Abstract

Social support is a key resource to predict job satisfaction. Yet little research has examined learned benefits in the process of receiving social support from work domain. Drawing from the role conflict and accumulation framework, we propose social support from domain can increase job satisfaction by (1) providing resources that can attenuate work-to-family conflict and (2) activating employees to learn from received support that can enhance work-to-family facilitation. To test the proposed theoretical model, we collected empirical data from 171 full-time employees in China. The empirical results partially supported our two mediator model. As predicted, social support increases job satisfaction through enhancing work-to-family facilitation. However, work-to-family conflict can not mediate the relationships between social support and job satisfaction. Contrasting effect analysis indicated the mediating effect of work-to-family conflict is significantly weaker than that of work-to-family facilitation between social support and job satisfaction. We discuss the implications for designing support systems in organizations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With the growing numbers of dissatisfied employees towards work in the past decades, scholars and managers are seeking effective ways to really help organizations (Kossek et al. 2011). In the review of work–family research, social support, defined as the perception that one is cared for, esteemed, and part of a mutually supportive social network (Taylor 2011), is seen as a pivot factor in organizations to improve employees’ job satisfaction (Adams et al. 1996; Ferguson et al. 2012).

One of prevalent perspectives is that organizations should provide sufficient family care (i.e., work–family policies). The organizational programs designed to assist employees’ family roles (e.g., parenting, elder care, education, and self-care) can greatly increase their commitments to organizations (Ryan and Kossek 2008). However, recent surveys report a significant decrease in the implementation of work–family policies (Shellenbarger 2008; Society for Human Resource Management 2010), meaning that organizational policies can not reach the expected outcomes. The major reason is the difficulties to effectively implement these support systems in organizations (Kossek et al. 2011).

In addition to the perspectives that focus on family care, we have noticed that social support associated with work-related affairs can also effectively increase employees’ job satisfaction. For instance, many studies show social support can stimulate employees to learn from received support and transfer learned skills and perspectives into family domain, thereby enhancing employees’ appreciation of their jobs (Greenhaus and Powell 2006; Haas 1999; McCauley et al. 1994). Therefore, reexamining the beneficial effects of social support from work domain and investigating the potential mechanisms on how this support improves job satisfaction can provide a novel and useful lens to better help organizations.

Drawing on the role conflict and accumulation framework (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985; Greenhaus and Powell 2006), we conclude that there are two beneficial effects of social support from work domain which can increase job satisfaction via work-to-family conflict and facilitation respectively. Work-to-family conflict represents the role conflict arising from the difficulty in participation in the family domain due to the demands of participation in the work domain (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985). While work-to-family facilitation describes the degree to which family role is made easier by the experience, skills, and opportunities employees gained or developed at work (Frone 2003).

To note, work–family interface is bidirectional and its dimensions have distinct impacts on the outcomes (Frone et al. 1997; Shockley and Singla 2011). According tosource attribution theory (Shockley and Singla 2011), work-to-family conflict and facilitation are expected more related to job satisfaction than family-to-work constructs be, because employees are more likely to blame the work role which causes work-to-family conflict and appreciate the sending role who produces benefits that enhance work-to-family facilitation. Meta-analysis also suggests affective consequences like job satisfaction are particularly consistent with source attribution theory (Amstad et al. 2011; Shockley and Singla 2011). We thus adopt work-to-family conflict and facilitation as two underlying mechanisms to investigate how social support from work domain affects job satisfaction.

We contribute to work–family research by providing new and useful lens to look at job satisfaction. Compared with adding extra resources which are costly to implement (e.g., work–family policies), we shed light on the necessity to optimize social support per se. We argue that utilizing support from work domain can reduce work-to-family conflict (Cheuk and Wong 1995; Cohen and Wills 1985; Eng et al. 2010). Importantly, we suggest that activating employees’ intrinsic motivation to learn from received support for work-to-family facilitation can also strenthen employees’ positive evaluation towards organizations.

