Abstract

We explore whether abusive supervision may occur more in mixed-race supervisor-subordinate dyads. Specifically, our model tests whether, in mixed-race dyads, a manager’s implicit racial bias may be associated with racial microaggressions, and, subsequently, subordinates’ perceptions of the degree to which that manager is an abusive supervisor. Social identity theory supports the why of these predictions. We also test when it may be possible for some managers to overcome their racial biases—by engaging in behaviors reflective of viewing their subordinates as individuals, rather than members of another race, via individuation theory. In this vein, we investigate a way in which race-based mistreatment and abusive supervision may be mitigated. We tested our predictions in 137 manager-employee dyads in two chemical manufacturing firms in South Africa. We found a positive relationship between manager implicit racial bias and abusive supervision, and that this relationship is lessened by individualized consideration–a moderator of the mediated effect of manager racial microaggressions on bias and abuse. Thus, our hypotheses were supported. We conclude with implications for victimized employees, and possible strategies to combat race-based aggression for organizations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Small signals that people from minority backgrounds are not welcome – such as ignoring them in meetings, not making eye contact and making no effort to pronounce a person’s name correctly – are rife in organizations…whether the perpetrators realize they’re doing it or not (B. Kandola in Wight, 2018).

Social movements such as Black Lives Matter in the United States and calls for expropriation of land from white farmers in South Africa (BusinessTech, 2018) bring attention to heated, contemporary race-based tensions in societies across the globe. And scholars are increasingly documenting the extent to which race affects workplace relationships and the underlying processes of race-based discrimination at work (Hirsh & Lyons, 2010). Post-Apartheid South Africa has experienced, and continues to experience, significant social, economic, and political transformation (Motsei & Nkomo, 2016), yet workplace equality, according to South Africa’s demographic makeup, remains unrealized (Nkomo, 2011). People in South African workplaces continue to report widespread discrimination, bias, and stereotyping (Nkomo, 2011). Victims of workplace mistreatment attribute this to social group membership, that is, ingroup-outgroup categorizations based on gender, race, religion, and education (Motsei & Nkomo, 2016). Today in South Africa, like in most countries, racism is more insidious and less explicit than in the past, often categorized not by outright expressions of bigotry, but by microaggressions, which are “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of color” (Sue et al., 2007, p. 271). Racism’s subtler forms include a lack of support or distrust of other-race colleagues, or instances of being “overlooked, underrespected, and devalued” because of one’s race (Sue et al., 2007, p. 273). Microaggressions are a form of discrimination not necessarily legally actionable as they include behaviors which fall outside legal protection such as being excluded from informal social events (Dhanani et al., 2017). These behaviors are pervasive and impair individual and organizational performance (Franklin, 2004). In fact, seventy-four percent of complaints to the South African Human Rights Commission are based on race, ethnicity, or social origin (South African Human Rights Commission, 2018). And in the UK, discrimination against black, Asian, and other minority ethnic groups costs the economy £ 2.6 billion per year (Centre for Economics and Business Research & Involve, 2018).

In the management literature, increasingly, general interpersonal mistreatment by one’s supervisor is being studied through the construct abusive supervision, that is, a subordinate’s perceptions of the extent to which his or her supervisor engages in “the sustained display of hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors, excluding physical contact” toward him or her over time (Tepper, 2000, p. 178). Abusive supervision differs from conceptually overlapping deviance-related constructs such as workplace aggression which includes the intention to harm either an individual in the organization or the organization itself (Hershcovis et al., 2007). It also differs from manager bullying and undermining where again there is an attempt to psychologically harm a follower. In the case of abusive supervision, what matters is the perception of abuse from the employee; the behavior may or may not be manager-intended (Martinko et al., 2013).

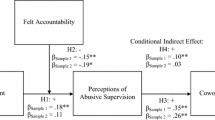

As Tepper (2007) relates, while management scholars have demonstrated a host of subordinate outcomes from experiencing abusive supervision, including emotional distress (Tepper et al., 2007), work group interpersonal deviance (Mawritz et al., 2012), work-family conflict (Tepper, 2000), and diminished self-esteem (Burton & Hoobler, 2006), we still know less about the factors that predict abusive supervision—the why and when of abusive supervision. Examples of supervisor characteristics that have been found to predict abusive supervision are their own depression (Tepper et al., 2006), their perceptions of injustice (Hoobler & Brass, 2006), and stress (Burton et al., 2012; Harris et al., 2011). In this study, we explore whether abusive supervision may occur more in mixed-race supervisor-subordinate dyads—specifically whether a manager’s negative implicit racial bias may be associated with their racial microaggressions, and, subsequently, subordinates’ perceptions of the degree to which that manager is an abusive supervisor. That is, we test whether racial microaggressions may be a linking mechanism between racial bias and employee perceptions of abusive supervision. Because bias- and stereotype-motivated behavior have moved from being overt, direct and hostile, to more subtle, ambiguous and sometimes unintentional (Ziegert & Hanges, 2005), it is now critical to understand if manager’s implicit bias could possibly predict these small acts of discriminatory behaviour that contribute to subordinates’ perceptions of abusive supervision at work. Tepper et al. (2011) found that managers may view some employees as worthy of just treatment, that is, within their scope of justice, but other employees as “expendable, undeserving, exploitable, and irrelevant” (Opotow & Weiss, 2000: 478), that is justifiable targets of abusive supervision. Social identity theory (e.g., Ashforth & Mael, 1989) supports the why of these predictions—that managers should feel less kinship and favor subordinates less who are racial outgroup members as compared to ingroup subordinates who are the same race as the manager. Subsequently, managers should engage in a greater number of racial microaggressions in mixed-race dyads, and perceptions of abusive supervision should be higher. On the other hand, we test when it may be possible for some managers to overcome their racial biases—by engaging in behaviors reflective of viewing their subordinates as individuals, rather than simply “others,” that is, members of another race. Specifically, we test individuation theory (e.g., Brewer et al., 1995) predictions. In mixed-race dyads, managers who engage in more individualized consideration, that is, managers who pay more individual attention to followers, focus on followers’ unique motivations, and see followers as a whole person rather than as a member of a group (Bass, 1985; Bass & Riggio, 2006), should be seen as engaging in lower microaggressions, and lower abusive supervision (see Fig. 1). In this vein, we investigate a way in which race-based micro-aggressions and abusive supervision may be mitigated. Our model tests whether, for mixed-race dyads, individualized consideration moderates the mediated relationship of racial microaggressions on the relation between race bias and abusive supervision. We tested our predictions in 137 manager-employee dyads in two chemical manufacturing firms in South Africa.

