Abstract

Based on the conservation of resources theory, this study developed a model linking social undermining to employees helping behaviors and work role performance via expression of guilt, with religious faith possessed by employees as a first-stage moderator. We argue that individuals will feel guilty if they perceive themselves as the perpetrators of the social undermining against their coworkers. Feeling guilt can potentially trigger prosocial responses (i.e., helping coworkers) and enhance work role performance for improving the situation. We contend that religious faith that commands doing good with others further provides resources for managing these negative emotions to unleash a positive side of social undermining, such that the relation of social undermining with an expression of guilt will be strengthened. A multisource (supervisor-supervisee), multi-wave, and multi-context (education, healthcare, and banking) survey involving 281 employees largely supports our study hypotheses. The results indicated that social undermining is associated with more guilt expressions amid religious individuals, revealing higher prosocial and work role performance. For business ethics research, the current study unveils an important mediator—guilt expressions about wrongdoing—via which individuals’ social undermining behaviors at work, somewhat counterintuitively, lead to boost performance outcomes, and an employee’s religious faith helps a facilitator of this relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent business scholarship reveals that adverse and resource-depleting situations remain a significant concern for organizations because the consequences that arise from such situations can hinder the performance of the individual employee and that of the whole organization (Park et al., 2018; Probst et al., 2020). For example, the intentional attempt of an employee to socially undermine (Mostafa et al., 2020) their coworkers in terms of their ability to maintain positive relationships, accomplish work-related success and destroy their favorable reputations can have a severe problem for both perpetrator and target. Unfortunately, while studying social undermining, relatively less devotion has been made to how perpetrators react to their social undermining behaviors (Eissa et al., 2020). Specifically, investigating the outcomes of such social undermining behaviors in terms of perpetrators is rare.

Social undermining, by definition, has negative connotations and thus has adverse effects, but might it have some positive consequences? For example, the perpetrator of socially undermining behaviors can recognize it as inappropriate and thus may try to correct it. We argue that employees with religious faith (Eaves et al., 2008) while practicing social undermining, might particularly feel bad, which in turn boosts their expression of a sense of guilt (Julle-Danière et al., 2020). The expression of guilt can play an imperative role in molding the workplace behaviors of the perpetrators (Julle-Danière et al., 2020) like they can express helping behaviors and improve their work role performance (Yue et al., 2017). Investigating these positive outcomes, we add to the business ethics literature by arguing that organizations can lose something valuable while ignoring the importance of interpersonal work behaviors.

We employed the conservation of resource (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 2001; Hobfoll et al., 2018) to elucidate the relationships between study variables. According to this theory, an employee, while confronting resource depletion, whether caused by him or someone else, tries to overcome such depletion by involving in appropriate responses or undoing the resource depletion (Hobfoll & Shirom, 2000). The extent of responsiveness is great when the personal characteristics of people are more affected by the resource depletion experienced (Hobfoll, 2001; Hobfoll & Shirom, 2000). Furthermore, this theory asserts that employees get more energy from such responses to exhibit behaviors that overcome resource depletion to gain extra resources. Drawing on COR, we postulate that the employees with religious faith, when they socially undermine a coworker, may suffer from demeaning self-esteem —— a valuable resource that employees firmly seek to protect, for which they can realize and acknowledge the negative consequences of their actions (Hobfoll, 1989, 2001). The sense of realizing and acknowledging the negative implications of their actions as informed by their religious faith can push them to exhibit helping behaviors and improve their work role performance.

Although preaching any religious belief system is considered illegal and unacceptable in most countries, they tend to be neutral in this regard; however, religious beliefs cannot be undermined in organizational behavior research (Weaver & Agle, 2002). Extant research accumulated on how the religious faith of employees can lead to various positive attitudes and behaviors such as organizational commitment (Farrukh et al., 2016), job satisfaction (Kutcher et al., 2010), emotional attachment to the organization (Sikorska-Simmons, 2005), and organizational citizenship behavior (Kutcher et al., 2010). In addition, the religious faith used as a buffering variable can help employees to reduce the severity of difficult work conditions such as work-family conflict (Dar & Rahman, 2020; Pandey & Singh, 2019), abusive supervision (Arshad et al., 2019), organizational stress, and burnout (Jamal & Badawi, 1993) and prevent them from expressing negative outcomes. While relying on this research foundation, we argue that the religious faith of employees as a personal resource can help them express positive behaviors in the presence of social undermining.

This positive role of religious faith can be observed extensively in those countries where the religious belief system is affecting the common and organizational life of people. For example, in Pakistan, where most people are Muslims and thus strongly believe in God, they firmly influence their workplace behaviors (Dar & Rahman, 2020; Zaman et al., 2018). In this view, investigating the impacts of religious faith on harmful behaviors such as social undermining is imperative, especially at a time of increasing trading interactions among Muslims and the Western World (Daly et al., 2017). In addition, it can also play a prominent role in increasing levels of religious diversity in working teams around the globe (Berry et al., 2011). Therefore, it is a prerequisite for most organizations to understand how the personal characteristics of their workforce, as informed by their religious faith, can mitigate the harmful consequences of their unwelcome behaviors.

In summary, this study contributes to business ethics research by molding the prevalent focus on antecedents of social undermining to its outcomes. Applying the notion of COR (Hobfoll, 2001), we argue that employee high on religious faith feels more guilty for any damage they have done to others by exhibiting socially undermining behavior at the workplace. This expression of guilt can motivate employees to express behaviors in enhancing organizational well-being, that is, to fulfill assigned tasks efficiently and show helping behaviors (Yue et al., 2017). We accordingly add to business ethics research by exhibiting how organizations can address a negative situation (social undermining) by transforming it into favorable outcomes (helping behaviors and enhanced work role performance), particularly among individuals with high levels of religious faith, which lead them to feel guilty for the damage they have made on other due to social undermining.

