Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between perfectionism, rumination, and depression severity in non-clinical and clinical populations. To this end, a sample of 151 Argentinian university students (i.e., the non-clinical sample) and a sample of 42 Argentinian outpatients in psychotherapy with a diagnosis of a depression (i.e., the clinical sample) completed the Almost Perfect Scale, Beck’s Depression Inventory, the Rumination–Reflection Questionnaire and the Positive Beliefs About Rumination Scale. We found an association between maladaptive perfectionism, rumination, and depressive symptomatology, in both samples. Also, the study yielded differences between the profiles of perfectionism for the variables rumination and depressive symptomatology. Rumination mediated the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and depression. Finally, we found that the level of endorsement of positive beliefs about rumination moderated the indirect effect of maladaptive perfectionism on depression. The implications of these results for clinical intervention are discussed, both in relation to the different profiles of perfectionism and to rumination as a cognitive mechanism of emotion regulation. Among the limitations of this study we can mention the use of self-report measures and the fact that the non-clinical sample was entirely obtained from a population of mostly female students of Psychology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Perfectionism is a personality disposition (Stoeber, 2018) that has been linked to the etiology and maintenance of diverse psychopathologies, such as eating disorders (Bardone-Cone et al., 2007; Kehayes et al., 2019; Shafran & Mansell, 2001), mood disorders (Dunkley et al., 2006; Hewitt et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2018a, 2020), anxiety disorders (Bieling et al., 2004; Kawamura et al., 2001; Moretz & Mc Kay, 2009; Smith et al., 2018b), and suicide (Smith et al., 2018c). Hence, some researchers have suggested that perfectionism is a transdiagnostic process (Egan et al., 2011).

Frost et al. (1990) have defined perfectionism as the tendency to set oneself high standards for performance, together with an excessively critical self-evaluation, and a growing concern about making mistakes. Currently, there is strong consensus in conceptualizing perfectionism as a multidimensional construct (Stoeber, 2018). Although different research teams have coined different terms to name these dimensions, most of these can be summarized as perfectionist strivings and perfectionist concerns (Stoeber, 2018; Stoeber & Otto, 2006). Perfectionist strivings refer to setting high standards for oneself, as well as the tendency to search for perfection. This dimension often shows positive correlation with characteristics, processes and outcomes that are considered desirable or adaptive (such as active coping or positive affect).

Instead, perfectionist concerns refer to the fear of making mistakes, doubts about actions, fear of being negatively evaluated by others, and discrepancy between expectations and self-performance. This dimension often correlates positively with maladaptive aspects and outcomes (neuroticism, avoidance, negative affect) (Stoeber, 2018).

The different models of perfectionism have generated different tools for its assessment. Slaney and his team (Slaney et al., 1996) created the Almost Perfect Scale-Revised (APS-R). The APS-R has three subscales: high standards (a preference for high standards for self-performance), order (a preference for order) and discrepancy (the perceived distance between standards and actual achievement). The subscales allow us to identify the profiles of perfectionism. Thus, adaptive perfectionists (AP) present high standards for performance but low discrepancy, whereas maladaptive perfectionists (MP) evidence both high standards for performance and high discrepancy. Rice and Slaney (2002) hold that perfectionists do not suffer due to their high standards or actual performance, but due to the distance perceived between them, i.e., the discrepancy. In their view, discrepancy is the maladaptive or negative aspect of perfectionism (Slaney et al., 2001). Of course, many people do not set high standards for their own performance. Hence, they score as non-perfectionists (NP).

There is growing interest in studying the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and depression. Our study focuses on rumination, an intrapersonal cognitive process. However, other authors (Smith et al., 2018a) have focused on interpersonal processes that mediate the relationship between perfectionism and depression. Future research may shed light on how these two levels of analysis are related.

Rumination, Perfectionism, and Metacognition

Rumination is a transdiagnostic, cognitive mechanism of emotion regulation, present in depression, anxiety, eating disorders, alcohol abuse, pain disorders and other conditions, such as hypertension (Connolly et al., 2007; Fritz, 1999; Garnefski et al., 2002; Gerin et al., 2012; Gracie et al., 2006; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema & Harrell, 2002; Tremblay et al., 2008).

Lately, there has been a growing interest in investigating mechanisms of emotion regulation such as rumination, since they are considered to be a key factor for cognitive vulnerability to several mental disorders, particularly depression (De Rosa & Keegan, 2018a, b). In her famous attempt to account for the prevalence of depression in women, Nolen-Hoeksema (1987) proposed her theory of response styles. According to this theory, rumination involves a repetitive, passive focus on thoughts about situations with a negatively-valenced content that contributes to the maintenance of depressive disorders (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1994). These thoughts typically 1) refer to the antecedents of negative mood, 2) are of passive nature, since they are not oriented to a target or plan to correct that which leads to the negative mood, and 3) are associated with social withdrawal. Individuals with a ruminative response style focus repetitively on the causes, meaning and consequences of depressive symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991), thus increasing their distress.

