Abstract

Recent evidence suggests that young sexual minority men’s sexual position identities (e.g., “top,” “bottom,” “versatile”) may be governed by dynamic influences. Yet, no study has prospectively examined whether, how, and why this aspect of sexual minority men’s sexuality changes over time. Consequently, the present study investigated the extent to which young sexual minority men use sexual position identities consistently over time, typical patterns of position identity change, explanations given for this change, and the correspondence of changing sexual position identities with changing sexual behavior and fantasies. A total of 93 young sexual minority men indicated their sexual position identity, behavior, and fantasies at two assessment points separated by 2 years. Following the second assessment, a subset (n = 28) of participants who represented the various sexual position identity change patterns provided explanations for their change. More than half (n = 48) of participants changed their sexual position identity. Participants showed a significant move away from not using sexual position identities toward using them and a significant move toward using “mostly top.” Changes in position identity were reflected, although imperfectly, in changes in sexual behavior and largely not reflected in fantasy changes. Participants offered 11 classes of explanations for their identity changes referencing personal development, practical reasons, changing relationships, and sociocultural influences. Previous investigations of sexual minority men’s sexual position identities have not adequately attended to the possibility of the changing use of the sexual position categories “top,” “bottom,” and “versatile” across young adulthood. Results of the present study suggest the possibility of a more fluid, context-dependent use of these terms than previously documented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

While longitudinal research on sexual minority women’s sexuality has revealed fluidity over time in same-sex and other-sex partner attractions and associated identities (e.g., “bisexual,” “lesbian”) (Diamond, 2008), parallel longitudinal investigations of sexual minority men’s erotic attractions and identities are largely non-existent. This discrepancy likely reflects previous findings that men’s sexual attractions are more fixed to one gender and thus less likely to change over time and context (Baumeister, 2000; Chivers, Rieger, Latty, & Bailey, 2004; Diamond, 2003; Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994; Peplau, 2003; Savin-Williams, Joyner, & Rieger, 2012). However, partner gender represents only one organizer of sexual orientation (Stein, 1999). A growing body of research suggests that many sexual minority men show attraction and form identities based on the position that they and their partners assume during sexual intercourse (e.g., “top,” “bottom,” “versatile”) (Wegesin & Meyer-Bahlburg, 2000). While these sexual positioning behaviors, attractions, and identities have clear relevance to contemporary sexual minority men’s lives (Hoppe, 2011; Kippax & Smith, 2001), no study to date has prospectively examined whether, how, and why these aspects of sexual minority men’s sexuality change over time. Further, no study has examined these potentially fluid phenomena specifically among sexual minority men in young adulthood, a propitious developmental stage during which to examine questions of sexual identity formation and growth (Cohler & Hammack, 2007; Kroger, Martinussen, & Marcia, 2010; Plummer, 1995).

Early sociological and psychological research into sexual minority male romantic and sexual relationships (Harry & DeVall, 1978; Hooker, 1965; Saghir & Robins, 1973; Silverstein, 1981) sought to dispel as overly simplistic, although historically accurate (e.g., Chauncey, 1994), notions of “butch/femme” or “trade/fairy,” essentially male/female, role dichotomies in sexual pairings between men (Bieber et al., 1962; Haist & Hewitt, 1974; Tripp, 1975). Yet, many contemporary sexual minority men continue to organize their sexuality using the categories “top,” “bottom,” and “versatile.” Such categories not only describe a preference for insertive, receptive, or both types of positions during anal sex, but also enable sexual minority men to engage discourses of power and pleasure during sex (e.g., Hart, Wolitski, Purcell, Gòmez, & Halkitis, 2003; Hoppe, 2011; Kippax & Smith, 2001; Moskowitz & Hart, 2011; Wegesin & Meyer-Bahlburg, 2000). Recognizing this fact, recent studies have asked sexual minority men to choose among these descriptive identity categories so that associations between these categories and sexual minority men’s experience of sex, HIV risk, and psychological and physical traits can be established.

Results of these studies have advanced conceptual understandings of the ways in which sexual position categories engender power and pleasure during sex between men (Hoppe, 2011; Kippax & Smith, 2001). Other studies have furthered understanding of behavioral HIV risk profiles, with men who identify as “bottom” being about twice as likely to acquire HIV than men who identity as “top” (Wegesin & Meyer-Bahlburg, 2000; Wei & Raymond, 2011). Other work has established that men with relatively lower levels of educational attainment, men born in Asia living in the U.S., men with smaller penises, and men who report more feminine interests and activities as children and adults are more likely to prefer being receptive during intercourse or to identify as “bottom” (Grov, Parsons, & Bimbi, 2010; Wei & Raymond, 2011; Weinrich et al., 1992). Conversely, this work has shown that men who report being more masculine and having larger penises are more likely to prefer being insertive during intercourse or to identify as “top” (Grov et al., 2010; Hart et al., 2003). Further, in China, a country with relatively rigid gender roles and less support for homosexuality compared to the U.S., gay men who identify as “bottom” report more expressiveness than “tops,” who in turn report more masculine interests and more instrumentality than “bottoms” (Zheng, Hart, & Zheng, 2012).

Although researchers continue to examine sexual position identities (e.g., “top,” “bottom,” “versatile”) and preferences (e.g., for insertive versus receptive sex), there is relatively little understanding of the extent to which these identities and preferences represent universal concepts that generalize across contexts. With very few exceptions (e.g., Wegesin & Meyer-Bahlburg, 2000), researchers have conceptualized the terms “top,” “bottom,” and “versatile” as reflecting an invariant system of sexual categorization. Although this conceptualization may accurately reflect sexual minority men’s own understanding of these terms, it likely obscures any fluid or context-dependent use of them. Only one study to date has examined change in sexual minority men’s position identities, finding stability in these identities alongside a significant general reduction in their use over a 5-year period (Wegesin & Meyer-Bahlburg, 2000). However, this study relied solely on retrospective reports of position identities and did not attend to age cohort, two common drawbacks in developmental research on sexual minority individuals’ sexuality (Boxer & Cohler, 1989).

