Abstract

Freedom is highly valued, but there are limits to the amount of freedom a society can allow its members. This begs the question of how much freedom is too much. The answers to that question differ across political cultures and are typically based on ideological argumentation. In this paper, we consider the compatibility of freedom and happiness in nations by taking stock of the research findings on that matter, gathered in the World Database of Happiness. We find that freedom and happiness are positively correlated in contemporary nations. The pattern of correlation differs somewhat across cultures and aspects of freedom. We found no pattern of declining happiness returns, which suggests that freedom has not passed its maximum in the freest countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Freedom ranks high among political values, next to goals such national safety, economic development and justice. The term freedom is frequently used in national constitutions and international treaties and figures in the names of political parties all over the world.

Worth of Freedom

This preference for freedom has been justified in two ways: by its own worth and by its consequences for other things we value. In that latter line of legitimation, freedom has been linked to happiness; one of the reasons for the political pursuit of freedom is the belief that this will add to greater happiness for a greater number of citizens. The common-sense theory behind this belief is that life will be more satisfying if we can live the way we want. Scientific theories have proposed an innate need for freedom. Deci and Ryan (1991) see ‘autonomy’ as one of three primary psychological needs of people, alongside ‘competence’ and ‘relatedness’. Likewise Welzel (2013) suggests that a preference for ‘emancipative values’ are innate, but exhibit themselves differently in accordance with existential pressures. People have greater flexibility in directing their actions towards outcomes they desire after their basic needs have been met, and not before (Welzel 2013).

Limits to Freedom

Still, it is also widely acknowledged that there are limits to freedom; there are limits to the freedom that a society can allow to its members and there are limits to the freedom that individuals can handle. One of the reasons for social limits to freedom is in requirements for functioning of the system; our modern society requires that people pay tax and stop at traffic lights. Another reason is that the freedom of one person may go at the cost of the freedom of another; that is why it is forbidden to enter someone else’s house without permission. Still another limit is in the side effects of freedom, too much freedom could create an individualistic society, where people feel isolated, anxious, and powerless (Fromm 1994). Individual limits to freedom are first of all in the ability to choose; that is why people who are deemed unable to make choices, such as children, are not allowed much freedom in their best interests. Another reason is in the ‘paradox of choice’; the notion that availability of too many choices causes anxiety and stress, and reduces one’s level of well-being (Schwartz 2009).

Research Questions

Given both the gains and costs of freedom, in this paper we aim to analyze the relationship between country-level freedom and average happiness in nations, subsequently referred to as ‘freedom’ and ‘happiness’. We address this question by examining the effect of different grades of freedom in nations on the happiness of people who live there. If freedom is positively associated with happiness, it would imply that the gains from freedom exceed the costs of freedom. On the other hand, if freedom is negatively associated with happiness, it means that the costs of freedom exceeds its gains. Our intuition is that freedom is positively associated with happiness. Indeed, the World Happiness Report presents perceived freedom to make life choices as one of the six determinants of national-level happiness, measured by the Cantril ladder (Helliwell et al. 2017).Footnote 1 Yet we acknowledge that more is not always better and that there can be too much freedom in a country. So, we also determine the existence of a possible turning point in the relationship between freedom and happiness; do high levels of freedom incur diminishing returns, in terms of happiness? In short, we seek an answer to the following questions:

-

1.

Does greater freedom in nations go with higher happiness?

-

2.

What kind of freedom is the most conducive for happiness?

-

3.

Under what conditions does freedom contribute to happiness?

-

4.

Is there a turning point beyond which more freedom does not add to greater happiness?

In answering these questions, we utilize existing studies on the relationship between freedom and happiness, effectively creating a research synthesis. Findings from the existing studies are accessed from the ‘World Database of Happiness (WDH)’ (Veenhoven 2017), a source which is discussed in more detail in “Data Source: the World Database of Happiness” section of this paper.

The paper is organized as follows. We start with a delineation of the concepts and a subsequent selection of measures. Next, we consider the concepts of freedom and happiness, as well as their measures. We then present the available data on freedom and happiness in nations. On that basis, we answer our research questions. Finally, we conclude.

Freedom

Notions of Freedom

Freedom is defined as the possibility to choose. A person can be said to be free if his or her condition allows for choice, and if that choice is not inhibited by others. Since choice is always limited, we deal in fact with the degree to which choice is possible. Most of the literature on freedom is about the factual possibility to choose; we call that ‘actual’ freedom. Next, there is a research literature about the subjective stance to that phenomenon, which we call ‘attitudes to freedom’.

Actual Freedom

The actual possibility to choose depends on: (1) the opportunity to choose, and (2) the capability to choose (Veenhoven 2000).