The relationship between perfectionism and rumination as a diathesis of depression has been subject to research. Olson and Kwon (2008) found that perfectionism does not only function as a diathesis, but also that this vulnerability is activated and potentiated by rumination. This association is so significant that these authors propose a subtype of perfectionism: ruminative perfectionism. Thus, this subtype would be a key factor in the increase of depressive symptoms. Along these lines, some authors (Harris et al., 2008) found that rumination is a mediator between maladaptive perfectionism and depressed mood. These authors suggest that rumination is part of a cognitive process that might emerge from maladaptive perfectionism and lead to depressive symptoms.

Rumination is also related to metacognition, as proposed by Wells and Matthews (1994) in their model of self-regulatory executive function (S-REF). These authors study the relationship between attention, the regulation of cognition, beliefs about emotion regulation strategies and the interactions between the different levels of cognitive processing. According to this model, metacognitive beliefs play a role in the development of rumination as a stable response style. Metacognition refers both to the beliefs about what we think and to the ability to monitor and regulate cognitions (Wells & Matthews, 1994, 1996). Positive beliefs about rumination would play an important role in the maintenance of this cognitive mechanism. Watkins and Baracaia (2001) highlight that ruminators believe rumination to be advantageous because it leads to increased self-awareness. Papageorgiou and Wells (2001a) found that ruminators believed rumination was an adaptive strategy. In a series of studies, Papageorgiou and Wells (2001b) found that positive beliefs about rumination included thinking that rumination improved problem-solving by means of increasing introspection, thus helping with identifying the causes and triggering factors of depression and with avoiding future mistakes and failure. Thus, beliefs such as “I need to ruminate about my problem in order to find answers to my depression” or “ruminating about the past will help me prevent future mistakes” maintain maladaptive ruminative activity. Also, a significant relationship between positive beliefs about rumination and depression was established (Papageorgiou & Wells, 2001b; Watkins & Moulds, 2005). Roelofs et al. (2007) found that positive beliefs about rumination mediated the relationship between self-discrepancy (Higgins, 1987) and rumination in a group of Dutch students. Thus, the evidence suggests that rumination is linked to multiple cognitive processes in a complex framework.

Aims and Hypotheses of the Study

This study aims at investigating the relationship between profiles of perfectionism, rumination and depression severity, in both clinical and non-clinical populations. More specifically, we put four hypotheses to the test:

-

1-

There is an association between maladaptive perfectionism, rumination and depressive symptomatology, both in the clinical and non-clinical samples.

-

2-

There are differences in rumination and depression severity between profiles of perfectionism (i.e., AP, MP, and NP) after controlling for sampling effect.

-

3-

Rumination mediates the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and depression.

-

4-

The degree of endorsement of positive beliefs about rumination moderates the indirect effect of maladaptive perfectionism on depression by rumination.

Methods

Participants

One hundred ninety-three individuals, divided into two samples, participated in the study. Cases were chosen through a non-probabilistic convenience sampling (Miles & Banyard, 2007).

Non-clinical sample: it was integrated by 151 undergraduate students from the University of Buenos Aires. Students were contacted through their lecturers, who informed them about the study and offered contact details to those interested in participating. In this sample, participants with a diagnosis of mental and behavioral disorder were excluded. The participants of the study had a mean age of 26.25 years (SD = 6.03). They were mostly female (86.1%), Argentinian (99.3%), and were single (86.1%), and without children (89.4%) at the moment the study was conducted. Regarding job distribution, 49.7% of the participants were employed part-time, 18.5% were employed full-time, 11.3% worked occasionally and 20.5% of them did not work.

Clinical sample: 42 treatment-seeking outpatients admitted into a cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy in Buenos Aires, Argentina. The therapists, all trained and supervised in cognitive-behavioral therapy, and with over 5 years of clinical practice, assessed clients and identified the presence of a mood disorder according to DSM-5 criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). 40.5% of participants in the clinical sample had a diagnosis of single episode major depressive disorder, 28.6% of them were diagnosed with recurrent episode major depressive disorder, 16.7% with persistent depressive disorder, 9.5% with single episode major depressive disorder comorbid with persistent depressive disorder and 4.7% with another mood disorder. In this second sample, had a mood disorder as the only primary diagnosis, comorbidities were excluded. Clients with a diagnosis of bipolar depression, mood disorder due to medical condition or induced by substances and other mental disorders were excluded from the study. The initial contact with the clients of this sample was established through their therapists. Participation in the study was voluntary.

The participants of this sample had a mean age of 36.76 years (SD = 9.56). They were female (57.1%), male (42.9%), Argentinian (100%), and were single (50%), married or cohabiting (40.5%), divorced (9.5%), and without children (59.5%) at the moment the study was conducted. Regarding job distribution, 50% of the participants 50% were employed full-time, 26.2% were employed part-time, 9.5% worked occasionally and 14.3% of them did not work.

Measures

Almost Perfect Scale-Revised-APS-R- (Slaney et al., 2001)

This scale evaluates different dimensions of perfectionism. It consists of 23 items with a Likert scale of 7 options, according to the degree of endorsement of each statement (from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”). The tool consists of three subscales: high standards, order and discrepancy. The first subscale (7 items) assesses the presence of high standards for performance. The second subscale (4 items) measures the preference for order and tidiness. The last subscale (12 items) evaluates the degree to which the examined person perceives herself as incapable of reaching her own standards for performance. Profiles of perfectionism emerge from the combination of the scores of the subscales. Thus, adaptive perfectionism results from the combination of high scores in high standards and low scores in discrepancy. Maladaptive perfectionism is the result of high scores in high standards and in discrepancy. Finally, non-perfectionists score low on the high standards subscale.

