Abstract

Intensive and violent intergroup conflicts that rage in different parts of the world are real. These conflicts center over disagreements focusing on contradictory goals and interests in different domains and must be addressed in conflict resolution. It is well known, however, that the disagreements could potentially be resolved if not the powerful sociopsychological barriers which fuel and maintain the conflicts. These barriers inhibit and impede progress toward peaceful settlement of the conflict. They stand as major obstacles to begin the negotiation, to continue the negotiation, to achieve an agreement, and later to engage in a process of reconciliation. These barriers are found among both leaders and society members that are involved in vicious, violent, and protracted intergroup conflicts. They pertain to the integrated operation of cognitive, emotional, and motivational processes combined with a preexisting repertoire of rigid supporting beliefs, worldviews, and emotions that result in selective, biased, and distorted information processing. This processing obstructs and inhibits the penetration of new information that can potentially contribute to facilitating progress in the peacemaking process. The chapter elaborates on the nature of the sociopsychological barriers and proposes preliminary ideas of how to overcome them. These ideas focus on the unfreezing process which eventually may lead to reduced adherence to this repertoire, which supports the conflict’s continuation and evaluation, and increased readiness to entertain beliefs that promote peacemaking.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

Intergroup conflicts are an inherent part of human relations, having on a large scale taken place continuously and constantly throughout all millennia of history. Of these, intractable intergroup conflicts,Footnote 1 which still rage in various parts of the globe—in Sri Lanka, Kashmir, Chechnya, or the Middle East—are of special interest. Conflicts in this category stem from disagreements over contradictory goals and interests in different domains such as territories, natural resources, economic wealth, self-determination, and/or basic values, and these real issues must be addressed in conflict resolution processes. Nonetheless, it is assumed that these disagreements could potentially be resolved if not for the powerful sociopsychological barriers which fuel and maintain the conflicts (Arrow et al. 1995; Bar-Siman-Tov 1995, 2010; Bar-Tal and Halperin 2011; Ross and Ward 1995).

These barriers inhibit and impede progress toward a peaceful settlement of the conflict. They are found among both leaders and society members and stand as major obstacles to beginning negotiations for a solution, to maintaining these negotiations, to achieving an agreement, and later to engaging in a process of reconciliation. In our view, the sociopsychological barriers to conflict resolution refer to the integrated operation of cognitive, emotional, and motivational processes, combined with a preexisting repertoire of rigid conflict-supporting beliefs, worldviews, and emotions that result in selective, biased, and distorted information processing (Bar-Tal and Halperin 2011). This processing obstructs and inhibits the penetration of new information that can potentially contribute to progress in the de-escalation or peacemaking process.

The chapter will first present the evolvement of the culture of conflict that provides the foundation for the emergence of sociopsychological barriers to conflict resolution. Subsequently, it will describe the barriers’ functioning on the societal level, focusing on the mechanisms employed to maintain the culture of conflict. The next part will introduce a general integrative model of sociopsychological barriers on the individual level, focusing on cognitive, motivational, and emotional factors, and introducing the concept of self-censorship. A conceptual framework will follow, proposing ways to overcome the sociopsychological barriers. Finally, the significance of this framework and the findings supporting it will be discussed.

Development of Sociopsychological Barriers to Conflict Resolution

Evolvement of an Ideology of Conflict

Our point of departure is that intractable conflicts have an “imprinting” effect on the individual and collective lives of the participating societies’ members. The above described characteristics of intractable conflict imply that society members living under these harsh conditions experience severe and continuous negative psychological effects such as chronic threat, stress, pain, uncertainty, exhaustion, suffering, grief, trauma, misery, and hardship, both in human and material terms (see, e.g., Cairns 1996; de Jong 2002; Milgram 1986; Robben and Suarez 2000). An intractable conflict also demands the constant mobilization of society members to support and actively take part in it, even to the extent of the willingness to sacrifice their own lives. In view of these experiences, society members must adapt to the harsh conditions by satisfying their basic human needs, learning to cope with the stress, and developing psychological mechanisms that will be conducive to successfully withstanding the rival group.

We propose that in order to meet the above challenges, societies in intractable conflict develop a repertoire of functional beliefs, attitudes, emotions, values, motivations, norms, and practices (Bar-Tal 2007, 2013). This repertoire provides a meaningful picture of the conflict situation, justifies the society’s behavior, facilitates wide mobilization for participation in the conflict, effectively differentiates between the in-group and the rival, and enables the maintenance of a positive social identity and collective self-image. These elements of the sociopsychological repertoire, on both the individual and collective levels, gradually crystallize into a well-organized system of shared societal beliefs,Footnote 2 attitudes, and emotions that penetrates into the society’s institutions and communication channels and become part of its sociopsychological infrastructure. This infrastructure includes collective memories, an ethos of conflict, and collective emotional orientationFootnote 3 that are all mutually interrelated—they provide the major narratives, motivations, orientations, and goals that society members need in order to carry on with their lives under the harsh conditions of intractable conflict, while supporting its continuation.

Collective memory of conflict describes the outbreak of the conflict and its course, providing a coherent and meaningful picture of what has happened from the societal perspective (Bar-Tal 2007, 2013; Devine-Wright 2003; Papadakis et al. 2006; Tint 2010). Complementing the collective memory is the ethos of conflict, defined as the configuration of shared central societal beliefs that provide a particular dominant orientation to a society at present and for the future (Bar-Tal 2000, 2007, 2013). It is composed of eight major themes about issues related to the conflict, the in-group, and its adversary: (1) societal beliefs about the justness of one’s own goals, which outline the contested goals, indicate their crucial importance, and provide their explanations and rationales; (2) societal beliefs about security stress the importance of personal safety and national survival and outline the conditions for their achievement; (3) societal beliefs of positive collective self-image concern the ethnocentric tendency to attribute positive traits, values, and behaviors to one’s own society; (4) societal beliefs of victimization concern the self-presentation of the in-group as the victim of the conflict; (5) societal beliefs of delegitimizing the opponent concern beliefs that deny the adversary’s humanity; (6) societal beliefs of patriotism generate attachment to the country and society by propagating loyalty, love, care, and sacrifice; (7) societal beliefs of unity refer to the importance of ignoring internal conflicts and disagreements during intractable conflicts to unite the society’s forces in the face of an external threat; and, finally, (8) societal beliefs of peace refer to peace as the ultimate desire of the society but are not attached to any concrete sacrifices that must be made toward this end.

The described themes of ethos of conflict also appear in the collective memory of conflict. Together, they form a kind of ideology that provides a general worldview about the reality of conflict. As an ideology, the presented themes create a conceptual framework that allows society members to organize and comprehend the world in which they live and to act toward its preservation or alteration in accordance with this standpoint (Eagleton 1991; Jost et al. 2009; McClosky and Zaller 1984; Shils 1968; Van Dijk 1998). The ideology reflects genuine attempts to give meaning to and organize the experiences and information provided by life in the context of intractable conflict, as well as conscious or unconscious tendencies to rationalize the way things are, or alternatively, the wishes of how they should be (e.g., Jost et al. 2003). Moreover, it is a determinative factor in affecting the evaluation and judgment of conflict-related issues. The ideology affects the way society members view events of the conflict, interpret their experiences, and judge various issues that arise throughout time, including different proposed solution to resolve the conflict. In addition to the noted functions, the ideology also strengthens unity, interdependence, and solidarity, as it creates a shared view of the conflict reality based on common experiences and socialization.

