Abstract

The current study investigated the interrelationships among parental attachment, gratitude, and life satisfaction during late adolescence, including the mediation effect of gratitude in the relationship between parental attachment and life satisfaction. Specifically, analyses have been conducted considering both paternal and maternal roles. A sample of two hundred and eighty-five college students participated and completed measures of paternal attachment, maternal attachment, gratitude, and life satisfaction. A cross-sectional design was conducted in the present study. The results showed statistically significant relationships among all study variables, and gratitude partially mediated the relationship between life satisfaction and attachment to one’s father and mother. The current work advances the understanding of the effects of parents of different gender on individuals’ development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Due to advancements in positive psychology, psychological research is increasingly focusing on the importance of life satisfaction (Proctor et al. 2009). Life satisfaction is a component of subjective well-being (Tov and Diener 2009) and a positive indicator of mental health (Steger et al. 2011). Substantial evidence suggests a protective mechanism of life satisfaction against the negative effects of stress and the development of psychological disorders (Proctor and Linley 2014). Moreover, while high levels of life satisfaction are associated with happiness and good living conditions (Diener et al. 2009), low levels of life satisfaction are associated with depression and unhappiness (Martikainen 2012).

Therefore, it is necessary to explore the factors that influence life satisfaction. Several variables have been identified as being associated with individuals’ life satisfaction (Huebner 2004; Proctor et al. 2009), such as environmental variables (e.g., life events, culture), demographic variables (e.g., age, socioeconomic status), intrapersonal variables (e.g., personality, character strength), and interpersonal variables (e.g., parental relationship, interaction with family). Notably, the latter two variables are stronger predictors than the former two variables.

Among the interpersonal variables, parental attachment has been shown to have a significant impact on individuals’ life satisfaction (Martikainen 2012). Studies show that individuals with secure attachments have higher life satisfaction (Chen et al. 2017; Guarnieri et al. 2015; Jiang et al. 2013; Kumar and Mattanah 2016; Pan et al. 2016). Likewise, gratitude, as an important interpersonal and intrapersonal variable, has an important effect on individuals’ life satisfaction, such that individuals’ with high levels of gratitude have higher life satisfaction (Chan 2011; Emmons and McCullough 2003; Park et al. 2004; Peterson et al. 2007; Watkins et al. 2003).

Although previous research has probed the influence of parental attachment and gratitude on life satisfaction, few researchers have simultaneously explored their possible effects on life satisfaction in adolescent samples. Moreover, few studies have specifically investigated the different effects of paternal and maternal attachment on individuals’ psychological development and health (e.g., gratitude, life satisfaction). In addition, the potential psychological mechanisms that underlie these variables have not been fully examined. Thus, this study examined the associations between parental attachment (i.e., paternal and maternal attachment), gratitude, and life satisfaction among Chinese young adults and further explored the potential psychological mechanisms that underlie them.

Attachment and Life Satisfaction

Attachment is a relational pattern that is formed during early childhood interactions with caregivers. The relational pattern not only reflects internal working models of oneself, others, and relationships (Bartholomew and Shaver 1998; Bowlby 1982) but also influences people’s interactions with others throughout their lives (Karen 1994; Lawler-Row et al. 2006). On the other hand, life satisfaction refers to the extent to which an individual feels satisfied with his or her overall life (Huebner 2004). Life satisfaction is defined as an individual’s global and subjective evaluation of his or her overall quality of life (Diener et al. 1999).

According to attachment theory, early secure attachment relationships with parents provide the foundation for the development of psychosocial adjustment throughout adolescence and into adulthood (Whittaker and Cornthwaite 2000). Similarly, the development of insecure patterns of attachment to parents has been associated with the development of maladaptive symptoms in childhood and with several indices of psychological distress through emerging adulthood (Greenberg et al. 1990).

