Abstract

The relevance of research is that psychological research carried out after re-establishment of Lithuanian independence revealed that the consequences of the Soviet totalitarian regime are still being felt in this country to this day. The aim of the paper is to analyse happiness of Lithuanian residents. Influence of the traumas Lithuanians suffered for five decades is even passed on to the second generation. The happiness index of the Lithuanian residents has not changed for almost twenty years, though the economy of the country has considerably improved. Moroever, high suicide rates in Lithuania are also slow to change. This study aimed to analyze life satisfaction variations in a representative sample of Lithuanians (n = 1002). The results suggest that Lithuanians with high level of satisfaction with life get into a higher number and intensity of positive states; they pointed out much greater satisfaction with cultural life, satisfaction with family life, professional and occupational life, satisfaction with spiritual life, psychological state and material condition; they indicated that there are people they can talk to any time, they take pleasure in spending time with the closest ones, they think that their earnings guarantee their security. Persons of high level of satisfaction with life statistically significantly more perceive life as pleasant, valuable, and meaningful.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Psychological research carried out after re-establishment of Lithuanian independence revealed that the consequences of the Soviet totalitarian regime are still being felt in this country to this day. Influence of the traumas Lithuanians suffered for five decades is even passed on to the second generation (Vaskeliene 2012). The happiness index of the Lithuanian residents has not changed for almost twenty years, though the economy of the country has considerably improved. Moroever, high suicide rates in Lithuania are also slow to change. How much time is needed to cope with experienced psychological - cultural trauma? As denoted by DeVries (2007), trauma affected “society will never be the same”. Does that mean that individuals of post- soviet countries will carry on low levels of happiness? Are Lithuanian residents still carrying on negative attitudes towards life which generate negative emotions and affect their overall happiness? Global progress in human well-being since the end of World War II has been established in four critical sectors: the health, education, economic, and welfare sectors. Research on the transformative changes in quality of life followed accordingly (Estes and Sirgy 2019). Some authors put efforts to clarify sustainable happiness, proposing Happiness Sustainability Cycle (HSC) model (Eckhaus and Sheaffer 2018), while others discuss patterns of positive correlations between freedom and happiness (Abdur Rahman and Veenhoven 2018).

Interestingly, some studies have found that beliefs about the malleable nature of happiness (growth mindsets) are associated with well-being and if this well-being had downstream implications for satisfaction with one’s relationships, health, and job (Van Tongeren and Burnette 2018). It was empirically demonstrated that psychological maturity predicts different forms of happiness. Moreover, it has been found that kindness moderates on the relation between trust and happiness (Myers and Diener 2018), and a range of kindness activities boost happiness. Some authors focus on investigating the relationships between subjective well-being and psychological well-being over two decades (Joshanloo 2019), while others concentrate on cross-national patterns of happiness. Surprisingly, it was found that the urbanization positively affects happiness in the cross-country analysis, but in Europe, urbanization and education are not significant factors in terms of happiness.

However, empirical research demonstrates a relationship between happiness and career success: happiness is correlated with and often precedes career success and experimentally enhancing positive emotions leads to improved outcomes in the workplace (Walsh et al. 2018). Interestingly, valuing happiness enhance subjective well-being and may change with age (Wong et al. 2019). Moreover, some authors provide empirical evidence of the relation between income and mental well-being and of the possible role of personality traits in modifying this relation (Syrén et al. 2019). To sum up, recent research on happiness focus on the associations of subjective well-being with age, gender, income, personal traits, social support, and religious engagement, the benefits of happiness, and of happiness interventions at both individual and national levels (Myers and Diener 2018). Various polls, such as the World Value Survey or the Gallup Survey show that Lithuania is among the countries demonstrating the lowest scores for happiness index and the highest rate of suicide in Europe. According to the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 2014), happiness of the Lithuanian residents is almost 40% lower than the highest possible score for happiness (Table 1).

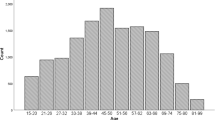

The number of people dying each year by suicide in Lithuania per 100,000 residents amounted to 61.3 in men and 10.4 – in women (World Health Organisation n.d.). Two decades earlier, the hypothesis could be made that such indices may be explained scientifically in accordance with the theory of Durkheim et al. (2010) on the impact of political changes and economic crisis on psychological health of society and on changes in people’s well-being during economic transition periods. Nevertheless, the economy of Lithuania over the two last decades kept growing, its political system became stable as compared to 1991, the rate of suicide of the Lithuanian people, however, have remained almost unchanged. Happiness index has not changed much either. According to the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 2014), subjective happiness of the Lithuanian residents since 2001 has changed only slightly (See Fig. 1, Table 2).

A. White (quotation as per Forgas 2006) analysed more than 100 surveys which involved around 80,000 respondents from different countries of the world. The happiest countries of the world in the order of ranking are as follows: Denmark, Switzerland, Austria, Iceland, the Bahamas, Finland, Sweden; the USA according to happiness takes the 23rd position, the UK features at position 41, China – 82, Japan – 90, India – 125, Russia – 167. The three unhappiest countries are: Congo, Zimbabwe and Burundi. Surprisingly, for the decades Lithuania has been among unhappiest countries in Europe.

Happiness index of the Lithuanian residents which has almost not changed for twenty years, though the economy of the country has grown, shows that new scientific explanations of the happiness phenomenon and constructive scientific and political solutions are required. Although, as discussed, scientists have developed a number of definitions of subjective, psychological well-being, this paper mostly referred to those theories which suggest measuring various structural components of subjective well-being – both cognitive (life satisfaction, assessment of life and its areas) and emotional (emotional experience). On the basis of scientific literature, we formulated hypotheses that the groups of high and low subjective well-being of the Lithuanian residents statistically are substantially different according to emotional states experienced over the last week, satisfaction with diferent fields of life and importance attributed to them. The aim of this article is to analyse happiness of Lithuanian residents. It will use the concept of happiness in life encompassing emotional and cognitive modalities of subjective assessment of life experiences as defined by Martin Seligman (Seligman 2011). With reference to academic literature, we have formulated hypotheses that the groups of high and low satisfaction with life Lithuanian residents differ in their profiles. However, in this article we do not analyze socio – demographic or economic factors which might be related to variations in results.

