Abstract

Narcissism and self-esteem are both characterized by positive forms of self-regard, and common sense would suggest that these two constructs should be strongly and positively related. However, research has demonstrated that the associations between narcissism and self-esteem are quite complex and that there are critical differences between the two constructs that contribute to this complexity. This chapter aims to highlight some of these intricate relationships and important conceptual differences with a focus on three specific areas. First, we outline key differences in the content of the positive self-views that are associated with each construct. For example, narcissistic self-views are, by definition, exaggerated and overblown, whereas the self-views of individuals with high self-esteem may or may not be accurate. Second, we discuss how various conceptualizations of narcissism (e.g., the narcissistic admiration and rivalry concept [NARC] model) and self-esteem (e.g., fragile versus secure forms of high self-esteem) inform our understanding of their association with each other. Lastly, we review proposed evolutionary origins of both constructs (e.g., sociometer and hierometer theories) that may shed light on the potential functions of narcissism and self-esteem in the social lives of humans.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Grandiose narcissism

- Self-esteem

- Implicit self-esteem

- Psychodynamic mask model of narcissism

- Self-esteem instability

- Narcissistic admiration and rivalry concept

- Sociometer

- Hierometer

Narcissism is characterized by exaggerated feelings of grandiosity, vanity, self-absorption, and entitlement (e.g., Emmons, 1984; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001; Raskin & Terry, 1988).Footnote 1 Narcissistic individuals believe they are superior to others, feel that they are entitled to privileges and special treatment, and crave the respect and admiration of others. However, these grandiose self-views may be quite fragile, with narcissistic individuals being highly reactive to potential threats to their self-esteem (e.g., Akhtar & Thomson, 1982; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001; Rhodewalt & Morf, 1995). Self-esteem can be defined as a global, affective evaluation of the self that can range from very positive (i.e., high self-esteem) to very negative (i.e., low self-esteem; Rosenberg, 1965). Intuitively, it would seem that narcissism and self-esteem should be strongly and positively related, as both constructs involve positive self-regard. Indeed, as highlighted by Brummelman and colleagues, psychologists have frequently described narcissism using terms such as “unrealistically high self-esteem,” “inflated self-esteem,” and “defensive high self-esteem” (Brummelman, Gürel, Thomaes, & Sedikides, this volume; Brummelman, Thomaes, & Sekikides, 2016). However, research has revealed that the associations between narcissism and self-esteem are quite complex, and there are critical differences between these two constructs (e.g., Bosson & Weaver, 2011; Brummelman et al., 2016; Campbell, Rudich, & Sedikides, 2002). The purpose of the present chapter is to highlight the complex connections between narcissism and self-esteem. We chose to focus this review on three specific areas. First, we discuss proposed differences in the content of the positive self-views associated with both constructs. Next, we review how different conceptualizations of narcissism and self-esteem may inform our understanding of their relationship with each other. Lastly, we consider proposed evolutionary origins of both constructs and how those origins may further our understanding of the potential functions of narcissism and self-esteem in the social lives of humans.

Connections Between Narcissism and Self-Esteem: Content of Self-Views

Both narcissistic individuals and those with high self-esteem hold relatively positive views of themselves (e.g., Brown & Zeigler-Hill, 2004; Raskin, Novacek, & Hogan, 1991). However, it is important to note that despite the conceptual similarities between narcissism and self-esteem, the correlation between these constructs is often relatively weak and somewhat inconsistent across studies (i.e., it is often less than 0.30; Brown & Zeigler-Hill, 2004). This weak association between narcissism and self-esteem may be due, at least in part, to the fact that individuals with high levels of self-esteem vary considerably in their levels of narcissism, whereas individuals with low self-esteem rarely report particularly high levels of narcissism (Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, & Vohs, 2003).

There are also important differences in the positive self-views that are adopted by narcissistic individuals and those held by individuals with high self-esteem. First, self-esteem is purely evaluative such that an individual’s level of self-esteem simply reflects how that person views oneself. In contrast, narcissism appears to possess motivational properties in addition to its evaluative elements such that narcissistic individuals not only hold extremely positive self-views, but they also want to think highly of themselves (Bushman & Baumeister, 1998). The intense desire that narcissistic individuals have to feel good about themselves has led Baumeister and Vohs (2001) to suggest that they may actually be “addicted” to self-esteem. Second, the very definition of narcissism involves exaggerated self-views, whereas the self-views of individuals with high self-esteem may or may not be accurate. For example, narcissistic individuals often view themselves more positively than they are viewed by others (e.g., they rate themselves as being more intelligent and attractive than others see them as being; Gabriel, Critelli, & Ee, 1994). However, narcissistic individuals do not inflate their self-views in every area. Rather, they tend to exaggerate their agentic qualities (e.g., intelligence) but not their communal traits (e.g., agreeableness; Campbell, Bosson, Goheen, Lakey, & Kernis, 2007; Campbell et al., 2002; Konrath, Bushman, & Grove, 2009). Third, Brummelman et al. (2016) recently proposed an important difference between the self-views of narcissistic individuals and those of individuals with high self-esteem . Brummelman et al. suggest that narcissistic individuals believe they are superior to others, whereas individuals with high self-esteem are simply satisfied with themselves and do not necessarily feel that they are better than others (see Brummelman et al., this volume for an extended discussion).

