Abstract

Refugees’ employment is considered one of the most important indicators of self-sufficiency in the new country in which they resettle. Previous literature examined several factors that were associated with refugee employment, but most studies focused on refugees’ sociodemographic characteristics. Hypothesizing that various resources available to refugees after arrival can impact their employment outcomes, this study examined the influence of both the pre- and post-migration factors. The national-level 2019 Annual Survey of Refugees (ASR) data and logistic regression based on 2,031 individuals were used to examine the inquiry. The results showed that while pre-migration factors such as gender and prior work experience mattered, post-migration factors such as job training and English proficiency also showed strong associations for refugees’ work experiences in the U.S. Conversely, welfare assistance did not show positive associations. This study motivates future research into the efficacy of resettlement support and welfare benefits, as well as on the meaning of job and self-sufficiency among refugees.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The number of refugees is growing at a faster rate than ever before. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR, hereinafter) (UNHCR, 2023a), 108.4 million individuals were forcibly displaced worldwide because of persecution, conflict, violence, or human rights violation by the end of 2022. The current political instability and climate change are predicted to continue with an upward trajectory. Commonly referred to as the refugee crisis, how such a large number of refugees can resettle and receive support across national borders remains a critical agenda.

This reality is no different in the United States (U.S., hereinafter). Although the U.S. refugee resettlement has fluctuated over the past decade reflecting the priority of presidential administrations (Ward & Batalova, 2023), the current administration recognizes the global displacement crisis unprecedented and raised the admission ceiling highest in several decades (U.S. Department of State, 2023). The U.S. received approximately 25,400 refugees and 36,615 asylees in 2022, which is double the previous year (Gibson, 2023).

When refugees arrive in a new country, one of the key areas that help refugees is economic inclusion (UNHCR, 2023b). The opportunity to work and earn a living is considered one of the most effective ways to start new lives with dignity, overcome poverty, and be socially integrated (Bloch, 2007; Khawaja & Hebbani, 2018). In the U.S., refugees receive immediate assistance for resettlement and other welfare benefits to be economically independent in the long run.

Getting a job, however, comes with various challenges. With a drastic change in life, refugees typically lose access to their former resources and face limited opportunities in a new environment (Freudenberg & Halberstadt, 2018). Refugees are severely disadvantaged in the local market compared to the native population due to factors such as a lack of language skills, limited social networks, cultural differences, career interruptions, undervalued previous work experiences, uncertain legal status, and social discrimination (Baranik et al., 2018; Battisti et al., 2019; Boss et al., 2022; Jackson & Bauder, 2014). It is also known that refugees are pressured to settle for low-skilled and low-paid jobs to qualify for welfare eligibility as well as to work in an environment that obstructs their social integration into mainstream society (Colic-Peisker & Tilbury, 2006; Jackson & Bauder, 2014; Lumley-Sapanski, 2021; Shutes, 2011).

Previous literature examined the type of factors that were important for refugees’ job outcomes but mostly focused on refugees’ individual sociodemographic characteristics without taking the post-migration resettlement factors into account (e.g., Baranik, 2021; Khawaja & Hebbani, 2018; Renner & Senft, 2013). Individuals who arrive in the U.S. with refugee status are placed in a specific city and connected with a local resettlement agency that delivers services upon arrival. While the federal refugee resettlement program and assistance serve as a common foundation, refugees’ individual resettlement experiences can vary based on the approach, value, and quality of services provided by local service providers (Shaffer et al., 2020; Singer & Wilson, 2006). Considering this local variability, we argue that it would be beneficial to consider refugees’ characteristics both before and after the migration. The current study examines the impact of both the pre- and post-migration factors, particularly focusing on various resettlement support provided for refugee populations such as job training and welfare programs.

This article is structured as follows. We first discuss the significance of employment within the frameworks of refugee resettlement and integration. Then, we will delve into the U.S. refugee resettlement policy which will inform our understanding of refugee self-sufficiency, accompanied by relevant literature on the factors associated with refugee employment. Following this, we will describe the methods, present the results, and engage in a discussion of the study.

Refugee Resettlement and Employment in the U.S.

Among others, employment has been conceptualized as a core component of refugees’ integration into the native society. According to the 10 core domains of integration proposed by Ager and Strang (2008), employment is one of the key factors for integration along with other ones such as housing, education, and health. In the recent conceptualization of integration, Ortlieb and Knappert (2023) also suggested that finding employment and being included in the workplace are the two last important stages of integration.

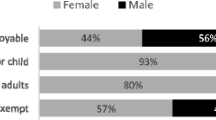

In fact, the emphasis on employment stands prominent in the context of U.S. policy. The Refugee Act of 1980 articulates that the primary purpose of the U.S. refugee resettlement programs is to support refugees to achieve self-sufficiency as quickly as possible after arrival (Refugee Act, 1980). The aid includes cash assistance such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF, hereinafter), Refugee Cash Assistance (RCA, hereinafter), Supplementary Security Income (SSI, hereinafter), and General Assistance (GA, hereinafter) as well as non-cash assistance such as the Supplement Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, hereinafter) and public housing. Figure 1 shows the overall structure of resettlement assistance, divided by cash and non-cash assistance types.

Although self-sufficiency can mean both social and economic capabilities, refugee-serving organizations often consider self-sufficiency as refugees’ financial capability to live independently from humanitarian assistance (Shalan, 2019). The Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR, hereinafter) also regards refugees as self-sufficient when they earn enough income to support themselves without cash assistance even when they receive other types of non-cash assistance such as SNAP or Medicaid (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2012). Therefore, most of the resettlement programs promote rapid employment for refugees so that they can wean from welfare (Chen & Hulsbrink, 2019). In fact, the time frame for welfare assistance and pressure to find work go hand in hand. While most refugees are entitled to four to eight months of federal cash assistance (Tran & Lara-García, 2020), refugees are expected to become financially independent within their first six to eight months in the U.S. (Kreisberg et al., 2022).