The semantic range of concepts used in the studies on happiness is remarkably wide – it includes the connotations of subjective well-being as of ʻcognitive and emotional assessments of life, pleasant emotional experiences, immense life satisfaction’ (Diener et al. 2003), of psychological well-being as of ʻrealisation of real potentials of a person, living one’s life the way one wants’ (Hayborn 2008), ʻsetting and pursuing goals, experiencing deep relationship with others, managing requirements and opportunities of the surrounding environment, positive self-respect’ (Ryff and Singer 1996), of happiness as of positive complex emotional state, of happiness in life as of unconditional ʻprocess of creating and feeling the meaning’ of life (Graham 2011), of satisfaction with life as of subjective cognitive evaluation of different areas of life at different moments of life taking into consideration life events, of quality of life as of ʻsubjective evaluation of own life’ (Christensen et al. 2013). The variety of notions means that the examined phenomenon is complex, multifold and, though every concept falls into the same set of the construct, it denotes slightly different, interrelated and overlapping elements of this set.

Theoretical Overview

One of the currently best known integrated theoretical models of happiness in life by Martin Seligman (2002) which has been used as the basis for establishment of a widely-known school for life quality therapy focused on interventions to life quality (Frisch 2006) was developed on the grounds of Benthamistic and Aristotelian philosophical concepts. According to the model of Martin Seligman (2002), happy life is composed of three constituents, namely, 1) pleasure, 2) meaningfulness and 3) engagement. In other words, life can be called happy, if: 1) positive emotions in life exceed negative ones (balance between positive and negative), an individual can say that part of his/her experiences are pleasant, s/he has an opportunity to get pleasures, enjoy them, s/he can sincerely admit that “it feels good to live”, though life is full of challenges; 2) an individual realises the meaning of his/her life, sees his/her goal as being of service to humanity and pursues it, s/he can frankly admit to seeing the meaning in every event of his/her life, even those which cause suffering because human pain and suffering may lead to personal development and growth; s/he realises the meaning in personal development, improvement and wants to help others develop; 3) an individual lives a life which enables him/her to maximally involve in all life experiences, to live in “the flow”, to concentrate 100% to “here and now”, besides, all this is done because s/he likes doing what s/he does, “loses the sense of time”. According to the latest five-element PERMA model by Mr. Seligman, happiness is determined by 1) positive emotion; 2) engagement; 3) relationship; 4) meaning; 5) accomplishment (Seligman 2011).

Meanwhile, the model of Ed Diener defines subjective well-being as “cognitive and affective measurements of a person’s own life. These assessments include emotional responses to events, also cognitive solutions and affective evaluations of satisfaction and accomplishment. Subjective well-being involves experiencing pleasant emotions, low level of negative emotions, immense life satisfaction” (Diener and Seligman 2004). To put it differently, subjective well-being encompasses (1) emotional responses to life events, (2) general evaluation of life satisfaction, (3) contentment with specific important areas of life (Diener et al. 1985).

Scientific research shows that objective factors, such as health, amenities, reward for work, etc., have influence on how we experience and realise subjective well-being; it does not, however, mean that they determine it (Kelloway et al. 2013). Many authors state that psychological well-being is subjective, this means that satisfaction with various areas of life, work, social relations, his/her personality, health, etc. can be best evaluated by the person him/herself; nevertheless, psychologist Daniel Kahneman et al. (1999) claims that well-being may be also objective. As he suggests, one needs to calculate the mean of emotional assessments over a certain period of time and the result will illustrate quite an objective level of happiness (Kahneman et al. 1999). Besides, Kahnemann says that evaluating objective factors might help identify, whether a person feels happy. On the other hand, objective well-being loses meaning, for instance, in case of endogenic depression, when external conditions seem to allow a person to enjoy life but the level of subjective well-being is low.

Happiness or unhappiness is short-term emotional and sensorial responses to life events. According to the authors, a person’s mental system tends to maintain homeostasis, however, due to emotionally significant life events – both positive and negative – a person deviates from homeostatic state. If experiences are positive and cause positive emotions (joy, comfort), a person’s well-being is seen as being high, whereas, if experience is negative and causes negative emotions (sadness, anger, anxiety), its evaluation is low. Still, eventually a person adapts to the changed circumstances, and emotionality (both positive and negative) gets back to the initial homeostatic (neutral) level. This is evidenced by various research: lottery winners are not happier than ordinary people. Moreover, even after backbone lesion, people tend to return to their usual state of happiness quite soon. Thus people adapt to the winning in a lottery and even to paralysis.

In other words, happiness adaptation model, having experienced unordinary events a person may for some time feel emotional outcomes, however, eventually the positive or negative emotional background fades away and the person adapts to the new circumstances without attaching much significance to them. Certainly, though researchers claim that the adaptation process takes little time, it would be unrealistic to think that people will completely adapt to any circumstances. As a result, this theory was much criticised because not all persons who have underwent emotionally strong (positive or negative) events, return to the primary neutral condition (Diener 2000). In addition, for example, the experience of a crisis or psychological tauma (emotionally strong negative event) may cause post traumatic growth to some persons but be destructive and lead to depression to others.

According to Carol Ryff, psychological well-being means “the pursuit of perfection which reflects the realisation of real potentials” (Ryff and Singer 1996). C.D. Ryff, just like other representatives of eudaemonic tradition, states that the fact that a person feels good and is happy is not sufficient for person’s full operation, it is necessary to take into consideration self-expression, growth and similar constructs (Ryff and Singer 1996). The eudaemonic theory developed by Ryan and Deci (2000) states that psychological well-being is related to the fulfilment of three psychological needs – autonomy, competence and coherence. If all these needs are satisfied, a person may be said to have a high level of psychological well-being. The theoretical model was further developed in 2000 (Ryan and Deci 2000). The authors claim that every healthy person is born with the potential of activeness and initiative. Small children explore the environment intensively, “try”, learn and they like it. They play without any encouregament, they build sand castles without expecting to get any reward, they like the change of stimuli, and they avoid boredom. They like to act because activities help them feel and measure their possibilities (realisation of the need of competence) and get positive emotions.