Cultural norm plays a key role in the work–family relationships. We develop a culture-based hypothesis to compare different mediating effects of work-to-family conflict and facilitation and test the hypothesis with data from China, an area that has been understudied as a collectivist country. China in recent years has been the world’s most dynamic economy and is now undergoing an unprecedented economic transformation. This shift from a planned economy to a market-oriented economy accelerates the eradication of lifelong employment contracts which dominated in the past few decades (Joplin et al. 2003). On the one hand, the emerging job insecurity motivates men to get more involved in the work times and more social activities after work, leading to increased complaints from their spouses. On the other hand, women begin to seek job opportunities to earn more money for their extended families, resulting in more incompatibility between work and family roles. Unlike western countries, the culture factor such as Confucianism in China produces significantly different work–family perception and responses. Therefore, testing theories based on Western samples in Eastern countries can provide an excellent opportunity to add knowledge of the present theoriesFootnote 1.

Theory and Hypotheses

Mediating Effects of Work-to-Family Conflict

The role conflict and accumulation framework helps explain why social support from work domain increase job satisfaction via work-to-family conflict and facilitation. Role conflict assumes that individuals who participate in multiple roles (e.g., work and family) inevitably experience conflicts because of the limited resources (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985). While role accumulation states individuals experience in one role can produce positive outcomes in the other role (Greenhaus and Powell 2006).

We argue social support from work domain can reduce work-to-family conflict in the following ways. First, social support from work domain can provide the instrumental support that directly mitigates limited resources in coping with overly work demands. Because employees have limited resources to deal with work and family demands, role pressure arises when employees perceive insufficient time and energies to meet work demands. As a key resource, social support from work domain makes it easier for employees to fulfill work requirements by providing instrumental aids to attenuate the threat of work-to-family conflict. For example, social support related to work-related duties makes job responsibility clearer and allows employees to focus on effectively accomplishing organizational goals. Information assistance such as performance feedback and job experience facilitate communication between leaders and subordinates and strengthen problem-solving abilities in the work domain.

Second, emotional care as a form of social support from work domain cultivates employees’ positive affect (e.g., patience and confidence). Strain-based work-to-family conflict is a major type of pressure (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985). We demonstrate that supervisors’ emotional support such as encouragement and appreciation can fulfil the need for belongingness and attenuates the strain from work domain (Cohen and Wills 1985; Crawford et al. 2010). In addition, supervisors’ listening and discussing work-related problems suppress emotion-focused forms of coping and activate problem-focused coping strategies to deal with work demands (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Emotional care mitigates the feeling of tension, anxiety and fatigue and stimulates employees’ commitments to their organizations, thereby transferring less strain to family domain. Strong evidence from meta-analysis indicates social support from work domain has a negative relationship with work-to-family conflict (Byron 2005; Michel et al. 2011).

With reduced work-to-family conflict, social support from work domain increases job satisfaction, which represents overall evaluation on their jobs (Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller 2012). Due to fixed resources to manage multiple roles, work-to-family conflict occurs when work demands make family requirements difficult to be met. As described above, social support from work domain provides instrumental aids and emotional care to attenuate the time-based and strain-based conflict between work and family roles. When employees perceive organizational support can mitigate work pressure, they lessen their feelings of resentment and produce positive attitudes towards their jobs (Buonocore and Russo 2013). In line with this perspective, three meta-analyses on work–family interface supported the negative relationships between work-to-family conflict and job satisfaction (Allen et al. 2000; Shockley and Singla 2011; Amstad et al. 2011). We therefore hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 1. Work-to-family conflict mediates the positive relationship between social support from work domain and job satisfaction.

Mediating Effects of Work-to-Family Facilitation

The role accumulation perspective supposes that multiple roles can achieve positive outcomes in both work and family domains (Powell and Greenhaus 2010; Lazarova et al. 2010). That is, the useful social support employees have acquired in work domain (i.e., skills, behaviors, attitudes or positive mood) can increase the performance in family domain. Social support from work domain can strengthen work-to-family facilitation through two paths. First, support is expected to directly enhance the work-to-family facilitation. When employees learn skills and perspectives from supervisors’ guidance and apply them into family domain, they can use these resources to better balance work–family relationships and enhance managerial effectiveness in family domain. For example, the ability in dealing with complex jobs stimulate leadership skills development and thus enhance parenting at home (Haas 1999; McCauley et al. 1994).

