = − 0.09, p = .027) incivility, not supporting Hypothesis 1a. However, gender (unstandardized b = 0.21, p = .05), co-workers incivility (unstandardized b = 0.43, p = .000), and direct supervisor incivility (unstandardized b = − 0.14, p = .000) were all positively associated with psychological distress. The indirect effect of gender on psychological distress was not mediated by co-workers (b = − 0.03, 95% CI [–0.08, 0.02] and direct supervisor (b = − 0.01, 95% CI [–0.04, 0.01]) incivility, suggesting that there were no significant indirect effects (no support found for gender for Hypothesis 1b).

Model 2: racial minorities

Figure 2 presents the results of a test of the indirect effect of racial minorities on psychological distress through co-workers and direct supervisor incivility. Being of a racial minority group was positively associated with co-workers (unstandardized b = 0.34, p < .001) and direct supervisor (b = 0.37, p = .01) incivility, supporting Hypothesis 2a. Furthermore, co-workers’ incivility (unstandardized b = 0.42, p < .001), and direct supervisor’s incivility (unstandardized b = 0.15, p < .001) were both associated with higher levels of psychological distress, while identifying as a racial minority was not (b = 0.04, p = .76). The indirect effect of identifying as a racial minority on psychological distress was mediated by both co-workers incivility (b = 0.14, 95% CI [0.06, 0.22]) and direct supervisor incivility (b = 0.06, 95% CI [0.02, 0.09]), suggesting that there were indirect effects, supporting Hypothesis 2b.

Model 3: physical disability

Figure 3 presents the results of a test of the indirect effect of physical disability on psychological distress through co-workers and direct supervisor incivility. Physical disability was positively associated with co-workers’ incivility (unstandardized b = 0.28, p < .05) and direct supervisor’s incivility (b = 0.48, p < .01), supporting Hypothesis 3a. Furthermore, having a physical disability (b = 0.93, p < .001), co-workers incivility (b = 0.41, p < .001), and direct supervisor incivility (b = 0.415, p < .001) were all significantly and positively associated with higher levels of psychological distress. The indirect effect of physical disability on psychological distress was mediated by both co-workers incivility (b = 0.12, 95% CI [0.00, 0.24]) and direct supervisor incivility (b = 0.07, 95% CI [0.01, 0.13]), suggesting that there were indirect effects, supporting Hypothesis 3b.

Discussion

The last decades of research have extensively documented the adverse effects that uncivil behavior can cause on employees and organizations (for recent reviews and meta-analyses of the literature, see: Han et al., 2022; Park & Martinez, 2022; Schilpzand et al., 2016; Yao et al., 2022). However, our knowledge is still relatively limited when it comes to understanding the role that employee identities play in their experience of incivility and the associated consequences (Kabat-Farr et al., 2020). Our study is among the first to test a model focusing on selective incivility while also distinguishing the impact of the sources (i.e., co-workers and direct supervisor) of incivility on employees’ psychological distress. Our results show that racial minorities and employees with physical disabilities are particularly at risk of being subjected to uncivil treatment, which significantly impacts their level of psychological distress. The main contribution of our study to the literature on workplace incivility is to be the first to focus on the uncivil experiences of employees with physical disabilities. Moreover, we found that incivility on the part of co-workers appears to have a more significant impact on victims’ level of psychological distress compared to incivility from direct supervisor. Perhaps this might be explained by the fact that employees usually have one direct supervisor and many co-workers; therefore, when employees must navigate a toxic culture or work climate, they have more frequent contact with co-workers than with their supervisor. Collectively, these findings underscore that incivility is not only a way of being, or a lack of interpersonal skills, but that it can take the form of a modern manifestation of discrimination, which can become a hindrance to efforts towards creating a more diverse and inclusive workplace.

