Abstract

This study aims to investigate situational (emotions) and individual factors (peace attitude and personality) on decision making, by using the prisoner’s dilemma paradigm. The study involved 104 participants. The positive, neutral and negative emotional states were induced by watching a video. The prisoner’s dilemma tasks were administered immediately after the video. Participants were divided into two groups, one with high and one with low levels of peace attitude, and an analysis of repeated measures of variance was subsequently applied. Results show how situational factors, such as exposure to positive rather than negative emotions, increase cooperative rather than competitive choice. For the individual factor of the peace attitude results showed that peaceful people prefer cooperation. This study suggests that both situational factors (emotions) and individual factors (attitude to peace) influence cooperative decision-making choices. Future research should further evaluate the role of situational and individual factors together and their interactions. This work seems to suggest that to achieve a more peaceful society interventions should be made involving both situational and individual factors. With reference to individual factors, learnt behaviors including the peace attitude has to become so automatized that it can overcame any negative emotions induced by the setting. Understanding the developmental pathways that can influence individual factors to consistently choose peace is important so as to promote a stable culture of peace across several levels of observation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The study of decision-making processes was initially an object of interest in economic research and above all in the processes of rational choice that involve individual and collective actors. It has been suggested that decision-making in social dilemmas relies on three factors: the evaluation of a choice option, the relative judgment of two or more choice alternatives, and situational factors affecting the ease with which judgments and decisions are made (Kuzmicheva, 2020; Proto et al., 2020).

Recent literature has focused on analysis of the factors that influence the decision-making process in situations of uncertainty where the choice of an interaction strategy is required, such as in the prisoner’s dilemma (PD) game (Kuzmicheva, 2020; Proto et al., 2020; Soutschek & Schubert, 2015).

The study of PD stems from game theory, which describes how people pilot strategic interactions while aiming to optimize or maximize their interests by selecting options that provide the greatest personal utility (Thompson et al., 2021). In the PD game, there are two choice options, defect or cooperate with the coplayer or the opponent. A player’s behaviour may not follow the general model of rational behaviour (Koch et al., 2020). This can be well explained through the theory proposed by Kahneman and Tversky (1979), according to which the value of the gain or loss may be perceived differently by the players, depending on the effect of the context.

Prisoner’s dilemma (PD) paradigms

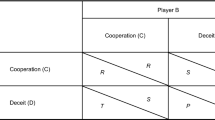

In the Prisoner’s Dilemma, two individuals, player A and player B, who cannot communicate, simultaneously choose one of two strategies: cooperate (C) or defect (D). The resulting payoff or rewards depend on both players’ choices. When one cooperates and the other defects, the defector receives the largest possible reward and the co-operator receives the smallest possible reward (Stevens & Hauser, 2004; Thompson et al., 2021). When both either defect or cooperate, they will receive the same reward, although if both players defect the reward is lower than in the case that both players cooperate. Summing up, player A can maximize his outcome if he always defects and the reason is: if player B cooperates, then player A’s outcome is higher if he defects (unreciprocated defection; DC), compared to if he cooperates (mutual cooperation; CC). Importantly, also in the case that player B defects, player A’s payoff is higher if he defects (mutual defection; DD) compared to if he cooperates (unreciprocated cooperation; CD) (Soutschek & Schubert, 2015). The choice affect.

Early studies were focused on considering PD through a one-choice paradigm, with only a single choice made by each player (Floud, 1952; Roth, 1993; Tucker, 1983). Some studies have been using the iterated prisoner’s dilemma (iPD) paradigm, which differs from the original one-shot paradigm as a player can make multiple choices sequentially and learn about the opponent’s behavioural tendencies (Jeffrey & Hauser, 2004; Mienaltowski & Wichman, 2019; Proto et al., 2020; Gallotti & Grujić, 2019). Differently from the one-shot paradigm that provides for a single dominant strategy, the iPD paradigm allows the player to use adaptive strategies. They can learn about the behavioural tendencies of their counterparty and adapt their moves to the opponent's setting. One of the most used adaptive strategies is the tit for tat strategy in which each participant mimics the action of their opponent after cooperating in the first round (Montero-Porras et al., 2022).