In this conception, it is of crucial importance to note that this ideology provides a conservative outlook on the reality of intractable conflict (Krochik and Jost 2011). Indeed, Hogg (2004) proposed that ideologies that tend to develop under extreme uncertainty (such as intractable conflict) are conservative ideologies that resist change. In this line, the described ideology with its themes comes to preserve the existing order of continuing the conflict and thus to maintain the known and familiar without taking any risks in moving into the unknown and ambiguous territory of peacemaking. The ideology focuses on potential threats and losses in moving toward compromises with the rival and emphasizes stability and security within the present situation (Jost et al. 2003). It expresses a fear of change, because as Thórisdóttir and Jost (2011) noted, “the status quo, no matter how aversive, is a known condition and is therefore easier to predict and imagine than a potentially different state of affairs that could be either better or worse” (p. 789).

It is therefore not surprising that we found that a general conservative outlook, reflected in right-wing authoritarianism (RWA—Altemeyer 1981), predicts adherence to the ethos of conflict (Bar-Tal et al. 2012). Ethos of conflict and RWA as worldviews reflect a conservative orientation of adhering to traditional goals and known situations, closure to new ideas, and mistrust of the other—elements that lead to readily detecting threats and dangers in possible changes. This study also shows that adherence to the ethos of conflict is related to unwillingness to support compromises needed to resolve the conflict. It is individuals’ ideology about the conflict that closes them to new possibilities and makes them intransigent (see also Halperin and Bar-Tal 2011).

Eventually, the described infrastructure becomes institutionalized and is widely disseminated. Consequently, it serves as a foundation for the development of a culture of conflict that dominates societies engaged in intractable conflicts.

Culture of Conflict

A culture of conflict develops when societies saliently integrate into their culture tangible and intangible symbols that have been created to communicate a particular meaning about the prolonged and continuous experiences of living in the context of prolonged and violent conflict (Bar-Tal 2010, 2013; Geertz 1973; Ross 1998). Symbols of conflict become hegemonic elements in the culture of societies involved in intractable conflict: They provide the dominant meaning about the present reality, about the past, and about future goals and serve as guides for individual action. Ann Swidler’s (1986, p. 273) discussion of culture as “a ‘tool kit’ of rituals, symbols, stories, and world views”, which people use to construct “strategies of action,” is an important theoretical addition and can serve as a foundation for the present discussion. Bond (2004) elaborated on this psychological conception of culture in a manner fully congruent with the discussion of a culture of conflict, by defining culture as follows:

“A shared system of beliefs (what is true), values (what is important), expectations, especially about scripted behavioral sequences, and behavioral meanings (what is implied by engaging in a given action) developed by a group over time to provide the requirement of living… This shared system enhances communication of meaning and coordination of actions among culture’s members by reducing uncertainty and anxiety through making its members’ behavior predictable, understandable, and valued” (p. 62).

We suggest that the sociopsychological infrastructure’s solidification, as an indication of the development of a culture of conflict, includes the four key features: (1) Extensive sharing—The societal beliefs of the sociopsychological infrastructure and the accompanying emotions are widely shared by society members.Footnote 4 (2) Wide application—The repertoire is not only held by society members but is also put into active use by them in their daily conversations, being chronically accessible. In addition, it is dominant in the public discourse propagated by societal channels of mass communication and is often used by leaders to justify and explain decisions, policies, and courses of actions. Finally, the repertoire is also expressed in institutional ceremonies, commemorations, memorials, and so on. (3) Expression in cultural products—The sociopsychological infrastructure is also expressed through cultural products such as literary books, television programs, films, theater plays, visual art, monuments, etc. (4) Educational materials—The sociopsychological infrastructure appears in the textbooks used in schools, and even in higher education institutions, as a central theme of socialization.

The above analysis aimed to present the basis on which the sociopsychological barriers to conflict resolution evolve and grow. These barriers, which serve as powerful forces in societies involved in intractable conflicts, are grounded in the culture of conflict, with the ideological themes of the ethos and collective memory as its pillars. These themes are also grounded in shared emotions, which constitute another powerful vector to the functioning of the barriers. Taken together, these factors play a major role in preventing the processing of new information and consequently the adoption of new perspectives that could facilitate a peacemaking process. We will now elaborate on these sociopsychological barriers.

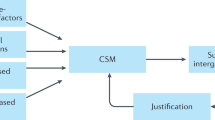

The discussion of the sociopsychological barriers is divided into two parts. The first part presents the societal mechanisms that play an active role in creating barriers to the flow of alternative information. The second part describes the nature and functioning of the barriers on the level of individual society members involved in intractable conflicts and supporting them. The main argument advanced in this chapter is that although sociopsychological barriers function on the individual level, this functioning is greatly affected by the dominant culture of conflict, which acts a filter for information about the conflict. They provide the social environment in which individual society members collect information, form experiences, and subsequently process them (see Fig. 7.1).

We propose that societies involved in intractable conflict use various societal mechanisms to block the appearance and dissemination of information providing an alternative view of the conflict, the rival, the in-group, and/or the conflict’s goals: alternative information that humanizes the rival and sheds a new light on the conflict; that suggests compromises can be made; that sees a partner on the other side with whom it is possible to achieve a peaceful settlement of the conflict; that views peace as beneficial and the conflict as costly; that views continuation of the conflict as detrimental to the society; and that may even provide evidence that the in-group also holds responsibility for the conflict’s continuation and has been acting immorally. This tendency to block alternative information can be found in every society involved in intractable conflict in the phases of escalation. At the very least, formal institutions and channels of communication practice this tendency, while informal, and often marginal, institutions and organizations may provide the alternative information even in the early phases of the conflict.

These societal mechanisms that constitute barriers will now be described.

Societal Mechanisms as Barriers

Societal mechanisms are in place to block alternative information and narratives from entering social spheres and guarantee that even when these do penetrate, they will be rejected, and society members will be unpersuaded by their evidence and arguments (Bar-Tal 2007; Horowitz 2000; Kelman 2007). Such societal mechanisms can be used by the formal authorities of the in-group—in some cases of the state—or by other agents of conflict, who have a vested interest in preventing dissemination of alternative information. The former can be governments, leaders, and societal institutions, and the latter can be NGOs and various organizations, as well as individuals who are in positions of gatekeepers of information.

-

1.

Control of information. This mechanism refers to the selective dissemination of information about the conflict within society, as practiced by formal and informal societal institutions (e.g., state ministries, the military forces, and the media). These institutions provide information that sustains the dominant conflict-supportive narrative while suppressing information that may challenge it. This is done, for instance, by selecting friendly agents for the dissemination of information, by establishing a central organization to oversee the dissemination of the official conflict-supportive narratives, and by preventing journalists or monitoring NGOs from entering particular areas of conflict-related action (Dixon 2010).

The Russians’ method for dealing with the local media during the second Russia-Chechnya War illustrates this mechanism’s employment. They established the Russian Information Center that briefed journalists and instructed Russian officials on what to tell the media. In addition, the separatists from Chechnya were effectively cut off from the media, and the Russians exercised strict control over journalists’ movements in Chechnya. Even when journalists were allowed to enter war zones, they were accompanied by Russian officials who decided where they could go and what they could see (Caryl 2000). Moreover, we can see strategic manipulations of the information through a mechanism called “gaming the system.” For instance, some members of government’s teams could selectively frame and/or distort the information through its proactive manipulation to misguide and actively bias the information that will be allowed to decision-makers (Galluccio 2011).

-

2.

Censorship. This mechanism refers to the prohibitions on the publication of information in various products (e.g., newspapers articles, cultural channels and official publications) that challenges the themes of the dominant conflict-supporting narratives. These products typically have to be submitted to a formal institution for approval before they become public (Peleg 1993). This method was used, for example, by the government of Sri Lanka in its struggle against the Tamil minority. In 1973, the government enacted the Press Council Bill that formed a censoring council whose members, appointed by the president, where authorized to prohibit the discussion in the mass media of sensitive policies and political and economic topics related to the way the conflict was being handled (Tyerman 1973).