Regarding psychometrics, confirmatory and exploratory factorial analyses supported the internal structure of the scale, representing a three-factor solution. Internal consistency reached satisfactory levels (Slaney et al., 2001). Test-retest reliability oscillated between scores of .72 and .87 in three- to ten-week intervals (Grzegorek et al., 2004).

Arana et al. (2009) explored the psychometric properties of the Almost Perfect Scale-Revised (APS-R) in a sample of Argentinian university students (n = 268) of the Universidad de Buenos Aires. The adaptation showed solid psychometric properties. For the sake of brevity, we refer the reader to this paper.

Beck’s Depression Inventory, 2nd. Edition (BDI II; Beck et al., 1996)

Both the original instrument and the local adaptation (Brenlla & Rodríguez, 2006) consist of 21 items that assess the severity of the cognitive, emotional, motivational and physiological symptoms of depression in adults and teenagers. Five to six years of schooling are required to understand the statements. Every item presents 4 possible responses, representing the increasing severity of different symptoms of depression. The inventory has good sensitivity (94%) and moderate specificity (92%) for the screening of depression in primary care, with a cut-off score for depression of 18 points. The Argentinian adaptation showed good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88 for depressed clients and of 0.86 for participants in the control group. In the sample of the current study the BDI showed very good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91).

Rumination–Reflection Questionnaire (RRQ; Trapnell & Campbell, 1999, Adapted by De Rosa & Keegan, 2018b)

The questionnaire consists of 24 items, 12 assessing reflection and 12 evaluating rumination, with Likert-type response options (1-“strong disagreement” to 5- “strong agreement”). Trapnell and Campbell (1999) define rumination as a process of recurrent thinking involving self-focused attention on thoughts related to threat, loss or injustice associated to anxiety, depression and anger, respectively. They define reflection as a thinking process motivated by an epistemic curiosity about the self. Reflection is an abstract, pleasant activity of a philosophical kind, and is not associated to distress. Trapnell and Campbell (1999) reported good internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91 for the factor reflection and 0.90 for the factor rumination. In the sample of the current study the RRQ factor rumination showed a good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79).

Positive Beliefs about Rumination Scale (PBRS; Papageorgiou & Wells, 2001a, 2001b)

This Likert-type scale of 4 response options consists of 9 items assessing positive metacognitive beliefs about rumination. This scale evaluates metacognitive beliefs about rumination (for example, “I need to ruminate about my problems to find answers to my depression”).

The PBRS has good test-retest reliability (r = 0.85), high internal consistency (α = 0.89) and convergent and discriminant validity (Papageorgiou & Wells, 2001a, 2001b). In the sample of the current study the PBRS showed very good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87).

Procedure

All the instruments were administered to individuals who volunteered to participate in the study once they had given their informed consent. Participants were informed about the nature of the study and the confidentiality of the information provided was guaranteed.

Participants from both samples were informed about the nature of the research project. They received an informed consent form detailing all the information about the study, guaranteeing confidentiality and the right of participants to abandon the study at any time. Only those who voluntarily accepted to participate and gave their informed consent were given the self-administered instruments for completion. All instruments were completed by the participants at the same time. Participants of the clinical sample were undergoing psychotherapeutic treatment and were in the initial phase of the same (session 1 to 3).

Profiles of perfectionism were established according to the cut-off scores of the subscales of the local adaptation of the APS-R (Arana et al., 2009). Thus, all participants from both samples were classified according to profiles of perfectionism as non-perfectionist (NP), adaptive perfectionist (AP), and maladaptive perfectionist (MP).

Data Analyses

To test the hypothesis of association between the targeted variables of the study (Hypothesis 1), we ran separate Pearson’s correlations among them for the clinical and non-clinical sample. We applied a Bonferroni correction to adjust the level of significance to the correlations proposed. We used a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) to test if the profiles of perfectionism were related to differential levels of depression and rumination (Hypothesis 2), due to the multiple dependent variables. In this analysis, we simultaneously included as outcome variables the severity of depression, the total level of rumination, the levels of rumination brooding, those of rumination reflection, and the positive beliefs about ruminating. As between-participant factors we included the profiles of perfectionism (AP, MP, NP) and the sample of the participants (clinical vs. non-clinical sample). When significant effects were found, we ran posthoc multiple comparison tests with Bonferroni procedures to analyze between which profiles there were significant effects. Both the correlations of hypothesis 1 and MANOVAs of hypothesis 2 were conducted in SPSS 23.

In order to analyze the mediation effects of rumination on the association between perfectionism and depression severity (Hypothesis 3), we used ordinary least squares regression methods with the PROCESS macro version 2.11 (Hayes, 2013) for SPSS. This plug-in applies asymptotic bootstrapping computations providing optimized significance tests for mediation and moderation effects (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). For these analyses we used bias corrected standard errors and calculated confidence intervals based on 5000 bootstrapped samples. Although these methods do not provide a p value for the indirect effects, the results are considered significant when the zero is not included within the limits bias corrected bootstrap confidence intervals estimated for this indirect effect. For hypothesis 3 we used a simple mediation model (Model 4 in PROCESS procedures; Hayes, 2013) in which the independent variable was having a MP profile (i.e., dichotomized variable, MP = 1, non-MP = 0), the dependent variable was BDI total scores, and the mediator was the total score in the rumination scale. In this model we included the sample of participants (clinical versus non-clinical) as a covariate to control for its effect.