Conceptualizations of Self-Esteem and Narcissism

Associations between self-esteem and narcissism are quite complex, which is due, in part, to various conceptualizations and expressions of both constructs. Importantly, researchers have demonstrated the value of considering aspects of self-esteem beyond its level (i.e., whether self-esteem level is high or low) and have highlighted distinctions between secure and fragile forms of self-esteem (see Kernis, 2003, 2005, for reviews). Of particular importance to the present chapter are distinctions between implicit and explicit forms of self-esteem, as well as stable and unstable forms of self-esteem. Researchers have also advanced multidimensional conceptualizations of narcissism (e.g., Ackerman et al., 2011; Back et al., 2013; Emmons, 1984, 1987; Raskin & Terry, 1988). Most recently, Back et al. (2013) proposed the narcissistic admiration and rivalry concept (NARC; Back et al., 2013) which distinguishes between assertive (i.e., narcissistic admiration) and antagonistic (i.e., narcissistic rivalry) aspects of narcissism, which are involved in the maintenance of grandiose self-views through different strategies. We now turn to discussion of how these various conceptualizations of self-esteem and narcissism inform our understanding of the complex associations between the two constructs.

Implicit Self-Esteem and the Psychodynamic Mask Model of Narcissism

A frequent question that arises when considering the connection between narcissism and self-esteem is whether narcissistic individuals actually feel as good about themselves as it appears on the surface. That is, are the grandiose self-views of narcissistic individuals expressions of authentic self-love or are these exceptionally positive self-views merely a façade that is used to hide deep-seated feelings of inferiority? The idea that the grandiose self-views expressed by narcissistic individuals are not entirely genuine has its origins in psychodynamic formulations of narcissism (e.g., Kernberg, 1975; Kohut, 1966) and has sometimes been referred to as the psychodynamic mask model of narcissism (e.g., Bosson et al., 2008; Southard, Noser, & Zeigler-Hill, 2014; Zeigler-Hill & Jordan, 2011 for reviews). Elements of this perspective can still be found in various contemporary views of narcissism such as the dynamic self-regulatory model of narcissism (Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001) as well as the diagnostic criteria for narcissistic personality disorder which specifies that the self-esteem of narcissistic individuals is “almost invariably very fragile” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, p. 670).

The idea that narcissistic individuals harbor low self-esteem has been of considerable interest to researchers, but it has been exceptionally difficult to find a means for getting behind the grandiose façade that narcissistic individuals present to the world – if that is indeed what narcissistic individuals are actually doing. One potentially promising approach was the development of nonreactive tasks intended to capture implicit self-esteem (i.e., nonconscious feelings of self-worth; see Zeigler-Hill & Jordan, 2010, for a review), as opposed to explicit self-esteem (i.e., deliberative, conscious self-views; e.g., Zeigler-Hill & Jordan, 2011). Explicit self-esteem is typically assessed by simply asking individuals to rate their level of agreement with statements such as “I feel that I’m a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others” (Rosenberg, 1965). In contrast, measures of implicit self-esteem attempt to unobtrusively assess unconscious feelings of self-worth via automatic responses and measures that are less susceptible to socially desirable response biases. Although multiple measures have been developed to assess implicit self-esteem (see Bosson, Swann, & Pennebaker, 2000 or Fazio & Olson, 2003, for reviews), one of the most widely used measures is the implicit association test (IAT; Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, 1998). The IAT assesses participants’ reaction time in distinguishing between pleasant (e.g., love, happy) and unpleasant (e.g., filth, hatred) words, as well as self (e.g., I, me) and not-self (i.e., you, them) words that are presented on a computer screen by pressing separate keys on a keyboard. During the critical trials of the procedure, respondents make both discriminations (pleasant vs. unpleasant, self vs. not-self) on alternate trials using only one pair of keys. In one phase, self and unpleasant words share a response key and not-self and pleasant words share the other response key. This phase should be relatively difficult for individuals with high implicit self-esteem because the self is being linked with unpleasant stimuli which should result in slower responses. In the other phase, self and pleasant words share a response key and not-self and unpleasant words share the other response key. This phase should be comparatively easier for individuals with high implicit self-esteem leading to faster responses . Scores are calculated by subtracting average response times during the phase when self and pleasant words share a key from the average response times during the phase when self and unpleasant words share a key.