Taken together, our results partially support the selective incivility theory (Cortina, 2008). Indeed, we found that employees from racial minorities (H2a) as well as employees with physical disabilities (H3a) are at greater risk of experiencing incivility than Caucasians and non-physically disabled employees, respectively. These findings support the possibility that some disrespectful behaviors might represent a discrete manifestation of racial discrimination as proposed by previous research in organizational (e.g., Cortina et al., 2013) and social psychology. (e.g., Sue et al., 2007). In addition, the present results support the possibility that some disrespectful behaviors represent a discrete form of discrimination based on a person’s physical disability. This finding is consistent with previous research on disability, stating that discrimination against disabled employees is becoming increasingly insidious (Deal, 2007). Our findings concerning physical disabilities contribute to both social and organizational psychology. First, we extend the literature on workplace mistreatment by incorporating issues related to physical disabilities. To date, very few studies have investigated how interpersonal mistreatment might reflect bias against members of marginalized groups (Cortina et al., 2017). A second contribution is to focus on discriminant actions directed at marginalized employees. Indeed, most studies addressing discrimination in social psychology have focused on addressing questions related to cognition and emotion when studying discrimination processes but have mainly neglected actions (Fiske, 2000).

In contrast, our results also showed that women do not receive more uncivil treatment than men (no support for H1a). Although gender is considered to be one of the most visible categories of social stereotypes within organizations (Eagly & Karau, 2002), a recent meta-analysis conducted by McCord and colleagues (2018) shows that the size of the effect of incivility according to gender varies greatly from study to study. Even though the results are statistically significant, it demonstrates that the effect is weak (δ = 0.06; McCord et al., 2018). These disparate results may suggest that incivility does not work consistently against women, highlighting the importance of further research to determine the specific conditions that favor the emergence of uncivil behaviors directed at them (e.g., women who work in a predominantly male environment are more at risk of experiencing forms of gender-based interpersonal mistreatment; Kabat-Farr & Cortina, 2014).

In line with previous research (Han et al., 2022), our results indicate that experiencing incivility at work is positively related to employees’ psychological distress. While our results show that being an employee of racial minority does not necessarily predict a higher general level of psychological distress; experiencing uncivil treatment from co-workers and direct supervisor significantly impacts their level of psychological distress (H2b). For employees with a physical disability, our results also indicate that presenting a physical disability predicts more uncivil behavior on the part of co-workers and direct supervisor and that this dynamic affects their level of psychological distress (H3b). However, although women from our sample presented a higher level of psychological distress than men, the uncivil treatment from co-workers and direct supervisor did not partially explain that relationship (contrary to H1b).

Particularly concerning are the results indicating that employees with physical disabilities have a higher general level of psychological distress, even before being targets of incivility. These findings are consistent with research on physical disability, where it has been found that people with physical disabilities experience as much as three times the number of depressive symptoms compared to the general population (Brown, 2014). Moreover, the relationships in the present study might have been strengthened since our sample included a larger number of women (i.e., 162) than men (i.e., 98). Indeed, research has found that women with physical disabilities are particularly prone to experience symptoms of psychological distress (i.e., estimated to be as much as 13 times more likely to experience clinical-significant levels of depressive symptoms than women among the general population; Hughes et al., 2001; Nosek & Hughes, 2003). These findings are alarming, showing that employees with disabilities might be particularly vulnerable to uncivil behavior and that this might increase their level of psychological distress, which is already higher than that of other employees who do not present a physical disability. Nevertheless, this observation leads us to question the importance of obtaining a more nuanced understanding of the exact nature of the incivility experiences of employees with physical disabilities, as well as examining other factors related to the context that could signal to them that they have no place in the team or the organization.

Finally, by distinguishing the sources of incivility, we found that uncivil behaviors perpetrated by the direct supervisor are less impactful for employees’ psychological distress than the uncivil behaviors coming from co-workers. Our results are consistent with a recent meta-analysis conducted by Dhanani and colleagues (2018), which demonstrates that uncivil behaviors from co-workers exert a more significant influence on the health and well-being of employees. Indeed, when uncivil behaviors are perpetrated by several co-workers simultaneously, and that one’s differences are perceived as being the cause of it, it might reflect symptoms of larger cultural and organizational factors, and diverse members can take that as a cue that they are not respected or valued (Buchanan & Settles, 2019). As a result, organizations can take strategies to act against incivility among their ranks. Some strategies will be discussed in the next section of the present paper.

In sum, the results of our study answer recent calls from experts in the field (Cortina et al., 2017; Kabat-Farr et al., 2020) who raised the need for continued research efforts in connection with the experience of incivility for certain groups of marginalized employees in the workplace. Among other things, the results demonstrate the need to consider the context and its demographics (e.g., group composition) to better understand the experiences of marginalized employees.