As mentioned above, attachment reflects internal working models of oneself, others, and relationships (Bartholomew and Shaver 1998; Bowlby 1982). Securely attached individuals are more likely to develop generally positive internal working models (Bowlby 1988), which include positive thoughts about attachment figures, the self, the environment, and others as mental representations of individuals. In other words, individuals who have experienced consistently loving and supportive caregivers and have a secure basis for exploring the world will likely have a secure attachment style and regard others as trustworthy and responsive, enabling them to maintain a sense of satisfaction in relationships and adjustment, which in turn strength satisfaction with life (Berlin et al. 2008).

According to Bridges (2003), a large number of studies have shown that attachment during childhood influences social, emotional, and cognitive situations in later years, and attachment is a key factor for developmental well-being (e.g., life satisfaction). From an empirical standpoint, parental attachment has been positively associated with well-being and, more specifically, with life satisfaction. For example, Chen et al. (2017) found that higher paternal and maternal attachment were associated with higher global life satisfaction. Moreover, secure attachment to mothers and fathers predicted better individual adjustment outcomes (i.e., greater satisfaction) than did avoidant and anxious attachment patterns (Kumar and Mattanah 2016).

Similarly, several studies have explored associations between attachment insecurity and aspects of life satisfaction (Galinha et al. 2014; Karreman and Vingerhoets 2012; Lavy and Littman-Ovadia 2011; Li and Fung 2014; Temiz and Comert 2018). Overall, the results show that insecure attachment is inversely related to life satisfaction. These results have been obtained in a wide range of samples using cross-sectional, prospective, longitudinal, and cross-cultural designs (Shaver et al. 2010). Accordingly, secure parental attachment should have a direct impact on satisfaction with life.

Gratitude as a Mediator

Gratitude is considered a subjective feeling of thankfulness and appreciation for life and is usually regarded as a pleasant feeling that occurs when an individual receives a favor or benefits from others (McCullough et al. 2001). As a psychological state, gratitude is also considered to be a disposition, defined by the tendency to respond with grateful emotions to other people’s generosity and the ways in which others contribute to positive experiences and outcomes in one’s life (McCullough et al. 2002). Recently, scholars further suggested that gratitude is not only a disposition of perceiving benefits bestowed by another or by some impersonal source (McCullough et al. 2002) but also a wider life orientation toward noticing and appreciating the positive in the world (Wood et al. 2010).

As a positive experience in itself, gratitude may change the balance of experiences from negative to positive, leading to increased life satisfaction. Grateful people therefore tend to experience a sense of contentment in life more frequently than do ungrateful people (Emmons and McCullough 2003; McCullough et al. 2002, the issue was discussed in the conclusions and suggestions). Similarly, Watkins et al. (2003) found that individuals who scored higher in grateful personality traits reported greater life satisfaction, higher subjective well-being and more positive emotions than those with lower scores for those traits.

In past decades, numerous empirical studies highlighted the contribution of gratitude to life satisfaction (see Wood et al. 2010 for a review). Moreover, complimentary longitudinal evidence supports gratitude as a precursor of well-being (Wood et al. 2008). A few experimental studies have also found that gratitude interventions probably improve individuals’ well-being. For example, Emmons and McCullough (2003) showed that a gratitude journal intervention improved the life satisfaction of college students and adults with neuromuscular disorders. Recently, some scholars further evaluated the efficacy of gratitude interventions by using meta-analyses. For example, Davis et al. (2016) found that gratitude interventions outperformed a measurement-only control as well as alternative-activity condition on measures of psychological well-being, including life satisfaction and depression. Renshaw and Steeves (2016) also indicated that gratitude-based interventions are, on the whole, likely more effective than doing nothing different. Dickens (2017) further showed that gratitude interventions can have positive benefits for people in terms of their well-being, happiness, life satisfaction, grateful mood, grateful disposition, and positive affect, and they can result in decreases in depressive symptoms, but she also concluded that the field is left with a wide-open question as to what has more strength: a gratitude intervention’s positive influence or a negative intervention’s detriment?” (p. 204). This reminds us to explain carefully these results of gratitude interventions to avoid making untrue claims or causal inferences. Nevertheless, it seems difficult to disagree that gratitude is robustly related to life satisfaction based on prior findings of cross-sectional or longitudinal research (e.g., Wood et al. 2008, 2010).