Our study makes several contributions to the literature. First, we add to the growing body of literature that seeks to uncover predictors of managers’ abusive supervision. We are the first to empirically document a potential race-based motivation behind the abusive supervision construct. We find evidence that manager implicit racial bias and employee evaluations of manager racial microaggressions and abusive supervision are related. Second, we test racial bias by using a modern, unconscious measure of implicit bias—a race-based implicit association test (IAT). Earlier scholarship using self-reported racism measures has been criticized, as these designs assume respondents can recognize racist beliefs within themselves and are willing to report on these behaviors honestly (Cunningham et al., 2001). Implicit association tests originated in the late 1990s to reveal the components of racial bias and other attitudes that fall outside of conscious control (Banaji et al., 2001). Third, we test an observable manifestation of implicit racial bias—racial microaggressions. Employees may not know of the unconscious biases of their managers, but these biases may be observed by employees as racial microaggressions. In this way, we attempt to demonstrate a way in which biases translate into observable workplace mistreatment that may contribute to employee abusive supervision perceptions. Fourth, while many studies on race in the workplace focus solely on documenting this insidious social problem, we take a step toward identifying a possible prevention factor: We find that one dimension of transformational leadership, individualized consideration, may lessen the impact of manager racial bias on follower outcomes. As a learned behavior, organizations may design interventions to promote managers’ individualized consideration, en route to not only more effective leadership, but as a way of stemming the impact of managers’ rather intractable racial biases on the treatment of their other-race employees (Bergh & Hoobler, 2018).

Theory and hypotheses

Social identity theory (SIT) and social categorization theory (SCT) have been popular ways of understanding and predicting behavior in organizations for at least 30 years. Stets and Burke (2000) state that social identity is formed through self-categorization and that this formation consists of two components, namely self-categorization and social comparison. Self-categorization results in an accentuation of similarities between the self and ingroup persons and an accentuation of differences between the self and outgroup members. Social categories used in forming social identity exist within a structured society that individuals are born into and only exist in relation to other contrasting categories: for example, black versus white, Christian versus Hindu, and male versus female. Each category has more or less power, prestige, and status. Social identity was described by Turner et al. (1994) as "the social categorical self (‘us’ versus ‘them;’ ingroup versus outgroup; us women, them men; us whites, them blacks…)" (p. 45). In summary, the term social identity refers to how individuals' sense of who they are is embedded in their membership of particular social groups, and, in comparison, not others (Hopkins & Reicher, 2011).

Important to our study, SIT is concerned with interpersonal situations, such as workplace relations, and argues that people work to maintain positive social group-based identities. SIT is a way of understanding the processes behind stereotyping because it theorizes how discriminatory intergroup relationships unfold (Tajfel, 1981). Social identity processes, specifically differences assumed to categorize outgroups, are a way that individuals justify negative behavior towards/mistreatment of outgroup members (Brown, 2000).

Abusive supervision is an employee’s perception of the degree to which his or her manager engages in workplace non-physical mistreatment toward the employee (Tepper, 2000). In general, an other-race employee should be more likely to view a manager who is higher on implicit racial bias, as compared to lower on implicit racial bias, more negatively. While some types of bias may be “under the radar screen” (Lee, 2012), studies of implicit bias find that even unconscious biases that people may attempt to control still “leak” to affect their visible behavior in various ways. Even people who express egalitarian beliefs and attempt to appear non-prejudiced toward blacks are prone to subtle racial discrimination as predicted by the IAT (Monteith et al., 2001). Theoretically, SIT predicts workplace mistreatment of others when those others are from a different race group from the aggressor. We hypothesize an effect congruent with social identity theory’s outgroup bias. When managers hold higher implicit racial bias, the observable manifestation of this bias may be racial microaggressions. Employees may not know of the unconscious biases of their managers, but these biases may be observed by employees as race-based slights, insults, and the like. When racial microaggressions happen frequently, we argue that employees may form an overall perception of supervisor mistreatment, that is, perceptions of abusive supervision. So biases translate into frequent, observable workplace microaggressions which may contribute to employee abusive supervision perceptions.

Individuation

Social identity and categorization theories predict categorical processing, that is, seeing other-race employees according to their race, and as outgroup members, as argued above. There is, however, evidence that many of the effects of group categorization of others may be offset if perceivers have sufficient motivation and ability to categorize others instead as individuals (Brewer, 1988; Fiske & Neuberg, 1990). While group categorization relies on the activation of pre-existing category associations and stereotypes, individuation, which is also called piecemeal processing, consists of paying attention to and contemplating unique features of a specific individual. The process of individuation allows the perceiver to move beyond stereotypical, category-based beliefs to focus more on the distinctive characteristics of an individual. In this way, individuating members of an outgroup can undermine outgroup biases (Ellemers et al., 1999).

Since the 1970s many scholars have studied positive leadership behavior as transformational leadership, that is, leaders who stimulate and inspire followers to achieve exceptional outcomes (Bass, 1985). One dimension of transformational leadership, individualized consideration (IC), maps well onto individuation theory. Bass theorized that IC is an important characteristic of a transformational leader. Leaders high in IC engage in behavior where they focus their attention on differences among followers and discover what motivates each employee. This individualized focus allows managers to become more familiar with each employee, should enhance communication, and improves downward and upward information exchange (Bass, 1985; Rafferty & Griffin, 2006). It is important to note that IC is not the same as what has been called color-blindness, the latter of which suggests that racial categories do not matter (Richeson & Nussbaum, 2004). Managers who are perceived by employees to be higher in individualized consideration are unlikely to ignore an employee’s race, as race has been shown to be one of the most salient social identity categories across societies (Booysen, 2007), and especially in South Africa, with its Apartheid past (Booysen, 2007). However, managers higher on IC see the whole person as an individual, inclusive of their intersecting identities and characteristics (Bass & Riggio, 2006). And higher IC managers are characterized by behavior such as individualized coaching and mentoring. They commonly guide and support employees using empowering behaviors that correspond with an employee’s particular needs, in a friendly, equal manner (Bass, 1985), and, we argue, despite the race category membership of the employee.

When managers engage in leadership behavior marked by individuation, that is, higher individualized consideration, this should allow them to see other-race employees not just as members of a racial outgroup, but as individuals, with their own characteristics including unique values, motivations, and human capital. When managers exhibit greater individualized consideration behavior, this can mitigate the impact of managers’ implicit racial biases on racial microaggressions and, downstream, employees’ perceptions of abusive supervision. While the literature on implicit bias shows that completely masking bias from others’ detection is often not possible for individuals (Lee, 2012), for managers who engage in positive, individuating behavior, their biases should result in fewer microaggressions and lower abuse perceptions. Because direct and overt discrimination is less tolerated in the workplace than in the past, implicit bias is more likely to manifest subtly today, in the form of workplace microaggressions. We argue that the observable manifestation of race bias is likely microaggressions, which predicts perceptions of abusive supervision. We therefore hypothesize a relationship where micro-level aggressive behaviors mediate the link between implicit racial bias of managers and abusive supervision, and individualized consideration qualifies the link between manager bias and employee detection of microaggressions.

