Abstract

Throughout the world, lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans*, intersex, and queer (LGBTIQ+) self-identification has significantly risen among Millennials and Generation Z. However, many studies have overlooked how sexual identity and fluidity among young people are potentially endogenous to ideology, as a psychological and political factor, as well as gender and generational cohorts. This article explores these issues among 4,000 Catalan Millennials and Gen Z individuals using data from two official surveys conducted in 2017 and 2022. Our findings indicate a rise in non-normative sexual orientations and a shift towards more fluid conceptions of sexuality, rather than fixed categories, with notable variations based on gender and ideological stance. Nonetheless, we observe that a leftist ideology is associated with a higher likelihood of identifying as LGB+, particularly among Catalan Gen Z women, where over 25% identify as non-heterosexual. On the one hand, this study provides a new theoretical and empirical perspective on youth sexual identity outside the Anglosphere, highlighting the interplay between individual, micro psychological agency and broader, macro sociological factors, such as gender norms and political trends. On the other hand, the article offers evidence of reverse causality between sexual identity and ideology in the line suggested by Critical Theory, thus contributing to political behavior literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans*, intersex, and queer (LGBTIQ+) identities have soared in recent decades, particularly among younger generations. According to IPSOS (2023), Generation Z (born between 1997 and 2012) and Millennials (born between 1981 and 1996) are the most sexually fluid generation across thirty countries with non-exclusive identifications (i.e., bisexuality and pansexuality) clearly outpacing lesbian and gay labels. The increasing visibility of LGBTIQ + role models in popular culture and social media (Ayoub & Garretson, 2017) alongside the connection between evolving attitudes, social norms, and socially liberal same-sex legislation (Abou-Chadi & Finnigan, 2019; Tankard & Paluck, 2017) appear to be the drivers of this trend. In turn, the growing identification of younger generations with sexual minorities has been construed (and weaponized) by conservative and reactionary elements in Western and Eastern countries as a sign of the erosion of traditional Christian values.

LGBTIQ + youth identities literature indicates that younger generations are more likely to identify as sexually fluid in a “post-gay” era embedded in individualist neoliberalism, which suggests that fluidity emerges from the assimilation and commercialization of dissident sexual identities (Duggan, 2012; Ghaziani, 2011). While theoretically cogent, this vision construes the mainstreaming of non-normative sexualities as a depoliticization of the still dangerous and radical venture of coming out as a sexual and gender minority. Although the neoliberal context may influence young people’s sexual identification, it should not be only seen as a consequence of the assimilation and individualization of sexual politics, as this effectively disregards the importance of the politics of visibility to advance LGBTIQ + rights in the Global North (Michelson, 2019) and the importance of the self’s agency in navigating gendered and sexed cultural and social norms (Butler, 1990, 2002). Overall, the present account of LGBTIQ + youth identities neglects the impact of both micro, individual and social, contextual factors (Egan, 2012).

How and why does ideology impact the identification as sexual minorities among youth across gender and ideology? We investigate this question with a novel, compiled survey dataset on Catalan Generation Z and Millennials that includes sexual orientation self-labeling and ideological positioning. This study aims to fill the research gap of the relationship between micro and macro socio-political factors on sexual identity by examining the role of leftist ideology in shaping LGB + self-identification among young people in Catalonia, which outpace genetic explanations (Diamond, 2021). Our argument defends that the increasing overlap of social and political identities (Egan, 2012; Mason, 2016, 2018) has increasingly aligned sexual identities with other social markers. This is particularly relevant for young women, who may experience intersecting pressures related to gender and sexuality.

In order to test this latter proposition, the Catalan case represents a strong evaluation of our argument linking socio-political processes with sexual labeling. To start, Catalonia became the first territory in Spain and one of the first regions in Europe where same-sex unions existed as legislation as early as 1997. Besides, Catalonia approved one of the first comprehensive LGBTIQ + anti-discrimination laws in Spain in 2014, and Catalan LGBTIQ + activism spearheaded the wave of protests and organizational coordination to roll back homophobic and transphobic legislation at the national level in Spain (Calvo, 2017). Additionally, partisan competition dynamics in Catalonia and Spain have prompted political clashes around central feminist tenets such as consent (Law “Solo Sí és Sí”) and trans rights (LGBTI Law) that have reinforced the salience of LGBTIQ + and feminist demands. Lastly but crucial to the case, Catalonia presents an extraordinary overlap between redistribution, nationalist and socio-cultural issues (León et al., 2022) that convert ideology into another potential social marker.

This article presents a major innovation in the literature of LGBTIQ + identity among youth. Drawing on an intersectional perspective that relates gender, sexual orientation, generational cohort and ideology, we provide a comprehensive explanation on LGB + identification among Generation Z and Millennials that integrates Political Science and Social Psychology literature. As our main finding, we report evidence that leftist ideology drives LGB + self-labeling with gender and generation moderating the impact - young women align their sexuality to their politics more than men. Methodologically, our empirical findings are robust to a set of relevant socio-demographic covariates in regression analyses which greatly enhance the validity of our descriptive results. Finally, this contribution enriches the previous literature by examining the state-of-the-art in a Southern European country politically, culturally, and socially different from the Anglosphere and Western European areas, where most research on this topic is conducted (Dhoest, 2022). In this fashion, we expand the external validity of previous empirical and theoretical accounts regarding LGBTIQ + identification among youth.

The research paper is structured as follows. First, we examine the literature on recent shifts in young people’s sexual identification and propose a theoretical framework that integrates generational cohort, gender and ideology as explanatory variables of sexual self-identification. Second, we detail the datasets and methodologies employed to examine our hypotheses. Third, we analyze descriptive and regression results, and their literature. We conclude by offering some final remarks on the relevance of the present research and its implications for the broader literature on LGBTIQ + identification among younger generations in the contemporary Western world.