Finally, in order to test the Hypothesis 4 of the study, we calculated moderated mediation with the PROCESS macro tool, using ordinary least squares regressions and bootstrapping procedures. In this model (Model 14 in the PROCESS; Hayes, 2013), we included positive beliefs about rumination as the B path of the indirect effect analysed for Hypothesis 3 (i.e., the association between rumination and depression severity). Based on this model, we calculated an index of moderated mediation to test if participants’ positive beliefs moderate the indirect effect of MP on depression severity by rumination.

Results

Sample Descriptives

Table 1 reflects the descriptive results of the different variables under study, both for the full sample and separately for the clinical and non-clinical samples. Student’s t test showed statistically significant differences between the samples in RRQ Total, RRQ Brooding, PBRS and BDI-II. As expected, the clinical sample mean scores were higher in all cases. Moreover, the study yielded significant differences in APS-R Standards, with higher mean scores in the non-clinical sample and also in APS-R Discrepancy, with higher mean scores in the clinical sample.

Additionally we did not find differences in any measure of rumination, and depression for gender in the total sample [Depression (BDI): t(191) = 1.43, p = .15; Rumination (RRQ): t(151) = 1.90, p = .06; Rumination Brooding (RRS Brooding): t(191) = −.35, p = .72; and Rumination Brooding (RRS Brooding): t(191) = −.29, p = .77].

Relationship between Measures of Perfectionism, Depressive Symptomatology and Rumination in Clinical and Non-Clinical Population (Hypothesis 1)

Table 2 presents the correlations between the scores of the subscales of perfectionism, rumination, positive beliefs about rumination and BDI-II, differentiated for the clinical and non-clinical samples. The clinical sample evidenced a statistically significant, positive, moderate association between maladaptive perfectionism and ruminative processes, specifically between rumination (RRQ) and the Discrepancy subscale (APS-R), r = .536, p < .001. Also, a statistically significant association between Rumination Brooding and Discrepancy (APS-R), r = .541, p < .001 was found. Furthermore, the study revealed a statistically significant, positive association between Discrepancy (APS-R) and Depression, as measured by BDI-II scores, r = .648, p < .001. No statistically significant relationship between ruminative processes and high standards was found in the clinical sample.

The study also revealed a positive, statistically significant association between perfectionism and ruminative processes in the non-clinical sample. Specifically, we found a positive association between High Standards (APS-R) and Rumination Brooding (RRS Brooding), r = .288, p < .001. Also, positive associations were found between subscale Discrepancy (APS-R) and Rumination (RRQ), r = .410, p < .001, and Rumination Brooding (RRS Brooding), r = .356, p < .001. The association between Discrepancy (APS-R) and scores in symptoms of depression (BDI-II) was also positive, r = .507, p < .001.

Differences in Levels of Depression and Rumination According to Profiles of Perfectionism (Hypothesis 2)

The MANOVAs showed multivariate effects on all dependent variables according to the profiles, [F(10,366) = 2.63, p < .01], the kind of sample (clinical versus non-clinical), [F(5,183) = 28.11, p < .001], and their interaction, [F(10,366) = 28.11, p = .04]. Univariate tests showed significant differences, according to profiles, in the dependent variables Positive beliefs about rumination, [F(2,187) = 5.41, p < .01], RRQ Rumination, [F(2,187) = 5.12, p < .01], Rumination Brooding, [F(2,187) = 3.10, p < .05], and BDI-II, [F(2,187) = 7.14, p < .01]. However, we did not observe a statistically significant difference in Rumination Reflection in terms of the profile of the participants, [F (2,187) = 2.81, p = .06].

Univariate tests did show significant differences, depending on type of sample, for the dependent variables RRQ Rumination, [F(1,187) = 31.63, p < .001], and BDI-II, [F(1,187) = 16.37, p < .001]. Instead, no statistically significant differences were found, according to type of sample, for the variables Positive beliefs about rumination, [F(1,187) = 1.62, p < .21], Rumination Brooding, [F(1,187) = 3.82, p = .05], and Rumination Reflection, [F(1,187) = .25, p = .62].

Finally, univariate analyses did not yield significant differences, taking into account type of sample and interaction of profiles, in none of the dependent variables: Positive beliefs about rumination, [F(2,187) = .86, p = .43], RRQ Rumination, [F (2,187) = .48, p = .62], Rumination Brooding, [F(2,187) = 2.49, p = .09], Rumination Reflection,[F(2,187) = 1.90, p = .15], and BDI-II, [F(2,187) = 2.37, p = .10].

