Abstract

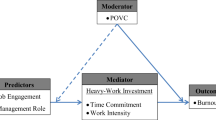

The purpose of this study is to examine the effect of frontline luxury service providers’ emotional labor induced burnout on their retaliatory behaviors in two contexts: within the organizational context (frontline luxury service providers’ work domain) and outside of the organizational context (frontline luxury service providers’ personal domain: when they become luxury service recipients). The moderating effects of extrinsic motivations (organizational rewards and social rewards) on the relationship between emotional labor and burnout is also explored. A total of 283 frontline luxury service providers participated in the survey. Structural equation modeling was employed to test the theoretical model. The results show that frontline luxury service providers’ burnout is positively related to retaliatory behaviors, both as providers and recipients of luxury services. Moreover, this study finds that only surface acting, not deep acting, is positively related to burnout in the context of luxury services. When it comes to moderation effect, only extrinsic motivation for organizational rewards is found to have a moderating effect on the relationship between deep acting and burnout. This study contributes to the literature by extending the scope of the domain of workplace burnout, from within organizational context to outside of the organizational context, based on the horizontal negative spillover effects. In this study, the authors make the first attempt to explore a new context of the luxury providers’ personal domain (when frontline luxury service providers become service recipients) in response to their workplace burnout.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Frontline service providers are the real face and voice of the company as they deliver the company’s promises and create images through direct customer interactions (Hartline & Ferrell, 1996; Som & Blackaert, 2015). They can deliver quality services with warmth and friendliness, even using attractive non-verbal cues such as positive facial expressions and body movement (Magnini, Baker, & Karande 2013). They must manage their emotions to display only those that are appropriate at the workplace. This management, referred to as emotional labor, is frequently observed in the service industry such as hotels, retail, casinos, and healthcare (Chen, Chang, & Wang 2019; Kim et al., 2012; Prentice, 2016). In particular, the luxury services sector demands higher levels of emotional labor from frontline service providers than the non-luxury sector because customers expect higher levels of service quality, including personalized services, an attractive physical appearance and communication skills—all of which require higher levels of emotional labor (Johansson & Naslund, 2009; Tracy, 2000). Due to high levels of emotional labor involved, frontline service providers suffer from occupational stress and burnout (Bono & Vey, 2005; Zapf et al., 2001). As burned out frontline service providers need to find a way to vent their negative feelings, they tend to engage in retaliatory behaviors. Such behaviors are observed in the organizational context such as workplace deviance behaviors or decreased work-related performance (Berry, Ones, & Sackett 2007; Fox & Spector, 1999; Jelinek & Ahearne, 2010). In either case, the effects of burnout are detrimental.

While extant literature focuses on the negative consequences of emotional labor mostly within the organizations, this study extends the scope beyond the organizational boundary by addressing how frontline luxury service providers react as luxury service recipients under the condition of workplace burnout. This is an interesting shift, from the organizational context to employee’s personal domain outside the organizational context, as daily practices at workplace are attributed to employees’ sense of self and dignity. This becomes further amplified among frontline service providers in the luxury services sector due to inequality of privilege between frontline service providers and customers. Therefore, this study aims to examine the effect of frontline luxury service providers’ emotional labor induced burnout on their resultant retaliatory behaviors (1) within organizational context (i.e. frontline luxury service providers’ work domain) and (2) outside of the organizational context (i.e. frontline luxury service providers’ personal domain: when they become luxury service recipients). This study also examines the moderating effects of two types of extrinsic motivations (organizational rewards and social rewards) on the relationship between emotional labor and burnout.

Theoretical Background and Literature Review

Frontline Service Providers in Luxury Services

In the past, the central value of luxury was often associated with a product of great craftsmanship, and the value was judged based on the goods itself, focusing on elements such as attraction, visibility, and symbolic elements (Ahn, Park, & Hyun 2018). Due to the elasticity of customer demand, the value of luxury has shifted to an “experience economy” (Lunardo & Mounague, 2019). This indicates that luxury service consumption involves emotional aspects such as sensory pleasure and emotion (Loureiro & Araujo, 2014). Customers seek luxury services that make positive affirmations about themselves and even help them manage stress effectively in their daily life.

Frontline luxury service providers are required to fulfill consumers’ needs through higher levels of customer care including personalization, anticipation, legitimation, resolution of needs, sincerity and authenticity, and availability of either visible or invisible physical labor (Sherman, 2002). Furthermore, frontline luxury service providers are expected to develop an emotional bond with their customers, which is beyond lavish attention (Sherman, 2007). The importance of physical appearance and attire of the frontline luxury service provider has also been highlighted in the luxury services industry as customers tend to positively associate such factors with the heightened level of perceived service quality (Quach, Jebarajakirthy, & Thaichon 2017). Due to the unique characteristics of the service industry such as inseparability of production and consumption, service firms are emphasizing providing positive attitudes and emotions by prescribing both implicit and explicit display rules during service encounters (Lee & Ok, 2012). While service quality and satisfaction are important in the service industry, they are more important in luxury service firms as customers expect higher service quality (Dubois, Czellar, & Laurent 2005). The roles of frontline service providers in luxury services are even more critical as the best luxury services are not standardized but customized (Brant, 2016). For these reasons, frontline luxury service providers are expected to experience higher levels of emotional stress from work than their counterparts, that is, non-luxury service providers (Sherman, 2007). Nevertheless, understanding the effect of emotional labor on luxury service providers is still limited (Godwyn, 2006). Thus, it is important to examine the impact of emotional labor on luxury service providers.

Emotional Labor: Surface Acting and Deep Acting

Emotional labor refers to “the management of feeling to create publicly observable facial and body display” (Hochschild, 1983, p. 7). Emotional labor has been widely described as a dynamic self-regulatory process that employees use to express their emotions by surface acting and deep acting, and constantly adjusting and monitoring their feelings during interactions with customers (Gabriel & Diefendorff, 2015). The core principle of emotional labor is the artificial manipulation of emotions to satisfy organizational needs according to the display rules (Qin, Young, Supekar, Uddin, & Menon, 2012).