One of the important features of the tit for tat strategy is that the coplayer cooperates on the first trial. Wing and Komorita (2002) showed that a cooperative strategy—one that initiates unilateral cooperation at the outset and then adopts a tit for tat strategy—is very effective in inducing subsequent cooperation from the other part. The effectiveness of a cooperative strategy varies directly with the cooperative orientation of the coplayer (a cooperative strategy is more effective against a cooperative than a competitive person), and initial cooperation is more effective if it is repeated more than once (Wing & Komorita, 2002).

However, the choice of a certain interaction strategy, such as cooperation and defection can be determined by a number of factors and conditions, such as situational factors for example, inducted emotional state with a movie presentation, time pressure, cognitive load, opponent’s characteristics, physical feature or social identity (Guilfoos & Kurtz, 2017; Kuzmicheva, 2020), and personal factors, for example, personality traits, cooperative and peace attitudes and cognitive processes (Fabio et al., 2022; Fabio & Towey, 2018; Malesza, 2020b; Soutschek & Schubert, 2015).

Therefore, the choice of a cooperative or competitive strategy may be the consequence of two types of factors: indivividual factors such as peace attitude, empathy and personality traits, and situational factors such as emotional settings.

Situational factors

With reference to situational factors, emotions are variables that influence decision making in PD paradigms (Lerner et al., 2019). Emotions have a fundamental role in human survival and are useful in differentiating co-operators from deserters (Frank et al., 2004). Emotional processes are therefore fundamental to understand the moods and behaviours of social partners, allowing us to hypothesize future intentions of the other and consequently regulate our own behaviours in view of objective advantages (Hareli et al., 2010). Recent literature investigated the possibility that experiencing negative emotions correlates with the implementation of defection behaviours towards the opponent (Lerner et al., 2015).

Kuzmicheva (2020) analysed the influence of emotional state, induced with a movie, and time pressure. The results demonstrated that negative emotions increase the probability of choosing a competing strategy. Another situational factor was the influence of cognitive load on the mechanisms of social cooperation. Duffy and Smith (2014) conducted a dual-task procedure in which participants had to perform a task that occupied cognitive resources while making a choice in a PD game. In one treatment, some participants were placed under a high cognitive load (given a 7 digit-span task to recall) while other participants were placed under a low cognitive load (2 digit-span task). The results show that participants with a low load behaved more strategically than participants with a high load. In fact, participants with a low load exhibited more strategic defection near the end of play than the high load participants (Duffy & Smith, 2014). Other studies (Mieth et al., 2021) do not confirm these results. Mieth et al. (2021) found no or minimal relationships between cognitive load and strategic behaviours.

Moreover, knowledge of the opponent’s strategy setting, another situational factor, can influence a player’s moves as the player has to adapt and adjust his game strategy to his opponent’s play (Soutschek & Schubert, 2015). For example, the opponent may use an unforgiving strategy, in which he cooperates until an opponent defect once, and then always defects in each interaction. For the player it will be convenient to always cooperate. On the contrary, if an opponent always defects, the player will understand that cooperation is not the most productive choice and so he will adapt his game strategy.

Individual factors

With reference to individual factors, Thomas and colleagues (2014) tested whether empathy, considered as an individual’s relative ability to understand others’ thoughts, emotions, and intentions, acts as an individual factor that alleviates conflict resolution in social decision-making. They tested this by using the iPD game in two settings. They found that high levels of empathy were related to faster response time during the decision phase. These results suggest that empathy is related to individual differences in the engagement of mentalizing in social dilemmas and that this is related to the efficiency of decision-making in social dilemmas.