Practical implications for organizations

The findings of this study raise clear implications for both individuals and organizations. First, leaders and managers seeking to address workplace incivility should also be aware of its potential role as a modern form of discrimination. In this sense, results show that employees from visible minorities and those with physical disabilities are at greater risk of being the target of uncivil behavior. Although organizations are increasingly adopting policies and practices that seek to increase diversity and inclusion, most have limited their efforts to eliminating explicit forms of discrimination (Hayes et al., 2020). Since little, if any, legal attention is directed to subtle, unobtrusive, and ongoing forms of abuse that aim to diminish, deter, and discriminate against those with a stigmatized identity (Kabat-Farr et al., 2020), it is essential for organizations to develop proactive strategies to effectively address patterns that may emerge against these employees.

Second, the present study shows that, contrary to what is mainly advanced in the literature, uncivil behaviors on the part of co-workers have a more negative impact on victims’ levels of psychological distress. When employees begin to behave in an uncivil way in the workplace, their manager needs to address the problematic behaviors quickly, fairly, and systematically, since such behaviors seem to spread rapidly among members of an organization (Foulk et al., 2016) and result in consequences that are devastating both personally and professionally (Han et al., 2022). Considering that incivility can also take the form of modern discrimination, it is essential to question the strategies that could be adapted according to the identity of the victim. To address these situations, organizations, and practitioners would do well to draw inspiration from what is done in the literature on interpersonal mistreatment such as microaggressions (e.g., Sue et al., 2019). As incivility is a subtle and ambiguous form of interpersonal mistreatment that can sometimes be unintentional or even an implicit manifestation of impartiality towards marginalized employees (Cortina, 2008), all new and current employees should be educated and trained in expected interpersonal behavior.

Third, several researchers have demonstrated the influence that leadership can have on the control or the emergence of incivility between members of an organization. For example, a permissive leadership style makes incivility acceptable to employees, since the behaviors are tolerated in the work environment without being addressed (Baruch & Jenkins, 2007). Along the same lines, a passive leadership style contributes significantly to the spread of uncivil behaviors (Harold & Holtz, 2015). A recent study shows that leadership behaviors that are not in line with the standards or ethics in place affect the ability of employees to perform the various tasks assigned to them (Kabat-Farr et al., 2019). On the contrary, a recent study by Walsh and his colleagues (2018) has shown that a charismatic or ethical leadership style positively influences the perception of mutual respect between team members. Lee and Jensen (2014) show that a leader who adopts a constructive leadership style can help reduce incivility at work because of their positive impact on the perception of fairness. Other research has shown that a transformational leadership style reduces the emergence and occurrence of uncivil behaviors among employees (Bureau et al., 2017; Kaiser, 2017).

In light of the studies conducted, senior executives and managers at every level should adopt appropriate and respectful behaviors (Pearson et al., 2000; Porath & Pearson, 2013) and clearly state to employees their expectations in terms of respect for internal regulations and policies (e.g., norms of respect; Walsh et al., 2012).

Limits

Although our study is supported by a sample that includes several thousand employees of a large public organization, the results that we put forward still have limits. A first major limitation would be that a cross-sectional design makes it difficult to establish causal or temporal relationships between variables. Indeed, because lower-intensity interpersonal mistreatment such as incivility is often trivialized and misunderstood by employees, it can be difficult to quantify their daily experiences in terms of observed behaviors. It would be interesting for future studies to address the relationships between selective incivility and psychological distress through a longitudinal design to better understand their dynamics from a temporal perspective. A recent meta-analysis reports that generalized incivility has a more significant impact on the health and well-being of employees over the long term than other forms of interpersonal mistreatment of greater intensity (Yao et al., 2022). Considering that employees who present marginalized identity characteristics are at greater risk of being subjected to uncivil treatment in the organization (Kabat-Farr et al., 2020), we have good reason to believe that the impact of incivility would be just as, if not more destructive to an organization and its employees in the long term than any other form of higher intensity interpersonal mistreatment.