Second, social support from work domain can stimulate positive affect that indirectly enhances work-to-family facilitation. When employees receive organizational resources, they generate positive affect which is supposed to be transferred into family domain, because employees perceive organizational support as an indication of the organization’s intent, viewing favorable or unfavorable treatment as a judgment of whether the organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being (Aselage and Eisenberger 2003). The caring, approval, and respect induced by social support from work domain fulfill employees’ socioemotional needs, leading to heightened positive mood in their work roles (Rhoades and Eisenberger 2002). A positive mood thus can suppress self-focused orientation, expand level of energy and motivate more proactive behaviors in the family domain (Rothbard 2001). In addition, the resilience and confidence learned from work enable employees to effective tackle with family chores.

Work-to-family facilitation can explain why social support from work domain increase job satisfaction. When skills and positive affect learned from work domain are applied into family domain, employees will attribute their increased efficiency in the family domain to the work domain which leads to job satisfaction (Baral and Bhargava 2010). This is consistent with reciprocity norm, employees who perceive organizational support benefits their family life will feel obligated to reciprocate toward the organization in the form of more favorable attitudes (Rhoades and Eisenberger 2002; Allen and Shanock 2013). In addition, meta-analysis showed work-to-family facilitation can positively predict job satisfaction (McNall et al. 2010). Formally, we hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 2. Work-to-family facilitation mediates the positive relationship between social support from work domain and job satisfaction.

Comparing the Mediating Effects of Work-to-Family Conflict and Facilitation

We argue the mediating effect of work-to-family conflict is weaker than work-to-family facilitation in Chinese contextFootnote 2. As mental programming which represents the patterns of thinking, feeling and acting, culture affects people’s perception and responses to work-to-family interface (Hofstede et al. 2010). We draw on the individualism-collectivism dimension to develop our hypothesis, because it plays an important role in treating work–family relationships (Yang et al. 2000). As defined by Hofstede et al. (2010), individualism pertains to societies where everyone is expected to care themselves, while collectivism pertains to societies in which people care and keep loyalty to their groups they belong to. Contrasting the Western countries, China is a collectivist country, whose Individualism Index Values ranked 58 among 76 Countries and Regions in Hofstede’s research (Hofstede et al. 2010). We suppose the mediating effect work-to-family conflict between social support from work domain and job satisfaction decreases, whereas the mediating effect of work-to-family facilitation increases in Chinese context.

First, we argue that employees less attribute work-to-family conflict to their jobs. Although job demands exacerbate work-to-family conflict, but they can meet their obligations for family requirements. The work in China is seen as self-sacrifices for the welfare of the family (Yang et al. 2000). Many Chinese employees even actively spend additional work hours to strive for family honor and prosperity (Redding and Wong 1986). Meanwhile, staying loyal to their organizations makes Chinese employees accept the reality of overly job demands (Hofstede et al. 2010). For example, Buonocore and Russo (2013) find that the affective commitment attenuates the negative relationship between work–family conflict and job satisfaction. Therefore, although social support from work domain reduces the conflict between work and family roles, employees will not increase expected changes of job satisfaction. We also find work in China is used for developing and maintaining interpersonal relationships (Hofstede et al. 2010). For example,. Chinese people tend to use guanxi to develop business and facilitate their family life. The benefits of expanding interpersonal relationships counteract the negative effect of work-to-family conflict, thereby decreasing the impact of work-to-family conflict on job satisfaction.

However, job satisfaction can greatly increase when received social support from work domain enhances work-to-family facilitation. As the resources learned from work domain, work-to-family facilitation can be seen as organizational benefits which can be used to increase family performance and stimulate employees’ feelings of appreciation by organizations. These recognition meets the needs of belongingness and strengthen employees’ identity as organizational members, which play key roles in collectivist countries (Hofstede et al. 2010). Thus, employees with increased work-to-family facilitation have stronger positive attitudes towards their job jobs. We therefore hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 3. the mediating effect of work-to-family conflict is weaker than that of work-to-family facilitation between social support from work domain and job satisfaction.