Guilfoos and Kurtz (2017) tested another individual factor. They considered personality factors, and whether information about a partner’s personality traits influences the cooperative behaviour of participants in the PD game. They established that social information is used in cooperative game strategies. The findings show also that a personal trait such as emotional stability increases the probability of the cooperation strategy choice (Kuzmicheva, 2020). Another individual factor that can affect the choices in PD game is the peace attitude (Fabio et al., 2022; Anderson, 2014) that is defined as a condition in which individuals, families, groups, communities and/or nations show low levels of violence attitude and engage in mutually harmonious relationships. Examples of peace behaviors are cooperative and kind actions. More in depth, peaceful behaviors occur when individuals act to establish and maintain nonviolent, harmonious relationships with others, and previous literature has proposed several ways to define the construct of peace. Galtung (1996) differentiates between two types of peace: positive and negative peace. Negative peace describes a state where something undesirable has stopped happening, positive peace refers to the restoration of relationships, constructive resolution of conflicts and the effort to build harmonious and equitable societies. Danesh (1997) gave an influential contribute to the peace construct with the Integrative Theory of Peace (ITP). According to the ITP, peace is both a psychological, but also a social, political, ethical and spiritual state with expressions in intrapersonal, interpersonal, intergroup and international areas of human life. This theory includes four sub-theories: a psychosocial, political and moral condition; a unity-based worldview that is; the prerequisite for creating both a culture of peace and healing; and a comprehensive, integrated and lifelong process of education. According to ITP, peace can only be achieved when the human need for survival, safety and security has first been met. Another definition that helps define the construct of Peace have been provided by Anderson (2004, 2014) who defines it as a condition in which individuals, families, groups, communities and/or nations experience low levels of violence and engage in mutually harmonious. More specifically, peace can only be achieved if peace attitudes are consistently observable in eight domains: interpersonal peace, social peace, civil peace, national peace, international peace, ecological peace, and existential peace. The diversity of theoretical approaches to peace poses a challenge in terms of measurement and the proposed measures differ in terms of nature, structure and number of subdomains. Starting from this construct, Broccoli et al., (2020) developed the peace attitude scale (PAS) to produce a comprehensive tool to measure peace attitudes. As in the Anderson and Danesh’s models this scale used social, political, and environmental factors.

Although recent literature has investigated both the influence of situational and individual factors in choosing a strategy in the PD game (Canegallo et al., 2020; Duffy & Smith, 2014; Fabio et al., 2022; Frank et al., 2004; Hareli et al., 2010; Lerner et al., 2015; Soutschek & Schubert, 2015; Malesza, 2020a, b; Murphy & Kurt, 2015; Thomas, 2014; Wissing & Reinhard, 2019; Kuzmicheva, 2020), it is still unclear how these can influence decision-making in an iterated context, such as the iPD game, specifically in a tit for tat context. Furthermore, in literature (Thomas, 2014), it has been considered how individual factors, such as personality traits and empathy, can influence strategic choices in the PD game, but few works investigated if the peace attitude can influence strategic choices in the PD game (Fabio et al., 2022).

For these reasons, in this study, we considered both the influence of individual factors considering peace attitude and personality, and the influence of situational factors considering contextual factors, such as emotional state, in the tit for tat strategy of the iPD game.

Current study

The aim of this study is to contribute to studies on the influence of situational and individual factors in the decision-making process.

More in depth, we predicted that situational factors affect cooperative choices in the PD game.

Positive emotions, elicited by positive video exposure, will increase the probability of a cooperation strategy; negative emotions, elicited by negative video exposure, will increase the probability of a competing strategy; we also added a neutral video exposure, which was not intended to elicit any emotion, to measure the base-line of cooperative and competitive strategies.

With reference to personal factors, we predicted that higher levels of peace attitude will lead to a higher number of cooperative choices. Moreover, we predicted that higher levels of personal traits, such as emotional stability, will lead also to a higher number of cooperative choices.

Methods

Participants

At first, the sample consisted of 130 adults that were reduced to 104 after the evaluation of the three videos (the loss of 26 participants will be detailed in the procedure section below). They were 59 females and 45 males, between 18 and 70 years (mean = 35.66 and standard deviation = 14.34). All participants were white, spoke Italian as their first language and were recruited from three regions of Italy (Calabria, Piedmont and Veneto). Fifty-eight participants were selected through the Instagram social network. The remaining participants (46) were chosen at random from an agency employed in the Service Sector. Both recruitments include participants from three regions of Italy (Calabria, Piedmont and Veneto) with the same frequency. In this work no age and gender differences were found. All participants exhibited typical development, did not exhibit any kind of pathologies or disorders, reported no psychiatric or neurological impairment and declared no use of drugs or psychotropic substances. This aspect was clarified by asking the subjects specific questions before submitting them to the experimental design. Informed consent was obtained from participants.