-

3.

Restricting access to archives. This mechanism aims to prevent the public disclosure of documents stored in archives (especially state archives) that may contradict the dominant narrative (Brown and Davis-Brown 1998). Usually, such documents are evidence of the in-group’s misdeeds, including atrocities, missed opportunities to make peace, or, alternatively, information that may contradict the negative view of rival groups as depicted in the conflict-supporting narrative, such as evidence of sincere peace initiatives put forward by these groups. The prevention of access to archived documents can be comprehensive—applying to all people and all documents—or selective. For example, since World War I, the Ottoman and later the Turkish archives were closed to the public with regard to documents that pertain to the Armenian Genocide. State officials had access to such documents but only to search for documents that supported the Turkish “no genocide” narrative. In 1985, the archives were partially opened, but even then, access granted to the documents was highly selective (Dixon 2010; Safarian 1999).

-

4.

Monitoring. This mechanism, employed by formal and informal societal institutions, refers to the regular scrutiny of information that is being disseminated to the public sphere (e.g., school textbooks, NGO reports, mass media news, studies of scholars, and so on) in order to identify information that contradicts the conflict-supporting narrative, expose the sources of such information, and sanction them to prevent further dissemination of such information (Avni and Klustein 2009). The objects of this monitoring are typically mass media outlets, studies by scholars and research institutions, history textbooks, and peace NGOs’ reports. The monitoring is conducted by formal and informal societal institutions. An example of the use of monitoring can be found in the Israeli-Jewish society, with organizations such as Israel Academia Monitor (IAM) and NGO Monitor employing this mechanism widely to single out individuals, groups, and NGOs that, in their view, undermine Jewish-Zionist interests (IAM 2011).

-

5.

Discrediting of counter-information. This category encompasses methods for portraying information that supports counter-narratives and/or its sources (individuals or entities) as unreliable and as damaging to the interests of the in-group. Occasionally, these methods reach the level of delegitimization of individuals and organizations that disseminate such information (Berger 2005). The Greek population in Cyprus exemplifies extensive employment of this mechanism. Conflict-supporting governments as well as political parties, NGOs, and individuals have tried, continuously and systematically, to discredit and even delegitimize individuals, groups, and organizations that have engaged in the dissemination of information countering the prevailing views about the Turkish Cypriot conflict, the rival, and the Greek society (Papadakis et al. 2006).

-

6.

Punishment. When individuals and entities challenge the hegemony of the dominant narrative, they may face sanctions. These sanctions can be formal and/or informal and may be of social, financial, and/or physical nature. They are aimed at discouraging such challengers from conducting their activities and thereby effectively silence them (Carruthers 2000). As an illustration, this mechanism was used extensively in El Salvador during the civil war. Journalists, scholars, and students who criticized the government were constantly labeled as “destabilizers” and traitors; they were harassed, arrested, and physically attacked; their residences and offices were bombed, and some were even murdered. Harsh measures were also taken against the institutions themselves, including newspapers and even the National University of El Salvador (Matheson 1986).

-

7.

Encouragement and rewarding. This mechanism consists of “carrots” given to those sources, channels, agents, and products that support the sociopsychological repertoire of the conflict. Authorities may reward and encourage such sources for providing narrative-supporting information, knowledge, art, and other products. In the case of the mass media, for example, a particular correspondent may receive exclusive information or interviews for such favorable coverage. In the case of cultural products, the writer or painter may receive a prize for her creative work that supports the culture of conflict. The goal is to show that those who follow the line reap benefits and rewards and should serve as models for others. In this line, the Israeli minister of culture decided to award an annual prize for cultural work in the area of Zionism that comes to “express values of Zionism, the history of the Zionist movement and the return of the Jewish people to their historical homeland” (http://www.mcs.gov.il/Culture/Professional_Information/CallforScholarshipAward/Pages/PrasZionut2011.aspx).

Taken, together, these mechanisms show that societies involved in intractable conflict actively work to maintain the conflict-supporting narrative and prevent any penetration of alternative beliefs that may undermine its dominance. This social situation may be described as the monopolization of patriotism (Bar-Tal 1997). In other words, society’s dominant sector, which wishes to sustain the conflict, situates the themes of the ethos of conflict and collective memory as the only ideology that reflects true patriotism. In these cases, only those society members who accept this ideology are considered patriots, while other society members who are attached to the nation and country but do not embrace this ideology are then labeled non-patriots. Monopolization of patriotism in this case becomes a mechanism of exclusion for society members who do not hold the ideology. Consequently, society members must display unquestioning loyalty not only to the nation and state but also to the ideology.

When patriotism is monopolized, especially by a group in power, society members may conform to avoid being labeled as non-patriots. Those group members who have differing beliefs regarding the conflict and/or the rival may prefer to hide them (Mitchell 1981), as the label “non-patriot” is in itself a sanction. Other extreme labels may include “traitor,” “enemy,” or “foreign agent” and could bring about more severe sanctions in the form of tangible punishments. In addition, social psychologists have proposed that society members may accept the view of the majority and even internalize it (Allen 1965; Kelman 1961). This type of conformity essentially indicates a process of persuasion or socialization and occurs when individuals accept the view of the majority when constructing their own reality. It reflects the considerable influence that society has on individuals’ adoption of views, either through compliance, internalization, or identification processes (Kelman 1958). Such conformity may be especially present in societies that block the flow of alternative information.

In addition, when the monopolizing group is in power, it may enforce conformity not only through sanctions but also through widespread indoctrination. It may impart the limiting definition of patriotism with the ideology of conflict through various agents of socialization such as the mass media or schools. The pressure for conformity is especially effective when the regime has the control over the socialization and communication institutions on the one hand and has the power to sanction dissenters on the other.

The described societal barriers illuminate the context in which societies function on the collective level. Nevertheless, it is important to note that although in every society these mechanisms appear to at least some degree, societies involved in intractable conflict differ with regard to the extent of their use. Their appearance depends on various cultural, political, societal, and even international determinants. One of the important categories of variables that influence the development of these processes is the society’s structural characteristics and especially its political culture (Almond and Verba 1989). Of special importance is its level of openness, pluralism, tolerance, and freedom of speech, elements that have determinative influence on overall control of information, freedom of expression, openness to considering alterative information, free flow of information, availability of free agents of information, access to global sources of information, and so on. The higher the level of control the society exercises over its members, the less freedom there is to consider alternative information. A society that limits pluralism, skepticism, or criticism prevents the emergence of alternative ideas that may push toward the peaceful resolution of the conflict.

Societies in conflict also differ from one another with regard to the need to use societal mechanisms to obstruct the flow of alternative information. In asymmetrical conflicts, one society may have a more solidified moral epistemic basis in line with international moral codes than the other. This epistemic basis requires less employment of societal censorship mechanisms, as, for example, in the case of Blacks in South Africa or Algerians in Algeria demanding an end to legal discrimination and colonialism, respectively. Other societies, however, may need to construct epistemic bases that negate the normative moral codes of intergroup behavior. Such societies will also need to use societal mechanisms in order to uphold this narrative, as in the case of the Whites in South Africa and the French during the Algerian War.

Moreover, it is important to note that the described societal processes and mechanisms greatly influence the way society members think, process information, and act. Individuals’ behavior is embedded within the societal context with its special conditions. The context not only provides the space in which society members can act cognitively, emotionally, and behaviorally, but also serves, as noted, to encourage or limit these actions. The more leeway is provided to individuals, the more they can flourish and provide new, creative, and innovative ideas. We now turn the discussion toward the functioning of the sociopsychological barriers on the individual level.