Based on social identity theory, our theorizing applies just to ingroup-outgroup workplace relations. That is, we predict a moderating effect of individualized consideration on the mediated effect of microaggressions on implicit bias and abusive supervision, but just for mixed-race manager-employee dyads. When there are race-based social category differences, we hypothesize individualized consideration to be an ameliorating factor on employee outcomes. This pattern of relations depicted in Fig. 1 comprises a moderated moderated mediation effect (Hayes, 2018).

-

Hypothesis: For mixed-race dyads, individualized consideration moderates the mediated effect of manager racial microaggressions on the relation between manager implicit racial bias and abusive supervision such that the positive relation between manager implicit racial bias and abusive supervision is lessened.

Methodology

Sample and procedure

We collected data from managers and employees in two organizations in the chemical manufacturing industry, based in the province of Kwa-Zulu Natal, in South Africa. The Kwa-Zulu Natal population is largely dominated by African blacks, who constitute 87.2% of the total KZN population, followed by Indians at 7.2%, whites at 4.2% and colored or mixed-race persons, who make up the smallest percentage of the provincial population, at 1.4% (KZN Treasury, 2018).Footnote 1 The financial race-based demographics of KZN include an estimated 47.8% of African black persons in KZN who were categorized as low-income earners in 2015, in contrast to only 21.6% colored persons, 4.3% Indian persons, and 1% of white persons being low income (KZN Treasury, 2018). The sample for our study consisted of 137 dyads in total, of which 84 (61%) manager-employee dyads were dissimilar in terms of race. The sample was diverse from a racial perspective. The employee group consisted of 40.1% African blacks, 35% whites, 19.7% Indians, and 5.1% colored persons. Of the managers, 48.1% were white, 33.3% were Indian, and 18.5% were African black. The employee sample consisted of 77.4% males, and 79.6% of the managers were male, common to the chemical and manufacturing industries. The employee participants in our sample worked in an assortment of functions, including production, supply chain, engineering, agronomic services, health and safety, human resources, customer service, and finance roles. The sample of 137 dyads was comprised of 53 managers who were rated, on average, by 2.58 employees. The managers were responsible for an array of managerial responsibilities in their respective function, including directing and coordinating the activities of their subordinates, people-related tasks such as recruitment, development, and coaching of employees, monitoring of performance, planning, and managing department budgets, and preparation of reports. As far as the racial make-up of manager-employee dyads in the sample, for the same-race dyads, 42% were African blacks, 39% were Indians, and 33% were white.

To ensure the best possible response rate, a supervised data collection approach was followed which yielded a 98% response rate from the employee group, and a 98% completed IAT response rate from managers. Participants completed their surveys during normal working hours. The employees completed their paper-and-pencil surveys in a conference room, and the managers completed their computerized IAT tests in a boardroom, on laptops provided by the researchers. This procedure ensured that no technical challenges arose with the use of the IAT software and that managers were not distracted during the completion of the IAT, which requires concentration on the task at hand. The employee surveys contained measures of workplace racial microaggressions, abusive supervision, and individualized consideration. The managers completed a multicategory race IAT as described below.

Measures

Implicit racial bias

Managers’ implicit racial bias was measured using the Multicategory IAT (MC-IAT), which tests the automatic strength of associations between positive and negative evaluations, and four racial groups (African black, Indian, colored, and white). The MC-IAT consisted of 14 blocks, with the first two being practice blocks. In each block, managers must categorize items, presented to them one at a time, as quickly as possible. In the first block that consists of 16 trials, managers categorize the positive/good words (love, pleasant, great, and wonderful) by pressing the “I” key and the “E” key for negative/bad words (hate, unpleasant, awful and terrible). In the second block, consisting of 20 trials, managers categorize a specific racial group (African black, Indian, colored, and white) with good words (love, pleasant, great, and wonderful) using the “I” key, and for “anything else” they press the “E” key. For the further 12 blocks, the test design is similar, using a different combination of target and other race groups. The calculation of the bias score (D score) for each race category is based on the principle that individuals will faster and more accurately associate good/positive words with race categories that do not conflict with their own automatic biases (Rudman, 2011). Thus, when highly associated stimuli and evaluations are presented in the IAT, response times are expected to be swifter and more accurate than when less automatically associated stimuli and evaluations are presented (Hall et al., 2015). The D score for each race category is calculated according to the guidelines provided by Nosek et al. (2014). The MC-IAT produced six D scores, each representing a different combination of racial group contrasts (African black vs. white, African black vs. colored, African black vs. Indian, colored vs. Indian, Indian vs. white, colored vs. white). The D score is computed for each contrasting combination by subtracting the average response latency for one block (e.g., white categorized with good words, African black categorized with bad words) from the average response latency for the contrasting block (e.g., white categorized with bad words, African black categorized with good words), followed by dividing the standard deviation of the latencies across the two blocks. Finally, an aggregate D score for each racial category is calculated by aggregating the three other D scores, (e.g., the white score is the average of three D scores, i.e., white compared to African black, Indian, and colored people) (Axt et al., 2014). This analysis strategy provided four D scores that are interdependent, with the mean of the four scores always being 0. Scores that are greater than 0 (positive) indicate more positive or favorable implicit associations compared to the mean evaluation across the four racial categories. Scores that are below 0 (negative) indicate more negative or unfavorable implicit associations with the racial category than the mean evaluation across the four groups (Axt et al., 2014). The D score used in our analysis indicates the implicit bias of each manager against the race group that his/her direct report belongs to.

Racial microaggressions

Racial microaggressions was measured by using the Workplace and School Microaggressions subscale of the Racial and Ethnic Microaggressions Scale (REMS) (Nadal, 2011). The questionnaire asked employees to complete five items, using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (I did not experience this event in the past six months) to 5 (I experienced this event 10 or more times in the past six months), to ascertain the number of times that employees experienced each particular microaggression displayed by their manager during the past six months. To focus on workplace microaggressions enacted by managers, the items were adapted to exclude any reference to microaggressions experienced at school and to reflect the experience of managers' behavior. For example, “I was ignored at school or at work because of my race” was changed to “I was ignored by my manager at work because of my race.” The five items were averaged to compute one racial microaggressions score, reflecting an employee’s experience of workplace racial microaggressions by his or her manager (α = 0.95).

Abusive supervision

To measure abusive supervision, Tepper's (2000) 15-item abusive supervision scale was used. This scale asks participants to respond to 15 items on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (I cannot remember him/her using this behavior with me) to 5 (He/she uses this behavior very often with me), to evaluate the extent to which employees perceive their managers’ behavior as abusive. Example items include “blames me to save himself/herself embarrassment,” “puts me down in front of others,” and “tells me I’m incompetent.” The fifteen items were averaged to form an overall score reflecting abusive supervision (α = 0.94).