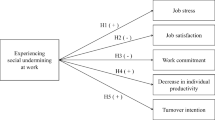

The relationships among study variables are presented in Fig. 1, where the social undermining leads to the expression of guilt which can lead to expressing helping behavior and enhanced work role performance. Further, the religious faith strengthens this beneficial process by giving a sense of correcting the wrongdoing.

Hypotheses Development

Social Undermining, Expressions of Guilt, and Religious Faith

According to COR (Hobfoll & Shirom, 2000) perspective, when employees experience resource depletion, they try to reduce or undo it. Further, this theory asserts that employees tend to protect their existing resources when unpleasant experiences occur in the workplace (Hobfoll & Shirom, 2000). When socially undermining their coworkers, employees think of themselves as unworthy, and they feel that they are not concerned for others, which hinders their self-image (Eissa et al., 2020; Pierce & Gardner, 2004). These psychological thoughts, like feeling guilty, compel them to express these feelings in interpersonal relationships, which assist them in protecting their self-worth (Hobfoll et al., 2018; Ilies et al., 2013). Due to the expression of guilt and acknowledging their wrong actions, the employees expressing social undermining might believe that they have mitigated the consequences of wrongdoing to others, which helps them to restore their self-esteem or self-worth (Bowling et al., 2010; Liu & Xiang, 2018). The expression of guilt plays the role of a coping strategy that helps employees protect themselves from devaluation (Burmeister et al., 2019).

Social undermining by having negative connotations can have positive consequences contingent upon people’s characteristics. According to COR theory, how employees respond to a resource drainage experience depends on their personal beliefs about the severity of the resource drainage experience (De Clercq & Bouckenooghe, 2019). Research has shown that religious people believe in doing well with others and not inflicting harm because their religious principles demand doing so. This conviction might inform people high on religious faith about their social undermining behaviors with the feeling guilty of doing wrong to others (Haq et al., 2020) and violating their belief system and spiritual principles. This sense of feeling guilty in response to social undermining behaviors can trigger religious people to do good which facilitates them to preserve their self-esteem resources (Hobfoll, 2001). In light of this reasoning, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1

There is a positive relationship between employees’ social undermining and their expressions of guilt triggered by their religious faith.

The expression of guilt enables people to express some positive behaviors to get personal satisfaction. After acknowledging and accepting their wrongdoing, people have high intentions to do something good (Burmeister et al., 2019). Applying the COR theory, employees with such positive intentions can get additional resources (Hobfoll & Shirom, 2000). Thus being apologized for their wrongdoing to other employees is more likely to be personally satisfied by expressing positive behaviors that benefit the target or the employer (Hareli et al., 2005; Hobfoll et al., 2018). Involvement in positive behaviors such as helping other coworkers and improving the work role performance can emerge due to this acknowledgment of wrongdoing with others. Such behaviors justify their wrongdoing and can enhance their sense of personal fulfillment (Ilies et al., 2013). It means that the expression of guilt can lead to positive outcomes like expressing helping behaviors and enhancing work role performance. Doing so enables employees to gain personal resources like personal satisfaction and a sense of personal fulfillment. Thus, it is hypothesized:

Hypothesis 2

There is a positive relationship between employees’ expressions of guilt and their (a) helping behaviors and (b) work role performance.

The above reasoning recommends a moderated-mediation mechanism (Hayes & Rockwood, 2020), where the religious faith (Eaves et al., 2008) buffers the indirect relationship between social undermining and helping behaviors and enhances work role performance through the expression of guilt (Julle-Danière et al., 2020). The religious belief system of employees that commands doing good to others and making up the past wrongdoing with others helps them protect their self-esteem and self-worth (Hareli et al., 2005; Hobfoll et al., 2018). Their expression of guilt and acknowledgment of the wrongdoing work as a coping strategy that enables them to express helping behaviors and enhance work role performance to gain additional resources of self-worth and personal fulfillment (Ilies et al., 2013). This argument explains how social undermining can result in helping behaviors and enhance work role performance. Thus, we hypothesized:

Hypothesis 3

There is an indirect positive relationship between employees’ social undermining and their (a) helping behavior and (b) work role performance through their expressions of guilt, as triggered by their religious faith.

Research Method

Research Context, Sample, and Procedures

The research hypotheses were tested with survey data collected among Pakistani-based employees working in 12 firms in various sectors, including educational institutions, financial institutions, and healthcare organizations. Drawing a sample from multiple functional groups helps enhance the research findings’ external validity (Highhouse, 2009). Moreover, the arguments that underpin the study hypotheses should apply across various countries. Interestingly, data based on Pakistan offered an attractive setting because of the critical role of spirituality in the country (Haq et al., 2020) and its pertinent cultural features. For instance, Pakistan stood high in uncertainty avoidance score (Hofstede et al., 2005), which proposes that when individuals understand they have hurt others or possess a fear of vengeful acts, they experience extreme stress.

Consequently, employees may seek to address the issue by involving in positive work-related behaviors. Likewise, Hofstede et al. (2005) suggest that Pakistan’s emphasis on group harmony increases the likelihood that individuals seek to accept their misconduct and contribute more to the organizational collective with their committed work efforts. Accordingly, studying how individuals react to their social undermining with compensating behaviors and the likely enabling role of their religious faith is extremely relevant in this country’s context.