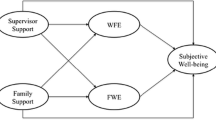

We conducted a multiple mediator model to examine the mediating roles of work-to-family conflict and facilitation between social support from domain and job satisfaction. Figure 1 presented our proposed theoretical model of the key theoretical relationships.

Methods

Research Design and Data Collection

Our study sample was derived from employees of 7 firms in China. Respondents are married or having a partner living together, with at least one child under the age of 21 living with them. We contacted the human resource departments of each firm to seek their participation, discussed the purposes of the study, and explained the procedures for implementing the survey. We coded the questionnaires with preassigned identification numbers and administered the pencil-and-paper questionnaires to employees by human resource departments. Completed questionnaires were returned to us via mail.

Out of 250 questionnaires distributed, 171 usable questionnaires were returned, with a response rate of 68.4 %. For this sample, 46.8 % of the respondents are male. Job type is labeled by “0” (non-managerial, e.g., production workers whose responsibilities are to process products such as assembling, testing or packaging) and “1” (managerial). 49.7 % of the respondents’ job type is managerial. The mean age of respondents is 38.95 years old (standard deviation = 5.16), and the average education year is 13.43 (standard deviation = 2.92). Ownership type is labeled by “0” (state-owned firm) and “1” (private firm) and 76 % of respondents work in state-owned firms.

Measures

Translation of Measurement Items

The measures were subjected to a double translation procedure. The questionnaire was translated to Chinese through double -translation to verify that the translation had a high degree of accuracy. A bilingual professor translated the original version of the questionnaire into Chinese and another professor and two doctoral students (all bilingual) translated the Chinese versions into English. The translated versions were compared for any possible inaccuracies. Minor translation issues were resolved among the four translators.

Social Support from Work Domain

We adopted four items developed by Antani and Ayman (2003) to measure social support from work domain (1 = never, 4 = frequently). In line with our proposed model which focused on how social support in the work domain could affect job satisfaction, this scale explicitly divided the social support into instrumental and emotional parts to access the work-related support. Two items assessed the instrumental support including “How often you receive support with respect to your work-related duties”;“How often you receive support with respect to helpful work-related information”. The other two items assessed the emotional support. These items were “How often you receive support in the form of listening to and discussing work-related problems”; “How often you receive support with respect to encouragement/appreciation regarding events in your work life”. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient is 0.88.

Work-to-Family Conflict

We used six items developed by Carlson et al. (2000) to measure work-to-family conflict with a six-point Likert scale anchored by “1” being “strongly disagree” and “6” being “strongly agree.” For example, the items include “My work keeps me from my family activities more than I would like,”; “When I get home from work I am often too physically tired to participate in family activities/responsibilities”; “I have to miss family activities due to the amount of time I must spend on work responsibilities”; “Due to all the pressures at work, sometimes when I come home I am too stressed to do the things I enjoy”; “The time I must devote to my job keeps me from participating in household responsibilities and activities”; and “I am often so emotionally drained when I get home from work that it prevents me from contributing to my family”. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient is 0.73.

Work-to-Family Facilitation

We adopted three items from Grzywacz and Marks (2000) to measure work-to-family facilitation. The items were composed of: “The things you do at work make you a more interesting person at home”; “Having a good day on your job makes you a better companion when you get home.” and “The skills you use on your job are useful for things you have to do at home”. Five-point Likert scale was used, anchored by “1” being “never” and “5” being “all of the time.” The Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient is 0.89.

Job Satisfaction

Two items from Hackman and Oldham (1975) were used. Respondents were asked to indicate their agreement to the items: “I am generally satisfied with the kind of work I do in my present job” and “Generally speaking, I am very satisfied with my present job” with a six point Likert scale anchored by “1” being “strongly disagree” and “6” being “strongly agree”. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient is 0.86.