Individualized consideration

We used the individualized consideration (IC) factor subscale from the revised Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (Avolio & Bass, 1995)Footnote 2 to measure IC. Employees were asked to respond to four items using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (frequently, if not always). A sample item is: "My manager treats me as an individual rather than just a member of a group." We purposefully did not amend the wording of this scale to refer to race group. As we argued above via individuation theory, we theorize manager IC to include a holistic view of individual employees not limited to a particular social group categorization. The four items were averaged to form an overall score for IC (α = 0.78).

Analysis strategy

We used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to verify the factor structure of our measurement scales using AMOS 25.0 (Arbuckle, 2017). Overall model fit was assessed by the chi-square statistic (χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). CFI and IFI were appraised using the recognized value of 0.90 as an indication of good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). To test our hypothesis, we applied Model 11 of Hayes’ PROCESS procedure using version 3.0 in SPSS (Hayes, 2013), while controlling via dummy variable for the nesting effects of the two organizations in our sample. By examining the PROCESS output, we were able to make determinations about whether the moderation of the indirect effect of IC on the mediated relation between implicit bias and abusive supervision through racial microaggressions, is dependent on a second moderator, i.e., racial dissimilarity of dyads–-moderated moderated mediation (Hayes, 2018).

Results

Factor structure

We performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to determine the overall goodness-of-fit of the measurement model. The employee-rated manager behavior model, inclusive of microaggressions, abusive supervision, and individualized consideration, provided an inadequate fit to the data (CFI = 0.86). An examination of the modification indices revealed that fit could be improved if several items from the abusive supervision scale were allowed to correlate with the conceptually similar microaggressions factor. Microaggressions are employee perceptions of the frequency of discrete forms of mistreatment experienced over the past six months, attributed by the employee to be due to their race (e.g., my manager was unfriendly or unwelcoming toward me because of my race). Whereas, abusive supervision is an employee’s general sense of manager mistreatment, without an attribution as to why is it occurring. Hence, they are both behaviors performed by one’s manager, and the behaviors could overlap—some being attributed to race and others not. Hence, we correlated error terms from five items from the abusive supervision scale with the microaggressions factor. For example, abusive supervision item 3 (“My boss gives me the silent treatment”) could be considered conceptually similar to the number of times one is “overlooked” and “ignored” because of one’s race in the racial microaggressions scale. While we do not know whether the behaviors indicated in the abusive supervision scale were attributed by the employee to his or her race, this is a possibility, and a reason for potential construct overlap with the racial microaggressions scale. To acknowledge this, we added five covariances between error terms for these abusive supervision items (1—“My boss ridicules me,” 3—detailed above, 5—“My boss invades my privacy,” 10—“My boss expresses anger at me when he/she is mad for another reason,” and 11—“My boss makes negative comments about me to others”) and the microaggression factor. Model fit reached acceptable levels (CFI = 0.91, IFI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.08).

We then compared the fit of this model with an alternative model (see Table 1) where abusive supervision and racial microaggressions are treated as a single factor, with individualized consideration as a separate factor, to see if this alternative model might result in improved fit. The alternative model did not yield improved fit (CFI = 0.71, IFI = 0.72, RMSEA = 0.14). We tested a second alternative model where all three of the employee-rated manager behavior variables–abusive supervision, individualized consideration, and racial microaggressions–are treated as a single factor. The second alternative model also demonstrated poorer fit (CFI = 0.78, IFI = 0.76, RMSEA = 0.12) as compared to our original model, so we retained our original model which included the correlation between abusive supervision error terms and the microaggression factor. The results of the confirmatory factor analyses are presented in Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and the zero-order correlations appear in Table 2. Managers’ implicit racial bias correlated significantly with racial microaggressions (r = 0.20, p < 0.05), and abusive supervision (r = 0.20, p < 0.05). And a negative relationship was found between individualized consideration and racial microaggressions (r = -0.35, p < 0.01), and abusive supervision (r = -0.55, p < 0.01).

We began by exploring whether any of the sample demographics correlated with abusive supervision and racial microaggressions. As per previous studies (Zhang & Bednall, 2016), we found a significant relationship between employee gender and abusive supervision (r = -0.21, p < 0.05), which means that male subordinates reported higher abusive supervision. We also found a relationship between racial microaggressions and employees’ home language (r = -0.24, p < 0.01), meaning that employees who spoke languages most commonly associated with black ethnicity (isiZulu, isiXhosa, and Setswana) reported more frequent microaggressions, which is in line with our status-based social identity theorizing. No significant correlations were found between age, education, and the main constructs in the study. In addition, we calculated interclass correlations (ICC) and their confidence intervals using SPSS and a two-way random effect model with absolute agreement to explore crossemployee agreement on manager measures: individualized consideration, racial microaggressions, and abusive supervision (Bliese, 2000). A degree of reliability was found between employees rating the same manager based on group means. ICC(2) for individualized consideration was 0.753 with a 95% confidence interval from 0.678 to 0.814 (F (136,408) = 4.086, p = 0.000), indicating moderate agreement. Whereas, racial microaggressions was 0.946 with a 95% confidence interval from 0.930 to 0.960 (F (130,520) = 19.507, p = 0.000) and abusive supervision was 0.958 with a 95% confidence interval from 0.946 to 0.968 (F (136,408) = 25.192, p = 0.000). These ICCs are consistent with existing research showing multiple persons’ perceptions of a focal individual’s individualized consideration (e.g., Kim & Vandenberghe, 2018), microaggressions (e.g., Ellis et al., 2019), and abusive supervision (Mawritz et al., 2012) are often similar.

Hypothesis testing

We hypothesized that the moderation effect of individualized consideration on the indirect effect of manager implicit racial bias on abusive supervision through racial microaggressions, would be moderated by the racial dissimilarity of manager-employee dyads. To allow for the nested structure of our data, that is, the two organizations in our sample, we added a dummy variable, dummy coded 1 for the first organization and 2 for the second organization, as a control. We found that when managers are lower in individualized consideration, racial bias is more strongly related to racial microaggressions, such that higher individualized consideration reduces the positive relationship between implicit racial bias and racial microaggressions. Employees experience the most racial microaggressions when managers have higher racial bias and are lower in individualized consideration (β = 4.45, t = 2.27% CI [0.86, 8.04], p < 0.05). These findings are depicted in Fig. 2.