On the other hand, secure parental attachment, consistent with the theory of attachment originally developed by Bowlby (1982), is a cultivation of positive experiences from which individuals come to believe they are worthy, other individuals are reliable, and the world is relatively safe (Luke et al. 2012). That is, when individuals’ attachment needs are satisfied, they can perceive being loved, valued, and affected and have a positive sense of self, others, and the world. This is in accord with the essence of gratitude (e.g., interpersonal and intrapersonal), which focuses on a wider life orientation toward appreciating others (e.g., help, kindness) and the world one lives in (e.g., an event, a beautiful day) (Lambert et al. 2009; Wood et al. 2010).

Moreover, some links between specific character strengths and attachment orientations have already been found. For example, Mikulincer et al. (2006) found that avoidance was associated with less dispositional gratitude and with experiencing gratitude as a negative feeling. Attachment insecurity was associated with a more ambivalent experience of gratitude-arousing interactions, as insecure individuals often felt that they were unworthy of other people’s kindness. Accordingly, attachment security should be associated with gratitude.

Empirically, healthy adjustment through parental attachment can lead to a multitude of favorable outcomes, including well-being and the development of positive virtues such as gratitude and humility (Dwiwardani et al. 2014). Research on character strengths has also shown that gratitude was the strength most highly and robustly linked to life satisfaction in a few studies (Park et al. 2004; Peterson et al. 2007). From these observations, attachment security might be associated with greater life satisfaction through higher levels of gratitude.

Study Aims

With the previously mentioned considerations in mind, the general purpose of the present study was to examine the associations between parental attachment (i.e., paternal and maternal attachment) and life satisfaction and to determine whether gratitude mediates the effect of parental attachment on life satisfaction. More specifically, this study aimed to analyze (a) the relative direct influences of paternal and maternal attachment on life satisfaction during emerging adulthood and (b) the potential mediating role of gratitude in the relationship between parental attachment and life satisfaction.

Three hypotheses were proposed. First, we expected that gratitude would be significantly associated with life satisfaction in emerging adulthood. Second, based on attachment theory, we hypothesized that both attachment to mothers and attachment to fathers would be directly and indirectly associated with life satisfaction through gratitude. However, given that mothers generally constitute the primary attachment figure upon whom individuals principally rely for meeting attachment needs across the developmental years (Freeman and Brown 2001), we expected to find a stronger effect between attachment to mothers and life satisfaction than between attachment to fathers and life satisfaction. This expectation is consistent with previous studies that showed that mothers are the relational fulcrum of family life, while fathers maintain a more peripheral position (Greene and Grimsley 1990; Noller and Callan 1990).

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Two hundred and eighty-five Taiwanese from five universities in Taiwan volunteered to participate in the study (mean age = 20.07 years, SD = 1.95 years), including freshmen to seniors, from different departments. Of these, 28.8% were public university students, and 71.2% were private university students. In the sample, 201 were females (70.5%), and 84 were males (29.5%). A multipart questionnaire was administered to the participants in a quiet classroom environment. Researchers instructed the students who took part in the study and then gave the students a set of questionnaires containing the items of the scales. The participants did not place their names on the measures, and the confidentiality of their responses was assured. It took approximately 15–20 min for the students to complete all the instruments.