Literature Review

Shifts in Young People’s Sexual Identification

Recent research shows a change of tendency in youth in relation to their sexual orientation. Several authors have shown, both qualitatively and quantitatively, that there is an increasing visibility and acceptance of same-sex sexuality in youth (Coleman-Fountain, 2014). The use of generational categorizations, starting with Manheim’s theorization (1952), has been seen as a useful way of studying how historical context conditions the experiences and attitudes of different cohorts. Even if it has also been pointed out that there is a need of using queer frameworks, such as “queer generations”, to highlight individual differences and question homogenous generational labels (Marshall et al., 2019), studies on LGTBI attitudes have used such categorizations as a way of identifying age-related differences in relation to sexual orientation (Bishop et al., 2020; Bitterman & Hess, 2021; Dhoest, 2022; Hammack et al., 2018; Moskowitz et al., 2022; Vaccaro, 2009).

Most research on these issues focuses on the US and other English-language countries such as the UK (Coleman-Fountain, 2014) and Australia (Grant & Nash, 2020), with recent examples of European regions such as Flandes (Dhoest, 2022). Taking into account that findings are situated in Western countries and that approaches to youth sexualities should be situated in relation to specific cultural and social contexts, there are some trends that are found in these contexts. One of the main findings in relation to youth (Generation Z and Millennials) is that there is a tendency of more fluidity in relation to labels (Callis, 2014; Grant & Nash, 2020; Katz-Wise, 2015) and that younger generations are more likely to identify as bisexual or queer than to identify as lesbian or gay (Russell et al., 2009). In this sense, traditional sexual identifications are leaving space to more fluid conceptions of sexuality, which implies a questioning of labels and alternative uses of them.

The causes of these shifts in sexual identity are multiple. One of the central elements is the identification of neoliberalism as a key governmentality strategy in relation to contemporary sexuality politics (Duggan, 2012). Sexuality politics delineates the regime of truth where power and knowledge intersect to confer asymmetric status to a myriad of sexual identities. Ghaziani (2011), for example, argues that in the “post-gay era” in the US, oneself definition goes beyond sexuality and that gay people are assimilated in the mainstream, with an increase of internal diversification on LGBT + communities. Hammack et al. (2018) examine gay men’s health in the US from a life course perspective and argue that, for younger generations, legal advances on LGBT + rights have had an impact on how they conceive their sexual identities. Grant and Nash (2020) focus on bisexual and queer young women in rural Australia and argue that, although neoliberalism encourages an individualist rejection of labels, rural women’s lived experiences show how sexuality labels are also meaningful for them while they navigate homonormativity.

At the macro level, Political Science literature has found that marriage equality benefits attitudes towards lesbians and gays in Europe (Abou-Chadi & Finnigan, 2019) and the relaxation of social norms towards homosexuality after the U.S. Supreme Court ruling on marriage equality (Tankard & Paluck, 2017). Alongside the emergence of popular LGBTIQ + role models in social media and popular culture (Ayoub & Garretson, 2017), LGBTIQ + rights legislation has contributed to de-stigmatize non-heterosexual practices among younger generations. Altogether, it could be expected that younger generations will be socialized in a more welcoming environment to self-express as non-heterosexual, and they will do so in a manner that emphasizes non-exclusivity (i.e. bisexuality).

Sexuality and Gender

Sexual fluidity is a complex phenomenon that operates differently among men and women, as noted by Diamond (2008, 2014, 2016). International studies have highlighted the presence of fluidity in same-sex sexuality (Diamond et al., 2017), with a higher prevalence of bisexual/non-exclusive attraction preferences among women compared to men. Moreover, diachronic changes in social norms have led to an increase in the number of individuals identifying as having same-sex sexuality. However, two important factors need to be considered: (1) Changes in attraction over a lifespan, and (2) The flexibility of individuals engaging in same-sex behavior without identifying with non-heterosexual sexualities. While this phenomenon seems to be more pronounced among women, gender differences are challenging to ascertain conclusively (Diamond, 2008, 2014, 2016). Diamond (2014) argues against the notion that men’s sexuality is rigid and categorical, while women’s is fluid and variable. Instead, variability appears to be a common feature among individuals of both genders. Conversely, Bailey (2009) suggests that men’s sexuality is more stable across time.

The heightened role of socialization to determine sexual orientation in women is crucial because of two twin phenomena in the West. The shift in social norms and attitudes due to LGBTIQ + rights legislation combined with the increasing visibility of LGBTIQ + role models should have a stronger impact on women. In this line, Massey et al. (2021) find that the introduction of second and third-wave feminism into popular culture has empowered women to contest compulsive heterosexuality vis-à-vis men, who have not experienced an overhaul of structural hegemonic masculinity (Kaufman, 2019; Kimmel, 2013, as quoted in Massey et al., 2021). In this sense, gender differences also extend to public attitudes held toward both homosexuality and bisexuality, with men holding (Morgenroth et al., 2022). Critically, male bisexuality is associated as closer to gayness than female bisexuality to lesbianism (Herlein, Hartwell, & Munns, 2016).

Ideology, Sexuality, and Gender

LGBTIQ + Political Science literature has largely established that sexual minorities are ideologically more liberal and more likely to support socially liberal parties more often than heterosexual individuals (Egan, 2012, 2020; Kauffman & Beauvais, 2022; Turnbull-Dugarte, 2020). In Spain, LGB + individuals are more politically active, positioned to the left, and more likely to vote for socially liberal parties (Ramírez Dueñas, 2022b; Ramírez Dueñas et al., 2023), regardless of the operationalization employed (Ramírez Dueñas, 2022a). Four mechanisms explain why LGB + individuals tend to identify as liberal: selection, embeddedness, conversion, and the tailoring of liberal party manifestos to LGB + demands. Additionally, LGB + individuals often hold more liberal views on gender issues, making them more likely to align with feminist principles (Schnabel, 2018). This alignment is influenced by their unique socialization as sexual minorities, which provides a distinct perspective on gender and immigration issues (Turnbull-Dugarte, 2021).

