Abstract

Despite increasing interest in topics related to refugees, economic literature has remained mostly silent on how refugees make labor supply decisions in their initial resettlement period, during which their host government provides various care and financial assistance. This paper fills that void by applying the copula-based selection model, which is free from the restrictive joint normality assumption, to a unique, high-dimensional data set of refugees who resettled in the US. Its selection parameter estimates suggest that subsidized refugees negatively select themselves into employment in terms of unobserved wage potential, which, according to the theoretical model, should be attributed primarily to the fact that (i) their reservation wages are rigid due to host-provided, non-labor income and (ii) host country employers discount refugees’ unobserved human capital components substantially. As a result, employed refugees’ wages, all observable factors held constant, are lower than the counterfactual wages of non-employed refugees, which contradicts what is usual in conventional labor markets. This devaluation-based skill paradox is more pronounced in regions unfriendly to refugees, and the negative pattern temporarily reversed immediately after the 9/11 attacks, which represented a huge adverse shock to non-natives in the US labor market, suggesting that subsidized refugees’ labor supply decisions are influenced greatly by their expectations regarding future labor market outcomes. Possible explanations are discussed based on a simple theoretical model in the context of the US refugee resettlement system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent years, the number of people displaced forcibly has increased rapidly, creating an era of diaspora (Shin 2021). According to the United Nations refugee agency, as of 2020, 82.4 million people have been dislocated involuntarily worldwide, and 26.4 million are officially registered as refugees by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) or the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA). Moreover, the United Nations recently warned that up to half a million Afghans could flee their country by the end of 2021. Concerning the hosting of refugees, fiery discussions are not over and will likely continue in the near future. Some researchers, such as Tumen (2016) and Akar and Erdoğdu (2019), underscore the myriad of social and economic issues expected to occur with their exodus. In contrast, others, such as Bodewig (2015) and d’Artis Kancs and Lecca (2018), accentuate several positive aspects, the main point of which lies in the expectation that the influx of refugees will invigorate host countries with an active, younger working population (Bodewig 2015; Desilver 2015).Footnote 1 The achievability of that expectation, however, hinges on whether nations in charge of helping such refugees become economically self-sufficient as soon as possible. A refugee creates a fiscal surplus in a host country if and only if the net present value of his or her tax payments exceeds that of the costs that he or she imposes. Thus, refugees generate a surplus only when they are integrated into local labor markets (Borjas et al. 2019).

Despite economists’ increasing interest in topics related to refugees, little attention has been paid to the question of how refugees, while initially placed under host-provided care, select themselves into work—especially in terms of important but unobservable human capital, which decides their potential wages combined with observable characteristics.Footnote 2 From an econometric perspective, this question concerns a previously unexplored relationship between what affects (i) refugees’ employment participation and (ii) their market wages. A systematic understanding of this relationship is lacking because most extant studies investigate either the former or latter separately, not links between them. This intertwinement concerns an important microeconomic concept—selection into employment—which is often made in a systematic, endogenous way.

In labor economics, the importance of allowing for non-random selection into employment has received much attention since Gronau (1974), Heckman (1976), Heckman (1979), and Barnow et al. (1981). Conventional wisdom concerning usual labor markets suggests that selection into work is made positively, as demonstrated empirically by many extant studies, such as Smith and Ward (1989), Blau and Kahn (2006), Olivetti and Petrongolo (2008), Arellano and Bonhomme (2017), and Dolado et al. (2020). This is intuitive because it becomes more expensive for those with high wage potential to remain out of work (Mulligan and Rubinstein 2008). However, one question is whether it holds for subsidized refugees, a question that economic research has not yet addressed.Footnote 3

Using the theoretical concept of selection into employment, this study addresses the question of how newly arrived refugees make labor supply decisions while being subsidized. In particular, it explores whether unobservable human capital factors that raise the wages that a refugee receives during employment increase (or decrease) the probability that he or she enters employment. For this purpose, the copula-based selection model from Smith (2003) is applied to a unique, high-dimensional data set of refugees who resettled in the US. The copula approach is econometrically beneficial primarily in the sense that joint normality is not required, and its estimates are thus considered less assumption-dependent than those from other common methods.

In the local labor markets of their resettlement regions, refugees are severely disadvantaged in comparison to host populations (Shin 2021). A lack of local language skills, cultural differences, career interruptions, undervalued work experience, and unappreciated educational attainments are a few examples of such obstacles. However, officially admitted ‘newcomer’ refugees receive cash assistance, housing, medical care, and administrative assistance from their host government. By virtue of these host-provided benefits, refugees do not have impending concerns about their livelihoods, in contrast to jobless members of the host population and economic migrants.Footnote 4 Such host-provided assistance and non-labor income are secured for a substantial period; for example, some benefits, such as Supplemental Security Income, Medicaid, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, are provided for at least five to seven years after entry (Bruno 2017). This institutional setup can solidify subsidized refugees’ lack of financial urgency and, accordingly, cause their labor supply behaviors to be unconventional. Therefore, this paper begins with the hypothesis that refugees’ selection into employment deviates from conventional selection patterns, which nearly always turn out positive. Rather, due to the unique institutional setup discussed above, the selection pattern can be negative, which means that refugees with higher (lower) wage potential, observable factors held constant, are less (more) likely to take employment. Negative selection into employment has often been considered problematic and viewed as an abnormal symptom that derives from misspecification (Ermisch and Wright 1994). However, in the case of subsidized refugees with no impending livelihood concerns, negative selection is not nonsensical, especially when host country employers discount their unobserved human capital substantially.

Findings on refugees’ unique selection pattern are expected to provide policymakers with meaningful implications, because their selection pattern is determined by a function of which and how many refugees are employed (Mulligan and Rubinstein 2008). If negative selection, as hypothesized above, is the case, it leads to the policy implication that employed refugees, on average, are those with lower wage potential and weaker productivity (Borjas et al. 2019). Equivalently, it means that refugees with higher wage potential and greater productivity are not employed, and as a result, the refugee workforce composition becomes less productive, and income tax revenues collected from employed refugees can be lower than those under a positive selection case. As discussed by Aksoy and Poutvaara (2021), to the extent that human capital is driving economic growth, this should be recognized as a definite loss to host societies. To offset this loss, those not in early employment should, from a long-term perspective, end up with better-quality jobs, which, however, is neither guaranteed nor substantiated.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the theoretical framework that underlies analysis. Data used during investigation are introduced in Sect. 3, including explanations of the institutional context. Section 4 discusses the econometric methods used to assess how subsidized refugees select themselves into employment. Estimation results are reported in Sect. 5, and Sect. 6 explains the robustness checks regarding further relaxing some assumptions and excluding alternative interpretations of results. Section 7 concludes the paper. For brevity, less important details appear in “Appendix” and Online supplement.

2 Theoretical framework

2.1 Microeconomic model

Following extant literature, such as Ermisch and Wright (1994) and Borjas et al. (2019), this section explains the current study’s theoretical framework. I start by defining two distinct (\(\log \)) hourly wage equations separately: (i) a reservation wage (or asking wage) equation and (ii) a market wage (or wage offer) equation. The market wage refers to how much employers are willing to pay for one hour of work, and the reservation wage represents how much a person requires to be ‘bribed’ into working that first hour (Borjas and Van Ours 2010).Footnote 5 Note that (i) the reservation wage is not observed directly and (ii) the market wage is observed if and only if a person is employed.

The reservation wage equation is expressed as:

where observable \(\mathbf {h}\) is a \(k\times 1\) vector of individual features and controls that affect the reservation wage of refugee i. \(\alpha _{\text {r}}\) is simply an intercept. The final term, \(v_{\text {r}_{i}}\), represents unobservable factors that are not fully explained by \(\mathbf {h}\) but nonetheless affect the reservation wage of i.Footnote 6 Similarly, the Mincer (1958, 1974) market wage equation can be written as:

where \(\mathbf {z}\) is a \(j\times 1\) vector of human capital attributes (e.g., schooling and labor market experience) and other controls observed in a data set. \(\alpha _{\text {m}}\) is a constant term. Like in (1), \(v_{\text {m}_{i}}\), in the form of market wage residuals, represents unobserved components that are not entirely explained by observable factors \(\mathbf {z}\) but affect the market wage of i.Footnote 7 The subscript i that indexes an individual refugee is hereafter omitted for notational simplicity.