Control Variables

We included gender, age, education, job type and ownership type as control variables. These variables are correlated with work and family demands and relate to work-to-family conflict and work-to-family facilitation, and have been used in other studies as control variables (Hoobler et al. 2009).

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA)

Before testing the hypotheses, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to demonstrate discriminant validity among our four theoretical variables: social support from work domain, work-to-family conflict, work-to-family facilitation and job satisfaction. We used the commonly accepted cutoff values (comparative fit index [CFI] > 0.90, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] < 0.08, standardized root mean squared residual [SRMR] < 0.09) for determining good fit (Kraimer et al. 2012). We then compared our hypothesized four-factor model to alternative nested models using the chi-square difference test to determine the best-fitting model. The CFA results suggested that the hypothesized four-factor model (CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.05) yielded a better fit than all models in which one or more covariances was set equal to one (Δdf = 1 to 3; Δχ2 = 137.27 to 210.11, p < 0.001 in all cases), providing support for the measurement model (see Table 1).

To assess the extent to which common method variance (CMV) was a concern, we used Harman’s single-factor test, which combines all items from all of the constructs into one factor analysis to determine whether the majority of the variance can be accounted for by a general factor (Podsakoff et al. 2003). The results show that the methods factor explained 23.20 percent of the variance, a level well below the 0.50 cutoff that was suggested as indicating the presence of a single substantive factor (Hair et al. 1998). These results therefore suggest that CMV was not a significant biasing source of the variability in our theoretical variables. Table 2 presents descriptive statistics.

Hypothesis Testing

We followed procedures suggested by Baron and Kenny (1986) to test the multiple mediator model. As recommended by Preacher and Hayes (2008), we performed bootstrapping method to test the indirect and contrasting effects of work-to-family conflict and facilitation between social support from work domain and job satisfaction.

Following Baron and Kenny (1986), we first regressed job satisfaction on social support from work domain and the control variables. The results presented in Table 3 (Model 4) indicated that there was a significant and positive relationship between social support from work domain and job satisfaction (β = 0.17, p < 0.05). In the second step, work-to-family conflict and facilitation were respectively regressed on the control variables and social support from work domain (Model 1 and Model 2). The results showed that social support from work domain was significantly and negatively related to work-to-family conflict (β = −0.17, p < 0.05) and significantly and positively related to work-to-family facilitation (β = 0.22, p < 0.01).

To reduce parameter bias owing to omitted variables (Judd and Kenny 1981), we simultaneously entered work-to-family conflict and facilitation in a single regression in the third step. The results (Model 5) indicated that work-to-family facilitation had a significant and positive relationship with job satisfaction (β = 0.30, p < 0.01). However, the impact of work-to-family conflict on job satisfaction was not significant (β = − 0.04, p > 0.1). Then job satisfaction was regressed on social support from work domain, work-to-family conflict and facilitation and the control variables in the last step. The results (Model 6) indicated that the significant relationship between social support from work domain and job satisfaction became nonsignificant when the work-to-family conflict and facilitation were entered into the equation (β = 0.10, p > 0.1). Work-to-family conflict was not significantly related to job satisfaction (β = − 0.03, p > 0.1), whereas work-to-family facilitation was significantly related to job satisfaction (β = 0.28, p < 0.01).

To test indirect effect of work-to-family conflict and facilitation between social support from work domain and job satisfaction, we followed bootstrap sampling method recommended by Preacher and Hayes (2008), which avoid problems of nonnormal sampling distributions that arise when computing products of coefficient tests (MacKinnon et al. 2004). We performed the bootstrap sampling method (bootstrap sample size =5000) to generate asymmetric confidence intervals for the product of coefficients and obtain a more accurate estimation of the indirect relationship. If the 95 % confidence interval for the parameter estimate do not contain zero, then the effect is statistically significant. The results reported in Table 4 indicated the indirect effect of work-to-family conflict between social support from work domain and job satisfaction was not significant, with the 95 % confidence intervals being (−0.03, 0.07), containing zero. Thus Hypothesis 1 was not supported. The bootstrapping test showed the indirect of social support from work domain on job satisfaction is significant through work-to-family facilitation. The 95 % confidence intervals were (0.02, 0.20), excluding zero. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Hypothesis 3 proposes the mediating effect of work-to-family conflict is weaker than the mediating effect work-to-family facilitation between social support from work domain. We also performed bootstrapping to generate asymmetric confidence intervals for difference between these two indirect effects by using the macro for SPSS recommended by Preacher and Hayes (2008). In this case, the difference was estimated by using the indirect effect through work-to-family conflict minus specific indirect effect through work-to-family facilitation. The results indicated the difference was significant with the 95 % confidence intervals being (−0.20, −0.01), excluding zero. Meanwhile, the results showed the indirect effects through work-to-family conflict and facilitation were of the same sign, thus Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Discussion

