Abstract

The majority of workplace incivility research has focused on implications of such acts for victims and observers. We extend this work in meaningful ways by proposing that, due to its norm-violating nature, incivility may have important implications for perpetrators as well. Integrating social norms theory and research on guilt with the behavioral concordance model, we take an actor-centric approach to argue that enacted incivility will lead to feelings of guilt, particularly for prosocially-motivated employees. In addition, given the interpersonally burdensome as well as the reparative nature of guilt, we submit that incivility-induced guilt will be associated with complex behavioral outcomes for the actor across both home and work domains. Through an experience sampling study (Study 1) and two experiments (Studies 2a and 2b), we found that enacting incivility led to increased feelings of guilt, especially for those higher in prosocial motivation (Studies 1 and 2a). In addition, supporting our expectations, Study 1 revealed that enacted incivility—via guilt—led to increased venting to one’s spouse that evening at home, increased performance the next day at work, as well as decreased enacted incivility the next day at work. Our findings demonstrate that enacted incivility has complex effects for actors that span the home and work domains. We discuss the theoretical and practical implications of our results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

For many employees, incivility is unfortunately a common experience at work (Porath & Pearson, 2012; Rosen et al., 2016). For example, one poll conducted across 14 years suggested that 98% of employees had experienced incivility at work, and a 2011 survey showed that 50% of respondents reported experiencing rudeness at least once a week (Porath & Pearson, 2013). Workplace incivility involves rude behaviors that violate social norms and is characterized by disregard for others (Andersson & Pearson, 1999; for a recent meta-analysis, see Yao et al., 2022). Since the introduction of this construct by Cortina and colleagues (2001), the literature has carefully examined the consequences that accrue to targets of this pernicious behavior (Schilpzand et al., 2016), such as increased stress (Bowling & Beehr, 2006), decreased work effort (Porath & Pearson, 2013), as well as reduced performance (Porath & Pearson, 2013).

Yet, notably absent from this literature is an in-depth discussion of how incivility impacts actors (e.g., Schilpzand et al., 2016). Indeed, in stark contrast to the richness of the literature on targets, the literature on instigators has largely focused on either stable predictors of rudeness (e.g., Park & Martinez, 2022), or on the relatively predictable interpersonal sanctions that are subsequently incurred by rude actors (e.g., Foulk et al., 2016; Scott et al., 2013; Su et al., 2022). However, incivility may lead to both emotional and behavioral outcomes for the perpetrator that go past the rude incident and permeate social contexts (e.g., Klass, 1978; Van Kleef et al., 2015). Little research has considered this perspective (see Hülsheger et al., 2021 for an exception), which underscores an assumption in the literature that, since incivility is a “low-intensity deviant (rude, discourteous) behavior with ambiguous intent to harm the target” (Pearson et al., 2005: 179), its enactment may not impact the perpetrator significantly, or its effects may be temporary and isolated to a particular episode. Indeed, a hallmark notion in incivility research is that this behavior is often innocuous for the perpetrator and covert in nature (e.g., Lim et al., 2018).

This prevailing perspective may be short-sighted, however, because incivility violates social norms for mutual respect (e.g., Cortina et al., 2001; Pearson et al., 2005; Schilpzand et al., 2016), and perpetrators are likely to look back on such behaviors with regret (e.g., Van Kleef et al., 2015). Therefore, constraining the consequences of enacted incivility to the reactions of others paints an overly simplistic picture of this phenomenon (i.e., actors will be punished by others). Instead, there are theoretical and practical reasons to believe that the reality involving incivility may be more complex for perpetrators, highlighting the need to better understand both the consequences that accrue to actors of incivility, as well as their subsequent responses to such acts.

Furthermore, most of the existing research on instigated incivility has taken between-person examinations of the phenomenon (e.g., Park & Martinez, 2022; Taylor et al., 2022). Incivility, however, is often enacted in response to daily experiences at work (e.g., Andersson & Pearson, 1999; Meier & Gross, 2015; Rosen et al., 2016; Van Jaarsveld et al., 2010), suggesting that actors’ responses to such acts may vary across days and contexts. There is consensus in the literature that workplace incivility is a negative experience for most involved (e.g., Schilpzand et al., 2016), but little is known about how perpetrators may subsequently react to the negative emotions that typically accompany such events or how they may try to repair such negative behaviors across days at work. Accordingly, we need to better understand the daily and event-based nature of incivility (e.g., Cortina et al., 2017; Schilpzand et al., 2016; Woolum et al., 2024) by adopting a comprehensive lens that examines why and how perpetrators may manage and try to repair their uncivil behavior across days at work. To investigate these possibilities, we integrate social norms theory (Gross & Vostroknutov, 2022; Van Kleef et al., 2015, 2019) with the literature on guilt (Baumeister et al., 1994; Tangney et al., 2007) as well as research on behavioral concordance (Moskowitz & Coté, 1995) to provide a holistic view on why enacted incivility may influence the actor, how its effects may manifest across different social domains, as well as for whom these effects may be more pronounced (e.g., Whetten, 1989).

Extant scholarship posits that violations of social norms may trigger feelings of guilt in actors (Baumeister et al., 1994; McGraw, 1987; Van Kleef et al., 2015)—perceptions of falling short of moral standards in a domain (Lindsay-Hartz, 1984). Since enacting incivility violates workplace norms of propriety and professional conduct (e.g., Pearson et al., 2001), we propose that such acts may be associated with feelings of guilt. At the same time, we recognize that not all actors are likely to experience this state to the same extent. That is, although many individuals may enact incivility on a given day (e.g., Hülsheger et al., 2021; Rosen et al., 2016), the behavioral concordance framework suggest that the consequences of incivility may be magnified for some employees (e.g., Moskowitz & Coté, 1995). Specifically, the behavioral concordance model argues that discordance between one’s traits and one’s behaviors leads to stronger negative affective reactions (Moskowitz & Coté, 1995). According to this model, higher levels of guilt may be experienced by employees for whom incivility is trait-discordant. As incivility is an antisocial behavior, we looked to prosocial motivation as a trait that may exacerbate the feelings of guilt resulting from enacted incivility.

Research on guilt further posits that, as a moral emotion, guilt may result in both burdensome as well as reparative consequences for the individual (e.g., Baumeister et al., 1995; Flynn & Schaumberg, 2012; Tangney et al., 1996). Indeed, it is the theoretical juxtaposition of the positives and negatives of guilt which suggests that the enactment of incivility may be more complex than has been previously acknowledged in the literature. In capturing this complexity, we are guided by research positing that individuals may manage their emotions differently across different domains based on social cues and motivations present in those domains (Greenaway et al., 2018; Matthews et al., 2021), and we accordingly examine the effects of incivility-induced guilt across both the home and work contexts. We expect that incivility-induced guilt may manifest its burdensome nature at home (a context with more lax requirements for emotional expressions) and its reparative nature at work (a context where norm-adherence is consequential).

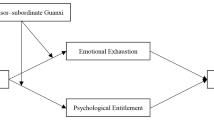

Specifically, at home, perpetrators of incivility may discharge their guilt on their partners via venting, an emotional-based form of coping (Baer et al., 2018; Brown et al., 2005; Rosen et al., 2021), because employees feel more comfortable managing their negative emotions in this setting (e.g., Lanaj et al., 2018; Lively & Powell, 2006) and because venting often targets close others not involved in the incident (Behfar et al., 2020; Rimé et al., 1992). In contrast, the social norms literature suggests that, at work, feelings of guilt are likely to motivate reparative behaviors and a reduction of future transgressions as perpetrators try to re-align their behavior with workplace norms (Van Kleef et al., 2015). This is because work is where the act of incivility occurred and there are potential negative repercussions that exist in this context (e.g., Hülsheger et al., 2021; Scott et al., 2013). In particular, employees strive to uphold two key norms at work—fulfilling their task responsibilities (Carpini et al., 2017) and refraining from violating social norms of interpersonal conduct (Pearson et al., 2001). Thus, drawing from theory on norms, to capture perpetrators’ attempts to re-align with task-based norms at work, we focused on subsequent task performance, and to capture re-alignment with interpersonal norms at work, we focused on the reduction of subsequent enacted incivility (e.g., Baumeister et al., 1994; Van Kleef et al., 2015). In all, our integrated framework speaks to the complex and cross-domain effects that enacted incivility may have on actors. Figure 1 depicts our conceptual model.