In addition to providing an opportunity to capture context-dependent fluctuations in position identities, a prospective design would allow for testing whether changes in position identity correspond to changes in position fantasies and position behavior. While the categories “top,” “bottom,” and “versatile” consistently have been shown to predict sexual minority men’s actual sexual behavior (Moskowitz, Rieger, & Roloff, 2008; Wegesin & Meyer-Bahlburg, 2000), some sexual minority men report a discrepancy between their actual and ideal position (Moskowitz & Hart, 2011). By examining concordance between position identities, fantasies, and behaviors prospectively, the present study more reliably captures synchrony or discrepancy among these three primary, yet distinct (Laumann et al., 1994; Savin-Williams, 2006), components of sexuality over time and can help clarify the behavioral and cognitive-affective correlates of position identity. Studies examining other forms of sexuality (e.g., partner gender) as a function of identity, behavior, and attraction have, in fact, found a significant lack of overlap across these components (Laumann et al., 1994). While these three aspects of sexual position have not yet been examined in young sexual minority men, strong evidence suggests that young sexual minority men’s sexuality may follow a standard developmental sequence, with sexual identity and behavior eventually aligning with sexual fantasies (McClintock & Herdt, 1996). Employing a prospective design with young sexual minority men offers an opportunity to capture sexual minority men’s position identities, behaviors, and fantasies at a developmental stage marked by sexual identity formation and growth (Cohler & Hammack, 2007; Plummer, 1995).

Present Study

In order to predict specific patterns of sexual position identity change, explanations for this change, and overlap with changes in behaviors and fantasies, we draw on diverse theoretical perspectives, both psychosocial and sociocultural, which offer competing hypotheses.

Idiographic, psychosocial factors, such as personality, race, and body traits, might determine stability or change in sexual position. While these factors are relatively stable within an individual, their influence on position identity may vary across developmental, relational, and situational contexts. Other, less stable psychosocial factors may also explain patterns of position identity change. Internalized homophobia, for example, is associated with identifying as a “top” (Hart et al., 2003), and while no research has examined absolute changes in young sexual minority men’s internalized homophobia over time, it is possible that as an individual’s internalized homophobia decreases, so too would his likelihood of identifying as a “top.”

In addition to psychosocial factors, sociocultural factors may also explain certain patterns of position identity change. For instance, standing outside society’s expectation of heterosexuality and increasingly being accepted despite doing so (Cohler & Hammack, 2007), young sexual minority men in contemporary U.S. society are strongly positioned to transgress other cultural expectations, such as polar enactments of gender and power in sexual relationships. As a result, a large proportion of young sexual minority men in this study may see sexual position identities as unduly constraining constructs borrowed from ill-fitting models of gender and either not use them at all or adopt them flexibly across contexts. If this conceptualization is true, a large proportion of participants would indicate not using position identities and those who do use them would show a high degree of position identity change over time citing numerous explanations for their change that extend beyond the traditional notions of gender and power invoked in early works on sexual position identity (e.g., Bieber et al., 1962).

Other accounts, however, suggest that despite a history of subverting traditional notions of gender for many decades, the gay male community today fully upholds hegemonic displays of gender (Kimmel, 1996; Taywaditep, 2001). These displays are potentially most obvious in sexual minority men’s anti-effeminacy attitudes, which are often invoked in the search for potential romantic and sexual partners using normative forms of “straight-acting,” “masculine” attractiveness embedded in online and physical gay communities (Bailey, Kim, Hills, & Linsenmeier, 1997; Bartholome, Tewksbury, & Bruzzone, 2000; Jeffries, 2009; Taywaditep, 2001). Drawing on this particular framework, we might expect participants to use position identities consistently over time with those who change position identities changing toward “top” as a result of increasing exposure to gay community norms of masculinity and the association between masculinity and being a “top” (Grov et al., 2010). This pattern would parallel a general trend toward defeminizing behaviors and attitudes that has been noted across sexual minority men’s young adulthoods (Taywaditep, 2001).

Finally, given that previous studies of sexual minority men’s sexual positioning fail to articulate whether the phenomenon under investigation is sexual behavior, identity, attraction, or a combination thereof, we could not conclusively hypothesize the extent of overlap among these factors expected in the present study. However, given the high degree of discordance among behavior, identity, and attraction in other components of men’s sexuality (e.g., partner gender) (Laumann et al., 1994), it is at least possible that such discordance exists for sexual positioning as well.

In sum, we sought to investigate: (1) the number of participants who changed sexual position identities across 2 years, (2) the extent to which sexual position identities changed, (3) characteristic patterns of sexual position identity change over time, (4) explanations given for sexual position identity change, and (5) the correspondence of changes in sexual position identity with changes in sexual position behavior and fantasies.

Method

Participants

Sexual minority men (n = 128) between the ages of 18 and 25 years who were enrolled as full-time students at large public and private universities participated as part of a larger study on young sexual minority men’s health. We used publicly available data to determine the largest colleges and universities by full-time undergraduate enrollment (U.S. Department of Education, 2010). Forty-five of these universities listed publicly available and active email accounts for their lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) student group. Participants responded to an email sent to the listservs of LGBT student groups on those campuses advertising the study as an examination of the experiences of college-aged sexual minority men. After providing consent for this IRB-approved study, participants indicated their sexual orientation, age, and college student status to ensure that included participants identified as sexual minority men and were college students younger than age 26. Sexual orientation was assessed with the item “What best describes your identity?” choosing from the following response options: (1) gay, (2) heterosexual, (3) bisexual, but mostly gay, (4) bisexual (equally gay and heterosexual), (5) bisexual, but mostly heterosexual, (6) queer, (7) uncertain, don’t know for sure. Participants were retained in this study if they indicated being “gay” (n = 106), “bisexual, but mostly gay” (n = 16), “bisexual, equally gay and heterosexual” (n = 1), and “queer” (n = 5). Participants lived across the U.S.: West (n = 13, 14.0 %), Midwest (n = 28, 30.1 %), Northeast (n = 25, 26.9 %), South (n = 22, 23.7 %). Five (5.3 %) participants indicated currently living outside of the U.S. or did not provide a response to this item.

Thirty-five (27.3 %) participants could not be reached for Time 2 assessments, leaving 93 participants for the final analyses. Non-completers did not differ from completers on Time 1 age, race/ethnicity, or relationship status. Participants’ mean age at Time 1 was 20.61 years (SD = 1.75). The distribution of participants’ race/ethnicity was: Black/African American (n = 5, 5.4 %), White/Caucasian (n = 64, 68.8 %), Latino/Hispanic (n = 8, 8.6 %), Asian (n = 8, 8.6 %), Native American (n = 2, 2.2 %), Pacific Islander (n = 1, 1.1 %), Caribbean (n = 1, 1.1 %), mixed race (n = 2, 2.2 %); 2 (2.2 %) participants did not indicate a race/ethnicity. Fewer than half (n = 39, 41.9 %) were in a relationship at the start of the study.

Procedure

Participants submitted data regarding demographics and position identity, behavior, and fantasies at two time points separated by 2 years. To determine explanations for position identity change, within 8 weeks of receiving Time 2 data, we interviewed 28 participants who had changed their sexual self-label from Time 1 to Time 2 in an approximately 20-min phone interview consisting of five questions. These 28 participants were randomly chosen to represent all 20 categories of position identity change reported by participants over the 2 years (e.g., change from “versatile” at Time 1 to “mostly bottom” at Time 2). We attempted to interview at least one participant per change category, although this was not always possible due to some participants’ lack of interest or availability for completing the qualitative follow-up.