Measures

Parental Attachment

To assess an individual’s level of attachment to his or her parental figures, the current study used the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA, Armsden and Greenberg 1987). Paternal and maternal attachment subscales, each with 25 items, were designed to measure the secure parental attachment of individuals toward their mothers and fathers. Responses to items were rated on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = almost never; 6 = almost always). For the paternal attachment items, participants assessed the extent of trust (e.g., “When I am angry about something, my father tries to be understanding”), communication (e.g., “My father encourages me to talk about my difficulties”), and alienation (e.g., “I get upset easily around my father”). Parallel wording for maternal scale items was used for assessing relationships with mothers. After reverse scoring of the negatively worded items and alienation items, the paternal and maternal attachment scores were the sum of the 25 respective items. Total scores range from 25 to 150, and higher scores indicate more secure parental attachment. The IPPA has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure in Chinese populations (Song et al. 2009). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients in this study were .96 for both the paternal and maternal attachment subscales.

Gratitude

To assess an individual’s level of gratitude, the current study used the Chinese version of the Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ; Chen et al. 2009). The GQ was designed to measure participants’ dispositional gratitude and includes five items (e.g., “I have so much in life to be thankful for”). Items were rated on a 6-point Likert scale, with response options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Total scores range from 6 to 30, and higher scores represent higher levels of dispositional gratitude. The scale was reported to have good internal consistency and satisfactory construct validity in Chinese populations (Lin 2014). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the GQ in this study was .87.

Life Satisfaction

To assess an individual’s level of satisfaction with his or her life, the current study used the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS, Diener et al. 1985). The SWLS was designed to measure participants’ global life satisfaction and includes five items (e.g., “I am satisfied with my life”). Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with each item on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree). Total scores range from 6 to 30, and higher scores indicate greater satisfaction with life. The Chinese version of the SWLS has been shown to be a reliable and valid scale for Chinese populations (Pan et al. 2016). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the SWLS in this study was .85.

Data Analyses

Model Goodness of Fit

Model goodness of fit was checked using several indices simultaneously (Bollen 1989). The first index was χ2: the model fits the data well when χ2 is not significant. However, the chi-square statistic is sensitive to sample size; therefore, we adopted additional fit indices that are less sensitive to sample size: CFI above .90 and SRMR less than .08 are considered acceptable (Hu and Bentler 1999).

Mediation Analyses

We used AMOS 20 to test a mediational model in which gratitude mediates the link between paternal and maternal attachment and life satisfaction. Bootstrap analyses were used to assess direct and indirect effects in the mediation model (Shrout and Bolger 2002). Bootstrapping statistics allowed us to examine the statistical significance of both direct and indirect effects. Mediation is found to be significant when 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (95% CI) of the indirect effects do not contain zero (MacKinnon et al. 2004). In the present study, parameter estimates were based on 2000 bootstrap samples.

Results

First, our results indicated that 49 individuals (17.2%) reported lower levels of satisfaction with life (i.e., a score below 15, out of 30 possible points). However, none reported lower levels of being grateful (i.e., a score below 15, out of 30 possible points). The means, standard deviations, and correlations among the study variables are presented in Table 1.

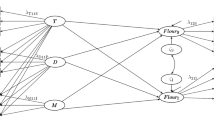

Second, the model fit indices of the mediational model showed an acceptable fit, χ2 (98) = 360.185, p < .001, CFI = .91, SRMR = .049, and explained 28% of the variance in life satisfaction (R2 = .280) (Fig. 1). The direct effects of paternal attachment (b = .184, SE = .005, p < .01), maternal attachment (b = .235, SE = .005, p < .001) and gratitude on life satisfaction (b = .307, SE = .066, p < .001) were all significant. Furthermore, both paternal attachment (b = .142, SE = .005, p < .05) and maternal attachment (b = .184, SE = .006, p < .01) were also significantly related to gratitude. We computed unstandardized indirect effects for each of 2000 bootstrapped samples, and a 95% bias-corrected confidence interval was used (Table 2). The initial total effect for paternal attachment was .228, and the mediation effect of gratitude (.043) explained 19% of the total effect. Likewise, the initial total effect for maternal attachment was .292, and the mediation effect of gratitude (.056) explained 19% of the total effect. The findings show that gratitude mediates the relationships between paternal and maternal attachment and life satisfaction.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to contribute to the literature on factors that can enhance life satisfaction by simultaneously considering the roles of parental attachment and gratitude. To this end, correlational analyses were conducted to examine the relationships among parental attachment, gratitude and life satisfaction.