Additionally, LGB + individuals are generally more liberal and less sexist in their views on gender issues (Schnabel, 2018). Still, they are not a monolithic block - lesbian, gay and bisexual individuals experience “gendered sexualities” (Swank, 2018a) that make them more aware of sexism (Grollman, 2017, as quoted in Swank, 2018a). For instance, in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Swank (2018a) finds that lesbian and bisexual women alongside gay men were the staunchest supporters of Hillary Clinton in clear contrast with heterosexual men. In turn, feminist scholars underscore that lesbian women are more liberal than gay or bisexual men, and more likely than heterosexual women to participate in feminist activism (Friedman & Ayres, 2013). Still, some recent research has suggested that there may be no significant difference in involvement in women’s rights between LGB + and heterosexual individuals (Swank, 2018b).

Classical Political Science views partisanship as a source of social identity (Campbell et al., 1960). In the US, political affiliation and belief systems have become significant social labels, leading individuals to align their social identity with their political beliefs (Egan, 2020). Mason (2016, 2018) highlights the concept of “social sorting,” where political identities become intertwined with other social identities, such as race, religion, and sexuality. This sorting reinforces political divisions and strengthens the alignment between an individual’s social and political identities. For politicized identities to develop, partisanship must be a prominent social identity, and political groups must have distinct characteristics in terms of “fixed” social identities. The nationwide battles over marriage equality in the US have reinforced political divisions based on race, ethnicity, and sexuality, creating an environment conducive to politicized identity shifting (Egan, 2020).

Ideology serves as a crucial lens through which individuals understand and navigate their social world. It reflects “psychological needs, motives, and orientations towards the world” (Carney et al., 2008, p. 807), offering a framework that shapes perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. Leftist individuals often possess personality traits that facilitate coming out as LGB+, such as openness to experience (Allen & Robson, 2020). This openness not only encourages self-exploration and authenticity but also fosters a greater acceptance of diverse sexual orientations and gender identities.

Moreover, ideology plays a significant role in shaping attitudes towards social justice issues. Leftist ideologies emphasize equality, human rights, and the dismantling of oppressive structures. This alignment with social justice principles makes feminist discourse particularly resonant for young women, who may experience the intersecting pressures of patriarchy and heteronormativity. As women navigate these social structures, leftist ideology provides a supportive framework that validates their experiences and promotes their rights, making them more likely to identify as LGB+. The rigidity-of-the-right thesis by Adorno et al. (1950) further elucidates the connection between ideology and sexual identity. According to this thesis, conservative ideologies are associated with psychological rigidity, resistance to change, and a preference for order and tradition (Jost, 2021). This rigidity contrasts with the openness and flexibility associated with liberal ideologies. Consequently, individuals with conservative ideologies may find it more challenging to accept non-heteronormative identities, leading to lower rates of LGB + identification among conservatives. Conversely, the ideological extremes theory (Greenberg & Jonas, 2003) suggests that ideological left and right extremes are equally characterized by mental rigidity patterns (Jost, 2021), which would make Center-Left to Center-Right individuals the most open to alternative and/or fluid sexual identities.

Ideology as Social Identities

Barber and Pope (2019) argue that ideological identities have become primary sources of social identity, rivaling traditional identifiers such as race, religion, and nationality. Ideological identities provide individuals with a sense of belonging and a framework for interpreting their social world. This conceptualization is echoed by Jost (2021), who posits that ideology reflects deeply held psychological needs and motives, shaping how individuals perceive themselves and others. Yeung and Quek (2024) build on this understanding, highlighting how ideological identities have become intertwined with other social identities, reinforcing political polarization and social sorting. They argue that ideological identification is not merely a reflection of political beliefs but a core component of individual identity that influences behavior, social networks, and attitudes towards outgroups.

The integration of ideological identities into broader social identities helps explain the strong alignment between sexual minority status and liberal ideology. For LGB + individuals, identifying with a liberal ideology provides a supportive community and a framework that validates their experiences and challenges heteronormative and patriarchal structures. This alignment is particularly salient for young women, who may face intersecting pressures related to gender and sexuality. Liberal ideology, with its emphasis on social justice and equality, offers a coherent belief system that supports their identity and activism.

In conclusion, the interplay of ideology, gender, and generation significantly impacts LGB + self-identification among youth. Leftist ideology, characterized by openness and a propensity for social justice, fosters an environment conducive to sexual identity fluidity, particularly among young women, whereas hypermasculine men tend to support radical right options (Coffee et al., 2023). This theoretical framework integrates Political Science and Social Psychology to offer a comprehensive understanding of LGB + identification among Generation Z and Millennials in Catalonia. The incorporation of Mason’s (2016, 2018) concept of social sorting and the idea of ideological identities as primary social identities from Barber and Pope (2019) and Jost (2021) underscores the pivotal role of ideology in shaping sexual identity.

H1.1

- Generation Z individuals are more likely to identify as LGB + in comparison to Millennials.

H1.2

- Generation Z individuals are more likely to identify as sexually fluid in comparison to Millennials.

H2

- Women are more likely than men to identify as LGB+.

H3.1

- Leftist individuals are more likely to identify as LGB + than centrist and rightist individuals.

H3.2

- Leftist ideology is more likely to engender LGB + identification in young women than young men.

Methodology

Data

The collection of individual-level data on the self-reported sexual orientation and ideology of Catalan youth comes from the integration of two different surveys from Catalonia. We draw on two Youth Surveys carried out by the Catalan government in 2017 and 2022 (in Catalan, Enquesta a la Joventut de Catalunya). The original datasets include Catalan 15–34 years old randomly sampled, stratified by local administrative divisions and the size of the respondent’s hometown (Serracant, 2018; Verd et al., 2022). Interviews were carried out either face-to-face or online, depending on the election of the interviewed individual. We take these stratifying variables and the post-stratification weights into account in our analysis when analyzing the descriptive results and regression results. In total, 7,088 Catalan Youth were interviewed, which represent a large-N to explore our hypotheses.