If the grandiose self-views of narcissistic individuals are really masking implicit feelings of low self-worth, then those scoring high on measures of narcissism should be expected to self-report higher levels of explicit self-esteem and score lower on measures of implicit self-esteem. Initial studies involving implicit measures of self-esteem such as the IAT supported the idea that narcissistic individuals have hidden feelings of low self-worth by showing that they reported high levels of self-esteem as assessed via traditional self-report strategies, but possessed low levels of implicit self-esteem using these recently developed nonreactive measures (Jordan, Spencer, Zanna, Hoshino-Browne, & Correll, 2003; Zeigler-Hill, 2006). For example, using the IAT, Jordan et al. (2003) found that individuals with the combination of high explicit self-esteem and low implicit self-esteem reported the highest levels of narcissism (i.e., scores on the Narcissistic Personality Inventory; Raskin & Hall, 1979, 1981), and a similar pattern was found by Zeigler-Hill (2006) using the IAT and another measure of implicit self-esteem. However, despite the promise of these early studies, subsequent research has failed to consistently replicate this basic pattern (Bosson et al., 2008; Campbell et al., 2007; Gregg & Sedikides, 2010; see Zeigler-Hill & Jordan, 2011, for an extended discussion of this issue).

One reason for the inconsistent results regarding the associations between narcissism and implicit and explicit self-esteem may be the fact that measures of implicit self-esteem possess weak psychometric properties (see Bosson et al., 2000 or Zeigler-Hill & Jordan, 2010 for extended discussions). As a result, Myers and Zeigler-Hill (2012) attempted to clarify the extent to which narcissistic individuals actually like themselves by moving away from reliance on indicators of implicit self-esteem and instead employed a bogus pipeline technique. The bogus pipeline procedure is a laboratory technique that promotes honesty by convincing participants that the researchers will know if they attempt to lie through the use of physiological equipment (i.e., a lie detector). During Phase 1 of their study, Myers and Zeigler-Hill collected participants’ self-reported levels of narcissism (i.e., NPI scores) and self-esteem (i.e., the State Self-esteem Scale; Heatherton & Polivy, 1991) online and then in Phase 2 randomly assigned participants to either a bogus pipeline condition or a control condition. In the bogus pipeline condition, participants were connected to physiological equipment (i.e., galvanic skin response, automatic blood pressure monitor, and a Grass Model 78D polygraph) while seated in a recliner and told that the experimenter would know if they were lying. Then, participants read each item of the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965) aloud and verbally provided their responses. The control condition was identical to the bogus pipeline condition except that participants were told they were only connected to the physiological equipment so the experimenter could gain practice with the equipment, and the experimenter clearly turned off all the physiological equipment before participants verbally completed the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale. The results of this study were consistent with the idea that narcissistic individuals do not actually feel as good about themselves as it appears on the surface because narcissistic individuals reported lower levels of self-esteem in the bogus pipeline condition than in the control condition. Although those results were initially quite promising, Brunell and Fisher (2014) used a similar bogus pipeline approach and failed to replicate this basic pattern. Taken together, the inconsistent results across these studies involving measures of implicit self-esteem and the bogus pipeline procedure have left researchers without a clear understanding of how narcissistic individuals truly feel about themselves (e.g., Kuchynka & Bosson, 2018; Jordan & Zeigler-Hill, 2013).

Self-Esteem Instability and Reactivity to Daily Events

Another approach to understanding the complex associations between narcissism and self-esteem has been to consider self-esteem instability (i.e., the extent to which moment-to-moment feelings of self-worth tend to fluctuate over time; Kernis, 2003). It would certainly appear that self-esteem instability should have considerable overlap with narcissism. For example, both narcissism and self-esteem instability are associated with similar strategies for self-enhancement and self-protection (see Jordan & Zeigler-Hill, 2013, for a review). Despite these apparent similarities, the connection between narcissism and self-esteem instability has been inconsistent such that these constructs have been found to be positively associated in some studies (e.g., Rhodewalt, Madrian, & Cheney, 1998) but not in others (e.g., Bosson et al., 2008; Webster, Kirkpatrick, Nezlek, Smith, & Paddock, 2007; Zeigler-Hill, 2006; Zeigler-Hill, Chadha, & Osterman, 2008).

One possible explanation for the inconsistent associations between narcissism and self-esteem instability is that the self-esteem of narcissistic individuals is not generally unstable. Rather, the self-esteem of narcissistic individuals may only be reactive to specific types of events. Consistent with this possibility, narcissistic individuals tend to be especially reactive to failures in their daily lives (e.g., doing poorly on a work task; Zeigler-Hill & Besser, 2013; Zeigler-Hill, Myers, & Clark, 2010). For example, Zeigler-Hill et al. (2010) used a daily diary procedure to examine associations between narcissism, fluctuations in self-esteem, and daily social and achievement events. Their results indicated that the self-esteem of narcissistic individuals was especially reactive to negative achievement events (e.g., failing to meet a daily goal), but not positive achievement events (e.g., being complimented on one’s abilities). It is possible that the heightened reactivity of narcissistic individuals to negative achievement-based events may be due to these experiences being especially likely to undermine the inflated self-views these individuals hold regarding their agentic characteristics (e.g., intelligence, competence), whereas positive achievement-based events simply confirm their grandiose self-views and expectations of success.