First, the results of this study are congruent with previous research findings regarding the positive association between parental attachment and individuals’ life satisfaction (Chen et al. 2017; Guarnieri et al. 2015; Jiang et al. 2013; Kumar and Mattanah 2016; Pan et al. 2016). Likewise, the results also demonstrated a positive correlation between gratitude and life satisfaction, consistent with prior studies of linkages between gratitude and life satisfaction (Chan 2011; Emmons and McCullough 2003; Park et al. 2004; Peterson et al. 2007; Watkins et al. 2003). These findings support attachment theory (Bowlby 1982) and character strength (Park et al. 2004), which suggests that attachment and gratitude can significantly influence one’s development and mental health (e.g., life satisfaction).

Second, the findings revealed the positive relationship between parental attachment and the character strength of gratitude, suggesting that interactions with parents are important in shaping one’s dispositional gratitude. These results confirm the importance of parental attachment in the support of gratitude and emphasize how attachment security is related to the formation of gratitude (Mikulincer et al. 2006). According to attachment theory, when a child is securely attached, this results in stable trust of others, belief in the good will of others, and being loved and accepted by others in accordance with the essence of gratitude (Bowlby 1982; Shelton 1990). These results therefore lend support to the idea that the quality of attachment security can contribute to individuals’ grateful disposition.

Third, our results demonstrate that gratitude plays a significant mediating role in the association between life satisfaction and attachment to fathers and mothers. In other words, both paternal and maternal attachment were associated with greater life satisfaction through higher levels of gratitude. These findings support the notion that attachment that forms early in life (Bowlby 1982) has an effect on the preference and use of certain character strengths in emerging adulthood (e.g., gratitude), which may in turn induce individuals’ life satisfaction.

Additional interesting results of this study are found. One is that the mediation effects of gratitude explain approximately one-fifth of the total effects between paternal or maternal attachment and life satisfaction. This result implies that parental attachment still plays a relatively important role in life satisfaction. The findings suggest that both paternal and maternal attachment have not only direct impacts on life satisfaction but also an indirect influence on life satisfaction via gratitude. In other words, how satisfied adolescents feel about their lives overall is not only directly influenced by their levels of attachment to their parents but also indirectly affected by their levels of gratitude.

Another result is that maternal attachment was more strongly associated with gratitude than paternal attachment was. Likewise, the effect of maternal attachment on life satisfaction is also stronger than the effects of paternal attachment on life satisfaction. The findings implied that mother may play a more crucial role in individuals’ development within a family. This result is consistent with the theoretical perspective that mothers serve as the primary attachment figure across the developmental years (Freeman and Brown 2001). Thus, children’s security with their mother seems to be particularly important in the first years of life (Richaud de Minzi 2010). This is the first study that reports effects of gender differences of paternal and maternal attachment on gratitude and life satisfaction; therefore, this is still an area that needs further exploration.

Conclusions and Suggestions

A number of limitations in this study must be acknowledged. First, the present study was based solely on self-report measures, which may lead to mono-method bias. This type of data collection procedure may be a source of systematic bias that inflated relations among the constructs measured with the same method and informant. Thus, it can be concluded that more methodological effort in measuring study variables is needed in future studies. In addition, our findings were the outcome of a cross-sectional study. In this sense, the present study could, in correlational and descriptive terms, indicate that attachment is not only associated with gratitude but also able to strengthen well-being (i.e., life satisfaction). Further longitudinal studies are needed to provide support for this claim.

