Abstract

Career-related parental support plays an important role in career adaptability. However, the condition and mechanism of parental career-related support on four dimensions of career adaptability are little known. Guided by the social cognitive career theory, positive psychological capital theory, and career construction theory, the current study investigates resilience and hope as two potential mediators between career-related parental support and different aspects of career adaptability. A sample of 636 vocational high school students responded to this study. The results indicated that: (a) students who often discussed future career plans with their parents had a higher level of career concern, career control, career curiosity, and career confidence than those who occasionally or never discussed future career plans; (b) career-related parental support positively related to the four dimensions of career adaptability; (c) parental career-related support was associated with more resilience, which related to a higher level of hope; ultimately, more hope related to higher career adaptabilities (i.e., career concern, career control, career curiosity, and career confidence); (d) parental career-related support related to different aspects of career adaptability through indirect pathways by more resilience or more hope. These findings advise educators to give various career-related support and pertinent career training to vocational high school students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Vocational school students will inevitably be an important part of the global labor market (United workers of the world, 2012). In China, one of the world’s largest manufacturing countries, there are 9865 vocational high schools with 16,281,400 in-school students by 2020 (MOE of PRC, 2021). However, because of some historical and cultural reasons, the degree of social recognition to vocational education is lower than other forms of higher education (Ling et al., 2021). Vocational high school students are often mentioned as those who perform poorly in academics and fail to elect to regular high school (Xu & Chen, 2016). They are in the transition from youth to adulthood, aged from 16 to 22 (Zhang et al., 2015). Due to academic failure and lack of motivation, vocational high school students are more susceptible to problem behaviors and mental health than those in regular high school (Pan et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2017). Moreover, vocational high school students have low career adaptability, which leads to employment risks and pressure on career development (Mei, 2021; Xiao et al., 2021). To improve the quality of the workforce, students’ career development is regarded as one of the most appropriate ways (Zhang et al., 2015). Most studies concerning career adaptability have predominantly focused on regular school students and undergraduates in Chinese contexts (Guan et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2015), with little attention paid to vocational school students. Therefore, it is urgent to investigate the mechanism and conditions for improving vocational high school students’ career adaptability.

Career adaptability has been widely recognized as a psychosocial resource in fitting career disequilibrium and transition (Savickas, 2005). It is crucial in career construction and consists of four different competencies (Savickas, 2005): career concern (prepare for long-term development, e.g., realizing today’s choices will shape the future), control (plan and act on work, e.g., making decisions by oneself), curiosity (explore the professional world, e.g., looking for opportunities), and confidence (accomplish the work and deal with career barriers, e.g., performing tasks efficiently). According to career construction theory, the four components of career adaptability have a dynamic and interactive effect on career development (Savickas, 2005; Zacher, 2014). Individuals’ different aspects of career adaptability may not develop in the same way (Liang et al., 2020). Previous studies concerning the four dimensions of career adaptability have primarily focused on two aspects: the prediction of career adapting response (such as proactive skill development, career planning, career engagement, and occupational self-efficacy; e.g. Hirschi et al., 2015; Taber & Blankemeyer, 2015; Nilforooshan & Salimi, 2016); the prediction of career adaptation results (such as life satisfaction, mental health, and satisfaction with school experience; e.g. Wilkins et al., 2014; Rivera et al., 2021). However, research on what conditions may influence the four competencies of career adaptability is not yet mature and well developed (Hlad’o et al., 2020).

There are, of course, many different factors contributing to students’ career adaptability when taking it as a whole variable. According to previous research and theory, these factors are mainly attributed to demographics, proactive personality, and social support factors. Among them, demographic factors refer to gender, age, ethnic background, and economical status (Guan et al., 2016; Hirschi, 2009). Proactive personality factors are important predictors of career adaptability, such as personality traits (Li et al., 2015) and goal-orientation (Creed et al., 2009). Social support factors (such as families, peers, and significant others) are associated with career adaptability (Hui et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2015). However, most researchers generally take career adaptability as a whole variable (Zhang et al., 2021; Guan et al., 2016), while few studies investigate different aspects of it (Rivera et al., 2021). Additionally, prior studies focus more on the influence of a single factor on career adaptability, but do not take the interactive and dynamic effects of these factors into consideration (Feng et al., 2021). Furthermore, parents are essential components for youths’ positive development and mental health, especially for the youths who are in the transition stage (Pollack, 2004), while little work is done about how parental support influence the different component of youth’s career adaptability. The impact of parents’ educational strategies on children needs to be comprehended in a cultural context (Tudge, 2008). For example, Chinese parents are more likely to take a more restrictive and controlling educational practice (Liu & Guo, 2010). Therefore, a more comprehensive and dynamic perspective is needed to explore the mechanisms of how career-related parental support promotes four competencies of career adaptability.

According to social cognitive career theory, the current study provides a perspective to fill the above limitations. Social cognitive career theory has taken career development as a dynamic process, which is affected by both individuals and contextual factors (Lent et al., 1994, 2000). Career behaviors are shaped by individuals’ cognition, such as self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and goals (Rogers & Creed, 2011). In addition, social cognitive career theory has proposed that environmental supports (e.g., financial support from the family) influence the development of career paths (Međugorac et al., 2020). Actually, career-related parental support is usually the primary contextual factor in promoting adolescents to pursue their career paths (Zhang et al., 2015). Based on social cognitive career theory, social contexts play an essential role in individuals’ cognitive factors, which in turn exert influence on career development (Gushue & Whitson, 2006). Resilience and hope are positive psychological capacities, which promote better career performance (Luthans et al., 2004). The two psychological capacities both have positive cognitive components. All in all, the current study assumes that the contextual factors of career-related parental support may be associated with resilience and hope and, consequently, with the development of four competencies of career adaptability. This study adds value to the extant literature in three ways. First, it offers a novel view on distinguishing the four competencies of career adaptability and tests its applicability to vocational school students. Second, compared with previous studies, this study explores the influencing factors of four components of career adaptability from a more comprehensive perspective in terms of demographics, personality traits, and social support. Third, the current study extends the social cognitive career theory by combing with positive psychological capital theory and career construction theory, and evaluates resilience and hope as two potential mediators between environmental supports (i.e. career-related parental support) and four dimensions of career adaptability. From a practical point of view, the current study enables educators to obtain targeted advice on promoting pertinent career training and educational approaches.