However, these findings reflect just the first stage of the mediation process. They do not explain the full model–the indirect effect of implicit racial bias on abusive supervision moderated by individualized consideration (W) and the racial composition of dyads (Z). This is reflected in Figs. 3 and Table 3. Probing the three-way interaction between implicit racial bias, individualized consideration, and racial dissimilarity of manager-employee dyads reveals that individualized consideration moderates the effect of implicit racial bias on abusive supervision through racial microaggressions for mixed-race dyads. When manager-employee dyads are racially dissimilar and individualized consideration is high (W = 3.25), the indirect effect of implicit racial bias on abusive supervision through racial microaggressions is negative (β = -0.414 CI [-1.03, -0.35], p < 0.001); but among same-race dyads, there appears to be no significant indirect effect of bias on abusive supervision through racial microaggressions (β = -0.01, CI [-0.15, 0.12], p = n.s.).

These results reflect moderated moderation mediation, that is, the moderation of the indirect effect of implicit racial bias by one moderator (IC) depends on the other moderator (racial dissimilarity of dyads). The index of moderated moderated mediation supports this in that the 95% bootstrap confidence interval does not include zero (0.044 to 1.215). Our hypothesis is supported.

To rule out other explanations for our theoretical model, we reran our test including many control variables. As shown in Table 3, we tested the effects of employee gender (male = 1 and female = 2), and employees’ home language (languages commonly associated with black ethnicities = 0 and languages commonly associated with whiteness = 1) as control variables. We found no significant differences when including these control variables.

Discussion

In a study of 137 manager-employee dyads in the chemical manufacturing industry in South Africa, we supported a model where manager racial bias is implicated in employee reports of abusive supervision. Tepper (2007) asks in his review of the abusive supervision literature the important question of what kinds of people and under what conditions, people are likely to become victims of abusive supervision (p. 267). One category of factors he delineates as antecedents to abusive supervision is supervisor characteristics. Beyond, for example, supervisor depression (Tepper et al., 2006), and stress (Burton et al., 2012; Harris et al., 2011), we add another supervisor precipitating factor, implicit racial bias. We found that manager implicit racial bias had indirect effects on employees’ perceptions of abusive supervision.

Theoretical contributions

We examined the link between implicit racial bias and abusive supervision from a social identity perspective—that managers would favor same-race employees and be more likely to aggress against outgroup, other-race employees due to ingroup bias. Our theoretical story links well to earlier work by Tepper et al. (2011) that approached abusive supervision from a moral exclusion perspective. They argued that, for various reasons including being dissimilar to the targets of their abuse, managers view some employees as worthy of just treatment, that is, within their scope of justice, but other employees as “expendable, undeserving, exploitable, and irrelevant” (Opotow & Weiss, 2000: 478). Employees who are excluded from moral treatment are therefore justifiable targets of abusive supervision. While Tepper and colleagues tested managers’ perceptions of deep-level dissimilarity with their subordinates (e.g., values, outlook, problem-solving styles), our study demonstrates that managers seem to also divide subordinates into justifiable targets versus non-targets of abusive supervision by surface-level demographic characteristics, specifically race. As mentioned earlier, work on the predictors of abusive supervision is in short supply (Mackey et al., 2017; Tepper, 2007), and work is needed that does not just identify victims as provocateurs of their own abuse, but rather uncovers factors like we have in this study—evidence that some of the blame for abuse should be put back on the abusive actor (the manager) and his/her/their own characteristics.

As well, our model supported that racial microaggressions were an employee perceptual factor linking manager implicit racial bias to abusive supervision. As mentioned earlier, implicit racial bias is difficult to fully mask. Humans are prone to “leakage” via verbal and nonverbal cues (Richeson & Shelton, 2005). Even in this era where racial discrimination has become more subtle and often takes the form of microaggressions, implicit racial bias is detectable in same-race as well as other-race observers (Cooper et al., 2012). Our study provided evidence that manager racial implicit bias may be detectable by employees in the form of racial microaggressions.

On a more hopeful note, we sought to not only document mistreatment in mixed-race manager-employee dyads, but to suggest a possible disrupter to this workplace social problem. Our model supported that, in mixed-race dyads, for managers who engaged in more individualized consideration of employees (as reported by those employees), this behavior was able to offset some of the effects of their implicit racial bias on both racial microaggressions and abusive supervision. In making this prediction we made a novel theoretical pairing of social identity and social categorization with individuation theory. Because this finding was supported, our study offers a potential boundary condition to social identity theory. That is, managers will not always fall prey to category-based social processing in their actions toward employees. Some managers may rise above default ingroup favoritism to view other-race employees as individuals rather than simply members of an outgroup. Future research may explore which managers and under what conditions this “behavior over bias” effect may occur. We return to the implications of this finding in the Practical Implications section below.

Beyond being the first study to empirically demonstrate a link between racial bias and abusive supervision, testing racial microaggressions as the linking pin between racial bias and abusive supervision, and demonstrating a behavior that possibly ameliorates these relations, as discussed above, our study makes an additional methodological contribution. Back to the time of the pioneering cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead, it has been argued that racial associations and biases run “terribly, terribly deep” (Mead & Baldwin, 1971, pp. 28–33). Hence, we felt it necessary to use a contemporary research method that would be an effective measure of managers’ deep racial biases, and that acknowledged social desirability concerns and persons’ own inability to recognize bias within themselves. So we administered IATs to our manager sample. Interestingly, implicit association tests are assumed to predict biased behavior, despite only “a handful of studies…[examining] their predictive validity…in field settings” (Oswald et al., 2013). We add our study to the merely 100 or so studies across disciplines that have attempted to link race IAT results to racial discrimination in behavior and judgments (Greenwald et al., 2015). Meta-analytic results suggest that the predictive validity of black-white race IATs on discriminatory behavior and judgments is approximately r = 0.20 (Greenwald et al., 2015), which was, remarkably, exactly the same as our study’s correlation between IAT and racial microaggressions as well as our correlation between IAT and abusive supervision.

Practical implications

Recent research has demonstrated that implicit bias does have real, salient implications for employees at work, such as an impact on interview decisions (Agerström & Rooth, 2011) and performance ratings (Anderson et al., 2015). Bias does translate into discrimination, even if the effect sizes are small to medium in society (Oswald et al., 2013). Meta-analyses (e.g., Triana et al., 2015) have provided strong evidence that racial discrimination has detrimental effects on victimized employees as far as work attitudes, coping behavior, physical and psychological health, extra-role behavior, and perceptions of organizational diversity climate (p. 491). To this large body of evidence on the negative effects of racial discrimination, our study speaks to the related question of “What happens when the discrimination is coming directly from the manager?” Employees count on managers for the provision of needed resources (e.g., via leader-member exchange and perceived organizational support; Eisenberger et al., 2014), so extreme demands/stressors originating from the manager, of which microaggressions and abusive supervision could be considered types, perhaps magnify the detrimental victim outcomes already established in the race discrimination literature.

Beyond its negative effects on the victim, race-based aggression and discrimination have negative implications for observers in organizations and overall organizational performance, for example, as organizational members may feel a sense of vicarious injustice (e.g., Truong et al., 2016). Beyond the organization, race-based discrimination has macro effects on economies: Workers who are racially discriminated against tend to have lower workforce attachment, with real implications for economic productivity, societal contributions, and group-level well-being.