This study extends work–family research by examining the impacts of social support from work domain on job satisfaction via work-to-family interface. In line with the stress relief view (Viswesvaran et al. 1999; Hauck et al. 2008; Cheuk and Wong 1995; Michel et al. 2010), our study shows social support from work domain can directly attenuate work-to-family conflict. As defined by Lazarus and Folkman (1984), a stress experience occurs when there is a discrepancy between demands and the availability of resources. Social support as key resources can eliminate the discrepancy by providing instrumental and emotional aids to reduce role pressure incompatibility between work and family domain, thereby reducing stress experience and burnout. However, the nonsignificant indirect effect of work-to-family conflict between social support from work domain and job satisfaction indicated that decreased work-to-family conflict can not increase job satisfaction. Although this is counter-intuitive, it is consistent with Spector et al. (2007), whose cross-cultural research showed the similar weak relationships between work-to-family conflict and job satisfaction. They demonstrate that employees in the collectivistic society might be more likely to keep loyalty to their organizations and respond this work demands with greater affiliation.

Our empirical results give evidences that social support from work domain increase job satisfaction through work-to-family facilitation. That is, employees who use learned skills and positive affect to facilitate family performance can enhance their appreciation on jobs. For instance, positive affect arising from accomplishment and gratification in the work domain can transfer to family dynamics, contributing to a more satisfying performance in family domain. Guided by norm of reciprocity, perceiving organization’s help in managing work and family roles, will produce positive feelings on their organizations (Wayne et al. 2006; McNall et al. 2009).

Although previous studies have showed that work–family balance is a potential mechanism to predict outcomes (Jeffrey H. Greenhaus et al. 2003; Ferguson et al. 2012), our study can strengthen our understanding of work–family relationships in the cultural context. Because different culture engenders different work and family identities which produce different evaluations of work–family balance (Kossek et al. 2011). For example, some employees work 80 h a week perceive work–family balance, but others feel work–family balance only when their work time limits to 40 h per week (Kossek et al. 2011). Our comparison between the mediating effects of work-to-family conflict and facilitation indicates that work-to-family facilitation plays major mediating role between social support from work domain and job satisfaction in Chinese context, i.e., the nature of collectivism stimulates Chinese employees less attribute work-to-family conflict.

From the practical standpoint, our study provides new perspectives on support systems in organizations. We recommend that organizations should provide the supports which focus on teaching someone to do something than to do it for them. Our findings indicate employees will appreciate their jobs if support from domain benefits their family life. If skills and perspectives are learned and applied to strengthen their family performance, job satisfaction can greatly increase. Thus, organization should provide sufficient support programs (e.g., training programs) which can facilitate employees to learn from receiving support. This is consistent with Chinese proverbs which state, “give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.” We also suggest organizations in China to offer more emotional care. Due to the strong needs of belongingness in organizations, emotional support thus is particularly effective to active employees’ positive affect. When the positive affect results from caring, approval, and respect is transferred into family domain, Chinese employees will increase their tendency to reciprocate their organizations.