Measures

Sexual Position Identity

Convincing empirical evidence suggests the suitability of examining components of male sexuality as dimensional constructs (Vrangalova & Savin-Williams, 2012); therefore, we assessed sexual position identity at both time points by asking participants to choose one of the following five options in response to the item stem “I identify as:” “exclusively top,” “mostly top,” “versatile,” “mostly bottom,” “exclusively bottom.” Participants could also select: “I have never labeled myself in these ways” or “I used these labels for myself in the past but not anymore.” This approach is consistent with previous assessments of sexual position identity (Grov et al., 2010).

Sexual Position Fantasies

Position fantasies at both time points were assessed by asking participants to choose “exclusively top,” “mostly top,” “versatile,” “mostly bottom,” “exclusively bottom,” or “I don’t fantasize about myself in these ways” in response to the prompt, created for this study: “In my fantasies, I am…”

Overall Anal Sex Frequency

Participants indicated the frequency with which they had anal sex in response to the prompt, created for this study: “I have anal sex:” “never,” “infrequently,” “sometimes,” and “often.”

Anal Sex Position Frequency

Participants rated the frequency with which they engaged in receptive and insertive anal intercourse in the past 30 days on a four-point Likert scale, created for this study, using the anchors “never,” “infrequently,” “sometimes,” and “often.”

Reasons for Position Identity Change

Following the completion of Time 2 measures, participants were contacted by phone by either the first or second author to provide responses to the following five questions: (1) “Two years ago, you provided the label [Time 1 identity]. This year, you provided the label [Time 2 identity]. What do those labels mean to you?” (2) “How do these labels influence your sexual life?” (3) “How do these labels influence the other areas of your life?” (4) “Our data show that some sexual minority men change their sexual self-label over time. What reasons might explain this?” (5) “What reasons might explain why your label has changed from [Time 1 identity] to [Time 2 identity]?” While the purpose of these open-ended questions was to capture participants’ reasons for changing their sexual position identities over time, we asked the first four questions to provide sufficient context for understanding the full meaning and context of identity changes as ultimately assessed more patently in the final question. Only responses that specifically referenced one’s position identity change were analyzed in this study.

Data Analysis

We utilized the full range of position identities (from “exclusively top” to “exclusively bottom”) in descriptive analyses examining the proportion of participants who changed position identities. For the sake of comparison, we also conducted these analyses collapsing across related categories (e.g., combining “exclusively top” and “mostly top” into “top”). We otherwise used the full range of position identities except in those analyses for which the large number of predictors involving all position identities would have yielded untenable power. In creating the collapsed categories, we followed the approach of Grov et al. (2010), combining “mostly top” and “exclusively top” into “top,” and “mostly bottom” and “exclusively bottom” into “bottom,” and “I don’t use the labels” or “I used these labels for myself in the past but not anymore” into “no label.” Our choice of collapsed categories was further validated through a supplementary procedure in which this study’s participants indicated their position identity on both the collapsed and dimensional scale at a separate time point, a full description of which is available from the first author. Anal sex frequency and position fantasies were treated as continuous variables in all analyses.

We conducted interviews with 28 of the 48 participants who changed their position identity in order to capture participants’ explanations of the change in their sexual position identity across the 2-year span of the study. We used the multiphase process outlined by Miles and Huberman (1994) to code these participants’ responses to the five questions listed above. Open coding was performed through numerous readings of 30 % of participants’ responses selected at random. All coders independently searched for and annotated the concepts specifically referencing participants’ position identity change, focusing on the conceptual meaning of participants’ words, sentences, and overall responses. All coders subsequently discussed their independent analyses in a series of meetings in order to arrive at a consensus of the most suitable language, or codes, for identifying and describing discrete, meaningful explanations that participants provided for their sexual position identity change. These resulting codes were then applied by two independent coders to the remaining 70 % of participants’ responses in order to determine the reliability of the coding scheme. Upon coding all discrete change explanations in the latter 70 % of narratives, the two raters evinced strong agreement (ICC = 0.83). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion until consensus was achieved. Coders identified 190 discrete sexual position identity change explanations subsumed under 11 primary codes and 20 sub-codes. Not all primary codes contained sub-codes.

Results

How Many Participants Changed Sexual Position Identities Over Time?

Table 1 summarizes the number of participants who identified with each position identity category at Time 1 and Time 2. Nearly one-third of participants at both time points identified as versatile (Time 1: n = 30, 32.3 %; Time 2: n = 29, 31.2 %). Approximately one-quarter of participants at each time point identified as “exclusively bottom” or “mostly bottom” (Time 1: n = 21, 22.6 %; Time 2: n = 25, 26.9 %). Nine (9.7 %) participants identified as “mostly top” at Time 1; more than twice as many identified as “mostly bottom” (n = 20, 21.5 %) at Time 1. The number of participants who identified as “mostly top” at Time 2 (n = 18, 19.4 %) doubled from Time 1; the number of participants who identified as “mostly bottom” stayed roughly the same at both time points (Time 1: n = 20, 21.5 %; Time 2: n = 23, 24.7 %).

Of the 93 participants who completed both assessments, 48 (51.6 %) changed their sexual position identity from Time 1 to Time 2, whereas 45 (48.4 %) indicated the same identity at both points. The number of participants who retained each of the following position identities across the 2 years was: exclusively top = 2 (2.2 %), mostly top = 3 (3.2 %), versatile = 15 (16.1 %), mostly bottom = 13 (14.0 %), exclusively bottom = 0 (0 %), I have never labeled myself in these ways = 12 (12.9 %), and I used these labels for myself in the past but not anymore = 0 (0 %). The Time 1 and Time 2 temporal patterns of position identity are reported in Table 2.

While arguments have been made for examining other components of male sexuality as dimensional constructs (Vrangalova & Savin-Williams, 2012), it could be argued that the high proportion of change reported above reflects that fact that we measured what might be a categorical construct using dimensional labels (e.g., “exclusively top,” “mostly top”). Collapsing across categories (i.e., “top,” “bottom,” “versatile,” “no label”) to assess participants’ position identity reveals that 38.7 % (n = 36) of participants changed position identity across time.

To What Degree Did Participants’ Sexual Position Identities Change Over Time?

Participants who used position identities at both time points (n = 61) changed an average of .49 (SD = .57) units in either direction on the continuous five-point scale of sexual position identity from “exclusively top” to “exclusively bottom.” Limiting this analysis to only participants who both selected position identities at both time points and changed position identities over time (n = 28) demonstrated an average change of about one unit in either direction on this continuous scale (M = 1.07, SD = .26). Of the 30 participants who indicated not using a position identity at Time 1, over half (n = 16, 53.3 %) acquired such an identity from Time 1 to Time 2. Half of these (n = 8) acquired the identity “versatile,” a proportion which was not significantly greater than chance, χ2(1, N = 93) = 3.19, p = .07.