In the 2022 survey, categorical age groups are summed according to their generational cohort - Millennials (born between 1981 and 1996) and Generation Z (born between 1997 and 2012). We carry out the same operationalization for the 2017 sample with age as a continuous variable, declaring missing values of all of the individuals born before 1981. The total number of observations rises up to 3,970 individuals with all variables of interest complete, thus generating novel and unique sample data of sexual orientation self-identification in Southern Europe to carry out descriptive and regression analyses.

Dependent and Independent Variables

Departing from the outlined hypotheses, our main dependent variable is the self-reported sexual orientation of Catalan Millennials and Generation Z individuals. The operationalization of LGB + sexual identities follows the seminal work on LGB + political behavior in the United States of Hertzog (1996), which subsequent works have consistently followed in the United States, Canada and Europe (Egan, 2008; Guntermann & Beauvais, 2022; Hunklinger & Kleer, 2024; Page & Paulin, 2022; Wurthmann, 2023). Survey inquires about sexual identity by asking “Can you tell us which is your sexual orientation?” with the categories of (1) heterosexual, (2) bisexual, (3) lesbian/gay, (4) questioning, and (5) other. Alternative sexual identities of other and don’t know/don’t answer responses, are included in the statistical models to increase the N of their study but their coefficients and models are not reported due to the low reliability of statistical results resulting from their small subsample size.

Self-reported ideology is the traditional measure to address ideologies as social identities (Barber & Pope, 2019; Jost, 2021, as quoted in Yeung & Quek, 2024). In this latter sense, the ideology construct goes beyond the strictly (institutionally) political to also encompass psychological elements (Jost, 2021). The survey questions ask “When people talk about politics, left and right are usually employed. How do you define yourself? As…”. Our operationalization converts ideology into a categorical variable with three groups − (1) Left, (2) Center, and (3) Right. We recode the categorical variable in both Youth Catalan surveys by joining the Far-Left, Left and Center-Left into the (1) Left, Center to (2) Center, and Center-Right, Right and Far-Right to (3) Right. Even though we would like to keep the original values as they are, we collapse categories in order to ensure that our results are representative provided the low number of observations for sexual minorities.

Sexuality across Groups

In order to test the detailed hypotheses, we draw on generations and sex-gender binary categorizations between (1) Men and (2) Women. Unfortunately, we cannot rely on self-reported gender identity data because it is only available in the second Catalan survey.

Methods

We initially offer a brief descriptive analysis of self-identified sexuality across youth generations broken by gender and self-identified sexuality across youth generations broken by ideology. We further buttress our analysis with the application of regression analysis to better capture the bidirectional relationship between ideology and sexual orientation. Multinomial logistic regressions are employed to assess the causal relationship between ideology and sexual orientation, and vice versa, controlling for a set of relevant indicators. The first set of regression models assesses the relationship between sexuality as the driver of ideology, while the second one examines whether ideology drives sexuality.

In order to better isolate the effect of the independent variables in the first set of models, we control for education level as it has been demonstrated that college environments offer a safe space for individuals to explore and reaffirm their sexual orientation (Haltom & Ratcliff, 2021). Categories are (1) Basic education (no education to early secondary education), (2) Secondary education (advanced secondary education), and (3) Tertiary education (undergraduate degree in university to Doctoral degree). Besides this, we also control for the subjective identification of social class, as well as the objective income status of the respondent to assess ideology identification. To better calibrate the approximate impact of ideology on sexual identity, we control whether the respondent is emancipated, born in Catalonia, and the level of education of their parents (Egan, 2012).

Besides, the research design includes a variable indicating the survey context in order to capture time changes not explained by other variables in both models. This methodology corrects differences in the population statistical distribution of the variables of interest of ideology and sexual orientation. Additionally, we control for the size of the town of residence of respondents as urbanization has been demonstrated to be linked to the expansion of LGBTIQ + rights and the presence of LGBTIQ + organizations (Ayoub & Kollman, 2021), which would foster coming out processes.

Results & Discussion

Descriptive Statistics

Catalan Generation Z individuals are less heterosexual than their Millennial counterparts regardless of gender (Fig. 1). However, generational trends differ between men and women. Among men, heterosexual identity remains relatively stable across Generation Z (90.0%) and Millennials (92.2%) - a minimal decrease of around 2% across cohorts. Still, descriptive statistics reveal an inversion within the internal composition of non-heterosexuality across generations. While around 46.15% of Catalan, non-heterosexual Millennial men identify as bisexual, questioning or other sexual identities, this share approaches two-thirds of their Generation Z counterparts (64%). On the contrary, the share of individuals identifying as exclusively homosexual drops by 15%, while Questioning men double their previous share (1.8%) and Other categories remain the same (> 1%).

Regardless of generations, Catalan young women are overall less heterosexual and exhibit a more pronounced tendency to identify with fluid identifications (i.e. bisexuality) in comparison to men. In this latter category, there is a marked shift towards non-heterosexuality from Millennials (10.5%) to Generation Z (21.3%). This trend is largely driven by two drivers. First, the consolidation of bisexuality as the main non-heterosexual self-identification label. Second, the expansion of Questioning and Other categories at the expense of exclusive homosexuality and heterosexuality binary categories. Altogether, they both provide critical empirical evidence of the substantial shift in sexual identification, and its asymmetric socialization depending on gender and generation.