Yet, perhaps the most practical implication for organizational action comes from our finding that managers who engaged in the transformational leadership behavior of individualized consideration were apparently able to overcome some of the biases predicted by social identity group processing. That is, managers in mixed-race dyads whose employees reported the manager engaged in more individualized consideration, were seen as engaging in fewer racial microaggressions and lower abusive supervision despite their level of racial implicit bias. These managers were ostensibly individuating to a greater extent—able to see their employees as individuals, and not just as, for example, a person of another race. This piecemeal processing of judgments of others is therefore one possible antidote to managers acting on their implicit racial bias. And experimental research has found that persons can be primed to individuate—that it can be taught. For example, since the 1980s, research on perspective-taking (Davis, 1983), that is, “walking a mile in another’s shoes,” has found that it can inhibit stereotypical thinking, and promote stereotype suppression and control. Simply asking undergraduate student laboratory participants exposed to a photograph of an elderly man to write an essay where they described a day in his life from this man’s perspective was shown to change the representation of “the other” to be more closely aligned with the self (Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000). That is, the nonconscious, implicit processes of stereotyping can be morphed into conscious, explicit processes characterized by individuation. Specific to our study, transformational leadership has been developed and taught since the 1990s (Bass, 1999). While the work context and the organizational culture in which each leader is embedded likely plays a role in the ease in which individualized consideration can be enacted and whether or not it is promoted and rewarded, individualized consideration can, and based on the results of our study, should be developed in managers (Avolio & Bass, 1995). More specifically, Kelloway and Barling (2000) recommend that development of individualized consideration in managers should involve coaching and counseling them to schedule time in “management by walking around” (p. 359), to talk with, thank, listen to, and personally understand individual employees. Moreover, they provide statistically significant results that document improvements in the dimensions of transformational leadership due to training and development. Based on our model, we offer the development of individualized consideration in managers as a significant, practical implication for the prevention of workplace mistreatment due to race.

Limitations and conclusion

While we believe our study makes several contributions to the abusive supervision and racial discrimination literature, it is not without its limitations. First, we had a relatively small sample size. This impeded us from examining differences in outcomes depending on discrete race combinations within dyads, for example, the outcomes experienced by a black employee supervised by a white manager, versus a white employee supervised by a black manager. These differences are quite theoretically significant given power and status differentials by race within supervisory dyads (e.g., "think manager, think white;" Gündemir et al., 2014), and historically significant, given the context of our study: South Africa, with its Apartheid past, where certain jobs such as management positions were not allowed to be held by members of any racial groups besides whites (Bergh & Hoobler, 2018). Future research may examine how discrete racial combinations in dyads affect experiences of racial microaggressions as well as perceptions of abusive supervision. While our sample size was not large, we do note that very few studies in the management literature have been able to collect field data from managers using race-based IATs. This is difficult data to collect due to organizations’ concerns about employment law violations due to racial discrimination as well as the threat of bad press. Among the handful of studies that have collected IATs from working managers, our sample size is quite similar (e.g., Leavitt et al., 2012; Penner et al., 2010).

Our second limitation, which is also methodological, is our correlating of the error terms from some abusive supervision items with microaggression in our confirmatory factor analyses. While our alternative CFA models revealed support for two different abusive supervision and microaggression factors, our CFA modifications were not ideal practice, and we acknowledge the sizable correlation between the two scales (r = 0.61; p < 0.01). We note that the abusive supervision scale is about mistreatment but does not ask respondents to attribute the cause of this mistreatment, while the racial microaggressions items are about mistreatment over a more recent time period and ask respondents to make an attribution that this mistreatment was due to their race. This possible conceptual overlap between scales is fodder for future research. For example, scholars may examine which specific mistreatment behaviors are most likely to be attributed by the victim to their racial group membership. As well, future research using both constructs in the same model may confirm, as we have argued, that abusive supervision’s construct domain reflects more of a general sense of supervisor mistreatment, whereas microaggressions are more a report of frequency of recent behavior. Perhaps the two have different nomological networks, as well as unique, real implications for employees.

A third limitation is that we as scholars do not have an independent means of validating our current understanding of IAT scores. Oswald et al. (2013) highlighted in their meta-analysis of IAT criterion studies that it is possible that the IAT simply rank orders individuals on psychological constructs that can reliably produce positive scores across different populations and contexts, without having much to do with the modal distribution of implicit biases. Furthermore, it has been shown that performance in the IAT may be influenced by an individual’s task-switching ability (Teige-Mocigemba et al., 2008), familiarity with stimuli in the IAT, and working memory capacity (Bluemke & Fiedler, 2009).

A fourth limitation is that data were collected within a period of three months only, and, as such, were treated cross-sectionally. Therefore we acknowledge that causal inferences cannot be made.

Finally, our context may be considered a limitation but also possibly a strength of the research. As a limitation, South Africa can be viewed as a particularly race-sensitive nation, where, due to our Apartheid past and historical discrimination against all groups besides whites, race is a hot-button issue in the workplace and beyond (Seekings & Nattrass, 2008). If our model were to be tested in other nations, it could be that results would be more conservative as far as race-based aggressive outcomes. But, as Lopreato and Alston (1970) argue, testing of new theoretical ideas often calls for a more extreme “test case,” as we might call the South African context, in which to isolate and idealize the phenomenon en route to building new/qualifying old theories.

In sum, our model of the when and why of implicit racial bias’s relation to workplace mistreatment was supported. When managers are higher in implicit racial bias, employees’ reports of racial microaggressions seem to explain why abusive supervision results. However, our “behavior over bias” tenets held as well—that is, there is a distinct possibility that when managers individuate in their relations with other-race employees, they may commit less employee mistreatment. This research may encourage other organizational scholars to continue field study investigations linking racial implicit bias to other outcomes, and potentially other solutions, for victimized employees, organizations, and society.

Data availability

Available

Notes

In line with the terminology used in the South African Employment Equity Act, Act 55 of 1998, the term “colored” is used in this paper as a general depiction of people of mixed European (“white”) and African (“black”) or Asian descent (Adams et al., 2012).

Copyright © 1995 by Bernard Bass & Bruce J. Avolio. All rights reserved in all media. Published by Mind Garden, Inc. www.mindgarden.com.

References

Adams, B. G., Van de Vijver, F. J. R., & De Bruin, G. P. (2012). Identity in South Africa: Examining self-descriptions across ethnic groups. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36(3), 377–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.11.008

Agerström, J., & Rooth, D. (2011). The role of automatic obesity stereotypes in real hiring discrimination. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4), 790–805. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021594

Anderson, A. J., Ahmad, A. S., King, E. B., Lindsey, A. P., Feyre, R. P., Ragone, S., & Kim, S. (2015). The effectiveness of three strategies to reduce the influence of bias in evaluations of female leaders. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 45(9), 522–539. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12317

Arbuckle, J. L. (2017). Amos 25.0 User's Guide. Chicago: IBM SPSS.