Our work offers several theoretical contributions to the literature on incivility. First, we contribute to recent research adopting an actor-centric perspective in investigating the intrapersonal and behavioral effects of daily incivility for actors and provide a richer understanding of the consequences of such acts at work (e.g., Hülsheger et al., 2021; Park & Martinez, 2022; Taylor et al., 2022; Zhong & Robinson, 2021). In so doing, we expand our theoretical knowledge of this behavior and elucidate its multifaceted implications for employees. Second, we take a holistic, dual domains approach by investigating not only how incivility influences actors’ emotions at work, but also how—via guilt—such acts impact actors’ interactions at home, as well as their behaviors the next day at work. Showing that work experiences may interfere with interactions at home is particularly relevant given the increasing trend for more employees to work in hybrid formats (e.g., from the office and home) (Smart, 2024), where work and home experiences become closely intertwined. We identify guilt as a key mechanism through which enacted incivility can become a complex experience for actors with simultaneously interpersonally burdensome as well as reparative consequences across the work and home domains. Third, by drawing on the behavioral concordance model and the prosocial motivation literature, we identify for whom the complex effects of enacted incivility may be even more pronounced. While social norms theory suggests that individuals are generally likely to experience feelings of guilt following uncivil behavior (Van Kleef et al., 2015), we find that people who care about benefiting others because of their predilection to be prosocial may suffer the most from these acts.

Theory and Hypotheses Development

Enacted Incivility and Guilt

Social norms theory posits that norms—how individuals generally behave as well as how they are expected to behave in a given context—play an important role in driving individuals’ behavior in social settings (Gross & Vostroknutov, 2022; Van Kleef et al., 2015, 2019). Given that workplace incivility includes behaviors such as ignoring and disrespecting coworkers, disregarding their opinions, and spreading harmful rumors (Pearson et al., 2001), such acts violate norms of proper conduct at work (Pearson et al., 2001). The counter-normative nature of incivility at work may render this experience costly for actors because individuals are motivated to adhere to salient contextual norms (Gross & Vostroknutov, 2022; Van Kleef et al., 2015, 2019), and behaviors that transgress moral standards in a given context are often associated with negative psychological and affective outcomes (Klass, 1978; Van Kleef et al., 2015). Accordingly, our theoretical framework—informed by both social norms theory (Van Kleef et al., 2015) as well as research on guilt (Baumeister et al., 1994; Tangney et al., 2007)—suggests that enacting incivility may be associated with increased feelings of guilt.

In particular, social norms theory suggests that interpersonal transgressions, owing to their norm-violating character, can result in emotional distress that manifests as guilt, a moral emotion characterized by an appraisal of the wrongness of one’s actions or thoughts (Lewis, 1971; Lindsay-Hartz, 1984; Tangney & Dearing, 2003; Van Kleef et al., 2015). Acts of incivility can be distressing to others because they convey “breaches of etiquette, professional misconduct and moral decay,” thus conspicuously violating norms of cooperation and mutual camaraderie at work (Pearson et al., 2001: 1397). Therefore, it is possible that feelings of guilt will function as a form of salient feedback alerting perpetrators of incivility of the misalignment of their behavior with salient standards at work (e.g., Tangney et al., 2007). Accordingly, we examined guilt as a key emotional response associated with enacted incivility.Footnote 1 Supporting these ideas, organizational research has shown that workplace transgressions akin to incivility such as abusive behaviors (Liao et al., 2018) and counterproductive workplace behaviors (Ilies et al., 2013) result in increased feelings of guilt, potentially because of the harm that these behaviors may cause to the maintenance of positive interpersonal relationships at work. In line with these thoughts, we propose:

Hypothesis 1

Enacted incivility toward coworkers may be associated with increased feelings of guilt.

The Moderating Role of Prosocial Motivation

Incivility is often preceded by interpersonal experiences and situational factors (e.g., Meier & Gross, 2015; Park & Martinez, 2022; Rosen et al., 2016) and fluctuates substantially within-person (Hülsheger et al., 2021; Rosen et al., 2016), suggesting that many individuals may enact incivility on a given day, regardless of their disposition. Theory on behavioral concordance, however, gives us reason to believe that certain individuals may be more sensitive to the negative outcomes of enacted incivility (Moskowitz & Coté, 1995). Specifically, the behavioral concordance model posits that when individuals engage in behaviors that run counter to their disposition, they are likely to experience heightened subsequent negative affective states (Moskowitz & Coté, 1995), as individuals value self-consistency (Blasi, 1983) and are uncomfortable with discordant behaviors (e.g., Koopman et al., 2021). Given that incivility is a decidedly antisocial behavior, we examine how prosocial motivation influences actors’ affective reactions to their enacted incivility.

Prosocial motivation captures individuals’ desire to benefit others through their acts (Grant & Berry, 2011). Thus, from a behavioral concordance lens, such a tendency is decidedly at odds with acts that violate social norms and that reveal a disregard for others, as manifested in incivility (Cortina et al., 2001), and the discordance may result in subsequent negative affective states. This resulting affective state may be best indicated by guilt because incivility harms others and runs counter to prosocial values (e.g., Grant & Berry, 2011; Tracy et al., 2007), and is likely to elicit reflections on one’s negative behaviors, as suggested by social norms theory and research on guilt (Baumeister et al., 1994; Van Kleef et al., 2015). Moreover, given that incivility is low in intensity and characterized by ambiguous intent to harm (Pearson et al., 2005), it is possible that not all individuals may be fully aware of the harmful nature of their uncivil behaviors. That said, prosocial motivation is associated with greater perspective taking (Grant & Berry, 2011), as prosocially-motivated employees are likely to pay close attention to the perspective of others in social interactions (De Dreu, 2006). Accordingly, on days when prosocially-motivated employees enact incivility toward coworkers, they are likely to be more aware of the harm that they caused with their rude behavior, thus amplifying the subsequent feelings of guilt that typically accompany such acts. Together, these ideas suggest that following enactment of incivility, individuals higher (vs. lower) in prosocial motivation may experience more guilt (a) because of the psychological misalignment between such acts and their predilection to benefit others, and (b) because of their heightened awareness of the harm that they may have caused via their incivility. Consistent with these ideas, we posit the following:

Hypothesis 2

Enacted incivility toward coworkers is associated with more guilt for employees who are higher (vs. lower) in prosocial motivation.

Behavioral Outcomes of Incivility-Induced Guilt

Guilt is a complex moral emotion whose function is to provide both punishment to the self for unacceptable behavior, as well as motivation to the self for repairing one’s behavior, because those who experience guilt are “drawn to consider their behavior and its consequences” (Tangney et al., 2007: 5). Thus, on the one hand, guilt acts as a burdensome and distressing emotion (Baumeister et al., 1994; Wicker et al., 1983), described as pain-evoking, tense, and deserving of punishment (Bastian et al., 2011; Wicker et al., 1983), and research shows that individuals experiencing such aversive emotions often work hard to manage them (Gross, 1998; Tice & Bratslavsky, 2000). On the other hand, guilt also acts as a reparative emotion that motivates individuals to proactively amend their transgressions by realigning their behaviors with salient standards in the context in which the misdeed occurred (e.g., Baumeister et al., 1994; Lindsay-Hartz, 1984; Tangney et al., 2007; Van Kleef et al., 2015). Supporting these ideas, research suggests that although guilt can lead to paralyzing or destructive behavior (Kim et al., 2011; Sheehy et al., 2019), it may also motivate effortful endeavor to restore one’s social standing following a transgression (Flynn & Schaumberg, 2012). Applied to our context, theory on guilt suggests that incivility-induced guilt may be similarly complex and may manifest both in attempts to manage feelings of guilt as well as in efforts to repair transgressions.