Individual Sociopsychological Barriers

The discussion of the sociopsychological barriers on the individual level must begin with the understanding that in all the societies involved in intractable conflicts, in their climax, at least a significant portion of the society members hold in their repertoire the ideology of the ethos of conflict and collective memory, and some even hold them with great confidence (Sharvit 2008). These ideological conflict-supporting narratives form the pillars of the culture of conflict, illuminating the conflict in a particular light. Theoretically, the conflict-supporting narratives could be easily changed in the face of persuasive arguments that provide information about the costs of the conflict, the rival’s humanity, the rival’s willingness to negotiate a peaceful resolution, past immoral acts by the in-group, and so on. In reality, however, this change rarely occurs over a short period of timeFootnote 5—even when society members are presented with valid alternative information that refutes their beliefs, they continue to adhere to them. Sociopsychological barriers, defined as “an integrated operation of cognitive, emotional and motivational processes, combined with pre-existing repertoire of rigid conflict supporting beliefs, world views and emotions that result in selective, biased and distorting information processing” (Bar-Tal and Halperin 2011, p. 220), are a central reason for the described stalemate. Thus, the barriers’ operation at the level of the individual results in one-sided information processing that obstructs and inhibits the penetration of new information that may lead to support for the conflict’s peaceful resolution. Consequently, regardless of the availability of such information, individuals are not even interested in exposure to alternative information that may contradict their long-held ideological narratives about the conflict.

The reason for this unwillingness to hear alternative information is freezing of these beliefs, which is the essence of barriers’ functioning (Kruglanski 2004; Kruglanski and Webster 1996). The state of freezing is evidenced by the continued reliance on the conflict-supporting narratives, the reluctance to search for alternative information, and the resistance to persuasive counterarguments (Kruglanski 2004; Kruglanski and Webster 1996; Kunda 1990). The narratives of the culture of conflict freeze due to the operation of cognitive, motivational, and emotional processes, as well as a number of sociopsychological factors on which we will now elaborate (see also the integrative model of sociopsychological barriers to peacemaking in Bar-Tal and Halperin 2011 for further elaboration). We begin by describing the cognitive processes, with a focus on the rigid structure of these societal beliefs.

The Cognitive Structural Factor

“Cognitive processes are the modalities, with which every individual structures the knowledge of himself and of the world, and they are ‘imbued’ of emotions and meanings” (Aquilar and Galluccio 2008, p. 40). As a cognitive process, freezing is fed by the rigid structure of the societal conflict-supporting beliefs of the narratives. Rigidity implies that these societal beliefs are resistant to change, as they are organized in a coherent manner with little complexity and great differentiation from alternative beliefs (Tetlock 1989; Rokeach 1960). Several factors cause this rigid structure. First, societal beliefs about the conflict are often interrelated in an ideological structure. These beliefs, together, subscribe to all the criteria for being an ideology, and as such, they provide a well-organized system that may withstand counterarguments and new information and is difficult to change (Jost et al. 2003). Second, as stated earlier, these beliefs satisfy important human needs such as needs for certainty, meaningful understanding, predictability, safety, mastery, positive self-esteem and identity, differentiation, justice, etc. (Bar-Tal 2007; Burton 1990; Kelman and Fisher 2003; Staub and Bar-Tal 2003). Because they fulfill such primary needs, any change in these beliefs may be psychologically costly to the individual. Finally, the beliefs are ego-involving and are also held by many society members with high confidence as central and important, contributing to their stability. All these factors contribute to the rigid structure of the societal beliefs of the ethos of conflict and collective memory, preventing it from transformation in more conciliatory beliefs (Petrocelli et al. 2007; Eagly and Chaiken 1993, 1998; Fazio 1995; Jost et al. 2003; Krosnick 1989; Lavine et al. 2000).

It is important to note in the discussion of the cognitive factor that this closed-mindedness is also affected by general worldviews, which are systems of beliefs that are unrelated to the particular conflict but provide orientations that contribute to the conflict’s continuation because of the perspectives, norms, and values forming them (Bar-Tal and Halperin 2011). Since their childhood, individuals develop certain beliefs about themselves, other people, and the world, which drive the perception, processing, and recall of information. People core beliefs are understandings that are so fundamental and deep that they regard them as absolute truths (Aquilar and Galluccio 2008). The list of these general worldviews is a long one, but prominent examples include political ideology (such as authoritarianism or conservatism) that is not directly related to the conflict (Adorno et al. 1950; Altemeyer 1981; Jost 2006; Sidanius and Pratto 1999), specific values such as those related to power or conservatism (Schwartz 1992), religious beliefs (Kimball 2002), and an entity theory about the nature of human qualities (Dweck 1999). All these worldviews influence how society members perceive the conflict and form their beliefs about the nature of the conflict, the rival, and their own group (see, e.g., Beit-Hallahmi and Argyle 1997; Dweck and Ehrlinger 2006; Golec and Federico 2004; Jost et al. 2003; Maoz and Eidelson 2007; Sibley and Duckit 2008).

The Motivational Factor

The second factor leading to freezing is motivational because the held societal beliefs have at their base specific closure needs (see Kruglanski 1989, 2004; Chap. 16). That is, society members are motivated to view the narratives of ethos of conflict and collective memory as truthful and valid because they fulfill for them various needs (see, e.g., Burton 1990). Therefore, society members use various cognitive strategies to increase the likelihood of reaching particular conclusions that are in line with these narratives (Kunda 1990). As part of this motivational process, they reject information that contradicts the held conflict-supporting narratives but readily accept information that supports their desired conclusion.

The Emotional Factor

The third factor that affects freezing comprises enduring negative intergroup emotions. They function to limit the psychological repertoire of society members and strengthen the rigidity of their societal beliefs. The emotions are linked to the societal beliefs through their appraisal component: Each and every emotion is related to a unique configuration of comprehensive (conscious or unconscious) evaluations of the emotional stimulus (Roseman 1984), and this means that emotions are both interpreted in view of the societal beliefs and reinforce the beliefs once they are evoked. Hence, emotions and beliefs are closely related and reinforce each other continuously. More specifically, the societal beliefs of the culture of conflict are strongly related to negative emotions such as fear, hatred, and anger, widely shared by society members. Once these emotions are established and maintained as lasting emotional sentiments, they activate thoughts in line with the societal beliefs of the ethos (Halperin et al. 2011b).

A typical example of a negative emotion that often has an obstructing effect on peacemaking processes is the chronic fear that is often an inherent part of the psychological repertoire of society members involved in intractable conflict. In many cases, fear in this violent context may even lead to the development of collective angst, which indicates a perception of the group’s possible extinction (Wohl and Branscombe 2008; Wohl et al. 2010). The prolonged experience of severe fear leads to a number of observed cognitive effects that intensify freezing. It sensitizes the organism and the cognitive system to certain threatening cues. It prioritizes information about potential threats and causes extension of the associative networks of information about threat. It causes overestimation of danger and threat. It facilitates the selective retrieval of information related to fear. It increases expectations of threat and dangers, and it increases the accessibility of procedural knowledge that was effective in coping with threatening situations in the past (Clore et al. 1994; Gray 1987; Isen 1990; Lazarus and Folkman 1984; LeDoux 1995, 1996; Öhman 1993). It may also lead to repression and, consequently, to the unchecked influence of unconscious affect on behavior (Czapinski 1988; Jarymowicz 1997).

Moreover, once fear is evoked, it limits the activation of other regulatory mechanisms and limits consideration of alternative coping strategies, due to its egocentric and maladaptive patterns of reaction to situations that require creative and novel solutions for coping. Indeed, empirical findings demonstrate that fear has limiting effects on cognitive processing, and it tends to cause: adherence to known situations and avoidance of risky, uncertain and novel ones; cognitive freezing, which reduces openness to new ideas; and resistance to change (Clore et al. 1994; Isen 1990; Jost et al. 2003; Le Doux 1995, 1996; Öhman 1993).