Posthoc analyses showed that maladaptive perfectionists obtained significantly higher mean scores that non-perfectionists in (i) Positive beliefs about rumination, mean difference[MD] = 2.99, standard error [SE] = 1.42, p < .01, (ii) RRQ Rumination, MD = 3.39, SE = 1.16, p = .01, (iii) Rumination Brooding, MD = 2.80, SE = 0.73, p < .001, and (iv) Rumination Reflection, MD = 1.57, SE = 0.64, p < .05. Additionally, maladaptive perfectionists obtained significantly higher means than adaptive perfectionists in RRQ Rumination, MD = 6.26, SE = 1.71, p < .01, y BDI, MD = 7.11, SE = 1.90, p < .01. No significant differences were found between profiles of adaptive perfectionism and non-perfectionists.

Rumination as a Mediator of the Associations between Maladaptive Perfectionism and Depressive Symptomatology (Hypothesis 3)

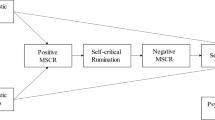

The results of the mediation models showed that having maladaptive perfectionism was significantly related to the levels of rumination of participants, B = 3.84, SE = 1.12, CI95 [1.62, 6.07], t = 3.40, p < .001. Having maladaptive perfectionism was associated with an increase of 3.84 units in the scores in rumination. Besides, the level of rumination of participants predicted were significantly related with depression severity in BDI-II, B = .42, SE = 0.08, CI95 [.27, .57], t = 5.57, p < .001. Each one-unit increase in the scores of rumination was linked to 0.42 units increase in the BDI-II score. Finally, mediational analyses showed a significant indirect effect of maladaptive perfectionism on the BDI-II scores by rumination, B = 1.63, SE = 0.54, CI95 [.75, 2.92] (See Fig. 1).Footnote 1 Finally, when controlling for the effect of mediation, the direct effect of the MP profile on the BDI-II scores was not statistically significant, B = 2.03, SE = 1.22, CI95 [−.37, 4.44], t = 1.67, p = .09.

Positive Beliefs as a Moderator for the Mediating Effect of Rumination (Hypothesis 4)

As in the mediation model, in the model of moderated mediation the fact that participants had MP was significantly associated with higher levels of rumination, B = 3.84, SE = 1.12, CI95 [1.62, 6.07], t = 3.40, p < .001. In addition to the results of the mediation model, this model showed that the level of endorsement of beliefs about rumination moderated the effect of rumination on the BDI-II scores, B = 0.03, SE = .01, CI95 [0.004, 0.05], t = 2.35, p = .02. In participants with high endorsement of positive beliefs about rumination (i.e., with a score a standard deviation over the mean, that is, 22.78) the effect of rumination on the BDI-II scores was bigger (i.e. 2.29) than in clients with lower levels of positive beliefs (i.e., with a score one standard deviation under the mean, that is, a score of 11.27), for whom the effects were more moderate (i.e. 1.17). Finally, the analyses yielded a significant index of moderated mediation = .10, SE = .06, CI95 [0.01, 0.25], suggesting that the indirect effect of the MP profile on the levels of the scores of the BDI-II by rumination was moderated by the positive beliefs about rumination (Hayes, 2015). When controlling for the moderated mediation effect, the direct effect of maladaptive perfectionism on the BDI-II scores was not significant, B = 1.55, SE = 1.22, CI95 [−.87, 3.96], t = 1.26, p = .21 (See Fig. 2).

Discussion

Results show that the maladaptive aspect of perfectionism is associated with rumination, in both the clinical and non-clinical populations. This means that the higher the level of discrepancy, the higher the presence of rumination. Also, these two variables were associated with the presence of depressive symptomatology. Our first hypothesis was confirmed both in the clinical and in the non-clinical samples, as we found associations between these variables in the expected direction. These results match the evidence obtained in other studies (Flett et al., 2002; Harris et al., 2008; Olson & Kwon, 2008). They also match the results yielded by previous local studies with university students of the city of Buenos Aires (De Rosa & Keegan, 2018a, 2018b).

The second hypothesis that guided this study stated that differences between the profiles of perfectionism (i.e., AP, MP, and NP) for the variables rumination and depression would be found. This hypothesis was also corroborated, even after controlling for the effect of the participants´ sample. Participants with a MP profile obtained significantly higher scores in rumination (RRQ) and in positive beliefs about rumination than the rest of participants, whereas participants with AP and NP profiles showed no differences for these variables. Therefore, we may posit that the factor of discrepancy, highly present in maladaptive perfectionism, would activate self-criticism, and, in an attempt to regulate the perceived distress, this would increase ruminative activity. Contrarily, adaptive perfectionists and non-perfectionists score low in discrepancy and show low levels of self-criticism and rumination. This is congruent with the findings of Slaney et al. (2001), who asserted that maladaptive perfectionists do not suffer due to their high standards or their actual performance, but due to the perceived gap between them, i.e., the discrepancy. These findings also match the results of a previous study conducted in Argentina (De Rosa & Keegan, 2018a, 2018b).

The third hypothesis of this study, that which postulates that rumination would mediate the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and depressive symptomatology, was also supported. Participants with maladaptive perfectionism tended to ruminate more, and this was, in turn, associated with greater depression severity. It is worth noting that when controlling for this mediational effect, the main effect of maladaptive perfectionism on depression severity was not significant. Perfectionism is characterized by the tendency to set oneself high standards, and by a dysphoric mood due to the perception of personal failure (Flett et al., 1998). Perfectionist individuals may ruminate about their perceived failures and their need to be perfect, thus focusing on the discrepancy between what they are not and the ideal that they have set for themselves (Flett et al., 2002). The action of rumination on the discrepant valuations of the self amplifies discrepancy and negative mood. Along these lines, Harris et al. (2008) showed that rumination mediates between maladaptive perfectionism and depressed mood response. These authors suggest that ruminations are a part of a cognitive process that might originate from maladaptive perfectionism and lead to depressive symptoms. These results provided evidence in favour of this theoretical position.