A person’s wage determinants consist of observed (i.e., \(\mathbf {h}\) and \(\mathbf {z}\)) and unobserved (i.e., \(v_{\text {r}}\) and \(v_{\text {m}}\)) components, but an econometrician can observe only the former (Hwang et al. 1992). Since Juhn et al. (1993), the role of unobserved skills (and capabilities) in determining wage levels has been widely recognized.Footnote 8 Given the importance of unobserved human capital, hereafter denoted by s, this study decomposes \(v_{\text {r}}\) and \(v_{\text {m}}\) into:

and

respectively. In both (3) and (4), non-identical \(s\sim N(\mu _{s},\sigma _{\varepsilon _{s}}^{2})\) refers to unobserved human capital (i.e., unobserved productivity-related factors).Footnote 9 The concept of s is often intentionally left abstract, but it includes various unobserved components, such as capabilities, skills, intelligence, productivity, perseverance, reputation, personal traits, motivation, and taste for work and additional learning (Weiss 1995; Taber 2001; Dostie and Léger 2009).Footnote 10 Skill, used interchangeably with capability and human capital in this paper, is a broad, inclusive term, and a distinction between observable and unobservable skills is necessary in the current context. Clearly, the distinction is data and specification dependent. As Borjas et al. (2019) articulate, observable skills refer to the (conditioned) variables that explain wage levels and that are included in data (e.g., English proficiency). Unobservable skills are the wage components that are left unexplained by data. The former, as elements in \(\{h_{1},h_{2},...,h_{k}\}\) and \(\{z_{1},z_{2},...,z_{j}\}\), is observed by an econometrician, but the latter, denoted s, cannot be observed (Gould and Moav 2016). Individual refugees know the degree of their own s, and employers indirectly recognize s and reward it in a wage offer (Booth and Frank 1999; Praag and Cramer 2001). Thus, s appears in both (3) and (4), and \(\gamma _{q}>0\) for \(q\in \{\text {r},\text {m}\}\) gives the rate of return for s in each equation.

Another (skill-unrelated) component, \(\varepsilon _{q}\) for \(q\in \{\text {r},\text {m}\},\) represents all other unobserved factors that do not correlate with s.Footnote 11 By this definition

holds. Recall that the distinction between observable and unobservable components is determined by how an empirical framework, based on a data set, is specified. The more variables \(\mathbf {h}_{k\times 1}\) and \(\mathbf {z}_{j\times 1}\) encompass (i.e., higher k and j), the less \(\varepsilon _{q}\) for \(q\in \{\text {r},\text {m}\}\) explains variations in each dependent variable.Footnote 12 Suppose \(\mathbf {h}\) and \(\mathbf {z}\) are high dimensional, and thus

holds.Footnote 13 (5) and (6) are crucial to assuming that (i) the only channel that can connect  and

and  is s and (ii) thus the non-zero correlation of disturbances across two distinct wage equations (1) and (2) can materialize only through s.

is s and (ii) thus the non-zero correlation of disturbances across two distinct wage equations (1) and (2) can materialize only through s.

Regarding \(\text {Corr}(v_{\text {r}},v_{\text {m}})\), a stylized fact points to

meaning that unobserved components in market and non-market sectors correlate positively (Mulligan and Rubinstein 2008). This argument is substantiated by Heckman (1974), whose results suggest that \(\text {Corr}(v_{\text {r}},v_{\text {m}})\) is large and positive.

Based on the decomposition of (3), the reservation wage equation (1) can be rewritten:

with non-identical \(\varepsilon _{\text {r}}\sim N(0,\sigma _{\varepsilon _{\text {r}}}^{2})\). Similarly, the market wage equation (2), as a result of (4), can be rewritten:

with non-identical \(\varepsilon _{\text {m}}\sim N(0,\sigma _{\varepsilon _{\text {m}}}^{2})\). According to Heckman (1974), a decision to enter employment depends on a comparison of market wages (9) and reservation wages (8). Thus, an individual refugee decides to accept a job offer and go into employment when

holds, which leads to employment index function:

A refugee decides to work if and only if \(\mathbb {I}=\log (w^{\mathrm{m}}/w^{\mathrm{r}})>0\), and thus binary employment indicator \(D\in \{0,1\}\) can be defined as:

For analytical convenience, suppose in this section that  and

and  follow a bivariate normal distribution.Footnote 14 The variance of

follow a bivariate normal distribution.Footnote 14 The variance of  ,

which is the unobservable part of \(\mathbb {I}\), is then simply:

,

which is the unobservable part of \(\mathbb {I}\), is then simply:

Based on the probit link function, the probability that a refugee enters employment is:

where  is the union of

is the union of  and

and  . As is customary,

. As is customary,  is the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution.Footnote 15 In the second line of (14), a reduced-form employment equation appears. Recall that selection into employment on unobservables is measured by

is the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution.Footnote 15 In the second line of (14), a reduced-form employment equation appears. Recall that selection into employment on unobservables is measured by

the correlation between the error term of the market wage equation and that of the employment equation. For notational simplicity,  is hereafter expressed as

is hereafter expressed as  with

with  , the square root of (13). Thus, the correlation between \(v_{\text {m}}\) and \((v_{\text {m}}-v_{\text {r}})/\kappa \) can be expressed as:

, the square root of (13). Thus, the correlation between \(v_{\text {m}}\) and \((v_{\text {m}}-v_{\text {r}})/\kappa \) can be expressed as:

which reduces how a refugee, in terms of unobservables, self-selects into employment to a single selection parameter \(\rho _{v_{\text {m}},(v_{\text {m}}-v_{\text {r}})/\kappa }\). The detailed derivation of (16) is discussed in “Appendix A.1.” The sign of (16) is informative, indicating in which direction selection on unobservables is made. In the last row of (16), since C cannot be negative, the sign of

solely determines the sign of \(\rho _{v_{\text {m}},(v_{\text {m}}-v_{\text {r}})/\kappa }\).

In order to proceed, note that the total residual variance of market wage equation (9) can be decomposed as:

where the third row equality holds according to (5). Dividing both sides of (18) by \(\sigma _{v_{\text {m}}}^{2}\) leads to:

From (19), new notation

is introduced and hereafter used for notational simplicity. By the mathematical nature of \(\Theta \), \(0<\Theta <1\) holds, and \(\{\Theta ,1-\Theta \}\) can be seen as weighting parameters in (17). In (19), the first left-hand side term, \(\gamma _{\text {m}}^{2}\sigma _{\varepsilon _{s}}^{2}/\sigma _{v_{\text {m}}}^{2}\), represents the portion of \(\sigma _{v_{\text {m}}}^{2}\) attributable to the variance that derives from s, and the second term, \(\sigma _{{\varepsilon _{\text {m}}}}^{2}/\sigma _{v_{\text {m}}}^{2}\), is the portion of \(\sigma _{v_{\text {m}}}^{2}\) attributable to the variance that derives from \(\varepsilon _{\text {m}}\). Recall here that (i) s and \(\varepsilon _{\text {m}}\) are the two distinct components of unobservables that affect market wages in (9) and (ii) \(\Theta \) and \(1-\Theta \) are weighting parameters. Therefore, \(\Psi \) in (16) and (17) can be interpreted as the weighted average of A and B. A, which is a function of structural parameters related to s, is weighted by how much \(\gamma _{\text {m}}^{2}\sigma _{\varepsilon _{s}}^{2}\) contributes to \(\sigma _{v_{\text {m}}}^{2}\): similarly, B, which is a function of structural parameters related to \(\varepsilon _{\text {m}}\), is weighted by how much \(\sigma _{{{\varepsilon _{\text {m}}}}}^{2}\) contributes to \(\sigma _{v_{\text {m}}}^{2}\) (Borjas et al. 2019).