A second limitation would be that, although the nature of the concept of incivility makes the use of self-reported questionnaires for data collection appropriate (Chan, 2009), the question of whether our results might be influenced by method variance could still be raised (Podsakoff et al., 2012). To minimize these effects as much as possible, several methodological strategies were adopted. For example, in addition to conducting Harman’s test for common method variance, we introduced the psychological distress variable and the independent variables in different sections of our questionnaire. This design makes it possible to create a “psychological separation” for our variables and is recommended to reduce the common variance effect (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Moreover, participants were assured that their questionnaires and responses would be anonymized. Nevertheless, future studies could replicate and strengthen current findings by using multiple data sources or by creating temporal separation.

A third limitation would be related to the scales used in the present study. To measure employees’ levels of psychological distress, we used three items from Kessler’s Psychological Distress Scale (K6; Kessler et al., 2002). While we initially intended to use the six items, the organization participating in the study has limited the number of questions we could include in the questionnaire. Therefore, we selected items that were representative of what we wanted to measure (i.e., employees’ experience of psychological distress). Alpha is frequently employed in assessing a scale’s internal consistency but is influenced by scale length. More importantly, alpha is not a measure of item homogeneity or unidimensionality (Schmitt, 1996). Treating single-scale scores as unidimensional when they are likely multidimensional is a notable problem in psychological research (Smith et al., 2009). Based on a discussion of mean inter-item correlations (MICs) in Simms and Watson (2007), MIC values should generally be 0.20 or higher. For the three-item version of the instrument, the Cronbach alpha of our sample was 0.86, and the Mean Inter-Item Correlation was 0.68. Both are well above the suggested values, indicating good internal consistency.

To measure uncivil behaviors in the workplace, we used the incivility subscale of the Justice Measure (Colquitt, 2001), while many have used the Workplace Incivility Scale (Cortina et al., 2001), which is presented as being among the most valid measure to assess for uncivil behaviors in organizational settings. Researchers working on negative work behaviors support a need for methodological variety to avoid being confined by one simple operationalization (Hershcovis & Reich, 2013). They also assert that it is essential to consider the context to assess the presence of negative behaviors at work (Hershcovis et al., 2020). Indeed, interpersonal relationships and social context play an essential role in the emergence of negative work behaviors (Hershcovis & Reich, 2013) and shape individual perceptions of these experiences (Hershcovis et al., 2020). Since the social context is essential to consider in order to assess the presence of negative work behaviors, the method of data collection should, as much as possible, reflect the individuals involved and their habitual behaviors, as well as behaviors that deviate from the expected standard among members of the organization (Hershcovis et al., 2020). In this sense, we collaborated with the organization participating in our research project to select the measurement scale best suited to their context and expected norms of civility/incivility and have established that the incivility subscale of the Justice Measure (Colquitt, 2001) was the best option since it was short and the items addressed incivility directly.

Finally, another limitation of the present study is that identities were treated as binaries. This was the organization’s choice. When interpreting the results of the present study, researchers should be aware that one identity might be restrictive to dress a complete portrait of one’s social experience. Indeed, the theory of intersectionality recognizes that unique lived experiences occur at the intersection of social identities (Reynoso, 2004). Nevertheless, we believe that our results highlight significant new information on the incivility experience of employees presenting physical disabilities and those from racial minorities.

Future research

Some identity characteristics are not visible at first sight but will become so over time through social interactions and processes within the team (i.e., deep-level; Harrison et al., 1998). For example, some disabilities are not “visible”. Indeed, an employee might disclose to their peers that they have ADHD or a neurocognitive disorder in a conversation. An employee could also reveal that they are struggling with a mental health problem. Once detected, colleagues could use these “invisible disabilities” to establish distinctions between “in-group” and “out-group” members (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). Future studies would benefit from focusing on these characteristics that are not visible at first sight but can become, in the long run, an anchor point for selective incivility.

Furthermore, Intersectionality theory (Crenshaw, 1991) is the idea that marginalized individuals’ social experiences have been influenced by power dynamics that are shaped by interdependent and mutual identities (e.g., gender, race, sexual orientation, disability). The theory presents that a single identity is not sufficient to understand how individuals experience negative social interactions on a daily basis (Reynoso, 2004). This theory could explain why disparities persist in our workplaces (Cortina et al., 2013). Future studies should explore identity dynamics (e.g., being a woman with a disability or someone who identifies as trans) to better understand the incivility experienced by employees and thereby intervene in a much more effective way in the face of these disrespectful mechanisms.