On the other hand, some issues should also be addressed. For example, in this study or even in some previous research, gratitude is usually considered a wider life orientation toward noticing and appreciating the positive in the world (Wood et al. 2010). If a person therefore is grateful, he will generally experience the various ways of viewing and interacting with the world (e.g., appreciation of other people, focus on what the person has and present moment). Consequently, grateful people tend to experience a sense of contentment in life more frequently than do ungrateful people (Emmons and McCullough 2003; McCullough et al. 2002). However, if people (a) can take “a more positive and appreciative outlook toward life” (thus being considered grateful) and yet (b) can typically fail to reciprocate to their benefactors (thus being considered ungrateful), there seems to be a conceptual conundrum with the definition of “gratitude” (e.g., people can apparently be simultaneously grateful and ungrateful). The possible problem is not answered in the current study because people who typically fail to reciprocate to their benefactors (and are therefore widely viewed as being ungrateful individuals) are still considered to be grateful according to our or some scholars’ view of gratitude (e.g., Wood et al. 2010; one who appreciates others or world may be regarded as grateful, but appreciation does not necessarily require any reciprocation to benefactors). From these perspectives, this conceptual conundrum is worth paying attention and trying to resolve in the future.

Nevertheless, the strengths of the current study help to extend previous research on parental attachment and psychological health in several ways. A primary strength is that we examined the different impacts of paternal and maternal attachment, highlighting the important role of paternal attachment in individuals’ psychological health. In addition, the results of this study provide a unique contribution to the literature by demonstrating the crucial role of gratitude in the relationship between parental attachment and life satisfaction. Specifically, the results emphasize that gratitude may serve as a key mechanism that accounts for the linkage between parental attachment and life satisfaction in young adults. Taken together, the findings suggest that effective parenting practices and school programming have important clinical implications. For example, therapeutic modalities that target disturbances in the attachment system or focus on improving family relationships in an attachment-oriented manner, such as attachment-based family therapy, may help to increase individuals’ overall satisfaction with life. Moreover, it would be valuable to involve parents in prevention/intervention programs by adding the component of teaching parents how to enhance gratitude through attachment relationships, social learning, and direct modeling or teaching. Froh et al. (2014) provided a good example of a school-based intervention program for individuals targeting gratitude.

In summary, the present study was an attempt to explore the relationships between parental attachment, gratitude, and life satisfaction in a Chinese population. We found that the direct associations between paternal and maternal attachment and life satisfaction were significant. Further, we found that gratitude played mediating roles in the association between parental attachment and life satisfaction during emerging adulthood. Based on our results of this study, it is beneficial to inform parents about how their children’s early attachment to them has a role in their children’s psychological development and health. Individuals perceived attachment security are more likely to develop the long-term disposition of gratitude, which in turn triggers greater life satisfaction and positive well-being.

References

Armsden, G. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (1987). The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16, 427–454.

Bartholomew, K., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Methods of assessing adult attachment: Do they converge? In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 25–45). New York: Guilford Press.

Berlin, L. J., Cassidy, J., & Appleyard, K. (2008). The influence of early attachments on other relationships. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 333–347). New York: Guilford.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley.

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. attachment (2nd ed.). New York: Basic Books (Original ed. 1969).

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. London: Routledge.

Bridges, L. J. (2003). Trust, attachment, and relatedness. In M. H. Bornstein, L. Davidson, C. L. M. Keyes, & K. A. Moore (Eds.), Well-being: Positive development across the life course (pp. 177–190). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Chan, D. W. (2011). Burnout and life satisfaction: Does gratitude intervention make a difference among Chinese school teachers in Hong Kong? Educational Psychology, 31(7), 809–823.

Chen, L. H., Chen, M.-Y., Kee, Y. H., & Tsai, Y.-M. (2009). Validation of the gratitude questionnaire (GQ) in Taiwanese undergraduate students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10, 655–664.

Chen, W., Zhang, D., Pan, Y., Hu, T., Liu, G., & Luo, S. (2017). Perceived social support and self-esteem as mediators of the relationship between parental attachment and life satisfaction among Chinese adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 108, 98–102.

Davis, D. E., Choe, E., Meyers, J., Wade, N., Varjas, K., Gifford, A., et al. (2016). Thankful for the little things: A meta-analysis of gratitude interventions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63, 20–31.