A convenience sampling approach was utilized for data collection. Two of the authors have personal contacts in these organizations. Initially, official approval from higher authorities was obtained after briefing them regarding the study objectives. Then, to double-check the accuracy and validity of the study questionnaires, we invited two professors in the field of organizational behavior who teach at universities to help revise the scale. Both professors have many years of teaching and research experience in OB, have research publication records in high-quality journals, and are currently working on different research projects. After carefully reading, the two experts agreed on the content of the questionnaire to a more considerable extent. However, they had a few suggestions that the authors had incorporated before disseminating the survey among the participants. For example, one item of social undermining is “How often has your supervisor intentionally insulted you.” Replaced by “How often have you intentionally insulted your coworker?” Similarly, one item of religious faith is “I feel like I can always count on God.” Replaced by “I feel like I can always count on Allah/God.” (See Appendix A). Afterward, individual participants were contacted via their organizations’ internal mailing systems. To ensure respondents’ rights and confidentiality, we took several steps in this process. Specifically, we use an online electronic questionnaire for data collection. This way of data collection helps to guarantee the respondent’s anonymity (Lim, 2002). Further, a letter was dispatched along with a questionnaire to assure participants that only research team members, not their organizations, would have access to their responses. In addition, we underlined that there were no right or wrong answers and that they could withdraw from the research at any point in time.

The data were collected in three wave design, with a two-week lag in-between each round to grant temporal segregation between the data collection for the independent, moderator (phase 1), and mediator (phase 2) variables. To minimize the chances of common method bias (CMB) and to make sure that respondents can less likely predict the overall study model (Podsakoff et al., 2003), in the third phase, we asked the immediate supervisors to assess his/her subordinate’s extra-role (i.e., helping behaviors) and work-role performances. Of the 475 administered surveys, 367 were returned in the first wave. However, out of 367, we removed 15 responses as they failed to answer one of the three attention check questions. Attention check questions are used to exclude inattentive respondents (Thompson et al., 2020). Of these, 346 responded in the second wave and 302 in the third wave. However, we omitted 12 and 13 participants who failed the attention check questions in the second and third waves, respectively.

Further, eight more responses were eliminated due to a lack of required information. Therefore, after excluding surveys with incomplete data, we retained 281 questionnaires for the study analysis, reflecting a response rate of 59%. In the final sample set, most respondents (67%) were male, 85% had a university degree, and their organizations had employed 86% of respondents for more than one year.

The researchers took numerous steps to overcome the potential common method bias (CMB). Firstly, the authors temporally segregated the data collection period by 2 weeks for the study variables (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Secondly, this research employed an online survey. Lim (2002) argued that online survey has the advantage of ensuring that social desirability is kept to a minimum. Thirdly, the current study includes interaction and mediation effects. Harrison et al. (1996) suggest that the respondents are less likely to know the basic theory that may systematically bias their responses in such studies. Hence, CMB is less likely in our study. CMB will be discussed in the results section in detail.

Measures

Coworker Social Undermining

We assessed coworker social undermining by employing a 13-item scale adapted from (Duffy et al., 2002). The study respondents were asked to rate how repeatedly their coworkers had been involved in a number of behaviors. Two sample items include “Hurt your feelings” and “Did not give as much help as they promised.”

Expression of Guilt

We measured the degree to which individuals showed they felt terrible about their earlier actions using a five-item scale of guilt, a component of the Spanish Burnout Inventory (Gil-Monte & Faúndez, 2011). Two sample items were, “In my conversations with coworkers, I express regrets about some of my bad behaviors at work,” and “In my conversations with coworkers, I express how I feel bad about some of the things I have said at work.”

Religious Faith

We assessed the degree to which employees possess firm religious beliefs with a 16-item religious faith scale (Eaves et al., 2008). Two sample items were, “My faith in Allah/God shapes how I think and act every day,” and “I ask Allah/ God to help me make important decisions.”

Helping Behaviors

Helping behavior was defined as voluntary behavior of individuals conducted to assist coworkers in solving work problems. To assess supervisor-rated individuals helping behaviors, we used a five-item scale adapted from the study of Tang et al. (2008). The authors made it clear in the items that the recipient of help is one’s colleagues. The two sample items of the scale include “This employee helps coworkers who have heavy workloads” and “This employee helps coworkers who have been absent.”

Work Role Performance

We measured the supervisor-rated employees’ work role performance using a 9-items scale obtained from (Griffin et al., 2007). This scale consists of three dimensions, i.e., individual task proficiency, individual task adaptivity, and individual task proactivity. Three sample items were, “I carried out the core parts of my job well,” “I adapted well to changes in my core tasks,” and “I initiated better ways of doing my core tasks.”

Results

Measurement Tests and Assessment of the Common Method

We used AMOS (20.0) to confirm the fitness of the measurement model wherein we connected the variables’ items to their corresponding variables getting a multi-dimensional model. The outcomes of the measurement model reveal that the model substantially fulfills the criteria for the fitness indices suggested by Hu and Bentler (1999) and J. F. ). Thus the hypothesized five-factor model (coworker social undermining, expression of guilt, religious faith, helping behaviors, work role performance) fit the data well (χ2/df = 1.925, CFI = 0.958, RMSEA = 0.057, SRMR = 0.048, and p < 0.01).