What Patterns Were Evident in Participants’ Sexual Position Identity Changes?

Participants changed in 20 various ways. Participants were no more or less likely to leave one position identity than any other, but participants who indicated that they had used labels in the past but not currently were more likely to change from this description over the course of the 2 years than participants who indicated any other position identity, χ2(1, N = 93) = 4.95, p < .05. Participants were significantly more likely to change into “mostly top” at Time 2 than any other position identity, χ2(1, N = 93) = 8.99, p < .01, and significantly less likely to indicate not using position identity labels at Time 2 than identifying with any position category, χ2(1, N = 93) = 9.20, p < .01. Half of the participants who changed identities either changed from “versatile” (n = 12, 12.9 %) or to “versatile” (n = 17, 18.3 %). Participants who changed identities from “versatile” were significantly more likely to change identities to “mostly top” than to any other identity, χ2(1, N = 48) = 12.74, p < .001. Participants who changed to “versatile” were significantly more likely to change identities from “I have never labeled myself in these ways” than from any other identity category, χ2(1, N = 48) = 6.47, p < .05.

Why Did Participants’ Sexual Self-Labels Change Over Time?

Participants’ explanations for their sexual position identity changes referenced four broad types of reasons: personal, practical, relational, and sociocultural. All codes and sub-codes are listed in Table 3 along with the proportion of participants who indicated each.

Personal Reasons

Personal reasons included personal growth, such as concomitant changes in other aspects of identity, increased experience, increased self-awareness, increased self-confidence, and increased sexual self-awareness; greater sexual experimentation; and changes in ways of finding sexual pleasure.

The fact that nearly all of the men in the present study cited personal growth (e.g., other identity changes) or sexual development (e.g., sexual experimentation) as reasons for their position identity changes coheres with previous life course research highlighting the strong (e.g., Cohler & Hammack, 2007), yet by no means definitive (Peplau et al., 1999), influence of psychosocial factors in adolescence and young adulthood on the course of one’s sexual development. As participants came to better understand their own needs and wants, including their sexual desires, over time, they were better able to choose a position identity that represented those needs and wants. This process of sexual position identity development, as influenced by increased self-understanding over time, is captured by a participant who shifted from “mostly bottom” to “versatile” over the course of the study: “When I got more comfortable, got to know all bounds of my sexuality and myself as person, and as I matured, I came to the conclusion that I was versatile.”

For some participants, greater self-understanding of one’s sexual position paralleled an earlier process of increasing awareness of one’s sexual orientation, as with a participant who went from not using labels to identifying as “mostly top:” “I thought I was straight until high school and there was that change. There was already one big shift, which maybe makes a person more open to redefining themselves in other ways too.” For other participants, such as a young man who changed from not using labels to identifying as “mostly bottom,” sexual position identity changed with increasing experience: “When I was less experienced I wanted to bottom because I felt like I was going to be with more experienced people.” For other participants, as illustrated in the following quote from a young man who changed from “versatile” to “mostly bottom,” changes in position identity followed changes in self-confidence: “As I grow up, I can be more confident with people who are larger than me, like more athletic, and because of that I have more opportunities to bottom because before I’d hang out with people I’d be more comfortable topping because they were smaller than me.”

Practical Reasons

Practical reasons for position identity change included recognizing constraints imposed by position identities generally or by certain identities specifically, including a recognition that identifying oneself using certain categories can invoke stereotypes and that identifying as “versatile” is a way to avoid these stereotypes; issues of physical comfort, including medical issues and partners’ penis size; and reducing ambiguity in initial sexual or romantic encounters.

Participants noted that negative stereotypes, especially surrounding a “bottom” identity, constrained others’ and their own sexual freedom and partner options. One participant who went from not labeling to identifying as “mostly bottom” noted that: “The queer community has negative expectations of bottoming. I don’t really care about that so much anymore and feel comfortable with those around me identifying as a bottom. When I get the urge to have a guy inside of me, I still sometimes wonder if that will be viewed negatively.” Other participants suggested that identifying as “versatile,” can bypass preconceived correlates of “top” and “bottom” position identities. For example, a participant who moved from “mostly bottom” to “versatile” remarked: “I don’t have to be limited in who I meet now. Now that I do both, it doesn’t really matter to me. I’m looking more for the person than the position preference.”

Previous studies have found that sexual minority men’s self-reported penis size is associated with their sexual position identity (Grov et al., 2010; Moskowitz & Hart, 2011). Our results suggest that partner’s absolute and relative penis size may both influence position identity. One participant, for example, cited an expectation that partners with larger penises than his will be a “top,” but also added that the effort involved in receiving a large penis can also drive one away from identifying as a “bottom:” “Part of it has to do with the fact that it’s a physiological thing. I started off as a bottom, because my partner had a bigger penis. As I’ve become older, I’ve become a top and act as a top because it’s just so much work to be a bottom. You know, you have to relax for a while and prep your sphincter. So for me, personally, it has less to do with the cultural baggage and more the practical aspect.” To our knowledge, this is the first evidence of medical issues predicting position identity change, as they did for three of the men we interviewed, including a participant who shifted from “versatile” to “mostly top”: “I had a medical issue where I was having chronic rectal fissures and I thought ‘this isn’t worth it, I don’t have to deal with this.’ It’s healed since, but it would be me going back to the first time. I just can’t.”

Finally, eight participants, as exemplified in the following quote, noted that choosing a position identity reduces ambiguity in initial romantic and sexual encounters. “In terms of meeting new people, I think it’s easier now to figure out who’s going to take the first step, like if you meet someone online. I used to have verse on my online profile and now I have bottom.”

Relational Reasons

Nearly all of the men we interviewed gave relational explanations for changing their position identity, whether boredom, growth, communication, safety, and power within a relationship or adopting—and later relinquishing—position identities to conform to the expectations and expressed needs of one’s early relationship partners. One participant who changed from “mostly bottom” to “exclusively bottom” exemplifies the construction of sexual position identity in relation to a former partner: “I was in a relationship with someone and I was in love with that person and that was something he wanted to do because he liked it, which made it fun for me.” Similarly, a participant who changed from “versatile” to “mostly top” also noted initially relying on his initial partner’s desires to determine his own identity, while becoming more self-reliant since that relationship: “It was harder in the beginning when I just came out because I wanted badly to fit in or be a part of something even in my first relationship, feeling that I was doing something right. So I conformed to what my partner wanted or what I thought was right. I was going along with what he wanted. Now, I’m thinking more about what I want and enjoy and what I feel comfortable doing.” Another participant who was initially “versatile” described his search for elusive, but needed, nurturance through identifying as “mostly bottom:” “It has to do with being nurtured and cared for and having an adult figure that you’re going to be safe with, because I think a lot of gay people don’t have that when they come out and their families don’t nurture them. Maybe that has something to do with it—I don’t have anyone here.” Also referencing relational power, but in conjunction with STD risk, a participant who changed from “mostly top” to “versatile” noted: “I guess it has to do with vulnerability. I think our relationship dynamics are associated with that. There are safety issues that come into consideration with that. As a bottom, you are more susceptible to STDs.”

Some participants noted that adopting position identities was an efficient way to negotiate their behavior preferences with their partner. For example, a participant who initially indicated not having a position identity, but later adopting a “mostly top” identity, noted: “I think probably what happened in the meantime, is that at that time, my boyfriend and I would have been just like alternating and because that was just what we were doing, we wouldn’t have talked about it in those terms. Since then we’ve sort of figured out or decided that it’s better if he’s usually on top and I’m usually on bottom and in order to have that conversation we needed to use those terms. So that’s probably why 2 years ago it didn’t make sense to do that and now it does.”

Sociocultural Reasons

Sociocultural reasons for position identity change included greater exposure to the gay community; changes in geographical location; and change in the influence of perceived stigma and stereotypes, including those involving gender, power, and sexual orientation. Three participants noted that assimilation into gay culture moves one toward adopting position identities. One participant described his change from not having a position identity to identifying as “versatile” as a function of greater exposure to community norms: “I guess for me, it’s been a long-term, slow change from one environment that wasn’t as receptive of those ideas to one that is. I’ve been slowly adjusting over the years to a more receptive environment. So in every sense of it, my comfort has increased I guess for carrying that label internally. It’s sort of resonated with me. Maybe assimilation into gay culture in part too. Before, I didn’t see myself in the broader scope of community as much and now I do more, both the gay community and the broader community.” Participants also cited stereotypes associated with gender, power, and sexual orientation as a reason for changing position identities. Six participants cited gender stereotypes as motivating their change, including a participant who moved from not having a position identity to “versatile:” “I guess I wanted to be more masculine. I didn’t want to be gay. I fought against it for a very long time. My father didn’t want me to be gay.” Another participant similarly describes the influence of stereotypes on his position identity change, although in terms of his desire to remain or appear heterosexual: “When I first came out, there was this idea among gay men that I know, you know, to take steps to come to terms with your sexuality, I went from I’m a heterosexual man, to I’m a gay man, to I’m top. It was a way to still hang onto being heterosexual.” Participants also noted that stereotypes within the gay community also influenced their position identity changes, including the following participant who moved from “mostly bottom” to “versatile,” referencing the conflation of being a “bottom” with submissiveness within the gay community: “I’ve kind of tried to remove myself from this, but I think the power in the gay community, if you label someone as a bottom, there’s a stereotype revolving around that person. They’re more submissive, they’re the one that kind of takes it kind of a thing.”

Four participants noted that certain elements of different geographical locales and societies influenced their position identity change, as it did for one participant who moved between global regions over the study period: “When I was in Southeast Asia I found myself, when I would get aroused, the types of things I wanted to do were a lot more top-oriented, but here in the U.S., I find that switched around—the type of men I’m attracted to tend to feed into my desires of bottoming. But over there, the people who are out are very flamboyant and extreme because of lack of acceptance. Even though here in the U.S. I am more on the feminine bottom side, with all of those men there, I felt more of a top. It seems like a really weird sizing up kind of thing.”

Do Participants’ Changes in Sexual Position Identities Correspond to Changes in Position Behaviors and Fantasies?

Temporal patterns (i.e., change, stability) in sexual position identity significantly predicted certain changes in actual position during sex as recalled from the 30 days before Time 1 assessment and 30 days before Time 2 assessment. Since some position identity categories had very few participants (i.e., “exclusively bottom,” “exclusively top”), in these analyses we collapsed across related categories as described in the Data Analysis section above.

Twelve dummy-coded variables were created to capture participants who changed into, out of, and stayed in each of the four position identity categories (i.e., “top,” “bottom,” “versatile,” “no label”) across the 2 years. In the first regression analysis, we predicted frequency of receptive anal sex at Time 2 from these 12 variables controlling for frequency of receptive anal sex at Time 1. In the second regression analysis, we predicted frequency of insertive anal sex at Time 2 from these 12 variables controlling for frequency of insertive anal sex at Time 1. Overall, temporal position identity patterns predicted changes in receptive anal sex frequency, R 2 = .27 (SE = .88), p < .01. Specifically, participants who changed to “bottom” (β = .27, SE = .38, p < .05), from “bottom” (β = .30, SE = .50, p < .05), from “top” (β = .25, SE = .53, p < .05), or stayed “versatile” (β = .38, SE = .43, p < .05) reported more frequent receptive anal sex over time. Overall, temporal position identity patterns also predicted changes in insertive anal sex frequency, R 2 = .37 (SE = .87), p < .001. Specifically, participants who changed to “top” reported more frequent insertive anal sex over time (β = .28, SE = .34, p < .05). To rule out the possibility that the relationship between temporal position identity and behavior patterns reflected an association between position identity change and simply having more anal sex over time, we also predicted changes in the relative frequency of receptive to insertive anal sex from temporal position identity patterns. Specifically, we computed a variable to be the ratio of receptive anal sex frequency to insertive anal sex frequency for Time 1 and Time 2 and used these in parallel analyses as above. Results demonstrated that temporal position identity patterns predicted the relative frequency of receptive to insertive anal sex over time, R 2 = .30 (SE = .48, p < .0. Specifically, changing to “top” (β = .53, SE = .19, p < .001), staying “top” (β = .43, SE = .22, p < .001), changing to “no label” (β = .26, SE = .46, p < .05), staying “no label” (β = .27, SE = .18, p < .05), and changing to “versatile” (β = .39, SE = .28, p < .05) predicted an increase in the relative frequency of insertive to receptive anal sex over time.

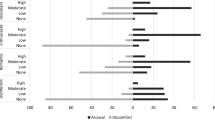

To assess temporal correspondence of position identity and fantasy patterns, we first counted the number of participants who showed the same position fantasy and identity pattern over time. For position identity, we collapsed “I have never labeled myself in these ways” with “I used these labels for myself in the past but not anymore,” as the latter option was not presented to participants for position fantasy. About one-quarter (n = 24, 25.8 %) showed the same temporal position fantasy and identity pattern, with 17 (70.8 %) of those participants retaining the same position identity and position fantasy over time (e.g., “versatile” identity and fantasies and both time points). Next, to predict temporal correspondence of fantasy and position identity pattern, we limited analyses to only participants who indicated a position fantasy at both time points (n = 78) and then predicted, from the 12 position identity dummy variables, these fantasies as a continuous variable with “exclusively top” and “exclusively bottom” serving as endpoints. Time 1 fantasies were included as a covariate. Overall, temporal position identity patterns predicted temporal fantasy patterns, R 2 = .47 (SE = .75), p < .001. However, change in fantasy only happened for those participants who stayed “top” (β = −.42, SE = .39, p < .05), stayed “versatile” (β = −.26, SE = .32, p < .05), and stayed “no label” (β = −.25, SE = .40, p < .05) across the 2 years. These participants showed a significant move toward “top” and away from “bottom “fantasies.

Discussion

Overview of Findings

The results of the present study suggest that sexual position identities are a highly relevant component of young sexual minority men’s sexuality that demonstrates considerable context-driven change over time. Over half of the study participants changed their sexual positioning identity over the 2 years of the study, with the average participant moving to the adjacent category in either direction when assessed with a dimensional approach. Using a more categorical approach with previous support (i.e., “top,” “bottom,” “versatile,” “no label”), more than one in three participants changed identities over the 2 years. Participants who initially did not endorse position identity labels at Time 1 demonstrated a significant move toward using these labels, in particular “versatile,” at Time 2. Participants also showed a significant move toward identifying as “mostly top” over time. Overall, participants offered numerous explanations for their identity changes referencing the influence of personal development, practical reasons, changing relationships, and sociocultural factors. Patterns of position identity stability and change were reflected, although imperfectly, in patterns in the actual positions participants take during anal sex across the study and largely not reflected in fantasy patterns over time. Our discussion of results returns to the conceptual framework proposed in the Introduction to explain the primary trends uncovered—that participants demonstrated a significant move toward adopting sexual position identities generally over time and toward identifying as “mostly top” in particular—in light of the personal, practical, relational, and sociocultural influences that participants cited to explain their position identity changes. We review these trends and their contextual influences, both individual and sociocultural, in discussing implications for future conceptualizations of sexual position identities and the possibility that static sexual position identities represent an ill-fitting taxonomy for capturing the contextually sensitive nature of young sexual minority men’s sexuality.

Implications

Both fluctuating and stable individual factors represent plausible explanations of position identity change. Roughly four-fifths of interviewed participants provided psychosocial explanations for their position identity change suggesting the important influence of fluctuating personal experiences (e.g., greater sexual experience, greater self-confidence) on position identities. Many fewer participants referenced body traits, race, and personality in explaining their changes. It is possible that these relatively more stable factors are more useful for explaining position identity stability, rather than change, although that possibility was not investigated here. Still, three participants described medical issues (e.g., rectal fissures), while two described partner penis size, both absolute and relative to the size of one’s own penis, as influencing their position identity change. Two participants mentioned increasing comfort with their sexual orientation as yielding changes in their position identities over time, tentatively suggesting the possible influence of decreasing internalized homophobia on position identity. It is further possible that increasing self-confidence and relational power, both cited as predictors of position identity change, also reflect decreasing internalized homophobia. However, the tendency across participants to move toward “mostly top” combined with previous research showing associations between internalized homophobia and a “top” identity (Hart et al., 2003), suggests that reductions in internalized homophobia may not fully explain position identity changes.

Returning to the sociocultural hypotheses guiding our investigation, we ask: Do static sexual position identity categories accurately represent the social organization of contemporary young sexual minority men’s sexuality or do they represent an ill-fitting taxonomy borrowed from irrelevant or outdated notions of binary gender and power enactments? Our sociocultural framework contradictorily suggests that some cultural forces (e.g., young sexual minority men’s possibility to transgress standard notions of gender and relational power) will encourage constant fluidity in position identities over time, while other cultural forces (e.g., the tendency of some parts of the gay community to embrace hegemonic masculinity) will encourage a general tendency for young sexual minority men to move toward adopting position identities and a “top” identity in particular. We found support for both possibilities.

Four findings suggest that sexual positioning identity categories may represent an ill-fitting scheme largely borrowing from standard notions of gender and power that artificially press an inherently fluid system of identity, fantasies, and behavior into supposedly fixed categories. First, about half of participants changed their sexual position identities over the relatively short span of 2 years citing 11 broad classes of reasons for doing so. This finding suggests that young sexual minority men’s use of sexual position identities cannot be reliably tied to any one source, such as traditional notions of gender, power, or any other supposedly fixed explanation. Second, one in three participants cited the constraining nature of labels as a reason for changing their position identity, including the undesirable potential for position identities to invoke stereotypes of gender and power. Third, at both assessment points, half of the participants identified as “versatile” or “no label,” with some citing the constraints of labels other than “versatile” for capturing their fluid desires and behaviors. Fourth, changes in position identity were not perfectly reflected in changes in preferred and actual sexual behavior, suggesting that position identities do not reliably capture other meaningful components of sexuality. Taken together, these findings suggest that sexual position identities do not represent fixed kinds and are not reliably associated with any other framework of sexual organization investigated here, at least for half of the participants in this study.

On the other hand, about half of the participants did not change their position identities over time and some of those who did change cited gender and power enactments as reasons for change. Additionally, participants showed a significant move toward adopting, rather than shunning, position identities over time and were significantly more likely to move toward a “mostly top” identity consistent with the reinforcement of traditionally masculine behaviors in the gay community. These findings, therefore, alternately suggest that while sexual position identities might represent an ill-fitting scheme for many young sexual minority men, other young sexual minority men may consistently find position identities useful, particularly for invoking traditional cultural expectations, such as polar enactments of gender and power during sex, even in the currently transgressive sphere of sex between men.

Participants cited social stigma and stereotypes as an important source of position identity change over time, suggesting that the sexuality of at least some young sexual minority men—more than one-third of the men we interviewed—is shaped by relatively rigid notions of gender, power, and sexual orientation held by others. Some participants noted, for example, that their choice of sexual position identity was influenced by gay-related stigma in broader society, for instance that being a “top” was a way to appear masculine or to “hang on to being heterosexual” thereby mirroring the conflation of sexual position and sexual orientation found in cultures outside of the U.S. (e.g., Carballo-Dieguez & Dolezal, 1994; Carrier, 1995). Participants also pointed to the gay community as a purveyor of stereotypes conflating sexual position identity with traditional notions of gender and power. These explanations for change combined with the trend for participants to move toward identifying as “mostly top,” suggest that sociocultural influences of the gay community might have an increasingly powerful influence on young sexual minority men’s position identity across development. Previous research pointedly notes the explicit and pervasive reinforcement of hegemonic masculinity in contemporary gay communities, especially in sexual domains (Bailey et al., 1997; Bartholome et al., 2000; Jeffries, 2009; Taywaditep, 2001). Given that gay men’s concerns about masculine self-presentation might compromise their health (e.g., Courtenay, 2000; Hamilton & Mahalik, 2009; Pachankis, Dougherty, & Westmaas, 2011) and psychological wellbeing (e.g., Sánchez & Vilain, 2012), future research ought to consider the possibility that sociocultural pressures to identify as “top” might predict changes in health. One notable correlate of identifying as a “bottom” found in previous studies is a higher likelihood of being HIV-positive (e.g., Wegesin & Meyer-Bahlburg, 2000). However, the results of the present study suggest that such cross-sectional findings regarding health correlates of position identities are in need of critical re-evaluation under a lens that treats position identities as dynamic constructs.