According to Ryan and Deci (2000), for a person to be happy s/he has to feel free from external pressure and be autonomous in choosing the field of activity. Many authors agree with this statement (Kelloway et al. 2013) saying that through his/her lifetime every human-being seeks for greater autonomy and everyone has a need to self-determine (self-determination). Ryan and Deci (2000) think that people usually try to look for the environment which would allow them to fulfil their need for autonomy (except for dependable personalities). Some endeavour to create such environment themselves. The need for autonomy means that a person wants to feel that s/he is a powerful, influential participant in encountered situations and if s/he succeeds, s/he gets positive emotions, feels motivated and happy. That this attitude is right prove zoo-psychological tests: tests carried out by Maltseva (2018) showed that monkeys like motor activities with puzzles, even if they are not rewarded for acting, i.e. are not given any food; and what’s more – they prefer playing, if they want and are not encouraged by food. Deci and R. Ryan substantiate their theoretical model by research and theories of other authors: for instance, Maltseva (2012, 2014) argued that every act/movement a person makes is intended for trying to affect the environment and gain satisfaction through this activeness. If situations in which a person participates cause him/her to experience helplessness, naturally, a desire to withdraw from them arises becauses/he feels unhappy. Thus following the self-determination theory, people are inherently active and like challenges, they like exploring new opportunities and trying their own competencies, they strive for variety of stimuli. If they do not get all the aforementioned, they learn what helplessness is and become unhappy. To say it another way, E. Deci and R. Ryan state that to feel well-being satisfaction or emotions is not enough, an individual has to materialise his/her real potentials, or daimon (Ryan and Deci 2000).

Happiness does not emerge from nowhere, a person may create this feeling, it is related with experience of “optimal” flow. The experience of flow is a state when a person feels completely submerged in what s/he is engaged in, s/he never feels bored, s/he gains satisfaction in doing that, s/he has clear goals, is conscious and is not afraid of making mistakes. The president of the American Psychological Association M. Seligman (2002) raised 3 questions: 1) “What determines that some moments in life give more pleasure than other?”, the focus is put on: the past (subjective well-being, satisfaction), the future (hope and optimism), the present (joy and current); 2) “What distinguishes a happy individual from an unhappy one?”, the interest lies in positive features of a person, such as ability to love, vocation, courage, social skills, sensibility, stamina, forgiveness, originality, spirituality, talent, or wisdom. 3) “What social context promotes happiness?”; civil values are analysed: responsibility, altruism, tolerance, professional ethics, etc. M.B. Frisch (2006) asserts that satisfaction in life equalised to the quality of life is based on subjective assessment of an individual’s desires, needs, aims and level of accomplishment. That is to say, life satisfaction is conformance between what a person wants and what s/he has. The lesser the difference between the accomplishments and desires of a person, the greater his/her life satisfaction. This could be expressed by the following formula:

where

- SL:

-

means life satisfaction;

- A:

-

means aspirations and desires;

- R:

-

means accomplishments, results.

Source: developed by the authors.

M.B. Frisch (2006) states that general quality of life of an individual is the total of satisfaction with different areas of life which are valued by a person and which are important to him/her. An individual’s satisfaction in every area of life is composed of four elements as follows:

-

1)

characteristics and conditions of an objective situation. For example, an objective situation affecting an individual’s satisfaction with work is composed of reward, relationship with colleagues and management, work tasks, working environment and the like;

-

2)

the understanding of a situation and its acceptance affected by an individual’s attitudes and traits has an especially big influence of an individual’s satisfaction with a certain area of life in those moments when a person perceives the situation inadequately because s/he measures it too negatively or excessively positively;

-

3)

individual evaluation of accomplishments in a concrete area of life based on personal beliefs about what the success is. The reality seen from an individual’s perspective is compared to the desired accomplishments in a particular field of life and in this way a person decides, whether s/he feels satisfaction with a particular area of life; 4) meaning and significance of an area of life in a person’s life satisfaction. Some areas of life are more important than other, therefore, the theory of quality of life says that before assessing the total person’s life satisfaction, first the importance of each particular area shall be evaluated which determines the effect the area has on general life satisfaction. The greater importance is attributed to a particular field of life, the greater effect on general satisfaction of life it has.

Thus M. Frish claims that life satisfaction is the most important aspect of psychological well-being (Frisch 2006). He points out that people who have high quality of life account for around 20% of population. These are exceptionally happy people who succeed in anything they do, who are capable of achieving everything they want in every (almost every) area of their life. Such people build successful relationships and create life which gives them pleasure and satisfaction. It is thought that people with high quality of life cope with psychological stress flexibly because they get quite a lot of psychological and social assistance from the people round about. They are capable of solving problems and know how to defend themselves so as to improve their life situation. Ability to look at the world constructively when faced with problems helps them not to succumb to negative emotions. Summarising the concepts of various authors, theories of psychological well-being or happiness may be categorised into several major models. The so-called goal theories state that happiness is the state when a goal is accomplished. This position is reasoned by the fact that some authors point out that asseesing their lives people often take into consideration, whether they managed to achieve their goals. For instance, 31% of respondents took into account their goal when asseesing their life satisfaction. We feel happy when we attain our goals and unhappy when we fail. According to the goal theories, approaching to the achievement of goal should improve the subjective well-being; meanwhile, the absence of progress should have a negative effect on subjective well-being.

In goal theories a goal is defined as a final result which a person tries to achieve and maintain. Having goals affects our behaviour and functions as a comparative standard. Our goals and desires are especially important to us, they have a huge effect on subjective well-being. Some goals have no clear final results (for instance, “be famous”, “become rich”) but even trying to achieve hardly attainable or intangible goals, people feel happy, which means that it is not the accomplishment of a goal but rather the process, movement towards the goal is related to psychological well-being. Approaching to goals may determine the increase in life satisfaction. Actually, attaining material goals will not necessarily determine higher subjective well-being, especially, if consideration of other needs decreases due to material goals (Ryan and Deci 2000).