We investigate employees’ reactions to incivility-induced guilt in two important social domains—at home as well as at work. We examined the outcomes of incivility-induced guilt across both domains because contextual constraints and expectations play a large role in determining how individuals express their negative emotions (Greenaway et al., 2018; Matthews et al., 2021). A joint examination of the home and work domains is likely to provide unique insights into the behavioral implications of incivility-induced guilt because, compared to home, there are stronger norms for professionalism and self-regulation at work, as well as higher reputational costs (e.g., Moran et al., 2013; Wharton & Erickson, 1993).

The home domain is important to study in the context of enacted incivility because negative work experiences akin to incivility tend to follow people home (ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012) and have persistent after-work effects on their attitudes (Foulk et al., 2018; Ilies et al., 2007; Yuan et al., 2018). In addition, because the home environment feels safer and has lower costs as well as more flexible norms for emotional expressions (Lively & Powell, 2006; Moran et al., 2013), perpetrators of incivility may feel more comfortable sharing their negative emotions and experiences when at home (e.g., Lanaj et al., 2018; Lively & Powell, 2006). At the same time, the work domain is also relevant to study because guilt motivates reparative behaviors in the context where the transgression occurred (Baumeister et al., 1994; Van Kleef et al., 2015). Incivility breaks social norms and jeopardizes perpetrators’ relationships with colleagues at work (Pearson et al., 2001; Schilpzand et al., 2016), which may incentivize them to engage in reparative behaviors that aim to restore their standing in the workplace (Flynn & Schaumberg, 2012; Schmader & Lickel, 2006; Scott et al., 2013), such as by working harder and refraining from further acts of incivility. Accordingly, in capturing the complexity of guilt across both domains, we expect that incivility-induced guilt will trigger interpersonally burdensome behaviors at home in the form of venting, as well as reparative behaviors the next day at work in the form of heightened task performance and reduced incivility.

Incivility-Induced Guilt and Venting

Venting is a fairly common emotion-focused coping mechanism (Alicke et al., 1992) prompted by negative interpersonal events (e.g., Behfar et al., 2020; Farley et al., 2022) that involves letting out one’s negative emotions to others (Rosen et al., 2021). Venting is particularly relevant in the aftermath of incivility-induced guilt, as the sense-making literature emphasizes that negative emotions (such as guilt) that are elicited by counter-normative situations (such as the enactment of incivility) can trigger sense-making processes to manage such burdensome feelings. Given that venting is a form of sense-making (e.g., Behfar et al., 2020), individuals who enact incivility at work may look to manage and make sense of their counter-normative behaviors and feelings of guilt by venting to partners when at home (e.g., Baer et al., 2018; Brown et al., 2005; Parlamis, 2012; Volkema et al., 1996). Indeed, there is evidence showing that, following negative emotional episodes, individuals tend to share negative feelings with others who are not directly involved in the incident (Behfar et al., 2020; Rimé et al., 1992). Furthermore, individuals tend to disclose emotions mostly to intimate others, such as family members or spouses (Rimé et al., 1992). These arguments suggest that when individuals experience feelings of guilt due to acting with incivility at work, they may engage in more venting toward their spouse in the evening at home. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 3

Guilt will (a) be associated with increased venting to spouses at home and (b) mediate the association between enacted incivility and venting.

Incivility-Induced Guilt and Reparative Behaviors

In the work domain, the reputational costs of acting with incivility (e.g., Scott et al., 2013) may motivate guilty actors to try and repair their standing by working harder to realign their behaviors with salient work norms (e.g., Flynn & Schaumberg, 2012; Schmader & Lickel, 2006; Tangney et al., 2007; Van Kleef et al., 2015). Given that workplace norms consist of both task-based and social expectations (e.g., Carpini et al., 2017; Scott et al., 2013), feelings of guilt may induce reparative efforts toward achieving both goals, in the form of subsequent heightened task performance and reduced incivility. These expectations also align with research on guilt, which suggests that the reparative nature of guilt has a broader scope encompassing both interpersonal and task domains (Baumeister et al., 1994).

Task role expectations include fulfilling one’s job description (Murphy & Jackson, 1999) as well as achieving a variety of performance metrics (e.g., Griffin et al., 2007). Theory on guilt suggests that guilt’s reparative motivation can activate a general approach orientation that includes the task domain because guilt is associated with feelings of personal responsibility (Tangney, 1991) and motivates individuals to exert extra effort toward pursuing salient expectations (e.g., Flynn & Schaumberg, 2012; Tignor & Colvin, 2019). Given the significant task-based expectations that exist at work (e.g., Carpini et al., 2017), the reparative nature of guilt has often been linked to task-based effort as guilty individuals engage more with their jobs to repair their misdeeds (e.g., Flynn & Schaumberg, 2012; Grant & Wrzesniewski, 2010; Haran, 2019). Consistent with these arguments, we expect that guilt due to incivility may enhance subsequent task performance.

In addition to task-based expectations, most workplaces also have norms for respectful social exchanges among coworkers (e.g., Pearson et al., 2001; Scott et al., 2013). These norms, however, are violated by acts of incivility (Pearson et al., 2001), and for this reason, transgressors are often ostracized for their counter-normative behaviors (Scott et al., 2013). In light of such norms, individuals who feel guilty from acting with incivility toward coworkers may also seek to more directly realign their behavior with what is expected of them at work (e.g., Baumeister et al., 1994; Lindsay-Hartz, 1984; Tangney et al., 2007) by reducing their subsequent incivility. Consistent with these ideas, previous research suggests that guilt leads to a decrease in subsequent negative behaviors in attempts to rectify the initial misdeed (Amodio et al., 2007; Baumeister et al., 1995). Therefore, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 4

Guilt will (a) be associated with increased next-day performance at work and (b) mediate the association between enacted incivility and next-day performance.

Hypothesis 5

Guilt will (a) be associated with reduced next-day incivility at work and (b) mediate the association between enacted incivility and next-day incivility.

Overview of Studies

To test our hypotheses, we ran three complementary studies. Given that incivility fluctuates from day to day within individuals (Hülsheger et al., 2021; Rosen et al., 2016; Tremmel & Sonnentag, 2018), in Study 1 we conducted a daily experience sampling method (ESM) study where we captured the naturally fluctuating experiences of employees over a span of three work weeks. In this study we tested the effects of enacted incivility on guilt (Hypothesis 1) and the moderating effect of prosocial motivation on this association (Hypothesis 2) in a work setting. In addition, we examined the complex downstream outcomes of enacted incivility for the actor by testing its effects on venting that night at home (Hypothesis 3), as well as task performance (Hypothesis 4) and enacted incivility (Hypothesis 5) the next day at work. Study 2a is an experiment where we manipulated enacted incivility and replicated the effect of enacted incivility on guilt (Hypothesis 1) and the moderating effect of prosocial motivation on the association between enacted incivility and guilt (Hypothesis 2). We conducted this study to accomplish two goals: (a) to reduce concerns of reverse causality by relying on an experimental approach, and (b) to take an event-based approach to incivility (e.g., Cortina et al., 2017; Schilpzand et al., 2016; Woolum et al., 2024). Study 2b is an experiment that constructively builds on Study 2a by exploring whether effects of enacted incivility on guilt depend on the perpetrator’s feelings of justification—a question that emerged during the review process.Footnote 2

Study 1: Method

Syntax and output for primary analyses across all studies are available in an OSF repository.Footnote 3 In this repository, we describe our sampling plan, include the exact wording for the manipulations used, and show measures for each study.