Conclusion

The objectives of this study were to shed light on the experiences of incivility for employees who present a marginalized identity characteristic and to measure the influence of the source of the uncivil behavior on their level of psychological distress. In sum, the results underline that employees from racial minorities and those with physical disabilities are at greater risk of experiencing incivility at work and that uncivil behaviors on the part of colleagues exert a more significant influence on their level of psychological distress than when their direct supervisor is the source of incivility at their expense. This article argues that this uncivil treatment from co-workers and direct supervisor can represent a subtle and insidious form of discrimination in the Canadian work context, reflecting the need to pay attention to low-intensity behaviors that may seem trivial. Finally, our results stress that organizations need to be vigilant on questions of “generalized” incivility because it is perhaps not as random as one would like to believe.

References

Andersson, L. M., & Pearson, C. M. (1999). Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 452–471. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1999.2202131

Baruch, Y., & Jenkins, S. (2007). Swearing at work and permissive leadership culture. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 28(6), 492–507. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730710780958

Brown, R. L. (2014). Psychological distress and the intersection of gender and physical disability: Considering gender and disability-related risk factors. Sex Roles, 71(1), 171–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0385-5

Buchanan, N. T., & Settles, I. H. (2019). Managing (in) visibility and hypervisibility in the workplace. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 113(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.11.001

Bunk, J. A., & Magley, V. J. (2013). The role of appraisals and emotions in understanding experiences of workplace incivility. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(1), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030987

Bureau, J. S., Gagné, M., Morin, A. J. S., & Mageau, G. A. (2017). Transformational leadership and incivility: A multilevel and longitudinal test. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(1–2), https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517734219. NP448-NP473

Chan, D. (2009). So why ask me? Are self-report data really that bad? Dans C. E. Lance & R. J. Vandenberg (Éds), Statistical and methodological myths and urban legends: Doctrine, verity and fable in the organizational and social sciences (pp. 309–336). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203867266-22

Chang, S. J., van Witteloostuijn, A., & Eden, L. (2010). From the editors: Common method variance in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(2), 178–184. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.88

Cloutier, E., Grondin, C., & Lévesque, A. (2018). Canadian survey on disability, 2017: Concepts and methods guide. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/89-654-X2018001

Colella, A. (2001). Co-worker distributive fairness judgments of the workplace accommodation of employees with disabilities. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 100–116. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2001.4011984

Colella, A., DeNisi, A. S., & Varma, A. (1998). The impact of ratee’s disability on performance judgments and choice as partner: The role of disability-job fit stereotypes and interdependence of rewards. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(1), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.1.102

Colella, A., & Stone, D. L. (2005). Workplace discrimination toward persons with disabilities: A call for some new research directions. In R. L. Dipboye & A. Colella (Eds), Discrimination at work: The psychological and organizational bases. Routledge (pp. 227–253). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410611567-18

Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 386–400. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.386

Cortina, L. M., Magley, V. J., Williams, J. H., & Langhout, R. D. (2001). Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and impact. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.6.1.64

Cortina, L. M., Lonsway, K. A., Magley, V. J., Freeman, L. V., Collinsworth, L. L., Hunter, M., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (2002). What’s gender got to do with it? Incivility in the federal courts. Law & Social Inquiry, 27(2), 235–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4469.2002.tb00804.x

Cortina, L. M. (2008). Unseen injustice: Incivility as modern discrimination in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 33(1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2008.27745097

Cortina, L. M., & Magley, V. J. (2009). Patterns and profiles of response to incivility in the workplace. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(3), 272–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014934

Cortina, L. M., Kabat-Farr, D., Leskinen, E. A., Huerta, M., & Magley, V. J. (2013). Selective incivility as modern discrimination in organizations: Evidence and impact. Journal of Management, 39(6), 1579–1605. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311418835

Cortina, L. M., Kabat-Farr, D., Magley, V. J., & Nelson, K. (2017). Researching rudeness: The past, present, and future of the science of incivility. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000089

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Cuddy, A. J., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2008). Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: The stereotype content model and the BIAS map. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 40(1), 61–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(07)00002-0

Deal, M. (2007). Aversive disablism: Subtle prejudice toward disabled people. Disability & Society, 22(1), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590601056667

Dhanani, L. Y., Beus, J. M., & Joseph, D. L. (2018). Workplace discrimination: A meta-analytic extension, critique, and future research agenda. Personnel Psychology, 71(2), 147–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12254