Opportunity to Choose

The opportunity to choose is the extent to which one’s social environment enables or inhibits choice. More specifically, for the opportunity to choose to exist, there has to be an availability of choices (options), and the absence of inhibition to choose by others.

The availability of choice is dependent on lifestyle alternatives that are present in society, which differs by current mode of existence. For example, simple hunter-gatherer societies provide their members with a more limited assortment than highly differentiated industrial societies. Variety also depends on internal dynamics and contact with foreign cultures. The availability of choices in a society is affected by things like material affluence, division of work, and cultural variety (Veenhoven 2000). This aspect of freedom cannot be well quantified and will therefore not be considered in this paper.

When there is an availability of choices, opportunity to choose then depends on the absence of inhibition by others, in terms of restrictive laws or oppression from authority figures. This kind of freedom is considered in this paper. Specifically, we look at economic freedom, political freedom, and personal freedom.

Capability to Choose

The opportunity to choose only translates into freedom if the opportunity is seized. Seizing an environmental opportunity requires inner capacity to choose, which involves an awareness of alternatives, as well as an inclination to choose.

An awareness of alternatives is dependent on what one knows; one can only make a choice if one is aware of the availability of choice options. The lack of awareness of available choices is akin to not having choices. What a person knows is then dependent on education, as well as the information that he or she is privy to.

Next to the awareness of alternatives, the capability to choose requires an inclination to act. This requires inner strengths; you may see the options, but lack the guts to choose. This proclivity to choose depends on many things, among which prevailing norms in society. In a society characterised by individualist, rather than collectivist norms, people are more likely to make choices that are consistent with their own desires, rather than conforming to group interests.

These different kinds of freedom can be illustrated using the example of a prisoner. When the door of the prison is locked, the prisoner has no opportunity to choose whether to flee or not. Yet suppose the guards are on leave and forgot to lock the door. In that case, there is an opportunity to choose, but that opportunity can be used only if the prisoner is aware of this alternative. Using the same example to describe the inclination to choose, prisoners who see the open door may let the opportunity pass, not having the courage to seize the opportunity, even if they would like to leave the prison. This inclination may also depend on moral conviction and reality beliefs. Choice, and making decisions, involves a degree of uncertainty and responsibility, which people may not be willing to undertake.

Attitudes to Freedom

Next to the above variants of ‘actual’ freedom, there are various ‘attitudes’ to freedom. An ‘attitude’ to something is a combination of beliefs, evaluations and action tendencies. The following attitudinal phenomena figure in the research literature on freedom:

Perceived Freedom

This is the degree to which one thinks to be in control of one’s situation. Perceived freedom can differ from actual freedom; one may think one is free, while one is not, or have much opportunity to choose, but think that one is being controlled by others. In psychology this matter is often referred to as ‘control belief’, or ‘locus of control’ (Rotter 1990).

Satisfaction with Freedom

Perceptions of the degree of freedom in a nation tend to go together with evaluations of the situation. Satisfaction with freedom does not always concur with actual freedom; one can be fairly free, but want more, or be unfree and content.

Valuation of Freedom

Another attitude towards freedom is how desirable freedom is deemed to be. Though freedom ranks high in the value hierarchy of most people, not everybody values freedom equally much. Next to individual differences in the appreciation of freedom within nations there are considerable differences in valuation of freedom across nations; freedom being valued higher in contemporary Western nations than in Eastern Asia (Welzel and Inglehart 2010).

There is some conceptual overlap between these attitudes to freedom and the notions of ‘capability to choose’ discussed in “Actual Freedom” section. ‘Perceived freedom’ is close ‘awareness of alternatives’, though the global estimate of opportunity may differ from the awareness of particular alternatives. It is also possible that one thinks to be free, because one is unaware of restrictions, or that one thinks to be restricted while failing to see opportunities to choose.

Likewise there is overlap between ‘valuation of freedom’ and the ‘inclination to choose’; if you despise freedom, you will be less inclined to go your own way. Yet it is also possible that you look down on freedom, but still do what you want, or that you praise freedom, but conform.

An overview of these notions of freedom is presented on Fig. 1. The conceptual overlap between capability to choose and attitudes to freedom is visualized by partly overlapping boxes. Note that for the opportunity to choose and capability to choose, the first condition is necessary before meeting the second, i.e. the availability of choices is necessary in determining the opportunity to choose, before the lack of inhibition affects the opportunity. Similarly, an awareness of alternatives is necessary before the inclination to choose affects the capability to choose. This has been described in full in “Actual Freedom” section above.

Measures of Freedom in Nations

The answering of our research questions requires that we measure freedom in nations. Below we review the measures used for that purpose. We start with measures of ‘actual’ freedom and next review current measures of ‘attitudes’ to freedom in the nation. An overview of these measures is presented in Table 1.