Participants and Procedure

We recruited participants from universities and local companies in the Midwest (United States), drawing administrative and technical staff from two universities and additional employees from local companies (for a similar example of such recruitment procedures, please see Tepper et al., 2018).Footnote 4Footnote 5 We invited participants via mass email to participate in a daily ESM study, offering up to $70 based on their survey completion rate.Footnote 6 In the email, employees were directed to an initial sign-up survey in which they filled out their consent form (University of Cincinnati IRB 2016-0563: “Daily Workplace Experiences”), reported their demographic information and their levels of prosocial motivation, along with an email address for their spouse. In addition, we asked the employees to pass on the recruitment email to other employees who may be interested in participating. We emailed spouses with a separate sign-up survey containing their consent form and demographic questions (we offered up to $30 for participation). A week later we began conducting the daily portion of the study, and surveyed participants three times a day for 15 consecutive workdays. We asked participating employees to complete the first survey in the morning before starting work, the second survey in the afternoon right after they came off from work, and the third survey in the evening at home. We also asked spouses to complete their survey in the evening on those same days. At each survey time, we emailed participants with a reminder as well as a personal link to the corresponding survey. Focal employees completed their morning survey, on average, at 8:29 AM, and it contained control measures of positive and negative affect. They completed the afternoon survey, on average, at 4:24 PM, and it assessed task performance and enacted incivility that day. They completed the evening survey, on average, at 8:25 PM, and it assessed their feelings of guilt and shame (as a control). Spouses completed their survey in the evening, on average, at 8:28 PM, and it measured the degree of venting that the focal employee had engaged in since coming home from work that evening. On average, the time elapsed between the employee morning and afternoon surveys was 7 h and 55 min, and the time elapsed between the employee afternoon and evening surveys was 4 h and 1 min.

One-hundred and twenty-five focal employees and their spouses signed up to participate in the daily study. We excluded 18 employees for failing to complete at least 3 days of surveys (e.g. Gabriel et al., 2018). The final sample consisted of 107 employees, with a total of 1115 day-level observations (response rate of 69.5%). Employees in the sample worked in a variety of positions ranging from administrative, clerical, technical, and service jobs. Of the employees, 23 identified as male, while 101 identified as Caucasian, 4 as African American, 1 as Middle Eastern/West Asian, and 1 as Hispanic. On average, employees worked 40.7 h weekly (SD = 5.2), and their average organizational tenure was 7 years and 5 months (SD = 7.3 years). Of the spouses, 21 identified as female, 93 identified as Caucasian, 5 as African American, 3 as Hispanic, 2 as Asian, 1 as Native American, and 2 as multi-racial. Participants worked in a variety of industries, such as healthcare, information technology, education, as well as finance.

Measures

Unless noted otherwise, all measures in Study 1 used items that were rated on a 5-point scale (1 = “Not at All,” to 5 = “Very Much”).

Between-Person Measure: Prosocial Motivation

We measured prosocial motivation in the study sign-up survey with four items developed by Grant (2008). The items were: “I care about benefitting others through my work,” “I want to help others through my work,” “I want to have a positive impact on others,” and “It is important to me to do good for others through my work.” Reliability of the scale was α = 0.94.

Enacted Incivility (Afternoon, t and t + 1)

We measured enacted incivility with three items adapted from Rosen et al. (2016). The items were: “Today, I put one or more coworkers down or acted condescendingly toward them,” “Today, I paid little attention to one or more coworkers’ statements or showed little interest in their opinion,” and “Today, I ignored or excluded one or more coworkers from professional camaraderie.” Average reliability across study days was α = 0.70 (t + 1 α = 0.70).

Guilt (Evening, t)

We measured guilt with four items from Marschall and colleagues (1994). We asked participants to report how guilty they were feeling at the moment. The items were: “I felt bad,” “I felt tension,” “I felt regret,” and “I felt guilty.” Average reliability across study days was α = 0.82.

Venting (Evening, t)

We drew on work by Ilies et al. (2011) and adapted three items to measure venting at home in the evening (e.g., sharing negative work events with one’s spouse or partner at home). Spouses rated the venting of the focal employee with the following items: “Since leaving work today, < < employee name > > wanted to tell me about the negative events that occurred at work today,” “Since leaving work today, < < employee name > > talked to me about one or more specific bad things that happened at work today,” and “Since leaving work today, < < employee name > > made sure to tell me about the negative things about work today.” Average reliability across study days was α = 0.96.

Task Performance (Afternoon, t + 1)

We measured task performance with three items from Williams and Anderson (1991). The items were: “Today, I have fulfilled responsibilities specified in my job description,” “Today, I have performed the tasks expected of me,” and “Today, I have met the formal requirements of my job.” Average reliability across study days was α = 0.97.

Control Variables

We also included several control variables to rule out alternative explanations. First, shame and guilt have been widely used in tandem in the literature, and both have been described as self-conscious and moral emotions (Lindsay-Hartz et al., 1995; Tangney & Dearing, 2003). Because incivility is a behavior that violates moral standards and is frowned upon, enacting incivility may potentially also induce feelings of shame in the individual (e.g., Tracy et al., 2007). We therefore decided to model shame as a parallel mediator to guilt. We measured shame in the evening survey with four items from Marschall et al. (1994). The items were: “Right now, I feel worthless,” “Right now, I feel humiliated,” “Right now, I feel like I am a bad person,” and “Right now, I feel small.” Average reliability across study days was α = 0.85.

We also controlled for positive and negative affect on all our Level-1 variables to reduce concerns of common method variance (e.g., Podsakoff et al., 2003). We measured both positive and negative affect in the morning survey using five items each from the short-form of the positive and negative affect schedule (MacKinnon et al., 1999). Participants reported the extent to which items reflected how they felt at the moment, with sample items including “inspired” and “excited” (positive affect, average reliability across study days was α = 0.91), as well as “upset” and “distressed” (negative affect, average reliability across study days was α = 0.77).

Finally, in line with best practices for ESM research (Gabriel et al., 2019), we also included prior measures of each endogenous construct in our model to control for autoregressive effects (e.g., Lin et al., 2016). To account for linear and cyclical variation, we also controlled for day of the study, day of the week, as well as the sine and cosine of the day of the week (Beal & Ghandour, 2011).

Analytic Approach

Due to the nested nature of our data (i.e., days nested within people), we tested our model using multilevel path analysis in Mplus 8.5 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998). All of our focal variables had considerable within-person variance (54.4% in enacted incivility; 66.9% in guilt; 74.8% in venting; 49.9% in next-day task performance; 54.2% in next-day enacted incivility), supporting our use of multilevel modelling.

First, we conducted a multi-level confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), modelling items for enacted incivility, guilt, venting, next-day task performance, next-day enacted incivility, and our control variables of shame, positive affect, and negative affect at Level-1, and the items for prosocial motivation at Level-2. Taking precedent from Scott et al. (2010), we person-mean centered Level-1 items and grand-mean centered Level-2 items. Results of the CFA indicated acceptable fit [χ2(379) = 1050.11, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.91, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.89, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.04, standardized root mean-square residual (SRMR) SRMRwithin = 0.04, SRMRbetween = 0.02].

Next, to establish discriminant validity, we used the Satorra-Bentler χ2 difference test with the Maximum-Likelihood Restricted scaled correction factors to compare our model to two alternative models (Satorra & Bentler, 2001). We tested a model where the items for guilt and shame loaded onto a single construct and all other items were loaded on their respective factors. Fit indices for this model were χ2(386) = 1176.17, CFI = 0.89, TLI = 0.87, RMSEA = 0.04, SRMRwithin = 0.05, SRMRbetween = 0.02. We also tested a model collapsing next-day incivility and next-day performance onto one factor, while all other items loaded on their respective factors. The fit indices for this model were χ2(386) = 1079.70, CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.04, SRMRwithin = 0.05, SRMRbetween = 0.02. Results indicated that our proposed model fit the data significantly better than these alternative models (alternative Model 1: ∆ χ2 = 56.40, ∆df = 7, p < 0.001, alternative Model 2: ∆ χ2 = 21.72, ∆df = 7, p = 0.003).

In our multilevel analyses, we person-mean centered Level-1 predictors to remove variance attributable to between-person factors (e.g., demographics and other individual differences), and we grand-mean centered our Level-2 prosocial motivation variable to facilitate interpretation of cross-level results (Enders & Tofighi, 2007). In addition, we modeled hypothesized slopes at Level-1 as random and control paths as fixed for model parsimony (e.g., Wang et al., 2013). To analyze multilevel mediation and moderated mediation effects, we adapted the procedure proposed by Preacher et al. (2010) and used a Monte Carlo bootstrap with 20,000 simulations to calculate 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals around indirect and conditional indirect effects (e.g., Gabriel et al., 2021). Furthermore, we estimated conditional indirect effects at 1 standard deviation (SD) above and below the mean of prosocial motivation. Finally, following common practice for such analyses (e.g., Jennings et al., 2022), missing data were handled using the default full information maximum likelihood estimator in Mplus.