According to assumption (6),

holds. Thus, (16) can be simplified to:

and its sign, which is of interest in this study, is determined by the sign of \(\Theta (1-\frac{\gamma _{\text {r}}}{\gamma _{\text {m}}})+(1-\Theta )\). After rearrangement, if

holds, then positive selection (on s) into employment occurs. In (23), it can be seen that the core of the matter reduces to comparing market valuation of s (i.e., \(\gamma _{\text {m}}\)) and non-market valuation of s (i.e., \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\)). If \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\) and \(\gamma _{\text {m}}\) are approximately equal, (23) holds because of \(0<\Theta <1\), and a refugee positively self-selects into employment in terms of s. In contrast, selection is made negatively if

holds. For negative selection to occur, \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\) should be sufficiently larger than \(\gamma _{\text {m}}\), or \(\gamma _{\text {m}}\) should be sufficiently smaller than \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\), since (24) can be rearranged as:

Therefore, the composition of employed refugees, \(\{i\mid D_{i}=1\}\), changes in response to whether either (23) or (24) holds.

2.2 Selection into employment and market wages

If (24) or (25) holds, it indicates that the payoff for a refugee’s unobserved human capital s in the labor market is much lower than in his or her self-valuation. In that case, negative selection is understandable because refugees likely feel that host country employers undervalue their unobserved human capital. Hakak and Al Ariss (2013) and Dietz et al. (2015) demonstrate that non-native workers obtain sub-par outcomes in their host country labor markets because their capabilities and skills are devalued systematically.Footnote 16

Such negative selection in terms of s can affect the refugee workforce composition \(\{i\mid D_{i}=1\}\) and, accordingly, the distribution of observed market wages. In this section, \(\mathbf {z}=\mathbf {h}\) is assumed for simplicity, and suppose that observables take on particular values. The (untruncated) distribution of refugees’ potential market wages can be expressed as:

from (9). Under Heckman’s (1976; 1979) assumptions, the expectation of the market wage distribution of employed refugees \(\{i\mid D_{i}=1\}\) is:

where \(\phi (\cdot )/\Phi (\cdot )=\lambda (\cdot )\) refers to the inverse Mills ratio (Greene 2002). For further interpretations, recall that \(\lambda (\cdot )\ge 0\). All other notations are the same as above. If selection into employment is made negatively with \(\rho _{v_{\text {m}},(v_{\text {m}}-v_{\text {r}})/\kappa }<0\), the bracketed term in (27) is always negative due to the mathematical nature of \(\sigma _{v_{\text {m}}}\) and \(\lambda (\cdot )\), unless \(\lambda (\cdot )=0\). Therefore, negative selection makes

hold, in which the equality holds if and only if \(\lambda (\cdot )\) equals zero. Simply, (28) suggests that the mean of the market wage distribution of employed refugees (i.e., the mean of the truncated distribution) is less than that of a counterfactual, no-truncation case over the range in which \(\lambda (\cdot )>0\) holds—because refugees’ negative selection into employment ‘pushes down’ the conditional mean of the observed \(\log w^{\mathrm{m}}\) distribution of \(\{i\mid D_{i}=1\}\) in the direction of \(\rho _{v_{\text {m}},(v_{\text {m}}-v_{\text {r}})/\kappa }<0\). If selection into employment is made negatively, (27) also leads to:

in which the equality holds if and only if \(\lambda (\cdot )\) equals zero. In words, (29) means that the average market wage of employed refugees, observables \(\mathbf {z}\) held constant, is less than the average (counterfactual) market wage of non-employed refugees \(\{i\mid D_{i}=0\}\).

3 Data and institutional context

3.1 Data

A unique, high-dimensional refugee data set is used to apply the theoretical framework to real-world cases.Footnote 17 The repeated cross-sectional data used in this paper describe refugees who resettled in the US between 2001 and 2005, distributed across 16 resettlement cities by a refugee resettlement agency.Footnote 18 This exogenous distribution policy precluded individuals from systematic sorting.Footnote 19 Managed by the International Rescue Committee (IRC), the data represent a sample of 1,703 male adult refugees. Diverse variables were compiled prior to their arrival in the US territory by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) and the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM), and given later to the IRC. Refugees’ employment outcomes were recorded individually 90 days after each refugee’s arrival in his resettlement city.Footnote 20 Thus, such a quasi-administrative feature obviates the risk of systematic non-response or non-random exclusion. The data set is unique in three ways.

First, all individuals in the data set are refugees—neither economic migrants nor usual non-natives. According to the United States Immigration and Nationality Act Section 101, a refugee is a person unwilling or unable to remain in the country of their nationality due to serious persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution. For details, see Online supplement B.1. According to a definition from the European Commission, an economic migrant, on the other hand, is someone who leaves his or her country of origin purely for economic reasons that are not in any way related to the refugee definition mentioned above.Footnote 21 They migrate to live in another country with better working or living conditions.Footnote 22 This distinction is important in that economic migrants, as Borjas (1987) initially argued, generally select themselves from the populations of their home countries, unlike refugees who are displaced forcibly. Therefore, refugees are likely to be much more heterogeneous in comparison to economic migrants in terms of individual characteristics.Footnote 23

Second, sample respondents did not have family members who had already settled in the US and who could thus assist in their resettlement (Shin 2021, 2022).Footnote 24 In other words, they had no consanguinity ties in the US by the time they arrived. This facet makes the effect of individual-level features, including the pattern of selection into employment, much clearer because they had no family members to rely on during their initial settlement. Discussed in many studies, including Waldinger (1997), Potocky-Tripodi (2004), Lamba (2008), Allen (2009), and Jamil et al. (2016), informal assistance from relatives affects refugees’ labor market outcomes and economic adaptation through a channel of social capital. Thus, unless relevant information is recorded accurately, having family members established in the host country, before a refugee’s arrival, and the effects of social capital that derive from their assistance can contaminate estimates.Footnote 25 The data set is free from this issue (Shin 2021, 2022).

Third, in terms of dimensions of covariates, various individual characteristics were observed and recorded, allowing a range of controls, such as age, household size, ethnicity, religion, initial English-language proficiency, work experience, and education received before coming to the US. This high-dimensional feature is advantageous to assessing selection on unobservables because selection patterns are measured by the correlation of disturbances across employment and market wage equations. Errors are necessarily tied up with how models are specified, and thus selection patterns can be estimated erroneously if important variables are omitted unintentionally.Footnote 26 Therefore, a wide set of controls is indispensable so that we can estimate selection parameters and interpret them persuasively. Summary statistics appear in Table 4 in “Appendix A.4.”

Observations of refugees’ job acquisition status and market wage levels, conditional on employment, were collected 90 days after each refugee’s arrival. Such one-time, short-term records represent shortcomings of this data set.Footnote 27 However, extant labor economics literature suggests that 90 days is not too short for refugees to have found jobs (Beaman 2012; Dagnelie et al. 2019). This short term feature makes clearer how refugees, while being subsidized, made labor supply decisions with secured non-labor income, because the 90 days period falls within the period of direct, host-provided support, without exception.

3.2 Institutional context

Prior to departure to the US, newly admitted refugees receive cultural orientation, which describes the resettlement process and refugees’ rights, benefits, and obligations (Fix et al. 2017). Once they arrive, the US Department of State is responsible for initial placement and resettlement, and all approved refugees are sponsored and offered appropriate assistance by the US government (Dagnelie et al. 2019). During initial resettlement, the United States Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) provides refugees with necessities and core services, such as housing, food, medical assistance, clothing, enrollment in school, English-language classes, job training, and health screenings.Footnote 28 Through the Refugee Cash Assistance (RCA) program, refugees receive direct monthly cash subsidies, in addition to a one-time startup allowance. Depending on individual situations, they are eligible for various additional federal means-tested benefits, such as (i) special cash payments for senior citizens and adults or children with disabilities and (ii) supplementary payments for food purchases (Fix et al. 2017). Unlike other vulnerable groups, qualifying refugees can immediately apply for such means-tested assistance programs. Thus, Bardelli (2020) characterizes the refugee status as an ‘economic asset.’

Excepting the basic cash subsidy, various assistance programs are secured for several years beyond initial resettlement. For example, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), which targets low-income individuals with dependent children, supports qualifying refugees for up to five years. Supplemental Security Income (SSI) supports aged or disabled refugees for up to seven years (Fix et al. 2017). Qualifying refugees can also be supported continuously by medical assistance programs, such as Medicaid and SCHIP, for up to seven years (Bruno 2017). The food assistance program has no time limit (U.S. Government Accountability Office 2011), but as soon as a refugee becomes self-sufficient by obtaining employment, he or she no longer receives benefits.