Above in “Notions of Freedom” section we clearly defined different aspects of freedom. The measures used in empirical research on freedom do not always fit these conceptual distinctions. For example, one of the measures of political freedom is the index of political rights and civil liberties by Freedom House (2016). Close reading of the items in the index reveals that while the ‘political rights’ portion of the index is consistent with our definition of political freedom, the ‘civil liberties’ portion of the index is conceptually more similar to the concept of personal freedom.Footnote 2 Since our study is a research synthesis, we are constrained by the methodology of existing empirical studies, which typically use the index as a whole in order to measure the relationship between political freedom and happiness (e.g. Veenhoven 1999; Elliott and Hayward 2009; Bjørnskov et al. 2010).

At this juncture, it is important to acknowledge that there is empirical evidence in the literature that demand for the different types of freedom in a country is likely to occur simultaneously. In their conception of the human development syndrome, Welzel et al. (2003) propose that human development is “shaped by a process in which socioeconomic development and rising emancipative mass values lead to rising levels of effective democracy; and that the effect of emancipative values on effective democracy operates through their impact on elite integrity.” To be specific, emancipative values refer to the values that are related to the desire of an existence free from domination (Welzel 2013, 2). In a series of publications, the authors find evidence that socioeconomic development leads to a rise in values that emphasise freedom and autonomy; values which then become drivers for improvement of the institutions of a country in the form of effective democracy (Welzel et al. 2003; Welzel and Inglehart 2010). Effective democracy refers to the extent to which formally institutionalised civil and political rights are effective in practice (Inglehart and Welzel 2005). Given that effective democracy is measured by the Freedom House index of political rights and civil liberties, which, in this study, is used as a measure of political freedom, and also encompasses personal freedom, an implication of this finding is that the different aspects of freedom delineated in “Notions of Freedom” section are likely to be endogenous.

In a later publication, Welzel (2013) makes the same proposition, with the additional conjecture that emancipative values are innate for every individual, and either remain dormant or are developed depending on existential pressures, that is, the degree to which basic needs are met.Footnote 3 Subsequently, if the majority of the public places a high level of emphasis on emancipative values, they are more likely to demand for institutional changes that are consistent with these values. In the context of the notions of freedom, as measured in Table 1, a decline in existential pressures associated with socioeconomic development is typically characterised by higher levels of education and information, increasing the level of awareness of alternatives. An increasing emphasis on emancipative values weakens vertical authority relations and strengthens horizontal bargaining relations (Welzel et al. 2003), thus decreasing the level of power distance, and increasing the level of individualism in a society. This results in a greater inclination to choose. Further, if the demand for institutional change in accordance to the level of emancipative values in a society is effective, it will result in higher levels of economic, political, and personal freedom, or opportunity to choose. Finally, the objective increases in the levels of freedom is likely to have an effect on attitudes towards freedom. The description of this process shows that although the concept of freedom can be delineated into different types of freedom, it is ultimately an umbrella term for related concepts that do not exist in isolation and occur endogenously.

Happiness

Concept of Happiness

The word ‘happiness’ has been used for different meanings; sometimes for denoting the objective quality of life and sometimes for the subjective appreciation of it. In present day Happiness Economics, the word is used in the latter sense and defined as the ‘subjective enjoyment of one’s life as a whole, that is, as ‘life satisfaction’. This concept is delineated in more detail in (Veenhoven 1984: Ch. 2).

Measures of Happiness

Thus defined, happiness is something that people have on their mind and therefore happiness can be measured using questioning. Different questioning techniques are being used, direct as well as indirect questioning and single questions or multiple item questionnaires. A commonly used single direct question reads as follows:

Taking everything together, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you currently with your life as a whole?

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

Dissatisfied | Satisfied |

Validity

Though these questions are fairly clear, responses can be flawed in several ways. Responses may reflect how happy people think they should be rather than how happy they actually feel and it is also possible that people present themselves as happier than they actually are. These suspicions have given rise to numerous validation studies. A review of these qualms provided no evidence that responses to these questions measure something other than what they are meant to measure (Veenhoven 1984: Ch. 3). Though this is no guarantee that research will never reveal a deficiency, we can trust these measures of happiness for the time being.

Reliability

Research has also shown that responses are affected by minor variations in wording and ordering of questions and by situational factors, such as the race of the interviewer or the weather. As a result, the same person may score 6 in one investigation and 7 in another. This lack of precision hampers analyses at the individual level. It is less of a problem when average happiness in nations is compared, since random fluctuations tend to balance in big samples.