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39. https://doi.org/10.2307/258189

Avolio, B. J., & Bass, B. M. (1995). Individual consideration viewed at multiple levels of analysis: A multi-level framework for examining the diffusion of transformational leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 199–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(95)90035-7

Axt, J. R., Ebersole, C. R., & Nosek, B. A. (2014). The rules of implicit evaluation by race, religion, and age. Psychological Science, (July), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614543801

Banaji, M. R., Roediger III, H. L., Nairne, J. S., Neath, I., & Surprenant, A. (2001). Implicit attitudes can be measured. The nature of remembering: Essays in honor of Robert G. Crowder. American Psychological Association.

Bass, B. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. Free Press.

Bass, B. M. (1999). Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(1), 9–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/135943299398410

Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational leadership (2nd ed.). Retrieved from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=psyc5&NEWS=N&AN=2005-13476-000.

Bergh, C., & Hoobler, J. M. (2018). Implicit racial bias in South Africa: How far have manager-employee relations come in “the Rainbow Nation?” Africa Journal of Management, 4, 447–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322373.2018.1522173

Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within-group agreement, non-independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analysis. In K. J. Klein & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions (pp. 349–381). Jossey-Bass.

Bluemke, M., & Fiedler, K. (2009). Base rate effects on the IAT. Consciousness and Cognition, 18, 1029–1038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2009.07.010

Booysen, L. (2007). Societal power shifts and changing social identities in South Africa : Workplace implications. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 10(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v10i1.533

Brewer, M. B. (1988). A dual process model of impression formation. In T. Srull & R. Wyer (Eds.), Advances in social cognition, 1 (pp. 1–36). Erlbaum.

Brewer, M. B., Weber, J. G., & Carini, B. (1995). Person memory in intergroup contexts: Categorization versus individuation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(1), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.1.29

Brown, R. (2000). Social identity theory: Past achievements, current problems and future challenges. European Journal of Social Psychology, 30(6), 745–778. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-0992(200011/12)30:6%3c745::AID-EJSP24%3e3.0.CO;2-O

Burton, J. P., & Hoobler, J. M. (2006). Subordinate self-esteem and abusive supervision. Journal of Managerial Issues, 18(3), 340–355.

Burton, J. P., Hoobler, J. M., & Scheuer, M. L. (2012). Supervisor workplace stress and abusive supervision: The buffering effect of exercise. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27, 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-011-9255-0

BusinessTech. (2018). South Africa will be unstable without land expropriation: Ramaphosa. 21 August. https://businesstech.co.za/news/government/266367/south-africa-will-be-unstable-without-land-expropriation-ramaphosa/.

Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR) & Involve. (2018). The value of diversity. Retrieved from https://www.out-standing.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/The-Value-of-Diversity-INvolve-x-Cebr-V1.pdf.

Cooper, L. A., Roter, D. L., Carson, K. A., Beach, M. C., Sabin, J. A., Greenwald, A. G., & Inui, T. S. (2012). The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. American Journal of Public Health, 102(5), 979–987. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300558

Cunningham, W. A., Preacher, K. J., & Banaji, M. R. (2001). Implicit attitude measures: Consistency, stability, and convergent validity. Psychological Science, 12(2), 163–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00328

Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113

Dhanani, L. Y., Beus, J. M., & Joseph, D. L. (2017). Workplace discrimination: A meta-analytic extension, critique, and future research agenda. Personnel Psychology, 71, 147–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12254

Eisenberger, R., Shoss, M. K., Karagonlar, G., Gonzalez-Morales, M. G., Wickham, R. E., & Buffardi, L. C. (2014). The supervisor POS–LMX–subordinate POS chain: Moderation by reciprocation wariness and supervisor’s organizational embodiment. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(5), 635–656. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1877

Ellemers, N., Spears, R., & Doosje, B. (1999). Social identity. Blackwell.

Ellis, J. M., Powell, C. S., Demetriou, C. P., Huerta-Bapat, C., & Panter, A. T. (2019). Examining first-generation college student lived experiences with microaggressions and microaffirmations at a predominately White public research university. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(2), 266–279. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000198

Fiske, S. T, & Neuberg, S. L. (1990). A continuum of impression formation, from category-based to individuating processes: Influences of information and motivation on attention and interpretation. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology, 23, 1–74. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60317-2

Franklin, A. J. (2004). From brotherhood to manhood: How Black men rescue their relationships and dreams from the invisibility syndrome. Wiley.

Galinsky, A. D., & Moskowitz, G. B. (2000). Perspective-taking: Decreasing stereotype expression, stereotype accessibility, and in-group favoritism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(4), 708–724. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.708

Greenwald, A. G., Banaji, M. R., & Nosek, B. A. (2015). Statistically small effects of the Implicit Association Test can have societally large effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108, 553–561. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000016

Gündemir, S., Homan, A. C., de Dreu, C. K., & van Vugt, M. (2014). Think leader, think white? Capturing and weakening an implicit pro-white leadership bias. PLoS One, 9(1), e83915. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0083915

Hall, W. J., Chapman, M. V., Lee, K. M., Merino, Y. M., Thomas, T. W., Payne, B. K., … & Coyne-Beasley, T. (2015). Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 105(12), e60–e76.

Harris, K. J., Harvey, P., & Kacmar, K. M. (2011). Abusive supervisory reactions to coworker relationship conflict. Leadership Quarterly, 22, 1010–1023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.07.020

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85, 14–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100

Hershcovis, M. S., Turner, N., Barling, J., Arnold, K. A., Dupré, K. E., Inness, M., LeBlanc, M. M., & Sivanathan, N. (2007). Predicting workplace aggression: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 228–238. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.228

Hirsh, E., & Lyons, C. J. (2010). Perceiving discrimination on the job: Legal consciousness, workplace context, and the construction of race discrimination. Law & Society Review, 44(2), 269–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5893.2010.00403.x

Hoobler, J. M., & Brass, D. J. (2006). Abusive supervision and family undermining as displaced aggression. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 1125–1133. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1125

Hopkins, N., & Reicher, S. (2011). Identity, culture and contestation: Social identity as cross-cultural theory. Psychological Studies, 56(1), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-011-0068-z

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Kelloway, E. K., & Barling, J. (2000). What we have learned about developing transformational leaders. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 21(7), 355–362. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730010377908

Kim, S. S., & Vandenberghe, C. (2018). The moderating roles of perceived task interdependence and team size in transformational leadership’s relation to team identification: A dimensional analysis. Journal of Business and Psychology, 33(4), 509–527.