Dickens, L. R. (2017). Using gratitude to promote positive change: A series of meta-analyses investigating the effectiveness of gratitude interventions. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 39(4), 193–208.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302.

Diener, E., Diener, M., & Diener, C. (2009). Factors predicting the subjective well-being of nations. In E. Diener (Ed.), Culture and well-being. The collected works of Ed Diener (pp. 43–70). New York: Springer.

Dwiwardani, C., Hill, P. C., Bollinger, R. A., Marks, L. E., Steele, J. R., Doolin, H. N., et al. (2014). Virtues develop from a secure base: Attachment and resilience as predictors of humility, gratitude, and forgiveness. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 42, 83–90.

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 377–389.

Freeman, H., & Brown, B. (2001). Primary attachment to parents and peers during adolescence: Differences by attachment style. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30, 653–674.

Froh, J. J., Bono, G., Fan, J., Emmons, R. A., Henderson, K., Harris, C., Leggio, H., & Wood, A. M. (2014). Nice thinking! An educational intervention that teaches children to think gratefully. School Psychology Review, 43(2), 132–152.

Galinha, I. C., Oishi, S., Pereira, C. R., Wirtz, D., & Esteves, F. (2014). Adult attachment, love styles, relationship experiences and subjective well-being: Cross-cultural and gender comparison between Americans, Portuguese, and Mozambicans. Social Indicators Research, 119, 823–852.

Greenberg, M. T., Cicchetti, D., & Cummings, E. M. (1990). Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Greene, A. L., & Grimsley, M. D. (1990). Age and gender differences in adolescents’ preferences for parental advice: Mum’s the world. Journal of Adolescent Research, 5, 396–413.

Guarnieri, S., Smorti, M., & Tani, F. (2015). Attachment relationships and life satisfaction during emerging adulthood. Social Indicators Research, 121, 833–847.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Huebner, E. S. (2004). Research on assessment of life satisfaction of children and adolescents. Social Indicators Research, 66, 3–33.

Jiang, X., Huebner, E. S., & Hills, K. J. (2013). Parent attachment and early adolescents' life satisfaction: The mediating effect of hope. Psychology in the Schools, 50(4), 340–352.

Karen, R. (1994). Becoming attached: First relationships and how they shape our capacity to love. New York: Oxford University Press.

Karreman, A., & Vingerhoets, J. J. M. (2012). Attachment and well-being: The mediating role of emotion regulation and resilience. Personality and Individual Differences, 53, 821–826.

Kumar, S. A., & Mattanah, J. F. (2016). Parental attachment, romantic competence, relationship satisfaction, and psychosocial adjustment in emerging adulthood. Personal Relationships, 23, 801–817.

Lambert, N. M., Graham, S. M., & Fincham, F. D. (2009). A prototype analysis of gratitude: Varieties of gratitude experiences. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 1193–1207.

Lavy, S., & Littman-Ovadia, H. (2011). All you need is love? Strengths mediate the negative associations between attachment orientations and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 1050–1055.

Lawler-Row, K. A., Younger, J. W., Piferi, R. L., & Jones, W. H. (2006). The role of adult attachment style in forgiveness following an interpersonal offense. Journal of Counseling and Development, 84, 493–502.

Li, T., & Fung, H. H. (2014). How avoidant attachment influences subjectivewell-being: An investigation about the age and gender differences. Aging & Mental Health, 18, 4–10.

Lin, C.-C. (2014). A higher-order gratitude uniquely predicts subjective wellbeing: Incremental validity above the personality and a single gratitude. Social Indicators Research, 119, 909–924.

Luke, M. A., Sedikides, C., & Carnelley, K. (2012). Your love lifts me higher! The energizing quality of secure relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38, 721–733.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 99–128.

Martikainen, L. (2012). The family environment in adolescence as a predictor of life satisfaction in adulthood. In M. Vassar (Ed.), Psychology of life satisfaction (pp. 19–30). New York: Nova Science Publishers.