The host-provided resettlement package, which represents non-labor income, affects how subsidized refugees make labor supply decisions. It liberates refugees from impending concerns about their livelihoods, which leads to a lack of immediate financial urgency. By virtue of such government assistance, refugees do not need to rush to obtain employment, and they can be selective in accepting job offers and keep searching for better quality jobs. This distinguishes refugees from economic migrants, who receive no host-provided assistance and must provide for themselves from the beginning. McCall (1970) argued that government benefits themselves increase refugees’ reservation wages directly, and empirical evidence supports a negative relationship between reservation wages and employment (Lancaster and Chesher 1983; Jones 1988; Addison et al. 2009; Brown and Taylor 2013). Yu et al. (2012) corroborate this aspect among North Korean refugees who resettled in South Korea.

4 Econometric methods

4.1 Selection framework

Before proceeding, I provide a primer on what a selection framework is, why it is needed in the current study, and what are the most common methods and their limitations. For brevity, detailed explanations appear in “Appendix A.2.”

4.2 Copula-based sample selection model

In economics literature, the two most common selection estimators are the bivariate maximum likelihood (ML) selection model and the Heckman two-step estimator, used widely across various applications. However, considering their limitations, detailed in “Appendix A.2,” this study uses the copula-based selection model, introduced by Smith (2003), as an econometric method that addresses how subsidized refugees select themselves into employment. According to Sklar’s theorem, any k-dimensional multivariate joint distribution can be written in terms of k univariate marginal distribution functions and a copula that describes the dependence structure among those k underlying variables (Sklar 1959).Footnote 29 More simply, the copula method couples two or more marginal cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) and generates their single joint cumulative distribution function, without assuming joint normality. Consider the canonical approach with additive error terms (Cameron and Trivedi 2005).

Selection patterns are, again, measured by the correlation of disturbances across employment and market wage equations—\(\varepsilon _{d}\) and \(\varepsilon _{w}\), respectively. For their marginal and joint cumulative distribution functions, denoted \(F(\cdot )\), coupling of a copula, C, can be expressed as:

where \(\theta \) denotes the association (or dependence) parameter between \(F_{1}(\varepsilon _{w})=u_{w}\) and \(F_{2}(\varepsilon _{d})=u_{w}\). All major notations hereafter are the same as previously defined, unless otherwise noted. If \(F_{1}(\varepsilon _{w})\) and \(F_{2}(\varepsilon _{d})\) are continuous, C is unique (Nelsen 1999). To arrive at the density of one random variable (e.g., \(\varepsilon _{w}\)) along with the cumulative probability of the other (e.g., \(\varepsilon _{d}\)), which is essential to a likelihood function, the copula method requires partial derivative of \(F(\varepsilon _{w},\varepsilon _{d})\):

where \(f_{1}(\varepsilon _{w})\) is the probability density function (PDF) of \(\varepsilon _{w}\).

Conventional in ML-based selection models,

is the starting point, which is the likelihood function for a sample-selection context (Amemiya 1985).Footnote 30 Also conventionally, N refers to the total number of observations. In (33), the component \(f(y_{w_{i}}\mid y_{d_{i}}^{*}>0)\) refers to the conditional probability density function of \(y_{w}\) given \(y_{d}^{*}>0\), which refers to the wage distribution of employed refugees \(\{i\mid D_{i}=1\}\), and its functional form can be derived as:

and using (32) for \(\frac{\partial }{\partial \varepsilon _{w}}F(\varepsilon _{w},\varepsilon _{d})\) in the last row of (35) yields:

where copula C operates as a binding mechanism. The benefit of the copula-based selection model lies in the fact that the assumption of jointly normally distributed errors can be relaxed: accordingly, the copula approach permits selection modeling based on bivariate non-normality (Smith 2003).Footnote 31 Moreover, one can flexibly apply different kinds of copulas. In addition, regarding estimation of \(\Pr [\cdot ]\) in likelihood function (36), using the copula method permits assuming any univariate distribution for the binary employment equation, further lessening restrictions on the model.Footnote 32 Further econometric details, including which copulas to use, appear in “Appendix A.3”.

5 Estimation results

5.1 Two distinct selection drivers

As Cameron and Trivedi (2005) argue, ML-based selection models permit selection on both observables and unobservables, since it permits selection on both regressors and errors in a single likelihood function.Footnote 33 Before reporting estimation results, I recap two distinct sets of selection drivers—observables and unobservables.Footnote 34 This study assesses two equations (i.e., the employment and wage equations) that are intertwined due to their dependence on common factors (Cameron and Trivedi 2005). That such common factors can be partitioned into two subcategories (i.e., measurable variables versus unobserved error terms) requires considering selection on both observables and unobservables, and it is important to note this distinction because each relates to different parameters in the copula selection model. In (36), selection on observables concerns \(\varvec{\beta }_{d}\), and selection on unobservables concerns \(\theta \) and its conversion to \(\tau \). In the following sections, estimation results of the former appear in Sect. 5.2 and those of the latter in Sect. 5.3.Footnote 35

5.2 Selection on observables

Table 1 reports estimates of selection on observables, where the dependent variable is a refugee’s employment status. In the case of logit- or probit-based single-index binary models, coefficients and marginal effects are not identical, but the ratio of coefficients for two regressors equals the ratio of their marginal effects. Conveniently, the sign of a coefficient gives the sign of its marginal effect (Cameron and Trivedi 2005),Footnote 36 and thus they are reported separately in Table 1.

Coefficient estimates appear in Columns 1 and 2 in Table 1. Since the underlying models are based on disparate link functions, the magnitudes of those coefficient estimates are not comparable directly, but their signs and statistical significance can be compared. Estimated signs and statistical significance are the same across the columns for all variables. Average marginal effect estimates appear in Columns 3 and 4 in Table 1. Marginal effect estimates are also similar across the columns for all variables, regardless of which link function was used.

One finding in Table 1 is that education does not appear to determine a refugee’s employment, a result that deviates from the common, stylized notion that education correlates strongly and positively with labor market outcomes (Borjas and Van Ours 2010). Most notably, the average marginal effect of higher education on a refugee’s employment is negative, though statistically insignificant, with secondary education used as a baseline reference. This means that refugees’ selection into employment is made negatively on higher education. A refugee’s decision of whether to enter employment depends on a comparison of market and reservation wages (i.e., \(D^{\mathrm{Employment}}=\varvec{1}[\log w^{\mathrm{m}}>\log w^{\text {r}}]\)), and thus negative selection on higher education suggests that the rate of return to tertiary education is higher in the reservation wage equation than in the market wage equation. A refugee’s college diploma appears to not be valued by employers in the US job market as much as it is by its owner as a job seeker. Considering the argument from Spence (1973) and Arrow (1973) that higher education plays a signaling role in usual labor markets, such a negative association represents a distinctive feature of refugees’ labor market. US employers’ undervaluation of refugees’ higher education accords with empirical evidence from Zeng and Xie (2004), who finds that American employers, who are generally unfamiliar with foreign universities, underrate higher education attained abroad. Chiswick and Miller (2009) points out that non-natives’ skills acquired in formal schooling tend to be less industry- and occupation-specific, and thus non-natives find that the skills they have are irrelevant to their new labor market.Footnote 37 For comparison, wage regression results, one with and the other without selection correction, appear in Table 5 in “Appendix A.4.”Footnote 38

Regarding job experience, Table 1 shows that a refugee’s home country work experience does not affect employment in the US labor market; its sign is negative, though statistically insignificant. This means that a refugee’s work experience does not function as a positive signal in host country labor markets: it appears to be underappreciated, causing negative selection on the experience variable. The reason might reside in the fact that host country employers have imperfect information on what overseas credentials mean, which, according to Chiswick and Miller (2009), leads to the less-than-perfect international transferability of foreign experience.Footnote 39 Based on these findings related to education and home country experience, refugees appear to have difficulty transferring both formal schooling and labor market experience from their country of origin to a host country, which accords with findings from Albiom et al. (2005) and Lang (2005).Footnote 40 Another reason for this negative selection concerns the possibility that those two variables correlate positively with pre-displacement personal wealth. If there is a tendency for refugees with higher education or more work experience to bring their, on average, greater pre-displacement wealth with them, and if they can rely on such carry-over wealth for resettlement, without having to start working immediately, the observed negative association is understandable in that liquidity constraints are less of an issue for them.