Research results show that subjective well-being may be improved not only by approaching to goals but also by the fact of having important resources for achievement of goals. Diener (1994) found out that ensuring important resources improves subjective well-being more than the possession of insignificant resources. Material aspiration of people of up to certain age grew faster than their financial capabilities, though with years’ people would usually had accumulated a considerable amount of material goods. Seligman (2002) claim that increasing material needs and desires will lead to unsatisfaction; meanwhile, capability to fulfil needs according to income speaks of greater life satisfaction. As Diener (2003) state, the growth in needs along with material aspirations may explain why increasing income do not increase the level of subjective well-being.

Therefore, according to goal theories, the feeling of happiness occurs when a deliberate goal is achieved. Yet, these theories raise a lot of doubts and related issues. A person may even not realise consciously what goals are the most important to him/her, though happiness depends on their fulfilment (Diener et al. 1985). Besides, one could also consider which goals may have greater effect – short-term or long-term. In addition, goals may contradict each other. According to Diener, happiness depends not only on achievement of goals but also on their successful integration (Diener et al. 1985). Thus goal theories have a lot of drawbacks as they are not clearly formulated and can be easily verified; they, however, provide quite an interesting explanation what type of people become happy and how.

Theories that are related to the goal theories are needs theories. Their main idea is that the more the needs are fulfilled, the happier a person should be. According to Diener (1994), happy and prosperous societies capable of satisfying the basic needs can usually be characterised by longevity, low rates in baby mortality, clean water and food, their members are better educated and have more civil rights. As the latest research on well-being show (Diener et al. 2010), fulfilment of basic needs has a huge positive effect on people’s well-being. Graham (2011) identified that satisfaction of psychological needs influences positive and negative emotionality. According to Ryan and Deci (2000), the needs of close social relationships, excellence and autonomy are universal in many countries and may determine greater life satisfaction. Although the representatives of needs theories recommend to respond to needs and desires, if we want to be happy, the supporters of other theories suggest to suppress them; confusion, however, occurs when we try to decide which needs and desires are the most important and to what extent they have to be satisfied (Diener et al. 1985). Besides, researches demonstrate variations of correlation between fulfilment of needs and subjective well-being. Let us suppose that revenue in low-income groups have a bigger effect on psychological well-being than in high-income groups (Diener and Seligman 2004). The pursuit of inner needs positively affects subjective well-being; meanwhile, the pursuit of external needs may have a negative effect. Still, these theories also have their demerits. Following them, it is diffuclt to explain, why the level of well-being does not increase with the growth of economy or why it increases less than the level of living standards (Diener and Seligman 2004).

In addition, there are theories of comparable standards which also seem very interesting. According to these theories, the absolute expression of fulfilment of needs is important but the greater effect is made by how the available resourses are compared to the resources of those around or what is the change in the available resources (Diener 2000). For instance, the theory of social comparison states that people take into account other persons as comparable standards. Happiness will occur when we surpass others who may be both exceptionally good at something and ordinary people. Certainly, not all persons can be referred to as comparable standards as there are differences in age, gender and other aspects. Theories also say that regardless of whether we want that or not we tend to compare ourselves with certain standards (Kahneman et al. 1999). It does not matter what kind of objective event takes place; however, if we surpass the standards we set we are filled with happiness. The standard may be an invididual’s past. Each new event is compared to the usual level of happiness. Thus if an event causes more positive outcomes, we will feel happy. Still high aspirations are factors which prevent happiness since they are too hard to be achieved. The more aspirations and practical conditions coincide, the happier the person is (Diener 2000).

Although the theories of comparable standards are quite popular and help explain certain changes in well-being, they are also much criticised. For example, a person who suffers may not want to compare him/herself with others. The fact that another person suffers more does not necessarily reduce your pain (Diener 1994). One more example: research results show that the absolute total of income has a greater effect on the feeling of subjective well-being than comparable income within the country (Diener et al. 2010). On the other hand, these theories help explain such phenomena as hedonic adaptation, when getting used to the increased level of income or change in expectations does not increase but rather reduce the level of subjective well-being (Diener 2000; Nagimzhanova et al. 2019).

The theories of activity explain happiness differently from the needs, comparable standards or goal theories. According to them, happiness occurs as a by-product when a person is involved in certain activity (Diener 1994). Aristotle was one of the first to emphasise that for a person to find happiness, certain personal abilities and traits have to be revealed. The activity theories stress that happiness is achieved when we are actively engaged in certain activities for the purpose to be happy, when we think positively (consciously control positiveness of thinking) (Aristotle n.d.), live in the state of “flow”, when activities meet our abilities (if activities are too easy, we will be bored; if they are too difficult, we will become worried). From the bottom to the top theory defines happiness as totalling of “pleasures” and “pains” made by brain. To feel happy, we have to deliberately pay attention to happy moments in our lives, to look for them or create them (Diener 2003). The opposite theory is from the top to the bottom approach which prepares individuals to accept, assess and respond to events more positively. This attitude assumes that a personality is the main factor affecting reactions to events. From the top to the bottom approach states that people prone to depression are unable to see pleasures in their daily life, meanwhile, from the bottom to the top approach says that depression is caused by the shortage of happy moments in life. To summarise, for the meantime, there is no integrated and universal happiness theory, thus to analyse the phenomenon which is the focus of the article we will refer to different theoretical models.

Methodology

The happiness survey of the Lithuanian residents was carried out by the method of multi-stage random sampling. To put it differently, the selection of respondents was organised so that every Lithuanian resident had equal chances of being surveyed. All participants were personally asked to take part in the survey; the method of survey used was interviews at the respondents’ homes. The survey was carried out from April 11 to 23, 2014, in Vilnius, Kaunas, Klaipeda, Siauliai, Panevezys, Druskininkai, Kretinga, districts of Alytus, Sakiai, Pakruojis, Utena, Taurage, Svencionys, Raseiniai, Kupiskis, Akmene, Rokiskis, Lazdijai, Telsiai, Mazeikiai, Marijampole, Anyksciai, Varena, Moletai and Ukmerge. The survey took place in 20 cities and 29 villages.