Measures

The Peace Attitudes Scale (PAS) was developed by Broccoli et al., (2020) and is a 22-item self-report measure with five domains which are Sociopolitical, Personal Well-Being, Ease with Diversity, Environmental Attitude and Caring. Each domain consists of a statement and participants have to fill out their response on a seven-point Likert-type response scale (never, almost never, rarely, sometimes, often, very often and always). The Sociopolitical domain contains items such as “I think people need to dialog with one another in a harmonious way”; the individual has to choose a number ranging from 1 (“never”) to 7 (“always”). The Personal Well-Being domain contains items such as “When something is wrong, I work hard to relax and to get back to a state of well-being.” The Ease with Diversity domain contains items such as “I would be afraid if I was living in an Islamic State.” The Environmental Attitude domain contains items such as “I’d like to clean dirty public places even if it wasn’t I who soiled them.” Finally, the Caring domain contains items such as “If I came across an injured animal, I wouldn’t hesitate to take care of it.” Higher scores from this scale mean that the individual has stronger peace attitudes. The Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.93 and test and retest reliability was 0.95. The criterion validity was computed with Neff’s self-compassion scale (Neff, 2003), which was correlated with PAS (r (498) = 0.56, p < 0.001).

The Italian 10-Item Big Five Inventory (Italian BFI-10; Guido et al., 2014) is the Italian version of the BFI-10 scale, originally developed in English and German by Rammstedt and John (2007). A small-scale version of the consolidated BFI was developed to provide a personality inventory for time-constrained search settings. Previous research has shown that the BFI-10 possesses psychometric properties comparable in size and structure to those of the BFI (Caprara et al., 2000; Woods & Hampson, 2005). The scale consists of an initial statement: "I see myself as a person who…" where the subject is asked to respond to each statement that describes his personality. The BFI-10 evaluates five dimensions of personality (Agreeableness: items 2, 7; Conscientiousness: items 3, 8; Emotional stability: items 4, 9; Extroversion: items 1, 6; Openness: items 5, 10) for a total of 10 items, with a duration of administration of about one minute. It uses statements representing poles of the same dimension, intending to capture the core aspects of each Big Five dimension (e.g., for the Emotional stability dimension, it evaluates how much one ‘‘is relaxed, handles stress well’’ and ‘‘gets nervous easily’’). Participants are asked to respond on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). The value of the coefficients the Spearman – Brown coefficients were 0.50 or higher.

We used an iPD game in the present study for two reasons: (1) in a one-shot dilemma game, defection is the dominant strategy (Boone et al., 2010); and (2) people usually interact with the same person for multiple times in real life. Each of the game outcomes is associated with a different pay-off. In the present study, the subjects were playing with a preprogramed computer algorithm for 25 rounds for three sessions (with a total of 75 rounds). The algorithm strategy was designed to mimic an actual human strategy.

The algorithm used always responded to the player with the tit for tat strategy or simulated the player’s previous move. This strategy is applied when the player mimics, in the current round, the partner’s choice in the previous one. The participant was asked to imagine playing with an opponent and that their winnings depended on the other player’s move. Each player had to decide whether to cooperate or defect, and each move determined a different payoff. The explanation of the game given to each participant was as follows: Player cooperation followed by partner cooperation (CC) pays euro 20 to both player and partner; player cooperation followed by partner defection (CD) pays euro 0 to the player and euro 30 to the partner; player defection followed by partner defection (DD) pays euro 10 to both player and partner; and player defection followed by partner cooperation (DC) pays 30 euro to the player and 0 euro to the partner subjects.

Procedure

The participants took part in the study individually. Positive, negative and neutral emotional states were induced in the participants by watching a video which was administered randomly. The negative-content video watched by the study participants involved an act of bullying. The positive content video watched by the participants concerned children’s play activities. Regarding the neutral content video, participants were asked to watch a scene of a busy street.

After watching the video, each participant had to communicate what type of emotion he experienced to check that the emotion felt was congruent, for example “happiness” with positive video.