With regard to English, as a host country language, estimates in Table 1 accord with intuition. The highest level of English proficiency associates positively with employment, with the second highest level used as a baseline. This is unambiguous in that local language skills are vital to a refugee’s human capital in his or her resettlement region, and a host country employer can easily assess whether a job applicant’s language proficiency is sufficient. Several empirical studies corroborate a positive response of labor market outcomes to local language proficiency, such as Chiswick (1991), Dustmann and van Soest (2001), Dustmann and Fabbri (2003), Bleakley and Chin (2004), Wang and Wang (2011), Chiswick and Miller (2014), and Ferris (2020).

Another unique feature of refugees’ labor market is that administrative factors affect employment. First, participation in the Matching Grant Program substantially associates positively with employment. The program is a resettlement assistance initiative for officially accepted refugees, with the purpose of helping them gain early employment.Footnote 41 This topic is revisited in Sect. 6.1.

Second, delayed issuance of a social security number appears to greatly reduce a refugee’s employment probability, which accords with expectations.Footnote 42 All officially admitted refugees are authorized to work in the US by the Department of Homeland Security, and they receive a social security number usually within three weeks after arrival. However, sometimes there are delays, the most common cause of which, according to the US Social Security Administration and the Department of Homeland Security, is IT issues. No US federal law prohibits the hiring of a person based solely on lack of a social security number. However, federal law and regulation mandate the reporting of an employee’s taxpayer identification (e.g., social security number or taxpayer identification number) on federal returns and payee statements. Delayed issuance thus makes it more difficult for a refugee to find acceptable employment opportunities, hampering his or her selection into work. On the other hand, as discussed in Sect. 3.2, not having a social security number does not disqualify refugees from receiving host-provided resettlement benefits.

Regarding the large-family dummy variable, coded as one for those with five or more family members, its sizable, negative marginal effect estimates, reported in Table 1, do not agree with findings from extant studies. According to Hill (1971), conventional wisdom suggests a positive relationship between family size and the supply of labor—for both poor and non-poor people. This is intuitive in that the larger a person’s family, the greater the family’s financial needs, leading to a greater likelihood that the person will work. However, an opposite pattern was found among subsidized refugees. The deviation appears to derive from the fact that after arrival in the US, admitted refugees are offered various care and financial assistance by the US government. See Sect. 3.2 for details. Since the amount of host-provided cash assistance varies according to family size (i.e., larger families receive more), a large family’s financial urgency is, on average, lower. Hence, this aspect increases the reservation wages of refugees with more family members, making it more difficult for (10) to hold.Footnote 43

5.3 Selection on unobservables

Refugees are in a unique situation; they receive various host-provided care and financial assistance but are likely targets of discrimination and undervaluation in local labor markets. Given that combination of benefit and disadvantage, how refugees make their labor supply decisions is what this paper addresses, specifically in terms of wage potential. Of primary interest, then, is selection on unobservables, which, despite its importance, has not been investigated in extant studies.Footnote 44 As mentioned earlier, selection on unobservables is measured by the correlation parameter that gauges the dependence pattern between \(\varepsilon _{d}\) and \(\varepsilon _{w}\) in (30). Discussed in Sect. 2 is the supposition that unobserved human capital, s, is the only component through which the correlation of disturbances across the employment and market wage equations materializes.

In the case of the copula-based selection model, Kendall’s \(\tau \), explained in “Appendix A.3”, is the correlation parameter that must be interpreted. If \(\tau \) is zero, there is no selection on unobservables. If \(H_{0}:\tau =0\) is rejected, the sign of \({\widehat{\tau }}\) indicates in which direction \(\varepsilon _{d}\) and \(\varepsilon _{w}\) correlate. Kendall’s \(\tau \) estimates are reported in Table 2. Many studies commonly use logit and probit interchangeably, but probit is more restrictive due to its thinner tails. Nevertheless, the Heckman two-step estimator requires a probit model in the first-stage employment equation because its second-stage equation uses \(\phi (\cdot )/\Phi (\cdot )\) as a selection correction term. When using the copula-based selection model, not only probit but also logit can be used, and I exploit this flexibility. Results reported in Columns 1 through 3 of Table 2 are based on logit as a binary link function for the employment equation: those in Columns 4 through 6 are based on probit. For robust estimations, various copulas were used, such as the Gaussian, Frank (1979), and Farlie (1960)–Gumbel (1960)–Morgenstern (1956) copulas. In all six estimations, the null hypothesis of no selection on unobservables was rejected, and selection parameter, \(\tau \), was estimated negative. Hence, it can be argued that subsidized refugees select themselves negatively into employment, a finding that contradicts what is usual in conventional labor markets.

One question is what the economic explanation of \(\tau <0\) is. In short, it means that refugees with greater wage potential (stemming from a higher rate of s) are less likely to work, observable factors held constant. Negative selection into employment has been problematic and perceived as an anomalous symptom that derives from misspecification problems (Ermisch and Wright 1994). However, if the unique situation that subsidized refugees experience is considered, it is not nonsensical. This is the point at which theoretical explanations made in Sect. 2 are useful. The underlying, structural mechanism that causes \(\tau <0\) is (24), introduced in Sect. 2.1. Selection into employment is made negatively when a refugee’s self-valuation of his or her unobserved human capital is substantially larger than its payoff in the labor market. In the context of subsidized refugees, this is explainable from both \(\gamma _{\text {m}}\) and \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\) view points.

[Low market valuation] \(\gamma _{\text {m}}\) can be very low if host-country employers undervalue refugees’ unobserved capabilities and skills. Many empirical studies suggest that native versus non-native wage gaps persist in nearly all occupational fields, even when extensive observables are controlled for. For example, Smith and Fernandez (2017) found that such gaps exist even after controlling for education, literacy skills, numeracy skills, age, gender, years in a position, hours worked per week, area of study, and information and communications technology adeptness, corroborating the low \(\gamma _{\text {m}}\) set by host country employers. Thus, it can be said that local employers undervalue refugees’ unobserved skill components.

Then, what are the possible reasons for low \(\gamma _{\text {m}}\)? As Brell et al. (2020) underscore and Oreopoulos (2011) corroborates, refugees experience hostility, discrimination, and prejudice from host communities. If this is the case, more intense hostilities, at the regional level, likely lead to lower \(\gamma _{\text {m}}\), and negative selection is more pronounced. See 5.5 for an investigation of this aspect. Over and above this, Gould and Moav (2016) argue that some components of non-natives’ unobservable skills are inherently country-specific, such as personal connections, local knowledge of market conditions, and institution-specific knowhow. It is understandable that those components have near-zero returns from a host country employer’s viewpoint. Additionally, in migration literature, the skill-paradox theory explains why non-natives’ unobservable skills are devalued systematically, by which it is meant that non-natives are more likely to be targets of employment discrimination the more skilled they are (Dietz et al. 2015). According to Dietz et al. (2015), this derives partially from the fact that employers often view refugees’ skill components as a threat to locals. This aspect lowers \(\gamma _{\text {m}}\) by triggering anti-refugee sentiments in local labor markets, especially against skilled refugees.

[High and rigid non-market valuation] Among subsidized refugees, \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\) can be stuck at a level substantially greater than \(\gamma _{\text {m}}\) because refugees with secured host-provided, non-labor income are free from financial urgency and thus have no incentive to adjust their \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\) quickly to market-determined lower \(\gamma _{\text {m}}\). Recall the explanation in Sect. 2.1 that if \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\approx \gamma _{\text {m}}\), selection into employment is made positively. High, rigid \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\) is a unique facet that applies to subsidized refugees but not to economic migrants without host-provided financial subsidies.