Conceptualization of Narcissism and Self-Esteem Instability

Many of the studies that have examined the connection between narcissism and self-esteem instability have been guided by a unidimensional view of narcissism that has been criticized for various reasons during recent years (e.g., psychometric concerns about the instruments used to assess narcissism; Brown, Budzek, & Tamborski, 2009). One attempt to address these concerns was the development of the narcissistic admiration and rivalry concept (NARC; Back et al., 2013), which is a two-dimensional model of narcissism that distinguishes between narcissistic admiration (i.e., an agentic strategy characterized by assertive self-enhancement and self-promotion) and narcissistic rivalry (i.e., an antagonistic strategy characterized by self-protection and self-defense). Although research concerning the NARC model is still in its earliest stages, these distinct agentic and antagonistic forms of narcissism may provide some insight concerning the inconsistent associations between narcissism and self-esteem instability that emerged in previous studies.

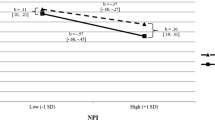

Geukes et al. (2017) examined whether narcissistic admiration and narcissistic rivalry differed in their associations with self-esteem level and self-esteem instability across three studies. They reasoned that narcissistic admiration should be associated with higher and relatively stable self-esteem because admiration is characterized by a self-enhancing strategy involving self-praise, assertive actions, and social potency, whereas narcissistic rivalry should be associated with lower and more unstable self-esteem because rivalry is characterized by self-protective, defensive strategies that are likely to lead to social conflict. The results of Geukes et al. revealed that narcissistic admiration was consistently associated with higher levels of self-esteem, but its connections with self-esteem instability were inconsistent across three studies (i.e., a negative association emerged in one study, but there was no association in the other two studies). In contrast, narcissistic rivalry had a consistent positive association with self-esteem instability (i.e., unstable self-esteem), but its connection with self-esteem level was inconsistent across three studies (i.e., a negative association emerged in two studies, but there was no association in the other study).

Zeigler-Hill et al. (in press) found results that were conceptually similar to those of Geukes et al. (2017) such that narcissistic admiration was positively associated with self-esteem level, whereas narcissistic rivalry was positively associated with self-esteem instability. In addition, Zeigler-Hill et al. (in press) found that the daily self-esteem levels of individuals with high levels of narcissistic admiration were particularly reactive to changes in their perceived levels of daily status (i.e., being respected and viewed as important). This finding suggests the intriguing possibility that the feelings of self-worth that are connected with the agentic form of narcissism may be intimately linked with status (i.e., the belief that one is respected and admired by others). Taken together, the results of Geukes et al. (2017) and Zeigler-Hill et al. (in press) suggest that accounting for the multiple facets of narcissism – such as distinguishing between its agentic and antagonistic forms – may be important for gaining a more nuanced understanding of the connections that narcissism has with different aspects of self-esteem .

Potential Evolutionary Origins of Narcissism and Self-Esteem

In order to better understand the complex associations between narcissism and self-esteem, it may be helpful to consider why these two constructs might exist in the first place. Studies have shown that both narcissism and self-esteem are moderately heritable (e.g., Neiss, Sedikides, & Stevenson, 2002; Vernon, Villani, Vickers, & Harris, 2008) which suggests there may be some adaptive benefits associated with both constructs. One potential benefit associated with narcissism is that it promotes an alternative reproductive strategy that is focused on short-term mating opportunities (e.g., Holtzman, this volume; Holtzman & Strube, 2011). When more than one mating strategy exists in a population, the frequency with which each strategy is adopted has implications for its level of success (i.e., frequency-dependent selection) such that the strategy that is adopted less often will sometimes yield relatively large benefits (e.g., Buss, 2009). Since long-term pair-bonding is the primary mating strategy for humans, narcissistic individuals may experience heightened reproductive success by employing alternative short-term mating strategies. Consistent with this idea, narcissistic individuals report a preference for short-term mating strategies (e.g., Jonason, Li, Webster, & Schmitt, 2009), are relatively promiscuous (e.g., Reise & Wright, 1996), and are less discerning than others when choosing short-term mating partners (e.g., Jonason, Valentine, Li, & Harbeson, 2011). These findings suggest the interesting possibility that – despite its association with an array of negative interpersonal outcomes (e.g., lack of empathy; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001) – narcissism may persist in the population because of the reproductive benefits it provides.

Although narcissism may persist in the population due to its short-term reproductive benefits, self-esteem may have originated as a means for maintaining and enhancing social inclusion. According to sociometer theory (Leary, 1999; Leary, Tambor, Terdal, & Downs, 1995), humans have a fundamental need to belong (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). This drive to establish and maintain interpersonal relationships is believed to have evolved because the survival and reproductive fitness of early humans depended on belonging to a social group. Thus, our ancestors are thought to have evolved a psychological system (i.e., a sociometer) that monitors the extent to which an individual is valued and accepted by others that would have been adaptive given the likely devastating implications of being ostracized or rejected from their social groups (e.g., limited access to resources or potential mates). The “output” of the sociometer system is state self-esteem (i.e., an individual’s feelings of self-worth at a particular moment).