Furthermore, Olson and Kwon (2008), as mentioned above, also studied the relationship between perfectionism and rumination as a diathesis for depression. Results support the idea that perfectionism does not only function as a diathesis, but also that this diathesis is activated and potentiated by rumination. This subtype of perfectionism –ruminative perfectionism- would be a key factor in the increase of depressive symptoms. These authors specially emphasize this relationship, naming it the “malicious combination” (p. 799), since it increases the depressive response. The results of this study further support this theory.

Finally, we found support for our last hypothesis, that which predicted that the level of endorsement of positive beliefs would moderate the indirect effect of maladaptive perfectionism on depression by rumination. The profiles of perfectionism differed in the variables rumination and positive beliefs about rumination in both samples. More precisely, and as expected, in participants with maladaptive perfectionism higher levels of rumination had a greater association with depression severity in the context of higher positive beliefs about this cognitive strategy. The indirect effect of perfectionism on depression severity by rumination implies the degree to which the relationship of perfectionism and depression severity is explained (i.e., mediated) by levels of rumination. The significant interaction of the B path by positive beliefs means that positive beliefs moderate the effects of rumination on depression severity. The greater the endorsement of positive beliefs, the stronger the association of rumination with depression severity. The non-significant direct effect in this case means that, when controlling for the indirect effect of perfectionism on depression severity by rumination, perfectionism was not related to depression severity. This finding further supports the idea that the association between perfectionism and depression is explained by the mediating effect of rumination (i.e., when controlling for that effect, the association is no longer significant).

As mentioned above, several researchers (Papageorgiou & Wells, 2001a, 2001b; Roelofs et al., 2007; Watkins & Baracaia, 2001; Watkins & Moulds, 2005) have highlighted that ruminators perceive rumination as an adaptive strategy leading to increased self-understanding and self-knowledge that would in turn facilitate problem-solving and allow the person to learn from past mistakes and prevent future ones. So, these beliefs would function as maintaining factors for rumination, thus impacting depressive symptomatology.

Limitations and Further Directions

Our study has several limitations. The first of them is that the size of the clinical sample was small and may have led to an underestimation of the effects. On the other hand, the non-clinical sample was entirely obtained from a population of students of Psychology. It would be relevant to replicate this study with different non-clinical samples, since students of Psychology might have a tendency to value rumination-reflection due to the nature of their academic interests. Also, they were mostly female. These two factors may have had some incidence on the observed phenomena, even though we did not find significant differences according to gender for the variables under study.Self-report measures also present inherent limitations, demanding the inclusion of other measures to counter potential biases in the perception of participants, mainly those related to the high expectations of perfectionist subjects and social desirability. Also, the measures used in the study have other inherent limitations (Stoeber, 2018). The lack of longitudinal studies has been highlighted as another problem in the field (Stoeber, 2018). Particularly, in this study, the cross-sectional nature of the design used did not allow us to establish temporal precedence between the targeted variables or to make causal inferences. Further longitudinal research in the area is needed that may account for the development of perfectionism and its impact in different domains of life. These studies may deepen our understanding of perfectionism, leading to increasingly effective interventions and to the prevention of problems associated with this personality disposition.

There are other potential explanations and possible causes for these processes. For instance, from a biological perspective, there is evidence that polymorphisms in the serotonin transporter and brain derived neurotropic factor genes are associated with sensitivity to the negative effects of stress, thus moderating the relationship between life stress and rumination (Clasen et al., 2011; Scaini et al., 2020).

Besides these limitations, our research provides more evidence about the phenomena under study. Our goal was to analyze the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and ruminative processes in depression, and our hypotheses were supported in both the clinical and non-clinical samples. Although rumination is not the only mediator between perfectionism and depression, this study has a clinical interest in rumination as a voluntary, transdiagnostic process oriented to emotion regulation. Cognitive-behavioral approaches view maladaptive (meta) cognitive processes as mediators between triggering factors and psychological distress. Hence, they are the main treatment target (Hofmann, 2014).

These results have two interesting implications. On the one hand, in our clinical practice we must favor interventions that match the profile of perfectionism, as a potential trigger for the process of rumination. On the other, we must target the beliefs about rumination and promote more functional strategies to deal with the distress associated with discrepancy that is intense for maladaptive perfectionists. As shown above, this mechanism has an impact on the severity of mood. Finally, these outcome data lead us to weigh the importance of identifying these phenomena and offering psychoeducation to the population in order to diminish its incidence on several mental disorders.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

As mentioned above in this bootstrapping procedures, a significant effect occurs when zero is not included within the confidence interval (Hayes, 2013).