The atypical \(\tau <0\) can also be explained by the standard job search model. Recall that a refugee’s employment status, explained in Sect. 3.1, is measured 90 days after arrival. Suppose there are two observationally identical refugees; their reservations wages differ due to a disparity in their unobserved skill components, s. As Borjas and Van Ours (2010) suggested, the one with a lower reservation wage (i.e., a lower rate of s) will find acceptable job offers more quickly. For this refugee, there must be more wage offers for which employment is an attractive option. In contrast, the other one, with a higher reservation wage (i.e., a higher rate of s), will need more time to find an acceptable job and thus is less likely to be employed by the time the measure is made. Furthermore, host-provided benefits reduce the marginal cost of a job search. Hence, the one with a higher rate of s does not have to adjust quickly his or her self-valuation \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\) while being subsidized.

5.4 Selection, workforce composition, and market wages

Discussed in Sect. 2.2, a refugee’s selection pattern affects the distribution of observed market wages. In conventional labor markets, in which selection into employment is made positively, the wage distribution of \(\{i\mid D_{i}=1\}\) is centered at a higher level in comparison to the counterfactual wage distribution of \(\{i\mid D_{i}=0\}\). However, negative selection can overturn this conventional wisdom because it means that those with a lower (higher) rate of wage potential are more (less) likely to enter employment when observable features are controlled for. Hence, if negative selection is the case, (29) holds.

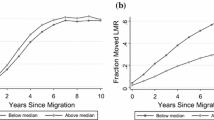

Such an overturned pattern appears in Fig. 1, which is a visual representation of (29). In Fig. 1, \(\log w_{i}^{\mathrm{m}}\) is modeled conditional on observables and interdependence between \(\varepsilon _{d}\) and \(\varepsilon _{w}\).Footnote 45 Estimates are based on the copula-based selection model with the logit link function and the Frank copula, and copula-based error dependence is captured by \({\widehat{\theta }}\) and its conversion to \({\widehat{\tau }}\), as shown in Table 2.Footnote 46 The first panel depicts \({\widehat{y}}_{w_{i}}\) among employed refugees \(\{i\mid D_{i}=1\}\), and the second depicts \({\widehat{y}}_{w_{i}}\) among non-employed refugees \(\{i\mid D_{i}=0\}\). The latter is counterfactual and thus constructed by considering the selection rule. Comparing the mean of each distribution (i.e., the dashed vertical lines in the first and second panels) suggests that selection reduces (i.e., ‘pushes down’) the wage distribution of \(\{i\mid D_{i}=1\}\) in the direction of \({\widehat{\tau }}<0\), as shown in Table 2. The third panel illustrates \({\widehat{y}}_{w_{i}}\) among all refugees, regardless of their employment status. Its mean (i.e., the solid vertical line) refers to the average wage under no selection, and it is thus used as a reference across all panels.Footnote 47

5.5 Heterogeneity in selection patterns

Findings discussed in Sect. 5.3 are based on the entire sample of observations, and the reasoning concerning \(\tau <0\) motivated further assessment into regional heterogeneity in selection patterns. Recall that the pattern of refugees’ selection into employment is determined by (i) how much local employers value refugees’ unobserved human capital when deciding on wage offers and (ii) how much refugees internally appraise it when setting their reservation wages. The latter is thought to be rigid, regardless of region, due to nationwide refugee benefit packages stipulated largely at a federal level: however, the former must depend greatly on regional characteristics—such as the degree of political conservatism, multiculturalism, and open-mindedness toward non-natives (Karreth et al. 2015). Accordingly, a logical inference is that refugees’ negative selection is greater in regions in which their unobserved human capital is devalued more severely by local employers due to greater hostility. To explore this hypothesis, I exploit that refugees are distributed exogenously across 16 resettlement cities by a refugee resettlement agency and that those resettlement cities have substantial differences regarding refugee-friendliness. Besides, refugees are not allowed to make inter-regional residential relocations during resettlement, which makes this analysis reasonable.

To assess regional heterogeneity, the 16 resettlement cities were classified into two types—‘refugee-friendly’ and ‘refugee-unfriendly.’ In doing so, each region’s friendliness to non-natives was used as a classification criterion, based on the General Social Survey (GSS) conducted in 2000, as in Shin (2021). The relevant GSS question asks whether a respondent thinks that the number of non-natives permitted to come to the US to live should decrease. Cities with above average rates of respondents saying ‘yes’ to this question were considered refugee-unfriendly, with the others considered refugee-friendly. Selection parameter, \(\tau \), was estimated separately for comparison, and the results based on the Frank copula are presented in Table 3. No matter which binary link function was used, the same findings were observed: negative selection into employment was far greater in refugee-unfriendly regions.Footnote 48 In refugee-friendly regions, in which devaluation of refugees’ unobserved human capital was expected to be less severe, negative selection was not evidenced. The same contrast is found when the Gaussian copula is used.Footnote 49

6 Robustness checks

6.1 Matching grant program

Explanations offered so far assume implicitly that refugees look for jobs with the goal of finding (acceptable) employment. Although no direct variable is available with which a refugee’s degree of job-seeking efforts can be gauged, whether a refugee participates in the Matching Grant Program (MGP), discussed in Sect. 5.2, can proxy for that aspect. For MGP participants, their active job seeking efforts are closely monitored by local resettlement agencies. A local MGP office might impose sanctions (i.e., temporarily reducing or withholding assistance and services) on an individual refugee if he or she fails to comply with an agreed-on self-sufficiency plan or repeatedly refuses to interview for jobs. Thus, MGP participants are assumed to be searching for job opportunities. Exploiting this institutional setup, additional analyses were made based on those who are MGP participants. Appearing in Tables 7 and 8 in Online Supplement B.6, estimates corroborate refugees’ negative selection into employment. However, among refugees who are not MGP participants, the the copula-based selection model fails to make its likelihood function converge, which is expected due to the much lower number of observations (\(N=619\)).Footnote 50 As an alternative, the bivariate ML selection model was applied: its selection estimate \({\widehat{\rho }}=-0.1876\) with p-value\(=0.07\) confirms negative selection into work, albeit less statistically significant.

6.2 Estimations with an exclusion restriction

When using the copula-based selection model, an exclusion restriction variable that affects employment without affecting market wages is theoretically unessential, especially when its likelihood function converges without such a variable. This is evidenced by simulation results from Marra and Wyszynski (2016). However, recent studies that use the copula-based selection model, such as Arellano and Bonhomme (2017), suggest that using an exclusion variable is beneficial from a practical perspective. A reasonable robustness check strategy was thus to compare selection estimates from two distinct models—one with an exclusion restriction variable and the other without. In doing so, a critical issue lies in whether there exists a reasonable and available exclusion restriction, say z, in the context under investigation such that \(\mathbf {x}_{d}=(\mathbf {x}_{w}^{\prime },z)^{\prime }\) in (30) holds, the point at which labor economic theories should help find z.

According to the search theory literature, reservation wages, \(w^{\mathrm{r}}\), can be expressed as:

where b represents the amount of unemployment benefits, c is job search costs, and r is the (future-to-present) discount rate. Assume that market wage offers, say \(w^{\text {m}}\), are independent realizations from a known wage offer distribution, and that they are received according to a Poisson process with parameter \(\delta \) (Addison et al. 2009). \(F(w^{q})\) for \(q\in \{\text {market (m), reservation (r)}\}\) is the cumulative q-wage distribution (Mortensen 1977). To find an exclusion restriction in the context of this study, a variable should exist that affects refugees’ reservation wages, without affecting market wage offers. Note that (37) comprises two additive terms, and only the first is free from market wages, \(w^{\text {m}}\). An exclusion restriction variable thus should be something that concerns \((b-c)\). In conventional labor markets, b is the value of unemployment benefits, but in the case of subsidized refugees, host-provided resettlement packages play the same role. However, an important difference is that the amount of b for refugees is determined by household size. Larger families receive greater subsidies, which is why the large-family dummy leads to higher reservation wages and associates negatively with employment in Table 1.Footnote 51 On the other hand, a refugee’s household size is not expected to affect his or her wage offers. Therefore, this section uses the large-family dummy as an exclusion restriction, z, when again using the copula-based selection model. Blundell et al. (2007) also use out-of-work welfare benefit as an exclusion restriction, based on the same reasoning. However, one caveat is that the absence of z in the market wage equation is difficult, if not impossible, to test.Footnote 52

Selection estimates without z appear in Table 2 in Sect. 5.3, and those with z appear in Tables 9 and 10 in Online supplement B.6. The same patterns were observed during both analyses, corroborating subsidized refugees’ negative selection into employment.