The gender asymmetry in (publicly) coming-out rates reveal an extraordinary continuity within the masculine cohort of Millennials. If we compare interviewed Millennials in the Catalan Youth Survey of 2017 versus its 2022 version, sexual categories’ distribution is virtually identical among men if we take into account the margins of error (Fig. 2). On the other hand, Millennial women have evolved in their understanding of sexuality over time. All LGB + categories present increases, but the most relevant ones come again from the expansion of bisexuality, questioning and other categories that defy the rigid straitjacket of the cisheteronormative binary. In conclusion, there is no interblock movement within men regarding sexual identity, whereas it is amply noticeable amongst women.

The evolution of Catalan Gen Z respondents both buttresses and unsettles these previous findings (Fig. 3). Unlike Millennial men, Gen Z males slightly open up to alternatives to heterosexuality more aligned with bisexuality. In Gen Z women, there is a radical shift in the short period of five years with heterosexual identification dropping 15% in the five years between the surveys. Again, the trend buttresses sexual fluidity trends. Overall, Catalan Gen Z respondents are more open to sexual fluidity, but this trend is markedly stronger among women with more than 25% of them identifying as LGB+.

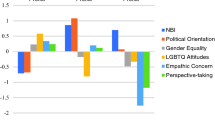

Heterosexual men appear as the least liberal/socially liberal group (66.0%) alongside bisexual men (76.7%) and heterosexual women (78.3%) (Fig. 4). Altogether, sexual minorities are the more leftist constituencies within their same gender. However, a cross-gender analysis reveals that gay and bisexual men are to the right of their female counterparts. As in Canada (Guntermann & Beauvais, 2022), bisexual women appear as the most socially liberal group followed by lesbians. Altogether, an intersectional analysis of gender and sexual orientation reveals that heterosexual men (17.5%) and bisexual men (15.1%) are the most rightist groups followed by heterosexual women (10.9%), gay men (9.9%), lesbians (5.7%), and bisexual women (3.5%). Figure 5 provides further information with the original seven-category ideology variable.

Ideology functions differently across men and women to predict sexual orientation (Fig. 6). While sexual orientation is present across all ideologies, gay and bisexual young men are disproportionately more likely to identify as Left albeit they are also present among Centrists and Conservatives. On the contrary, the lion’s share of bisexual and lesbian women identify as Left, with the share of sexual minorities clearly diminished among centrist and rightist women. This trend replicates itself if we analyze the descriptives with the original ideology variable (Fig. 7). In consonance with the rigidity-of-the-right theory (Adorno et al., 1950; Jost, 2021) and the ideological extremes theory (Greenberg & Jonas, 2003), we find that ideology significantly correlates with sexual identity.

However, the strength and mechanisms of the relationship are asymmetric across gender. On the one hand, men exhibit a mix of the rigidity-of-the-right theory and the ideological extremes theory, but heterosexuality remains hegemonic across ideologies. More extreme left and right-wing ideologies are associated with higher chances of male bisexuality (rigidity-of-the-right theory), whereas non-extreme leftist and rightist views are mostly, but not exclusively associated with gay identity (mix of rigidity-of-the-right theory and the ideological extremes theory). On the other hand, women as a whole are characterized by the rigidity-of-the-right theory - identifying as Far-Left or Left greatly diminishes heterosexuality identification. This trend is particularly strong for bisexual women, who make up almost one third of Far-Left women and 15% of Leftist women, respectively (rigidity-of-the-right theory). Conversely, more extreme left and right-wing ideologies are associated with higher chances of lesbian identity (ideological extremes theory).

Regression Analyses

Sexual Orientation as Predictor of Ideology

Our first model examines the explanatory power of sexual orientation to affect the ideology of Millennials and Generation Z individuals. Table 1 provides interesting insights on the factors that influence Catalan youth to identify with the Center and the Right versus the Left, including the interaction between sexual orientation and gender. The base category against which other groups compare is heterosexual men who identify as leftist. To start, bisexual women (p-value < 0.001), lesbians (p-value < 0.05) and gays (p-value < 0.01) are strongly to the left of heterosexuals, including heterosexual women (p-value < 0.001). In this case, lesbian women are slightly to the left of gay men, but to the right of bisexual women. These findings suggest that the gender asymmetry is bigger among bisexuals than gays and lesbians. Whereas bisexual women are less likely to identify as right-wing versus straight heterosexual men (p-value < 0.001), bisexual men are as likely as their heterosexual counterparts to identify as right-wing politically.

Our results reveal that bisexual women and gay men are the most leftist groups within their corresponding sex-gender. However, differences between bisexuals and homosexuals are more conspicuous among women than men. To put it in other words, bisexuality is the sexual orientation that drives individuals more to the left, but this trend is markedly stronger among bisexual women than not men. Besides, we find no difference in ideological positioning between Generation Z and Millennials. All control variables go in the expected theoretical direction.

In summary, women are generally more leftist than men across all sexual orientations, with minimal differences among heterosexual women and men. In line with previous literature in the United States (Egan, 2012; Hertzog, 1996; Schaffner & Senic, 2006) and Europe (Turnbull-Dugarte, 2020), our results show that sexual minorities are more socially liberal than their heterosexual counterparts. However, our findings also demonstrate that monolithic understandings of gender and/or sexuality preclude us from fully understanding the big picture of ideology, sexual orientation and gender, thus vindicating Swank’s (2018a) concept of “gendered sexualities”. Additionally, our results go in the same direction as previous studies in Canada claiming that bisexual women are the most leftist group, and that differences between heterosexual men and women are not that significant (Guntermann & Beauvais, 2022).

Ideology as Predictor of Sexual Orientation

Our second model examines the explanatory power of generation, gender and ideology to predict the sexual orientation of Millennials and Generation Z individuals. Table 2 provides interesting insights on the factors that influence Catalan youth to identify with different sexualities, including the interaction between gender and ideology. Figures 8, 9 and 10 offer graphical evidence of the predicted probabilities of identification with heterosexuality, bisexuality and homosexuality across ideology (Left, Center and Right). The base category against which other groups compare is heterosexual men who identify as leftist.