To ensure the instrument validity (discriminant and convergent validity) and reliability, we have followed the guidelines of J. F. ) and Fornell and Larcker (1981), wherein we have employed the Cronbach’s alpha (CA), composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE) and factor loadings. Table 1 presents the factor loadings (0.654 to 0.936), CA (0.924 to 0.967), CR (0.924 to 0.966), and AVE (0.588 to 0.730) for all constructs that are all above the cut-off criteria for validity and reliability and are all in the acceptable range, as suggested by Hu and Bentler (1999).

Moreover, by comparing the values of AVEs’ square roots and of the inter-correlations of all variables, it was found that the AVEs’ square roots are higher than the inter-correlations, thus revealing a robust discriminant validity for scales (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Thus, these statistics confirm the robustness of the reliability and validity of all study measures, thus allowing us to conduct the relationship-based analysis confidently. Furthermore, Table 2 presents descriptive statistics and inter-correlations among the study variables, and the results suggest that all the relationships are in the expected directions.

Furthermore, we conducted three remedies to test the common method bias: Harman’s single-factor test, controlling for the effects of a single unmeasured latent method factor, and CFA marker variable technique (Podsakoff et al., 2003). First, the measures of five variables, coworker social undermining, expression of guilt, religious faith, helping behaviors, and work role performance, were subjected to exploratory factor analysis (principal components) with oblique rotation. The five factors collectively account for 68.713% of the total variance. The first factor explained 29.807% of the variance, which is less than the 50% benchmark used in Harman’s single factor test, suggesting that common method variance was not present in the data. Second, a single common method factor approach was used. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted. All items of the five scales were loaded on their respective factors (the five factors), and all those items were loaded on one created common method factor with loadings forced to be equivalent. The fit indices of this model were good (χ2 (1065) = 2254.943, IFI = 0.902, CFI = 0.901; RMSEA = 0.063), but they were poorer than those fit indices of the hypothesized measurement model (χ2 (1066) = 2186.695, IFI = 0.907, CFI = 0.907; RMSEA = 0.061). The results showed that the addition of a common method factor did not improve model fit. Third, to examine the potential influence of common method variance in our data, we applied the CFA marker variable technique by Williams, Hartman, and Cavazotte (2010). In line with the recommendations of Williams et al. (2010) and Kovjanic et al. (2012), we selected coworker social undermining as a marker variable because it has the weakest relationship to other variables in the model (Table 2). The first step was to create a baseline model (Model 1) based on CFA. In Model 1, we fixed the marker variable’ parameters to the values obtained from the initial CFA model and forced to zero the correlations between the marker variable and all four variables. In the second model (Method-U model), all other items were loaded on the marker variable factor (coworker social undermining). The final model (Method-R model) is identical to the Method-U model, but the correlations between the variables are constrained to their values from the baseline model. The results showed that the Method-R model was not superior to the Method-U model (Δχ2 [6] = 3.279, p = 0.77). In general, CMB did not represent a grave threat to the validity of research findings.

Structural Equation Modeling and Hypotheses Testing

The fitted and acceptable measurement model was converted to a path model to check the fitness of the path model. The results confirm that the path model successfully achieved the criteria of model fitness indices (χ2/df = 1.997, CFI = 0.912, RMSEA = 0.060, and p < 0.01), as suggested by Hu and Bentler (1999) and J. ). To confirm the proposed relationships (see Fig. 2), we then calculated standardized path coefficients employing the maximum likelihood method in AMOS. Results confirmed the positive effect of coworker social undermining on the expression of guilt (β = 0.224, p < 0.01), and Fig. 3 further provides support for the influence of coworker social undermining on the expression of guilt as the relationship is stronger at a higher level of religious faith (vs. low), hence H1 is supported. Next, Fig. 2 also indicates that expression of guilt positively influences helping behaviors (β = 0.351, p < 0.01) and work role performance (β = 0.260, p < 0.01), hence H2a and H2b also supported.

To test the moderated mediation effect, postulated in Hypotheses 3a–3b (see Table 3), we applied the well-established bootstrapping method (Preacher et al., 2007) through Process macro (Hayes, 2015). This method generated confidence intervals (CI) for the conditional indirect effects of coworker social undermining on helping behavior and work role performance at different levels of the moderator, thereby alleviating concerns about statistical power if these effects were not to follow a normal distribution (MacKinnon et al., 2004). The results indicated stronger indirect effect sizes at increasing levels of religious faith (Table 3). For helping behaviors, the effect sizes went from 0.018 at one SD below the mean of the moderator, to 0.069 at its mean, to 0.119 at one SD above its mean. For work role performance, these values equaled 0.013, 0.048, and 0.084, respectively. As a direct test for the presence of moderated mediation, we assessed the indices of moderated mediation and their associated CI (Hayes, 2015). For helping behaviors, this index equaled 0.037; for work role performance, it equaled 0.026. In both cases, the CI of the indices did not include 0 ([0.010; 0.070] and [0.008; 0.053], respectively). These results affirmed that employees’ religious faith triggered the translation of coworker social undermining into enhanced helping behaviors and work role performance, consistent with Hypotheses 3a–3b and the study’s overall theoretical framework.

Discussion

Social underpinning due to having negative connotations is regarded as a predictor of negative outcomes, whereas can it has some positive outcomes is a question that needs an answer. To fill this important gap in the business ethics literature, we do this research to explore the relationship between social undermining and employees’ work outcomes, employing expression of guilt as a mediator and religious faith as a boundary condition of this relationship. More specifically, applying the COR theory (Hobfoll et al., 2018) this research proposed that (1) while exhibiting social undermining, the religious employees express a feeling of guilt as a key response (2) such as guilt expressions from employees enable their extra roles (i.e., helping coworkers) and work-role performances. Our findings reveal that social undermining had a positive association with the expression of guilt due to the high levels of religious faith. Additionally, the expression of guilt has a positive relationship with both helping behaviors and work role performance. Furthermore, results also support the conditional moderating effect of religious faith on the relationship between social undermining and helping behaviors and work role performance via expression of guilt. Our research findings fully support the hypothesized model (Fig. 1) and offer implications for theory and practice.

Theoretical Implications

The findings of this research have several theoretical implications. First, drawing upon COR theory (Hobfoll et al., 2018), we provide a novel explanation of why the expression of guilt and religious faith elucidate the relationship between social undermining and both helping behaviors and work role performance. Moreover, social undermining due to having negative connotations has always been studied with negative outcomes (Greenbaum et al., 2012). Therefore, linking social undermining with helping behaviors and work role performance is a noticeable contribution to our study.

Second, we found expression of guilt as a critical mediating variable in the relation of social undermining and both helping behaviors and work role performance. Drawing on COR theory (Hobfoll et al., 2018), an employee, while inflicting harm on others (social undermining), may feel guilty (expression of guilt) due to diminished self-esteem- a critical personal resource, which in turn can stimulate positive behaviors such as helping coworkers and enhance work role performance, to gain the resources such as high self-esteem. In general, applying COR theory, we provide a new and comprehensive insight to understand the underlying mechanisms of the impact of social undermining behaviors on positive outcomes such as helping behaviors and work role performance.

Third, this research takes religious faith as an important contingent factor that can reduce the intensity of social undermining in terms of negative outcomes such as decreasing both helping behaviors and work role performance through the expression of guilt. The employees high on religious faith when inflicting harm on others, such as social undermining, feel guilty because of violating the principles of their religious faith, which create a situation of self-depreciating thoughts (Liu & Xiang, 2018). Employees high on religious faith believe that their behavior and personal belief should be consistent. Due to this situation, they seek to undo their wrongdoing and thus, in turn, are more likely to exhibit positive behaviors like helping behaviors and work-role performance considering them highly fulfilling. Employees high on personal religiosity due to enforcement of their religious standards show more ethical practices such as helping behavior (Hansen et al., 1995; Kirchmaier et al., 2018). This study does not claim that employees with a high level of religiosity will only feel bad for their wrongdoing rather than other personal characteristics like empathy (Clark et al., 2019) and adaptability (Pulakos et al., 2000) play an imperative role in this regard.

In summary, this research contributes that the expression of guilt minimizes the negative consequences of social undermining in employees high on religious faith and obliges them to enhance their job performance (helping behavior and work role performance). The study also adds to the literature on religiosity, where it has a direct relationship with positive outcomes such as organizational citizenship behavior (Kutcher et al., 2010), and employee commitment (Mathew et al., 2018). Furthermore, this research highlights the critical role of religious faith in mitigating harmful behaviors such as social undermining.

Practical Implications

The current study’s findings offer several implications for organizational managers. First, social undermining may also have reasons like challenge stressors (e.g., time constraints, work overload, and work incivility) (Meier & Cho, 2019). During such fraught situations, organizations need to boost the level of the personal beliefs of their employees, which will help them to manage their wrongdoing better. This study has taken the religious faith as a unique resource that is tested empirically and evidenced that it can play an important role in fraught situations and mold employees’ social undermining behaviors into enhancing job performance due to expression of guilt for their inflicted wrongdoing.

Second, we do not claim that only those who believe in God will feel guilty for the harm they inflict on others and that it should be the criteria for recruitment and selection. Based on our findings generally, we can claim that employees, who have personal values that are attributed with high care and empathy towards others, can compel employees to repent the negative behaviors toward others with positive behaviors because due to such personal values, they realize the harm they have done to others. Therefore, the organization should encourage its employees to hold and embrace such personal values. For this purpose, organizations should integrate such materials into employee orientation programs to help them maintain positive personal resources. They should also onboard their new employees on the negative consequences of deviant behaviors, such as social undermining, to be managed before it takes place.

Third, this study also offers an important insight that when an employee suffers from self-depreciating thoughts by exhibiting social undermining behaviors, where they feel diminished self-esteem, the religious faith supports them in getting back the self-esteem lost by expressing guilt of inflicting harm on others and in response show positive behaviors such as helping coworkers. The expression of guilt plays an imperative role in shaping the intentions of those inflicting harm on others. Therefore the organization and managers should also encourage fostering personal values other than a religious faith which feel employees the expression of guilt. The expression of guilt will motivate employees to show positive behaviors such as helping behaviors and work role performance to restore their diminished self-esteem due to inflicting harm on others.

Finally, the study’s findings do not inform organizational managers that social undermining is good and will always have positive consequences. Instead, the findings reveals how deviant behaviors such as social undermining can be better managed. The organization managers should try to discourage the practice of harmful behaviors; however, if it happens, they should enrich the organizational environment with resources that assist in mitigating the negative consequences of these harmful behaviors. They should have a mechanism that directly reports the grievances against those involved in such behaviors and publicizes such behaviors’ consequences. Due to this mechanism, those who intend to commit socially undermining behaviors will avoid such occurrences because they fear publicly diminished self-esteem.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

This study has some potential limitations that could be handled in other studies in the future. First, this study has a methodological limitation. We employed a cross-sectional design. Although the theory used suggests that social undermining leads to both helping behaviors and work role performance via expression of guilt, we cannot draw a definitive conclusion about the causal relationship between all the study variables. Future research could adopt a longitudinal design to replicate our research to address this limitation.

Second, although the COR theory is a new perspective used in this study to explain how social undermining leads to helping behaviors and work role performance through the expression of guilt, other theoretical perspectives may also be used to understand the underlying mechanism. In this study, it is found that expression of guilt mediates between social undermining and both helping behaviors and work role performance; thus, we hope future research using other theoretical perspectives (i.e., diminished self-esteem, desire for revenge) may further explain the mediation processes of social undermining.

Third, this study has only considered the religious faith as a personal support resource that can play an imperative role while treating self-depreciating situations. This research explained how individuals at different levels of religious faith, after inflicting harm (i.e., social undermining) on others, respond in more positive behaviors (i.e., helping behaviors and work role performance). Future research should consider other personal support resources such as empathy and adaptability. Moreover, future researchers may also leverage the current model with organizational level support resources such as perceived organizational ethical climate. Additionally, future studies could adopt other theoretical perspectives to explain the moderating effect.

Fourth, this study was conducted in Pakistan, where most of the respondents were Muslims; they heavily emphasized religion, which affects their attitudes and behaviors (Dar & Rahman, 2020; Khalid et al., 2018). This level of emphasis on religion may be different in other countries, and religion will be of more importance in Pakistan, and we may have overemphasized it. Therefore, we call future researchers to test the model with a religiously diverse sample and other religions such as Christianity, Buddhism, etc.

Finally, as we did, it is the prevailing practice to adopt the religiosity scale developed in the western context in studies conducted in the Muslim context. Still, such scales may not represent the Muslim belief system well. However, in this study, we have followed past studies (i.e., De Clercq et al., 2017, 2021) conducted specifically in the Pakistani context. Therefore, to address this potential limitation, future studies could adopt those scales to measure religiosity in the Muslim context that is specifically developed in the Muslim context (e.g., Ul-Haq et al., 2019; Dali et al., 2019).

Conclusion

In this study, we provide initial evidence that social undermining has a positive relationship to both helping behaviors and work role performance through the expression of guilt. Moreover, the positive relation between social undermining and expression of guilt strengthened at a higher level (vs. low) of religious faith. Taken together, our model provides an understanding of how and when the social undermining may have led to less likely negative consequences. Our study contributes to the organizational behavior (business ethics) literature by exploring the relationship between social undermining and helping behaviors and work role performance by highlighting the important mediator and moderator in the workplace. This study informs future studies of how organizations can deal with social undermining and its harmful effects by encouraging employees to utilize their personal resources to mitigate its negative effects and or gearing them towards positivity.

Data Availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Arshad, M., Qasim, N., Sultana, N., & Farooq, M. (2019) How and When Abusive Supervision Could Not Translate into Unethical Behavior. In Academy of Management Proceedings, (Vol. 2019, pp. 18857): Academy of Management Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510

Berry, D. M., Bass, C. P., Forawi, W., Neuman, M., & Abdallah, N. (2011). Measuring religiosity/spirituality in diverse religious groups: A consideration of methods. Journal of Religion & Health, 50(4), 841–851.

Bowling, N. A., Eschleman, K. J., Wang, Q., Kirkendall, C., & Alarcon, G. (2010). A meta-analysis of the predictors and consequences of organization-based self-esteem. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(3), 601–626.

Burmeister, A., Fasbender, U., & Gerpott, F. H. (2019). Consequences of knowledge hiding: The differential compensatory effects of guilt and shame. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92(2), 281–304.

Clark, M. A., Robertson, M. M., & Young, S. (2019). “I feel your pain”: A critical review of organizational research on empathy. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(2), 166–192.

Dali, N. R. S. M., Yousafzai, S., & Hamid, H. A. (2019). Religiosity scale development. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 10(1), 227–248. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-11-2016-0087

Daly, V., Ullah, F., Rauf, A., & Khan, G. Y. (2017). Globalization and unemployment in Pakistan. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 7, 634–643.

Dar, N., & Rahman, W. (2020). Looking at workplace deviance with an additional perspective: Empirical evidence from Pakistan. Sarhad Journal of Management Sciences, 6(2), 201–224.

De Clercq, D., & Bouckenooghe, D. (2019). Mitigating the harmful effect of perceived organizational compliance on trust in top management: Buffering roles of employees’ personal resources. The Journal of Psychology, 153(2), 187–213.

De Clercq, D., Haq, I. U., & Azeem, M. U. (2017). Perceived threats of terrorism and job performance: The roles of job-related anxiety and religiousness. Journal of Business Research, 78, 23–32.

De Clercq, D., Haq, I. U., & Azeem, M. U. (2021). Ignoring leaders who break promises or following god: How depersonalization and religious faith inform employees’ timely work efforts. British Journal of Management. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12573

Duffy, M. K., Ganster, D. C., & Pagon, M. (2002). Social undermining in the workplace. Academy of Management Journal, 45(2), 331–351.

Eaves, L. J., Hatemi, P. K., Prom-Womley, E. C., & Murrelle, L. (2008). Social and genetic influences on adolescent religious attitudes and practices. Social Forces, 86(4), 1621–1646.

Eissa, G., Wyland, R., & Gupta, R. (2020). Supervisor to coworker social undermining: The moderating roles of bottom-line mentality and self-efficacy. Journal of Management & Organization, 26(5), 756–773.

Farrukh, M., Wei Ying, C., & Abdallah Ahmed, N. O. (2016). Organizational commitment: Does religiosity matter? Cogent Business and Management, 3(1), 1239300.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Gil-Monte, P. R., & Faúndez, V. E. O. (2011). Psychometric properties of the “Spanish Burnout Inventory” in Chilean professionals working to physical disabled people. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 14(1), 441–451.

Greenbaum, R. L., Mawritz, M. B., & Eissa, G. (2012). Bottom-line mentality as an antecedent of social undermining and the moderating roles of core self-evaluations and conscientiousness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(2), 343–359.

Griffin, M. A., Neal, A., & Parker, S. K. (2007). A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Academy of Management Journal, 50(2), 327–347.

Hair, J., Anderson, R., Babin, B., & Black, W. (2010a). Multivariate data analysis. A global perspective.

Hair, J. F., Celsi, M., Ortinau, D. J., & Bush, R. P. (2010b). Essentials of marketing research (Vol. 2). McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Hansen, D. E., Vandenberg, B., & Patterson, M. L. (1995). The effects of religious orientation on spontaneous and nonspontaneous helping behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences, 19(1), 101–104.

Haq, I. U., De Clercq, D., Azeem, M. U., & Suhail, A. (2020). The interactive effect of religiosity and perceived organizational adversity on change-oriented citizenship behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 165(1), 161–175.

Hareli, S., Shomrat, N., & Biger, N. (2005). The role of emotions in employees’ explanations for failure in the workplace. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 20(8), 683–680.

Harrison, D. A., McLaughlin, M. E., & Coalter, T. M. (1996). Context, cognition, and common method variance: Psychometric and verbal protocol evidence. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 68(3), 246–261.

Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22.

Hayes, A. F., & Rockwood, N. J. (2020). Conditional process analysis: Concepts, computation, and advances in the modeling of the contingencies of mechanisms. American Behavioral Scientist, 64(1), 19–54.

Highhouse, S. (2009). Designing experiments that generalize. Organizational Research Methods, 12(3), 554–566.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421.

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology & Organizational Behavior, 5, 103–128.

Hobfoll, S. E., & Shirom, A. (2000). Conservation of resources theory: Applications to stress and management in the workplace. In R. T. Golembiewski (Ed.), Handbook of organization behavior. Dekker.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. Mcgraw-hill.

Ilies, R., Peng, A. C., Savani, K., & Dimotakis, N. (2013). Guilty and helpful: An emotion-based reparatory model of voluntary work behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(6), 1051–1059.

Jamal, M., & Badawi, J. (1993). Job stress among Muslim immigrants in North America: Moderating effects of religiosity. Stress Medicine, 9(3), 145–151.

Julle-Danière, E., Whitehouse, J., Vrij, A., Gustafsson, E., & Waller, B. M. (2020). The social function of the feeling and expression of guilt. Royal Society Open Science, 7(12), 200617. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.200617

Khalid, M., Bashir, S., Khan, A. K., & Abbas, N. (2018). When and how abusive supervision leads to knowledge hiding behaviors: An Islamic work ethics perspective. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 39(6), 794–806.

Kirchmaier, I., Prüfer, J., & Trautmann, S. T. (2018). Religion, moral attitudes and economic behavior. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 148, 282–300.

Kovjanic, S., Schuh, S. C., Jonas, K., Quaquebeke, N. V., & Van Dick, R. (2012). How do transformational leaders foster positive employee outcomes? A self-determination-based analysis of employees’ needs as mediating links. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(8), 1031–1052.

Kutcher, E. J., Bragger, J. D., Rodriguez-Srednicki, O., & Masco, J. L. (2010). The role of religiosity in stress, job attitudes, and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(2), 319–337.

Lim, V. K. (2002). The IT way of loafing on the job: Cyberloafing, neutralizing and organizational justice. Journal of Organizational Behavior: THe International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 23(5), 675–694.

Li-tze, Hu., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: a Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Liu, W., & Xiang, S. (2018). The positive impact of guilt: How and when feedback affect employee learning in the workplace. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 39, 883–898.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128.

Mathew, G. C., Prashar, S., & Ramanathan, H. N. (2018). Role of spirituality and religiosity on employee commitment and performance. International Journal of Indian Culture and Business Management, 16(3), 302–322.

Meier, L. L., & Cho, E. (2019). Work stressors and partner social undermining: Comparing negative affect and psychological detachment as mechanisms. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(3), 359–372.

Mostafa, A. M. S., Farley, S., & Zaharie, M. (2020). Examining the boundaries of ethical leadership: the harmful effect of Co-worker social undermining on disengagement and employee attitudes. Journal of Business Ethics, 174, 1–14.

Pandey, J., & Singh, M. (2019). Positive religious coping as a mechanism for enhancing job satisfaction and reducing work-family conflict: A moderated mediation analysis. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 16(3), 314–338.

Park, J. H., Carter, M. Z., DeFrank, R. S., & Deng, Q. (2018). Abusive supervision, psychological distress, and silence: The effects of gender dissimilarity between supervisors and subordinates. Journal of Business Ethics, 153(3), 775–792.

Pierce, J. L., & Gardner, D. G. (2004). Self-esteem within the work and organizational context: A review of the organization-based self-esteem literature. Journal of Management, 30(5), 591–622.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227.

Probst, T. M., Petitta, L., Barbaranelli, C., & Austin, C. (2020). Safety-related moral disengagement in response to job insecurity: Counterintuitive effects of perceived organizational and supervisor support. Journal of Business Ethics, 162(2), 343–358.