6.3 Heckman two-step selection model

Since copula-based estimates are sensitive to the choice of copula, various copulas were used in Sects. 5.3 and 6.2. Nevertheless, this limitation requires robustness checks based on other estimators. Although conceptually ideal, semi- and nonparametric approaches do not allow direct estimations of the error correlation (Genius and Strazzera 2008).Footnote 53 If there is a variable can be used as a reliable exclusion restriction, the Heckman two-step estimator is useful for checking the robustness of selection estimates obtained from the copula-based selection model because the Heckman two-step estimator is also free from the restrictive joint normality assumption of \(\varepsilon _{d}\) and \(\varepsilon _{w}\) in (30). It requires only the first-stage marginal normality \(\varepsilon _{d_{i}}\sim N(0,\sigma _{\varepsilon _{d}}^{2})\) and linearity of the conditional expectation of error terms \(\mathbb {E}(\varepsilon _{w}\mid \varepsilon _{d})=\delta \varepsilon _{d}\) (Lee 2009; Montes-Rojas 2011). This section thus uses the Heckman two-step estimator, with the same exclusion restriction variable discussed in Sect. 6.2. In using the Heckman two-step estimator, its limitations explained in “Appendix 4.1,” should be considered carefully.

The Heckman-version \(\rho \) estimate appears in Table 11 in Online supplement B.6. As shown therein, the Heckman-version \(\rho \) was estimated negative, although its statistical significance is valid only at the 10 percent level, which is understandable since the loss of efficiency caused by using the Heckman two-step estimator is often great (Leung and Yu 1996; Stolzenberg and Relles 1997; Moffitt 1999; Puhani 2000; Bushway et al. 2007). \({\widehat{\tau }}<0\) in Table 2 and \({\widehat{\rho }}<0\) in Table 11 lead to the same economic explanation that subsidized refugees select themselves negatively into work.Footnote 54

6.4 External shock and reversed selection

If interpretations and reasoning discussed so far are correct, a decrease in \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\) should cause a refugee behavioral change and overturn their selection pattern, thus reversing the initial situation in which refugees with a higher rate of s are less likely to work (i.e., negative selection) to a situation in which such refugees are more likely to work (i.e., positive selection).Footnote 55 Recall that \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\) measures the degree to which refugees evaluate the value (or price) of their unobserved skill components s when deciding on their reservation wages. Thus, \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\) is sensitive to how job-seeking refugees perceive external labor market conditions. Refugees’ expectations of future labor market outcomes, influenced heavily by market conditions, can affect \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\) through the process of adjusting their reservation wages.Footnote 56 In previous sections, \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\) was considered rigid because host-provided refugee benefits are secured for substantial periods. Nevertheless, refugees are aware that the benefits taper over time, which means they will experience a liquidity constraint at some point.Footnote 57 Therefore, if sufficiently large to intimidate job-seeking refugees, a negative labor market shock can make them perceive high uncertainty and cause a large decrease to \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\).

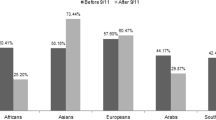

Considering this, the current section exploits the fact that the data set includes data from late-2001 to 2002, during which a massive demand-side negative shock occurred to non-natives in the US labor market—the 9/11 terrorist attacks.Footnote 58 Many empirical studies corroborate that the 9/11 attacks had negative influences on labor market outcomes among non-natives in the US, such as Dávila and Mora (2005), Kaushal et al. (2007), and Shin (2021). As a huge adverse shock, the 9/11 attacks might have lowered \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\) insomuch that \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\approx \gamma _{\text {m}}\) holds. If so, the theoretical model predicts selection into employment to be made positively, as discussed in Section 2.1. Therefore, a reasonable hypothesis is that refugees’ selection pattern reversed immediately after the 9/11 attacks—from pre-shock negative to post-shock positive.

To assess this hypothesis, selection parameters were estimated separately for each of three periods: (i) January to August 2001 (i.e., before the 9/11 attacks), (ii) the same months during 2002, and (iii) those during 2003. Due to the much-reduced number of observations in each sub-sample, copula-based likelihood functions failed to converge. Thus, the Heckman two-step estimator was used with the exclusion restriction explained in Section 6.3. When using the Heckman two-step estimator, the same caveats discussed earlier apply. Summarized graphically in Fig. 2, estimation results accord with the reasoning discussed above; negative selection was much more pronounced before the 9/11 attacks, but in contrast, immediately after the attacks, selection patterns appear to have reversed from negative to positive. Over time and with influences deriving from the shock diluted, selection appears to have returned to negative during 2003.Footnote 59

According to discussions so far, the post-shock reversed selection during 2002 was predictable; it is a natural inference that the 9/11 attacks, which represent a huge adverse shock, made refugees in the US realize quickly the harsh job market situation and accordingly adjust their expectations and reservation wages, leading to a decrease in \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\). Due to the unfavorable market situation, refugees, although they perceived that their skills were discounted, could not afford to use a wait-and-see job-seeking strategy. According to Schüller (2016), the 9/11 attacks caused an immediate shift to more negative attitudes toward non-natives. Thus, the attacks might have induced a substantial increase to anti-refugee rhetoric among local employers, lowering \(\gamma _{\text {m}}\) in market wages accordingly. Nonetheless, assuming that \(\gamma _{\text {m}}\) was already low, even before the attacks, \(\gamma _{\text {r}}\) must have been lowered more, which caused reversed selection. Despite these empirical findings, statistical non-significance of \({\widehat{\rho }}_{2002}\) and \({\widehat{\rho }}_{2003}\) in Fig. 2 requires further studies using more observations.

7 Conclusion

Despite increasing importance of refugee-related topics, little attention has been paid to how refugees, while receiving host-provided care, select themselves into employment. This paper is first to address such an important question: in doing so, it considers fundamental econometric limitations of common selection estimators and thus uses a copula selection model. For robust estimations, various copulas were used, along with household size, as a generally agreed exclusion restriction variable. All estimates calculated in this study, regardless of the choice of link functions and copulas, and the use of an exclusion restriction, suggest that subsidized refugees select themselves into employment negatively.

In labor economics literature, the common wisdom suggests positive selection because it is more costly for high-potential people to remain out of work. Hence, negative selection into employment has been considered confusing, viewed as an abnormal symptom caused by misspecification. However, negative selection need not always be considered nonsensical, and the simple theoretical model discussed in this paper explains why it is understandable in the context of subsidized refugees. The core of the matter is comparing two price parameters of refugees’ unobserved human capital—market valuation versus non-market self-valuation. Selection into employment is made negatively when the former is substantially lower than the latter, which is thought to be rigid.

Negative selection should be treated as a warning to host governments, most importantly because it reduces the conditional mean of the observed market wage distribution. It also indicates the possibility that the refugee workforce composition is less productive, and that refugees’ (discounted) skill components are being wasted, causing human capital losses to host societies. To counterbalance losses incurred from negative selection, those not in early employment should find better jobs, from a long-term perspective. However, this is not guaranteed; rather, it is argued that early employment provides refugees with some progression (as a stepping stone) toward better jobs in labor markets (Arendt 2020).

Findings from this study provide new understanding of how newly arrived, subsidized refugees make labor supply decisions, and the explanations above make several contributions to literature on job-seeking refugees. Due to the cross-sectional feature of the data, however, this study cannot further address the question of how selection patterns change as the termination of host-provided support nears. It only investigates the short-term perspective of refugees’ employment decisions. Thus, the expression subsidized refugees is used throughout the paper to imply that results cannot be generalized to non-subsidized refugees and long-term employment decisions. Since the theoretical model points to the hypothesis that refugees’ selection into work shifts gradually from negative to positive as benefits and subsidies taper, future research should consider long-term perspectives by using panel data with multiple observation points.