The participant was also requested to score the level of the emotion on a continuum from 0 to 10. It should be noted that before the experiment each video was evaluated by experts (emotion researchers) as corresponding to positive or negative (Fedotova & Hachaturova, 2017). Despite the use of this procedure, some participants were not able to objectively describe the emotion felt. One hundred percent of participants reported positive emotions (happiness, joy, empathy etc.) after viewing the positive video, while 94% of participants experienced negative emotions (anger, pain, etc.) after viewing the negative video. After viewing the neutral video, 80% experienced congruent emotions (boredom, indifference), while the participants (20%) who had not experienced congruent emotions, or had an emotion score level below 6, were excluded from statistical analysis (26 participants).

Subsequently, the participants were subjected to the PD game, and all the participants received identical rules for the game. After learning the rules of the game, participants were asked some questions about the game to make sure they were familiar with the rules. After being subjected to the experimental factors of video and PD game participants could relax. Later, each participant had to fill out two questionnaires: 10-Item Big Five Inventory (BFI-10) and Peace Attitudes Scale (PAS).

Between the experimental session of the video and the PD game, and the administration of the two questionnaires (BFI-10 and PAS), participants could relax for 3/5 min. During the relaxation session a nature video with audio was provided via laptop (Fig. 1).

Results

Data were analysed with reference to the above-mentioned hypothesis. Before applying the repeated measures analysis of variance, participants were divided depending on scores: they were split into two groups in order to identify the group with low levels of peace attitude (below median) and the group with high levels of peace attitude (above median) (Iacobucci et al., 2015).

Peace attitude and cooperative choices

Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations of the cooperation choices of both groups (low level of peace attitude vs high level of peace attitude) in the 3 settings (negative, neutral and positive video-exposure).

A repeated measures analysis of variance was applied: 2 (group: low level of peace attitude vs high level of peace attitude) X 3 (setting: negative, neutral and positive video-exposure).

Group factor shows significant effect, F (1, 101) = 17.382, p < 0.0001. Setting factor also shows significant effect, F (2, 202) = 4.82, p < 0.01. The interaction Group X Setting shows no significant effects. Participants with high levels of peace attitude show a higher number of cooperative choices in all three video settings. Post-hoc analysis indicates that the two groups show significant differences in positive, neutral and negative video exposure, respectively t (102) = 2.87, p < 0.001, t (102) = 2.67, p < 0.001 and t (102) = 4.37, p < 0.001.

Traits of personality and cooperative choices

By correlating the BFI-10 subscales (open mindedness, emotional stability, friendliness, energy and conscientiousness) and cooperative choices in the iPD task, we found a significant correlation between emotional stability and number of cooperative choices in the neutral setting (r (102) = 0.42, p < 0.00) and between conscientiousness and number of cooperative choices in positive, neutral and negative video exposure, respectively r (102) = 0.37, p < 0.004, r (102) = 0.38, p < 0.001 and r (102) = 0.39, p < 0.001.

Discussion

Our study examined the influence of individual factors, such as personality traits and peace attitude on decision-making, and the influence of situational factors, such as emotional state, on decision-making through the iPD game. With reference to personality factors, the results are consistent with those reported in literature, which show how the personality factor of emotional stability correlates with the number of cooperative choices in the game of the PD (Kuzmicheva, 2020; Caprì et al., 2020, 2021). To our knowledge, our study is the first one investigating the relationship between the peace attitude (Anderson, 2004, 2014) and the cooperative choices both in reference to individual and situational factors. The results showed that peaceful people are predisposed to interact positively in social interactions (Cavarra et al., 2021), preferring the cooperative rather than competitive strategy. With reference to situational factors, as found in other studies (Kuzmicheva, 2020), it emerges that positive emotional states induce a higher level of cooperative choices than negative emotional states. Moreover, the elicitation of negative emotions correlated with the strategy of defection in the PD game (Lerner et al., 2015; Kuzmicheva, 2020).

Therefore, in light of our findings, the participants who viewed the videos with positive and negative emotional content were influenced by their moods and strategic decision. It is possible that habitual response patterns may became automatic and influence results from long-term memory, and the results are influenced also by situational factors. The results of the present experiment confirm that both individual and situational factors interact and give us some directions; for example, it will be important to study under which conditions individual factors can have a strong effect on situational ones. It would also be useful, in future research, to investigate whether the impact of individual factors could lead to a metacognitive experience of error. This research in the future should include larger sample size and involve a more heterogeneous ethnic sample. Future research may use the extended version of the Big Five questionnaire to obtain a global view of analysis of the personality factors involved in the decision-making process and may also benefit from counterbalancing to reduce the possible order effects of experimental task and questionnaire administration.