According to sociometer theory, state self-esteem is believed to rise and fall in conjunction with one’s perceptions of his or her relational value. That is, state self-esteem should increase in response to cues of social acceptance (e.g., praise, love) and decrease in response to cues of social rejection or reductions in relational value (e.g., criticism, failure; Leary, 1999). Consistent with this idea, studies have shown that participants tend to report lower state self-esteem after experiencing rejection (e.g., Leary, Cottrell, & Phillips, 2001; Leary, Haupt, Strausser, & Chokel, 1998; Leary et al., 1995; Zadro, Williams, & Richardson, 2004), but this pattern has failed to emerge in some studies (e.g., Bernstein et al., 2013; Blackhart, Nelson, Knowles, & Baumeister, 2009). Sociometer theory also argues that decreases in state self-esteem should motivate individuals to engage in compensatory, affiliative behaviors that are intended to reestablish social inclusion. Past studies have found support for this aspect of sociometer theory by showing that individuals who experience rejection are more interested in forming new relationships (Maner, DeWall, Baumeister, & Schaller, 2007) and conforming to group norms (Williams, Cheung, & Choi, 2000). In addition, individuals with low levels of self-esteem tend to be very cautious, conservative, and restrained in their interactions with others which may be largely due to their desire to avoid rejection (e.g., Anthony, Wood, & Holmes, 2007; Haupt & Leary, 1997; Murray, Rose, Bellavia, Holmes, & Kusche, 2002). Taken together, these findings suggest that self-esteem may have evolved as a means for helping humans navigate complex social environments.

Recently, Mahadevan, Gregg, Sedikides, and de Waal-Andrews (2016) proposed hierometer theory which argues that both self-esteem and narcissism evolved to help individuals navigate status hierarchies. Status hierarchies are pervasive among humans (e.g., Sidanius & Pratto, 1999) and, because there are benefits to being at the top of this hierarchy (e.g., greater reproductive success; von Rueden, Gurven, & Kaplan, 2011), humans likely evolved a psychological system to aid in navigating them. On a conceptual level, the theoretical underpinnings of hierometer theory are similar to those of sociometer theory. That is, they both suggest that self-regard helps individuals track their social value. However, whereas sociometer theory argues that state self-esteem tracks relational value (e.g., perceptions of acceptance, liking, and affiliation) and regulates affiliative behaviors aimed at increasing social inclusion, hierometer theory argues that both self-esteem and narcissism track instrumental value (e.g., perceptions of respect and admiration) and regulate assertive behavior aimed at gaining status. Previous studies have provided some initial support for hierometer theory. For example, Leary et al. (2001) found that self-esteem changes in accordance with feedback concerning status such that individuals who perceive themselves to be in a relatively dominant social position tend to report higher levels of self-esteem . In addition, Mahadevan et al. (2016) found that the combination of self-esteem and narcissism fully mediated the associations that status and inclusion had with assertiveness and affiliation, respectively. Further, Zeigler-Hill et al. (in press) found that state self-esteem increased on days when individuals perceived themselves as having higher levels of status even when statistically controlling for perceived inclusion, which suggests that this hierometer process (i.e., state self-esteem changing in accordance with status) is distinct from the sociometer process (i.e., state self-esteem changing in accordance with relational value). Together, these studies provide preliminary evidence that supports the existence of the hierometer system.

Considering the current evidence for sociometer theory and hierometer theory, it seems that self-esteem may be entwined with both inclusion and status, whereas narcissism seems to be primarily associated with status (see Zeigler-Hill, McCabe, Vrabel, Raby, & Cronin, this volume, for an extended discussion). The sociometer and hierometer systems likely evolved in humans because there are tremendous adaptive benefits for gaining social inclusion and successfully navigating social hierarchies. Thus, one possibility is that self-esteem and narcissism may have evolved to serve similar, but not completely identical, functions for humans.

Conclusion

In summary, the connections between narcissism and self-esteem are quite complex. Although narcissism is generally associated with higher levels of self-esteem, this connection is relatively weak and not as straightforward as one might expect (e.g., Brown & Zeigler-Hill, 2004). There appear to be inherent differences in the content of the self-views possessed by narcissistic individuals and those with high self-esteem. There are also differing conceptualizations of the two constructs. For example, it has often been suggested that narcissistic individuals possess self-esteem that is inherently fragile, and advances in the measurement of implicit self-esteem seemed to be an initially promising avenue for testing this possibility. However, support for the idea that narcissistic grandiosity masks deep feelings of low self-worth has been inconsistent across studies (e.g., Bosson et al., 2008).