Comparability

Still, the objection is made that responses on such questions are not comparable, because a score of 6 does not mean the same for everybody. A common philosophical argument for this position is that happiness depends on the realization of wants and that these wants differ across persons and cultures (Smart and Williams 1973). Yet, it is not at all sure that happiness depends very much on the realization of idiosyncratic wants. The available data are more in line with the theory that happiness depends on the gratification of universal needs (Veenhoven 1991, 2009), and there is also much similarity in aspirations across contemporary nations.

A second qualm is whether happiness is a typical Western concept that is not recognized in other cultures. Happiness appears to be a universal emotion that is recognized in facial expression all over the world (Ekman and Friesen 1976) and for which words exists in all languages. The question on life-satisfaction is well understood all over the world, the share of respondents who tick the ‘don’t know’ option is typically less than 1% (Veenhoven 2010).

A related objection is that happiness is a unique experience that cannot be communicated on an equivalent scale. Yet from an evolutionary point of view, it is unlikely that we differ very much. As in the case of pain, there will be a common human spectrum of affective experience. If happiness were a wholly idiosyncratic phenomenon, survey research would not find the correlations it does find.

Last, there is methodological reservation about possible cultural-bias in the measurement of happiness, due to problems with translation of keywords and cultural variation in response tendencies. Though there is evidence for some of these distortions the net effects seems to be small. Veenhoven (2012) estimates that only some 5% of the observed cross-national differences in happiness is due to cultural measurement bias.

Collection of Acceptable Measures

Though happiness appears to be well measurable, not all measures ever used measure the concept equally well. Some questionnaires that claim to measure happiness actually tap slightly different things, for example the often used General Wellbeing Questionnaire measures ‘mental health’ and not ‘happiness’ as defined here. This appears from close reading of the questions used. All measures that fit the concept of happiness as defined above are gathered in the collection of Happiness Measures, which is part of the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 2017).

Freedom and Happiness in Nations

Based on our definitions of freedom and happiness in “Freedom” and “Happiness” sections, we set out to answer our four research questions by utilizing existing research findings on the association between the phenomena at the macro level of nations. The analyses utilized in order to obtain these results are primarily cross-sectional, or pooled repeated cross-sections. These findings are presented in Table 2.

Data Source: The World Database of Happiness

We draw on research findings gathered in the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 2017). The World Database of Happiness is an archive of research findings on the subjective enjoyment of life. It brings together findings that are scattered throughout many studies and provides a basis for research synthesis. The focus of this ‘findings archive’ is on happiness in the sense of “the subjective enjoyment of one’s life as a whole”. The archive is available at the internet at https://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl

Building blocks of this database are electronic ‘finding pages’, which involve a description of a research findings on happiness, using a standard terminology and format. Finding pages provide information on (1) the publication in which this result was reported, (2) the population in which this result was observed, (3) the method with which the result was obtained, (4) the observed distribution of happiness in that population and (5) the observed co-variates of happiness. Finding pages are ‘dynamic’, that is, they are made-up instantly in response to a request from different collections in the data system. To date, the database includes some 25.000 such finding pages. An example of such a page is presented in Fig. 3 in Appendix 3. Finding pages can be sorted in many ways, such as by co-variate subject, statistical analysis and population studies.

Finding pages are gathered in ‘collections’, one of which is the ‘Collection of Correlational Findings’. Research findings in that collection are sorted by subject, and one of the subject categories is section N04: Happiness and Condition in One’s Nation. A subsection is about Freedom and Happiness in nations (N04a0) and we use the findings gathered in that subsection to answer the questions mentioned above. We assessed that collection January 2016. At that time, the collection involved 101 findings on this subject. All these findings are based on cross-sectional analysis of happiness and freedom in nations at a particular point in time. As yet, trend studies on this topic are not available.

Presentation of the Findings

This review follows a format introduced by Veenhoven (2015). Instead of providing lengthy discussions of the research findings in the subject area, we take advantage of the online availability of standardized description in the World Database of Happiness, by providing links to the findings pages.

All the observed relationships between freedom and happiness are reported in this review, irrespective of their magnitude. Positive associations are indicated with a plus sign (+), while negative associations are indicated with a minus sign (−). Statistically significant associations at the 5% level are indicated by bolded plus and minus signs (+ and - respectively). Several signs in a string, such as −/−/+/+ indicate different findings obtained in the same study, typically due to variations in analysis. The signs involve links to the World Database of Happiness. Using ‘Control + Click’ brings the reader to ‘finding pages’ where the research finding is described in detail.

This format allows us to make statements about main trends in the data without burdening the reader with all the detail, while also making our analysis controllable. Among other advantages of this format is the possibility of making our review comprehensive, containing all known research findings, instead of being selective. Further, our review enables the interested reader to easily access more complete descriptions of the findings on the World Database of Happiness. Another advantage of using the World Database of Happiness as the source for this review is its conceptual specificity. As previously mentioned, the Database limits its scope to studies that define happiness as the subjective enjoyment of life as a whole, thus making our review more precise. This format also enables us to easily identify areas in which there is still room for research, based on the lack of research findings.