Taking a societal approach, the collective fear orientation tends to limit society members’ perspective by binding the present to past experiences related to the conflict and by building expectations for the future exclusively on the basis of the past (Bar-Tal 2001). This seriously hinders the disassociation from the past needed to allow creative thinking about new alternatives that may resolve the conflict peacefully. As fear is deeply entrenched in the psyche of society members, as well as in the culture, it inhibits the evolvement of hope for peace by spontaneously and automatically flooding the consciousness, making it difficult for society members to free themselves from fear’s hold (Jarymowicz and Bar-Tal 2006). This dominance of fear over hope is well documented in previously presented studies of negativity bias.

In an experimental survey conducted among a representative nationwide sample of Jewish-Israelis in the week prior to the Annapolis peace, Halperin (2011) demonstrated the operation of certain negative emotions. The study’s findings demonstrated that fear and hatred function as clear barriers to the peacemaking process. Fear was found to reduce support for territorial compromises that might lead to security problems. Hatred was found to be an even stronger emotional barrier to peace, and it appears to be the only emotion that reduces support for symbolic compromises and to reconciliation and even stands as an obstacle to every attempt to acquire positive knowledge about the Palestinians. In addition, hatred was found to increase support for halting negotiations and, when coupled with fear, it predicted support for military action (see also Bar-Tal 2001; Baumeister and Butz 2005; Lake and Rothchild 1998; Petersen 2002).

The Process

In sum, freezing, triggered by numerous factors, is the dominant reason why the societal beliefs of the culture of conflict function as sociopsychological barriers. These barriers lead to selective collection of information, which means that society members involved in intractable conflict tend to search and absorb information that validates their held societal beliefs while ignoring and omitting contradictory information (Kelman 2007; Kruglanski 2004; Kruglanski and Webster 1996; Kunda 1990). But even when ambiguous or contradictory information is absorbed, it is encoded and cognitively processed in accordance with the held repertoire through bias, addition, and distortion. Figure 7.2 graphically depicts the described process.

Recently, intriguing experiments by Klar and Baram clearly demonstrated that exposure to the narrative of the other side is an ego-depleting experience, meaning that it demands significant energy and mental resources, as it is a psychological burden. They also illustrated how rival groups process information about competing narratives. In their study, participants, both Jewish and Arab, were each presented with one of two identical stories—but the protagonist in each was different: either a real Jewish or a real Palestinian leader of a paramilitary group. Ninety minutes later, the participant was asked to reconstruct the story. The results showed that both Jews and Arabs added positive details to the story of their group’s hero and omitted negative ones. On the other hand, the participants also added negative details and omitted positive ones from the story about the rival group’s leader (Klar 2011; Klar and Baram 2011). Other studies along this line have demonstrated that cognitive processes are so biased in favor of the initial narratives people possess, that it is very hard for them to change these narratives, even when the narratives are proven to be wrong (Ecker et al. 2010; Lewandowsky et al. 2009).

Moreover, because the repertoire is imparted on society members in the early years of childhood via societal institutions and channels of communications, almost all members of the young generation presumably absorb the contents of the societal beliefs of the culture of conflict. A recent study by Ben Shabat (2010) confirmed this assumption, showing that young Israeli children at the age of 6–8 tend to adhere to societal beliefs of the ethos of conflict even when their parents support peacemaking. Thus, it appears that the systematic presentation of these themes in cultural products and educational institutions leads society members, even at a very young age, to view the conflict-supporting societal beliefs as valid and truthful. When a serious peace process begins and progresses, at least some of these society members may acquire alternative beliefs that promote peacemaking, but recent important empirical findings in Israel reveal that even when society members acquire and adhere to alternative beliefs and attitudes that support peacemaking, the learned repertoire at the early age continues to be stored in their minds as implicit beliefs and attitudes. Consequently, it has an automatic influence on information processing and decision-making in times of stress (Sharvit 2008).

Self-Censorship

Self-censorship is another sociopsychological phenomenon that contributes to freezing and closure (Bar-Tal 2013). Self-censorship is defined as an act of voluntarily and intentionally withholding information from others on the basis of a belief that it may have negative implications for the individual and/or the collective. In intractable conflicts, self-censorship takes place when society members, as individuals, intentionally withhold information that they think may shed negative light on the in-group. We differentiate between two types of individuals who may practice self-censorship: gatekeepers and ordinary individuals. Gatekeepers are individuals officially charged with information dissemination. That is, they work in institutions that provide, transmit, and disseminate information (e.g., mass media, governmental information-provision institutions, schools, etc.). In contrast, ordinary individuals are individuals who do not fulfill roles related to information dissemination in the society but may nonetheless come into possession of information with relevance to society and decide not to reveal it. We suggest that there are at least three ways of receiving information that may reflect negatively on the in-group and consequently self-censored. A person may obtain it firsthand through an experience (e.g., participating in a controversial event), a person may find such information as recorded by another person (e.g., finding an archived document), or a person may obtain the information from another person who either heard/read about it or experienced it. As stated, the possessed information may harm the group’s positive image and/or goals, and/or it may provide an alternative view of the conflict, incongruent with the dominant conflict-supporting narrative. In any of these cases, the information negates the dominant beliefs that are widely shared by society members. Thus, the dominant motivation to practice self-censorship is the wish to avoid harming the society or its central beliefs. A person may also be motivated to self-censor out of a fear of negative sanctions that may be imposed on him/her for exposing the information. This sociopsychological mechanism is widely practiced by society members involved in intractable conflict, especially among those who participated, observed, or heard about immoral acts committed by the in-group.

Recently, Nets-Zehngut et al. (2014) carried out a study to examine whether, how, and to what extent gatekeepers in Israeli state institutions practiced self-censorship with regard to information that was incongruent with the dominant conflict-supporting narrative in Israel. Specifically, gatekeepers in the governmental Publications Agency of the National Information Center, the Information Branch in the Israeli army Education Corps, and the Ministry of Education self-censored information about the causes of the Palestinian exodus in the 1948 War, which saw approximately 700,000 Palestinians leave the area in which the State of Israel was established. Despite the fact that even Israeli historians provided unequivocal evidence that some of these Palestinians were forcefully expelled, the gatekeepers, confessing to self-censorship, continued to publish only information reflecting the Israeli-Jewish-Zionist narrative that takes no responsibility for the exodus, attributing it solely to the Arabs and Palestinians, for encouraging flight or fleeing, respectively. With regard to the same case, Ben Ze’ev (2010, 2011) interviewed Jewish soldiers who participated in the 1948 War. She found that many of them imposed silence on themselves, practicing self-censorship in order to block information about immoral acts committed during this war that may have shed a negative light on the Jewish fighters and leadership.

Obedience

Another sociopsychological mechanism on the individual level that leads to solidification of culture of conflict and stability is obedience. Obedience refers to the blind execution of orders without any consideration of their meaning or implication, as demonstrated in Stanley Milgram’s (1974) seminal studies. It “is the psychological mechanism that links individual behavior to political purpose. It is the dispositional cement that blinds men to systems of authority. Facts of recent history and observation in daily life suggest that for many people obedience may be a deeply ingrained behavior tendency, indeed, a prepotent impulse overriding training in ethics, sympathy and moral conduct” (Milgram 1974, p. 1). Obedience leads first and foremost to blind acceptance of the conflict ideology and thus supports the conflict’s continuation as advocated by the authorities. Moreover, it often leads to severe consequences in the cases of intractable conflicts, as many society members, blindly following orders, participate in acts of violence, including severe violations of laws, moral codes, and human rights principles (Benjamin and Simpson 2009). This is one of the plagues of human beings, and its imprinting effects can be found in most of the atrocities, massacres, ethnic cleanings, and genocides throughout history. The violent nature of intractable conflicts provides ample opportunities for human beings to exhibit such behavior, with all its inhumane implications. They obediently follow the orders in line with the beliefs delegitimizing the rival, without considering their moral implications. This sociopsychological mechanism is mostly carried out by active fighters in the conflict, whose role is to face and fight the enemy, but is also widely practiced by society members fulfilling different roles in the well-developed system that sustains the conflict.