Recent research has further expanded conceptualizations of narcissism and found that the agentic aspects of the construct (i.e., narcissistic admiration) tend to be associated with higher levels of self-esteem, whereas the antagonistic aspects of narcissism (i.e., narcissistic rivalry) tend to be associated with more unstable self-esteem (Geukes et al., 2017; Zeigler-Hill et al., in press). It would be helpful for future studies to provide a more careful and thorough examination of the conditions under which different aspects of narcissism are associated with self-esteem. For example, Zeigler-Hill et al. (in press) found that the self-esteem of individuals with high levels of narcissistic admiration tends to be highly reactive to perceived status but not perceived inclusion. This is consistent with the tendency for narcissistic individuals to care far more about being respected and admired than about being liked. These results might also help to clarify the potential evolutionary origins of self-esteem and narcissism, which current theorizing suggest are tied to social inclusion and the successful navigation of status hierarchies. Additional research examining the interconnections between narcissism, status, and self-esteem may help resolve the inconsistent results that have emerged concerning the fragile nature of narcissistic self-esteem. We hope that future research will provide a more nuanced understanding of the connections between narcissism and self-esteem because we believe these advancements will provide additional insights into the intrapsychic processes and interpersonal behaviors that characterize narcissistic individuals.

References

Ackerman, R. A., Witt, E. A., Donnellan, M., Trzesniewski, K. H., Robins, R. W., & Kashy, D. A. (2011). What does the narcissistic personality inventory really measure? Assessment, 18, 67–87.

Akhtar, S., & Thomson, J. A. (1982). Overview: Narcissistic personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 139, 12–20.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Anthony, D. B., Wood, J. V., & Holmes, J. G. (2007). Testing sociometer theory: Self-esteem and the importance of acceptance for social decision-making. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43, 425–432.

Back, M. D., Küfner, A. C., Dufner, M., Gerlach, T. M., Rauthmann, J. F., & Denissen, J. J. (2013). Narcissistic admiration and rivalry: Disentangling the bright and dark sides of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105, 1013–1037.

Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4, 1–44.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529.

Baumeister, R. F., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Narcissism as addiction to esteem. Psychological Inquiry, 12, 206–210.

Bernstein, M. J., Claypool, H. M., Young, S. G., Tuscherer, T., Sacco, D. F., & Brown, C. M. (2013). Never let them see you cry: Self-presentation as a moderator of the relationship between exclusion and self-esteem. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, 1293–1305.

Blackhart, G. C., Nelson, B. C., Knowles, M. L., & Baumeister, R. F. (2009). Rejection elicits emotional reactions but neither causes immediate distress nor lowers self-esteem: A meta-analytic review of 192 studies on social exclusion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 13, 269–309.

Bosson, J. K., Lakey, C. E., Campbell, W. K., Zeigler-Hill, V., Jordan, C. H., & Kernis, M. H. (2008). Untangling the links between narcissism and self-esteem: A theoretical and empirical review. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 1415–1439.

Bosson, J. K., Swann, W. B., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2000). Stalking the perfect measure of implicit self-esteem: The blind men and the elephant revisited? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 631–643.

Bosson, J. K., & Weaver, J. R. (2011). “I love me some me”: Examining the links between narcissism and self-esteem. In W. K. Campbell & J. D. Miller (Eds.), The handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder: Theoretical approaches, empirical findings, and treatments (pp. 261–271). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Brown, R. P., Budzek, K., & Tamborski, M. (2009). On the meaning and measure of narcissism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 951–964.

Brown, R. P., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2004). Narcissism and the non-equivalence of self-esteem measures: A matter of dominance? Journal of Research in Personality, 38, 585–592.

Brummelman, E., Gürel, C., Thomaes, S., & Sedikides, C. (this volume). What separates narcissism from self-esteem? A social-cognitive perspective. In A. D. Hermann, A. B. Brunell, & J. D. Foster (Eds.), The handbook of trait narcissism: Key advances, research methods, and controversies. New York: Springer.

Brummelman, E., Thomaes, S., & Sekikides, C. (2016). Separating narcissism from self-esteem. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25, 8–13.

Brunell, A. B., & Fisher, T. D. (2014). Using the bogus pipeline to investigate grandiose narcissism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 55, 37–42.

Bushman, B. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Threatened egotism, narcissism, self-esteem, and direct and displaced aggression: Does self-love or self-hate lead to violence? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 219–229.

Buss, D. M. (2009). How can evolutionary psychology successfully explain personality and individual differences? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 359–366.

Campbell, W. K., Bosson, J. K., Goheen, T. W., Lakey, C. E., & Kernis, M. H. (2007). Do narcissists dislike themselves “deep down inside”? Psychological Science, 18, 227–229.

Campbell, W. K., Rudich, E. A., & Sedikides, C. (2002). Narcissism, self-esteem, and the positivity of self-views: Two portraits of self-love. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 358–368.

Emmons, R. A. (1984). Factor analysis and construct validity of the narcissistic personality inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48, 291–300.

Emmons, R. A. (1987). Narcissism: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 11–17.

Fazio, R. H., & Olson, M. A. (2003). Implicit measures in social cognition research: Their meaning and uses. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 297–327.