McCullough, M. E., Kilpatrick, S. D., Emmons, R. A., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychological Bulletin, 127(2), 249–266.

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. A. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 112–127.

Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P. R., & Slav, K. (2006). Attachment, mental representations of others, and gratitude and forgiveness in romantic relationships. In M. Mikulincer & G. Goodman (Eds.), Dynamics of romantic love: Attachment, caregiving, and sex (pp. 190–215). New York: Guildford Press.

Noller, P., & Callan, V. J. (1990). Adolescents’ perceptions of the nature of their communication with parents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 19, 349–362.

Pan, Y., Zhang, D., Liu, Y., Ran, G., & Teng, Z. (2016). Different effects of paternal and maternal attachment on psychological health among Chinese secondary school students. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 2998–3008.

Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23, 603–619.

Peterson, C., Ruch, W., Beermann, U., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2007). Strengths of character, orientations to happiness, and life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2, 149–156.

Proctor, C. L., & Linley, P. A. (2014). Life satisfaction in youth. In G. A. Fava & C. Ruini (Eds.), Increasing psychological well-being in clinical and educational settings, cross-cultural advancements in positive psychology (pp. 199–215). New York: Springer.

Proctor, C. L., Linley, P. A., & Maltby, J. (2009). Youth life satisfaction: A review of the literature. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10, 583–630.

Renshaw, T. L., & Steeves, R. M. O. (2016). What good is gratitude in youth and schools? A systematic review and meta-analysis of correlates and intervention outcomes. Psychology in the Schools, 53(3), 286–305.

Richaud de Minzi, M. (2010). Gender and cultural patterns of Mothers' and Fathers' attachment and links with Children's self-competence, depression and loneliness in middle and late childhood. Early Child Development and Care, 180(1&2), 193–209.

Shaver, P. R., Mikulincer, M., Alonso-Arbiol, I., & Lavy, S. (2010). Assessment of adult attachment across cultures: Conceptual and methodological considerations. In P. Erdman, K. M. Ng, & S. Metzger (Eds.), Attachment: Expanding the cultural connections (pp. 89–108). New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

Shelton, C. M. (1990). Morality of the heart: A psychology for the Christian moral life. New York: Crossroad.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445.

Song, H., Thompson, R. A., & Ferrer, E. (2009). Attachment and self-evaluation in Chinese adolescents: Age and gender differences. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 1267–1286.

Steger, M. F., Oishi, S., & Kesebir, S. (2011). Is a life without meaning satisfying? The moderating role of the search for meaning in satisfaction with life judgments. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6, 173–180.

Temiz, Z. T., & Comert, I. T. (2018). The relationship between life satisfaction, attachment styles, psychological resilience in university students. Dusunen Adam The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences, 31, 274–283.

Tov, W., & Diener, E. (2009). Culture and subjective well-being. In E. Diener (Ed.), Culture and well-being. The collected works of Ed Diener (pp. 9–42). New York: Springer.

Watkins, P. C., Woodward, K., Stone, Y., & Kolts, R. L. (2003). Gratitude and happiness: Development of a measure of gratitude, and relationships with subjective well-being. Social Behavior and Personality, 31(5), 431–452.

Whittaker, K. A., & Cornthwaite, S. (2000). Benefits for all: Outcomes from a positive parenting evaluation study. Clinical Effectiveness in Nursing, 4, 189–197.

Wood, A. M., Maltby, J., Gillett, R., Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. (2008). The role of gratitude in the development of social support, stress, and depression: Two longitudinal studies. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 854–871.

Wood, A. M., Froh, J. J., & Geraghty, A. (2010). Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 890–905.

Funding

This study was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the Republic of China in Taiwan (Contract MOST 105–2410-H-027-010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that he/she has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, CC. Attachment and life satisfaction in young adults: The mediating effect of gratitude. Curr Psychol 39, 1513–1520 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00445-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00445-0