Limitations

This was the first prospective investigation of sexual minority men’s position identities and was also the first to prospectively establish change in the use of these identities over time and the correspondence of this change with changes in sexual position fantasies and behavior. This was also the first study to examine position identities among young sexual minority men specifically. Patterns of change were contextualized through in-depth qualitative interviews conducted with a subset of participants who changed position identities over 2 years. The findings presented here, however, cannot be generalized to a sample of older sexual minority men, men with lower levels of educational attainment, or young sexual minority men who were never active in college campus LGBT groups—the recruitment source utilized in this study. Young sexual minority men may differ from older sexual minority men in numerous ways, particularly in their developmental narratives of sexuality and the possibility that younger sexual minority men might be negotiating their identities more than older sexual minority men (e.g., Cohler & Hammack, 2007). Future longitudinal studies of sexual minority men’s sexual position identities will ideally follow multiple age cohorts of men over numerous assessment points, while continuing an approach of contextualizing participants’ use of position identity terms. Indeed, a “bottom” today is not necessarily a “bottom” 10 years ago, not only in terms of one’s identification, as shown in this study, but also in the historically-dependent meaning of the term, including associations with HIV risk and the changing meanings of that risk over time (Odets, 1995).

Future studies should include a larger sample than utilized here, especially given our significant attrition across 2 years and the fact that many of the categories used in our quantitative analyses included a small number of participants, while our qualitative findings derive from only 28 participants. Oversampling participants from traditionally underrepresented racial and ethnic groups would allow exploration of the ways in which the use of sexual position identities varies over time according to the cultural influences specific to these groups. Future research will also ideally clarify the degree to which position identity is best conceptualized as a dimensional or categorical construct, as the present study utilized both conceptualizations at times for the sake of organizing the data. Further, we examined anal sex as the only behavioral correlate of sexual position identity; however, the possibility exists that sexual position identity may also be reflected in other forms of sexual behavior, such as oral sex, which could be examined alongside anal sex in future investigations.

Implications for Future Research

Previous research using older samples of sexual minority men has typically presented sexual positioning terms (e.g., “top,” “bottom,” “versatile”) to participants as if these are essential categories. However, the results of the present study suggest that young sexual minority men’s use of these identities is frequently, if not usually, dependent on context. Thus, future researchers might wish to consider capturing the function of those terms for participants alongside their specific contexts relevant to the research purpose at hand. Further, the present study is the first to examine sexual minority men’s sexual positioning as composed of identity, behaviors, and fantasies, and future researchers might wish to consider more clearly specifying which of these components they set out to examine rather than assuming unity among these components as has largely been done to date. Interestingly, the participants we interviewed variably referred to their sexual position as an identity (e.g., “I am a bottom…”) and a behavior (e.g., “I bottom…”). While we did not set out to examine factors determining when one used his position label as an identity versus as a behavioral descriptor, future researchers might wish to investigate the implications that these different conceptualizations of sexual position might have on sexual minority men’s self-concept, health, and well-being.

While the results of this study present a strong argument that sexual position identities are socially constructed, these findings cannot rule out the possibility that position identities reflect innate tendencies. While a preliminary biological distinction between “butch” and “femme” lesbians has been reported (Brown, Finn, Cooke, & Breedlove, 2002; Singh, Vidaurri, Zambarano, & Dabbs, 1999), only future research will be able to establish whether any natural substrate underlies the sexual position identities used by sexual minority men. Any research into “natural” explanations for sexual minority men’s position identities ought to consider the possibility that a biological underpinning might be more likely to be found among sexual minority men who retain their position identities over time, as about half of our participants did over a 2-year span. On the other hand, participants who retain their identity over time may in fact be those participants who adhere most strongly to cultural systems of sexual categorization, regardless of any biological predisposition toward one identity or another. Still, the discovery of a biological underpinning of sexual positioning categories would not vitiate our view that position identities are shaped by cultural forces, as all personal identities are (e.g., Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Our qualitative findings reviewed above suggest what those forces may be.

Conclusion

Forms of human sexual expression are inherently dependent on socio-historical context (Hammack, 2005) and current trends point to increasing fluidity among sexual categorization schemes among sexual minority individuals (e.g., Diamond, 2008). Still, most research capturing this movement has been limited to women’s sexuality, particularly women’s partner gender preferences and associated behaviors and identities. The results of the present study suggest that young sexual minority men also fluidly engage a system of sexual categorization, namely sexual position identity categorization, placing an important boundary around the extent to which men’s sexuality can be assumed to be relatively independent of social influence compared to women’s (Baumeister, 2000). This study, therefore, adds to a nascent body of research showing that the sexuality of men in contemporary U.S. society may be more fluid and context-dependent than previously assumed (e.g., Preciado, Johnson, & Peplau, 2013). Whether these findings are isolated to young sexual minority men’s sexual position identities or represent a harbinger of greater fluidity among other components of all men’s sexuality remains to be discovered.

References

Bailey, J. M., Kim, P. Y., Hills, A., & Linsenmeier, J. A. W. (1997). Butch, femme, or straight acting? Partner preferences of gay men and lesbians. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 960–973.

Bartholome, A., Tewksbury, R., & Bruzzone, A. (2000). ‘‘I want a man’’: Patterns of attraction in all-male personal ads. Journal of Men’s Studies, 8, 309–321.

Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Gender differences in erotic plasticity: The female sex drive as socially flexible and responsive. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 247–374.

Bieber, I., Dain, H. J., Dince, P. R., Drellich, M. G., Grand, H. G., Gundlach, R. H., … Bieber, T. B. (1962). Homosexuality: A psychoanalytic study. New York: Basic Books.

Boxer, A. M., & Cohler, B. J. (1989). The life course of gay and lesbian youth: An immodest proposal for the study of lives. Journal of Homosexuality, 17, 315–355.

Brown, W. M., Finn, C. J., Cooke, B. M., & Breedlove, S. M. (2002). Differences in finger length ratios between self-identified ‘butch’ and ‘femme’ lesbians. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 31, 123–127.