The literature in the U.S. often focuses on how quickly refugees are able to find their job and how much they rely on welfare benefits beyond initial settlement support (Kallick & Mathema, 2016; Stempel & Alemi, 2021). The conceptualization of self-sufficiency as economic independence, however, has been critiqued as it does not provide a holistic picture of successful resettlement. On a macro level, it ignores other sociocultural and political factors that would influence refugees’ integration (Chen & Hulsbrink, 2019; Shalan, 2019). A heavy emphasis on employment outcomes also places the burden of integration solely on refugees when refugee integration is in fact a multi-faceted, two-way process between the host society and the newly arrived individuals (Bottero, 2023; Klarenbeek, 2021). The host society often expects and imposes the value of unity and a consensual view of society, the frameworks from which refugee success would then be judged based on their individual-level traits, whether being well integrated or less integrated than others (Favell, 2022; Rytter, 2019; Schinkel, 2018). However, it would present a biased and incomplete perspective on integration if we fail to consider the role and responsibilities of the receiving society.

Even on a micro level, whether someone can be defined as self-sufficient within six months of arrival is debatable. Some of the refugee-serving providers in New York City challenged the time frame and argued that refugees are not given sufficient time to deal with cultural shock, language barriers, and trauma (Zubaroglu-Ioannides & Yalim, 2022). In this regard, self-sufficiency as time-bounded job hunting often becomes the goal of refugee resettlement agencies that need to prove their performance, not of refugees themselves (Benson & Panaggio, 2019; Darrow, 2018).

The strong emphasis on work has also been critiqued in light of welfare policies. Economic measures of integration solely on employment rates or income levels do not offer comprehensive metrics of long-term success, such as civic and political participation (Fix et al., 2017). Benson (2016) pointed out that refugee resettlement policy has not been an exception to the neoliberal policy environment that promotes market-based approaches and strategies for poverty governance. Under this framework, refugees’ welfare dependence is problematized, and thus, refugees are pressured to work and become productive citizens as soon as possible. Whether such pressure leads to worthy outcomes, however, has been questioned.

Refugees typically accept the first available job which is often low-wage, or any job, to qualify for workfare (Benson, 2016; Chen & Hulsbrink, 2019; Yako & Biswas, 2014). As a result, refugees often take entry-level, low-skilled, or unskilled manual labor positions, so-called survival jobs, that are pre-identified by the refugee resettlement agencies (Bloch, 2007; Bridekirk & Hynie, 2021; Colic-Peisker & Tilbury, 2006; Lumley-Sapanski, 2021; Shutes, 2011). These jobs, potentially resulting in “underemployment” (Disney & McPherson, 2020), may enable the refugees initially to discontinue welfare use, but it generates negative implications for their wages and job quality in the long run, particularly for refugees with less human capital (Lumley-Sapanski, 2021).

To identify contributing factors to refugee employment, research has examined the association between a variety of socioeconomic characteristics of refugees and their employment statuses. Gender, country of origin, education attainment, length of stay in the U.S., and language skills have been popular measures that were tested: typically, being a male, having higher levels of education, and English proficiency were found to be important factors for obtaining employment (e.g., LoPalo, 2019; Lumley-Sapanski, 2021; Potocky-Tripodi, 2001; Race & Masini, 1996). In addition, qualitative studies added insights into the barriers that refugees experience during the job searching process such as childcare responsibilities, time limits, social discrimination, devaluation of previous work experiences, and ineffectiveness of job search assistance programs (e.g., Baranik et al., 2018; Battisti et al., 2019; Benson & Panaggio, 2019; Shutes, 2011; Vromans et al., 2018).

Some studies examined the effects of post-migration support on refugees’ employment. For example, LoPalo (2019) examined the effects of direct welfare benefits such as TANF and found that amount of cash benefits was associated with higher wages, especially for the highly educated, but it did not impact the probability of employment. On the other hand, non-welfare resources such as job training and English training were also found to be helpful for refugees’ employment outcomes (Tran & Lara-García, 2020).

Based on what has been discovered regarding refugee employment outcomes, previous research pointed out that little discussion has been held on the impact of policies on helping refugees make successful adjustments (Tran & Lara-García, 2020). Instead, migration literature has mostly focused on pre-migration factors such as refugees’ demographic characteristics, human capital, or individual networks for finding employment (Kreisberg et al., 2022). To fill the gap in knowledge, we examined the relationship between post-migration resettlement programs and employment outcomes along with other individual factors using nationally representative data.

Data and Methods

Dataset

The 2019 Annual Survey of Refugees (ASR, hereinafter) data were used. The ASR data have been collected by the ORR annually since the early 1980s, with the purpose of understanding refugees’ integration progress during the early years of resettlement as well as fulling its requirement to submit congressionally mandated reports following the Refugee Act of 1980 (ORR, 2022a). ASR has a unique strength as a dataset because it is the only nationally representative data that represents refugees from 114 countries (ORR, 2022a). The variables included in the dataset also provide key information on refugees’ progress toward self-sufficiency, including the aspects of English proficiency and job acquirement.

The 2019 ASR is based on interviews conducted in early 2020 with refugees who entered the U.S. between 2014 and 2018. The ASR dataset does not identify respondents’ current legal status. However, based on questions regarding “whether they had applied to adjust their legal status to permanent residency” or “what the primary reason was for moving to this state,” we can infer that the ASR dataset includes refugees in various legal statues and social situations, including not only those who applied for refugee status outside the U.S. and were screened before their arrival, but also those who submitted their applications in the U.S. as asylum seekers. Therefore, although they may have experienced different admission processes and agencies responsible for reviewing their applications (Ward & Batalova, 2023), refugees and asylum seekers (or asylees) do not seem to be considered separately in this study.

The original 2019 ASR included information on 1,506 households and 4,905 individuals. However, because the primary focus of this study is on people’s employment, we narrowed our sample to the working-age populations (18–64 years old). After narrowing down the sample, the dataset yielded 1,460 households and 2,998 observations. Due to missing observations as well as uninformative responses such as “refused to answer” or “don’t know,” the final sample size decreased to 2,031.

Some of the variables had more missing observations than others. For example, while age and household characteristics did not have any missing values, other variables had missing values, with the number varying between 1 and 571. Demographic variables had a low number of missing observations, such as gender (n = 1) and country of birth (n = 5). The variable that had the largest missing observations was related to education (n = 452 and n = 571, before and after coming to the U.S., respectively). Job-related variables also had relatively high missing observations (n = 409 for pre-migration work experience, n = 397 for post-migration job training). The magnitude of missing observations on welfare variables was mixed: while the variables on cash and non-cash assistance showed close to full observations (missing 20 and 6 observations, respectively), the variable on medical support had 463 missing observations.