KZN Treasury. (2018). Province of Kwazulu-Natal Socio-Economic Review and Outlook 2017/2018. http://www.kzntreasury.gov.za/ResourceCenter/Documents%20%20Fiscal%20Resource%20Management/SERO_Final_28%20Feb%202017.pdf.

Leavitt, K., Reynolds, S. J., Barnes, C. M., Schilpzand, P., & Hannah, S. T. (2012). Different hats, different obligations: Plural occupational identities and situated moral judgments. Academy of Management Journal, 55(6), 1316–1333. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.1023

Lee, C. (2012). Making race salient: Trayvon Martin and implicit bias in a not yet post-racial society. North Carolina Law Review, 91, 102–157.

Lopreato, J., & Alston, L. (1970). Ideal types and the idealization strategy. American Sociological Review, 35, 88–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/2093855

Mackey, J. D., Frieder, R. E., Brees, J. R., & Martinko, M. J. (2017). Abusive supervision: A meta-analysis and empirical review. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1940–1965. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315573997

Martinko, M. J., Harvey, P., Brees, J. R., & Mackey, J. (2013). A review of abusive supervision research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(S1), S120–S137.

Mawritz, M. B., Mayer, D. M., Hoobler, J. M., Wayne, S. J., & Marinova, S. V. (2012). A trickle-down model of abusive supervision. Personnel Psychology, 65, 325–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2012.01246.x

Mead, M., & Baldwin, J. (1971). A rap on race. J. B. Lippincott.

Monteith, M. J., Voils, C. I., & Ashburn-Nardo, L. (2001). Taking a look underground: Detecting, interpreting, and reacting to implicit racial biases. Social Cognition, 19(4), 395–417. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.19.4.395.20759

Motsei, N., & Nkomo, S. M. (2016). Antecedents of bullying in the South African workplace: Societal context matters. Africa Journal of Management, 2(1), 50–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322373.2015.1126500

Nadal, K. L. (2011). The Racial and Ethnic Microaggressions Scale (REMS): Construction, reliability, and validity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 470–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025193

Nkomo, S. (2011). Moving from the letter of the law to the spirit of the law: The challenges of realising the intent of employment equity and affirmative action. Transformation, 9(2), 122–135. https://doi.org/10.1353/trn.2011.0046

Nosek, B. A., Bar-Anan, Y., Sriram, N., Axt, J., & Greenwald, A. G. (2014). Understanding and using the brief implicit association test: Recommended scoring procedures. Psychological Science, 9(12), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110938

Opotow, S., & Weiss, L. (2000). Denial and the process of moral exclusion in environmental conflict. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 475–490. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00179

Oswald, F. L., Mitchell, G., Blanton, H., Jaccard, J., & Tetlock, P. E. (2013). Predicting ethnic and racial discrimination: A meta-analysis of IAT criterion studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(2), 171–192. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032734

Penner, L. A., Dovidio, J. F., West, T. V., Gaertner, S. L., Albrecht, T. L., Dailey, R. K., & Markova, T. (2010). Aversive racism and medical interactions with Black patients: A field study. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(2), 436–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.11.004

Rafferty, A. E., & Griffin, M. A. (2006). Refining individualized consideration: Distinguishing developmental leadership and supportive leadership. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 79(1), 37–61. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905X36731

Richeson, J. A., & Nussbaum, R. J. (2004). The impact of multiculturalism versus color-blindness on racial bias. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 417–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2003.09.002

Richeson, J. A., & Shelton, J. N. (2005). Brief report: Thin slices of racial bias. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 29(1), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-004-0890-2

Rudman, L. A. (2011). Implicit measures for social and personality psychology. Sage Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473914797

Seekings, J., & Nattrass, N. (2008). Class, race, and inequality in South Africa. Yale University Press.

South African Human Rights Commission. (2018). Research brief on race and equality in South Africa 2013–2017. https://www.sahrc.org.za/home/21/files/RESEARCH%20BRIEF%20ON%20RACE%20AND%20EQUALITY%20IN%20SOUTH%20AFRICA%202013%20TO%202017.pdf.

Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(3), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/2695870

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271

Tajfel, H. (1981). Social stereotypes and social groups. In J. Turner & H. Giles (Eds.), Intergroup behaviour (pp. 144–167). Blackwell.

Teige-Mocigemba, S., Klauer, K. C., & Rothermund, K. (2008). Minimiz- ing method-specific variance in the IAT: A single block IAT. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 24, 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.24.4.237

Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 178–190. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556375

Tepper, B. J. (2007). Abusive supervision in work organizations: Review, synthesis, and research agenda. Journal of Management, 33(3), 261–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307300812

Tepper, B. J., Duffy, M. K., Henle, C. A., & Lambert, L. S. (2006). Procedural injustice, victim precipitation, and abusive supervision. Personnel Psychology, 59, 101–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00725.x

Tepper, B. J., Moss, S. E., & Duffy, M. K. (2011). Predictors of abusive supervision: Supervisor perceptions of deep-level dissimilarity, relationship conflict, and subordinate performance. Academy of Management Journal, 54(2), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2011.60263085

Tepper, B. J., Moss, S. E., Lockhart, D. E., & Carr, J. C. (2007). Abusive supervision, upward maintenance communication, and subordinates’ psychological distress. Academy of Management Journal, 50(5), 1169–1180. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159918

Triana, M. D. C., Jayasinghe, M., & Pieper, J. R. (2015). Perceived workplace racial discrimination and its correlates: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(4), 491–513. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1988

Truong, K. A., Museus, S. D., & McGuire, K. M. (2016). Vicarious racism: A qualitative analysis of experiences with secondhand racism in graduate education. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 29(2), 224–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2015.1023234

Turner, J. C., Oakes, P. J., Haslam, S. A., & McGarty, C. (1994). Self and collective: Cognition and social context. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(5), 454–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167294205002

Wight, A. (2018). Can we be bothered? How racism persists in the workplace. Personnel Today. 23 March. https://www.personneltoday.com/hr/modern-racism-binna-kandola-book-danger-of-indifference/.

Zhang, Y., & Bednall, T. C. (2016). Antecedents of abusive supervision: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Business Ethics, 139(3), 455–471.

Ziegert, J. C., & Hanges, P. J. (2005). Employment discrimination: The role of implicit attitudes, motivation, and a climate for racial bias. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(3), 553–562. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.3.553

Funding

This study was supported in part by the National Research Foundation of South Africa, Grant Number 110835.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study was done as partial fulfilment of the first author's Ph.D. in Industrial and Organizational Psychology at the University of Pretoria, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of the research.

Conflict of interest/Competing interests

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bergh, C., Hoobler, J.M. Why and when is implicit racial bias linked to abusive supervision? The impact of manager racial microaggressions and individualized consideration. Curr Psychol 42, 22036–22049 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03292-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03292-8