Carballo-Dieguez, A., & Dolezal, C. (1994). Contrasting types of Puerto Rican men who have sex with men (MSM). Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 6, 41–67.

Carrier, J. M. (1995). De Los Otros: Intimacy and homosexuality among Mexican men. New York: Columbia University Press.

Chauncey, G. (1994). Gay New York: Gender, urban culture, and the making of the gay male world, 1890–1940. New York: Basic Books.

Chivers, M. L., Rieger, G., Latty, E., & Bailey, J. M. (2004). A sex difference in the specificity of sexual arousal. Psychological Science, 15, 736–744.

Cohler, B. J., & Hammack, P. L. (2007). The psychological world of the gay teenager: Social change and the issue of “normality.”. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 47–59.

Courtenay, W. H. (2000). Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science and Medicine, 50, 1385–1401.

Diamond, L. M. (2003). What does sexual orientation orient? A biobehavioral model distinguishing romantic love and sexual desire. Psychological Review, 110, 173–192.

Diamond, L. M. (2008). Female bisexuality from adolescence to adulthood: Results from a 10-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 44, 5–14.

Grov, C., Parsons, J. T., & Bimbi, D. S. (2010). The association between penis size and sexual health among men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 788–797.

Haist, M., & Hewitt, J. (1974). The butch-fem dichotomy in male homosexual behavior. Journal of Sex Research, 10, 68–75.

Hamilton, C. J., & Mahalik, J. R. (2009). Minority stress, masculinity, and social norms predicting gay men’s health risk behaviors. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 132–141.

Hammack, P. L. (2005). The life course development of human sexual orientation: An integrative paradigm. Human Development, 48, 267–290.

Harry, J., & DeVall, W. B. (1978). The social organization of gay males. New York: Praeger.

Hart, T. A., Wolitski, R. J., Purcell, D. W., Gòmez, C., & Halkitis, P., & The Seropositive Urban Men’s Study Team. (2003). Sexual behavior among HIV-positive men who have sex with men: What’s in a label? Journal of Sex Research, 40, 179–188

Hooker, E. (1965). An empirical study of some relations between sexual patterns and gender identity in male homosexuals. In J. Money (Ed.), Sex research: New developments (pp. 24–52). New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Hoppe, T. (2011). Circuits of power, circuits of pleasure: Sexual scripting in gay men’s bottom narratives. Sexualities, 14, 193–217.

Jeffries, W. L. (2009). A comparative analysis of homosexual behaviors, sex role preferences, and anal sex proclivities in Latino and non- Latino men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 765–778.

Kimmel, M. (1996). Manhood in America: A cultural history. New York: Free Press.

Kippax, S., & Smith, G. (2001). Anal intercourse and power in sex between men. Sexualities, 4, 413–434.

Kroger, J., Martinussen, M., & Marcia, J. E. (2010). Identity status change during adolescence and young adulthood: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 33, 683–698.

Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J. H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels, S. (1994). The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224–253.

McClintock, M. K., & Herdt, G. (1996). Rethinking puberty: The development of sexual attraction. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 5, 178–183.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Moskowitz, D. A., & Hart, T. A. (2011). The influence of physical body traits and masculinity on anal sex roles in gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 835–841.

Moskowitz, D. A., Rieger, G., & Roloff, M. E. (2008). Tops, bottoms, and versatiles. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 23, 191–202.

Odets, W. (1995). In the shadow of the epidemic: Being HIV-negative in the age of AIDS. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Pachankis, J. E., Westmaas, J. L., & Dougherty, L. R. (2011). The influence of sexual orientation and masculinity on young men’s tobacco smoking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79, 142–152.

Peplau, L. A. (2003). Human sexuality: How do men and women differ? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 37–40.

Peplau, L. A., Spalding, L. R., Conley, T. D., & Veniegas, R. C. (1999). The development of sexual orientation in women. Annual Review of Sex Research, 10, 70–100.

Plummer, K. (1995). Telling sexual stories: Power, change and social worlds. New York: Routledge.

Preciado, M. A., Johnson, K. L., & Peplau, L. A. (2013). The impact of cues of stigma and support on self-perceived sexual orientation among heterosexually identified men and women. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

Saghir, M., & Robins, E. (1973). Male and female homosexuality: A comprehensive investigation. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

Sanchez, F. J., & Vilain, E. (2012). “Straight-acting gays”: The relationship between masculine consciousness, anti-effeminacy, and negative gay identity. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 111–119.

Savin-Williams, R. C. (2006). Who’s gay? Does it matter? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15, 40–44.

Savin-Williams, R. C., Joyner, K., & Rieger, G. (2012). Prevalence and stability of self-reported sexual orientation identity during young adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 103–110.

Silverstein, C. (1981). Man to man: Gay couples in America. New York: Morrow.

Singh, D., Vidaurri, M., Zambarano, R. J., & Dabbs, J. M, Jr. (1999). Lesbian erotic role identification: Behavioral, morphological, and hormonal correlates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 1035–1049.

Stein, E. (1999). The mismeasure of desire: The science, theory, and ethics of sexual orientation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Taywaditep, K. J. (2001). Marginalization among the marginalized: Gay men’s anti-effeminacy attitudes. Journal of Homosexuality, 42, 1–28.

Tripp, C. A. (1975). The homosexual matrix. New York: McGraw-Hill.

U.S. Department of Education. (2010). Institute of Education Science, National Center for Education Statistics [Data file]. Retrieved from http://nces.Ed.gov/ipeds/

Vrangalova, Z., & Savin-Williams, R. C. (2012). Mostly heterosexual and mostly gay/lesbian: Evidence for new sexual orientation identities. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 85–101.

Wegesin, D. J., & Meyer-Bahlburg, H. F. L. (2000). Top/bottom self-label anal sex practices, HIV risk and gender role identity in gay men in New York City. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 12, 43–62.

Wei, C., & Raymond, H. F. (2011). Preference for and maintenance of anal sex roles among men who have sex with men: Sociodemographic and behavioral correlates. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 829–834.

Weinrich, J. D., Grant, I., Jacobson, D. L., Robinson, S. R., McCutchan, J. A., & The HNRC Group. (1992). Effects of recalled childhood gender nonconformity on adult genitoerotic role and AIDS exposure. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 21, 559–585.

Zheng, L., Hart, T. A., & Zheng, Y. (2012). The relationship between intercourse preference positions and personality traits among gay men in China. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 683–689.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lea Dougherty, Mark Hatzenbuehler, and Letitia Anne Peplau for providing helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pachankis, J.E., Buttenwieser, I.G., Bernstein, L.B. et al. A Longitudinal, Mixed Methods Study of Sexual Position Identity, Behavior, and Fantasies Among Young Sexual Minority Men. Arch Sex Behav 42, 1241–1253 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0090-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0090-4