Di Matteo, L. (2022). Times have changed: public-sector employment on the rise in Canada, especially in Ontario. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/article/times-have-changed-public-sector-employment-on-the-rise-in-canada-especially-in-ontario

Dovidio, J. F., Gaertner, S. L., & Bachman, B. A. (2001). Racial bias in organizations: The role of group processes in its causes and cures. In M. E. Turner (Ed.), Groups at work: Theory and research (pp. 415–444). Erlbaum, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315805986-25

Dovidio, J. F., Kawakami, K., & Gaertner, S. L. (2002). Implicit and explicit prejudice and interracial interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.62

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.109.3.573

Fiske, S. T. (2000). Stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination at the seam between the centuries: Evolution, culture, mind, and brain. European Journal of Social Psychology, 30(3), 299–322. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1099-0992(200005/06)30:3%3C299::aid-ejsp2%3E3.0.co;2-f

Foulk, T., Woolum, A., & Erez, A. (2016). Catching rudeness is like catching a cold: The contagion effects of low-intensity negative behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(1), 50–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000037

Fox, S. A., & Giles, H. (1996). Interability communication: Evaluating patronizing encounters. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 15(3), 265–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927x960153004

Furukawa, T. A., Kessler, R. C., Slade, E. T., & Andrews, G. (2003). The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Psychological Medicine, 33(2), 357–362. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291702006700

Geldart, S., Langlois, L., Shannon, H. S., Cortina, L. M., Griffith, L., & Haines, T. (2018). Workplace incivility, psychological distress, and the protective effect of co-worker support. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 11(2), 96–110. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijwhm-07-2017-0051

Giumetti, G. W., Hatfield, A. L., Scisco, J. L., Schroeder, A. N., Muth, E. R., & Kowalski, R. M. (2013). What a rude e-mail! Examining the differential effects of incivility versus support on mood, energy, engagement, and performance in an online context. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(3), 297–309. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032851

Gonzalez, J. A., & DeNisi, A. S. (2009). Cross-level effects of demography and diversity climate on organizational attachment and firm effectiveness. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.498

Han, S., Harold, C. M., Oh, I., Kim, J. K., & Agolli, A. (2022). A meta-analysis integrating 20 years of workplace incivility research: Antecedents, consequences, and boundary conditions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(3), 497–523. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2568

Harold, C. M., & Holtz, B. C. (2015). The effects of passive leadership on workplace incivility. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(1), 16–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1926

Harrison, D. A., Price, K. H., & Bell, M. P. (1998). Beyond relational demography: Time and the effects of surface- and deep-level diversity on work group cohesion. Academy of Management Journal, 41(1), 96–107. https://doi.org/10.5465/256901

Hayes, T. L., Kaylor, L. E., & Oltman, K. A. (2020). Coffee and controversy: How applied psychology can revitalize sexual harassment and racial discrimination training. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 13(2), 117–136. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2019.84

Heilman, M. E., & Okimoto, T. G. (2007). Why are women penalized for success at male tasks?: The implied communality deficit. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.81

Hershcovis, M. S. (2011). Incivility, social undermining, bullying… oh my! “: A call to reconcile constructs within workplace aggression research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(3), 499–519. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.689

Hershcovis, M. S., & Barling, J. (2010). Towards a multi-foci approach to workplace aggression: A meta‐analytic review of outcomes from different perpetrators. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(1), 24–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.621

Hershcovis, M. S., Cortina, L. M., & Robinson, S. L. (2020). Social and situational dynamics surrounding workplace mistreatment: Context matters. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(8), 699–705. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2479

Hershcovis, M. S., & Reich, T. C. (2013). Integrating workplace aggression research: Relational, contextual, and method considerations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(S1), S26–S42. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1886

Hogg, M. A., & Turner, J. C. (1985). Interpersonal attraction, social identification and psychological group formation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 15(1), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420150105

Hughes, R., Swedlund, N., Petersen, N., & Nosek, M. (2001). Depression and women with spinal cord injury. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, 7(1), 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1310/hpkx-d0pv-mnfv-n349

Jones, E. E., Farina, A., Hastorf, A. H., Markus, H., Miller, O. T., Scott, R. A., & de Sales-French, R. (1984). Social stigma: The psychology of marked relationships. Freeman.