We performed t-tests to compare the sample characteristics before and after removing the missing observations to examine how the removal of these cases might be affecting the sample and results. The results revealed that the final sample included people with more education before coming to the U.S. (9.56 years in the final sample vs. 9.07 years in the previous sample, p = 0.04), more pursuit of higher education degrees after coming to the U.S. (0.41 vs. 0.28, p = 0.02), and more pre-migration and post-migration work experience (0.50 vs. 0.43, p = 0.01, and 0.62 vs. 0.57, p = 0.04, respectively). Given that the most missing data occurred for the education and work variables, it is plausible to conjecture that individuals without education or work backgrounds may not have fully answered those questions, skewing the final sample toward individuals with more education and work experience.

Variables

The outcome variable was the refugees’ work experience in the U.S. Individuals were considered “having work experience” if they reported working at a job at the time of survey or if they said they are not working now but they previously worked in the U.S. These responses were differentiated from those who responded that they were not working now and never worked in the U.S. We posit that these two groups may embody different attitudes, values, or physical or social conditions that either motivate or hinder employment, and thus, it became our primary interest.

The ASR data include questions that provide a more contextualized understanding of refugees’ working conditions, such as the number of worked hours and the type of industry in which refugees were employed. The final data suggests that close to 70% of the respondents who answered the question worked 40 hours or more per week. However, our outcome variable remained whether someone has had work experience or not, rather than focusing on the specific working conditions. We concluded that the type of questions available in the ASR data (e.g., number of hours worked) does not provide comprehensive insights into refugees’ working conditions. For instance, refugees working 80 hours a week may not necessarily indicate a more stable job situation compared to those working 40 hours a week. It was also challenging to determine the critical difference between those who work 40 hours compared to those who work 35 hours, and whether working 40 hours and more would imply better employee benefits. Therefore, we conceptualized that refugees who are not currently employed and have never worked in the U.S. after several years of resettlement would offer a more distinct indication of individuals who are either unable or unwilling to engage promptly in the workforce, thereby serving as a compelling category. The outcome variable was coded as binary to differentiate between individuals with prior experience (Yes = 1) and those without (No = 0). The type of industry in which refugees are working is summarized in Table 1. Although there was no predominant category, manufacturing, retail, and hospitality were the top three industries in which refugees were employed, closely followed by general products and transportation.

Independent variables consisted of factors potentially influencing the job outcomes of refugees. Demographic variables known to have a significant influence on job outcomes, such as age, gender, household characteristics, and country of origin, were taken into consideration (Bloch, 2007; Khawaja & Hebbani, 2018). Age was considered as a continuous variable. Gender was coded as a binary variable (Male = 1, Female = 0) following the two categories used in the original survey question (i.e., Is (INSERT NAME) male or female?). Both males and females were almost equally represented in our sample.

Country of birth was included as a dummy variable, with the largest group, Iraq, as the reference group. The final data included 13 distinctive categories, including Afghanistan, Bhutan, Burma (also known as Myanmar), Cuba, Congo, El Salvador, Iran, Iraq, Nepal, Somalia, Syria, Ukraine, and other. These were the categories created by and adopted from the ASR data. As mentioned in the sample section above, we lack information on these groups’ migration paths. However, these nationalities represent those with higher refugee and asylum applications in the U.S. (Ward & Batalova, 2023). We included country of birth as a proxy for the unique culture associated with each country and ethnic group. Previous research suggests that culture can influence gender roles, education level, and value placed on work, which in turn can influence people’s decisions to work (e.g., Baranik, 2021; Due et al., 2021; Salikutluk & Menke, 2021; Stempel & Alemi, 2021; Wimpelmann, 2017).

Household composition was considered in the form of a binary variable: 1 for multiple-people households and 0 for single-person households. The presence of multiple people in households was used as a proxy to hypothesize that individuals in these households may be more motivated to work due to family responsibilities, regardless of for whom they serve caretaking roles (Potocky-Tripodi, 2001). Moreover, given that refugee families from certain cultures can have larger and more multi-generational structures (Potocky & Naseh, 2019; Potocky-Tripodi, 2001), it is plausible that family responsibilities are not limited to childcare. In fact, the ASR data did not ask respondents whether they had children. Rather, they asked who was living in the household. In the multiple-person household, the household composition varies, not only married partners, but also non-married partners, siblings, parents, in-laws, children, relatives, non-relatives, and others. A little over 90% of the sample comprised multiple-person households.

Refugees’ duration of stay in the U.S. was considered in our study in the form of the number of years since their arrival. Previous research suggests that refugees can use work to integrate into mainstream society while their employment outcome may vary over time in the host country (Chiswick & Miller, 2011). Time in the U.S. was almost evenly distributed across the five groups: two years (20.6%), three years (18.9%), four years (23.1%), five years (17.1%), and six years (20.3%).

Both the educational level before and after coming to the U.S. were considered continuous variables. The survey asked, “How many years of schooling did this person complete before coming to the U.S.,” and the response ranged between 0 and 20. Each number represents the number of years of education, with 20 representing 20 years and more. Respondents’ pursuit of education after coming to the U.S. was based on the response to the question, “Within the past 12 months, has this person attended school or university?” The survey responses were coded as a continuous variable in four levels: a high school diploma = 1, an associate degree = 2, a Bachelor’s degree = 3, a Master’s or Doctorate, professional school degree (e.g., MD, LLB, and DDS), or certificate/licensure = 4. This question focused on the pursuit of academic degrees, which was distinguished from English training or job training that was asked in other sections in the survey.

English proficiency before and after coming to the U.S. were asked in two questions, “At the time of arrival in the U.S., how well did (INSERT NAME) speak English?” and “How well does (INSERT NAME) speak English now?” These responses were coded on a scale of 4 (Not at all = 1, Not well = 2, Well = 3, Very well = 4). English proficiency was tested as acquisition of the language of the new country is theorized as a key indicator of integration and human capital, and at the same time, refugees’ language learning outcome may vary depending on their life experiences (Capps et al., 2015; Chiswick & Miller, 2001; Fennelly & Palasz, 2003).

Previous work-related experience was measured in two questions. Employment before coming to the U.S. was coded as a binary variable (Employed = 1, Unemployed = 0). Another variable considered was job training after coming to the U.S., which serves an important post-migration factor. The response to the survey question “Within the past 12 months, has this person attended any job training program?” was used as a measure of people’s interest in and efforts to obtain a job. The variable was a binary variable (Yes = 1, No = 0).