Gabriel, M. T., Critelli, J. W., & Ee, J. S. (1994). Narcissistic illusions in self-evaluations of intelligence and attractiveness. Journal of Personality, 62, 143–155.

Gebauer, J. E., Sedikides, C., Verplanken, B., & Maio, G. R. (2012). Communal narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103, 854–878.

Geukes, K., Nestler, S., Hutteman, R., Dufner, M., Küfner, A. C., Egloff, B., et al. (2017). Puffed-up but shaky selves: State self-esteem level and variability in narcissists. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112, 769–786.

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1464–1480.

Gregg, A. P., & Sedikides, C. (2010). Narcissistic fragility: Rethinking its links to explicit and implicit self-esteem. Self and Identity, 9, 142–161.

Haupt, A. L., & Leary, M. R. (1997). The appeal of worthless groups: Moderating effects of trait self-esteem. Group Dynamics, 1, 124–132.

Heatherton, T. F., & Polivy, J. (1991). Development and validation of a scale for measuring state self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 895–910.

Holtzman, N. S. (n.d.). Did narcissism evolve? In A. D. Hermann, A. B. Brunell, & J. D. Foster (Eds.), The handbook of trait narcissism: Key advances, research methods, and controversies. New York: Springer.

Holtzman, N. S., & Strube, M. J. (2011). The intertwined evolution of narcissism and short-term mating. In W. K. Campbell & J. D. Miller (Eds.), The handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder: Theoretical approaches, empirical findings, and treatments (pp. 210–220). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Jonason, P. K., Li, N. P., Webster, G. D., & Schmitt, D. P. (2009). The dark triad: Facilitating a short-term mating strategy in men. European Journal of Personality, 23, 5–18.

Jonason, P. K., Valentine, K. A., Li, N. P., & Harbeson, C. L. (2011). Mate-selection and the dark triad: Facilitating a short-term mating strategy and creating a volatile environment. Personality and Individual Differences, 51, 759–763.

Jordan, C. H., Spencer, S. J., Zanna, M. P., Hoshino-Browne, E., & Correll, J. (2003). Secure and defensive high self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 969–978.

Jordan, C. H., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2013). Fragile self-esteem: The perils and pitfalls of (some) high self-esteem. In V. Zeigler-Hill (Ed.), Self-esteem (pp. 80–98). London: Psychology Press.

Kernberg, O. (1975). Borderline conditions and pathological narcissism. New York: Jason Aronson.

Kernis, M. H. (2003). Toward a conceptualization of optimal self-esteem. Psychological Inquiry, 14, 1–26.

Kernis, M. H. (2005). Measuring self-esteem in context: The importance of stability of self-esteem in psychological functioning. Journal of Personality, 73, 1569–1605.

Kohut, H. (1966). Forms and transformations of narcissism. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 14, 243–272.

Konrath, S., Bushman, B. J., & Grove, T. (2009). Seeing my world in a million little pieces: Narcissism, self-construal and cognitive-perceptual style. Journal of Personality, 77, 1197–1228.

Kuchynka, S. L., & Bosson, J. K. (2018). The psychodynamic mask model of narcissism: Where is it now? In A. D. Hermann, A. B. Brunell, & J. D. Foster (Eds.), The handbook of trait narcissism: Key advances, research methods, and controversies. New York: Springer.

Leary, M. R. (1999). Making sense of self-esteem. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 8, 32–35.

Leary, M. R., Cottrell, C. A., & Phillips, M. (2001). Deconfounding the effects of dominance and social acceptance on self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 898–909.

Leary, M. R., Haupt, A. L., Strausser, K. S., & Chokel, J. T. (1998). Calibrating the sociometer: The relationship between interpersonal appraisals and state self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1290–1299.

Leary, M. R., Tambor, E. S., Terdal, S. K., & Downs, D. L. (1995). Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: The sociometer hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 518–530.

Mahadevan, N., Gregg, A. P., Sedikides, C., & de Waal-Andrews, W. G. (2016). Winners, losers, insiders, and outsiders: Comparing hierometer and sociometer theories of self-regard. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1–19.

Maner, J. K., DeWall, N., Baumeister, R. F., & Schaller, M. (2007). Does social exclusion motivate interpersonal reconnection? Resolving the “porcupine problem”. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 42–55.

Morf, C. C., & Rhodewalt, F. (2001). Unraveling the paradoxes of narcissism: A dynamic self-regulatory processing model. Psychological Inquiry, 12, 177–196.

Murray, S. L., Rose, P., Bellavia, G. M., Holmes, J. G., & Kusche, A. G. (2002). When rejection stings: How self-esteem constrains relationship-enhancement processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 556–573.

Myers, E. M., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2012). How much do narcissists really like themselves? Using the bogus pipeline procedure to better understand the self-esteem of narcissists. Journal of Research in Personality, 46, 102–105.