Jones, K. P., Arena, D. F., Nittrouer, C. L., Alonso, N. M., & Lindsey, A. P. (2017). Subtle discrimination in the workplace: A vicious cycle. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 10(1), 51–76. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2016.91

Kabat-Farr, D., & Cortina, L. M. (2014). Sex-based harassment in employment: New insights into gender and context. Law and Human Behavior, 38(1), 58–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000045

Kabat-Farr, D., Cortina, L. M., & Marchiondo, L. A. (2018). The emotional aftermath of incivility: Anger, guilt, and the role of organizational commitment. International Journal of Stress Management, 25(2), 109–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000045

Kabat-Farr, D., & Labelle-Deraspe, R. (2022). Five ways to reduce rudeness in the remote workplace: Don’t let incivility hide behind a keyboard. In Virtual EI (pp.109–129). Harvard Business Review Press.

Kabat-Farr, D., Settles, I. H., & Cortina, L. M. (2020). Selective incivility: An insidious form of discrimination in organizations. Equality Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 39(3), 253–260. https://doi.org/10.1108/edi-09-2019-0239

Kabat-Farr, D., Walsh, B. M., & McGonagle, A. K. (2019). Uncivil supervisors and perceived work ability: The joint moderating roles of job involvement and grit. Journal of Business Ethics, 156(4), 971–985. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3604-5

Kaiser, J. A. (2017). The relationship between leadership style and nurse-to‐nurse incivility: Turning the lens inward. Journal of Nursing Management, 25(2), 110–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12447

Kanter, R. M. (1977). Some effects of proportions on group life. In P. P. Rieker & E. H. Carmen (Eds.), The gender gap in psychotherapy (pp. 53–78). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-4754-5_5

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291702006074

Kessler, R. C., Barker, P. R., Colpe, L. J., Epstein, J. F., Gfroerer, J. C., Hiripi, E., Howes, M. J., Normand, S. L. T., Manderscheid, R. W., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2003). Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(2), 184–189. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184

Lee, J., & Jensen, J. M. (2014). The effects of active constructive and passive corrective leadership on workplace incivility and the mediating role of fairness perceptions. Group & Organization Management, 39(4), 416–443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601114543182

Lim, S., & Cortina, L. M. (2005). Interpersonal mistreatment in the workplace: The interface and impact of general incivility and sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(3), 483–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.3.483

Lim, S., & Lee, A. (2011). Work and nonwork outcomes of workplace incivility: Does family support help? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(1), 95–111. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021726

Lyubykh, Z., Turner, N., Barling, J., Reich, T. C., & Batten, S. (2020). Employee disability disclosure and managerial prejudices in the return-to-work context. Personnel Review, 50(2), 770–788. https://doi.org/10.1108/pr-11-2019-0654

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4

McCord, M. A., Joseph, D. L., Dhanani, L. Y., & Beus, J. M. (2018). A meta-analysis of sex and race differences in perceived workplace mistreatment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(2), 137–163. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000250

Miner, K. N., Pesonen, A. D., Smittick, A. L., Seigel, M. L., & Clark, E. K. (2014). Does being a mom help or hurt? Workplace incivility as a function of motherhood status. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19(1), 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034936

Nosek, M. A., & Hughes, R. B. (2003). Psychosocial issues of women with physical disabilities. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin, 46(4), 224–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/003435520304600403

Oyet, M. C., Arnold, K. A., & Dupré, K. E. (2019). Differences among women in response to workplace incivility: Perceived dissimilarity as a boundary condition. Equality Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 39(3), 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1108/edi-06-2018-0108

Park, L. S., & Martinez, L. R. (2022). An “I” for an “I”: A systematic review and meta-analysis of instigated and reciprocal incivility. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 27(1), 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000293

Pearson, C. M., Andersson, L. M., & Porath, C. L. (2000). Assessing and attacking workplace incivility. Organizational Dynamics, 29(2), 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0090-2616(00)00019-x

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Porath, C., & Pearson, C. (2013). The price of incivility. Harvard Business Review, 91(1–2), 114–121. https://hbr.org/2013/01/the-price-of-incivility

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., & Levin, S. (2006). Social dominance theory and the dynamics of intergroup relations: Taking stock and looking forward. European Review of Social Psychology, 17(1), 271–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463280601055772

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods Instruments & Computers, 36(4), 717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03206553

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.40.3.879

Reynoso, J. (2004). Perspectives on intersections of race, ethnicity, gender, and other grounds: Latinas at the margins. Harvard Latino Law Review, 7(1), 63–73.