This research has several limitations that can be addressed in future research. First, we cannot draw firm conclusions about causation in this study by using cross-sectional data. We heavily rely on the assumptions of the role conflict and accumulation framework in hypothesizing the causal relationships and interpreting the empirical findings. Accordingly, we cannot rule out the possibility of reverse causation. That is, it is possible that job satisfaction might affect work-to-family conflict and facilitation. Conducting longitudinal research can provide more conclusive evidence of causality concerning the directionality of the hypothesized relationships in our model. Second, we only investigated the effects of social support from work domain. Based on source attribution hypothesis (Shockley and Singla 2011), stating individuals are prone to attribute benefits and blame to the domain that produces the conflict and facilitation, we explained how support from work affects on job attitudes through work-to-family facilitation. However, recent research has indicated support from family domain is also an important source of work–family balance (Ferguson et al. 2012). Future research can integrate both work and family support to investigate its beneficial effects and outcomes in multicultural context.

Notes

The authors thank anonymous reviewers for this suggestion.

The authors thank anonymous reviewers for this suggestion.

References

Adams, G. A., King, L. A., & King, D. W. (1996). Relationships of job and family involvement, family social support, and work-family conflict with job and life satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(4), 411–420.

Allen, D. G., & Shanock, L. R. (2013). Perceived organizational support and embeddedness as key mechanisms connecting socialization tactics to commitment and turnover among new employees. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(3), 350–369.

Allen, T. D., Herst, D. E. L., Bruck, C. S., & Sutton, M. (2000). Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(2), 278–308.

Amstad, F. T., Meier, L. L., Fasel, U., Elfering, A., & Semmer, N. K. (2011). A meta-analysis of work-family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(2), 151–169.

Antani, A., & Ayman, R. (2003). Gender, social support and the experience of work-family conflict. Paper presented at the European Academy of Management, Milan, Italy

Aselage, J., & Eisenberger, R. (2003). Perceived organizational support and psychological contracts: A theoretical integration. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24(5), 491–509.

Baral, R., & Bhargava, S. (2010). Work-family enrichment as a mediator between organizational interventions for work-life balance and job outcomes. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(3), 274–300.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Buonocore, F., & Russo, M. (2013). Reducing the effects of work-family conflict on job satisfaction: The kind of commitment matters. Human Resource Management Journal, 23(1), 91–108.

Byron, K. (2005). A meta-analytic review of work–family conflict and its antecedents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 169–198.

Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., & Williams, L. J. (2000). Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of work-family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56(2), 249–276.

Cheuk, W. H., & Wong, K. S. (1995). Stress, social support, and teacher burnout in macau. Current Psychology, 14(1), 42–46.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357.

Crawford, E. R., Lepine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 834–848.

Eng, W., Moore, S., Grunberg, L., Greenberg, E., & Sikora, P. (2010). What influences work-family conflict? The function of work support and working from home. Current Psychology, 29(2), 104–120.

Ferguson, M., Carlson, D., Zivnuska, S., & Whitten, D. (2012). Support at work and home: The path to satisfaction through balance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(2), 299–307.

Frone, M. R. (2003). Work-family balance. In J. C. Quick & L. E. Tetrick (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (pp. 143–162). Washington: American Psychological Association.

Frone, M. R., Yardley, J. K., & Markel, K. S. (1997). Developing and testing an integrative model of the work-family interface. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50(2), 145–167.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 72–92.

Greenhaus, J. H., Collins, K. M., & Shaw, J. D. (2003). The relation between work–family balance and quality of life. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63(3), 510–531.

Grzywacz, J. G., & Marks, N. F. (2000). Reconceptualizing the work–family interface: An ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 111–126.

Haas, L. (1999). Families and work. In Handbook of marriage and the family (pp. 571–612): Springer.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1975). Development of the job diagnostic survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(2), 122–122.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Hauck, E. L., Snyder, L. A., & Cox-Fuenzalida, L.-E. (2008). Workload variability and social support: Effects on stress and performance. Current Psychology, 27(2), 112–125.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: McGraw

Hoobler, J. M., Wayne, S. J., & Lemmon, G. (2009). Bosses’ perceptions of family-work conflict and women’s promotability: Glass ceiling effects. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 937–957.

Joplin, J. R. W., Shaffer, M. A., Francesco, A. M., & Lau, T. (2003). The macro-environment and work-family conflict development of a cross cultural comparative framework. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 3(3), 305–328.