Study 1: Results

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for within-person and between-person study variables are presented in Table 1. Results of the simultaneous multilevel path analysis are provided in Tables 2 and 3 summarizes the indirect and conditional indirect effects.

To align with our theoretical framework and to ensure that we had time separation when testing our hypotheses, we modeled the effects of enacted incivility measured in the afternoon on day t on guilt measured in the evening on day t. Next, we modeled the effects of these two variables on same-day venting behaviors (measured in the evening at home by one’s spouse), next-day performance (measured the next day in the afternoon at work), and next-day enacted incivility (measured the next day in the afternoon at work). In all analyses, we controlled for previous-day measures of endogenous variables, and therefore our results reflect changes in these outcome variables (Scott & Barnes, 2011).

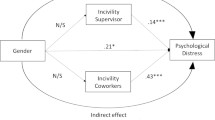

Hypothesis 1 proposed that enacting incivility at work would lead to increased feelings of guilt. Results showed that enacting incivility in the afternoon positively and significantly related to guilt measured in the evening (γ = 0.09, SE = 0.04, p = 0.024), providing support for Hypothesis 1. Hypothesis 2 proposed that the positive effect of enacted incivility on guilt would be stronger for employees higher (vs. lower) in prosocial motivation. As shown in Table 2, the cross-level effect of prosocial motivation was significant (γ = 0.16, SE = 0.07, p = 0.012), and the pattern of this effect is shown in Fig. 2. In support of Hypothesis 2, simple slope analyses revealed that the relationship between enacted incivility and guilt was positive and significant for individuals with higher levels of prosocial motivation (+ 1 SD; γ = 0.20, SE = 0.08, p = 0.011), but not significant for individuals with lower levels (− 1 SD; γ = − 0.01, SE = 0.03, p = 0.666).Footnote 7

Study 1: moderation effect of prosocial motivation on the relationship between enacted incivility and guilt. Cross-level moderating effect of prosocial motivation on the within-person relationship between enacted incivility and guilt. Simple slopes reveal that the relationship between enacted incivility (rated by employees in the afternoon of day t) and guilt (rated by employees in the evening of day t) was significant and positive at higher levels of prosocial motivation (γ = 0.20, SE = 0.08, p = 0.01), but not at lower levels of prosocial motivation (γ = − 0.01, SE = 0.03, p = 0.67)

Hypothesis 3 proposed that enacting incivility at work would be associated with increased venting at home via feelings of guilt. Results showed that the relationship between guilt and venting at home that evening was positive and significant (γ = 0.45, SE = 0.12, p < 0.001), as was the indirect effect of enacted incivility to venting at home via guilt (estimate = 0.042; 95% CI [0.0080, 0.0988]), providing support for Hypothesis 3 (please see Table 3).Footnote 8

Hypothesis 4 posited that enacting incivility would lead to increased next-day task performance via guilt. We found that feelings of guilt in the evening were positively and significantly related to task performance the next day (γ = 0.15, SE = 0.07, p = 0.029). In addition, there was a positive and significant indirect effect of enacted incivility (day t) on employees’ next-day task performance (day t + 1) via increased feelings of guilt (day t) (estimate = 0.014; 95% CI [0.0010, 0.0391]), providing support for Hypothesis 4.

Hypothesis 5 proposed that enacted incivility would reduce next-day enacted incivility via guilt. Results supported Hypothesis 5, as guilt in the evening was negatively and significantly related to enacted incivility the next day (γ = − 0.06, SE = 0.03. p = 0.029), and the indirect effect of enacted incivility (day t) on next-day enacted incivility (day t + 1) via guilt (day t) was also negative and significant (estimate = − 0.005; 95% CI [− 0.0155, − 0.0005]).Footnote 9

As previously mentioned, we also analyzed shame as a parallel mediator to guilt to rule out the possibility that incivility might lead to downstream outcomes via shame instead of guilt. Results indicated that the relationship between enacting incivility in the afternoon and shame measured in the evening was not significant (γ = 0.08, SE = 0.05, p = 0.128). This non-significant result may be because shame is an intense emotion that arises in response to failures associated with unchangeable aspects about the self, compared to guilt, which is often elicited by a specific behavior (Tracy et al., 2007). Thus, because incivility varies in response to daily experiences (e.g., Rosen et al., 2016), it may lead to feelings of guilt compared to feelings of shame. In addition, results indicated that shame was not significantly related to either venting at home (γ = 0.05, SE = 0.20, p = 0.823), next-day task performance (γ = − 0.07, SE = 0.10, p = 0.448), or next-day incivility (γ = 0.11, SE = 0.09, p = 0.232), ruling it out as an alternative explanation for the downstream effects of guilt.

Although not hypothesized, we also estimated the conditional indirect effects of enacted incivility on dependent variables at higher and lower (+ / − 1 SD) levels of prosocial motivation (please see Table 3). Furthermore, to observe the practical relevance of our model, we calculated variance explained using the formula provided by Bryk and Raudenbush (1992). Our model explained 3% of the variance in guilt, 12% of the variance in venting, 2% of the variance in next-day performance, and 2% of the variance in next-day enacted incivility.

Study 1 Discussion

Study 1 utilized an ESM with employees in a working setting to capture the daily nature of enacted incivility (e.g., Cortina et al., 2017; Schilpzand et al., 2016; Woolum et al., 2024). Our results suggest that employees are likely to experience guilt after enacting incivility, and prosocially-motivated individuals tend to experience higher levels of guilt following such behavior (Hypotheses 1 and 2). In addition, the consequences of incivility-induced guilt are likely to manifest in increased venting at home in the evening, as well as more reparative behaviors the next day at work, in the form of increased task performance and reduced incivility (Hypotheses 3–5). Study 1 has several strengths, as we examined our full model using a daily study while also controlling for several confounding variables and alternative explanations such as shame, positive and negative affect, and cyclical effects. That said, Study 1 has a few limitations. First, although we control for previous day lags of endogenous variables, we are unable to establish the causality of our effects. Second, given that we measure enacted incivility, we are unable to examine the characteristics of the incivility event, which may provide more insight into the implications of such behavior. We address these limitations across two experimental studies (Studies 2a and 2b), where we adopt a recall paradigm to examine the specific nature of the incivility incident and strengthen the internal validity of our findings.

Study 2a: Method

Participants

We recruited 163 participants on Prolific, an online platform for academic research, offering $4 for a 30-min survey (University of Florida IRB 202002477: “Experimental Study of Perceptions in the Workplace). To be eligible, participants needed to be 18 years or older and work full-time in the United States (we excluded self-employed individuals). We included three attention checks to ensure that participants were focused and their responses were reliable, and as a result, we excluded 16 individuals who failed these attention checks from analyses. In addition, we utilized a written manipulation for this study (described in detail below), and ran a response quality check to ensure that responses adhered to instructions, consequently removing 8 additional individuals who did not follow instructions.Footnote 10 Our final sample consisted of 139 individuals (66 in the enacted incivility condition and 73 in the control condition), the majority of whom were male (57.6%). The average age of participants was 36.9 years (SD = 9.6), average full-time work experience was 14.7 years (SD = 9.1), and most participants held at least a Bachelor’s degree (77.0%).