Results

To reiterate, by synthesizing research findings from past studies documented in the World Database of Happiness, we first consider whether freedom is associated with greater happiness (Question 1). We then try to identify whether certain types of freedom are more important than others, and subsequently, the type of freedom that is most conducive for happiness (Question 2). We also try to determine the conditions under which freedom contributes to happiness (Question 3). Finally, we attempt to identify whether there is diminishing utility of freedom in the countries that have high levels of freedom, indicating that there is too much freedom (Question 4).

Is Freedom Associated with Greater Happiness?

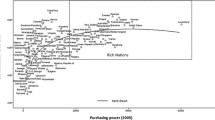

Table 2 shows that there is evidence in the research literature of a positive association between freedom and happiness. This is especially true if we only consider findings that are statistically significant at the 5% level. When there exists statistically significant relationship between each type of freedom and happiness, the relationship is a lot more likely to be positive rather than negative. This positive relationship is also illustrated in Fig. 2.Footnote 4

There is, however, the possibility of spurious correlation between freedom and happiness, as a result of omitted variable bias. The more variables controlled for in an analysis, the lower the probability of omitted variable bias. In the third column of Table 2, where the partial correlations between freedom and happiness are reported, among the variables commonly controlled for is GDP per capita (Veenhoven 2000; Tsai 2009; Rode 2012; Bjørnskov 2014). Some studies control for a multitude of factors. For example, Gehring (2013) controls for social trust, belief in God, investment price level, log GDP per capita, government share as a percentage of GDP, as well as regional and period dummies. Hence, we can be more certain that the positive relationship between economic freedom and happiness found by Gehring (2013) is not spurious.Footnote 5 This, however, is associated with other limitations which are discussed further in “Discussion” section below.

What Kind of Freedom is the Most Conducive for Happiness?

Table 2 also provides us with the opportunity to identify exactly which types of freedom are more conducive for happiness than others. We find that of all the types of freedom, economic freedom is the most consistent in establishing a significant positive relationship with freedom. This is also true, for the most part, for political freedom.

In general, the other types of freedom that have been studied in the literature, have also been found to have positive relationships with happiness, as described in Section 4.3.1 above. However, the low number of studies that explored these relationships presses for caution. There is need for more research in this area.

Under What Conditions Does Freedom Contribute to Happiness?

In Table 3, we tabulate the findings on the relationship between freedom and happiness by the wealth of nations. It should be noted that the distinction between wealthy and poor nations is arbitrary, dependent on the discretion of the author(s) of each publication.Footnote 6 We believe that the differences in the distinction does not prove to be a problem, as the method of distinction by each of the authors is sound.

Overall, we find that the positive relationship between economic freedom and happiness is stronger for poor nations relative to wealthy nations. This indicates that economic freedom only substantially improves subjective well-being for developing nations. In developed nations, which are usually characterized by high levels of economic freedom, more economic freedom adds little to average happiness. For political freedom, and the lack of inhibition in general, there is evidence of a positive relationship between freedom and happiness in wealthy nations, which is not fully reflected in poor nations. However, it should be noted that only a limited number of studies have separated poor and wealthy nations in their analyses, restraining our ability to ascertain a moderating effect of wealth on the association between freedom and happiness.

Aside from the wealth of nations, in his macro study of 79 countries, Gehring (2013) analyses the relationship between economic freedom and happiness for different socio-economic groups. Specifically, he conducts separate analyses for people who are younger and people who are older than the median age in their respective countries, men and women, people from low and high social classes, as well as people with left and right political orientations. He finds that these socio-economic categories do not seem to affect the significant positive relationship between economic freedom and happiness found in the overall sample, yielding coefficients and standards errors that are highly similar.Footnote 7 However, Elliott and Hayward (2009), who find that an index of civil, religious, and political freedom is negatively associated with happiness, also find that an increase in religiosity, based on religious attendance and declaration of oneself as a religious person, increases the negative effect of freedom on happiness.

Is there Too Much Freedom in the Freest Countries?

