Abstract

Rumination has been studied extensively as a transdiagnostic variable. The present study explored the relationship between rumination, perfectionism, self-compassion, depression, and anxiety severity in forty-nine adults, with a primary diagnosis of an anxiety disorder. They were assessed on the Ruminative Response Scale of the Response Style Questionnaire, Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale-Short form, Self-compassion scale, the Overall Anxiety Severity Scale, and the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Rumination was positively associated with all three dimensions of perfectionism, depression, and anxiety severity, and was negatively associated with self-compassion. Both socially prescribed perfectionism and self-compassion predicted rumination, and rumination was a significant predictor of depression and anxiety severity. Mediation analysis indicated that rumination mediated the relationship between socially prescribed perfectionism and depression severity. These findings reiterate our understanding of the role of transdiagnostic factors, such as, rumination, and perfectionism in anxiety disorders and the significance of self-compassion-based interventions in the alleviation of anxiety and depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anxiety disorders are characterized by an affective response of fear, autonomic arousal, hypervigilance, and behavioral disturbances in the form of avoidance and safety behaviors. Anxiety disorders are highly prevalent and contribute significantly to the global disease burden (Vos et al., 2020). In India, the National mental health survey reported the lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders to be 3.70% indicating that 3.7% of the Indian population has had an anxiety disorder at some point in their life (Gautham et al., 2020). Psychiatric comorbidity is common in persons with anxiety disorders, with depression being the most common comorbid condition (Kessler et al., 2005). Anxiety disorders have a significant negative impact on both functioning and quality of life (Birnbaum et al., 2010; Sudhir et al., 2012). The presence of shared vulnerability factors across anxiety and mood disorders was proposed by Barlow and colleagues (Barlow & Di Nardo, 1991; Zinbarg & Barlow 1996) and is supported by recent literature, suggesting that multiple disorders may share certain common diagnostic factors, termed as transdiagnostic (Sloan et al., 2017; Wahl et al., 2019).

Rumination as a Transdiagnostic Process

Some of the transdiagnostic processes identified across psychological disorders include rumination and perfectionism. Ruminative responses include behaviours and thoughts with an increased focus on and repetitive negative thinking about one’s symptoms, problems, distress, and feelings and rumination is important in both the onset and maintenance of emotional disorders (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991; Watkins, 2008). Rumination is thus considered as one form of repetitive negative thinking. Evidence for rumination as a transdiagnostic process comes from studies that suggest that an elevated level of repetitive negative thinking (RNT) is present in depression, anxiety and related disorders, insomnia, substance abuse, and personality disorders (Baer et al., 2012; Ehring & Watkins, 2008; McLaughlin & Nolen- Hoeksema, 2011; Rukmini, Sudhir & Bada Math, 2014).

Nolen-Hoeksema and Watkins (2011) proposed a model to explain the role of RNT in the development of various psychological disorders. In this model, RNT is said to act as a proximal risk factor in the background of multiple distal risk factors such as trauma, authoritarian parenting style, and biological factors. These distal factors determine the development of a tendency towards RNT through various cognitive and behavioral processes. In addition, certain moderators influence the development of the trajectory of an individual with a tendency for RNT, depending on their environmental context. Thus RNT as a transdiagnostic risk factor results in different clinical conditions, through differing pathways.

Meta-analytic studies indicate strong associations of rumination with symptoms of anxiety and depression (Olatunji et al., 2013), and rumination has been conceptualized as a risk factor in itself, for negative affect, distress, and impairment in problem-solving. The role of rumination as a mediator in the relationship between other vulnerability factors, such as negative cognitive styles, and mental health outcomes has been examined across studies (Spasojevi´c & Alloy, 2001; Robinson & Alloy 2003). This relationship may be better understood when rumination is examined as an emotion regulation strategy, with avoidance of emotion processing, leading to increased negative affect and behavioral outcomes (Luca, 2019). Rumination has also been conceptualized as an attempt toward goal attainment, aiding in effective self-regulation and an attempt at problem-solving when there is a perceived discrepancy between the current and desired state (Martin & Tessser, 1996a, 1996b). It has demonstrated large effect sizes in its relationship with various psychological disorders when compared with other emotion regulation strategies such as avoidance, acceptance, suppression, and reappraisal (Aldao et al., 2010).

Perfectionism and Rumination

In addition to negative mental health outcomes, rumination is also associated with elevated levels of maladaptive perfectionism (Flett et al., 2002; Frost et al., 1990; Xie et al., 2019). The transdiagnostic nature of perfectionism and its role in psychological disorders is well documented (Lenton-Brym & Antony, 2020). As a multi-dimensional construct, perfectionism comprises three dimensions, self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially prescribed perfectionism (Hewitt & Flett, 1991; Flett et al., 1995). Rumination in the context of perfectionism involves negative self-appraisal and self-criticality. The brooding dimension of rumination is an important mechanism implicated in the association between perfectionism and depression (Flett et al., 2016; O’Connor, O’Connor & Marshall, 2007; Rukmini et al., 2014; Short & Mazmanian, 2013). Further, the role of specific dimensions of perfectionism as a vulnerability to depression and the contribution of rumination is extensively discussed in literature (Blankstein & Lumley, 2008; Di Schiena, Luminet, Philippot, & Douilliez, 2012; Macedo et al., 2014).

Self-compassion and Rumination

Both rumination and maladaptive perfectionism involve excessive self-criticality, negative self-evaluation, and reduced self-compassion resulting in negative affect, and difficulties in self-acceptance. Self-compassion has been researched extensively in the context of psychological disorders and involves kindness towards self in the face of failures, feelings of oneness with others, recognizing one’s experiences as part of a common human experience, and acceptance of one’s negative experiences and feelings ((Neff, 2003a).

Self-compassion is likely to buffer the impact of anxiety and depression in several ways, including reducing negative self-evaluation (Bluth & Neff, 2018; Neff et al., 2007), through its positive effects on unproductive repetitive thinking (Raes, 2010), reducing self-criticality and negative self-appraisal. Self-compassion also enhances positive feelings of acceptance and kindness. Lower self-compassion has been associated with greater anxiety severity in clinical samples (Roemer et al., 2008; Wetterneck et al., 2013), and greater self-compassion is linked with lower levels of rumination, perfectionism, and fear of failure (Neff, 2003a; Neff et al., 2005; Neff & Vonk, 2009).

Rumination has been explored recently as a mediator of the relationship between self-compassion and depression across clinical populations (Johnson & O’Brien, 2013; Krieger et al., 2013; Hodgetts et al., 2020). The self-compassion-anxiety relationship is mediated by rumination and worry (Raes, 2010; Brown et al., 2019). These observations on the relationship between rumination, self-compassion, and anxiety provide support for the possibility that rumination might mediate the relationship between self-compassion and negative affect (Allen & Knight, 2005; Leary et al., 2007).

There is considerable literature on the role of rumination as a mediator of the perfectionism-psychological distress link. However, we could identify only two published studies that specifically examine this indirect pathway in a clinical sample (Smith et al., 2020; Egan et al., 2014), highlighting the need to explore these relationships in the same. Currently, there are no published studies from India on the mediating role of rumination in clinical samples. Previous studies in Indian samples highlight the role of vulnerability factors such as perfectionism in social phobia and depression (Jain & Sudhir, 2010; Mathew et al., 2014; Rukmini et al., 2014). Examining the role of rumination in this relationship between perfectionism, self-compassion, and anxiety/depression will have important clinical implications for planning interventions. Further, to the best of our knowledge, only two studies have directly tested the role of rumination as mediating the effects of self-compassion on anxiety, in a sample of undergraduates and breast cancer survivors (Raes, 2010; Brown et al., 2019), and only one existing study that has explored this in a clinical population with depression (Kreiger et al., 2013). Overall, although rumination is a highly prevalent vulnerability factor across clinical disorders, there is a dearth of empirical studies examining the mediating role of rumination in clinical samples. Examining rumination as a mediator of the relation of perfectionism and self-compassion to anxiety and depressive symptoms could therefore clarify its role in symptom severity in persons with anxiety disorders, and the relevance of targeting these cognitive processes in treatment.

Current Investigation

We studied rumination as a cognitive process and the relationship between rumination, perfectionism, self-compassion, and the severity of anxiety and depression in persons with anxiety disorders. We further examined rumination as a mediator in the relationship between perfectionism and depression, and between self-compassion and the severity of anxiety. In line with previous literature, we hypothesized that rumination would mediate the relationship between the trait variables and symptom severity.

Materials and Methods

Sample and Procedure

The sample included adult patients, aged 18–50 years, who were screened for eligibility and recruited from the outpatient services of a tertiary mental health care centre in Southern India. Inclusion criteria were a primary diagnosis of an anxiety disorder as per ICD-10 (F40-42), and the ability to read and comprehend English. Patients were recruited based on the file diagnosis given by a trained clinician and further confirmed by the first author using the MINI-Plus (Sheehan et al., 1998). Patients with a primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder, severe depression with psychotic symptoms, current substance dependence, and recent exposure to psychotherapy were excluded. Of the 56 patients who were screened for eligibility, 7 did not meet the study criteria, thus 49 patients were recruited. All measures were administered individually, in English by the first author, who also conducted the clinical interviews. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institute Ethics Committee. All participants provided written informed consent prior to their participation in the study.

Measures

Mini- International Neuropsychiatric Interview Plus (M.I.N.I.– Plus; Sheehan & Lecrubier, 1998)

This brief structured interview is designed to assess the presence or absence of major adult Axis I disorders as identified by DSM-IV and ICD − 10 and was administered to confirm the diagnosis of an anxiety disorder and rule out other major clinical disorders, listed as exclusion criteria. The MINI-Plus has good psychometric properties and is often used as a diagnostic tool in psychiatry (Pinninti et al., 2003).

The Ruminative Response Scale of the Response Style Questionnaire (RRS; Nolen- Hoeksema & Morrow‚ 1991)

The 22-item scale of the RSQ was used to assess the tendency to think about one’s feelings and symptoms of dysphoria. Responses are rated on a 4-point Likert scale, and participants indicate how often they, ‘think about how alone you feel, and ‘Analyze recent events to try to understand why they are depressed’. It has good internal consistency and adequate test-retest reliability (0.90 and 0.67 respectively).Cronbach alpha values for the RRS range from 0.88 to 0.92 (Luminet, 2004). Cronbach alpha for the RRS in the present sample was 0.86.

Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale- Short form (MPS-SF; Hewitt, Habke et al., 2008)

The MPS-Short form (MPS-SF) is a 15-item measure, with three subscales namely self-oriented perfectionism, (e.g., One of my goals is to be perfect in everything I do), other-oriented perfectionism (e.g., I have high expectations for the people who are important to me), and socially prescribed perfectionism (e.g., my family expects me to be perfect). Responses are rated on a 7-point scale, indicating the degree of agreement with the items. Only the subscale scores were used for interpretation. The MPS-SF has good correlations with the original version, MPS (Stoeber, 2016). The Cronbach alpha reliabilities for the subscales range from 0.75 to 0.85 (Hewitt et al., 2008). The MPS has also demonstrated good validity in studies ranging from community to clinical samples (Hewitt & Flett, 2004). In this sample, the Cronbach alpha was 0.92.

The Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) (Neff, 2003b)

The 26-item Self-Compassion Scale assesses six aspects of self-compassion namely, self-kindness (e.g., “When I’m going through a very hard time, I give myself the caring and tenderness I need”), self-judgment (e.g., “I’m intolerant and impatient toward those aspects of my personality I don’t like”), common humanity (e.g., “When things are going badly for me, I see the difficulties as part of life that everyone goes through”), isolation (e.g., “When I’m feeling down, I tend to feel like most other people are probably happier than I am”), mindfulness (e.g., “When I’m feeling down I try to approach my feelings with curiosity and openness”), and over-identification (e.g., “When I fail at something important to me I become consumed by feelings of inadequacy”). In the present study, a total self-compassion score was considered. Adequate validity and reliability are reported ((Neff, 2003b). SCS had a Cronbach alpha of 0.81 in the present sample. The SCS has been used with a variety of populations and has demonstrated good internal reliability and validity (Allen et al., 2012; Neff & Pommier, 2013; Werner et al., 2012).

Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS; Norman Hami-Cissell, Means-Christensen & Stein, 2006)

The OASIS is a 5-item self-report measure that assesses the severity and impairment associated with multiple anxiety disorders. It includes frequency, and intensity of anxiety symptoms, avoidance, and functional impairment associated with anxiety. Respondents are instructed to consider a variety of experiences such as panic attacks, worries, and flashbacks, and to consider all of their anxiety symptoms when responding. It is a reliable and valid instrument. Its validity has been demonstrated in both community (Norman et al., 2011, 2013) and clinical samples (Campbell-Sills et al., 2008). Cronbach’s alpha in this sample was 0.82.

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996)

The BDI-II is a widely used measure of the severity of depression and assesses cognitive, affective, and somatic components of depression, with 21 items, rated on a 0- 3-point scale. It has reported good validity and reliability (Beck et al., 1996; Gebrie, 2020) in different populations (van Noorden et al., 2012; Wang & Gorenstein, 2013; Subica et al., 2014). The scale had a Cronbach alpha of 0.92 in this sample.

Data Analysis

Data were analysed using the Statistical Program for Social Sciences 20.0 (SPSS) for Windows. Bivariate correlations were carried out between rumination, perfectionism, self-compassion, the severity of anxiety, and depression. Regression analysis was used to examine the predictors of rumination, depression, and anxiety severity. Mediation analysis was conducted using Hayes’ PROCESS macro (2013).

Results

Sample Description

The average age of the sample was 30 years (S.D.= 6.72 years). There were more males (71%) than females in the sample. The majority were graduates, employed, with more than half the sample being married, and living in nuclear families. There was a marginally higher number of patients with social phobia (n = 15) followed by obsessive-compulsive disorder (n = 12), generalized anxiety disorder (n = 11), panic disorder (n = 6) specific phobia (n = 3), and agoraphobia (n = 2) (Table 1).

Relationship Between Rumination, Perfectionism, Self-compassion, Anxiety Severity, and Depression

Bivariate correlations between variables were examined (Table 2). Rumination was positively associated with self-oriented (SOP; p < 0.05), other-oriented (OOP; p < 0.001), and socially prescribed perfectionism (SPP; p < 0.001) depression (p < 0.001) and anxiety severity (p < 0.05), and had a significant negative correlation with self-compassion. Scores on MPS-SF subscales- SOP (p < 0.001) and SPP (p < 0.05) were significantly negatively correlated with self-compassion. The subscales of perfectionism had low positive correlations with depression. Self-compassion was negatively correlated with anxiety severity (p < 0.05).

Mediation Analysis

Hayes’ (2013) PROCESS (Model 4) macro was used to examine rumination as a mediator of the relationship between socially prescribed perfectionism and depression, and between self-compassion and anxiety severity. The bootstrapping procedure further tests for indirect effects through multiple sampling from original data, and then tests for mediational analyses through each of these. The significance of these indirect effects is tested through the generation of confidence intervals. A significant indirect effect (p < 0.05) is one wherein the 95% confidence interval does not contain zero.

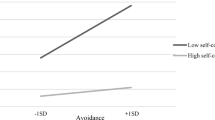

The bootstrap analysis procedure (Preacher & Hayes, 2004) was used to test for the indirect effects of socially prescribed perfectionism and self-compassion on depression and anxiety severity respectively, through the potential mediator, rumination. We considered these two models for the mediating effects of rumination, involving outcomes of depression and anxiety severity, with independent variables perfectionism and self-compassion respectively (Fig. 1). In the first model, the effects of rumination (RRS total) as a mediator on the relationship between socially prescribed perfectionism (HFPS- SP) and depression (BDI-II) were assessed. In the second model, the effects of rumination as a mediator between self-compassion (SCS) and anxiety severity (OASIS) were further explored. The SPSS bootstrapping script was used with 5000 bootstrap resamples estimating a 95% confidence interval for these indirect effects. In model 1, the indirect effect of socially prescribed perfectionism on depression via rumination was significant: effect = 0.285, bootstrapped SE = 0.119, 95% CI [0.072, 0.542]. For model 2, the indirect effects of self-compassion on anxiety severity via rumination were not significant: effect = -0.021, bootstrapped SE = 0.0193, 95% CI [-0.0678, 0.0059]. Our results indicate that rumination mediates the relationship between socially prescribed perfectionism and depression, however, it did not mediate the relationship between self-compassion and anxiety severity.

Discussion

We explored the relationship between rumination, perfectionism, self-compassion, and symptom severity in persons with anxiety disorders, and the role of rumination as a mediator in the association between, perfectionism and depression, and self-compassion and anxiety severity.

The demographics of the sample are largely consistent with other clinical studies from India and suggest that patients with anxiety disorders present for treatment as young adults, with more males than females seeking treatment (Jain & Sudhir, 2010; Selvikumari et al., 2012).

In keeping with existing literature, our findings indicate that higher levels of rumination are associated with greater perfectionism, severity of depression and anxiety, and lower self-compassion. A higher perfectionism was associated with lower self-compassion and these findings are in line with the response style theory of rumination that posits rumination to be a cognitive vulnerability associated with the onset of anxiety and depressive symptoms. Further, when rumination is used as a coping strategy, mood symptoms are exacerbated (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). Research has shown rumination to be a mediator in the relationship between perfectionism and general psychological distress, depression, and anxiety (Harris et al., 2008; Olson & Kwon, 2008; Randles et al., 2010).

Perfectionistic individuals are likely to engage in greater rumination over past events, with the content of ruminations being predominantly self-critical and this increases negative affect (Flett & Hewitt, 2007; O’Connor et al., 2007; Castro et al., 2017). This is in line with research on rumination as a maladaptive emotion regulation strategy, that perfectionistic individuals employ to cope with failures (Garnefski et al., 2001; Flett et al., 2018). Both self-oriented (SOP) and socially prescribed (SPP) perfectionism involve an aspect of self-criticality. Although SOP may be adaptive, when it occurs along with self-criticality it seems to be maladaptive. Thus, individuals with maladaptive perfectionism and self-criticality experience difficulty in accepting themselves and in being self-compassionate (Stoeber et al., 2020).

Consistent with the literature, rumination was found to mediate the association between SPP, the maladaptive dimension of perfectionism, and depression scores (Xie et al., 2019; Klibert et al., 2005). Martin and Tesser’s (1996) model of rumination explains how perfectionism leads to increased rumination due to perceived goal discrepancies, and unsatisfactory goal progress, resulting in perseverance on the discrepancy in an ineffective attempt to solve problems, and negative affect (Watkins, 2008). Specifically, individuals high on SPP who tend to pursue such goals for reasons such as extrinsic outcomes and others’ expectations, experience greater intrinsic conflict and maladaptive rumination (Thomsen et al., 2011).

Our findings are also in line with Olson and Kwon’s (2008) conceptualization of ‘ruminative perfectionism’ as a diathesis for depression, highlighting the need to target this “malicious combination” (Olson & Kwon, 2008, p.799) of rumination and perfectionism in patients with depression as well as anxiety disorders.

Self-compassion predicted rumination and anxiety severity. Individuals with lower self-compassion experience greater self-criticality, view their negative experiences in isolation, over-identify with their painful thoughts and feelings, and therefore tend to brood over negative thoughts and emotions (Ying, 2009). On the other hand, greater self-compassion has been associated with greater acceptance of one’s negative emotions and identification of difficult experiences as being universal, and thereby less rumination and event processing over one’s failures (Neff & Vonk, 2009; Raes, 2010; Blackie & Kocovski, 2017).

Self-compassion acts as a buffer against heightened rumination through effective emotion regulation, such as acceptance, and enables greater awareness of emotional experiences (Allen & Leary, 2010; Finlay-Jones, Rees, & Kane, 2015). Literature suggests that rumination can also be a mediator between self-compassion and anxiety (Leary et al., 2007; Raes, 2010; Blackie & Kocovski, 2018). Therefore, we attempted to test the role of rumination as a mediator of the link between self-compassion and anxiety severity. However, this mediation model was not significant in the present sample. Literature on the association between rumination and anxiety has yielded mixed findings, with some studies highlighting a stronger association between rumination and depression than with anxiety (Muris et al., 2004; Hong, 2007). Prior research has shown worry, another form of repetitive negative thinking, to especially mediate the relationship between self-compassion and anxiety (Raes, 2010). Therefore, future research could focus on the potential mediating role of other forms of RNT. These non-significant effects need to be interpreted with caution owing to the small sample size in the present study, and the cross-sectional nature of the assessment. Future work with longitudinal and multi-method designs and a larger sample size could help uncover these indirect pathways better. Additionally, other mechanisms that could contribute to the impact of self-compassion on symptom severity need to be explored.

Considering possible cultural factors that likely impact these variables, our results are in line with previous research indicating a higher prevalence of greater self-criticism and lower self-compassion in Asian cultures (Kitayama & Uchida, 2003; Neff et al., 2008; Yamaguchi et al., 2014). This could be related to the construal of self, based on ideas of interdependence and social conformity in Eastern cultures, and greater emphasis on socially prescribed standards (Khambaty & Parikh, 2022). Researchers have also argued that self-criticism in Eastern cultures could therefore be adaptive in maintaining interdependence and block out the impact of lower self-compassion on depression and anxiety (Heine, 2003; Kagitcibasi, 2005). In clinical practice, in the Indian setting, considering the role of socially prescribed perfectionism and self-compassion in the maintenance of symptoms and dysfunction could, thus, be useful.

Limitations and Future Research

Some of the limitations of this study were a small sample size that reduced the generalizability of the results. A larger sample size would help increase the power and show significant results where trends were found, including further testing of the mediating role of rumination in the self-compassion and anxiety severity link. Qualitative interviews in addition to self-report would have enriched the understanding of these findings. The cross-sectional nature of the present study did not allow for the examination of temporal changes in variables and a longitudinal design would be better able to address this. There is a need to replicate these findings across other clinical disorders, such as personality disorders, which could then strengthen our understanding of rumination as a transdiagnostic mediator. In addition to anxiety and depression, examining self-conscious emotions, such as shame and guilt, would further our knowledge of the nature of negative affect associated with rumination and low self-compassion.

Our sample was heterogenous, and representative of a treatment-seeking population, which helps understand these mechanisms across disorders. Our findings lend support to the need for process-based, transdiagnostic interventions that address shared mechanisms such as self-compassion, rumination, and perfectionism, in the management of anxiety and depressive disorders as well (Germer, 2009; Gilbert & Proctor, 2006; Watkins, 2015). These findings have particular significance in the Indian setting, where anxiety and depression contribute significantly to the disease burden for psychiatric disorders (Sagar et al., 2020).

In conclusion, our results provide evidence for the role of rumination in the perfectionism-depression link, and its association with self-compassion in anxiety disorders. Future research on establishing transdiagnostic factors as links through which different vulnerabilities lead to negative mental health outcomes could further provide targets for guiding therapeutic interventions.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available and the corresponding author [PMS], may be contacted for the details.

References

Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 217–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004

Allen, N. B., & Knight, W. E. J. (2005). Mindfulness, compassion for self, and compassion for others: Implications for understanding the psychopathology and treatment of depression. In P. Gilbert (Ed.), Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy (pp. 239–262). Hove: Routledge.

Allen, A. B., & Leary, M. R. (2010). Self-compassion, stress, and coping. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4, 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00246.x

Allen, A. B., Goldwasser, E. R., & Leary, M. R. (2012). Self-compassion and well-being among older adults. Self and Identity, 11(4), 428–453.

Baer, R. A., Peters, J. R., Eisenlohr-Moul, T. A., Geiger, P. J., & Sauer, S. E. (2012). Emotion-related cognitive processes in borderline personality disorder: A review of the empirical literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 359–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.03.002Q

Barlow, D. H. (1991). The diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder: Development, current status, and future directions. In R. M. Rapee, & D. H. Barlow (Eds.), Chrome anxiety. Generalized anxiety disorder and mixed anxiety-depression (18 vol., pp. 95–91). New York: Guilford Press. Di.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Beck Depression Inventory—Second Edition manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation.

Birnbaum, H. G., Kessler, R. C., Kelley, D., Ben-Hamad, R., Joish, V. N., & Greenberg, P. E. (2010). Employer burden of mild, moderate, and severe major depressive disorder: Mental Health Services utilization and costs, and work performance. Depression and Anxiety, 27, 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20580

Blackie, R. A., & Kocovski, N. L. (2018). Examining the Relationships among Self-Compassion, Social anxiety, and Post-Event Processing. Psychological Reports, 121, 669–689.

Blankstein, K. R., & Lumley, C. H. (2008). Multidimensional perfectionism and ruminative brooding in current dysphoria, anxiety, worry, and anger. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 26(3), 168–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-007-0068-z

Bluth, K., & Neff, K. (2018). New frontiers in understanding the benefits of self-compassion. Self and Identity, 17, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2018.1508494

Brown, S. L., Hughes, M., Campbell, S., & Cherry, M. G. (2019). Could worry and rumination mediate relationships between self-compassion and psychological distress in breast cancer survivors? Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2399

Campbell-Sills, L., Norman, S., Craske, M., Sullivan, G., Lang, A., Chavira, D., Bystritsky, A., & Stein, M. (2008). Validation of a brief measure of anxiety-related severity and impairment: The overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS). Journal of Affective Disorders, 112, 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.03.014

Castro, J., Soares, M. J., Pereira, A. T., & Macedo, A. (2017). Perfectionism and negative/positive affect associations: The role of cognitive emotion regulation and perceived distress/coping. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 39(2), 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1590/2237-6089-2016-0042

Di Schiena, R., Lumineta, O., Philippot, P., & Douilliez, C. (2012). Adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism in depression: Preliminary evidence on the role of adaptive and maladaptive rumination. Personality and Individual Differences, 53, 774–778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.05.017

Egan, S. J., Hattaway, M., & Kane, R. T. (2014). The relationship between perfectionism and rumination in post-traumatic stress disorder. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 42(2), 211.

Ehring, T., & Watkins, E. R. (2008). Repetitive negative thinking as a Transdiagnostic process. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 1(3), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1680/ijct.2008.1.3.192

Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2007). Cognitive and self-regulation aspects of perfectionism and their implications for treatment: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 25(4), 227–236.

Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., & Martin, T. R. (1995). Dimensions of perfectionism and procrastination. In J. R. Ferrari, J. L. Johnson, & W. G. McCown (Eds.), Procrastination and task avoidance: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 113–136). New York: Plenum Press.

Flett, G., Madorsky, D., Hewitt, P., & Heisel, M. (2002). Perfectionism cognitions, rumination, and psychological distress. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 20, 33–47.

Flett, G. L., Nepon, T., & Hewitt, P. L. (2016). Perfectionism, worry, and rumination in Health and Mental Health: A review and a conceptual Framework for a cognitive theory of perfectionism. Perfectionism, Health, and Well-being: Springer International Publishing.

Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Nepon, T., & Besser, A. (2018). Perfectionism cognition theory: The cognitive side of perfectionism. In J. Stoeber (Ed.), The psychology of perfectionism: Theory, research, applications (pp. 89–110). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V., & Spinjoven, P. (2001). Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation, and emotional problems. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 1311–1327.

Gautham, M. S., Gururaj, G., Varghese, M., Benegal, V., Rao, G. N., Kokane, A., & Shibukumar, T. M. (2020). The National Mental Health Survey of India (2016): Prevalence, socio-demographic correlates and treatment gap of mental morbidity. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(4), 361–372.

Gebrie, M. H. (2020). An analysis of the Beck Depression Inventory. 2nd edition (BDI-II). Global Journal of Endocrinological Metabolism, 2 (2).

Germer, C. K. (2009). The mindful path to self-compassion: Freeing yourself from destructive thoughts and emotions. The Guilford Press.

Gilbert, P., & Procter, S. (2006). Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and Self-Criticism: Overview and pilot study of a Group Therapy Approach. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 13, 353–379.

Harris, P., Pepper, C., & Maack, D. (2008). The relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and depressive symptoms: The mediating role of rumination. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.07.011

Heine, S. J. (2003). An exploration of cultural variation in self-enhancing and self-improving motivations. In V. Murphy-Berman, & J. J. Berman (Eds.), Cross-cultural differences in perspectives on the self (pp. 118–145). University of Nebraska Press.

Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 456–470.

Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (2004). Multidimensional perfectionism scale (MPS): Technical manual. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems.

Hewitt, P. L., Habke, A., Lee-Baggley, D. L., Sherry, S. B., & Flett, G. L. (2008). The impact of perfectionistic self-presentation on the cognitive, affective, and physiological experience of a clinical interview. Psychiatry: Interpersonal & Biological Processes, 71, 93–122.

Hodgetts, J., McLaren, S., Bice, B., & Trezise, A. (2020). The relationships between self-compassion, rumination, and depressive symptoms among older adults: The moderating role of gender. Aging & Mental Health, 1–10.

Hong, R. Y. (2007). Worry and rumination: Differential associations with anxious and depressive symptoms and coping behaviour. Behavior Research and Therapy, 45, 277–290.

Jain, M., & Sudhir, P. M. (2010). Perfectionism in social phobia. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 3(4), 216–222.

Johnson, E. A., & O’Brien, K. A. (2013). Self-compassion soothes the savage ego-threat system: Effects on negative affect, shame, rumination, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 32(9), 939–963.

Kagitcibasi, C. (2005). Autonomy and relatedness in cultural context: Implications for self and family. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, 36(4), 403–422.

Kessler, R., Chiu, W., Demler, O., & Walters, E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and Comorbidity of 12-Month DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(June), https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617

Khambaty, M., & Parikh, R. M. (2022). Cultural aspects of anxiety disorders in India. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 19(2), 117–126.

Kitayama, S., & Uchida, Y. (2003). Explicit self-criticism and implicit self-regard: Evaluating self and friend in two cultures. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 476–482.

Klibert, J. J., Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J., & Saito, M. (2005). Adaptive and maladaptive aspects of self-oriented versus socially prescribed perfectionism. Journal of College Student Development, 46, 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2005.0017

Krieger, T., Altenstein, D., Baettig, I., Doerig, N., & Holtforth, M. G. (2013). Self-compassion in depression: Associations with depressive symptoms, rumination, and avoidance in depressed outpatients. Behavior therapy, 44(3), 501–513.

Leary, M. R., Tate, E. B., Adams, C. E., Allen, A. B., & Hancock, J. (2007). Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: The implications of treating oneself kindly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 887–904. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.887

Lenton-Brym, A. P., & Antony, M. M. (2020). Perfectionism. In J. S. Abramowitz & S. M. Blakey (Eds.), Clinical handbook of fear and anxiety: Maintenance processes and treatment mechanisms (p. 153–169). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000150-009

Luca, M. (2019). Maladaptive rumination as a transdiagnostic mediator of vulnerability and outcome in psychopathology. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(3), 314.

Luminet, O. (2004). Measurement of depressive rumination and Associated Constructs. Depressive Rumination, 187.

Macedo, A., Marques, M., & Pereira, A. (2014). Perfectionism and psychological distress: A review of the cognitive factors. International Journal of Clinical Neurosciences and Mental Health, 1. https://doi.org/10.21035/ijcnmh.2014.1.6

Martin, L., & Tesser, A. (1996). Some ruminative thoughts. In R. S. Wyer (Vol (Ed.), Ed.), ruminative thoughts: Advances in social cognition (pp. 1–47). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum: Vol. IX.

Mathew, M., Sudhir, P. M., & Mariamma, P. (2014). Perfectionism, interpersonal sensitivity, dysfunctional beliefs, and automatic thoughts: The temporal stability of personality and cognitive factors in depression. International Journal of Mental Health, 43(1), 50–72.

McLaughlin, K. A., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2011). Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor in depression and anxiety. Behavior Research and Therapy, 49, 186–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.12.006

Muris, P., Roelofs, J., Meesters, C., & Boomsma, P. (2004). Rumination and worry in nonclinical adolescents. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 28, 539–554.

Neff, K. D. (2003a). Self-Compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward Oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

Neff, K. D. (2003b). Development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2, 223–250.

Neff, K. D., & Pommier, E. (2013). The relationship between self-compassion and other-focused concern among college undergraduates, community adults, and practicing meditators. Self and Identity, 12(2), 160–176.

Neff, K. D., & Vonk, R. (2009). Self-compassion versus global self-esteem: Two different ways of relating to oneself. Journal of Personality, 77, 23–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00537.x

Neff, K. D., Hsieh, Y. P., & Dejitterat, K. (2005). Self-compassion, achievement goals, and coping with academic failure. Self and Identity, 4(3), 263–287.

Neff, K. D., Kirkpatrick, K. L., & Rude, S. S. (2007). Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.004

Neff, K. D., Pisitsungkagarn, K., & Hsieh, Y. P. (2008). Self-compassion and self-construal in the United States, Thailand, and Taiwan. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 39(3), 267–285.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.569

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 115–121.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Watkins, E. R. (2011). A Heuristic for developing transdiagnostic models of psychopathology: Explaining multifinality and divergent trajectories. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6), 589–609. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611419672

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x

Norman, S. B., Cissell, S. H., Means-Christensen, A. J., & Stein, M. B. (2006). Development and validation of an overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS). Depression Anxiety, 23(4), 245–249.

Norman, S. B., Campbell-Sills, L., Hitchcock, C. A., Sullivan, S., Rochlin, A., Wilkins, K. C., & Stein, M. B. (2011). Psychometrics of a brief measure of anxiety to detect severity and impairment: The overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS). Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45(2), 262–268.

Norman, S. B., Allard, C. B., Trim, R. S., Thorp, S. R., Behrooznia, M., Masino, T. T., & Stein, M. B. (2013). Psychometrics of the overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS) in a sample of women with and without trauma histories. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 16(2), 123–129.

O’Connor, D. B., O’Connor, R., & Marshall, R. (2007). Perfectionism and psychological distress: Evidence of the mediating effects of rumination. European Journal of Personality, 21(4), 429–452.

Olatunji, B. O., Naragon-Gainey, K., & Wolitzky-Taylor, K. B. (2013). Specificity of rumination in anxiety and depression: A multimodal meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 20(3), 225–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12037

Olson, M. L., & Kwon, P. (2008). Brooding perfectionism: Refining the Roles of Rumination and Perfectionism in the etiology of Depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32, 788–802. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-007-9173-7

Pinninti, N. R., Madison, H., Musser, E., & Rissmiller, D. (2003). MINI International Neuropsychiatric schedule: Clinical utility and patient acceptance. European Psychiatry, 18(7), 361–364.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods Instruments & Computers, 36(4), 717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206553

Raes, F. (2010). Rumination and worry as mediators of the relationship between self-compassion and depression and anxiety. Personality and Individual Differences, 48, 757–761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.01.023

Randles, D., Flett, G., Nash, K., Mcgregor, I., & Hewitt, P. (2010). Dimensions of perfectionism, behavioral inhibition, and rumination. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 83–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.03.002

Robinson, M. S., & Alloy, L. B. (2003). Negative cognitive styles and stress-reactive rumination interact to Predict Depression: A prospective study. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27, 275–291. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023914416469

Roemer, L., Lee, J. K., Salters-Pedneaulty, K., Erisman, S. M., Orsillo, S. M., & Mennin, D. S. (2008). Mindfulness and emotion regulation difficulties in generalized anxiety disorder: Preliminary evidence for independent and overlapping contributions. Behavior Therapy, 40(2), 142–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2008.04.001

Rukmini, S., Sudhir, P. M., & Math, S. B. (2014). Perfectionism, emotion regulation and their relationship to negative affect in patients with Social Phobia. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 36(3), 239–245. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.135370

Sagar, R., Dandona, R., Gururaj, G., Dhaliwal, R. S., Singh, A., Ferrari, A., & Dandona, L. (2020). The burden of mental disorders across the states of India: The global burden of Disease Study 1990–2017. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(2), 148–161.

Selvikumari, R., Sudhir, P. M., & Mariamma, P. (2012). Perfectionism and interpersonal sensitivity in Social Phobia: The interpersonal aspects of perfectionism. Psychological Studies, 57(4), 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-012-0157-7

Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., & Dunbar, G. C. (1998). The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(Suppl 20), 22–33.

Short, M. M., & Mazmanian, D. (2013). Perfectionism and negative repetitive thoughts: Examining a multiple mediator model in relation to mindfulness. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(6), 716–721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.05.026

Sloan, E., Hall, K., Moulding, R., Bryce, S., Mildred, H., & Staiger, P. K. (2017). Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic treatment construct across anxiety, depression, substance, eating and borderline personality disorders: A systematic review. Clinical psychology review, 57, 141–163.

Smith, M. M., Sherry, S. B., Ray, C. M., Lee-Baggley, D., Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (2020). The existential model of perfectionism and depressive symptoms: Tests of Unique Contributions and Mediating Mechanisms in a sample of depressed individuals. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 38(1), 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282919877777

Stoeber, J. (2016). The psychology of perfectionism: Theory, research, applications. London: Routledge.

Stoeber, J., Lalova, A. V., & Lumley, E. J. (2020). Perfectionism, (self-) compassion, and subjective well-being: A mediation model. Personality and Individual Differences, 154, 109708.

Subica, A. M., Fowler, J. C., Elhai, J. D., Frueh, B. C., Sharp, C., Kelly, E. L., & Allen, J. G. (2014). Factor structure and diagnostic validity of the Beck Depression Inventory-II with adult clinical inpatients: Comparison to a gold-standard diagnostic interview. Psychological Assessment, 26(4), 1106–1115. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036998

Sudhir, P. M., Sharma, M. P., Mariamma, P., & Subbakrishna, D. K. (2012). Quality of life in anxiety disorders: Its relation to work and social functioning and dysfunctional cognitions: An exploratory study from India. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 5(4), 309–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2012.05.006

Thomsen, D. K., Tønnesvang, J., Schnieber, A., & Olesen, M. H. (2011). Do people ruminate because they haven’t digested their goals? The relations of rumination and reflection to goal internalization and ambivalence. Motivation and Emotion, 35, 105–117.

van Noorden, M. S., van Fenema, E. M., van der Wee, N. J., Zitman, F. G., & Giltay, E. J. (2012). Predicting outcome of depression using the depressive symptom profile: The Leiden Routine Outcome Monitoring Study. Depression and Anxiety, 29(6), 523–530. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.21958

Vos, T., Lim, S. S., Abbafati, C., Abbas, K. M., Abbasi, M., Abbasifard, M., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2020). Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet, 396(10258), 1204–1222.

Wahl, K., Ehring, T., Kley, H., Lieb, R., Meyer, A., Kordon, A., & Schönfeld, S. (2019). Is repetitive negative thinking a transdiagnostic process? A comparison of key processes of RNT in depression, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and community controls. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 64, 45–53.

Wang, Y. P., & Gorenstein, C. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: A comprehensive review. Revista brasileira de psiquiatria (Sao Paulo Brazil: 1999), 35(4), 416–431. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2012-1048

Watkins (2008). Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychological Bulletin, 134(2), 163–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.163

Werner, K. H., Jazaieri, H., Goldin, P. R., Ziv, M., Heimberg, R. G., & Gross, J. J. (2012). Self-compassion and social anxiety disorder. Anxiety Stress & Coping, 25(5), 543–558.

Wetterneck, C. T., Lee, E. B., Smith, A. H., & Hart, J. M. (2013). Courage, self-compassion, and values in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 2, 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2013.09.002

Xie, Y., Kong, Y., Yang, J., & Chen, F. (2019). Perfectionism, worry, rumination, and distress: A meta-analysis of the evidence for the perfectionism cognition theory. Personality and Individual Differences, 139, 301–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.11.028

Yamaguchi, A., Kim, M. S., & Akutsu, S. (2014). The effects of self-construals, self-criticism, and self-compassion on depressive symptoms. Personality and individual differences, 68, 65–70.

Ying, Y. W. (2009). Contribution of self-compassion to competence and mental health in social work students. Journal of Social Work Education, 45, 309–323.

Zinbarg, R. E., & Barlow, D. H. (1996). Structure of anxiety and the anxiety disorders: A hierarchical model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 105(2), 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.105.2.181

Finlay-Jones, A.L., Rees, C.S., &; Kane, R.T. (2015). Self-Compassion, Emotion Regulation,and Stress among Australian Psychologists: Testing an Emotion Regulation Model of Self-Compassion Using Structural Equation Modeling. PLoS ONE, 10.

Funding

The first author was awarded a junior research fellowship from the University Grants Commission, India (Ref no. 460/ (NET-DEC.2015)), for her MPhil Program in Clinical Psychology and this research was part of the academic fulfillment of the programme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Compliance with ethical standards

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institute Ethics Committee.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in this research study.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Petwal, P., Sudhir, P.M. & Mehrotra, S. The Role of Rumination in Anxiety Disorders. J Rat-Emo Cognitive-Behav Ther 41, 950–966 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-023-00513-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-023-00513-2