Centrist and rightist individuals are 0.301 and 0.234 times more likely to identify as gay and lesbian in comparison to leftist individuals (p-value < 0.05) holding all the other variables constant, respectively. In turn, both Millennial and Gen Z women are less likely than Millennial men to identify as homosexual (p-value < 0.05), but much more likely to self-label themselves as bisexuals in comparison to their male counterparts (p-value < 0.001). Our results further uncover that right-wing Gen Z women are much less likely than leftist Millennial men to identify as bisexual (p-value < 0.01), a trend which finds similar evidence for Gen Z rightist men.

Further, Table 3; Fig. 11show that results hold even if the independent and dependent variables are operationalized slightly differently. On the one hand, Conservative ideology (Center-right to Far-right) versus others defines ideological differences, and a binary variable differentiating bisexual, questioning and other sexual identities from the rest (excluding NA/DK) defines sexual fluidity. Catalan young women and Gen Z men are more likely than Millennial men to be sexually fluid, but this trend is particularly pronounced among Gen Z women.

Leftist ideology is a critical predictor to identify as bisexual, Questioning and Other. Nonetheless, leftist ideology has the strongest effects in questioning the sexual binary among Generation Z women and men. Critically, our findings highlight the significance of generational differences in identifying as bisexual or fluid. Additionally, we find no statistically significant increase in the rate of homosexuals across generations, thus further vindicating our claim. This is cogent with previous literature that find Generation Z as the “fluent generation” and Millennials as the “proud generation” (Bitterman & Hess, 2021; Coleman-Fountain, 2014; Dhoest, 2022; Hammack et al., 2018; Katz-Wise, 2015; Russell et al., 2009). Overall, all hypotheses find reasonable total or partial evidence across descriptive and regression techniques (Table 4).

Conclusions

In this article, we have employed an intersectional analytical perspective to investigate whether ideology moderates coming out as sexual minority among Catalan Gen Z and Millennials, and the moderating roles of gender and generation in this relationship. Drawing on Political Science and Social Psychology accounts, our argument defended that younger women on the Left should be more likely to identify as sexual minorities due to their awareness of the intersecting oppressions of patriarchy and heteronormativity. In the same fashion, we expected younger men on the Right should be the least likely to identify as sexual minorities due to the relative continuity of hegemonic masculinity (Connell, 2005) within these interlocking systems of oppression. Overall, our descriptive and inferential statistics findings have provided ample evidence of the moderating role of generation and gender to account for the role of ideology to orient self-labeling as sexual minorities and sexual fluidity in the first large-N study in Southern Europe.

In line with the Anglo-Saxon literature, our results speak about the increase of fluidity in sexual orientation among younger generations. Compared to Millennials, Generation Z individuals in Catalonia demonstrate greater sexual fluidity, but only in non-exclusive sexual identifications (i.e., bisexuality). On the contrary, identification with exclusive, non-heterosexual sexualities (i.e., gay and lesbians) appears to have decreased across generations, even when broken by (binary) operationalizations of (sex-)gender between men and women. These findings corroborate and expand the external validity of previous studies in the UK (Coleman-Fountain, 2014), Australia (Grant & Nash, 2020) and Flanders, Belgium (Dhoest, 2022) with multilevel evidence from Catalonia. The case of Catalonia is conspicuously useful to test our proposition given that (1) attitudes, social norms and legislation regarding same-sex sexualities and individuals have experienced a long-standing evolution in comparison to other European countries, and (2) conflict around same-sex sexualities have been channeled through clear ideological and partisan lines.

Critically, this study has introduced political ideology as a predictor of sexual orientation, thus recognizing the bidirectional relationship between the variables. As with previous studies in the United States, we have found that more socially liberal individuals identify as LGB + in comparison to center and right ideologies due to ideologies being at least partly a product of personality and psychological traits (Carney et al., 2008; Jost, 2021). However, differences across ideologies can only be understood considering gender and generations. Overall, we find that Catalan young women tend to bring “their identities into alignment with their politics’’ (Egan, 2020, p. 699) to a higher degree than men. This is consistent with the stronger role of socialization among women to self-label as sexual minorities (Diamond, 2008) as well as the asymmetric changes in gender ideology between men and women (Massey et al., 2021), with young women increasingly questioning heteropatriarchal relations than young men. In this sense, these results also have an impact on the theorization of the causes of the shifting patterns of sexual identification among generations, which has been focused on pointing at neoliberalism as one of the main causes (Duggan, 2012). While it may influence young people’s sexual identification, this shift shouldn’t be only seen because of the assimilation and individualization of sexual politics, but also identified as young people’s agentic move derived from feminist politics.

To conclude, the findings urge to introduce sexuality and gender identity in the study of political behavior. From a (binary) gender gap (Albaugh et al., 2023) perspective, young women are consistently more progressive than their male counterparts regardless of context or other individual characteristics (van Ditmars, 2023; Donovan, 2023). Still, sexuality and gender identity are missing to explain a big part of the variation as suggested by the findings of this article. Further quantitative research about sexual identification among youth and the overall population would benefit from longitudinal data to test whether the impact of ideology on predicting sexual orientation varies over individuals’ lifespans (Diamond, 2008). In this vein, studies should ask for a variety of questions that capture different dimensions of sexuality apart from identification, such as the gender of the partner (if any) and reported same-sex behavior (Ramírez Dueñas, 2022b). Sexual orientation identification should be asked both in closed categories and a continuum to explore the complex picture of sexual fluidity across societies and within individuals. Finally, studies in Europe should include the ethnicity/race of respondents to assess whether there are significant differences, as in Anglo-Saxon contexts, between Whites and racialized Others.

Data Availability

The data is available upon request to the authors.

References

Abou-Chadi, T., & Finnigan, R. (2019). Rights for same-sex couples and public attitudes toward gays and lesbians in Europe. Comparative Political Studies, 52(6), 868–895.

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., & Sanford, R. N. (1950). The authoritarian personality. Harper.