Judd, C. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1981). Process analysis estimating mediation in treatment evaluations. Evaluation Review, 5(5), 602–619.

Judge, T. A., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. (2012). Job attitudes. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 341–367.

Kossek, E. E., Baltes, B. B., & Matthews, R. A. (2011). How work–family research can finally have an impact in organizations. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 4(3), 352–369.

Kraimer, M. L., Shaffer, M. A., Harrison, D. A., & Ren, H. (2012). No place like home? An identity strain perspective on repatriate turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 55(2), 399–420.

Lazarova, M., Westman, M., & Shaffer, M. A. (2010). Elucidating the positive side of the work-family interface on international assignments: A model of expatriate work and family performance. Academy of Management Review, 35(1), 93–117.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company LLC.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128.

Management, S. f. H. R. (2010). 2010 employee benefits: Examining employee benefits in the midst of a recovering economy (Alexandria): VA: Author.

McCauley, C. D., Ruderman, M. N., Ohlott, P. J., & Morrow, J. E. (1994). Assessing the developmental components of managerial jobs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(4), 544–560.

McNall, L. A., Masuda, A. D., & Nicklin, J. M. (2009). Flexible work arrangements, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions: The mediating role of work-to-family enrichment. Journal of Psychology, 144(1), 61–81.

McNall, L. A., Nicklin, J. M., & Masuda, A. D. (2010). A meta-analytic review of the consequences associated with work–family enrichment. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(3), 381–396.

Michel, J. S., Mitchelson, J. K., Pichler, S., & Cullen, K. L. (2010). Clarifying relationships among work and family social support, stressors, and work–family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76(1), 91–104.

Michel, J. S., Kotrba, L. M., Mitchelson, J. K., Clark, M. A., & Baltes, B. B. (2011). Antecedents of work-family conflict: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(5), 689–725.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Powell, G. N., & Greenhaus, J. H. (2010). Sex, gender, and the work-to-family interface: Exploring negative and positive interdependencies. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 513–534.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

Redding, G., & Wong, G. Y. Y. (1986). The psychology of chinese organizational behaviour. In M. H. Bond (Ed.), The psychology of the chinese people (pp. 267–295). New York: Oxford University Press.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698–714.

Rothbard, N. P. (2001). Enriching or depleting? The dynamics of engagement in work and family roles. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(4), 655–684.

Ryan, A. M., & Kossek, E. E. (2008). Work-life policy implementation: Breaking down or creating barriers to inclusiveness? Human Resource Management, 47(2), 295–310.

Shellenbarger, S. (2008). Downsizing maternity leave: Employers cut pay, time off. Wall Street Journal, D1

Shockley, K. M., & Singla, N. (2011). Reconsidering work–family interactions and satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 37(3), 861–886.

Spector, P. E., Allen, T. D., Poelmans, S. A. Y., Lapierre, L. M., Cooper, C. L., Michael, O. D., et al. (2007). Cross-national differences in relationships of work demands, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions with work-family conflict. Personnel Psychology, 60(4), 805–835.

Taylor, S. E. (2011). Social support: A review. In H. E. Friedman (Ed.), The oxford handbook of health psychology (pp. 189–214). New York: Oxford University Press.

Viswesvaran, C., Sanchez, J. I., & Fisher, J. (1999). The role of social support in the process of work stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54(2), 314–334.

Wayne, J. H., Randel, A. E., & Stevens, J. (2006). The role of identity and work-family support in work-family enrichment and its work-related consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69(3), 445–461.

Yang, N., Chen, C. C., Choi, J., & Zou, Y. (2000). Sources of work-family conflict: A sino-us comparison of the effects of work and family demands. Academy of Management Journal, 43(1), 113–123.

Acknowledgments

Research support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71472,054, 71102130) is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Lin, Y. & Wan, F. Social Support and Job Satisfaction: Elaborating the Mediating Role of Work-Family Interface. Curr Psychol 34, 781–790 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-014-9290-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-014-9290-x