The total number of respondents amounts to 1002 people, 469 men (46.8%) and 533 (53.2%) women, but in this paper we present data obtained from 306 respondents. The average age of the respondents is 49.29 (the respondents were aged from 18 to 90, standard deviation being 16.206). Most of respondents were married (48.9%), some of them lived with a partner (9.7%), some were divorced (12.2%), some were widowed (13.8%) or lived alone (12%). Most of respondents had higher education (51.4%), however, there were some whose education was primary (2.7%) or secondary (6.5%). Monthly income of the interviewed Lithuanian residents for a family (before taxes) accounted for as follows: less than LTL 1500 – of most of the respondents (44.7%), from LTL 1501 to LTL 3000 – of some of the respondents (37.4%), from LTL 3001 to LTl 6000 – of a handful of respondents (13.3%), more than LTL 6001 – of 2.2% of the respondents, and more than LTL 20,000 – of 0.1% of the respondents.

This paper presents just some selected results of the overall survey on Lithuanian residents’ quality of life. To draw up the questionnaire on the happiness of the Lithuanian residents’ various instruments of measurement and assessment were used as follows:

-

1)

to measure subjective well being the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) was used. The scale (Diener et al. 1985) is one of the most popular to measure life satiscation in different countries of the world. It is based on five statements which have to be assessed using the Likert scale of answers from ‘I completely disagree’ to ‘I fully agree’. The life satisfaction scale has been verified in different social contexts (Graham 2011). The internal consistency of the life satisfaction scale in this research was quite high: Cronbach’s alpha for the estimate of the respondents of the Lithuanian population was α = .89 (n = 1002).

-

2)

to assess positive and negative emotions, the Positive, Negative and Suicidal Risk Related States Scale was used. This scale was modified by the authors of the questionnaire for the survey of happiness of the Lithuanian residents using the variant of the PANAS scale which is composed of 22 statements measuring emotional states. The respondents had to evaluate how strongly they felt one of the specified states over the last week. Statements were measured in the Likert scale from ‘I did not’ to ‘I felt the emotion very often and it was very strong’. The internal consistency of the Positive, Negative and Suicidal Risk Related States Scale and subscales in this survey were quite high: Cronbach’s alpha for the Positive States Subscale (9 components: joy, gratitude, enthusiasm, hope, trust, sensibility, optimism, happiness, comfort/calmness) for the estimate of the residents among the Lithuanian population was α = .94; Cronbach’s alpha for the Negative States Subscale (8 components: grievance, anger, anxiety, psychological pain, guilt, sadness, fear, stress) for the estimate of the residents among the Lithuanian population was α = .90; Cronbach’s alpha for the Suicidal States Subscale (5 components: unwillingness to live, despair, hopelessness, meaninglessness, shame) for the estimate of the residents among the Lithuanian population was α = .89 (n = 1002).

-

3)

to evaluate the attitude towards life of the Lithuanian residents the Life Perception Scale was drawn up. This eight-statement scale was intended to analyse specific beliefs people have in relation to their subjective well-being and it was designed in accordance with the writings by positive psychology researchers (Diener 1994, 2000, 2003; Diener et al. 1985, 2003, 2010; Diener and Seligman 2002; ; Frisch 2006; Ryan and Deci 2000; Ryff and Singer 1996; Seligman 2002; Sirgy and Wu 2009; Sirgy 2012; Warburton 1996; Veenhoven 2003). The statements in the scale were asked to be measured on the basis of the Likert scale choosing from answers varying from ‘I completely disagree’ to ‘I fully agree’. Some of the statements in the scale were as follows: ‘Life is nice and enjoyable’, ‘Life is meangingful’, ‘Life is worth living’. The internal consistency of the life perception scale in this research was quite high: Cronbach’s alpha for the estimate of residents of the Lithuanian population was α = .87 (n = 1002).

-

4)

to assess the opinion of the Lithuanian residents on suicide and suicidal thoughts the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire was developed. The statements in the scale were asked to be measured on the basis of the Likert scale choosing from answers varying from ‘I completely disagree’ to ‘I fully agree’. Some of the statements in the scale were as follows: ‘I seriously think of a suicide as of a possible way out of my problematic situation’, ‘A person has the right to kill him/her self, if s/he does not want to live anymore’. The internal consistency of the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire in this research was quite high: Cronbach’s alpha for the estimate of residents of the Lithuanian population was α = .70 (n = 1002).

-

5)

the survey on happiness of the Lithuanian residents also used the Life Domains Importance and Satisfaction Scale created by the authors of the research. The internal consistency of this scale was sufficient: Cronbach’s alpha for the estimate of residents of the Lithuanian population was α = .65 (n = 1002).

Results

Authors used SPSS 23.0 programme for data analysis. As the data was non-normally distributed, we used nonparametric Mann Whitney statistical criterion to compare the groups. To find insightful explanations of happiness and unhappiness of the Lithuanian residents we used K means cluster analysis and then selected two groups of the residents according to final cluster centers in the Satisfaction with Life Scale of Ed Diener, namely, a group of Lithuanian residents with the highest level of satisfaction with life (final cluster center M = 4.41, n = 149) and the one with the lowest level of satisfaction with life (final cluster center M = 2.81, n = 157). As Shapiro – Wilk normality test showed that results are not distributed normally (p < 0.05), nonparametric statistics was applied. The comparison of these two groups (Mann-Whitney U analysis) revealed statistically significant differences between the groups.