Career-related parental support and Career Adaptability

Career-related parental support refers to the educational and career-related development support provided by parents (Turner et al., 2003). According to the learning sources of self-efficacy constructed by Bandura (1977), there are four main resources of parental support influencing individuals’ self-efficacy: instrumental assistance, career-related modeling, verbal encouragement, and emotional support (Turner et al., 2003). Career-related support from parents has been conceived to be of great importance for individuals’ self-efficacy, career decision-making, and career development (Zhang et al., 2015). When having parental career-related support (e.g., parents provide necessary resources and stimulate their children to pursue their goals), adolescents tend to be more motivated, engage more in the process of career exploration, and set clearer career goals (Dietrich & Kracke, 2009; Ginevra et al., 2015). Previous studies showed that career-related support from parents would promote career maturity, career exploration, and career expectation of vocational students (Alfianto et al., 2019; Dietrich & Kracke, 2009; Zhang et al., 2015).

The social cognitive career theory framework (Lent et al., 1994) has taken the choices of career development as a dynamic process affected by both individual and environmental factors. Career goals, career interests, and career decision-making are not only influenced by individuals’ cognition and experiences, but affected by contextual factors, such as social support (Međugorac et al., 2020). Perceived social support enhances confidence in the process of career decision-making and promotes career adaptability skills (Ebenehi et al., 2016; Hlad’o et al., 2020). Particularly, prior studies indicated that support from parents was highly correlated with adolescents’ career decision-making (Turner et al., 2003) and career adaptability (Guan et al., 2016; Shulman et al., 2014). Furthermore, based on the attachment theory, when adolescents feel secure in their relationship with their parents, they are more likely to ask for guidance from their parents (Simões et al., 2016) and actively explore their future careers (Blustein et al., 1995). Career-related parental support is also an important predictor of career adaptability (Guan et al., 2016). Research have found the different mechanisms among four dimensions of career adaptability (Ebenehi et al., 2016; Hlad’o et al., 2020; Wilkins et al., 2014). However, previous research mostly took career adaptability as a whole variable (Alfianto et al., 2019; Guan et al., 2016; Shulman et al., 2014), in-depth exploration of the impact of career-related parental support on various aspects of career adaptability (i.e., career concern, career control, career curiosity, and career confidence) is rarely conducted. Thus, in this study, how career-related parental support affects four aspects of career adaptability will be investigated to further understand the role of parental career-related support in vocational high school student’s career adaptability, which enables parents to obtain practical advice on education and the promotion the career adaptability of their children.

Mediating roles of Resilience and Hope

Resilience has been recognized as the capacity of an individual to adapt to adversity and challenge (Luthar, 2000). When facing stress and hardship, people with more resilience can better deal with various difficulties and bounce back from setbacks (Mandleco & Perry, 2000; Smith, 2006). Further, resilience has not only been found as the major factor against depression, but positively associated with academic performance, career development, and life satisfaction (Buyukgoze-Kavas, 2016; Karaman et al., 2020). Thus, it is necessary to identify the factors promoting resilience. Rutter (1979) argues that family is one of the predictors of resilience. Adolescents with more parental involvement and support tend to have a higher psychological adjustment (Tubman & Lerner, 1994). Receiving more support from parents may be a particularly motivator to adolescents’ resilience. Besides, hope is a positive motivational state based on a cognitive set consisting of thoughts and pathways to pursue success and reach goals (Snyder, 2000). Parental involvement and support positively relate to adolescents’ goal setting and future plans (Ginevra et al., 2015). When encountering troublesome events, hopeful individuals will take difficulties as challenges (Paul, 2000). Hopeful students tend to perform better in career adaptation (Buyukgoze-Kavas, 2016). Increasing evidence shows that hope is not only related to positive career decidedness, career planning, and job outcome (Hirschi, 2014; Santilli et al., 2017), but facilitates individuals’ well-being (Yang et al., 2016).

The positive psychological capital theory has suggested that confidence, hope, optimism, and resilience are the four positive psychological capacities, which are found to be interactive and synergistic (Zubair & Kamal, 2015). All positive psychological capacities can be managed for better work performance (Luthans et al., 2004). Most prior studies examining positive psychological capacities have found that these capacities were associated with work attitude, employee creativity, and career success (Alessandri et al., 2018; Newman et al., 2018). Additionally, based on career construction theory (Savickas, 2005), hope is the proactive factor of adaptive readiness. Particularly, hopeful people tend to have more adaptability resources such as career concern, control, curiosity, and confidence (Cristina et al., 2016). Previous studies have suggested that individuals who report higher levels of psychological resilience tend to be more hopeful (Çelik et al., 2015; Karaman et al., 2020). The reason is that resilient adolescents would plan for the future and achieve their goals with more ambition (Everall et al., 2006). Hope can mediate the link between resilience and subjective well-being (Satici, 2016), and life satisfaction (Karaman et al., 2020). However, a few inconsistent findings show that more hopeful people report higher resilience (Jones, 2015; Munoz et al., 2017). These somewhat inconsistent studies highlight the need for investigating the relationship between resilience and hope, and suggest that there may be a potential mediator (i.e., resilience and hope) between career-related parental support and career adaptability (i.e., career concern, career control, career curiosity, and career confidence). Career-related parental support will associate with more resilience, and subsequently, more resilience may relate to higher levels of hope, which may, in turn, increase the four dimensions of career adaptability.

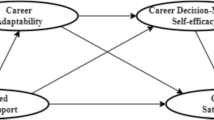

The current study

The present study is designed to examine the mechanisms and conditions of career-related parental support related to career adaptabilities (i.e., career concern, control, curiosity, and confidence) among a sample of Chinese vocational high school students. This study has two specific questions. First, does career-related parental support link with the four dimensions of career adaptability (i.e., career concern, control, curiosity, and confidence)? It is expected that parental career-related support relates to the four dimensions of career adaptability under the guidance of the social cognitive career theory framework (Lent et al., 1994) and attachment theory (Simões et al., 2016). Second, do resilience and/or hope mediate the link from career-related parental support to the four dimensions of career adaptability? It is hypothesized that parental career-related support will relate to more resilience; and more resilience will associate with higher levels of hope, which in turn, will promote more career adaptabilities (i.e., career concern, control, curiosity, and confidence). Moreover, a positive indirect effect would be found from career-related support to resilience/hope to career adaptabilities. The above conditions and mechanisms may be different in the four dimensions of career adaptability. The conceptual structure model is presented in Fig. 1.

Materials and methods

Participants and Procedure

Research data is obtained from both field surveys and online investigations. The field survey was administrated by school psychologists to randomly distribute to the classroom of secondary vocational students from Guangdong province in China. Then a total of 115 valid data (81.56% of efficiency) were retrieved (measurements were taken from December 2021 to 10 January 2022). The abnormal answers and repeated selection of the same option were excluded. Other participants were given equal opportunities recruited through the contact networks of WeChat with the help of online fliers. The online investigation was conducted by randomly selecting 521 (59.48% of efficiency) secondary vocational students who answered questions in more than 3 min from Guangdong and Hebei province with a popular Chinese professional investigation website Wenjuanxing (www.sojump.com; measurements were taken from 21 to 2021 to 19 January 2022). The age of 636 participants ranged from 14 to 21(M = 16.33; SD = 0.91; 1.6% of participants did not report), including 50.8% male and 48.7% female (0.5% of participants did not report). In the current sample, 68% of the fathers had a junior high school degree or below, 25.6% of the fathers graduated from high school or secondary vocational school; 3.5% of the fathers graduated from college (3-year college), 2.0% of the fathers had a graduate degree. The proportion of mothers with education below junior high school was 72.5%, in high school or secondary vocational school was 22.2%, in college (3-year college) was 3.1%, in university was 1.3%. Every respondent participated voluntarily and was provided informed consent.

Measures

Career-Related parental support

Career-related parental behaviors questionnaire (PCB, Dietrich & Kracke, 2009; Guan et al., 2015) consists of 15 items assessing three parental behaviors in career choices, namely parental career-related support, parental career-related interference, and parental career-related lack of engagement. In the present study, we use only 5 items of the subscale of parental career-related support (e.g., “My parents encourage me to seek information about the vocations I am interested in.”). Career-related parental support describes the situation where there is no interference and neglect for their children’s own choices. Parents provide instrumental support and guidance when children needed help. The participants answered on a Likert 5-point scale from completely disagree (= 1) to completely agree (= 5). Previous research approved that the Career-related parental support subscale is of good reliability among the Chinese sample (Guan et al., 2015). The current study’s data has good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90).

Resilience

Resilience is assessed using the brief resilience scale (BRS) developed by Smith et al., (2008), evaluating the rebound ability from stressful events. The six items (e.g., I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times) on the scale are rated from does not describe me at all (= 1) to describes me very well (= 5) on a Likert 5-point scale, with a higher score indicating higher levels of resilience. Previous research supported BRS’s good reliability in the Chinese sample (Yu et al., 2022). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha is 0.57.

Hope

The hope scale (Snyder et al., 1997), an 8-item self-report scale, is used to assess the hopeful thinking of individuals, which consists of two subscales with 8 items: 4 to assess pathways thinking (e.g., I can think of many ways to get the things in life that are most important to me), and 4 to assess agency thinking (e.g., I think the things I have done in the past will help me in the future). Participants rated each item from not like me at all (= 1) to like me very much (= 5) on a Likert 5-point scale. A higher score indicates a more positive attitude towards the future. Hope scale has been adapted and validated among the Chinese sample and showed high internal consistency (Jiang et al., 2020). The Cronbach’s alpha in this study is 0.90.

Career Adaptability

Career adaptability is assessed by the 24-items of the Career Adaptability Scale (Savickas & Porfeli, 2012), which consists of four subscales: career concern, career control, career curiosity, and career confidence.

First, career concern involves 6 items (e.g., Realizing that today’s choices shape my future) assessing the level of individuals’ concerns about their vocational future. Items are rated from not strongest (= 1) to strongest (= 5) on a Likert 5-point scale. A higher score indicates a higher level of career concern. The subscale showed good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha is 0.90).

Second, career control refers to one’s ability to plan and act on their studies and work. 6 items (e.g., Making decisions by myself.) on the subscale are rated from not strongest (= 1) to strongest (= 5) under a Likert 5-point scale. Cronbach’s alpha is 0.91.

Third, career curiosity is used to assess curiosity about the professional world with 6 items (e.g., Looking for opportunities to grow as a person.). Under a Likert 5-point scale, items are rated from not strongest (= 1) to strongest (= 5). Cronbach’s alpha is 0.90.

Fourth, career confidence is to assess an individual’s confidence to accomplish what might come in their work. Using 6 items (e.g., Performing tasks efficiently.), rating from not strongest (= 1) to strongest (= 5) under a Likert 5-point scale to evaluate their career confidence. The Cronbach’s alpha is 0.95. Previous research has demonstrated career adaptability scale has excellent validity and reliability (Leung & Cheng, 2021). In the present study, the career adaptability Cronbach’s alpha is 0.97.

Data analyses

SPSS 26.0 and Mplus 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 2019) are applied for data analysis. There are three sets of analyses for comprehensive mediation mechanisms. First, to explore the impact of discussing future career plans (e.g., never, occasionally, or often) with the parents on vocational high school student s’ career adaptability, the current student uses ANOVA to analyze the relationship between the child talking about future career to parent and four dependent variables: career concern, career control, career curiosity, and career confidence. Second, using the Pearson correlation test to analyze the correlations among all variables. Third, mediation results (confirmed by 95% confidence intervals) are calculated by using bias-corrected nonparametric bootstrap with 5000 bootstrap samples (Pituch & Stapleton, 2008; Mallinckrodt et al., 2006; Preacher & Hayes, 2008). To evaluate the goodness of model fit with several indices: root means square error of approximation (RMSEA); standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR); Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and comparative fit index (CFI). Standard criteria used were as follows: RMSEA < 0.08; SRMR ≤ 0.10; TLI and CFI ≥ 0.90, which suggested an acceptable fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1992).

Results

Descriptive statistics

The differences in four dimensions of career adaptability (career concern, career control, career curiosity, and career confidence) across the three conditions of discussing future career plans with parents (never, occasionally, often) were tested via one-way ANOVA. The means and standard deviations of groups are presented in Table 1. Participants were significantly different on: (1) career concern F(2, 624) = 38.49, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.11; (2) career control F(2, 629) = 19.74, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.06; (3) career curiosity F(2, 629) = 27.28, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.08; (4) career confidence F(2, 629) = 18.80, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.04. Moreover, post hoc results showed that students who often discussed future career plans with their parents had a higher level of the four dimensions of career adaptability(career concern, career control, career curiosity, and career confidence) than those who discussed future career plans with their parents never or occasionally, p < 0.001; students discussed their future career plans with their parents occasionally had a higher level for the four dimensions of career adaptability than students never discussed plans with parents, p < 0.01. Consequently, the impact of discussing career plans with parents was considered for the following mediation analysis.

Correlations analysis

Table 2 displays the mean, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations among study variables. Pearson correlations indicated that career-related parental support positively related to career concern, career control, career curiosity, and career confidence (r = 0.43 to 0.46, p < 0.001); career-related parental support, resilience, and hope were positively associated with each other (r = 0.27 to 0.63, p < 0.001); resilience and hope exerted significant effects on career concern, career control, career curiosity and career confidence (r = 0.24 to 0.61, p < 0.001).

Mediating Effects of Resilience and Hope

The mediation model included the following variables: the predictor variable (career-related parental support), the mediating variables (resilience and hope), and the outcome variables (career concern, control, curiosity, and confidence). All hypothesis paths were tested among the samples of vocational high school students (N = 636). This model had taken gender, discussing future career plans with parents, parental educational level, and family income as control variables. The mediation model concerning all paths was tested as depicted in Fig. 1, conducted with Mplus 8.3. The mediation model with standardized path coefficient values is shown in Fig. 2. The results indicated that the model fitted the data well: χ²(10) = 30.80; p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.06, 90%CI[0.04, 0.08]; SRMR = 0.03; TLI = 0.96 and CFI = 0.99.

All the direct and indirect effects were presented in Table 3. There were two significant indirect pathways linking career-related parental support to career concern: (1) vocational high school students with higher career-related parental support related to more hope, which in turn, were positively related to more career concern (β = 0.29, SE = 0.03, and 95%CI[0.24, 0.36]); (2) students with higher career-related parental support had more resilience, which related to more hope; ultimately, more hope was related to more career concern (β = 0.03, SE = 0.01, and 95%CI[0.02, 0.05]). However, the direct effect of career-related parental support to career concern was not accepted (β = 0.06, SE = 0.05, and 95%CI[-0.05, 0.16]), and the path for the link from career-related parental support to resilience to career concern was not significant (β = 0.00, SE = 0.01, and 95%CI[-0.02, -0.03]).

Similarly, there were two significant indirect pathways linking career-related parental support to career curiosity, which were the same as the linking form for the career-related parental support to career concern (details see Table 3).

The links from career-related parental support to career control were significantly mediated by resilience and hope. First, career-related parental support was positively related to resilience, which in turn, related to more career control (β = 0.04, SE = 0.01, and 95%CI[0.02, 0.07]).Second, hope was a significant mediator of the relationship between career-related parental support and career control (β = 0.26, SE = 0.30, and 95%CI[0.20, 0.33]). Third, career-related parental support had a positive impact on career control mediating by hope and resilience successively (β = 0.03, SE = 0.01, and 95%CI[0.02, 0.05]). However, the direct link of career-related parental support to career control was not accepted (β = 0.09, SE = 0.05, and 95% CI[-0.01, 0.18]).

Similarly, there were two significant indirect pathways linking career-related parental support to career confidence, which were the same as the linking form for the career-related parental support to career control (details see Table 3). However, the direct link of career-related parental support to career confidence was significant (β = 0.10, SE = 0.05, and 95% CI[0.00, 0.19]).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore the conditions and mechanisms of the four components of career adaptability in the process of interactions with environment support (i.e. career-related parental support). Guided by the social cognitive career theory (Lent et al., 1994, 2000), positive psychological capital theory (Luthans et al., 2004), and career construction theory (Savickas, 2005), the results suggested that parental career-related support had a positive effect on all aspects of career adaptability through indirect pathways. That is, resilience and hope mediated the relationship between career-related parental support and the four dimensions of career adaptability. These results are in line with previous studies which demonstrated that adolescents with career-related parental support tended to be more successful in career development (Dietrich & Kracke, 2009; Zhang et al., 2015).

Following the expectations, career-related parental support is positively associated with career concern, control, curiosity, and confidence. Moving beyond the prior studies (Dietrich & Kracke, 2009; Zhang et al., 2015), the findings suggest that students who often discuss future career plans with their parents have a higher level for the four dimensions of career adaptability, than those who discuss occasionally or never. However, career-related support from parents only has a direct effect on career confidence. This phenomenon can be explained by the four learning sources of self-efficacy constructed by Bandura (1977), career-related modeling resources of parental support influence self-efficacy (Turner et al., 2003). Specifically, adolescents with parental career-related support will have more career confidence to fit career disequilibrium and transition. Most prior studies have taken career adaptability as a whole variable (Alfianto et al., 2019; Guan et al., 2016), overlooking the difference among four aspects of career adaptability (Hlad’o et al., 2020; Wilkins et al., 2014). Moreover, previous researches mainly focus on how four aspects of career adaptability predict career adapting responses and adaptation results (e.g., Hirschi et al., 2015; Taber & Blankemeyer, 2015; Nilforooshan & Salimi, 2016), while the explanations of what and how the environmental factors influencing four dimensions of career adaptability have not well developed. Parents are essential components for positive youth development and mental health, especially for the youth who are in the transition stage (Pollack, 2004). In line with the social cognitive career theory (Lent et al., 1994, 2000), parental career support, as an environmental factor, will influence an individual’s career experiences. Parental career-related support (e.g., instrumental assistance, career-related modeling, verbal encouragement, and emotional support) allows adolescents to be concerned about their careers and cultivate more curiosity about their career paths early.

There are other important findings in the present study. This study illustrated the conditions and mechanisms through which career-related parental support influenced the four dimensions of career adaptability by identifying resilience and hope as potential mediators. First, parental career-related support related to more resilience, which was associated with a higher level of hope; ultimately, more hope related to greater career concern, career control, career curiosity, and career confidence. Based on social cognitive career theory, social contexts play an essential role in individuals’ cognitive factors, which in turn exert influence on career development (Gushue & Whitson, 2006). Parental involvement and support are vital to promoting adolescents’ resilience and hope (Tubman & Lerne, 1994; Ginevra et al., 2015). Resilience and hope are two interactive and synergistic positive psychological capacities, which both have positive cognitive components and are vital to better career performance (Luthans et al., 2004; Zubair & Kamal, 2015). Both of them can be managed for better work performance, such as employee creativity and career success (Luthans et al., 2004; Newman et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2019). Second, the research also suggested that students with parental career-related support would be more hopeful, which related to the four dimensions of career adaptability. Career construction theory has mentioned that hope is a proactive factor of adaptive readiness (Savickas, 2005). Hopeful individuals tend to have more adaptability resources such as career concern, control, curiosity, and confidence (Cristina et al., 2016). Third, parental career-related support positively related to resilience, which in turn, only related to more career control, and career confidence. Based on the attachment theory (Blustein et al., 1995), when adolescents feel secure with their parents, they are more likely to develop positive psychological factors and actively explore their future careers. Resilient adolescents will plan for the future and achieve their goals with more ambition (Everall et al., 2006). When facing stress and hardship, individuals with more resilience could better deal with various difficulties and bounce back from setbacks (Mandleco & Perry, 2000; Smith, 2006). Therefore, when vocational school students receive more career-related support from parents, they will have a high level of resilience. Then they are more positive to deal with various difficulties in career development and finally have more career control and confidence.

Theoretical contributions and implications for practice

The present study offered contributions to the literature in some aspects. First, it was interesting that the four components of career adaptability had different mechanisms. According to career construction theory (Savickas, 2005), career adaptability consists of four psychosocial resources (career concern, control, curiosity, and confidence). Additionally, the four components of career adaptability have a dynamic and interactive effect on career development (Zacher, 2014). However, early research on career adaptability often takes it as a whole variable (e.g., Guan et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2021), and mainly focuses on how it predicts career adapting responses and adaptation results (e.g., Hirschi et al., 2015; Taber & Blankemeyer, 2015; Nilforooshan & Salimi, 2016). Knowledge about what factors shape four components of career adaptability is limited. The current study extended the career construction theory and argued that it is especially important to distinguish the four dimensions of career adaptability. Second, this study contributed to the literature by providing evidence on the factors shaping four components of career adaptability. Results of this study have indicated that demographics, proactive personality and social support factors play joint roles in comprehensively and dynamically shaping the four competencies of career adaptability. This study particularly highlights the essential component of parental support in the career development of the youth. Third, this study extended the social cognitive career theory by combining with positive psychological capital theory and career construction theory, which reveals the specific conditions and mechanisms of the four dimensions of career adaptability in the process of interactions with the environment. Social contexts (i.e. career-related parental support) are essential to individuals’ cognitive factors, which in turn exerted influence on career development. Finally, this study tested its applicability to vocational school students, which contributed to the literature. The family especially parents attach great importance and high expectations to children’s career development in China (Liu et al., 2015). However, because of some historical and cultural reasons, the degree of recognition of vocational education is lower than in other forms of higher education in China (Ling et al., 2021). The attention to how parental career support shape career adaptability of vocational school students is limited. This study offered a novel view on career-related parental support promoting four components of career adaptability and enriching the development of vocational school students’ theory.

The research has some practice implications for educators. First, the current study has found that parental career-related support is vital for adolescents to find career paths and improve career adaptability, especially in career confidence. Parents can not only discuss some career-related topics with their child, but encourage the child to collect career information and participate in internship activities. Additionally, parental career-related support (e.g., instrumental assistance, career-related modeling, verbal encouragement, and emotional support) could begin when the child is in the junior high school stage. Career guidance counselors and schools also can provide career-related education training and counseling programs for parents. However, the training and counseling programs for parents may face some challenges in practice (Arfasa & Weldmeskel, 2020). To develop effective strategies, the school should consider providing parents with professional lectures and building home-school communication platforms. These strategies would help parents recognize the important role and get timely information in cultivating their child’s career adaptability. Second, there are four different competencies in career adaptability. According to a previous study, novel and innovative strategies were useful to stimulate students’ interest (Gamble & Crouse, 2020). For example, career games can be designed in software, which can make students aware of some future career challenges in advance. The important technique can be used to provide students with more career adaptability resources (i.e., career concern, career curiosity, career control, and career confidence). Third, vocational schools should consider cooperating and communicating with enterprises, which can create more job opportunities for vocational high school students. In addition, educational efforts should be made to enhance secondary vocational students’ positive psychological capacities, such as resilience and hope. Schools can develop a professional career guidance teacher team, who can provide positive psychological guidance to students. Moreover, teachers can organize career-planning programs, design and plan career courses for students, which allow adolescents to be concern about their careers and cultivate more curiosity about their career paths early. Although students may face unpredictable problems in career development, they can improve their career adaptability through these approaches to succeed in their career path.

Limitations and future directions

There are also some limitations, leaving opportunities for future research. First, this study uses self-reported measures. Although previous studies showed that the most reliable source of adolescents may come from their own experiences and feelings (Trompetter et al., 2017), it may still produce a common method bias. The current study has conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to test the degree of common method bias and found it was acceptable. To reduce the impact of common method bias, future studies are recommended to gather students’ information from parents, peers, or teachers. Second, this study is a cross-sectional design with a solid foundation of theories and empirical evidence. However, it is a common challenge to infer the causal relationship among variables with cross-sectional studies. Future researchers are advised to use at least three waves of data to replicate our study and better explore the relationship of all variables. Third, although this study is based on the social cognitive career theory framework (Lent et al., 1994), the current model investigated the causal relationship between career-related parental support and career adaptability. However, other forms of career-related support, such as teachers’ and peers’ support, need to be explored in future studies. Lastly, although the literature claimed the importance to focus on vocational school students, this study only collected the data from China. Some variables such as ethnicity or racial diversity were not taken into account. So future researchers can design and make a cross-cultural comparison.

Conclusions

Career-related parental support is a positive factor for career adaptability (career concern, control, curiosity, and confidence). Many prior studies on career adaptability have examined career adaptability as a whole factor while overlooking its different mechanisms. Moreover, the research on career-related parental support through what conditions relate to four competencies of career adaptability is limited. Guided by the social cognitive career theory (Lent et al., 1994, 2000), positive psychological capital theory (Luthans et al., 2004), and career construction theory (Savickas, 2005), the current research filled in these gaps by investigating the mediating roles of resilience and hope in the link between career-related parental support and four different aspects of career adaptability. The results indicated that students who often discussed future career plans with their parents had a higher level of the four competencies of career adaptability (career concern, control, curiosity, and confidence) than those who discussed future career plans with their parents occasionally or never. Besides, parental career-related support is associated with more resilience, which is related to a higher level of hope; ultimately, more hope is related to greater career adaptability (i.e., career concern, career control, career curiosity, and career confidence). Parental career-related support can relate to different aspects of career adaptability through more hope. Additionally, career-related parental support was positively related to resilience, which in turn, only related to more career control, and career confidence. These findings highlight the importance of distinguishing four competencies in career adaptability. These findings also suggest that it would be helpful for parents to provide various career-related support to children, which can enhance students’ positive psychological capacities (i.e., resilience and hope), and finally promote career adaptability.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the first authors, upon reasonable request.

References

Alessandri, G., Consiglio, C., Luthans, F., & Borgogni, L. (2018). Testing a dynamic model of the impact of psychological capital on work engagement and job performance. Career Development International, 23(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-11-2016-0210

Alfianto, I., Kamdi, W., Isnandar, & Dardiri, A. (2019). Parental support and career guidance as an effort to improve the career adaptability of vocational high school students. International Journal of Innovation Creativity and Change, 8(1), 163–173. https://www.ijicc.net/images/vol8iss1/8114_Alfianto_2019_E_R.pdf

Arfasa, A. J., & Weldmeskel, F. M. (2020). Practices and challenges of guidance and counseling services in secondary schools. Emerging Science Journal, 4(3), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.28991/esj-2020-01222

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Blustein, D. L., Prezioso, M. S., & Schultheiss, D. P. (1995). Attachment theory and career development: current status and future directions. The Counseling Psychologist, 23(3), 416–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000095233002

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 230–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124192021002005

Buyukgoze-Kavas, A. (2016). Predicting career adaptability from positive psychological traits. The Career Development Quarterly, 64(2), 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12045

Çelik, D. A., Çetin, F., & Tutkun, E. (2015). The role of proximal and distal resilience factors and locus of control in understanding hope, self-esteem and academic achievement among Turkish pre-adolescents. Current Psychology, 34(2), 321–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-014-9260-3

Creed, P. A., Fallon, T., & Hood, M. (2009). The relationship between career adaptability, person and situation variables, and career concerns in young adults. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(2), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.12.004

Cristina, M., Pallini, S., Maria, G., Nota, L., & Soresi, S. (2016). Future orientation and attitudes mediate career adaptability and decidedness. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 95(96), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.08.003

Dietrich, J., & Kracke, B. (2009). Career-specific parental behaviors in adolescents’ development. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(2), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.03.005

Ebenehi, A. S., Rashid, A. M., & Bakar, A. R. (2016). Predictors of career adaptability skill among higher education students in Nigeria. International Journal for Research in Vocational Education and Training (IJRVET), 3(3), 212-229. https://doi.org/10.13152/IJRVET.3.3.3

Everall, R. D., Altrows, K. J., & Paulson, B. L. (2006). Creating a future: A study of resilience in suicidal female adolescents. Journal of Counseling & Development, 84(4), 461–470. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2006.tb00430.x

Feng, Q., Chen, X., & Guo, Z. (2021). How does role accumulation enhance career adaptability? A dual mediation analysis. Current Psychology, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02304-3

Gamble, B., & Crouse, D. (2020). Strategies for supporting and building student resilience in Canadian secondary and post-secondary educational institutions. SciMedicine Journal, 2(2), 70–76. https://doi.org/10.28991/SciMedJ-2020-0202-4

Ginevra, M. C., Nota, L., & Ferrari, L. (2015). Parental support in adolescents’ career development: Parents’ and children’s perceptions. The Career Development Quarterly, 63(1), 2–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2015.00091.x

Guan, M., Capezio, A., Restubog, S. L. D., Read, S., Lajom, J. A. L., & Li, M. (2016). The role of traditionality in the relationships among parental support, career decision-making self-efficacy and career adaptability. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 94, 114–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.02.018

Guan, Y., Wang, F., Liu, H., Ji, Y., Jia, X., Fang, Z. … Li, C. (2015). Career-specific parental behaviors, career exploration and career adaptability: A three-wave investigation among Chinese undergraduates. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 86, 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.10.007

Gushue, G. V., & Whitson, M. L. (2006). The relationship among support, ethnic identity, career decision self-efficacy, and outcome expectations in African American high school students: Applying social cognitive career theory. Journal of Career Development, 33(2), 112–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845306293416

Hirschi, A. (2009). Career adaptability development in adolescence: Multiple predictors and effect on sense of power and life satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(2), 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.01.002

Hirschi, A. (2014). Hope as a resource for self-directed career management: Investigating mediating effects on proactive career behaviors and life and job satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 1495–1512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9488-x

Hirschi, A., Herrmann, A., & Keller, A. C. (2015). Career adaptivity, adaptability, and adapting: A conceptual and empirical investigation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 87, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.11.008

Hlad′o, P., Kvasková, L., Ježek, S., Hirschi, A., & Macek, P. (2020). Career adaptability and social support of vocational students leaving upper secondary school. Journal of Career Assessment, 28(3), https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072719884299

Hui, T., Yuen, M., & Chen, G. (2018). Career adaptability, self-esteem, and social support among Hong Kong University students. The Career Development Quarterly, 66(2), 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12118

Jiang, Y., Ren, Y., Zhu, J., & You, J. (2020). Gratitude and hope relate to adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: Mediation through self-compassion and family and school experiences. Current Psychology, 41(2), 935–942. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00624-4

Jones, G. F. H. (2015). The journey of hope on the road to resilience: Former residents’ experiences in child care facilities [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. University of Windsor.

Karaman, M. A., Vela, J. C., & Garcia, C. (2020). Do hope and meaning of life mediate resilience and life satisfaction among Latinx students? British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 48(5), 685–696. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2020.1760206

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45(1), 79–122. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (2000). Contextual supports and barriers to career choice: A social cognitive analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47, 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.47.1.36

Leung, S. A., Mo, J., & Cheng, Y. L. G. (2021). Interest and competence flexibility and decision-making difficulties: mediating role of career adaptability. The Career Development Quarterly, 69, 184–200. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12267

Ling, Y., Chung, S. J., & Wang, L. (2021). Research on the reform of management system of higher vocational education in China based on personality standard. Current Psychology, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01480-6

Li, Y., Guan, Y., Wang, F., Zhou, X., Guo, K., Jiang, P., Mo, Z., Li, Y., Fang, Z. (2015). Big-five personality and BIS/BAS traits as predictors of career exploration: The mediation role of career adaptability. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 89, 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.04.006

Liang, Y., Zhou, N., Dou, K., Cao, H., Li, J. B., Wu, Q. … Lin, Z. (2020). Career-related parental behaviors, adolescents’ consideration of future consequences, and career adaptability: A three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 67(2), 208. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000413

Liu, M., & Guo, F. (2010). Parenting practices and their relevance to child behaviors in Canada and China. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 51, 109–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00795.x

Liu, J., McMahon, M., & Watson, M. (2015). Parental influence on mainland Chinese children’s career aspirations: child and parental perspectives. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 15, 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-015-9291-9

Luthans, F., Luthans, K. W., & Luthans, B. C. (2004). Positive psychological capital: Beyond human and social capital. Business Horizons, 47(1), 45–50.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2003.11.007

Luthar, S. S. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00164

Mallinckrodt, B., Abraham, W. T., Wei, M., & Russell, D. W. (2006). Advances in testing the statistical significance of mediation effects. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(3), 372–378. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.372

Mandleco, B. L., & Perry, J. C. (2000). An organizational framework for conceptualizing resilience in children. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 13, 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.17446171.2000.tb00086.x

Međugorac, V., Šverko, I., & Babarović, T. (2020). Careers in sustainability: an application of social cognitive career theory. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 20(3), 477–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-019-09413-3

Mei, J. (2021). Investigation and Countermeasure Analysis of the Current Situation of Students’ Career Planning in Secondary Vocational Schools. Mental Health Education in Primary and Secondary School, 21(10), 27–29. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-2684.2021.10.009

MOE of PRC (2021, March 1). Major educational achievements in China in 2020. https://en.moe.gov.cn/features/2021TwoSessions/Reports/202103/t20210323_522026.html

Munoz, R. T., Brady, S., & Brown, V. (2017). The psychology of resilience: A model of the relationship of locus of control to hope among survivors of intimate partner violence. Traumatology, 23(1), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000102

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2019). Mplus 8.3. [computer software]. Los Angeles: CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Newman, A., Nielsen, I., Smyth, R., Hirst, G., & Kennedy, S. (2018). The effects of diversity climate on the work attitudes of refugee employees: The mediating role of psychological capital and moderating role of ethnic identity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 105, 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.09.005

Nilforooshan, P., & Salimi, S. (2016). Career adaptability as a mediator between personality and career engagement. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 94, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.02.010

Paul, K. (2000). Hope and dysphoria: The moderating role of defense mechanisms. Personality, 68(2), 199–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00095

Pan, Y., Yang, Z., Han, X., & Qi, S. (2021). Family functioning and mental health among secondary vocational students during the COVID-19 epidemic: A moderated mediation model. Personality and Individual Differences, 171, 110490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110490

Pituch, K. A., & Stapleton, L. M. (2008). The performance of methods to test upper-level mediation in the presence of nonnormal data. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 43(2), 237–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170802034844

Pollack, W. S. (2004). Parent-child connections: the essential component for positive youth development and mental health, safe communities, and academic achievement. New Directions for Youth Development, 103, 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.88

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.40.3.879

Rivera, M., Shapoval, V., & Medeiros, M. (2021). The relationship between career adaptability, hope, resilience, and life satisfaction for hospitality students in times of Covid-19. Journal of Hospitality Leisure Sport & Tourism Education, 29, 100344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2021.100344

Rogers, M. E., & Creed, P. A. (2011). A longitudinal examination of adolescent career planning and exploration using a social cognitive career theory framework. Journal of Adolescence, 34(1), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.12.010

Rutter, M. (1979). Protective factors in children’s responses to stress and disadvantage. Annals of the Academy of Medicine Singapore, 8(3), 324–338. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.113.6.e597

Santilli, S., Marcionetti, J., Rochat, S., Rossier, J., & Nota, L. (2017). Career adaptability, hope, optimism, and life satisfaction in Italian and Swiss adolescents. Journal of Career Development, 44(1), 62–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845316633793

Satici, S. A. (2016). Psychological vulnerability, resilience, and subjective well-being: The mediating role of hope. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.057

Savickas, M. L., & Porfeli, E. J. (2012). Career adapt-abilities scale: construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80, 661–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.011

Savickas, M. L. (2005). The theory and practice of career construction. In S. D. Brown, & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 42–70). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Shulman, S., Vasalampi, K., Barr, Z., Livne, Y., Nurmi, J. E., & Pratt, M. W. (2014). Typologies and precursors of career adaptability patterns among emerging adults: A seven-year longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescence, 37(8), 1505–1515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.06.003

Simões, E., Gamboa, V., & Paixão, O. (2016). Promoting parental support and vocational development of 8th grade students. Revista Brasileira de Orientacao Profissional, 17(1), 1–11. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=203049524002

Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972

Smith, T. W. (2006). Personality as risk and resilience in physical health. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(5), 227–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00441.x

Snyder, C. R., Hoza, B., Pelham, W. E., Rapoff, M., Ware, L., & Danovsky, M. (1997). The Development and validation of the children?s hope scale. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 22(3), 399-421. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/22.3.399

Snyder, C. (2000). The past and possible futures of hope. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19(1), 11–28. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2000.19.1.11

Taber, B. J., & Blankemeyer, M. (2015). Future work self and career adaptability in the prediction of proactive career behaviors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 86, 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.10.005

Trompetter, H. R., de Kleine, E., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2017). Why does positive mental health buffer against psychopathology? An exploratory study on self-compassion as a resilience mechanism and adaptive emotion regulation strategy. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 41(3), 459–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-016-9774-0

Tubman, J. G., & Lerner, R. M. (1994). Continuity and discontinuity in the affective experiences of parents and children: Evidence from the New York longitudinal study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 64(1), 112–125. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0079488

Turner, S. L., Alliman-Brissett, A., Lapan, R. T., Udipi, S., & Ergun, D. (2003). The career-related parent support scale. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 36(2), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2003.12069084

Tudge, J. R. H. (2008). The everyday lives of young children: Culture, class, and child rearing in diverse societies. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511499890

United workers of the world (2012). The Economist, 403, 83. http://www.economist.com/node/21556974

Wilkins, K. G., Santilli, S., Ferrari, L., Nota, L., Tracey, T. J. G., & Soresi, S. (2014). The relationship among positive emotional dispositions, career adaptability, and satisfaction in Italian high school students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(3), 329–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.08.004

Xu, Y., & Chen, X. (2016). Protection motivation theory and cigarette smoking among vocational high school students in China: a cusp catastrophe modeling analysis. Global Health Research and Policy, 1(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-016-0004-9

Xiao, Q. Y., Wei, R., & Chen, W. Y. (2021). Problems and countermeasures of career development of secondary vocational Students in the post-epidemic era. Education Science Forum, 35(30), 53–56. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1673-4289.2021.30.014

Yang, Y., Zhang, M. Y., & Kou, Y. (2016). Self-compassion and life satisfaction: The mediating role of hope. Personality and Individual Differences, 98, 91–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.086

Yu, X., Li, D., Tsai, C. H., & Wang, C. (2019). The role of psychological capital in employee creativity. Career Development International, 24(5), 420–437. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-04-2018-0103

Yu, Y., Yu, Y., & Hu, J. (2022). COVID-19 among Chinese high school graduates: Psychological distress, growth, meaning in life and resilience. Journal of Health Psychology, 27(5), 1057–1069. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105321990819

Zacher, H. (2014). Career adaptability predicts subjective career success above and beyond personality traits and core self-evaluations. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 84(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.10.002

Zhang, J., Yuen, M., & Chen, G. (2015). Career-related parental support for vocational school students in China. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 37(4), 346–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-015-9248-1

Zhang, J., Yuen, M., & Chen, G. (2021). Career-related parental support, vocational identity, and career adaptability: Interrelationships and gender differences. The Career Development Quarterly, 69(2), 130–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12254

Zhao, F., Zhang, Z. H., Bi, L., Wu, X. S., Wang, W. J., Li, Y. F., & Sun, Y. H. (2017). The association between life events and internet addiction among Chinese vocational school students: The mediating role of depression. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.057

Zubair, A., & Kamal, A. (2015). Work related flow, psychological capital, and creativity among employees of software houses. Psychological Studies, 60(3), 321–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-015-0330-x

Funding

This research was funded by the project of Postgraduate Research and Innovation Fund from School of Psychology, South China Normal University: “Research on Secondary Vocational Students’ Career Adaptability: Based on Career Construction Theory” (Grant Numbers: PSY-SCNU202136).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the local Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology, South China Normal University (SCNU-PSY-2022-041).

Author statement

Qing Zeng: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Review & Editing. Jia Li: Investigation, Literature review, Writing - Original Draft. Sijuan Huang: Investigation, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft. Jinqing Wang: Literature review, Writing - Original Draft. Feifei Huang: Writing - Review & Editing. Derong Kang: Literature review. Minqiang Zhang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, Q., Li, J., Huang, S. et al. How does career-related parental support enhance career adaptability: the multiple mediating roles of resilience and hope. Curr Psychol 42, 25193–25205 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03478-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03478-0