Neiss, M. B., Sedikides, C., & Stevenson, J. (2002). Self-esteem: A behavioural genetic perspective. European Journal of Personality, 16, 351–367.

Pincus, A. L., Ansell, E. B., Pimentel, C. A., Cain, N. M., Wright, A., & Levy, K. N. (2009). Initial construction and validation of the pathological narcissism inventory. Psychological Assessment, 21, 365–379.

Raskin, R. N., & Hall, C. S. (1979). A narcissistic personality inventory. Psychological Reports, 45, 590.

Raskin, R. N., & Hall, C. S. (1981). The narcissistic personality inventory: Alternative form reliability and further evidence of construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 159–162.

Raskin, R. N., Novacek, J., & Hogan, R. (1991). Narcissism, self-esteem, and defensive self-enhancement. Journal of Personality, 59, 19–38.

Raskin, R. N., & Terry, H. (1988). A principle components analysis of the narcissistic personality inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 890–902.

Reise, S. P., & Wright, T. M. (1996). Personality traits, cluster B personality disorders, and sociosexuality. Journal of Research in Personality, 30, 128–136.

Rhodewalt, F., Madrian, J. C., & Cheney, S. (1998). Narcissism, self-knowledge organization, and emotional reactivity: The effect of daily experiences on self-esteem and affect. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24, 75–87.

Rhodewalt, F., & Morf, C. C. (1995). Self and interpersonal correlates of the narcissistic personality inventory: A review and new findings. Journal of Research in Personality, 29, 1–23.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Southard, A. C., Noser, A. E., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2014). Do narcissists really love themselves as much as it seems? The psychodynamic mask model of narcissistic self-worth. In A. Besser (Ed.), Handbook of the psychology of narcissism: Diverse perspectives (pp. 3–22). Hauppauge, NY: Nova.

Vernon, P. A., Villani, V. C., Vickers, L. C., & Harris, J. A. (2008). A behavioral genetic investigation of the dark triad and the big 5. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 445–452.

von Rueden, C., Gurven, M., & Kaplan, H. (2011). Why do men seek status? Fitness payoffs to dominance and prestige. Proceedings of the Biological Sciences, 278, 2223–2232.

Webster, G. D., Kirkpatrick, L. A., Nezlek, J. B., Smith, C. V., & Paddock, E. L. (2007). Different slopes for different folks: Self-esteem instability and gender as moderators of the relationship between self-esteem and attitudinal aggression. Self and Identity, 6, 74–94.

Williams, K. D., Cheung, C. K. T., & Choi, W. (2000). Cyberostracism: Effects of being ignored over the internet. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 748–762.

Zadro, L., Williams, K. D., & Richardson, R. (2004). How low can you go? Ostracism by a computer is sufficient to lower self-reported levels of belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaningful existence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 560–567.

Zeigler-Hill, V. (2006). Discrepancies between implicit and explicit self-esteem: Implications for narcissism and self-esteem instability. Journal of Personality, 74, 119–143.

Zeigler-Hill, V., & Besser, A. (2013). A glimpse behind the mask: Facets of narcissism and feelings of self-worth. Journal of Personality Assessment, 95, 249–260.

Zeigler-Hill, V., Chadha, S., & Osterman, L. (2008). Psychological defense and self-esteem instability: Is defense style associated with unstable self-esteem? Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 348–364.

Zeigler-Hill, V., Vrabel, J. K., McCabe, G. A., Cosby, C. A., Traeder, C. K., Hobbs, K. A., & Southard, A. C. (in press). Narcissism and the pursuit of status. Journal of Personality.

Zeigler-Hill, V., & Jordan, C. H. (2010). Two faces of self-esteem: Implicit and explicit forms of self-esteem. In B. Gawronski & B. K. Payne (Eds.), Handbook of implicit social cognition: Measurement, theory, and applications (pp. 392–407). New York: Guilford Press.

Zeigler-Hill, V., & Jordan, C. H. (2011). Behind the mask: Narcissism and implicit self-esteem. In W. K. Campbell & J. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder: Theoretical approaches, empirical findings, and treatment (pp. 101–115). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Zeigler-Hill, V., McCabe, G. A., Vrabel, J. K., Raby, C. M., & Cronin, S. (this volume). The narcissistic pursuit of status. In A. D. Hermann, A. B. Brunell, & J. D. Foster (Eds.), The handbook of trait narcissism: Key advances, research methods, and controversies. New York: Springer.

Zeigler-Hill, V., Myers, E. M., & Clark, C. B. (2010). Narcissism and self-esteem reactivity: The role of negative achievement events. Journal of Research in Personality, 44, 285–292.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Southard, A.C., Zeigler-Hill, V., Vrabel, J.K., McCabe, G.A. (2018). How Do Narcissists Really Feel About Themselves? The Complex Connections Between Narcissism and Self-Esteem. In: Hermann, A., Brunell, A., Foster, J. (eds) Handbook of Trait Narcissism. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92171-6_26

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92171-6_26

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-92170-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-92171-6

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)