Procedure

To manipulate incivility, we relied on methods developed in prior incivility research (Diefendorff & Croyle, 2008; Porath & Pearson, 2012). We randomly assigned participants to an enacted incivility condition or to a control condition. In the enacted incivility condition, we instructed participants to recall an incident in which they acted with incivility toward a coworker, and to write four to six sentences detailing that interaction. We provided participants in this condition with a brief description (“uncivil, rude, or disrespectful to a coworker”) and examples of incivility.Footnote 11Footnote 12 In the control condition, we instructed participants to recall and write four to six sentences describing a general interaction with a coworker at work. We relied on writing tasks because recalling details associated with a specific incident helps increase recall accuracy and vividness (Lang et al., 1980; Robinson & Clore, 2001), and recall methods have been utilized widely in past research (Lin et al., 2019; Mitchell et al., 2015).Footnote 13

Measures

Incivility Intervention

We dummy coded the incivility intervention such that the enacted incivility condition took a value of 1 and the control condition took a value of 0.

Guilt

We measured guilt with the same four items from Marschall and colleagues (1994) as in Study 1. Participants were asked to reflect on how guilty they felt following the experience that they had just described (enacted incivility or control). Reliability of the scale was α = 0.88.

Prosocial Motivation

Same as in Study 1, we measured prosocial motivation using the four items developed by Grant (2008). Reliability of the scale was α = 0.94.

Study 2a: Results and Discussion

The means, standard deviations, and correlations of study variables are shown in Table 4. We first conducted a CFA, in which we modelled the items for guilt and prosocial motivation on their respective factors. Results of the CFA indicated acceptable fit (χ2(19) = 23.16, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.04, SRMR = 0.03).

To test the effect of enacted incivility on subsequent guilt, we conducted a one-way ANOVA with condition as the factor variable, and found the guilt levels in the two conditions to be significantly different from each other (F(1, 137) = 97.59, p < 0.001). Supporting Hypothesis 1, results showed that those in the enacted incivility condition experienced significantly more guilt (M = 2.91, SD = 1.07) compared to participants in the control condition (M = 1.42, SD = 0.66).

To test Hypothesis 2, we ran a regression analysis to examine whether the effect of enacted incivility on guilt was stronger for those who were higher (vs. lower) in prosocial motivation. In the regression, we entered the manipulation variable (1 = enacted incivility; 0 = control) and the prosocial motivation variable (both of which were mean centered, but results remain the same if they are entered uncentered), as well as the interaction term of these two centered variables. As shown in Table 5, the moderating effect of prosocial motivation on the relationship between enacted incivility and guilt was positive and significant (B = 0.39, SE = 0.17, p = 0.019). To help interpretability, we graphed the interaction at higher (+ 1 SD) and lower (− 1 SD) levels of prosocial motivation (Cohen et al., 2013), as shown in Fig. 3. In addition, following Preacher and colleagues (2006), we examined simple slopes at higher (+ 1 SD) and lower (− 1 SD) levels of prosocial motivation. Supporting Hypothesis 2, the association between the intervention and subsequent guilt was stronger for those who were higher (B = 1.79, SE = 0.21, p < 0.001) versus lower (B = 1.08, SE = 0.21, p < 0.001) on prosocial motivation.Footnote 14Footnote 15

Study 2a Discussion

As in Study 1, we found that enacted incivility was associated with feelings of guilt, and this effect was heightened for prosocially-motivated individuals. A strength of Study 2a is that enacted incivility is experimentally manipulated. However, it is possible that perpetrators of incivility may feel justified in enacting such behavior, which may moderate the extent to which they feel guilty following the incident. Indeed, McGraw (1987) posited that individuals may experience less guilt when their interpersonal transgressions are intentional, as opposed to accidental. Thus, to address this research question, we conducted a second experimental study in which we re-tested our first two hypotheses, and examined feelings of justification as a potential factor that may determine the extent to which perpetrators of incivility feel guilty.

Study 2b: Method

Participants

We recruited 300 participants on Prolific and offered $2 for a 7-min survey (University of Florida IRB ET00022199: “Workplace Interactions”). Participants were required to be 18 years or older and work full-time in the United States (we excluded self-employed individuals). Following the same process as in Study 2a, we removed 12 participants who failed attention checks, and 23 participants who did not adhere to instructions. Our final sample consisted of 265 individuals (119 in the enacted incivility condition and 146 in the control condition), the majority of whom were male (53.6%) and Caucasian (67.9%; 13.6% Asian, 8.3% Black/African American, 6.0% Hispanic, 4.2% multi-racial). The average age of participants was 39.2 years (SD = 11.7), average organizational tenure was 7.2 years (SD = 6.6), and the majority held at least a Bachelor’s degree (81.1%). Participants worked in a variety of industries, such as manufacturing, hospitality, construction, and retail services.

Procedure

Similarly to Study 2a, we randomly assigned participants to an enacted incivility condition or to a control condition.Footnote 16 To account for the possibility that participants may be inclined to recall and write about a severe incivility incident, we revised our manipulation instructions used in Study 2a and asked participants to write about the most recent instance of enacted incivility. We similarly asked participants in the control condition to recall and write about the most recent interaction they had with a coworker. To ensure that our incivility intervention had the intended effect, we included an explicit manipulation check after the intervention. Participants rated the extent to which they engaged in uncivil behaviors in the event described using the three-item scale adapted from Rosen et al. (2016) that we used in Study 1 to capture incivility. A sample item was “In the event described above, I put one or more coworkers down or acted condescendingly toward them” (α = 0.83). We ran a one-way ANOVA in SPSS with the intervention condition as the factor and the incivility measure as the dependent variable. Results showed that there were significant differences across conditions (MIncivility = 3.15, SDIncivility = 0.98; MControl = 1.29, SDControl = 0.65; F(1, 263) = 343.73, p < 0.001), providing support for the efficacy of our incivility intervention.

Measures

Incivility Intervention

As in Study 2a, we dummy coded the incivility intervention such that the enacted incivility condition took a value of 1 and the control condition took a value of 0.

Guilt

As in Study 1 and Study 2a, we measured guilt with four items from Marschall and colleagues (1994). Reliability of the scale was α = 0.89.

Prosocial Motivation

As in Study 1 and Study 2a, we measured prosocial motivation with four items developed by Grant (2008). Reliability of the scale was α = 0.96.

Study 2b: Results

The means, standard deviations, and correlations of study variables are shown in Table 6. Similar to Study 2a, we first conducted a CFA in which we modelled the items for guilt and prosocial motivation on their respective factors. Results indicated acceptable fit (χ2(19) = 50.55, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.03).

To test Hypothesis 1, we conducted a one-way ANOVA with the condition as the factor variable, and results indicated that there was a significant difference in reported feelings of guilt (F(1, 263) = 98.46, p < 0.001). Supporting Hypothesis 1, results showed that those in the enacted incivility condition experienced significantly more guilt (M = 2.53, SD = 1.13) compared to participants in the control condition (M = 1.40, SD = 0.71).

In testing Hypothesis 2, we ran a regression analysis in which we entered the manipulation variable (1 = enacted incivility; 0 = control) and the prosocial motivation variable (both of which were mean centered; results remain the same if they are entered uncentered), as well as the interaction term of the two centered variables. As indicated in Table 7, results showed that the moderating effect of prosocial motivation on the relationship between enacted incivility and guilt was non-significant (B = 0.12, SE = 0.11, p = 0.294), in contrast to what we found in Study 1 and Study 2a.Footnote 17Footnote 18

Another purpose of Study 2b was to investigate whether feelings of justification moderated the association between enacted incivility and subsequent guilt. To test this research question, after participants described their uncivil behavior, we asked them to discuss whether they felt justified for their behaviors and why they felt this way. We then coded their responses to create a dummy variable for justification (1 = justified; 0 = non-justified) and ran a one-way ANOVA for only the responses in the incivility condition (given that justification only applies to the participants who wrote about their uncivil behavior) in which the justification dummy variable was the factor variable and guilt was the dependent variable. As expected, results indicated that there was a significant difference between the two conditions (F(1, 117) = 32.01, p < 0.001), such that those who felt justified for their behavior experienced significantly less guilt (M = 2.21, SD = 1.01) compared to participants who did not feel justified (M = 3.39, SD = 1.01). Thus, although enacted incivility may result in higher feelings of guilt on average (given that those in the enacted incivility condition experienced more guilt compared to the control condition), of those who do enact incivility, feelings of guilt may be attenuated when they feel more justified for their behavior.