Conclusion and Future Directions

The theory and findings presented thus far help understand the many factors contributing to the perceived intractability of intractable conflicts. First and foremost, societies in conflict develop conflict-supporting ideologies, consisting of societal beliefs that serve as building blocks of narratives about the past (collective memory) and the present (ethos of conflict). These ideologies become highly central and deeply entrenched in these societies on both the individual and collective levels, forming an all-encompassing culture of conflict that permeates into every aspect of collective, and often individual, life. Several mechanisms exist on the societal level to maintain and further promote this culture of conflict. The leaderships in societies in conflict usually operate official bodies for the dissemination of information, granting them control over which facts are presented to the public and how. To further maintain control over what the public knows, these leaderships also work to restrict access to official archives, monitor unofficial organizations attempting to disseminate alternative information, and discredit alternative information when such is successfully disseminated. Furthermore, mechanisms for actual censorship of information may be employed, and anyone presenting information undermining the accepted societal beliefs may be severely punished for doing so. Conversely, individuals and organizations disseminating information in line with these beliefs may be encouraged to continue doing so through tangible and symbolic rewards.

But the culture of conflict is also maintained on the individual level. Various psychological factors contribute to the tendency for freezing among individuals in societies involved in intractable conflict. First, a central cognitive factor contributing to freezing is the tendency to adhere to certain general and specific worldviews for the sake of organizing reality and one’s approach to it and attending only to information that conforms to these beliefs. Second, motivational factors, such as people’s desire to maintain a positive self- and collective self-view and their desire to avoid sanctions, contribute to such freezing. Finally, because the reality of living in an intractable conflict is wrought with emotion, people’s group-based emotions are a central factor in their need to maintain the beliefs of the culture of conflict. In addition to these three psychological factors, and in line with the societal mechanisms limiting the penetration of alternative information, people may voluntarily practice self-censorship with regard to alternative information, for fear that it may lead to negative consequences for the group or the self. Thus, many factors act together and separately, placing barriers before attempts to resolve the conflict peacefully.

Overcoming Barriers to Conflict Resolution

While the combined action of sociopsychological barriers to conflict resolution may paint a bleak picture as to the possibility to move intractable conflicts into the stage of resolution and reconciliation, the literature also provides many indications that such barriers can be overcome given the right circumstances or interventions. In most of the cases, peacemaking requires bottom-up processes in which groups and individuals publicly support the ideas of peacebuilding and act to persuade the leadership leaders. But it also requires top-down processes in which emerging leaders join efforts or initiate peacemaking processes and work to persuade society members of the necessity of a peaceful settlement of the conflict. For these to occur, conditions on the ground must become favorable (Bar-Tal 2013).

Conditions for Change

Some scholars of conflict resolution argue that the success of peacemaking processes depends on specific conditions that create ripeness for the conflict’s resolution. For example, Zartman (2000, pp. 228–229) proposes that “if the (two) parties to a conflict (a) perceive themselves to be in a hurting stalemate and (b) perceive the possibility of a negotiated solution (a way out), the conflict is ripe for resolution (i.e., for negotiations toward resolution to begin).” Indeed, the thought of peacefully resolving the conflict often emerges and spreads when changes in the context of the conflict are observed. These changes pertain to major events and/or information that may facilitate the process of peacemaking and may be termed “facilitating conditions.” Among the most salient of these are confidence-building actions by the rival, which may change perceptions of the opponents’ character, intentions, and goals. Another facilitating condition pertains to the emergence of major information about the society’s endurance. The realization of the costs to the society in continuing the conflict may lead to greater willingness to compromise or peace. Third party intervention, including third party guarantees, may also be a determining condition in changing views about the conflict or about the risks contained in resolving it. The noted conditions are neither exhaustive nor exclusive, and each may arouse new needs or goals that could foster societal change. They may also lead to unfreezing of the conflict-supporting sociopsychological repertoire on the individual level, a key factor in moving both of conflict resolution processes forward.

Unfreezing Process

According to the classic conception offered by Lewin (1947/1976), every process of societal change has to begin with cognitive change. In individuals and groups, this indicates unfreezing, which is thus a precondition for the acceptance and internalization of any alternative beliefs about the conflict. In many of the conflict situations, this process begins with a minority, which needs also to have courage in order to present the alternative ideas to society members in the face of the societal mechanism in place to prevent the dissemination of such ideas. On the psychological individual level, the process of unfreezing usually begins as a result of the appearance of a new idea that is inconsistent with the held beliefs and attitudes and causes to some kind of tension or dilemma (e.g., Abelson et al. 1968; Bartunek 1993; Kruglanski 1989). This new idea is called an instigating belief, since it motivates society members who construct it to evaluate the held societal beliefs of culture of conflict (see elaboration in Bar-Tal and Halperin 2009). Due to the powerful nature of the societal mechanisms in place to prevent the penetration of new ideas, the instigating belief must be of high validity, and/or coming from a credible source, forcing the individual to pause and consider the conflicting information.

Once such an idea is absorbed and considered, it may eventually lead to the emergence of a new mediating belief, calling for a change in the context of intractable conflict. The mediating belief is one logical outcome of the tension caused by the instigating belief, if it is resolved in the direction of accepting the new belief (see the intrapersonal sociopsychological process described by Kruglanski 1989). Mediating beliefs are usually stated in the form of arguments: “We must change strategy or we are going to suffer further losses,” “Some kind of change is inevitable,” “We have been going down a self-destructive path; we must alter our goals and strategies,” “The proposed change is clearly in the national interest; it is necessary for national security” (Bar-Siman-Tov 1995). These arguments open a discussion of alternatives to the present reality, including a peaceful settlement of the conflict. Empirical evidence for the effects of such ideas comes from a study conducted together with other colleagues (Gayer et al. 2009). In this study, conducted among Jews in Israel, we found that instigating beliefs that include information about future losses in various aspects of life (e.g., economic and demographic aspects, as well as potential negotiations with Palestinians) unfreezes Israelis’ predispositions about the peace process with the Palestinians.

However, for such beliefs to take hold substantially, several barriers on the individual level must be overcome. A few promising indications in the recent literature in political psychology indicate that it may be possible to tangibly overcome these barriers by tackling each of the three factors contributing to the freezing of the conflict-supporting ideology: the cognitive factor, the motivational factor, and the emotional factor. The cognitive factor, which includes long-standing beliefs, may appear most resistance to change, but in a recent series of studies, Nasie and colleagues have shown that merely raising people’s awareness to a common psychological bias may facilitate unfreezing of long-standing beliefs. When both Jewish and Palestinian citizens of Israel were made aware of naïve realism, a cognitive bias limiting their ability to recognize beliefs other than their own as valid, they were more open to new information presenting the adversary’s beliefs on the conflict, even though this information was entirely incongruent with their own long-held beliefs (Nasie et al. 2013).