Multiple welfare benefits were calculated as variables, including cash assistance and non-cash assistance. Survey respondents are designated “Receives cash assistance” if they report one or more persons in their household receiving TANF, RCA, SSI, or GA in the twelve months before survey administration. The survey responses were coded as a binary variable (Received cash benefits = 1, Did not receive cash benefits = 0). Non-cash assistance comprised food and housing. The non-cash assistance variable was coded between 0 and 2 (Did not receive non-cash benefits = 0, Either receiving food stamps or residing in public housing = 1, Both = 2) in the twelve months before survey administration. In addition to the welfare benefits, whether refugees received medical support was considered. This variable captured respondents’ receipt of Refugee Medical Assistance (RMA, hereinafter) or Medicaid. RMA provides short-term medical coverage to refugees who are ineligible for Medicaid. RMA provides a medical screening upon arrival in the U.S. and benefits generally similar to Medicaid (ORR, 2022b). The response was coded as a binary variable (Yes = 1, No = 0).

Analysis

The descriptive statistics of variables are summarized in Table 2. Roughly 78% of the refugees in the sample had worked since their arrival in the U.S., including 62% who were working at the time of the survey and 16% who responded not currently working but had previously worked in the U.S. The sample comprised all working ages between 18 and 64, averaging 35.90 years. On average, refugees stayed in the U.S. for almost four years. Refugees had approximately 9 years and 7 months of education with an English proficiency level that was between “Not at all” and “Not well” before their arrival to the U.S. After coming to the in the U.S., 20% of refugees pursued education (including 7.8% high school diploma, 1.7% associate’s degree, 3.4% Bachelor’s degree, and 4.8% a Master’s or Doctorate, professional school degree (e.g., MD, LLB, and DDS), or certificate/licensure) with their English proficiency improved to the level between “Not well” and “Well.” About half of the refugees in the sample had an experience of working before coming to the U.S. After coming to the U.S., 14% of the sample participated in job training. In terms of welfare benefits, 20% of the sample received at least one type of cash assistance, 48% at least one type of non-cash assistance, 14% both types of non-cash assistance, and 44% medical support in the twelve months before the survey administration.

Given that some of the independent variables measured the same phenomenon at different time points (e.g., education and English proficiency before and after coming to the U.S.), the correlations and the variance inflation factor (VIF, hereinafter) were examined to detect multicollinearity. The results (Mean VIF = 1.38) confirmed that there is no severe correlation between a given explanatory variable and any other explanatory variables in the model. A VIF values less than 5 indicate a low correlation and are generally not problematic.

A multivariate logistic regression was employed to examine the effects of independent variables, including age, gender, country of birth, household composition, time in the U.S., educational attainment before and after migration, pre-migration work experience, post-migration job training, English proficiency before and after migration, and welfare assistance, on individuals’ employment status after resettling in the U.S. using Stata Software version 18.

Results

The result of regression analysis is shown in Table 3 (χ2 = 470.78, df = 25, p <0.01). In terms of demographic characteristics, both age and gender showed statistically significant associations. Those who were younger (OR = 0.99, 95% CI [0.97, 1.00]) and male refugees (OR = 2.73, 95% CI [2.19, 3.42]) were more likely to work. Each additional increase of one year in age was associated with a 1% decrease in the odds of working. The odds of working were 2.73 times higher for males than for females. Household composition was not found to be a statistically significant factor, although the negative co-efficient suggests that individuals in single-person households were more likely to have work experience in the U.S. than those in multiple-person households. The correlation between the two variables showed a small inverse relationship with statistically significance (r = −0.11, p < 0.01). Similarly, the duration since resettlement was not statistically significant, despite the positive co-efficient indicating that longer stays in the U.S. may provide more opportunities for employment. However, these two variables showed a very small correlation without statistical significance (r = 0.02, p = 0.38).

Refugees’ country of birth exhibited significant differences. Compared to the reference group (Iraq), individuals from neighboring countries in the Middle East (Afghanistan, Iran, and Syria) all showed lower odds of working (OR = 0.88, 95% CI [0.45, 1.70]; OR = 0.87, 95% CI [0.48, 1.58]; and OR = 0.72, 95% CI [0.48, 1.07], respectively) but with statistically insignificance (p = 0.70, p = 0.66, and p = 0.11, respectively). However, compared to those from Iraq, individuals from all the other regions (Asia, Africa, South America, and Other) displayed higher odds of work experience with statistical significance. For example, the odds of people from Bhutan, El Salvador, and Somalia working in the U.S. were more than twice as high as those from Iraq (OR = 2.46, 95% CI [1.53, 3.95]; OR = 2.21, 95% CI [1.30, 3.77]; and OR = 2.60, 95% CI [1.23, 5.48], respectively). Similarly, the odds of people from Burma, Congo, Ukraine, and other countries working were close to double those of the reference group with statistical significance (OR = 1.84, 95% CI [1.17, 2.90]; OR = 1.74, 95% CI [1.13, 2.67]; OR = 1.58, 95% CI [1.00, 2.50]; and OR = 1.52, 95% CI [1.02, 2.27] respectively). Those from Nepal followed a similar pattern albeit without statistical significance (OR = 1.91, 95% CI [0.97, 3.74]). Notably, individuals from Cuba exhibited the largest disparity, with odds of working 4.75 times higher than those from Iraq (OR = 4.75, 95% CI [2.13, 10.56]).

Education exhibited a different relationship with the odds of working before and after resettlement. Educational attainment before arriving in the U.S. positively predicted the odds of working (OR = 1.03, 95% CI [1.00, 1.06]), whereas after arriving in the U.S., it was negatively associated (OR = 0.53, 95% CI [0.39, 0.71]). Specifically, each additional year of pre-migration education was associated with a 3% increase in the odds of working. However, for each stage of advancement in educational degrees after arriving in the U.S., the odds of working decreased by nearly 40%.

English proficiency also showed a different relationship pre- and post-migration. Before arriving in the U.S., English proficiency was not a significant factor for predicting employment (OR = 0.97, 95% CI [0.81, 1.17]). However, the ability to speak better English was associated with a 26% increase in the odds of working after coming to the U.S. (OR = 1.26, 95% CI [1.05, 1.51]).