Albaugh, Q., et al. (2023). From gender gap to gender gaps: Bringing Nonbinary people into Political Behavior Research. APSA Preprints. https://doi.org/10.33774/apsa-2023-5bh8v.

Allen, M. S., & Robson, D. A. (2020). Personality and sexual orientation: New data and meta-analysis. The Journal of Sex Research, 57(8), 953–965.

Ayoub, P. M., & Garretson, J. (2017). Getting the message out: Media context and global changes in attitudes toward homosexuality. Comparative Political Studies, 50(8), 1055–1085.

Ayoub, P. M., & Kollman, K. (2021). Same)-sex in the city: Urbanisation and LGBT + I rights expansion. European Journal of Political Research, 60(3), 603–624.

Bailey, J. M. (2009). What is sexual orientation and do women have one? Contemporary perspectives on lesbian, gay, and bisexual identities, 43–63.

Barber, M., & Pope, J. C. (2019). Does party trump ideology? Disentangling party and ideology in America. American Political Science Review, 113(1), 38–54.

Bishop, M. D., Fish, J. N., Hammack, P. L., & Russell, S. T. (2020). Sexual identity development milestones in three generations of sexual minority people: A national probability sample. Developmental Psychology, 56(11), 2177.

Bitterman, A., & Hess, D. B. (2021). Understanding generation gaps in LGBT + Q + communities: Perspectives about gay neighborhoods among heteronormative and homonormative generational cohorts. The life and Afterlife of gay Neighborhoods: Renaissance and Resurgence, 307–338.

Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge.

Butler, J. (2001). What is critique? Transversal Texts. https://transversal.at/transversal/0806/butler/en

Callis, A. S. (2014). Bisexual, pansexual, queer: Non-binary identities and the sexual borderlands. Sexualities, 17(1–2), 63–80.

Calvo, K. (2017). ¿Revolución o reforma? La transformación de la identidad política del movimiento LGTB en España, 1970–2005. Madrid. Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Carney, D. R., Jost, J. T., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2008). The secret lives of liberals and conservatives: Personality profiles, interaction styles, and the things they leave behind. Political Psychology, 29(6), 807–840.

Coffe, H., Fraile, M., Alexander, A., Fortin-Rittberger, J., & Banducci, S. (2023). Masculinity, sexism and populist radical right support. Frontiers in Political Science, 5, 1038659.

Coleman-Fountain, E. (2014). Lesbian and gay youth and the question of labels. Sexualities, 17(7), 802–817.

Connell, R. W. (2005). Masculinities (2nd ed.). University of California Press.

Dhoest, A. (2022). Generations and shifting sexual identifications among flemish non-straight men. Journal of Homosexuality, 1–24.

Diamond, L. M. (2008). Sexual fluidity: Understanding women’s love and desire. Harvard University Press.

Diamond, L. M. (2014). Gender and same-sex sexuality. In D. L. Tolman, L. M. Diamond, J. A. Bauermeister, W. H. George, J. G. Pfaus, & L. M. Ward (Eds.), APA handbook of sexuality and psychology, Vol. 1. Person-based approaches (pp. 629–652). American Psychological Association.

Diamond, L. M. (2016). Sexual fluidity in male and females. Current Sexual Health Reports, 8, 249–256.

Diamond, L. M. (2021). The new genetic evidence on same-gender sexuality: Implications for sexual fluidity and multiple forms of sexual diversity. The Journal of Sex Research, 58(7), 818–837.

Diamond, L. M., Dickenson, J. A., & Blair, K. L. (2017). Stability of sexual attractions across different timescales: The roles of bisexuality and gender. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 193–204.

Donovan, T. (2023). Measuring and predicting the radical-right gender gap. West European Politics, 46(1), 255–264.

Duggan, L. (2012). The Twilight of Equality: Neoliberalism, Cultural politics and the attack on democracy. Beacon Press.

Egan, P. J. (2008). Explaining the distinctiveness of lesbians, gays, and bisexuals in American politics. Gays, and Bisexuals in American Politics (March 2008) SSRNhttps://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1006223

Egan, P. J. (2012). Group cohesion without group mobilization: The case of lesbians, gays and bisexuals. British Journal of Political Science, 42(3), 597–616.

Egan, P. J. (2020). Identity as dependent variable: How americans shift their identities to align with their politics. American Journal of Political Science, 64(3), 699–716.

Friedman, C. K., & Ayres, M. (2013). Predictors of feminist activism among sexual-minority and heterosexual college women. Journal of Homosexuality, 60(12), 1726–1744.

Ghaziani, A. (2011). Post-gay collective identity construction. Social Problems, 58(1), 99–125.

Grant, R., & Nash, M. (2020). Homonormativity or queer disidentification? Rural Australian bisexual women’s identity politics. Sexualities, 23(4), 592–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460719839921.

Greenberg, J., & Jonas, E. (2003). Psychological motives and political orientation–the left, the right, and the rigid: Comment on Jost et al. (2003). Psychological Bulletin, 129(3), 376–382.

Grollman, E. A. (2017). Sexual orientation differences in attitudes about sexuality, race and gender. Social Science Research, 61, 121–141.

Guntermann, E., & Beauvais, E. (2022). The Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Vote in a more tolerant Canada. Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de Science Politique, 55(2), 373–403.

Haltom, T. M., & Ratcliff, S. (2021). Effects of sex, race, and education on the timing of coming out among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the US. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50, 1107–1120.

Hammack, P. L., Frost, D. M., Meyer, I. H., & Pletta, D. R. (2018). Gay men’s health and identity: Social change and the life course. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47, 59–74.

Hertzog, M. (1996). The lavender vote: Lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals in American electoral politics. NYU.

Hunklinger, M., & Kleer, P. (2024). Why do LGB + vote left? Insight into left-wing voting of lesbian, gay and bisexual citizens in Austria. Electoral Studies, 87, 102727.