Our last research question is whether freedom has passed its optimum in the most free nations of the present day world. In order to determine whether there exists a pattern of diminishing returns to freedom, we look at the moderating effect of freedom on the relationship between freedom and happiness. If freedom is positively associated with happiness at high levels of freedom, it would imply that there are no diminishing returns to freedom. The relationships between the different types of freedom and happiness, categorized by the existing level of freedom in the country is illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4 shows that at low levels of freedom, the relationship between freedom and happiness is mixed; some measures are negatively associated with happiness, while other measures have positive associations. However, only some of the positive associations are statistically significant. The negative associations, and two of the positive associations are not statistically significant. On the other hand, at high levels of freedom, there is evidence of a positive relationship between freedom and happiness. In the relevant studies, almost every type of freedom has been found to have a significant positive association with happiness at high levels of freedom, with the exception of the inclination to choose, which is also found to have a positive association with happiness, although the effect is not significant.

Overall, these findings show that even among the countries with the highest levels of freedom, the level of freedom is still not too high, as freedom still has a positive association with happiness. This indicates that the freest countries are not (yet) too free from a happiness perspective. This point is further illustrated in Fig. 2, where the scatterplots between economic freedom and perceived freedom with happiness reflect upward trends.

Discussion

In this study, we seek to understand the relationship between freedom and happiness is nations, mainly by utilizing existing findings on this subject, recorded in the World Database of Happiness. Given this approach, we are limited by the approaches and measures that have been used by other researchers. Nevertheless, this paper is a good starting point in understanding the relationship between freedom and happiness across countries, and provides the reader with insight on existing studies on the subject matter. It also highlights the potential of the World Database of Happiness in advancing research. While these results provide much insight on the relationship between freedom and happiness in nations, they also raise a few important questions, especially about the methodological rigor of the studies included in this synthesis.

Reverse Causality?

The first question is to what extent the positive relationship between freedom and happiness is driven by an effect of happiness on freedom, that is, is by reverse causality. In the case of actual freedom, the possibility of reverse causality is not self-evident, but still possible. Happy electorates can be more open for freedom. In their model of human development, Ronald Inglehart and Christian Welzel of the World Values Survey argue and present evidence that the sequence of human development begins with socioeconomic development, which induces a change towards emancipative values, and subsequently the demand for institutional reforms that are consistent with emancipative values (Inglehart and Welzel 2005; Welzel 2013). Fulfillment of these demands lead to higher levels of life satisfaction (Welzel 2013). However, other scholars have presented theoretical arguments for a different sequence of these events associated with human development (see Welzel et al. 2003). For example, scholars have argued that causality runs from democracy to the rise of social capital and civic values (Rustow 1970; Muller and Seligson 1994; Jackman and Miller 1998). These values include trust, which is one of the components that allows for horizontal bargaining relations (as opposed to vertical authority relations) and thus emancipative values.

In the case of attitudes towards freedom, reverse causality is also possible. Happiness is likely to foster a generally positive outlook, which may be reflected by higher levels of perceived freedom and satisfaction with freedom.

Spurious Correlation?

A second question is to what extent the observed correlations between freedom and happiness in nations are driven by effect of other variables on both, such as economic prosperity which adds both to happiness and freedom. Several of the studies in our analysis have dealt with that problem using regression analysis with various control variables, such as GDP per capita, the unemployment rate, and regional dummies. Such analyses typically reduce the effect size, but still leave a positive correlation (cf Table 2, third column).

Whatever the results may be, this approach has important limitations and is for that reason not pursued in this paper. One limitation is that one cannot control all possible intervening variables, both because of data shortage and because of the limited number of cases in this nation level analysis. A second limitation is that this medicine is typically worse than the disease when applied on highly interrelated variables, such as in this case of country characteristics. For instance, control for economic prosperity wipes away probable indirect effects of freedom on happiness though wealth. The available cross-sectional data do not allow a good answer to this question. Analysis of long-term trends that become available in the future may shed more light on this issue.

Why is There Not Too Much Freedom?

As noted in the introduction there are claims that freedom has passed its maximum in developed societies. Yet we did not find any evidence for that view. Why not? One possibility is that in the freest nations, the capability to choose has also increased in tandem. There is evidence that people have become more educated, and cultures have also become more individualistic (Inglehart and Welzel 2005; Welzel 2013), giving them the ability to cope with increasing freedom. As a result, the high levels of freedom have not adversely affected people’s subjective well-being.

Research Agenda

Finally, what do we not know about the relationship between freedom and happiness in nations? One of the advantages of the technique that we have used in this research synthesis is that we can easily identify the current gaps in the literature based on the empty sections in Table 2. Table 2 shows that there is an obvious gap in research on the relationship between attitudes towards freedom and happiness, with no current research available on the relationship between the valuation of freedom and happiness. Further, we also find that there is limited empirical evidence on the relationship between personal freedom and happiness, as well as the relationship between combined measurements of freedom and happiness. These gaps provide avenues for further research.