Extant studies consider emotional labor as a bi-dimensional concept (i.e. surface acting and deep acting) (Grandey, 2000; Hochschild, 1983). Surface acting is an external emotional expression during which individuals practice “faking or amplifying emotions by displaying emotions not actually felt” (Groth, Hennig-Thurau, & Walsh 2009, p. 958). In surface acting, frontline service providers focus on managing outward emotional expressions to fulfill organizational display rules, while their inner feelings remain unchanged (Hochschild, 1983). With surface acting, frontline service providers consume psychological resources to suppress their inner feelings, thereby leading to loss of resources or ego depletion (Gradney, 2003; Weiss, Forkus, Contractor, & Schick, 2018). On the other hand, deep acting is an internal emotional modification when one “attempt[s] to modify felt emotions so that genuine emotional display follows” (Groth et al., 2009, p. 958). In deep acting, frontline service providers can modify their emotions to match their behavior or organizationally desired emotions. Frontline service providers with deep acting can activate cognitions to improve mood and follow the rules by displaying genuine emotion to customers (Chi & Grandey, 2019). For example, when dealing with angry passengers, flight attendants may feel frustrated and emotionally drained since they need to interact with them in a very friendly way. Those who adopt deep acting are likely to consider those customers as frightened first-time fliers; therefore, they understand and accept customers’ frustration. In this way, flight attendants can change their inner feelings from annoyance to emotional acceptance (Hochschild, 1983).

Consequence of Emotional Labor: Burnout

High intensity and frequency of interpersonal contact in the form of the verbal and non-verbal cues of frontline luxury service providers is required. This, in return, leads frontline luxury service providers to expose to situations requiring emotional regulation continuously. As frontline luxury service providers put more effort into regulating their emotions, it is likely to increase the loss of resources, which results in negative consequences such as burnout (Ashill & Rod, 2011). Burnout has been linked to a negative emotional reaction to one’s job that results from chronic exposure to a stressful work environment (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter 2001). Burnout is defined as a state of emotional exhaustion and emotional depletion that is dysfunctional for the employee and impacts on employees’ job-related outcomes such as job stress, job dissatisfaction, and job performance (Bakker & Heuven, 2006).

Previous research provides theoretical explanations about whether emotional labor contributes to burnout (Brotheridge & Lee, 2002). Studies find that deep acting preserves and promotes psychological resources (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Lee, Ok, Lee, & Lee 2018). Specifically, deep acting increases a sense of personal accomplishment and authenticity (Hülsheger & Schewe, 2011). Thus, it is expected that deep acting would require less emotional resources than surface acting, and would protect psychological resources against burnout. Empirical evidence supports this theoretical proposition that the use of surface acting is related to the symptoms of burnout (Lee et al., 2018; Totterdell & Holman, 2003). For example, Brotheridge and Grandey (2002) found that surface acting was positively related to emotional exhaustion, while deep acting showed almost no relationship. Totterdell and Holman (2003) also demonstrated that surface acting is more positively associated with burnout than deep acting. These researchers show that the more frequent service providers experience emotional dissonance, individuals are likely to report higher levels of burnout in their job. While these studies were conducted with service providers in the non-luxury services sector, our study focuses on the relationship between emotional labor and burnout among frontline service providers in the luxury services sector. The following hypotheses were developed:

-

H1a.

Frontline luxury service providers’ surface acting is positively related to their burnout in the workplace.

-

H2a.

Frontline luxury service providers’ deep acting is negatively related to their burnout in the workplace.

Consequences of Burnout

Retaliatory Behaviors within Work Domain as Frontline Service Providers: Workplace Deviance

Frustrating situational constraints in the work environment (e.g. high level of emotional labor, lack of autonomous) lead to negative emotional reactions (e.g. high levels of stress, burnout), thereby encouraging counterproductive behaviors (Fox & Spector, 1999). Frontline service providers, particularly in the luxury services sector, are likely to suffer from emotional laden stress while interacting with customers as a smaller number of customers seek higher levels of service quality, setting expectations of services that are difficult to fulfill. Since frontline luxury service providers do not always have control over the situation because of inadequate training, lack of supervisory support, role ambiguity, or other factors, they experience negative emotional responses such as frustration, anger, or anxiety. In return, they may voluntarily and intentionally engage in counterproductive work behaviors such as reduced levels of work-related morale, performance, and productivity (Phillips, Tan, & Julian 2006), service sabotage (Harris & Ogbonna, 2012), retaliation (Madupalli & Poddar, 2014), and even workplace deviant behaviors (Enwereuzor et al., 2017; Malik et al., 2019). This implies that frontline luxury service providers may accuse the organization, co-workers, and/or customers since either or all can be considered as the perceived cause of such negative feelings and this is one way to vent their negative feelings derived from burnout (Fox & Spector, 1999). Such behaviors are pervasive problems that create economic threats to the organization (Harris & Ogbonna, 2012). A large body of literature focuses on employees’ retaliatory behaviors in the organizational context: workplace deviance. Workplace deviance is defined as employees’ voluntary behavior that disconfirms organizational norms, threatens organizational and/or members’ well-being in the organizational context (Robinson & Bennett, 1995). Bennett and Robinson (2000) group workplace deviance into two forms: organizational deviance and interpersonal deviance. Organizational deviance refers to employees’ deviant behaviors which are non-interpersonal and sabotage the organization itself, such as theft and vandalism (Jelinek & Ahearne, 2010). Interpersonal deviance is defined as employees’ deviant behaviors that are interpersonal and harmful to individuals, including co-workers and colleagues, such as ridiculing co-workers and/or acting rudely with them (Berry et al., 2007). Burnout can provoke both types of workplace deviance behaviors – organizational deviance and interpersonal deviance – because it induces frustration, failure, anger, and lack of efficacy (Maslach & Goldberg, 1998). Given that the luxury services sector is fraught with emotional labor, organizational and interpersonal deviance is exacerbated when frontline luxury service providers experience burnout. Therefore, we hypothesize that higher burnout, higher will be organizational and interpersonal deviance behaviors.

-

H3a.

Frontline luxury service providers’ burnout is positively related to their organizational deviance behaviors.

-

H3.

Frontline luxury service providers’ burnout is positively related to their interpersonal deviance behaviors.

Retaliatory Behaviors outside of Work Domain as Service Recipients: Customer Retaliatory Behaviors

While a large body of literature focuses on the negative effect of burnout on the resultant behaviors such as workplace deviance within the same domain (i.e. job-related), the horizontal spillover theory explains that the impact of satisfaction/dissatisfaction of one domain can be carried over to another domain through permeable boundaries (Zedeck, 1992). The horizontal spillover effects can have both negative and positive forms across different domains (Sirgy, 2012). Since our study focuses on burnout, which obviously leads to negative outcomes, the scope of this paper is the negative spillover effect of burnout. Several researchers examine the effects between work and a variety of personal life domains such as home life (Leung, 2011), leisure (Furnham, 1991), and recreational situations (Diener & Larsen, 1984). There is also increasing evidence that work-related stressors such as burnout have a negative impact on an individual’s personal functioning as well (Maslach & Leiter, 2016). This clearly indicates that burnout has a negative spillover effect on the frontline service provider’s personal life outside the organizational context. Among the various domains outside of work, the domain in which frontline service providers become service recipients has been overlooked in the literature. There is increasing evidence that frontline service providers suffer from emotional labor since the nature of their job constantly requires them to interact with customers. The degree of emotional labor can be further amplified among frontline service providers in the luxury services sector due to privilege discrepancy between service providers and customers (Sherman, 2005). Yet, these frontline luxury service providers frequently become service recipients outside their job. In accordance with previous studies that have established the negative horizontal spillover of work-related stress such as burnout into personal life, negative horizontal spillover effects from burnout are likely to occur when frontline luxury service providers become luxury service recipients. A possible behavioral response is customer retaliatory behaviors as luxury service recipients.

Customer retaliation refers to customer’s behavioral efforts attempting to penalize and inconvenience a company that has caused damages to the customer (Grégoire & Fisher, 2008; Harris & Daunt, 2013). Customer retaliation is categorized into three forms: vindictive complaining, negative word-of mouth, and third-party complaining for gaining publicity (Grégoire & Fisher, 2008). Vindictive complaining is a direct form of customer retaliation when the customer directly accuses a company’s employee of inconvenience while both negative word-of-mouth and third-party complaining for gaining publicity are indirect forms of customer retaliation. The former is customers’ efforts to spread negative opinion to their acquaintances and family while the latter involves reaching out to a third-party organization such as an agency, media, or a complaint website (Harris & Daunt, 2013). Building on previous findings highlighting the negative spillover effects of work-related stress such as burnout on personal life domains such as reduced levels of personal life satisfaction, we argue that the higher the burnout from frontline luxury service providers, the more likely it is for them to engage in punitive customer retaliatory behaviors when receiving unsatisfactory services as luxury service recipients. Therefore, it is hypothesized that:

-

H4.

When frontline luxury service providers become the luxury service recipients, workplace burnout is positively related to their engagement in customer retaliatory behaviors.

Moderating Effects of Extrinsic Motivations for Organizational Rewards and Social Rewards

Self-determination theory provides a theoretical lens to explain how two forms of motivation (i.e. extrinsic vs. intrinsic) influence the adoption of labor strategies such as surface acting and deep acting (Deci & Ryan, 2004; Sisley & Smollan, 2012). While intrinsic motivation is more autonomous in nature than extrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation also varies considerably in its relative autonomy (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2000b). Deci and Ryan (1985) categorize extrinsic motivation into four forms along with the autonomy continuum range from low to high: external regulation (i.e. the least autonomous type of motivation – the individual is fully controlled by external incentives to gain rewards or avoid punishment), introjected regulation (i.e. partially internalized regulation – the individual is regulated to improve ego-involvement, feelings of value, or price or lessen guilt, anxiety, or shame), identified regulation (i.e. more autonomous type of extrinsic motivation – the individual values and consciously recognizes the regulation), and integrated regulation (i.e. the most autonomous form of extrinsic motivation – the individual identifies, evaluates, and assimilates the regulation with his/her own personal values, goals, and self).

Service providers with intrinsic motivation can enjoy the inherent pleasures of the job, while extrinsic motivation provides incentives and energy to achieve the goals set by the organization (Cossette & Hess, 2015). However, regardless of the inherent benefits of intrinsic motivation, the emotional labor involved in providing luxury service is essentially an externally driven intentional action that requires employees to regulate their emotions to reach a higher level of “organizational demand” (Rubin et al., 2005). This means that emotional labor in the luxury services sector is still considered unpleasant since it depletes personal resources and surrenders personal autonomy. Cossette (2014) argues that intrinsic motivation is not relevant to conduct emotional labor. In other words, one can regulate emotional labor based on external factors such as monetary rewards or supervisors’ support than by using one’s own psychological factors such as personal values. Following this line of reasoning, it can be claimed that emotional regulation is theoretically more relevant to extrinsic motivation than to intrinsic motivation in the context of this study.

Organizational rewards refer to visible extrinsic rewards provided by the organization such as pay, bonuses, and fringe benefits (Mottaz, 1985). Social rewards are defined as extrinsic rewards derived from the quality of interpersonal relationships such as friendly, helpful, and supervisory support (Mottaz, 1985). Service providers with a deep acting strategy make efforts to feel and display the required emotions (Ashforth & Humphrey, 1993). Therefore, they try to justify their actions as relevant to their internal values, loyalty to the organization, or a demonstration of good faith (Johnson & Spector, 2007). This implies that motivations for extrinsic rewards (i.e. organizational rewards or social rewards) can be even detrimental to them as such extrinsic motivations dilute their justification of engaging in deep acting.

On the other hand, service providers engage in surface acting either to receive rewards or to avoid punishment, implying that the locus of their motivation is externalized (Deci & Ryan, 2000). In other words, they adopt surface acting to receive compliments or to avoid punishments from people they are interacting with such as customers, co-workers, or managers (Sisley & Smollan, 2012). Such motivations are externalized motivations, which are distinctively different from internalized motivations. Prior studies show that extrinsic rewards such as performance-based rewards have positive effects on job satisfaction for service providers adopting surface acting because such extrinsic rewards appear to value emotional labor much more, making such efforts exciting and relevant to service providers (Eisenberger & Aselage, 2009). The effect of extrinsic motivations relating to organizational rewards or social rewards changes depending on which emotional labor strategy—surface acting or deep acting—is utilized. While high levels of extrinsic motivation can elicit a stronger sense of pleasure toward which service providers can work harder, the effect can be more prevalent for those who adopt surface acting than for those who adopt deep acting strategies. As such, high levels of extrinsic motivations for rewards (i.e. organizational rewards or social rewards) attenuate the positive effect of surface acting on burnout because those with surface acting are associated with higher levels of extrinsic motivations. On the other hand, the low level of extrinsic motivation for rewards amplifies the negative effect of deep acting on burnout since the primary motivation for performing their jobs are not related to extrinsic motivations. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

-

H5.

Frontline luxury service providers’ surface acting will be moderated by extrinsic motivations for (a) organizational rewards and (b) social rewards on their burnout.

-

H6.

Frontline luxury service providers’ deep acting will be moderated by extrinsic motivations for (a) organizational rewards and (b) social rewards on their burnout.

Methodology

Data Collection and Sample Characteristics

A web-based online survey was conducted using a nationally recognized consumer research panel service. Three screening questions were asked to recruit qualified survey participants for the study. Only participants who met the following criteria were selected as the final sample: (1) participant is currently working as either a full-time or part-time frontline service provider in the luxury sector, (2) the nature of participant’s daily job requires some level of interaction with customers, and (3) those who have consumed any luxury services within the past 6 months. Those who did not meet our criteria were eliminated from the study sample. A total number of 283 individuals were recruited to participate in the survey. Participants answered the questions to examine the effect of frontline luxury service providers’ emotional labor induced burnout on their dysfunctional behaviors (i.e. customer retaliatory behavior, organizational deviance, and interpersonal deviance). Of the 283 participants, 255 participants (90.1%) work full-time, and 28 participants (9.9%) work part-time in luxury services industry. In terms of sample demographics, males comprised 50.2%, and 49.8% were females. Most participants (81.3%) were in the age group between 19 and 30 years, followed by 15.2% between 31 and 40 years; 44.5% were single, while 55.5% were married. About 39.6% of participants indicated their annual household income before tax as less than $30,000, followed by 30.4% between $30,000 and $60,000, 21.2% between $60,000 and $100,000, and 8.8% more than $100,000. Table 1 presents descriptive statistics (Figs. 1, 2, and 3).

Measures

All measures were adapted to fit our research context from the existing scales. All items used a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, and 7 = strongly agree). The scale items appear in the Appendix. All the survey participants were asked to respond to the survey questions that were used to measure burnout, surface acting, deep acting, organizational deviance, and interpersonal deviance based on their working experience. To measure surface acting and deep acting, we used a scale from Brotheridge and Lee (2003) and Grandey (2003). We adapted a scale from Rutherford et al. (2011) to measure burnout. To measure organizational deviance and interpersonal deviance, we used a scale by Jelinek and Ahearne (2010). The scale for extrinsic motivation for organizational rewards was adapted from a scale by Verleye (2015) and extrinsic motivation for social rewards was adapted from House and Dessler (1974).

To measure customer retaliatory behaviors, a scenario was provided to the participants to see whether the effect of burnout from work can influence another personal domain (i.e. when they become luxury service recipients). The scenario described a condition wherein participants received luxury services that did not meet their service expectations after a long day of work. After the scenario, customer retaliatory behavior was captured by adapting a scale by Grégoire and Fisher (2008). The scenario reads as below:

“After a long day of your work, you went to a store which has a reputation for high-end upscale premium services. However, the quality of the service you experienced did not meet your expectation”

We applied Harman’s single factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003) for common method bias. A principal component analysis of all the items included in the study was performed. No single factor emerged while the first factor accounted for less than 50% of the total variance, falling below the critical threshold. Therefore, we conclude that there is no evidence suggesting the presence of common method bias in this study.

Results

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to evaluate the measurement and structural parameters. The data were analyzed using Amos 22.

Measurement Model Tests

The measurement model was assessed with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using the maximum likelihood estimation. The results of CFA confirmed good fit indices (χ2 = 106.60 with 75 df; GFI = 0.95; NFI = 0.95; CFI = 0.99; IFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.04) of the measurement model. All Cronbach’s alpha values for each variable were above the minimum threshold of .70, suggesting internal consistency in measurement items (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Factor loadings for the indicators for each variable were all significant and sufficiently higher than the recommended value of .50 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). The average variance extracted (AVE) values ranged from .50 to .68, all above .50, confirming convergent validity (Hair et al., 1998). The AVE values were greater than the square of correlation between pairs of constructs, achieving discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Table 2 presents the results of CFA.

Structural Model Tests

After confirming that an adequate fit was obtained for the measurement model, we assessed the structural parameters with the maximum likelihood estimation. The results of goodness of the fit of the structural model showed a good model fit (χ2 = 128.12 with 82 df; GFI = 0.95; NFI = 0.94; CFI = 0.98; IFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.05). Table 3 presents empirical findings of the hypothesized relationships. Frontline luxury service providers’ surface acting had a significant effect on burnout (β = 0.79, p < 0.001, H1). However, luxury service providers’ deep acting had an insignificant effect on burnout (β = 0.07, p = 0.305, H2). In terms of the effect of burnout on workplace deviance behaviors, burnout positively influenced both organizational deviance (β = 0.88, p < 0.001, H3a) and interpersonal deviance (β = 0.95, p < 0.001, H3b). The effect of burnout on customer retaliatory behavior was also found to be positive and significant (β = 0.74, p < 0.001, H4).

Results of Moderation Effects

A multi-group analysis was performed (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988) to examine the moderating effects of extrinsic motivation for organizational rewards and social rewards on the relationships between emotional labor and burnout. The survey respondents were divided into two groups (high vs. low) using a median split: high (n = 141) and low (n = 141) groups of extrinsic motivation for organizational rewards; and high (n = 148) and low (n = 135) groups of extrinsic motivation for social rewards. The result show that the moderating effects of extrinsic motivation for organizational rewards on the relationship between surface acting and burnout (Mlow β = 0.53, p < 0.001; Mhigh β = 0.75, p < 0.001, H5a) and between deep acting and burnout (Mlow β = 0.16, p < 0.001; Mhigh β = −0.10, p < 0.05, H5b) were significantly different between the two group (see Table 4). Additionally, the moderating effect of extrinsic motivation for social rewards on the relationship between surface acting and burnout were significantly different between the two groups (Mlow β = 0.52, p < 0.001; Mhigh β = 0.80, p < 0.001, H6a). However, on the relationship between deep acting and burnout, it was not found out to be different between the two groups (Mlow β = 0.19, p = 0. 072; Mhigh β = −0.13, p = 0.104, H6b) but was significantly different between the high and low groups (see Table 5).

Discussion

The study provides theoretical contributes in four distinct ways: (1) providing a comprehensive theoretical model of antecedents and consequences of burnout: one within the organizational context (i.e. frontline service providers’ work domain) and the other outside of the organizational context (i.e. frontline service providers’ personal domain: when they become service recipients); (2) extending the scope of domains of burnout based on the horizontal spillover theory; (3) emphasizing a special focus on frontline luxury service providers; (4) examining the moderating effects of extrinsic motivations on the relationship between emotional labor strategies (i.e. surface acting and deep acting) and burnout.

First, unlike previous studies that mostly focus on the effect of only burnout within the same domain (i.e. organizational context: e.g. Maslach & Goldberg, 1998), this study contributes to the literature by confirming the negative spillover effects of burnout from two perspectives, that is, within and outside the organizational context. As for the negative spillover effects of burnout within the same domain, our study results confirm the link between burnout and organizational deviance as well as burnout and interpersonal deviance, in line with the existing studies within the organizational context. The essence of such effects is rooted in the fact that burned out employees need to find a way to vent the negative feelings derived from their job. However, in most cases, employees do not have control over their workplace situations. This is more prevalent among frontline service providers as the nature of their jobs involves sustained interpersonal customer interactions with expectations of consistent delivery of excellent service (Dubois et al., 2005; Lee & Ok, 2012; Loureiro & Araujo, 2014; Sherman, 2002). These situations trigger negative feelings such as frustration, lack of autonomy, anger, or anxiety, thereby leading to the frontline service providers accusing the organization itself (i.e. organizational deviance behaviors) and/or co-workers who belong to the organization (i.e. interpersonal deviance) as the cause of such feelings. In short, our study confirms the negative spillover effects of burnout.

Second, this study broadens the scope of the domains that the horizontal spillover effects of burnout can have an impact. According to horizontal spillover theory, the effect of dissatisfaction from the job domain can be carried over to another domain (Sirgy, 2012; Zedeck, 1992). One of the most frequently studied domains is personal life such as home life (Leung, 2011), leisure (Furnham, 1991), and recreational situations (Diener & Larsen, 1984). Yet, the findings from this study prove that horizontal spillover effects of burnout exist in other personal domains: when frontline service providers become service recipients. To the best of our knowledge, this is a new context of the personal domain that has received less attention in the literature. Our findings show that when burned out frontline service providers become service recipients, they could more likely engage in customer retaliatory behaviors after receiving services that are below their expectations. The rationale behind this could be explained from the horizontal spillover effects of burnout, suggesting that burnout leads to customer retaliatory behaviors as service recipients. The finding is noteworthy because our study focuses on the case when internal stakeholders (i.e. frontline service providers) become external stakeholders (i.e. service recipients). Since frontline service providers have a set of high service standards from their own work experience, this transition from frontline service providers to service recipients becomes more interesting to examine. For example, would deep actors expect higher service standards than surface actors in their role as service receivers? This also negates the possibility that frontline service providers who are burned out are more understanding of other frontline service provider’s work conditions and quality of service.

Third, this study confirms the effects of emotional labor strategies on burnout among frontline luxury service providers. Some scholars stated that both surface and deep acting ultimately suppress negative emotions (Gradney, 2003), thereby leading to depletion of emotional resources and workplace burnout (Söderlund, 2017). However, our findings suggest that frontline service providers employing not deep acting but surface acting are likely to experience burnout. This can be explained by the results pertaining to the relationship between emotional labor and burnout in the literature.

Lastly, this study enhances our understanding on the moderation effects of extrinsic motivations on the relationships between emotional labor strategies (i.e. surface acting and deep acting) and burnout. This study shows that the moderating effects of extrinsic motivations for organizational rewards and for social rewards on the relationship between surface acting and burnout were significant but indicated opposite directions as we hypothesized. Specifically, the high level of surface acting is related to higher levels of burnout for frontline service providers who have a high level of extrinsic motivations for organizational and social rewards, compared to counterparts who reported low levels of extrinsic motivations for organizational and social rewards. It is possible that frontline luxury service providers adopting surface acting strategies may feel that they do work for externalized rewards whether they receive actual extrinsic rewards or not. Studies find that extrinsic rewards such as financial incentives have a negative impact on the quantity and quality of motivation (Deci, 1971, 1972; Ryan et al., 1983). Especially, both types of rewards selected for this study – organizational rewards (e.g. financial incentives, direct monetary compensation, and indirect monetary rewards) and social rewards (e.g. supervisory support) – are categorized as external regulation. As external regulation is considered the least autonomous type of extrinsic motivation, this means that service providers are likely to be motivated to get rewards (i.e. extrinsic organizational rewards) or avoid punishment by obtaining supervisory support (i.e. extrinsic social rewards). Simply, the perceived locus of causality tends to be external rather than internal (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Ryan & Deci, 2000a, 2002). Since a high level of extrinsic motivations, particularly the external regulation type, is related to the decreased level of autonomous motivations, those with a high level of extrinsic motivations may experience a severe degree of burnout. Additionally, a high level of extrinsic expectations means that these individuals are more likely to burnout if the actual extrinsic rewards do not meet their extrinsic motivations. The moderating effects of extrinsic motivations for organizational rewards and for social rewards on the relationship between deep acting and burnout were interesting and noteworthy. We found the moderating effects of extrinsic motivations for organizational rewards on the relationship between deep acting and burnout, but we did not find support for the moderating effects of extrinsic motivations for social rewards. Our findings suggest that frontline service providers adopting deep acting strategies were indeed motivated by extrinsic motivations for organizational rewards but not impacted by extrinsic motivations for social rewards. This points to differential effects of extrinsic motivations for organizational rewards versus extrinsic motivations for social rewards for those frontline luxury service providers adopting deep acting.

Managerial Implications

This study provides a few managerial insights regarding the management of frontline luxury service providers. First, managers should understand that it may be inevitable for frontline service providers to experience a high level of burnout due to higher expectations on service delivery in the luxury services sector. Managers must acknowledge the potentially detrimental effect of workplace burnout not only to the organization and but also to the individual employee’s personal life. In order to break this negative feedback loop, companies must recognize and promote the importance of employee well-being. For instance, companies can offer a routine mental and physical health support system as a component of employment benefits. Companies should implement a variety of employee wellness programs such as counseling services, mindfulness practice, meditation, yoga, and emotional labor training embedded in deep acting strategies, thus building a supportive culture of psychological safety. Second, managers should acknowledge that just designing an employee reward system may not guarantee mitigating employees’ burnout. Instead, managers need to understand that managing each service employee’s motivations for rewards can be as important as the actual rewards system. Therefore, they need to periodically examine each employees’ motivations for rewards and confirm if their actual rewards system is designed to fulfill employees’ motivations. Additionally, managers should develop an optimal mix of recognition and rewards systems that can better manage stressful working conditions. Serving high-end customers in luxury service setting come with certain degrees of prestige and recognition through access to premium networks and better social acceptance. Also, more well-designed recognition systems through awards and incentives based on cultivating customer relationships and satisfaction could help in more work value.

Limitations and Future Research

This study has limitations that can be addressed in future research. First, this study adopts Bennett and Robinson (2000)s view on workplace deviance that was classified into two dimensions: organizational deviance and interpersonal deviance. Since this study aims to examine frontline luxury service providers’ workplace deviance behaviors in the organizational context, deviant behaviors toward customers are beyond the scope of this study. Yet, Jelinek and Ahearne (2006) propose an additional dimension-frontline deviance, defined as a voluntary form of employees’ misbehaviors targeting organizational outsiders such as customers. This form of workplace deviance behavior has been studied in different terms such as service sabotage (Harris & Ogbonna, 2006) or retaliation (Madupalli & Poddar, 2014). Since this form of behavior is commonly observed among service settings, as the primary duty of an employee’s job involve customer interactions, future research can adopt three forms of workplace deviance behaviors: intra-organizational deviance behaviors such as organizational and interpersonal deviance and inter-organizational deviance behaviors such as frontline deviance. Second, to measure customer retaliatory behavior, this study used a service failure scenario. Instead of focusing only on the service failure condition, future research can examine if the same findings hold in neutral and success service conditions. Although this study focuses only on extrinsic motivation, particularly the external regulation type, in luxury service industries, it can be assumed that both extrinsic and intrinsic motivations interact differently depending on different levels of emotional labor. Additionally, future research can also examine the moderating effect of all forms of extrinsic motivation along the varying degree of autonomy: external regulation, introjected regulation, identified regulation, and integrated regulation.

References

Ahn, J., Park, J. K., & Hyun, H. (2018). Luxury product to service brand extension and brand equity transfer. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 42, 22–28.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423.

Ashforth, B. E., & Humphrey, R. H. (1993). Emotional labor in service roles: The influence of identity. Academy of Management Review, 18(1), 88–115.

Ashill, N. J., & Rod, M. (2011). Burnout processes in non-clinical health service encounters. Journal of Business Research, 64(10), 1116–1127.

Bakker, A. B., & Heuven, E. (2006). Emotional dissonance, burnout, and in-role performance among nurses and police officers. International Journal of Stress Management, 13(4), 423–440.

Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 349–360.

Berry, C. M., Ones, D. S., & Sackett, P. R. (2007). Interpersonal deviance, organizational deviance, and their common correlates: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 410–424.

Bono, J. E., & Vey, M. A. (2005). Toward understanding emotional management at work: A quantitative review of emotional labor research. In C. E. Härtel, W. J. Zerbe, & N. M. Ashkanasy (Eds.), Emotions in organizational behavior (pp. 224–244). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Brant, A. (2016). The best luxury services are customized, not standardized. Harvard Business Review. Available at: https://hbr.org/2016/03/the-best-luxury-services-are-customized-not-standardized.

Brotheridge, C. M., & Grandey, A. A. (2002). Emotional labor and burnout: Comparing two perspectives of “people work”. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60(1), 17–39.

Brotheridge, C. M., & Lee, R. T. (2003). Development and validation of the emotional labour scale. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 76(3), 365–379.

Chen, K. Y., Chang, C. W., & Wang, C. H. (2019). Frontline employees’ passion and emotional exhaustion: The mediating role of emotional labor strategies. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 76, 163–172.

Chi, N. W., & Grandey, A. A. (2019). Emotional labor predicts service performance depending on activation and inhibition regulatory fit. Journal of Management, 45(2), 673–700.

Cossette, M. (2014). Emotional labor through the lens of self-determination theory. In M. Gagné (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of work engagement, motivation, and self-determination theory (pp. 259–275). New York: Oxford University Press.

Cossette, M., & Hess, U. (2015). Service with style and smile. How and why employees are performing emotional labour? Revue Européenne de Psychologie Appliquée/European Review of Applied Psychology, 65(2), 71–82.

Deci, E. L. (1971). Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 18(1), 105–115.

Deci, E. L. (1972). The effects of contingent and noncontingent rewards and controls on intrinsic motivation. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 8(2), 217–229.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum Press.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Diener, E., & Larsen, R. J. (1984). Temporal stability and cross-situational consistency of affective, behavioral, and cognitive responses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(4), 871–883.

Dubois, B., Czellar, S., & Laurent, G. (2005). Consumer segments based on attitudes toward luxury: Empirical evidence from twenty countries. Marketing Letters, 16(2), 115–128.

Eisenberger, R., & Aselage, J. (2009). Incremental effects of reward on experienced performance pressure: Positive outcomes for intrinsic interest and creativity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(1), 95–117.

Enwereuzor, I. K., Onyishi, I. E., Onyebueke, I. F., Amazue, L. O., & Nwoke, M. B. (2017). Personality as a moderator between emotional exhaustion and workplace deviance among teachers. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 27(1), 41–46.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Fox, S., & Spector, P. E. (1999). A model of work frustration–aggression. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20(6), 915–931.

Furnham, A. (1991). Work and leisure satisfaction. In F. Strack, M. Argyle, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Subjective well-being. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

Gabriel, A. S., & Diefendorff, J. M. (2015). Emotional labor dynamics: A momentary approach. Academy of Management Journal, 58(6), 1804–1825.

Godwyn, M. (2006). Using emotional labor to create and maintain relationships in service interactions. Symbolic Interaction, 29(4), 487–506.

Grandey, A. A. (2000). Emotional regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 95.

Grandey, A. A. (2003). When “the show must go on”: Surface acting and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer-rated service delivery. Academy of Management Journal, 46(1), 86–96.

Grégoire, Y., & Fisher, R. J. (2008). Customer betrayal and retaliation: When your best customers become your worst enemies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(2), 247–261.

Groth, M., Hennig-Thurau, T., & Walsh, G. (2009). Customer reactions to emotional labor: The roles of employee acting strategies and customer detection accuracy. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 958–974.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis. New Jersey: Pearson.

Harris, L. C., & Daunt, K. (2013). Managing customer misbehavior: Challenges and strategies. Journal of Services Marketing, 27(4), 281–293.

Harris, L. C., & Ogbonna, E. (2006). Service sabotage: A study of antecedents and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(4), 543–558.

Harris, L. C., & Ogbonna, E. (2012). Motives for service sabotage: An empirical study of front-line workers. The Service Industries Journal, 32(13), 2027–2046.

Hartline, M. D., & Ferrell, O. C. (1996). The management of customer-contact service employees: An empirical investigation. Journal of marketing, 60(4), 52–70.

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

House, R. J., & Dessler, G. (1974). The path-goal theory of leadership: Some post hoc and a priori tests. In J. G. Hunt & L. L. Larson (Eds.), Contingency approaches to leadership. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Hülsheger, U. R., & Schewe, A. F. (2011). On the costs and benefits of emotional labor: A meta-analysis of three decades of research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(3), 361–389.

Jelinek, R., & Ahearne, M. (2006). The enemy within: Examining salesperson deviance and its determinants. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 26(4), 327–344.

Jelinek, R., & Ahearne, M. (2010). Be careful what you look for: The effect of trait competitiveness and long hours on salesperson deviance and whether meaningfulness of work matters. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 18(4), 303–321.

Johansson, M., & Naslund, L. (2009). Welcome to paradise. Customer experience design and emotional labour on a cruise ship. International Journal of Work Organisation and Emotion, 3(1), 40–55.

Johnson, H. A. M., & Spector, P. E. (2007). Service with a smile: Do emotional intelligence, gender, and autonomy moderate the emotional labor process?. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12(4), 319.

Kim, T., Yoo, J.-E., Lee, G., & Kim, J. (2012). Emotional intelligence and emotional labor acting strategies among frontline hotel employees. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 24(7), 1029–1046.

Lee, J. J., & Ok, C. M. (2012). Reducing burnout and enhancing job satisfaction: Critical role of hotel employees’ emotional intelligence and emotional labor. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(4), 1101–1112.

Lee, J., Ok, C. M., Lee, S. H., & Lee, C. K. (2018). Relationship between emotional labor and customer orientation among airline service employees: Mediating role of depersonalization. Journal of Travel Research, 57(3), 324–341.

Leung, L. (2011). Effects of ICT connectedness, permeability, flexibility, and negative spillovers on burnout and job and family satisfaction. Human Technology: An Interdisciplinary Journal on Humans in ICT Environments, 7(3), 250–267.

Loureiro, S. M. C., & de Araújo, C. M. B. (2014). Luxury values and experience as drivers for consumers to recommend and pay more. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 21(3), 394–400.

Lunardo, R., & Mouangue, E. (2019). Getting over discomfort in luxury brand stores: How pop-up stores affect perceptions of luxury, embarrassment, and store evaluations. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 49, 77–85.

Madupalli, R. K., & Poddar, A. (2014). Problematic customers and customer service employee retaliation. Journal of Services Marketing, 28(3), 244–255.

Magnini, V. P., Baker, M., & Karande, K. (2013). The frontline provider’s appearance: A driver of guest perceptions. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 54(4), 396–405.

Malik, M. S., Sattar, S., Younas, S., & Nawaz, M. K. (2019). The workplace deviance perspective of employee responses to workplace bullying: The moderating effect of toxic leadership and mediating effect of emotional exhaustion. Review of Integrative Business and Economics Research, 8(1), 33–50.

Maslach, C., & Goldberg, J. (1998). Prevention of burnout: New perspectives. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 7(1), 63–74.

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Burnout. In G. Fink (Ed.), Stress: Concepts, cognition, emotion, and behavior. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422.

Mottaz, C. J. (1985). The relative importance of intrinsic and extrinsic rewards as determinants of work satisfaction. The Sociological Quarterly, 26(3), 365–385.

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychological theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Phillips, B., Tan, T. T. W., & Julian, C. (2006). The theoretical underpinnings of emotional dissonance: A framework and analysis of propositions. Journal of Services Marketing, 20(7), 471–478.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Prentice, C. (2016). Leveraging employee emotional intelligence in casino profitability. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 33, 127–134.

Qin, S., Young, C. B., Supekar, K., Uddin, L. Q., & Menon, V. (2012). Immature integration and segregation of emotion-related brain circuitry in young children. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(20), 7941–7946.

Quach, S., Jebarajakirthy, C., & Thaichon, P. (2017). Aesthetic labor and visible diversity: The role in retailing service encounters. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 38, 34–43.

Robinson, S. L., & Bennett, R. J. (1995). A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: A multidimensional scaling study. Academy of Management Journal, 38(2), 555–572.

Rubin, R. S., Tardino, V. M. S., Daus, C. S., & Munz, D. C. (2005). A reconceptualization of the emotional labor construct: On the development of an integrated theory of perceived emotional dissonance and emotional labor. In C. E. Härtel, W. J. Zerbe, & N. M. Ashkanasy (Eds.), Emotions in organizational behavior (pp. 201–223). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Rutherford, B. N., Hamwi, G. A., Friend, S. B., & Hartmann, N. N. (2011). Measuring salesperson burnout: A reduced Maslach burnout inventory for sales researchers. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 31(4), 429–440.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000a). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54–67.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000b). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic dialectical perspective. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 3–33). New York: The University of Rochester Press.

Ryan, R. M., Mims, V., & Koestner, R. (1983). Relation of reward contingency and interpersonal context to intrinsic motivation: A review and test using cognitive evaluation theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(4), 736–750.

Sherman, R. (2002). Better than your mother: Caring labor in luxury hotels. Berkeley Collection of Working and Occasional Papers.

Sherman, R. (2005). Producing the superior self: Strategic comparison and symbolic boundaries among luxury hotel workers. Ethnography, 6(2), 131–158.

Sherman, R. (2007). Class acts: Service and inequality in luxury hotels. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sirgy, M. J. (2012). The psychology of quality of life: Hedonic well-being, life satisfaction, and eudaimonia. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Science & Business Media.

Sisley, R., & Smollan, R. (2012). Emotional labour and self-determination theory: A continuum of extrinsic and intrinsic causes of emotional expression and control. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 37(2), 41–57.

Söderlund, M. (2017). Employee display of burnout in the service encounter and its impact on customer satisfaction. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 37, 168–176.

Som, A., & Blanckaert, C. (2015). The road to luxury. New York: Wiley.

Totterdell, P., & Holman, D. (2003). Emotion regulation in customer service roles: Testing a model of emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 8(1), 55–73.

Tracy, S. J. (2000). Becoming a character for commerce: Emotion labor, self-subordination, and discursive construction of identity in a total institution. Management Communication Quarterly, 14(1), 90–128.

Verleye, K. (2015). The co-creation experience from the customer perspective: Its measurement and determinants. Journal of Service Management, 26(2), 321–342.

Weiss, N. H., Forkus, S. R., Contractor, A. A., & Schick, M. R. (2018). Difficulties regulating positive emotions and alcohol and drug misuse: A path analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 84, 45–52.

Zapf, D., Seifert, C., Schmutte, B., Mertini, H., & Holz, M. (2001). Emotion work and job stressors and their effects on burnout. Psychology & Health, 16(5), 527–545.

Zedeck, S. (1992). Introduction: Exploring the domain of work and family concerns. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), Work, families, and organizations (pp. 1–32). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Declarations

This paper received IRB approval. All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution or practice at which the studies were conducted. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection and analysis were performed by Hyowon Hyun. The first draft of the manuscript was written by all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

* The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Construct | Measurement item with indicator |

|---|---|

SA1. I put on an act in order to deal with customers in an appropriate way | |

SA2. I resist expressing my true feelings | |

SA3. I pretend to have emotions that I do not really have | |

DA1. I do work hard to feel the emotions that I need to show to others. | |

DA2. I make an effort to actually feel the emotions that I need to display to others | |

DA3. I really try to feel the emotions I have to show as part of my job | |

Burnout Rutherford et al. (2011) | BO1. I feel used up at the end of the workday |

BO2. I feel burned out from my work | |

Organizational deviance Jelinek and Ahearne (2010) | OD1. I put off work-related duties to attend to personal |

OD2. I used company resources (paper, suppliers, fax, copier) for personal purposes | |

Interpersonal deviance Jelinek and Ahearne (2010) | ID1. I accepted credit for the work of other people |

ID2. I criticized coworkers and colleagues | |

ID3. I blamed coworkers and colleagues when things went wrong at work | |

Customer retaliatory behavior Grégoire and Fisher (2008) | CRB1. When I receive a service in the situation above, I would complain to the store to make someone from the service pay for its poor service |

CRB2. When I receive a service in the situation above,a I would complain to the consumer agency so that it could spread the word about my misadventure | |

Extrinsic motivation for organizational rewards Verleye (2015) | EMOR1. When I suffer from emotional labor from my job, an appropriate financial incentive can make me feel better |

EMOR2. When I suffer from emotional labor from my job, direct monetary compensation (e.g., one-time bonus, pay raise) can make me feel better | |

EMOR3. When I suffer from emotional labor from my job, indirect monetary rewards (e.g., promotional opportunities, benefits package) can make me feel better | |

Extrinsic motivation for social rewards House and Dessler (1974) | EMSR1. When I suffer from emotional labor from my job, I can approach my supervisor |

EMSR2. When I suffer from emotional labor from my job, I seek help from my supervisor to make the job more pleasant | |

EMSR3. In a job involving high emotional labor, my supervisor supports all workers by treating them as his/her equal |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hyun, H., Lee, K.K., Chung, JH. et al. When service providers become service recipients: negative spillover effects of burnout among luxury service providers. Curr Psychol 42, 1270–1283 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01502-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01502-3