Mann – Whitney U test indicated, that people with high level of satisfaction with life experience more positive emotional states (joy, gratitude, enthusiasm, hope, trust, happiness, peacefulness) (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 96.53 and 213.53, respectively; U = 2.75, Z = −11.57, p = 0.000, r = 0.66). Meanwhile, the persons with low level of satisfaction with life, on the contrary, experience negative emotional states (anxiety, guilt, sadness) (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 191.18 and 113.80, respectively; U = 5.78, Z = −7.65, p = 0.000, r = 0.43), as well as suicidal states (meaninglessness, despair) more frequently and more intensively (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 191.01 and 113.97, respectively; U = 5.80, Z = −7.72, p = 0.000, r = 0.44).

Satisfaction with various areas of life among high level of overall satisfaction with life and low level of satisfaction with life of the Lithuanian residents was found to be statistically significantly different as well. The group of high level of satisfaction with life pointed out significantly greater satisfaction with cultural life (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 112.62 and 196.57, respectively; U = 5.28, Z = −8.59, p = 0.000, r = 0.49), satisfaction with family life (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 103.16 and 206.54, respectively; U = 3.79, Z = −10.60, p = 0.000, r = 0.60), satisfaction with professional, occupational life (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 102.45 and 207.30, respectively; U = 3.68, Z = −10.60, p = 0.000, r = 0.60), satisfaction with spiritual life (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 109.48 and 199.88, respectively; U = 4.78, Z = −9.25, p = 0.000, r = 0.53), satisfaction with psychological state (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 102.18 and 207.57, respectively; U = 3.64, Z = −10.74, p = 0.000, r = 0.61), satisfaction with material condition (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 93.62 and 216.59, respectively; U = 2.29, Z = −12.42, p = 0.000, r = 0.71). As we see, the effect sizes (r) are from medium to large.

Authors further analysed how various cognitive schemes (beliefs, attitudes to oneself and life itself) and experiences differ among the groups of high and low level of satisfaction with life. Mann – Whitney U test indicated that the group of the Lithuanian residents with high level of satisfaction with life statisticaly significantly differ from the group with low level of satisfaction with life according to the clarity of the goals of life (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 96.53 and 213.53, respectively; U = 2.75, Z = −11.57, p = 0.000, r = 0.66), perception of oneself as of a happy person (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 88.45 and 222.05, respectively; U = 1.48, Z = −13.49, p = 0.000, r = 0.77); estimations of spiritual comfort and completeness (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 98.33 and 211.63, respectively; U = 3.03, Z = −11.42, p = 0.000, r = 0.65). Besides, they pointed out that there are people they can talk to any time (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 117.29 and 191.65, respectively; U = 6.01, Z = −7.55, p = 0.000, r = 0.43), they spend their free-time with close people (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 121.93 and 186.77, respectively; U = 6.74, Z = −6.78, p = 0.000, r = 0.38), they think that their income guarantees their security (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 96.48 and 213.58, respectively; U = 2.74, Z = −11.80, p = 0.000, r = 0.67).

The psychological profile of the group with low level of satisfaction with life can be characterised by the following factors: they currently feel strong emotional pain (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 188.89 and 116.21, respectively; U = 6.14, Z = −7.38, p = 0.000, r = 0.42), they have a positive attitude towards suicide (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 165.40 and 140.96, respectively; U = 9.82, Z = −2.56, p = 0.010, r = 0.15), they have seriously considered the possibility of suicide as the way out of troubles (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 176.63 and 129.12, respectively; U = 8.06, Z = −5.33, p = 0.000, r = 0.30), they often feel tired and are short of energy (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 180.05 and 125.52, respectively; U = 7.52, Z = −5.51, p = 0.000, r = 0.32).

The analysis of the research results revealed statistically significant differences between the groups of high and low level of satisfaction with life with regard to the perception of life. Mann – Whitney U test indicated that people with high level of satisfaction with life perceive their life as pleasant (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 87.37 and 223.18, respectively; U = 1.31, Z = −13.74, p = 0.000, r = 0.78), valuable (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 105.34 and 204.24, respectively; U = 4.13, Z = −10.18, p = 0.000, r = 0.58), see their future in bright colours (with optimism) (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 98.01 and 211.97, respectively; U = 2.98, Z = −11.51, p = 0.000, r = 0.66), point out having been satisfied with their life 10 years ago (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 134.65 and 173.37, respectively; U = 8.73, Z = −3.95, p = 0.000, r = 0.23), hope to be satisfied with their life 10 years later (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 104.98 and 204.62, respectively; U = 4.08, Z = −10.04, p = 0.000, r = 0.57), perceive life as meaningful (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 97.01 and 213.03, respectively; U = 2.82, Z = −11.74, p = 0.000, r = 0.67), make sense of sufferings experienced in life (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 121.58 and 187.13, respectively; U = 6.68, Z = −6.62, p = 0.000, r = 0.38), are confident about themselves and strongly believe they will cope with troubles in life successfully (The mean ranks of low and high satisfaction with life groups were 102.06 and 207.70, respectively; U = 3.62, Z = −10.69, p = 0.000, r = 0.61).

To summarise, the psychological profile of a happy Lithuanian resident is composed of the following: positive emotional states experienced lately (hope, gratitude, enthusiasm, peacefulness, joy, trust), satisfaction with different areas of life, positive attitude towards his/her life in past, present, and future (life is perceived as unconditionaly meaningful and valuable).

Discussion

International scientific researches on the quality of life of societies and individuals involve the systems of objective and subjective levels of indices. In the assessment of objective system, no consideration is taken into the extent a person is satisfied with a certain area of his/her life or with his/her life in general; however, factors and circumstances of different areas of life are analysed. They are compared with the ‘ideal’ standard of the derived dimension, for instance, the limits of cholesterol level, ‘regular’ and ‘deviated from the standard’ body mass index are established. In accordance with this system, first the ‘ideal’ standard of the factors of every area of life is established, a concrete formula is worked out and only then, it is verified, whether the quality of life of an individual person meets the established standard. In this paper, however, we haven’t analyzed the effects of objective factors like income levels, physical health, housing conditions, etc. The subjective system of indices may be measured by analysing a person’s opinion of and satisfaction with various areas of his/her life. As aforementioned, subjective well being includes (1) emotional responses to life events, (2) general assessment of life satisfaction, and (3) satisfaction with specific important fields of life (Diener et al. 2003). Most often the respondents are asked to meassure their satisfaction in general or in different areas of life choosing one of the suggested answers of the Likert scale (from ‘absolutely no’ to ‘absolutely yes’), and we used this approach in the presented study.