Richman, J. A., Rospenda, K. M., Nawyn, S. J., Flaherty, J. A., Fendrich, M., Drum, M. L., & Johnson, T. P. (1999). Sexual harassment and generalized workplace abuse among university employees: Prevalence and mental health correlates. American Journal of Public Health, 89(3), 358–363. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.89.3.358

Rosen, C. C., Koopman, J., Gabriel, A. S., & Johnson, R. E. (2016). Who strikes back? A daily investigation of when and why incivility begets incivility. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(11), 1620–1634. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000140

Schilpzand, P., De Pater, I. E., & Erez, A. (2016). Workplace incivility: A review of the literature and agenda for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(1), S57–S88. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1976

Schmitt, N. (1996). Uses and abuses of coefficient alpha. Psychological Assessment, 8(4), 350–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.8.4.350

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (2001). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. Cambridge University Press.

Simms, L. J., & Watson, D. (2007). The construct validation approach to personality scale construction. In R. W. Robins, R. C. Fraley, & R. F. Krueger (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in personality psychology (pp. 240–258). The Guilford Press.

Smith, G. T., McCarthy, D. M., & Zapolski, T. C. (2009). On the value of homogeneous constructs for construct validation, theory testing, and the description of psychopathology. Psychological Assessment, 21(3), 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016699

Stone, D. L., & Colella, A. (1996). A model of factors affecting the treatment of disabled individuals in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 21(2), 352–401. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1996.9605060216

Sue, D. W., Alsaidi, S., Awad, M. N., Glaeser, E., Calle, C. Z., & Mendez, N. (2019). Disarming racial microaggressions: Microintervention strategies for targets, White allies, and bystanders. American Psychologist, 74(1), 128–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000296

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.62.4.271

Sumpter, D. M. (2019). Bro or kook? The effect of dynamic member evaluation on incivility and resources in surf lineups. Equality Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 39(3), 261–284. https://doi.org/10.1108/edi-04-2018-0075

Swim, J. K., Aikin, K. J., Hall, W. S., & Hunter, B. A. (1995). Sexism and racism: Old-fashioned and modern prejudices. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(2), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.2.199

Tajfel, H. (1974). Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Social Science Information, 13(2), 65–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847401300204

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin, & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel, & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (2nd ed., pp. 7–24). Nelson-Hall, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203505984-16

Tehseen, S., Ramayah, T., & Sajilan, S. (2017). Testing and controlling for common method variance: A review of available methods. Journal of Management Sciences, 4(2), 142–168. https://doi.org/10.20547/jms.2014.1704202

Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (2020). 2020 Public service employee survey. https://www.canada.ca/en/treasury-board-secretariat/services/innovation/public-service-employee-survey/2020.html

Walsh, B. M., Lee, J. J., Jensen, J. M., McGonagle, A. K., & Samnani, A. K. (2018). Positive leader behaviors and workplace incivility: The mediating role of perceived norms for respect. Journal of Business and Psychology, 33(4), 495–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-017-9505-x

Walsh, B. M., Magley, V. J., Reeves, D. W., Davies-Schrils, K. A., Marmet, M. D., & Gallus, J. A. (2012). Assessing workgroup norms for civility: The development of the Civility Norms Questionnaire-Brief. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27(4), 407–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-011-9251-4

World Health Organization & World Bank. (2011). Summary: World report on disability 2011. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70670

Yao, J., Lim, S., Guo, C. Y., Ou, A. Y., & Ng, J. W. X. (2022). Experienced incivility in the workplace: A meta-analytical review of its construct validity and nomological network. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(2), 193–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000870

Zou, C., Opasina, O., Borova, B., & Parkin, A. (2022). Experiences of discrimination at work. https://fsc-ccf.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Experiences_of_Discrimination_at_Work.pdf

Acknowledgements

The authors declare none.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Labelle-Deraspe, R., Mathieu, C. Exploring incivility experiences of marginalized employees: implications for psychological distress. Curr Psychol 43, 5163–5178 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04470-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04470-y