General Discussion

Much of the research on workplace incivility has focused on understanding the negative effects of incivility on victims and observers, with little work examining how enacting incivility may influence the perpetrators themselves. We contribute to the recent stream of research that explores the implications of negative work behaviors for actors (e.g., Foulk et al., 2018; Liao et al., 2018; Yuan et al., 2018) by studying the complex affective and behavioral outcomes associated with acting with incivility at work. Across three studies, we show that employees who acted with incivility experienced more guilt, and that this effect was generally stronger for those who were higher (vs. lower) in prosocial motivation. In Study 1, we also found evidence that incivility-induced guilt was associated with increased venting toward one’s spouse in the evening at home as well as increased performance and decreased incivility the next day at work.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

Our work offers several theoretical and practical contributions. First, we contribute to the incivility literature by taking an actor-centric approach to understanding how incivility may impact perpetrators. Our findings indicate that although incivility may be low in intensity and characterized by ambiguous intent to harm (Pearson et al., 2005), it can lead to complex outcomes for the perpetrator driven by guilt. Thus, seemingly innocuous acts like incivility may not only harm others, as shown in previous research (Bowling & Beehr, 2006; Porath & Erez, 2009; Porath & Pearson, 2013), but may also significantly impact the subsequent emotions and behaviors of perpetrators, as shown here.

Second, and relatedly, we contribute to the incivility literature by considering its complex burdensome as well as reparative implications that manifest via guilt and span different social domains. Our work shows that in the home environment, guilty perpetrators of incivility vent toward their partners. This may happen because the home environment feels more comfortable and safer to get things off one’s chest, even though venting may be burdensome to partners (e.g., Rosen et al., 2021). At the same time, our findings also show that, at work, guilty perpetrators are likely to engage in reparative efforts (Baumeister et al., 1994, 1995; Ilies et al., 2013), as captured by reduced subsequent incivility and increased task performance. These behaviors may occur as guilty perpetrators try to uphold salient norms in the work environment following their uncivil behavior. Our consideration of outcomes across two domains—home and work—adds to the incivility literature by suggesting that rude events that happen at work may have implications for social domains outside of work.

Third, our findings provide insight into the affect literature. Although most of the research has viewed emotions as an outcome and response to external stimuli (e.g., Spector & Fox, 2002; Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996), our use of the behavioral concordance model suggest that trait-discordant behavior can also influence individuals’ affective states. This agentic approach to affect can open doors to research focused not only on the affective consequences of environmental experiences (such as acts of incivility), but also on outcomes that very depending on how individuals respond to these experiences.

Our findings have several practical implications for employees and their organizations as well. First, since incivility has negative consequences not only for recipients but also for perpetrators and their spouses, we recommend that companies and managers work hard to reduce incivility at work. The broader management literature suggests that interventions that ask employees to recall instances in which they enacted prosocial acts or asked to take others’ perspectives at work reduce their chances of mistreating others at work (Song et al., 2018). Existing research, therefore, suggests that such interventions may alleviate some of the negative effects of incivility that we see here.

Second, our daily study (Study 1) suggests that incivility may manifest on any given day for many individuals at work (e.g., Hülsheger et al., 2021; Rosen et al., 2016). Accordingly, organizations may want to provide employees with daily resources such as opportunities for breaks, access to nature, and positive affirmations because research suggests that these help individuals regulate and manage negative behaviors from day to day (e.g., Meier & Gross, 2015; Rosen et al., 2016). Organizations that have high-stress cultures or high workloads may be particularly susceptible to incivility resulting from an inability to regulate such behavior and may benefit the most from such interventions.

A third practical implication of our work is that if employees are rude on a particular day at work for reasons that feel outside their control (e.g., sleep deprivation due to having an infant), they can take solace in knowing that their guilt may have self-correcting effects across workdays, as captured by next-day improved task performance and reduced incivility. Although we find reparative effects for incivility-induced guilt, we are quick to add that these effects do not justify the enactment of incivility at work. Indeed, not only are there counter-balancing consequences for the perpetrator as we find here (feelings of guilt and increased venting), but as prior research has shown, incivility tends to have pervasive detrimental effects on others at work as well (Bowling & Beehr, 2006; Porath & Pearson, 2013). Thus, while it is good to know that employees could alleviate the consequences of their incivility to some extent (at least at work), the negatives of incivility seem to far outweigh the positives, supporting our call to reduce incivility in organizations.

A final practical implication concerns individuals who are prosocially-motivated. In two of our studies, we found that prosocially-motivated individuals experienced more guilt after enacting incivility. Such individuals should be aware that enacting negative behaviors that go against their dominant social motives may affect them more than others. Given the wide-ranging positive effects of hiring and retaining employees high in prosocial motivation (e.g., Bolino & Grant, 2016; Liao et al., 2022), it may be worthwhile for managers and organizations to help these employees to avoid incivility or to better cope with the guilt that ensues by providing opportunities to realign their behaviors with their prosocial tendencies.

Limitations and Future Research

Our findings should be taken in light of the limitations of our studies. First, with the exception of enacted incivility in Study 2a and Study 2b, which was manipulated, and venting, which was reported by spouses in Study 1, all other measures across all studies were self-reported, which raises concerns of common method bias and source (Podsakoff et al., 2003). On the one hand, the focal individual is the best person to rate their feelings of guilt and to report on enacted incivility, as others may not be able to accurately observe these experiences on a daily basis (e.g., Gabriel et al., 2018; McClean et al., 2021). On the other hand, when employees feel guilty for engaging in uncivil behaviors on a given day, it is possible that they may report on their task performance and reduced incivility more positively on subsequent days to compensate for their previous negative behavior.

We tried to mitigate concerns of common method bias and source in Study 1 in several ways. First, we person-mean center our within-person predictors and controls to remove between-person variance and thus minimize concerns of person-level factors—such as social desirability and response biases—impacting our results (Beal, 2015). Second, we controlled for state affect to ensure that our responses were not due to other affective states (Gabriel et al., 2019). Third, to reduce concerns of reverse causality, we controlled for the lagged measure of each focal outcome, which also helps in interpreting our effects as showing change over time (Scott & Barnes, 2011). Fourth, we controlled for cyclical variations during the week and during the study period that may have influenced our associations (Beal, 2015). Fifth, our measures were separated in time, reducing concerns of common method bias and source (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Nonetheless, to more directly address concerns of common method bias and source, we invite future research to utilize other-reported measures of task performance and incivility.

Although we followed the footsteps of previous research in utilizing the Williams and Anderson (1991) items to capture task performance (e.g., Fu et al., 2021; Rosen et al., 2020), self-reported measures of task-performance have limitations, and future research should try to replicate our findings with more objective measures. Also, given that job performance consists of multiple factors (Carpini et al., 2017; Griffin et al., 2007), we invite future research to examine whether incivility-induced guilt may have differential effects on specific forms of performance (proficiency vs. adaptivity vs. proactivity) as well as on different levels of performance behaviors (individual vs. team vs. organizational).

In Studies 2a and 2b we manipulated incivility using a recall task, which may have limitations. Recall studies represent a strong situation and our guilt outcome may have been influenced by demand characteristics. However, given that we were able to replicate effects across three studies utilizing different methods, we are confident of the robustness of our findings despite the potential effects of demand characteristics. Furthermore, although recall studies have their limitations, they can be helpful when replicating effects in conjunction with other primary studies (e.g., Gloor et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2019), and have been used in previous incivility research as well (Porath & Pearson, 2012). That said, we invite future research to consider alternative approaches to manipulating incivility.

We examined the next-day implications of incivility-induced guilt, but future research may provide additional insight into the temporal dynamics surrounding the implications of enacted incivility. For example, it is possible that perpetrators of incivility may initially feel justified and only experience guilt several days later, while another possibility is that perpetrators may initially reduce their uncivil behaviors in response to feelings of guilt but re-engage in such behavior on subsequent days once the effects of guilt ‘wear off.’ Thus, it may be interesting for future research to examine the long-term effects of incivility-induced guilt as well as when and for whom these effects may differ.