Reseachers point out that it is necessary to analyze both the subjective and the objective levels of quality of life as their inter-relation may be very weak. There is an interesting so-called ‘disability paradox’ in scientific literature: people whose various functions are severely damaged due to illness point out that their quality of life is no worse than the one indicated by healthy people (Quick et al. 1997). Study which surveyed people with incurable cancer by means of an individualised questionnaire on quality of life showed that almost all of them pointed out that taking care of their families was more important to their quality of life than their health. This phenomenon may be explained by psychological adaptation. Once the condition of health changes, subject to a person’s character features, the change in perception, behaviour, inner standards and values takes place. This, in turn, results in ‘response bias’, i.e. shift in individual meaning of quality of life due to changes in internal standards and values.

There is also an opposite ‘response bias: when asked to assess their quality of life before the kidney transplant procedure patients evaluated it worse after it was carried out. Before the procedure they had resigned themselves to their condition, therefore, their assessment of their quality of life was better. To summarize, objective factors affect the feelings of satisfaction with life but do not necessarily determine it. Objective well-being has no sense, for example, in case of endogenous depression: external conditions would allow a person to take pleasure in life but s/he may assess his/her psychological well-being as very poor. On the other hand, an objectively mentally unhealthy delirious person may be subjectively completely satisfied with his/her life and evaluate his/her psychological well-being as excellent. Having in mind current trends in research on happiness, we assume analyzing only subjective factors to be a serious limitation of this study. Interestingly, some researchers point out that the subjective life satisfaction may depend on the respondent’s mood. Daily events may strongly affect one’s mood. On the other hand, some authors would argue that emotional states are affected not by events but rather by how people interpret them (Brown et al. 2000). However, we haven’t analyzed in this study the effect of attitudes towards life on emotional states or satisfaction with life.

The results of the analysis of life satisfaction and socio-demographic indicators are no less interesting. Diener and Seligman (2004) found out that the level of life satisfaction is relatively similar in all age-linked periods of an adult individual. Life satisfaction of women in Malaisia differs subject to their age. Minnesota is one of the happiest states in the world where the link between the life satisfaction and age is expressed by a U-shaped curve. Life satisfaction is affected by such factors as marital status, having a job or unemployment, losses, etc. People who describe themselves as happy are often social, extravert and opmistic. A survey by Brown et al. (2000) revealed that people whose life is environmentaly-friendly are usually happier. Other positive examples of subjective life quality indicators might be as follows: very interesting and highly-paid job, satisfaction with marriage and family life. Participants of an international survey (92% men and 87% women older than 45) claimed that good relationship with a spouse or a friend is especially important for the quality of life. However, in this paper we haven’t analyzed the effect of socio- demographic indicators on satisfaction with life, and we presume it is also a considerable limitation.

Summarising, surveys show that happy and content with life people are proud of their job, live a healthy lifestyle, maintain good family relationships, easily manage stress and find time for leisure (Quick et al. 1997). The fact that people feel happier when they achieve what they want shows that goal accomplishment makes people happy (Walsh et al. 2018). Positive emotions activate internal resources, promote positive behaviour and develop skills: sociability and activeness, altruism, positive attitude towards oneself and other people reinforces immune system, improves conflict resolution skills (Quick et al. 1997). Yet, though a lot of heed is paid to surveys and research on psychological well-being and they are analysed on different levels, the results of some surveys are complicated to explain, they are unambiguous, they cannot be referred to in forecasting or modelling the processes of strengthening subjective well-being in different socio-cultural environments.

In carrying out the research on happiness of the Lithuanian residents, we referred to scientific literature and developed hypotheses that the groups of high and low level of subjective well-being of the Lithuanian residents are statistically significantly different in terms of emotional states experienced over the last week, satisfaction with various areas of life, attitude towards different life aspects. All these hypotheses were confirmed and the survey carried out complemented the insights of other authors on cognitive and emotional pecularities of a happy and unhappy person (Brown et al. 2000; Christensen et al. 2013).

Conclusion

The comparison of the high level satisfaction with life and low level satisfaction with life groups unveiled statistically significant emotional differences, differences in satisfaction with different areas of life and life perception. Persons with high level of satisfaction with life get into a higher number and intensity of positive states such as gratitude, peacefulness, hope, enthusiasm, trust, and, contrariwise: people with low level of satisfaction with life experience negative emotional states (anxiety, guilt, sadness), among them – suicidal states (meaninglessness, dispair), more frequently and intensively. The groups of high and low level of satisfaction with life statistically significantly differ in satisfaction with various areas of life. People with high level of satisfaction with life pointed out much greater satisfaction with cultural life, satisfaction with family life, professional and occupational life, satisfaction with spiritual life, psychological state and material condition.

Lithuanian residents falling within the group of high level of satisfaction with life statistically significantly strongly differ from the group of low level of satisfaction with life in terms of clarity of goals in life, perception of oneself as happy, estimations of spiritual calmness and completeness; in addition, they indicated that there are people they can talk to any time, they take pleasure in spending time with the closest ones, they think that their earnings guarantee their security. The psychological profile of the low level satisfaction with life group can be characterised by the following factors: they currently experience strong emotional pain, they have a positive attitude to suicide, they have seriously considered suicide as the way out, they are often tired and lack energy. Persons of high level of satisfaction with life are statistically significantly more perceiving life as pleasant, valuable, see their future in the eyes of optimism, point out having been happy 10 years ago and hope to be happy 10 later, perceive life as meaningful, give meaning to sufferings experienced in life, are self-confident about coping with troubles in their life successfully.