Still another white spot is cross-temporal research. In the World Database of Happiness, we did not find any analyses of correspondence between changes in freedom in nations with changes in the happiness of citizens. Though such analyses have been made with economic growth or decline (e.g. Veenhoven and Vergunst 2014), they have not yet been made for growth or decline in freedom.

Conclusions

Using the research findings archived in the World Database of Happiness, we find that the relationship between freedom and happiness in nations is predominantly positive. We find some evidence that poor nations benefit more from an increase in economic freedom, compared to wealthy nations. The positive relationship between freedom and happiness appear to persist even in nations with high levels of existing freedom, indicating freedom has not reached its maximum, from a happiness perspective.

Change history

29 August 2017

An erratum to this article has been published.

Notes

The six determinants are GDP per capita, social support, healthy life expectancy, generosity, freedom from corruption, and freedom to make life choices. Together, these six variables explain 74% of the variation (adjusted R-squared) in the national annual average ladder scores of countries (Helliwell et al. 2017).

A full description of the construction of the index is available at: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world-2016/methodology

This proposition, as well as the one in the previous paragraph are not new, and are built on past theories and literature that are not within the scope of our study. The publications by Inglehart, Welzel, and Klingemann are the most relevant to our study as they also provide empirical evidence of the human development syndrome. A detailed theoretical background is available in Welzel et al. (2003) and Welzel (2013).

The happiness measure used is the average response to the Cantril ladder question, which asks respondents to rate their quality of life on a scale of 0 to 10, with higher values meaning higher levels of happiness. It is the average response for the years 2013–2015, obtained from the World Happiness Report 2016 (Helliwell et al. 2016). The measure of economic freedom is on a scale from 1 to 10, where higher values indicate higher levels of economic freedom, obtained from the Economic Freedom of the World Report 2015 (Gwartney et al. 2015). The measure of perceived freedom is on a scale of 1 to 10, with higher values meaning higher levels of perceived freedom. It is obtained from the sixth wave of the World Values Survey, conducted in the years 2012–2014, and is described in detail in Section 2.3 above.

The link to the WDH finding page for the relationship between economic freedom and happiness in Gehring (2013) is: http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl/hap_cor/desc_cor.php?sssid=24018

This distinction is stated in the page that lists the research findings on the World Database of Happiness, accessible from the table by Control + Click on the symbols representing each association.

Findings in the World Database of Happiness: http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl/hap_cor/desc_cor.php?sssid=24018

References

Bjørnskov, C. (2014). Do economic reforms alleviate subjective well-being losses of economic crises? Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(1), 163–182. doi:10.1007/s10902-013-9442-y.

Bjørnskov, C., Dreher, A., & Fischer, J. A. V. (2007). The bigger the better? Evidence of the effect of government size on life satisfaction around the world. Public Choice, 130(3–4), 267–292. doi:10.1007/s11127-006-9081-5.

Bjørnskov, C., Dreher, A., & Fischer, J. A. V. (2010). Formal institutions and subjective well-being: revisiting the cross-country evidence. European Journal of Political Economy, 26(4), 419–430. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2010.03.001.

Cheibub, J. A., Gandhi, J., & Vreeland, J. R. (2009). Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice, 143(1–2), 67–101. doi:10.1007/s11127-009-9491-2.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). A motivational approach to self: integration in personality. In R. A. Dienstbier (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation 1990 (Vol. 38, pp. 237–288). Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1976). Pictures of facial affect. California: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Elliott, M., & Hayward, R. D. (2009). Religion and life satisfaction worldwide: the role of government regulation*. Sociology of Religion, 70(3), 285–310. doi:10.1093/socrel/srp028.

Freedom House (2016). Freedom in the World 2016. Retrieved from www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2016.

Frijters, P., Haisken-DeNew, J. P., & Shields, M. A. (2004). Investigating the patterns and determinants of life satisfaction in Germany following reunification. The Journal of Human Resources, 39(3), 649–674. doi:10.2307/3558991.

Fromm, E. (1994). Escape from Freedom (Reprint). New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Gehring, K. (2013). Who benefits from economic freedom? Unraveling the effect of economic freedom on subjective well-being. World Development, 50, 74–90. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.05.003.

Gerring, J., Bond, P., Barndt, W. T., & Moreno, C. (2005). Democracy and economic growth: a historical perspective. World Politics, 57(3), 323–364.

Gwartney, J. D., Lawson, R., & Hall, J. (2015). Economic Freedom of the World: 2015 Annual Report. Fraser Institute. Retrieved from www.fraserinstitute.org.

Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. (2016). World Happiness Report 2016, Update (Vol. I). New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. (2017). World Happiness Report 2017. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Henisz, W. J. (2000). The institutional environment for economic growth. Economics and Politics, 12(1), 1–31. doi:10.1111/1468-0343.00066.