IPSOS (2023). LGBTIQ + Pride 2023 – A 30-Country Ipsos Global Advisory Survey URL: https://www.ipsos.com/en/pride-month-2023-9-of-adults-identify-as-lgbt.

Jost, J. T. (2021). Left and right: The psychological significance of a political distinction. Oxford University Press.

Katz-Wise, S. L. (2015). Sexual fluidity in young adult women and men: Associations with sexual orientation and sexual identity development. Psychology & Sexuality, 6(2), 189–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2013.876445. https://doi-org.sare.upf.edu/.

Kaufman, M. (2019). The time has come: Why men must join the gender equality revolution. Counterpoint.

Kimmel, M. (2013). Angry white men: American masculinity at the end of an era. Nation Books/Perseus.

León, M., Alvariño, M., & Soler-Buades, L. (2022). Explaining morality policy coalitions in Spanish parliamentary votes: The interaction of the church-state conflict and territorial politics. South European Society and Politics, 27(2), 197–222.

Mannheim, K. (1952). The sociological problem of generations. Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge, 306, 163–195.

Marshall, D., Aggleton, P., Cover, R., Rasmussen, M. L., & Hegarty, B. (2019). Queer generations: Theorizing a concept. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 22(4), 558–576.

Mason, L. (2016). A cross-cutting calm: How social sorting drives affective polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(S1), 351–377.

Mason, L. (2018). Uncivil agreement: How politics became our identity. University of Chicago Press.

Massey, S. G., Mattson, R. E., Chen, M. H., Hardesty, M., Merriwether, A., Young, S. R., & Parker, M. M. (2021). Trending queer: Emerging adults and the growing resistance to compulsory heterosexuality. Sexuality in Emerging Adulthood, 181–196.

Michelson, M. (2019). The power of visibility: Advances in LGBT + rights in the United States and Europe. The Journal of Politics, 81(1), 1–5.

Morgenroth, T., Kirby, T. A., Cuthbert, M. J., Evje, J., & Anderson, A. E. (2022). Bisexual erasure: Perceived attraction patterns of bisexual women and men. European Journal of Social Psychology, 52(2), 249–259.

Moskowitz, D. A., Rendina, H. J., Avila, A., A., & Mustanski, B. (2022). Demographic and social factors impacting coming out as a sexual minority among Generation-Z teenage boys. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 9(2), 179.

Page, D., & Paulin, T. (2022). Revisiting the lavender vote. Electoral Studies, 80, 102543.

Ramírez Dueñas, J. M. (2022a). Devolviendo La Visibilidad a Los invisibles. Preguntando La orientación sexual en las encuestas de opinión pública en España. Estudios LGBTIQ + Comunicación Y Cultura, 2(1), 117–128.

Ramírez Dueñas, J. M. (2022b). El factor explicativo de la orientación sexual en El comportamiento político y electoral en España (2016–2021). RES Revista Española De Sociología, 31(4).

Ramírez Dueñas, J. M., Cordero, G., & Turnbull-Dugarte, S. J. (2023). Actitudes y voto de la juventud LGBA + en España. Federación Estatal de Lesbianas, Gais, Trans, Bisexuales, Intersexuales y más URL: https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/484106/1/informe_vISBN.pdf.

Russell, S. T., Clarke, T. J., & Clary, J. (2009). Are teens ‘post-gay’? Contemporary adolescents’ sexual identity labels. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(7), 884–890.

Schaffner, B., & Senic, N. (2006). Rights or benefits? Explaining the sexual identity gap in American political behavior. Political Research Quarterly, 59(1), 123–132.

Schnabel, L. (2018). Sexual orientation and social attitudes. Socius, 4, 2378023118769550.

Serracant, P. (2018). Enquesta a la joventut de Catalunya 2017: Volum 1 i 2 Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament de Drets Socials. Retrieved from https://dretssocials.gencat.cat.

Swank, E. (2018a). Who voted for Hillary Clinton? Sexual identities, gender, and family influences. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 14(1–2), 21–42.

Swank, E. (2018b). Sexual identities and participation in liberal and conservative social movements. Social Science Research, 74, 176–186.

Tankard, M. E., & Paluck, E. L. (2017). The effect of a Supreme Court decision regarding gay marriage on social norms and personal attitudes. Psychological Science, 28(9), 1334–1344.

Turnbull-Dugarte, S. J. (2021). Multidimensional issue preferences of the European lavender vote. Journal of European Public Policy, 28(11), 1827–1848.

Vaccaro, A. (2009). Intergenerational perceptions, similarities and differences: A comparative analysis of lesbian, gay, and bisexual millennial youth with generation X and baby boomers. Journal of LGBT + Youth, 6(2–3), 113–134.

Van Ditmars, M. M. (2023). Political socialization, political gender gaps and the intergenerational transmission of left-right ideology. European Journal of Political Research, 62(1), 3–24.

Verd, J. M., Julià, A., & Valls, F. (2022). Enquesta a la joventut de Catalunya 2022: Volum 1, 2, i 3 Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament de Drets Socials. Retrieved from https://dretssocials.gencat.cat.

Wurthmann, L. C. (2023). German gays go green? Voting behaviour of lesbians, gays, and bisexuals in the 2021 German federal election. Electoral Studies, 81, 10558.

Yeung, E. S., & Quek, K. (2024). Self-reported political ideology. Political Science Research and Methods, 1–22.

Funding

This work was supported by PID2020-118661RA-I00 (Spanish Investigation Agency, Agencia Estatal de Investigación) and MCIN/AEI/ https://doi.org/10.13039/501100011033 (Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and development. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Joel Cantó Roche. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cantó, J., Rodó-Zárate, M. Gender-Ideology Trouble? Ideology, Gender, and Generation as Factors in LGB+ Self-identification among Gen Z and Millennials in Catalonia. Sexuality & Culture (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-024-10252-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-024-10252-w