Notes

Parsons and Vézina (2018) highlight that refugee integration increases subsequent exports to their country of origin.

Throughout this paper, selection, as an economic term, refers to selection on unobservables unless otherwise specified. Likewise, if not otherwise mentioned, it is assumed that observable factors are held constant. More details are discussed in Sect. 2.

The question of how migrants, who should be distinguished from refugees for reasons addressed below, select themselves into migration (and return migration) has been investigated in many studies, such as Borjas (1987), Chiquiar and Hanson (2005), Rooth and Saarela (2007), Moraga (2011), Wahba (2015), and Borjas et al. (2019). A brief explanation of these studies is given in Online supplement B.2.

Some qualified host populations receive unemployment benefits. However, the duration of such benefits is 26 weeks across most of the US (though 28 weeks in Montana and 30 weeks in Massachusetts), which is much shorter than the average duration of the refugee subsidy program.

The expression not fully explained by \(\mathbf {h}\) is used intentionally because we cannot rule out the possibility that \(\text {Cov}(\mathbf {h},v)\ne 0\) (e.g., observable schooling and unobservable abilities).

To the extent that \(v_{\text {m}_{i}}\) is unmeasured, its influences on \(\log w_{i}^{\mathrm{m}}\) are recognized as an increase (or decrease) in a refugee’s wage, conditional on his or her observed (productivity and demographic) characteristics \(\mathbf {z}\).

Many empirical studies corroborate the importance of capabilities and skills that are commonly unobserved but substantially affect wages, such as Murnane et al. (1995), Neal and Johnson (1996), Kuhn and Weinberger (2005), Heckman et al. (2006), and Fortin (2008). Some investigations, such as Mulligan and Rubinstein (2008), use test scores or IQ data as proxies for unobserved abilities.

Other papers, such as Taber (2001), also use the same distributional assumption \(s\sim N(\mu _{s},\sigma _{\varepsilon _{s}}^{2})\).

Borjas et al. (2019) simply call it ‘(unobserved) skill component.’

\(\varepsilon _{q}\) for \(q\in \{\text {r},\text {m}\}\) is conceptually important when expecting an exclusion restriction to exist.

Controlling for a broad set of observables might also control for some unobservables to the degree that they correlate.

The richness of

and

and  in the current study is detailed in Sect. 3.

in the current study is detailed in Sect. 3.The bivariate normality of

enables

enables  to be normally distributed with its constant variance

to be normally distributed with its constant variance  . Thus, the probit link function can be used.

. Thus, the probit link function can be used.Similarly, Lang (2005) attributes low \(\gamma _{\text {m}}\) to ‘zero-return’ on non-native workers’ imported labor market experience.

This section partly draws from Shin (2021), which is based on the same data set.

This data set is initially used in Beaman (2012), in which some network-related variables are newly collected.

For all sampled refugees, their claims were decided before arrival in the US. They thus had permission to work immediately after arrival in resettlement cities.

For more details, see Brell et al. (2020).

For an overview of issues related to the economics of immigration, see Borjas (1994).

For further discussions on selectivity, see Online supplement B.4.

This contrasts with the case of reunification refugees who have personal sponsorship (Tran and Lara-García 2020).

Potocky-Tripodi (2004) avoids this bias by using several variables such as (i) the number of relatives living in the same city or county, (ii) the number of relatives living in the US but not in the same city or county, and (iii) how much help a refugee received from relatives after arrival in the US.

The more observables we can control, the more likely (6) holds.

Another disadvantage of this data set is that it comprises only male refugees. For more discussion, see Online supplement B.5.

Admitted refugees begin receiving such services immediately after arrival, even before social security numbers are issued.

Thus, all multivariate distributions have a copula representation.

ML is an abbreviation for maximum likelihood.

Specifying two marginal distributions separately is much less restrictive than specifying their joint distribution.

Although the probit and logit models are largely undifferentiated, the tail feature of each can differ substantially, and the latter is known to be more robust due to its thicker tails.

In economics literature, ML-based selection models are often referred to as models of selection on unobservables, with selection on observables implicit (Cameron and Trivedi 2005).

Considering the former is simpler—including regressors and estimating their coefficients (or marginal effects). In many labor supply contexts, however, errors can still correlate, even when observable regressors are controlled for, leading to the latter (Cameron and Trivedi 2005).

Discussed in Sect. 1, this study assesses whether unobservable human capital factors that raise the wage a refugee receives during employment increase (or decrease) the probability that he or she enters employment, which has not been investigated. Thus, selection on unobservables is of more interest in the current paper.

This is intuitive because \(F_{\text {C.D.F.}}^{\prime }(\cdot )>0\) holds for both the probit and logit models.

Vocational school graduates associate with (statistically nonsignificant but) substantially higher employment probabilities, which is understandable because training and knowledge obtained in vocational schools in home countries might transfer (relatively) easily to the US labor market.

Note the positive roles of higher education on wage levels, which accords with our intuition.

Lang (2005) expresses this as ‘zero-return on imported experience.’

According to Albiom et al. (2005) in Canada, the financial value of foreign work experience is about 30 percent of that of Canadian work experience, and foreign education is valued at about 70 percent of Canadian education.

The most important component of the program is its employment services, which comprise English-language training, ongoing networking, pre-employment training, job readiness workshops, employer-specific training, short-term vocational training, employer-employee matching, certification or re-certification for professional or paraprofessional refugees, and post-placement support. For details, see Shin (2022).

Social security numbers are used to report a person’s wage to the government and to determine a person’s eligibility for social security benefits.

The negative relationship between non-labor income and labor supply is already well established. See Heineke and Block (1973).

In the context of migrants, Borjas et al. (2019) underscore the importance of unobserved abilities as drivers of selection.

This corresponds to Column 2 in Table 2.

Mathematically, the third panel distribution is centered at the weighted average \(\Pr (D=1)\cdot \mathbb {E}(y_{w}\mid \mathbf {x}_{w},D=1)+\Pr (D=0)\cdot \mathbb {E}(y_{w}\mid \mathbf {x}_{w},D=0),\) the sample estimate of which is simply \(N^{-1}(\sum _{i\in \{i\mid D_{i}=1\}}{\widehat{y}}_{w_{i}}+\sum _{i\in \{i\mid D_{i}=0\}}{\widehat{y}}_{w_{i}}).\)

Statistical significance at the 10 percent level is expectable due to the smaller number of observations.

See Table 6 in Online supplement B.6 .

Addison et al. (2009) also argue that higher unemployment benefits lead to higher reservation wages, based on cross-country data.

Recent studies suggest that the number of family members can also affect efforts at marketplace work, and thus productivity and wages (Dolado et al. 2020).

For an example, see D’Haultfoeuille et al. (2018).

\(\tau \) from the copula-based selection model and \(\rho \) from the Heckman two-step estimator cannot be compared directly regarding magnitude because each is based on different metrics (Gilpin 1993; Nelsen 1999). Nevertheless, their empirical meanings are the same, and their signs can be compared directly, which is of primary interest for a robustness check (Xu et al. 2013).

Mulligan and Rubinstein (2008) demonstrate this in the context of females’ labor force participation.

Brown and Taylor (2013) theorizes that expectations play a role in adjusting reservation wages.

It is expected that negative selection gradually vanishes as host-provided assistance tapers. Therefore, refugees’ selection into work is expected to shift from (initially) negative to (ultimately) positive.

The 9/11 attacks, the deadliest terrorist attacks in America, were a series of airline hijackings and suicide attacks perpetrated by 19 militants who associated with Al-Qaeda against targets in the US.

These results accord with findings from Dolado et al. (2020), in which it is shown that massive job destruction that derives from a negative shift in labor demand (e.g., economic recessions) can cause the pattern of selection into employment to become more positive (i.e., equivalently, less negative). The 9/11 attacks represent another typical example of a huge demand-side negative shock, and I likewise observe an upward change in Fig. 2. Dolado et al. (2020) show that shock-driven changes in selection return to their pre-shock patterns during the subsequent recovery phase, which also accords with Fig. 2.

This paper uses non-employed instead of unemployed because the definition of the former includes potential workers who choose not to (immediately) enter employment (Murphy and Topel 1997).