Work-related predictors were both significant both pre- and post-migration. Individuals who had worked before coming to the U.S. had approximately twice the odds of working compared to those who did not work (OR = 2.09, 95% CI [1.64, 2.65]). Moreover, those who participated in post-migration job training were 2.76 times more likely to have a job than those who did not (OR = 2.76, 95% CI [1.93, 3.96]).

Welfare predictors yielded mixed results. While cash assistance was not a significant predictor (OR = 0.85, 95% CI [0.66, 1.10], p = 0.22), both cash- and noncash-based benefits showed negative associations. Specifically, those who were receiving non-cash-based welfare assistance (e.g., food and housing) (OR = 0.68, 95% CI [0.58, 0.80]) and medical support (OR = 0.58, 95% CI [0.47, 0.72]) were less likely to work after resettlement, with each associated with a 32%, and 42% decrease in the odds of working, respectively.

Discussion

The results of this study confirm that certain pre-migration characteristics bear impact on refugees’ access to jobs. Specifically, sociodemographic characteristics such as age, gender, and educational attainment and previous working experience before arriving in the U.S. had significant associations with the likelihood of working after arriving in the U.S. These results echo the findings from previous research that highlighted gender differences in job pursuit and the advantages of possessing human capital from one’s home country and its transferability to the new country environment (Bellinger, 2013; Salikutluk & Menke, 2021; Vromans et al., 2018).

In addition, this study expands the discussion from pre-migration to post-migration factors, especially concerning the skills that may contribute to obtaining a job. For example, job training was a strong factor for the likelihood of working after resettlement, controlling previous work experience and educational level before migration. Furthermore, English proficiency after coming to the U.S. was a strong predictor associated with job outcomes, whereas English proficiency prior to arrival in the U.S. showed no significant association. These results suggest that while refugees with higher socioeconomic status may have advantages in securing jobs, the growth of refugees’ human capital also depends on how they adapt to the new environment. When job training is available locally, those resources can make a difference in refugees’ employment outcomes after migration. Comparatively, English proficiency is a complex variable that is not as easily interpretable as an outcome of locally available programs alone. Research has shown that many socioeconomic factors can influence one’s language skills, such as age at migration, level of literacy, ethnic background, educational level, or gender. Yet, English proficiency is considered one of the key assets for a successful transition to life in the U.S., and thus, relevant resources are offered by resettlement agencies and many refugee-serving organizations (Capps et al., 2015; ORR, 2023). Therefore, assuming that job- and language-related training can play a crucial role in enhancing people’s skills, these results can be interpreted as indicating that availability of these programs and refugees’ participation in them can help equip them with the skills conductive to obtaining jobs after resettlement.

The mixed results on welfare variables can be interpreted in various ways. When welfare is conceptualized as a resource for refugees to obtain a job, this result aligns with previous research highlighting that welfare assistances alone may be insufficient to support refugees’ employment and their lasting integration (Easton-Calabria & Omata, 2018; Frazier & van Riemsdijk, 2020; Lopalo, 2019; Shin, 2022). From that perspective, it may signal that the current welfare does not directly contribute to refugees’ employment outcomes given that cash assistance only runs for a short term and focuses on immediate settlement and survival. Even though non-cash assistance (e.g., food, housing, and healthcare) may provide support to refugees over a longer period, its primary purpose is to fulfill their basic needs. In this regard, it makes sense that welfare does not seem to directly impact employment outcomes. On the other hand, welfare can be seen as a deterrent to employment. For example, if an individual is in poor health (e.g., chronic illness) and qualifies for long-term assistance, the negative association between welfare and work is understandable to some extent. In this context, while welfare aids in refugee resettlement, it may not necessarily facilitate job acquirement. Therefore, welfare variables imply ambivalence and warrant careful interpretation.

Although the ASR dataset provided a wide array of variables, the interpretation of some of their impact is challenging due to a lack of contextual information. Particularly, the meaning of the dependent variable, working at a job, can be multifaceted and yet not fully known. Refugees’ working status may reflect their willingness to establish self-sufficiency, but the meaning of self-sufficiency and how individuals try to reach such a state is not clear. Refugees can take a job—any job—for survival rather than for their career. In fact, several studies support that refugees settle for the first and often low-wage job that does not reflect their educational background or labor market experience before coming to the U.S. (Chen & Hulsbrink, 2019; Kreisberg et al., 2022; Shin, 2022). Without contextualized information on people’s motivation to work, types of work, or satisfaction from work, our understanding of having a job remains limited.

Our interpretation of employment-related factors is also limited due to the use of cross-sectional data. Given that there was a strong association between refugees’ previous working experience in their home countries and their current working status in the U.S., it is possible that there is a common contributing factor, such as a sense of responsibility or skills to navigate the job market, that might have affected the employment outcomes at both times. However, such information is not available in the dataset. In addition, the cross-sectional nature of this study does not capture the effect of time. The only time-related variable used in this study was year of arrival, which was not found to be a statistically significant factor for employment outcome. The findings of this study suggest that refugees experience diverse realities that cannot be fully captured solely by considering time. On one hand, early arrival may suggest more time for adjustment that could have benefited the employment outcome. On the other hand, it is also possible that not all refugees are motivated to continue working if they experience “negative” assimilation, where their earnings decline over time in the destination country despite having skills that are highly transferable internationally (Chiswick & Miller, 2011). This highlights the complexity of refugee integration and the need for a nuanced understanding of the factors influencing their employment outcomes.

Another key information that is not addressed in this study is regarding the variances among localities due to the lack of information on where people are located. It is understandable that such information is hidden to protect the privacy of the survey participants. However, considering that the characteristics of social support are varied at the state and local levels, the impact of refugee resettlement and welfare programs can differ and yet are not captured. Having more details on the location of residence (e.g., urban and rural), the quality of services (e.g., training, housing) and resettlement practices (e.g., case management, RCA amount, and expectation to work) could have enriched the interpretation of the results. It is also noteworthy that the survey was collected during the time in which the number of refugees and resettlement programs significantly plummeted due to the change in the political climate (Mathema & Carratala, 2020). Although ASR provides a nationally representative sample, there still is a gap in understanding how each locality was affected by and responded to a drastic decrease in support for refugees.