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

Arana, F. G., Keegan, E. G., & Rutsztein, G. (2009). Adaptación de una medida multidimensional de perfeccionismo: La almost perfect scale-revised (APS-R). Un estudio preliminar sobre sus propiedades psicométricas en una muestra de estudiantes universitarios argentinos. [Adaptation of a multidimensional measure of perfectionism: The Almost Perfect Scale-Revised (APS-R). A preliminary study on its psychometric properties in a sample of Argentine university students]. Evaluar, 9, 35–53.

Bardone-Cone, A., Wonderlich, S., Frost, R., Bulik, C., Mitchell, J., Uppala, S., & Simonich, H. (2007). Perfectionism and eating disorders: Current status and future directions. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 384–405.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). BDI-II. Beck Depression Inventory. Second Edition. Manual. The Psychological Corporation.

Bieling, P. J., Israeli, A. L., & Antony, M. M. (2004). Is perfectionism good, bad, or both? Examining models of the perfectionism construct. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 1373–1385.

Brenlla, M. E., & Rodríguez, C. M. (2006). Adaptación argentina del Inventario de Depresión de Beck (BDI-II). BDI-II. Inventario de Depresión de Beck. Segunda Edición. [Beck's Depression Inventory. Second Edition: Argentine Adaptation Manual]. Editorial Paidós.

Clasen, P. C., Wells, T. T., Knopik, V. S., McGeary, J. E., & Beevers, C. G. (2011). 5-HTTLPR and BDNF Val66Met polymorphisms moderate effects of stress on rumination. Genes, Brain and Behavior, 10, 740–746.

Connolly, A. M., Rieger, E., & Caterson, I. (2007). Binge eating tendencies and anger coping: Investigating the confound of trait neuroticism in a non-clinical sample. European Eating Disorders Review, 15(6), 479–486.

De Rosa, L. & Keegan, E. (2018a). Rumiación: Consideraciones teórico-clínicas [Rumination: Theoretical-clinical considerations]. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, XXVII, 36-43. https://doi.org/10.24205/03276716.2017.1032.

De Rosa, L. & Keegan, E. (2018b). Perfeccionismo desadaptativo, autocrítica y su relación con los procesos de rumiación [Maladaptive perfectionism, self-criticism and its relationship with rumination processes]. [Tesis de Doctorado no publicada]. Universidad de Buenos Aires. Argentina.

Dunkley, D. M., Sanisow, C. A., Grilo, C. M., & Mclachlan, T. H. (2006). Perfectionism and depressive symptoms 3 years later: Negative social interactions, avoidant coping, and perceived social support as mediators. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 47(2), 106–115.

Egan, S. J., Wade, T. D., & Shafran, R. (2011). Perfectionism as a transdiagnostic process. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 203–212.

Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Blankstein, K., & Gray, L. (1998). Psychological distress and the frequency of perfectionistic thinking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1363–1381.

Flett, G. L., Madorsky, D., Hewitt, P. L., & Heisel, M. J. (2002). Perfectionism cognitions, rumination, and psychological distress. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 20, 33–47.

Fritz, H. L. (1999). Rumination and adjustment to a first coronary event. Psychosomatic Medicine, 61, 105.

Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14, 449–468.

Garnefski, N., Legerstee, J., Kraaij, V. V., Van Den Kommer, T., & Teerds, J. (2002). Cognitive coping strategies and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A comparison between adolescents and adults. Journal of Adolescence, 25(6), 603–611.

Gerin, W., Zawadski, M. J., & Brosschot, J. F. (2012). Rumination as a mediator of chronic stress effects of hypertension: A causal model. International Journal of Hypertension, 2012, 453–465.

Gracie, J., Newton, J. L., Norton, M., Baker, C., & Freeston, M. (2006). The role of psychological factors in response to treatment in neurocardiogenic (vasovagal) syncope. Europace, 8(8), 636–643.

Grzegorek, J. L., Slaney, R. B., Franze, S., & Rice, K. R. (2004). Self-criticism, dependency, self-esteem, and grade-point average satisfaction among clusters of perfectionists and non-perfectionists. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51, 192–200.

Harris, P., Pepper, C., & Maack, D. (2008). The relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and depressive symptoms: The mediating role of rumination. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 150–160.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683.

Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., Sherry, S. B., & Caelian, C. (2006). Trait perfectionism dimensions and suicidal behavior. In T. E. Ellis (Ed.), Cognition and suicide: Theory, research, and therapy (pp. 215–235). American Psychological Association.

Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy. A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94, 319–340.

Hofmann, S. (2014). Toward a cognitive behabioral classification system for mental disorders. Behavior Therapy, 45(4), 576–587.

Kawamura, K. Y., Hunt, S. L., Frost, R. O., & DiBartolo, P. M. (2001). Perfectionism, anxiety, and depression: Are the relationships independent? Cognitive Therapy and Research, 25(3), 291–301.

Kehayes, I. L. L., Smith, M. M., Sherry, S. B., Vidovic, V., & Saklofske, D. H. (2019). Are perfectionism dimensions risk factors for bulimic symptoms? A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Personality and Individual Differences, 138, 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.09.022.

Miles, J., & Banyard, P. (2007). Understanding and using statistics in psychology. SAGE Publications, Inc..