We explored the moderating effects of feeling justified for the consequences of enacting incivility in Study 2b, but other characteristics of each incivility incident—such as its severity or its significance—may also influence the subsequent guilt that the focal individual may experience following incivility. In addition, it is possible that the implications of enacting incivility toward a single coworker versus multiple coworkers may differ. We encourage future research to examine the different characteristics of incivility incidents and parse out the effects that they may have for the perpetrator.

Future research may also want to examine additional outcomes associated with guilt following one’s uncivil behaviors. For example, individuals may seek to manage their burdensome feelings of guilt at home via withdrawal or spousal support seeking, while they may also experience next-day psychological withdrawal and turnover intentions. Additionally, when examining the implications of incivility-induced guilt, future research may seek to control for other negative experiences at work that may contribute to these outcomes. For example, individuals may engage in venting behaviors at home due to other events that precede or follow the incivility event.

In contrast to Study 1 and 2a where prosocial motivation moderated the association between enacted incivility and guilt, in Study 2b we did not find a significant moderation effect for prosocial motivation. This discrepancy may be due to sampling error, and we invite future research to replicate and extend our findings in new settings, with new samples, and with different study designs. In addition, other person-level characteristics may also play a moderating role in the association between incivility and guilt. For example, certain traits may weaken the association between incivility and guilt because some people (perhaps narcissistic or disagreeable people) may not necessarily be aware of the counter-normative nature of incivility. Relatedly, given that different industries and organizations may hold differing workplace norms, varying civility norms across organizations and industries may also moderate the extent to which employees experience guilt following enacted incivility. Finally, although we examined moderating factors for the path from enacted incivility to guilt, future research may consider additional situational and personal factors that elicit more burdensome or more reparative behavioral outcomes in response to feelings of incivility-induced guilt.

Conclusion

Taking an actor-centric perspective, we document the emotional and behavioral consequences of acting with incivility at work. We find that enacted incivility is guilt-inducing, subsequently leading to complex behaviors. At home, incivility-induced guilt is associated with more venting toward one’s spouse, whereas at work it is associated with higher task performance and less incivility the next day. These effects seem to be more pronounced for prosocially-motivated employees. We are hopeful that our study will motivate more actor-centric research on incivility.

Notes

Although used in tandem with similar self-conscious emotions such as regret and shame (Breugelmans et al., 2014; Lindsay-Hartz et al., 1995; Tangney & Dearing, 2003), guilt is uniquely relevant in the context of enacted incivility. Guilt captures feelings of distress resulting from interpersonal harm (e.g., My behavior caused harm to others), whereas regret captures broader emotions that encompasses both interpersonal as well as intrapersonal harm (e.g., My behavior caused harm to myself; Breugelmans et al., 2014). In addition, whereas guilt is a behavior-specific emotion (e.g., I committed a bad behavior), and is therefore more relevant in the context of daily incivility, shame is a person-specific emotion that captures reflections of unchangeable aspects of the self (e.g., I am a bad person) (Baumeister et al., 1994; Tangney & Dearing, 2003; Tracy et al., 2007). Thus, given that incivility is conceptualized as a behavior that fluctuates from day-to-day as opposed to an enduring tendency (e.g., Rosen et al., 2016), reflections on such behaviors may be more likely to elicit feelings of guilt rather than shame.

Across all studies we used two-tailed tests to examine our hypotheses.

Data reported in this study were collected as part of a larger data-collection effort. No variables in this model overlap with variables in any other manuscript. Please refer to Appendix A for a data transparency table that outlines the additional variables we measured as a part of this data collection effort.

In our final sample, most participants were recruited from either University A (77) or University B (13). The remaining participants (17) worked at various companies in the area.

Participants in our study could earn up to $70. Completion of the initial signup survey was worth $5. From there, as this was part of a larger data collection effort, participants completed 3 surveys per day for 15 days (45 total surveys). We paid participants $1 for each of the first 25 surveys they completed and $2 for each of the next 20 surveys. As participants were paid on a per-survey basis, they could cease participating in the study at any time and still receive payment for the surveys they completed to that point. Participants were paid via an Amazon gift card based on the number of surveys completed.

In response to an anonymous reviewer’s comment, we examined whether our findings were robust when accounting for gender. To do so, in Study 1, we first controlled for gender’s main effects on our outcomes at the between-person level, and results indicated that our hypothesized results remained consistent. We then tested a model in which we examined gender as a moderator of the relationship between enacted incivility and guilt as well as the relationship between guilt and downstream behaviors to examine whether these effects may differ based on gender. We found that gender moderated the relationship between enacted incivility and guilt (γ = 0.18, SE = 0.09, p = 0.036), such that this relationship was positive and significant for females (γ = 0.14, SE = 0.05, p = 0.002), but non-significant for males (γ = − 0.04, SE = 0.07, p = 0.528). In addition, in examining gender as a second-stage moderator of the relationship between guilt and downstream behavioral outcomes, we found that gender moderated the relationship between guilt and venting at home (γ = 0.60, SE = 0.16, p < 0.001), such that the positive relationship between guilt and venting at home was positive and significant for females (γ = 0.56, SE = 0.13, p < 0.001) but non-significant for males (γ = − 0.04, SE = 0.13, p = 0.777). However, gender did not moderate the relationship between guilt and subsequent performance at work (γ = − 0.22, SE = 0.25, p = 0.378), nor the relationship between guilt and subsequent enacted incivility at work (γ = − 0.08, SE = 0.08, p = 0.354). That said, given that this sample is skewed female (79% of the sample is female), these gender effects may be sample-specific. In fact, we did not find gender effects in our more gender balanced Studies 2a and 2b. We invite future research to examine gender as a potential moderator for the effects we find in our studies with larger and more representative samples.

Although we modelled venting as a parallel outcome to next-day performance and next-day incivility based on theoretical arguments surrounding the complex (both burdensome and reparative) nature of incivility-induced guilt (Baumeister et al., 1994), an anonymous reviewer asked whether venting may also be a sequential mediator linking feelings of guilt with reparative behaviors the next-day at work. Accordingly, we further test and discuss this possibility in Appendix B.

An anonymous reviewer asked whether perpetrators of incivility may reduce incivility the next day as a result of guilt, but then revert back to their pattern of uncivil behaviors the day after. To test for this possibility, we ran a model in which we also regressed enacted incivility from day t + 2 on guilt and incivility measured on the focal day (e.g., Wang et al., 2013). Results indicated that these reparatory effects were found to be more short-lived, as the relationship between day t guilt and day t + 2 incivility was non-significant (γ = 0.003, SE = 0.03, p = 0.924), as was the indirect effect of day t incivility on day t + 2 incivility via day t guilt (estimate = 0.000; 95% CI [− 0.0181, 0.0203]).

Five individuals stated that they had never enacted incivility at work, and an additional three provided responses that were not related to an incident in which they had enacted incivility.

We provided participants with the following examples: “e.g., you put this person down or acted condescendingly toward him/her, paid little attention to his/her statements or showed little interest in his/her opinion, and/or ignored or excluded him/her from professional camaraderie”.

Sample written responses from the incivility condition are listed in Appendix C.

We conducted a post-hoc manipulation check following the procedures outlined in Foulk et al. (2018). We randomly selected 50 responses from each condition (incivility and control) and recruited two independent coders who were unaware of the study purpose and the manipulation conditions. Raters read each response and responded to the question “To what extent is this person describing an instance in which they were uncivil, rude, or disrespectful toward someone else?” The scale ranged from 1 = “None at All” to 5 = “A Great Deal,” and results revealed good agreement between raters (ICC[1] = 0.85, ICC[2] = 0.92; LeBreton & Senter, 2008). Therefore, we aggregated their ratings to form a single variable and ran a one-way ANOVA with the study condition as the factor. These analyses showed that responses in the incivility condition were rated as being significantly more reflective of incivility than responses in the control condition (MIncivility = 3.11, SDIncivility = 1.03; Mcontrol = 1.06, SDcontrol = 0.16; F(1, 98) = 192.58, p < 0.001), suggesting that the manipulation had the intended effect.