Future research can continue to examine the group differences among various ethnic groups. The findings of this study revealed significant group differences, particularly indicating a lower likelihood of working among individuals from the Middle East compared to those from other regions. Previous research has discussed how refugees from certain origins may experience greater barriers to work in the U.S. based on their racial perception and religious affiliation (Colic-Peisker & Tilbury, 2006). For example, Somali Muslim refugees encountered a new dimension of race and racism upon arrival in the U.S. first due to the country’s systemic discrimination toward African Americans and more recently heightened hostility toward Muslims (Magan, 2020). While the classical assimilation theory argued that immigrants would eventually assimilate to their new societies (Nguyễn, 2021), critiques argue that the concept of assimilation connotes the “civilization” of non-white people, where white populations are more likely to assimilate while others are often subject to racialization (Ramírez, 2020). Although we were not able to delve into a discussion of race and culture extensively, as individuals may self-identify with multiple races within one country of origin, it is essential to recognize that race and culture can play a key role in the job market and educational systems in the U.S. (Hirsh, 2014; Morris & Thanasombat, 2011), which deserve closer examination in future research endeavors.

Regarding post-migration resources, more factors can be further examined, not only in terms of participation in job training but also in terms of the factors that may affect people’s participation, such as availability of job training, social support, neighborhood context, or technology skills in case that the training is offered online (Baranik et al., 2018; Kristiansen et al., 2022). For practice, resettlement agencies can consider ways to implement the post-arrival services in a way that will have a smooth transition into the local communities with a long-term perspective. Other organizations such as nonprofits, philanthropy, and faith-based communities can also design tailored support that will help people to develop tangible skills for job acquirement, such as providing apprenticeship opportunities and preparation for job interviews or working in a multicultural environment. Revisiting the concept of refugee integration, it is crucial to recognize that the responsibility of integration should be shared with the receiving society and its members, rather than solely shouldered by newcomers (Bottero, 2023), as integration is a process, not a status of the individual.

Moreover, this research prompts future research to incorporate the in-depth meaning of having a job and being self-sufficient into the analysis of refugee employment outcomes. The self-sufficiency of refugees in the U.S. is currently framed as equal to getting a job. However, the economic approach does not incorporate a myriad of non-economic factors that influence refugees’ self-sufficiency in social, institutional, and individual realms (Shalan, 2019). For example, can we refer to someone who settled for a low-paid job to receive welfare as self-sufficient? In addition, it is critical to remember that those who transition from welfare to work often continue to experience poverty-related struggles such as food insecurity and health problems (Breitkreuz & Williamson, 2012; Lightman et al., 2008). The current study also suggests that pursuit of education in the U.S., which can enhance refugees’ capability to be self-sufficient in the long run, may impede the immediate pursuit of jobs. In this regard, the meaning of economic self-sufficiency needs to be articulated and further distinguished from the other dimensions of sufficiency and associated concepts such as self-reliance and equal opportunities (Benson & Panaggio, 2019; Easton-Calabria & Omata, 2018).

Currently, the conceptual discussion on refugees’ self-sufficiency exists somewhat disjointedly from the research that analyzes the factors associated with refugee employment. Some studies examined both aspects (Bloch, 2007; Frazier & van Riemsdijk, 2020; Potocky-Tripodi, 2001), but mostly by using localized data (e.g., Baranik et al., 2018; Lumley-Sapanski, 2021). Ideally, a large dataset with a detailed questionnaire will help to make more generalizable conclusions about the meaning of having a job and the differences across age groups, ethnic backgrounds, or groups with various English proficiencies. To enable such research, researchers, and policymakers will need to discuss ways to collect and release information in a collaborative and ethically safe manner. Such information gathering and sharing can also benefit the resettlement processes at a local level. Specifically, in-depth information on refugees’ skills, capacities, desires, and potential contacts can help resettlement agencies place refugees in a location that offers a better chance of successfully integrating (Swing, 2017).

Further studies are needed to continue to distinguish the kind of welfare assistance that would make a difference in refugees’ employment outcomes, both in the short and long term. Specifically, the impact of having the pressure to acquire jobs shortly after arrival will need to be investigated because focusing on the short-term job outcome is found to have either a negative or zero correlation with the employment and earnings of the general population over the long term (Heckman et al., 2002). It is also possible that only a selected group of refugees take advantage of short-term resources (i.e., so-called a creaming of service use can occur), which then can lead to long-term unemployment for those who cannot easily find jobs (Shutes, 2011). Therefore, it is critical to reflect on where the welfare resources are focused: when the resources are mainly focused on helping people get any jobs quickly, it would miss the opportunity to help people to identify their interests, develop their skills, and find the jobs that would match their interests and skills. In that regard, the resources to make a more long-lasting job outcome can be more emphasized for future welfare programs.

The new emphasis on long-term outcomes is also convincing considering that many refugees are not in a situation in which they can pursue jobs immediately after arriving. For example, refugees in our study sample did not seek jobs because they had other burdens such as childcare responsibilities, poor health, or schoolwork, not because they doubted the availability of jobs. These aspects of reality encourage the refugee-service agencies to develop resources that will help individuals to either first invest in other competing priorities in life before seeking jobs or to obtain jobs that they can manage along with other life events. Meeting the critical needs of people’s everyday lives will be an important factor in reaching a more holistic meaning of self-sufficiency in future practice.

Data Availability

This research used publicly available data.

References

Ager, A., & Strang, A. (2008). Understanding integration: A conceptual framework. Journal of Refugee Studies, 21(2), 166–191. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fen016

Baranik, L. E. (2021). Employment and attitudes toward women among Syrian refugees. Personnel Review, 50(4), 1233–1252. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-10-2018-0435

Baranik, L. E., Hurst, C. S., & Eby, L. T. (2018). The stigma of being a refugee: A mixed-method study of refugees’ experiences of vocational stress. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 105, 116–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.09.006

Battisti, M., Giesing, Y., & Laurentsyeva, N. (2019). Can job search assistance improve the labour market integration of refugees? Evidence from a field experiment. Labour Economics, 61, 101745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2019.07.001

Benson, O. G. (2016). Refugee resettlement policy in an era of neoliberalization: A policy discourse analysis of the Refugee Act of 1980. Social Service Review, 90(3), 515–549. https://doi.org/10.1086/688613

Bellinger, G. A. (2013). Negotiation of gender responsibilities in resettled refugee populations through relationship enhancement training. Transcultural psychiatry, 50(3), 455–471.