Henisz, W. J. (2002). The institutional environment for infrastructure investment. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11(2), 355–389. doi:10.1093/icc/11.2.355.

Heston, A., Summers, R., & Aten, B. (2002). Penn World Table Version 6.1. Center for International Comparisons at the University of Pennsylvania (CICUP).

Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverly Hills: SAGE.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Humana, C. (1992). World human rights guide. New York: Oxford University Press.

Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, cultural change, and democracy: the human development sequence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jackman, R. W., & Miller, R. A. (1998). Social capital and Politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 1(1), 47–73. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.1.1.47.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2010). The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 1682130). Rochester: Social Science Research Network. Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1682130.

Miller, T., & Kim, A. (2016). 2016 Index of Economic Freedom. The Heritage Foundation and Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

Muller, E. N., & Seligson, M. A. (1994). Civic culture and democracy: the question of causal relationships. The American Political Science Review, 88(3), 635–652. doi:10.2307/2944800.

Rode, M. (2012). Do good institutions make citizens happy, or do happy citizens build better institutions? Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(5), 1479–1505. doi:10.1007/s10902-012-9391-x.

Rotter, J. B. (1990). Internal versus external control of reinforcement: a case history of a variable. American Psychologist, 45(4), 489–493. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.45.4.489.

Rustow, D. A. (1970). Transitions to democracy: toward a dynamic model. Comparative Politics, 2(3), 337–363. doi:10.2307/421307.

Schwartz, B. (2009). The paradox of choice. New York: Harper Collins.

Smart, J. J. C., & Williams, B. (1973). Utilitarianism: for and against. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tsai, M.-C. (2009). Market openness, transition economies and subjective Wellbeing. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(5), 523–539. doi:10.1007/s10902-008-9107-4.

Veenhoven, R. (1984). Conditions of happiness. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Veenhoven, R. (1991). Is happiness relative? Social Indicators Research, 24(1), 1–34. doi:10.1007/BF00292648.

Veenhoven, R. (1999). Quality-of-life in individualistic society. Social Indicators Research, 48(2), 159–188. doi:10.1023/A:1006923418502.

Veenhoven, R. (2000). Freedom and happiness: a comparative study in forty-four nations in the early 1990s. In E. Diener & E. M. Suh (Eds.), Culture and subjective well-being (pp. 257–288). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Veenhoven, R. (2009). How do we assess how happy we are? Tenets, implications and tenability of three theories. In A. K. Dutt & B. Radcliff (Eds.), Happiness, Economics and Politics: towards a multi-disciplinary approach (pp. 45–69). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Veenhoven, R. (2010). How universal is happiness? In E. Diener, D. Kahneman, & J. Helliwell (Eds.), International differences in well-being (pp. 328–350). New York: Oxford University Press.

Veenhoven, R. (2012). Cross-national differences in happiness: cultural measurement bias or effect of culture? International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(4). doi:10.5502/ijw.v2.i4.4.

Veenhoven, R. (2015). Informed pursuit of happiness: what we should know, do know and can get to know. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(4), 1035–1071. doi:10.1007/s10902-014-9560-1.

Veenhoven, R. (2017). World database of happiness: archive of research findings on subjective enjoyment of life. Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Retrieved from http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl.

Veenhoven, R., & Vergunst, F. (2014). The Easterlin illusion: economic growth does go with greater happiness. International Journal of Happiness and Development, 1(4), 311–343. doi:10.1504/IJHD.2014.066115.

Wacziarg, R., & Welch, K. H. (2008). Trade liberalization and growth: new evidence. The World Bank Economic Review, 22(2), 187–231. doi:10.1093/wber/lhn007.

Welzel, C. (2013). Freedom rising: human empowerment and the quest for emancipation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Welzel, C., & Inglehart, R. (2010). Agency, values, and well-being: a human development model. Social Indicators Research, 97(1), 43–63. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9557-z.

Welzel, C., Inglehart, R., & Klingemann, H.-D. (2003). The theory of human development: a cross-cultural analysis. European Journal of Political Research, 42(3), 341–379. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.00086.

World Bank. (2016). World development indicators 2016. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/datacatalog/world-development-indicators.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The original version of this article was revised: modifications have been made to Tables 2, 3, and 4, captions to Figs. 2 and 3, and hyperlinks to the findings pages on the World Database of Happiness in page 11. Full information regarding corrections made can be found in the erratum for this article.

Ruut Veenhoven is on the Editorial Policy Board of the Applied Research in Quality-of-Life journal, and one of the Board of Directors of the International Society of Quality-of-Life Studies.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abdur Rahman, A., Veenhoven, R. Freedom and Happiness in Nations: A Research Synthesis. Applied Research Quality Life 13, 435–456 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-017-9543-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-017-9543-6