Conclusion

According to the results obtained by studying how individual factors (personality traits and peace attitude) and situational factors (emotional state) influence the choice of interaction strategies in the prisoner’s dilemma game, the following conclusions can be drawn:

Situational and personal factors are correlated with interpersonal interaction strategy choice in the situation of the prisoner’s dilemma game. Personality traits, such as emotional stability and conscientiousness, are correlated with cooperation and defection strategy choice, respectively. Among personal factors, the peace attitude has been shown seems to be a variable involved in the decision-making process, and would seem to influence cooperative responses compared to competitive ones.

The possibility of arousing positive emotions increases cooperative choice in the participants. While the possibility of experiencing negative emotions increases the number of defections of participants.

Situational factors (negative and positive emotions) have a stronger influence on interpersonal interaction strategy choice in a situation of prisoner’s dilemma than personal factors.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Anderson, R. (2004). A definition of peace. Peace and conflict. Journal of Peace Psychology, 10, 28–39.

Anderson, R. T., Novak M., Economic Justice, and War and Peace (2014). Theologian and Philosopher of Liberty: Essays of Evaluation and Criticism in Honor of Michael Novak, Gregg, S (ed.). https://ssrn.com/abstract=3155456

Boone, C., Declerck, C., & Kiyonari, T. (2010). Inducing cooperative behavior among proselfs versus prosocials: The moderating role of incentives and trust. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 54, 799–824.

Broccoli, E., Canegallo, V., Santoddı`, E., Cavarra, M, Fabio, R.A. (2020). Construction, psychometric characteristics and validity of peace attitude scale. Peace and Conflict. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1108/JACPR-04-2020-0493

Canegallo, V., Broccoli, E., Cavarra, M., Santoddì, E., & Fabio, R. A. (2020). The relationship between parenting styles and peace attitudes. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 12(4), 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1108/JACPR-04-2020-0493

Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Pastorelli, C., Bandura, A., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2000). Prosocial foundations of children’s academic achievement. Psychological Science, 11, 302–306.

Caprì, T., Gugliandolo, M. C., Iannizzotto, G., Nucita, A., & Fabio, R. A. (2021). The influence of media usage on family functioning. Current Psychology, 40(6), 2644–2653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00204-1

Capri, T., Santoddi, E., & Fabio, R. A. (2020). Multi-source interference task paradigm to enhance automatic and controlled processes in ADHD. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2019.103542

Cavarra, M., Canegallo, V., Santoddì, E., Broccoli, E., & Fabio, R. A. (2021). Peace and personality: The relationship between the five-factor model’s personality traits and the Peace Attitude Scale. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 27(3), 508–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000484

Danesh, H. B. (1997). The psychology of spirituality: From divided self to integrated self. Sterling Publishers.

Duffy, S., & Smith, J. (2014). Cognitive load in the multi-player prisoner’s dilemma game: Are there brains in games? Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 51, 47–56.

Fabio, R. A., & Towey, G. E. (2018). Long-term meditation: The relationship between cognitive processes, thinking styles and mindfulness. Cognitive Processing, 19(1), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10339-017-0844-3

Fabio, R. A., D’Agnese, C., & Calabrese, C. (2022). Peace attitude and friendliness influence cooperative choices in context of uncertainty. Peace and Conflict. https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000508

Fedotova, Zh., & Hachaturova, M. (2017). Factors of organizational decision-making about the choice of interaction strategies under conditions of uncertainty. Organizational Psychology, 7(2), 102–125.

Flood, M. M. (1952). Some experimental games. Research Memorandum RM-789, RAND Corporation.

Frank, F. D., Finnegan, R. P., & Taylor, C. R. (2004). The Race for Talent: Retaining and Engaging Workers in the 21st Century. Human Resource Planning, 27, 12–25.

Gallotti, R., Grujić, J. (2019). A quantitative description of the transition between intuitive altruism and rational deliberation in iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma experiments. Scientific Reports, 9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52359-3

Galtung, J. (1996). Peace by peaceful means: Peace and conflict, development and civilization. International Peace Research Institute Oslo.