Indications also exist that various conditions may serve to change important motivational factors contributing to freezing. In the classical literature on obedience, there are already indications that altering the conditions of the situation may lead to decreased obedience to authority—countering the central motivation to obey authority so as to gain rewards and avoid sanctions. More specifically, Milgram has identified the victim’s proximity, closeness to the authority figure, and the salience of a tension or dilemma as conditions that may be changed so as to decrease people’s willingness to obey orders that may hurt others (Milgram 1965). Similarly, scholars studying conformity have identified a minority influence effect, by which the presence of others doubting the majority’s view, even if they are few, decreases the likelihood an individual would be motivated to conform (for a review, see Wood et al. 1994). More recent indication that the motivations underlying freezing may be changed exists as well. For example, Čehajić-Clancy and colleagues have found that affirming a positive aspect of the self can increase one’s willingness to acknowledge in-group responsibility for wrongdoing against others, countering the motivation to maintain a positive view of the in-group at all costs (Čehajić-Clancy et al. 2011).

Finally, many studies conducted over the past decade have indicated that changing the emotional factor contributing to freezing may be an important key for overcoming psychological barriers to conflict resolution, as emotions are both powerful engines for action and highly changeable (Halperin 2014), through the study of emotion and emotion regulation in political conflicts (e.g., Aquilar and Galluccio 2008; Halperin et al. 2011b). For example, these studies show that by employing well-established methods of emotion regulation, previously tested only on the personal level, group-based emotions may be changed as well, consequently influencing intergroup attitudes (e.g., Halperin et al. 2014). More importantly, it appears that teaching people how to regulate their emotions using such strategies may increase their willingness to compromise for peace even several months after the initial intervention (Aquilar and Galluccio 2008; Halperin et al. 2013). Another interesting approach to affecting emotional change, and consequently attitudinal change, is to tackle a key appraisal implicated in a certain discrete emotion, thereby changing the emotional reaction as well. For example, studies employing this approach have succeeded in reducing group-based hatred (Halperin et al. 2011a) and increasing group-based hope (Cohen-Chen et al. 2014) and guilt (Čehajić-Clancy et al. 2011).

Taken together, these empirical developments provide important evidence that despite the many challenges facing those who want to achieve peaceful resolutions to long-standing violent conflicts, such resolutions are not altogether elusive. Understanding the sociopsychological barriers to conflict resolution, which are important contributors to the intractable nature of such conflicts, helps understand how such barriers can be overcome. A downstream consequence of such scientific findings may be an improvement in practitioners’ ability to affect the social change needed to create the conditions for peacemaking to succeed in societies engulfed in intractable conflict.

Peace should not be a dream but a practical goal that human beings should strive to achieve. Violent conflicts are not natural disasters but well-planned events by human beings who also deliberately kill and are killed. The efforts, resources, and mobilization that are invested in eruption of conflicts and their continuation should be redirected to peacemaking. Human beings can make peace.

Notes

- 1.

Intractable conflicts are violent, fought over goals viewed as existential, perceived as being of zero sum nature and unsolvable, preoccupy a central position in the lives of the involved societies, require immense investments of material and psychological resources, and last for at least 25 years (Bar-Tal 2007a, 2013; Kriesberg 1993).

- 2.

Societal beliefs are the building blocks of narratives. They are defined as shared cognitions by the society members that address themes and issues that the society members are particularly occupied with and which contribute to their sense of uniqueness (Bar-Tal 2000).

- 3.

- 4.

It is recognized that not all members of societies involved in intractable conflict share equally the repertoire. Societies differ in the extent of sharing the societal beliefs of ethos and of collective memory. Moreover, there are societies that hold contradicting ethos even at the height of the conflict and others may develop it with time.

- 5.

Still the process of change may take place with great difficulty, duration and obstacles.

References

Abelson, R. P., Aronson, E., McGuire, W. J., Newcomb, T. M., Rosenberg, M. J., & Tannenbaum, P. H. (Eds.). (1968). Theories of cognitive consistency: A sourcebook. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., & Sanford, R. N. (1950). The authoritarian personality. New York, NY: Harper.

Allen, V. I. (1965). Situational factors in conformity. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 133–175). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Almond, G. A., & Verba, S. (1989). The civic culture: Political attitudes and democracy in five nations. London: Sage.

Altemeyer, B. (1981). Right-wing authoritarianism. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

Aquilar, F., & Galluccio, M. (2008). Psychological processes in international negotiations. New York: Springer.

Arrow, K. J., Mnookin, R. H., Ross, L., Tversky, A., & Wilson, R. (1995). Barriers to conflict resolution. New York: W. W. Norton.

Avni, L., & Klustein, E. (2009). Trojan horse: The impact of European government funding for Israeli NGOs. Jerusalem: NGO Monitor.

Bar-Siman-Tov, Y. (1995). Value-complexity in shifting form war to peace: The Israeli peace-making experience with Egypt. Political Psychology, 16, 545–565.

Bar-Siman-Tob, Y. (2010). Barriers to peace in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Jerusalem: The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies.

Bar-Tal, D. (1997). The monopolization of patriotism. In D. Bar-Tal & E. Staub (Eds.), Patriotism in the life of individuals and nations (pp. 246–270). Chicago, IL: Nelson Hall.

Bar-Tal, D. (1998). Societal beliefs in times of intractable conflict: The Israeli case. International Journal of Conflict Management, 9, 22–50.

Bar-Tal, D. (2000). Shared beliefs in a society: Social psychological analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bar-Tal, D. (2001). Why does fear override hope in societies engulfed by intractable conflict, as it does in the Israeli society? Political Psychology, 22, 601–627.

Bar-Tal, D. (2007a). Living with the conflict: Socio-psychological analysis of the Israeli-Jewish society. Jerusalem: Carmel (in Hebrew).

Bar-Tal, D. (2007b). Sociopsychological foundations of intractable conflicts. American Behavioral Scientist, 50, 1430–1453.

Bar-Tal, D. (2010). Culture of conflict: Evolvement, institutionalization, and consequences. In R. Schwarzer & P. A. Frensch (Eds.), Personality, human development, and culture: International perspectives on psychological science (Vol. 2, pp. 183–198). New York: Psychology Press.

Bar-Tal, D. (2013). Intractable conflicts: Socio-psychological foundations and dynamics. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Bar-Tal, D., & Halperin, E. (2009). Overcoming psychological barriers to peacemaking: The influence of beliefs about losses. In M. Mikulincer & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Prosocial motives, emotions and behavior: The better angels of our nature (pp. 431–448). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bar-Tal, D., & Halperin, E. (2011). Socio-psychological barriers to conflict resolution. In D. Bar-Tal (Ed.), Intergroup conflicts and their resolution: Social psychological perspective (pp. 217–240). New York: Psychology Press.

Bar-Tal, D., Sharvit, K., Halperin, E., & Zafran, A. (2012). Ethos of conflict: The concept and its measurement. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 18, 40–61.

Baumeister, R. F., & Butz, J. (2005). Roots of hate, violence and evil. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), The psychology of hate (pp. 87–102). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bartunek, J. M. (1993). The multiple cognitions and conflict associated with second order organizational change. In J. K. Murnighan (Ed.), Social psychology in organizations: Advances in theory and research (pp. 322–349). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Beit-Hallahmi, B., & Argyle, M. (1997). The psychology of religious belief, behaviour and experience. London: Routledge.

Ben Shabat, C. (2010). Collective memory and ethos of conflict acquisition during childhood: Comparing children attending state-secular and state-religious schools in Israel. Master thesis submitted to Program in Counseling Education, School of Education, Tel Aviv University (in Hebrew).

Benjamin, L. T., Jr., & Simpson, J. A. (2009). The power of the situation: The impact of Milgram’s obedience studies on personality and social psychology. American Psychologist, 64, 12–19.