Pulakos, E. D., Arad, S., Donovan, M. A., & Plamondon, K. E. (2000). Adaptability in the workplace: Development of a taxonomy of adaptive performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(4), 612–624.

Sikorska-Simmons, E. (2005). Religiosity and work-related attitudes among paraprofessional and professional staff in assisted living. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging, 18(1), 65–82.

Tang, T.L.-P., Sutarso, T., Davis, G.M.-T.W., Dolinski, D., Ibrahim, A. H. S., & Wagner, S. L. (2008). To help or not to help? The Good Samaritan Effect and the love of money on helping behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(4), 865–887.

Thompson, M. J., Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., & Vogel, R. M. (2020). The cost of being ignored: Emotional exhaustion in the work and family domains. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(2), 186.

Ul-Haq, S., Butt, I., Ahmed, Z., & Al-Said, F. T. (2019). Scale of religiosity for Muslims: an exploratory study. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 11, 1201.

Weaver, G. R., & Agle, B. R. (2002). Religiosity and ethical behavior in organizations: A symbolic interactionist perspective. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 77–97.

Williams, L. J., Hartman, N., & Cavazotte, F. (2010). Method variance and marker variables: A review and comprehensive CFA marker technique. Organizational Research Methods, 13(3), 477–514. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428110366036

Yue, Y., Wang, K. L., & Groth, M. (2017). Feeling bad and doing good: The effect of customer mistreatment on service employee’s daily display of helping behaviors. Personnel Psychology, 70(4), 769–808.

Zaman, R., Roudaki, J., & Nadeem, M. (2018). Religiosity and corporate social responsibility practices: Evidence from an emerging economy. Social Responsibility Journal, 14, 368–395.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Social Science Project of Fujian Province: A Study on the Mechanisms of Influence of Digital Human Resource Management System on Employees’ Psychological Alienation from the Perspective of Social Structuration theory (Project No: FJ2022B054).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Research Involving Human and Animals Rights

The sample data was based on Human.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A Constructs items

Appendix A Constructs items

Social undermining | Source |

|---|---|

How often have you intentionally… Insulted your coworker? Gave your coworker the silent treatment? Spread rumors about your coworker? Delayed work to make your coworker look bad or slow your coworker down? Belittled your coworker or your coworker ‘s ideas? Hurt your coworker’s feelings? Talked bad about your coworker behind their back? Criticized the way your coworker handled things on the job in a way that was not helpful? Did not give as much help as you promised? Gave your coworker incorrect or misleading information about the job? Competed with him for status and recognition? Let him know that you did not like him or something about him? Did not defend your coworker when people spoke poorly of your coworker? | Duffy, M. K., Ganster, D. C., & Pagon, M. (2002). Social undermining in the workplace. Academy of management journal, 45(2), 331–351 |

Expression of Guilt | |

In my conversations with coworkers… I express feelings of guilt about some of my bad attitudes at work I express how I feel bad about some of the things I have said at work I express regrets about some of my bad behaviors at work I think I should apologize to someone for my bad behaviors at work I express what I feel bad about some of the things I have said at work | Gil-Monte, P. R., & Faúndez, V. E. O. (2011). Psychometric properties of the “Spanish Burnout Inventory” in Chilean professionals working to physical disabled people. The spanish journal of psychology, 14(1), 441–451 |

Religious Faith | |

I feel like I can always count on Allah/God My faith in Allah/God helps me through hard times I feel thankful to Allah/God for my life I believe in Allah/God I ask Allah/God to help me make important decisions I feel that without Allah/God there would be no purpose in life I try to live how Allah/God wants me to live My faith in Allah/God shapes how I think and act every day My life is committed to Allah/God I believe that Allah/God sometimes punished people who commit a sin I often count my blessings Being with other people who share my religious views is important to me I am grateful for what other people have done for me I have a lot to be thankful for When people do nice things for me, I try to let know that I appreciate it I believe that if someone hurts me, it is alright to get back at them | Eaves, L. J., Hatemi, P. K., Prom-Womley, E. C., & Murrelle, L. (2008). Social and genetic influences on adolescent religious attitudes and practices. Social forces, 86(4), 1621–1646 |

Helping Behaviors | |

This employee helps coworkers who have been absent This employee orient new people even though it is not required This employee helps coworkers who have heavy workloads This employee assists supervisor with his or her work This employee helps colleagues solve work-related problems | Tang, T. L.-P., Sutarso, T., Davis, G. M.-T. W., Dolinski, D., Ibrahim, A. H. S., & Wagner, S. L. (2008). To help or not to help? The Good Samaritan Effect and the love of money on helping behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(4), 865–887 |

Work Role Performance | |

This employee carried out the core parts of his job well This employee complete his core tasks well using the standard procedures This employee ensured his tasks were completed properly This employee adapted well to changes in core tasks This employee coped with changes to the way he has to do his core tasks This employee learned new skills to help him adapt to changes in his core tasks This employee initiated better ways of doing his core tasks This employee come up with ideas to improve the way in which his core tasks are done This employee made changes to the way his core tasks are done | Griffin, M. A., Neal, A., & Parker, S. K. (2007). A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Academy of management Journal, 50(2), 327–347 |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Dar, N., Usman, M., Cheng, J. et al. Social Undermining at the Workplace: How Religious Faith Encourages Employees Who are Aware of Their Social Undermining Behaviors to Express More Guilt and Perform Better. J Bus Ethics 187, 371–383 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05284-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05284-x