Benson, O. G., & Panaggio, A. T. (2019). “Work is worship” in refugee policy: Diminution, deindividualization, and valuation in policy implementation. Social Service Review, 93(1), 26–54. https://doi.org/10.1086/702182

Bloch, A. (2007). Refugees in the UK Labour Market: The conflict between economic Integration and Policy-Led Labour Market Restriction. Journal of Social Policy, 37(1), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S004727940700147X

Boss, H. C., Lee, C. S., Bourdage, J. S., & Hamilton, L. K. (2022). Developing and testing a framework for understanding refugees’ job search processes. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 41(4), 568–591. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-01-2021-0031

Bottero, M. (2023). Integration (of immigrants) in the European courts’ jurisprudence: Supporting a pluralist and rights-based paradigm? Journal of International Migration and Integration, 24, 1719–1750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-023-01027-7

Breitkreuz, R. S., & Williamson, D. L. (2012). The self-sufficiency trap: A critical examination of welfare-to-work. Social Service Review, 86(4), 660–689. https://doi.org/10.1086/668815

Bridekirk, J., & Hynie, M. (2021). The impact of education and employment quality on self-rated mental health among Syrian refugees in Canada. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 23(2), 290–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-01108-0

Capps, R., Newland, K., Fratzke, S., Groves, S., Auclair, G., Fix, M., & McHugh, M. (2015). Integrating refugees in the United States: The successes and challenges of resettlement in a global context. Statistical Journal of the IAOS, 31(3), 341–367. https://doi.org/10.3233/SJI-150918

Chen, X., & Hulsbrink, E. B. (2019). Barriers to achieving “economic self-sufficiency”: The structural vulnerability experienced by refugee families in Denver, Colorado. Human Organization, 78(3), 218–229. https://doi.org/10.17730/0018-7259.78.3.218

Chiswick, B. R., & Miller, P. W. (2001). A model of destination-language acquisition: Application to male immigrants in Canada. Demography, 38, 391–409. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2001.0025

Chiswick, B. R., & Miller, W. (2011). The “negative” assimilation of immigrants: A special case. ILR Review, 64(3), 502–525.

Colic-Peisker, V., & Tilbury, F. (2006). Employment niches for recent refugees: Segmented labour market in twenty-first century Australia. Journal of Refugee Studies, 19(2), 203–229.

Darrow, J. H. (2018). Administrative indentureship and administrative inclusion: Structured limits and potential opportunities for refugee client inclusion in resettlement policy implementation. Social Service Review, 92(1), 36–68. https://doi.org/10.1086/697039

Disney, L., & McPherson, J. (2020). Understanding refugee mental health and employment issues: Implications for social work practice. Journal of Social Work in the Global Community, 5, 19–30. https://doi.org/10.5590/JSWGC.2020.5.1.02

Due, C., Callaghan, P., Reilly, A., Flavel, J., & Ziersch, A. (2021). Employment for women with refugee and asylum seeker backgrounds in Australia: An overview of workforce participation and available support programmes. International Migration, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12848

Easton-Calabria, E., & Omata, N. (2018). Panacea for the refugee crisis? Rethinking the promotion of ‘self-reliance’ for refugees. Third World Quarterly, 39(8), 1458–1474. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2018.1458301

Favell, A. (2022). The integration nation: Immigration and colonial power in liberal democracies. Polity Press.

Fennelly, K., & Palasz, N. (2003). English language proficiency of immigrants and refugees in the Twin Cities metropolitan area. International Migration, 41(5), 93–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0020-7985.2003.00262.x

Fix, M., Hooper, K., & Zong, J. (2017). How are refugees faring? Integration at US and State levels. Migration Policy Institute https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/TCM-Asylum-USRefugeeIntegration-FINAL.pdf

Frazier, E., & van Riemsdijk, M. (2020). When ‘self-sufficiency’ is not sufficient: Refugee integration discourses of US resettlement actors and the offer of refuge. Journal of Refugee Studies, 34(3), 3113–3130. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa119

Freudenberg, J., & Halberstadt, J. (2018). How to integrate refugees into the workforce – Different opportunities for (social) entrepreneurship. Problemy Zarzadzania, 16(73), 40–60. https://doi.org/10.7172/1644-9584.73.3

Gibson, I. (2023). Refugees and asylees: 2022. Office of Homeland Security Statistics https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/2024-02/2023_0818_plcy_refugees_and_asylees_fy2022_v2.pdf

Heckman, J. J., Heinrich, C., & Smith, J. (2002). The Performance of Performance Standards. Journal of Human Resources, 37(4), 778–811. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069617

Hirsh, C. E. (2014). Beyond treatment and impact: A context-oriented approach to employment discrimination. American Behavioral Scientist, 58(2), 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213503328

Jackson, S., & Bauder, H. (2014). Neither temporary, nor permanent: the precarious employment experiences of refugee claimants in Canada. Journal of Refugee Studies, 27(3), 360–381. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fetO48

Kallick, D. D., & Mathema, S. (2016). Refugee integration in the United States. Center for American Progress and Fiscal Policy Institute. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/refugee-integration-in-the-united-states/

Khawaja, N. G., & Hebbani, A. (2018). Does employment status vary by demographics? An exploratory study of former refugees resettled in Australia. Australian Social Work, 71(1), 71–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2017.1376103

Klarenbeek, L. M. (2021). Reconceptualising ‘integration as a two-way process’. Migration Studies, 9, 902–921. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnz033

Kreisberg, A. N., De Graauw, E., & Gleeson, S. (2022). Explaining refugee employment declines: Structural shortcomings in federal resettlement support. Social Problems, Spab080. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spab080

Kristiansen, M. H., Maas, I., Boschman, S., & Vrooman, C. (2022). Refugees’ transition from welfare to work: A quasi-experimental approach of the impact of the neighbourhood Context. European Sociological Review, 38(2), 234–251. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcab044

Lightman, E., Herd, D., & Mitchell, A. (2008). Precarious lives: Work, health and hunger among current and former welfare recipients in Toronto. Journal of Policy Practice, 7(4), 242–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/15588740802258508

LoPalo. (2019). The effects of cash assistance on refugee outcomes. Journal of Public Economics, 170, 27–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2018.11.004

Lumley-Sapanski, L. (2021). The survival job trap: Explaining refugee employment outcomes in Chicago and the contributing factors. Journal of Refugee Studies, 34(2), 2093–2123. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fez092

Magan, I. M. (2020). On being black, Muslim, and a refugee: Stories of Somalis in Chicago. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 18(2), 172–188.

Mathema, S., & Carratala, S. (2020). Rebuilding the U.S. refugee program for the 21st century. Center for American Progress https://www.americanprogress.org/article/rebuilding-u-s-refugee-program-21st-century/

Morris, M. W., & Thanasombat, S. (2011). Race, culture and the pursuit of employment: A research series on hiring practices at temporary employment agencies. In R. D. Coates (Ed.), Covert racism: Theories, institutions, and experiences (Vol. 32, 1st ed., pp. 175–188). https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004203655.i-461.66

Nguyễn, L. T. (2021). “Loving couples and families:” Assimilation as honorary whiteness and the making of the Vietnamese refugee family. Social Sciences, 10(6), 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10060209

Office of Refugee Resettlement. (2022a). Annual survey of refugees. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/programs/refugees/annual-survey-refugees

Office of Refugee Resettlement (2022b). Cash & medical assistance. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/programs/refugees/cma

Office of Refugee Resettlement (2023). Resettlement services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/orr/programs/refugees

Ortlieb, R., & Knappert, L. (2023). Labor market integration of refugees: An institutional country-comparative perspective. Journal of International Management, 29(2), 101016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2023.101016

Potocky, M., & Naseh, M. (2019). Asylum seekers, refugees, and immigrants in the United States. In Encyclopedia of Social Work https://oxfordre.com/socialwork/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.001.0001/acrefore-9780199975839-e-193

Potocky-Tripodi, M. (2001). Micro and macro determinants of refugee economic status. Journal of Social Service Research, 27(4), 33–60. https://doi.org/10.1300/J079v27n04_02

Race, K. E. H., & Masini, B. E. (1996). Factors associated with early employment among refugees from the former Soviet Union. Journal of Employment Counseling, 33(2), 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1920.1996.tb00439.x

Ramírez, C. (2020). Assimilation: An alternative history. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520971967

Refugee Act of 1980. PL 96-212. 96th United States Congress, March 17, 1980.

Renner, W., & Senft, B. (2013). Predictors of unemployment in refugees. Social Behavior and Personality, 41(2), 263–270. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2013.41.2.263

Rytter, M. (2019). Writing against integration: Danish imaginaries of culture, race and belonging. Ethnos, 84(4), 678–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2018.1458745

Salikutluk, Z., & Menke, K. (2021). Gendered integration? How recently arrived male and female refugees fare on the German labour market. Journal of Family Research, 33(2), 284–321. https://doi.org/10.20377/jfr-474

Schinkel, W. (2018). Against ‘immigrant integration’: For an end to neocolonial knowledge production. Comparative Migration Studies, 6(1), 31–31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-018-0095-1

Shaffer, R., Pinson, L. E., Chu, J. A., & Simmons, B. A. (2020). Local elected officials’ receptivity to refugee resettlement in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(50), 31722–31728.

Shalan, M. (2019). In pursuit of self-reliance – perspectives of refugees in Jordan. International Journal of Architectural Research, 13(3), 612–626. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARCH-04-2019-0085

Shin, S. (2022). To work or not? Wages or subsidies?: Copula-based evidence of subsidized refugees’ negative selection into employment. Empirical Economics, 63, 2209–2252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-022-02202-y

Shutes, I. (2011). Welfare-to-work and the responsiveness of employment providers to the needs of refugees. Journal of Social Policy, 40(3), 557–574. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279410000711

Singer, A., & Wilson, J. H. (2006). From ‘there’ to ‘here’: Refugee resettlement in Metropolitan America. Metropolitan Policy Program, Brookings Institution.

Stempel, C., & Alemi, Q. (2021). Challenges to the economic integration of Afghan refugees in the U.S. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(21), 4872–4892. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1724420

Swing, W. L. (2017). Practical considerations for effective resettlement. Forced Migration Review, 54, 4–5.

Tran, V. C., & Lara-García, F. (2020). A new beginning: Early refugee integration in the United States. Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 6(3), 117–149. https://doi.org/10.7758/RSF.2020.6.3.06

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2023a). Figures at a glance. https://www.unhcr.org/us/about-unhcr/who-we-are/figures-glance

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2023b). Refugee Livelihoods and Economic Inclusion - 2019-2023 Global Strategy Concept Note. https://www.unhcr.org/media/refugee-livelihoods-and-economic-inclusion-2019-2023-global-strategy-concept-note

United States Department of State (2023). U.S. refugee admissions program. https://www.state.gov/refugee-admissions/

United States Government Accountability Office (2012). Refugee resettlement: Greater consultation with community stakeholders could strengthen program. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-12-729

Vromans, L., Schweitzer, R. D., Farrell, L., Correa-Velez, I., Brough, M., Murray, K., & Lenette, C. (2018). ‘Her cry is my cry’: Resettlement experiences of refugee women at risk recently resettled in Australia. Public Health, 158, 149–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.03.010

Ward, N., & Batalova, J. (2023). Refugees and asylees in the United States. Migration Policy Institute https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/SPT-Refugees2023-PRINT-final.pdf

Wimpelmann, T. (2017). The pitfalls of protection: Gender, violence, and power in Afghanistan ((1st ed.). ed.). University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/luminos.32

Yako, R. M., & Biswas, B. (2014). “We came to this country for the future of our children. We have no future”: Acculturative stress among Iraqi refugees in the United States. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 38, 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.08.003

Zubaroglu-Ioannides, P., & Yalim, A. C. (2022). US resettlement policies and their impact on refugee wellbeing: Perspectives of service providers in New York City. Journal of Social Service Research, 48(4), 577–592. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2022.2097979

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conceptualization. Literature review and design of Fig. 1 were conducted by Jeesoo Jung. Study design and analysis were performed by Wonhyung Lee. Manuscript writing was led by Wonhyung Lee.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, W., Jung, J. The Impact of Post-migration Support for Refugees’ Job Acquirement in the U.S.. Int. Migration & Integration 25, 1645–1665 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-024-01143-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-024-01143-y