In accordance with the data of the representative sample of the research on the variations in happiness of residents of Lithuania, to increase happiness of the Lithuanian residents and reduce suicide rates, it is recommended to start special interventions to reinforce the belief of the society in its powers, to strenghthen societal and individual self- efficacy, hope, optimism, and resilience.

Change history

29 June 2023

This article has been retracted. Please see the Retraction Notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04913-6

References

Abdur Rahman, A., & Veenhoven, R. (2018). Freedom and happiness in nations: A research synthesis. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 13(2), 435–456.

Aristotle. n.d. Politics. http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/politics.html.

Brown, G. K., Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Grisham, J. R. (2000). Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 371–377.

Christensen, H., Batterham, P. J., Soubelet, A., & Mackinnon, A. J. (2013). A test of the interpersonal theory of suicide in a large community-based cohort. Journal of Affective Disorders, 144, 225–234.

DeVries, M. W. (2007). Trauma in cultural perspective. In B. A. van der Kolk, A. C. Farlane, & L. Weisaeth (Eds.), Traumatic stress: The effects of overhelming experience on mind, body ans society (pp. 398–413). New York: The Guilford Press.

Diener, E. (1994). Assessing subjective well-being: Progress and opportunities. Social Indicators Research, 31, 103–157.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55, 34–43.

Diener, E. (2003). What is positive about positive psychology: The curmudgeon and Pollyanna. Psychological Inquiry, 14, 115–120.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13, 80–83.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5(1), 1–31.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The life satisfaction scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 403–425.

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97, 143–156.

Durkheim, E., Spaulding, J. A., & Simpson, G. (2010). Suicide. New York: Free Press.

Eckhaus, E., & Sheaffer, Z. (2018). Happiness enrichment and sustainable happiness. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9641-0.

Estes, R. J., & Sirgy, M. J. (2019). Global advances in quality of life and well-being: Past, present, and future. Social Indicators Research, 141(3), 1137–1164.

Forgas, J. P. (2006). Affective influences on interpersonal behavior: Towards understanding the role of affect in everyday interactions. In J. P. Forgas (Ed.), Affect in social thinking and behavior (pp. 269–290). New York: Psychology Press.

Frisch, M. B. (2006). Quality of life therapy: Applying a life satisfaction approach to positive psychology and cognitive therapy. New York: Wiley.

Graham, C. (2011). The pursuit of happiness: An economy of well-being. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Hayborn, D. M. (2008). The pursuit of unhappiness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Joshanloo, M. (2019). Investigating the relationships between subjective well-being and psychological well-being over two decades. Emotion, 19(1), 183–187.

Kahneman, D., Diener, E., & Schwarz, N. (Eds.). (1999). Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Kelloway, E. K., Weigand, H., McKee, M. C., & Das, H. (2013). Positive leadership and employee well-being. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 20(1), 107–117.

Maltseva, O. (2012). Assimilation of holiday and celebratory laughter in space of daily occurrence: Reasons, mechanisms, and consequences of the phenomenon. Skhid, 4(118), 144–149. https://doi.org/10.21847/1728-9343.2012.4(118).16574.

Maltseva, O. (2014). Laughter as a factor in the development of national socio-cultural identity of Ukrainian Cossacks. Skhid, 5(131), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.21847/1728-9343.2014.5(131).29625.

Maltseva, O. (2018). Simulation of laughter: The experience of reconstruction. Skhid, 3(155), 34–40. https://doi.org/10.21847/1728-9343.2018.3(155).139403.

Myers, D. G., & Diener, E. (2018). The scientific pursuit of happiness. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(2), 218–225.

Nagimzhanova, K. M., Baimanova, L., Magavin, S. S., Adzhibaeva, B. Z., & Betkenova, M. S. (2019). Basis of psychological and professional personality development of future educational psychologists. Periodico Tche Quimica, 16(33), 351–368.

Quick, J. C., Quick, J. D., Nelson, D. L., & Hurrell Jr., J. J. (1997). Individual consequences of stress. In J. C. Quick, J. D. Quick, D. L. Nelson, & J. J. Hurrell Jr. (Eds.), Preventive stress management in organizations (pp. 65–88). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10238-004.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78.

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. (1996). Psychological well-being: Meaning, measurement, and implications for psychotherapy research. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 65, 14–23.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York: The Free Press.

Seligman, M. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Free Press.

Sirgy, M. J. (2012). The psychology of quality of life. Cham: Springer Netherlands.

Sirgy, M. J., & Wu, J. (2009). The pleasant life, the engaged life, and the meaningful life: What about the balanced life? Journal of Happiness Studies, 10, 183–196.

Syrén, S. M., Kokko, K., Pulkkinen, L., & Pehkonen, J. (2019). Income and mental well-being: Personality traits as moderators. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00076-z.

Van Tongeren, D. R., & Burnette, J. L. (2018). Do you believe happiness can change? An investigation of the relationship between happiness mindsets, well-being, and satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(2), 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1257050.

Vaskeliene, I. (2012). Politinių represijų Lietuvoje ilgalaikės psichologinės pasekmės antrajai kartai. Vilnius: Vilniaus Universitetas.

Veenhoven, R. (2003). Hedonism and happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 4, 437–457.

Veenhoven, R. (2014). Happiness in Lithuania, world database of happiness. Erasmus University Rotterdam. http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl.

Walsh, L. C., Boehm, J. K., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2018). Does happiness promote career success? Revisiting the evidence. Journal of Career Assessment, 26(2), 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072717751441.

Warburton, D. (1996). The functions of pleasure. In D. Warburton & N. Sherwood (Eds.), Pleasure and quality of life. Chichester: Wiley.

Wong, N., Gong, X., & Fung, H. H. (2019). Does valuing happiness enhance subjective well-being? The age-differential effect of interdependence. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-00068-5.

World Health Organisation. n.d. https://www.who.int/about.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical Approval Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article has been retracted. Please see the retraction notice for more detail: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04913-6

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Patapas, A., Diržytė, A. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Happiness and satisfaction with life of Lithuanian residents after transition. Curr Psychol 41, 2445–2456 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00752-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00752-x