Moretz, M., & Mc Kay, D. (2009). The role of perfectionism in obsessive–compulsive symptoms: “Not just right” experiences and checking compulsions. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23, 640–644.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1987). Sex differences in unipolar depression: Evidence and theory. Psychological Bulletin, 101(2), 259–282.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 569–582.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 504–511.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Harrell, Z. A. (2002). Rumination, depression, and alcohol use: Tests of gender differences. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 16(4), 391–403.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Parker, L. E., & Larson, J. (1994). Ruminative coping with depressed mood following loss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(1), 92–104.

Olson, M., & Kwon, P. (2008). Brooding perfectionism: Refining the roles of rumination and perfectionism in the etiology of depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32, 788–802.

Papageorgiou, C., & Wells, A. (2001a). Metacognitive beliefs about rumination in recurrent major depression. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 8(2), 160–164.

Papageorgiou, C., & Wells, A. (2001b). Positive beliefs about depressive rumination: Development and preliminary validation of a self-report scale. Behavior Therapy, 32, 13–26.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879.

Rice, K., & Slaney, R. (2002). Clusters of perfectionistics: Two studies of emotional adjustment and academic achievement. Measurement & Evaluation in Counseling & Development, 35, 35–48.

Roelofs, J., Papageorgiou, C., Gerber, R. D., Huibers, M., Peeters, F., & Arnoud, A. (2007). On the links between self-discrepancies, rumination, metacognitions, and symptoms of depression in undergraduates. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 1295–1305.

Scaini, S., Palmieri, S., Caselli, G., & Nobile, M. (2020). Rumination thinking in childhood and adolescence: A brief review of candidate genes. Journal Affective Disorders, 280, 197–202.

Shafran, R., & Mansell, W. (2001). Perfectionism and psychopathology: A review of research and treatment. Clinical Psychology Review, 21, 879–906.

Slaney, R. B., Mobley, M., Trippi, J., Ashby, J. S, & Johnson, D. G. (1996). Almost Perfect Scale-Revised. Unpublished manuscript. The Pennsylvania State University, State College.

Slaney, R. B., Rice, K. G., Mobley, M., Trippi, J., & Ashby, J. S. (2001). The revised Almost Perfect Scale. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 34, 130–145.

Smith, M., Sherry, S. B., Mc Larnon, M. E., Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Saklofske, D. H., & Etherson, M. (2018a). Why does socially prescribed perfectionism place people at risk for depression? A five- month, two-wave longitudinal study of the perfectionism social disconnection model. Personality and Individual Differences, 134, 49–54.

Smith, M. M., Vidovic, V., Sherry, S. B., Stewart, S. H., & Saklofske, D. H. (2018b). Perfectionistic concerns confer risk for anxiety symptoms: A meta-analysis of 11 longitudinal studies. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 31, 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2017.1384466.

Smith, M. M., Sherry, S. B., Chen, S., Saklofske, D. H., Mushquash, C., Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2018c). The perniciousness of perfectionism: A meta-analytic review of the perfectionism- suicide relationship. Journal of Personality, 86, 522–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12333.

Smith, M. M., Sherry, S. B., Vidovic, V., Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (2020). Why does perfectionism confer risk for depressive symptoms? A meta-analytic test of the mediating role of stress and social disconnection. Journal of Research in Personality, 86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2020.103954.

Stoeber, J. (2018). Perfectionism. In V. Zeigler-Hill & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. Springer.

Stoeber, J., & Otto, K. (2006). Positive conceptions of perfectionism: Approaches, evidence, challenges. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(4), 295–319.

Trapnell, P. D., & Campbell, J. D. (1999). Private self-consciousness and the five-factor model of personality: Distinguishing rumination from reflection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(2), 284–304.

Tremblay, I., Beaulieu, Y., Bernier, A., Crombez, G., Laliberte, S., & Thibault, P. (2008). Pain catastrophizing scale for francophone adolescents: A preliminary validation. Pain Research and Management, 13(1), 19–24.

Watkins, E., & Baracaia, S. (2001). Why do people ruminate in dysphoric moods? Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 723–734.

Watkins, M., & Moulds, M. (2005). Positive beliefs about rumination in depression, a replication and extension. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 73–82.

Wells, A., & Matthews, G. (1994). Attention and emotion: A clinical perspective. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Wells, A., & Matthews, G. (1996). Modelling cognition in emotional disorder: The S-REF model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 881–888.

Acknowledgments

We thank the clinicians and researchers from our institution for their contribution to this research project. We thank Juan Martín Gómez Penedo for reading the draft and contributing with many insightful methodological suggestions. Finally, we express our gratitude to all the participants in this study.

Credit Author Statement

Lorena De Rosa: Investigation and writing original draft.

Mariana C. Miracco: Project administration, writing, review and editing.

Marina S. Galarregui: Investigation, data analysis, visualization and editing.

Eduardo G. Keegan: Supervision, review and editing.

Funding

This project received financial support from the Universidad de Buenos Aires (UBACyT 20020130100863BA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

The study was assessed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Research of the Facultad de Psicología, Universidad de Buenos Aires.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Animal Rights This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

Lorena De Rosa, Mariana C. Miracco, Marina S. Galarregui and Eduardo G. Keegan declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

De Rosa, L., Miracco, M.C., Galarregui, M.S. et al. Perfectionism and rumination in depression. Curr Psychol 42, 4851–4861 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01834-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01834-0