Guido, G., Peluso, A. M., Capestro, M., & Miglietta, M. (2015). An Italian version of the 10-item Big Five Inventory: An application to hedonic and utilitarian shopping values. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 135–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.053

Guilfoos, T., & Kurtz, K. J. (2017). Evaluating the role of personality trait information in social dilemmas. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 68, 119–129.

Hareli, S., & Hess, U. (2010). What emotional reactions can tell us about the nature of others: An appraisal perspective on person perception. Cognition and Emotion, 24, 128–140.

Iacobucci, D., Posavac, S., Kardes, F., Schneider, M., & Popovich, D. (2015). The median split: Robust, refined, and revived. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25, 690–704.

Jeffrey, R. S., & Hauser, M. D. (2004). Why be nice? Psychological constraints on the evaluation of cooperation. Cognitive Sciences, 8(2), 60–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2003.12.003

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263–292.

Koch, A., et al. (2020). The ABC of society: Perceived similarity in agency/socioeconomic success and conservative-progressive beliefs increases intergroup cooperation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2020.103996

Kuzmicheva, Zh. E. (2020). Personal and situational factors of decision-making under trust-distrust (The Prisoner’s Dilemma Model). Psychology Journal of the Higher School of Economics, 17(1), 118–133. https://doi.org/10.17323/1813-8918-2020-1-118-133

Lerner, J. S., Li, Y., Valdesolo, P., & Kassam, K. S. (2015). Emotion and decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 799–823.

Malesza, M. (2020a). Grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism in prisoner’s dilemma game. Personality and Situational Differences, 158, 234–255.

Malesza, M. (2020). The effects of the Triad traits in prisoner’s dilemma game. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9823-9

Mienaltowski, A., & Wichman, A. L. (2019). Older and younger adults’ interactions with friends and strangers in an iterated prisoner’s dilemma. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825585.2019.1598537

Mieth, L., Buchner, A., & Bell, R. (2021). Cognitive load decreases cooperation and moral punishmentin a Prisoner’s dilemma game with punishment option. Scientific Reports, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04217-4

Montero-Porras, E., Grujić, J., Fernández Domingos, E., & Lenaerts, T. (2022). Inferring strategies from observations in long iterated Prisoner’s dilemma experiments. Scientific Reports., 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11654-2

Murphy, R. O., & Kurt, A. (2015). Social preferences, positive expectations, and trust based cooperation. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 67, 45–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmp.2015.06.001

Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250.

Proto, E., Rustichini, A., Sofianos, A. (2020). Intelligence, Errors and Strategic Choices in the Repeated Prisoners' Dilemma CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP14349, Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3526075

Rarnmstedt, B., & John, O. P. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 203–212.

Roth, A. E. (1993). On the early history of experimental economics. Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 15(Fall), 184–209.

Soutschek, A., & Schubert, T. (2015). The importance of working memory updating in Prisoner’s Dilemma. Psychological Research, 80(2), 172–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-015-0651-3

Stevens, J. R., & Hauser, M. D. (2004). Why be nice? Psychological constraints on the evolution of cooperation. TRENDS in Cognitive Sciences, 8, 60–64.

Thomas, Z. R. (2014). Empathy as a neuropsychological heuristic in social decision-making. Social Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2014.965341

Thompson, K., Nahmias, E., Fani, N., Kvaran, T., Turner, J., Tone, E. (2021). The Prisoner’s Dilemma paradigm provides a neurobiological framework for the social decision cascade. PLoS ONE, 16(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248006

Tucker, A. (1983). The mathematics of Tucker: A sampler. The Two-Year College Mathematics Journal, 14(3), 228–232.

Wing, T. A., & Komorita, S. S. (2002). Effects of initial choices in the prisoner’s dilemma. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 15, 343–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.419

Wissing, B. G. & Reinhard, M. A. (2019). The Dark Triad and deception perceptions. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01811

Woods, S. A., & Hampson, S. E. (2005). Measuring the Big Five with single items using a bipolar response scale. European Journal of Personality, 19, 373–390. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.542

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Fabio, R.A., Romeo, V. & Calabrese, C. Individual and situational factors influence cooperative choices in the decision-making process. Curr Psychol 43, 631–638 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04348-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04348-z