Ben-Ze’ev, E. (2010). Imposed silences and self-censorship: Palmach soldiers remember 1948. In E. Ben-Ze’ev, R. Ginio, & J. Winter (Eds.), Shadows of war—A social history of silence in the twentieth century (pp. 173–180). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ben-Ze’ev, E. (2011). Remembering Palestine in 1948: Beyond national narratives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Berger, S. (2005). A return to the national paradigm? National history writing in Germany, Italy, France, and Britain from 1945 to the present. The Journal of Modern History, 77, 629–678.

Bond, M. H. (2004). Culture and aggression-from context to coercion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8, 62–78.

Brown, R., & Davis-Brown, B. (1998). The making of memory: The politics of archives, libraries and museums in the construction of national consciousness. History of the Human Sciences, 11, 17–32.

Burton, J. W. (Ed.). (1990). Conflict: Human needs theory. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Cairns, E. (1996). Children in political violence. Oxford: Blackwell.

Carruthers, S. (2000). The media at war: Communication and conflict in the twentieth century. New York: Palgrave.

Caryl, C. (2000). Objectivity to order: Access is the key problem for journalists reporting on the second Chechen war, and is under tight military control. Index on Censorship, 29, 17–20.

Čehajić-Clancy, S., Effron, D. A., Halperin, E., Liberman, V., & Ross, L. D. (2011). Affirmation, acknowledgment of in-group responsibility, group-based guilt, and support for reparative measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 256.

Clore, G. L., Schwarz, N., & Conway, M. (1994). Affective causes and consequences of social information processing. In R. S. Wyer & T. K. Strull (Eds.), Handbook of social cognition (Vol. 1, pp. 323–417). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cohen-Chen, S., Halperin, E., Crisp, R. J., & Gross, J. J. (2014). Hope in the Middle East: Malleability beliefs, hope, and the willingness to compromise for peace. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(1), 67–75.

Czapinski, J. (1988). Informational aspects of positive–negative asymmetry in evaluations. Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift der Friedrich-Schiller-Universitat, Gesellschaft-wissenschaftliche Reihe, 37, 647–653.

de Jong, J. T. V. M. (Ed.). (2002). Trauma, war, and violence: Public mental health in socio-cultural context. New York: Kluwer.

Devine-Wright, P. (2003). A theoretical overview of memory and conflict. In E. Cairns & M. D. Roe (Eds.), The role of memory in ethnic conflict (pp. 9–33). Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dixon, J. M. (2010). Defending the nation? Maintaining Turkey’s narrative of the Armenian genocide. South European Society and Politics, 15, 467–485.

Dweck, C. S. (1999). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality and development. Philadelphia, PA: Taylor and Francis/Psychology Press.

Dweck, C. S., & Ehrlinger, J. (2006). Implicit theories and conflict resolution. In M. Deutsch, P. T. Coleman, & E. C. Marcus (Eds.), The handbook of conflict resolution: Theory and practice (2nd ed., pp. 317–330). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Eagleton, T. (1991). Ideology: An introduction (Vol. 9). London: Verso.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1998). Attitude structure and function. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (Vol. 1, 4th ed., pp. 269–322). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Ecker, U., Lewandowsky, S., & Tang, D. (2010). Explicit warnings reduce but do not eliminate the continued influence of misinformation. Memory and Cognition, 38(8), 1087–1100.

Fazio, R. H. (1995). Attitudes as object-evaluation associations: Determinants, consequences, and correlates of attitude accessibility. In R. E. Petty & J. A. Krosnick (Eds.), Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences (pp. 247–282). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Galluccio, M. (2011). Transformative leadership for peace negotiation. In F. Aquilar & M. Galluccio (Eds.), Psychological and political strategies for peace negotiations: A cognitive approach. New York: Springer.

Gayer, C. C., Landman, S., Halperin, E., & Bar-Tal, D. (2009). Overcoming psychological barriers to peaceful conflict resolution: The role of arguments about losses. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 53, 951–975.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. New York: Basic Books.

Golec, A., & Federico, C. M. (2004). Understanding responses to political conflict: Interactive effects of the need for closure and salient conflict schema. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 750–762.

Gray, J. A. (1987). The psychology of fear and stress (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Halperin, E. (2011). Emotional barriers to peace: Negative emotions and public opinion about the peace process in the Middle East. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 17, 22–45.

Halperin, E. (2014). Emotion, emotion regulation, and conflict resolution. Emotion Review, 6(1), 68–76.

Halperin, E., & Bar-Tal, D. (2011). Socio-psychological barriers to peace making: An empirical examination within the Israeli Jewish society. Journal of Peace Research, 48, 637–657.

Halperin, E., Pliskin, R., Saguy, T., Liberman, V., & Gross, J. J. (2014). Emotion regulation and the cultivation of political tolerance: Searching for a new track for intervention. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 58(6), 1110–1138. doi:10.1177/0022002713492636.

Halperin, E., Porat, R., Tamir, M., & Gross, E. (2013). Can emotion regulation change political attitudes in intractable conflict? From the laboratory to the field. Psychological Science, 24, 106–111.

Halperin, E., Russell, G. A., Trzesniewski, H. K., Gross, J. J., & Dweck, S. C. (2011a). Promoting the peace process by changing beliefs about group malleability. Science, 333, 1767–1769.

Halperin, E., Sharvit, K., & Gross, J. J. (2011b). Emotions and emotion regulation in conflicts. In D. Bar-Tal (Ed.), Intergroup conflicts and their resolution: A social psychological perspective (pp. 83–103). New York: Psychology Press.

Hogg, M. A. (2004). Uncertainty and extremism: Identification with high entitativity groups under conditions of uncertainty. In V. Y. Yzerbyt, C. M. Judd, & O. Corneille (Eds.), The psychology of group perception: Perceived variability, entitativity, and essentialism (pp. 401–418). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Horowitz, D. L. (2000). Ethnic groups in conflict. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

IAM. (2011, August 22). Israel-Academia-Monitor website. Retrieved from http://www.israel-academia-monitor.com/index.php?new_lang=en and http://faculty.biu.ac.il/~steing/policy%20PDFs/monitor_political_role.pdf

Isen, A. M. (1990). The influence of positive and negative affect on cognitive organization: Some implications for development. In N. L. Stein, B. Leventhal, & T. Trabasso (Eds.), Psychological and biological approaches to emotion (pp. 75–94). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Jarymowicz, M. (1997). Questions about the nature of emotions: On unconscious and not spontaneous emotions. Czasopismo Psychologiczne, 3(3), 153–170 (in Polish).

Jarymowicz, M., & Bar-Tal, D. (2006). The dominance of fear over hope in the life of individuals and collectives. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36, 367–392.

Jost, J. T. (2006). The end of the end of ideology. American Psychologist, 61, 651–670.

Jost, J. T., Federico, C. M., & Napier, J. L. (2009). Political ideology: Its structure, functions and elective affinities. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 307–337.

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W., & Sulloway, F. J. (2003). Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 339–375.

Kelman, H. C. (1958). Compliance, identification, and internalization: Three processes of attitude change. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2, 51–60.

Kelman, H. C. (1961). Processes of opinion change. Public Opinion Queerly, 25, 57–78.

Kelman, H. C., & Fisher, R. J. (2003). Conflict analysis and resolution. In D. O. Sears, L. Huddy, & R. Jervis (Eds.), Oxford handbook of political psychology (pp. 315–353). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Kelman, H. C. (2007). Social-psychological dimensions of international conflict. In I. W. Zartman (Ed.), Peacemaking in international conflict: Methods and techniques (pp. 61–107). Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press. Revised edition.

Kimball, C. (2002). When religion becomes evil. San Francisco, CA: Harper Collins Publishers.

Klar, Y. (2011, August). Barriers and prospects in Israel and Palestine: An experimental social psychology perspective. Paper presented in the Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA.