Abstract

What explains the persistent growth of public employment in reform-era China despite repeated and forceful downsizing campaigns? Why do some provinces retain more public employees and experience higher rates of bureaucratic expansion than others? Among electoral regimes, the creation and distribution of public jobs is typically attributed to the politics of vote buying and multi-party competition. Electoral factors, however, cannot explain the patterns observed in China’s single-party dictatorship. This study highlights two nested factors that influence public employment in China: party co-optation and personal clientelism. As a collective body, the ruling party seeks to co-opt restive ethnic minorities by expanding cadre recruitment in hinterland provinces. Within the party, individual elites seek to expand their own networks of power by appointing clients to office. The central government’s professed objective of streamlining bureaucracy is in conflict with the party’s co-optation goal and individual elites’ clientelist interest. As a result, the size of public employment has inflated during the reform period despite top-down mandates to downsize bureaucracy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Public positions are expected to serve public functions, yet in reality they are often created to support private interests. As Geddes states, “The bureaucracy’s main function was not the provision of public service but the provision of private services” (1994, pp. 45, emphasis added). Being excludable and reversible, public jobs are especially amendable to targeting and exchange (Magaloni et al. 2007; Robinson and Verdier 2013). Hence, in both competitive democracies and electoral autocracies, politicians commonly exploit public employment to buy votes and to solidify hegemonic parties (Calvo and Murillo 2004; Geddes 1994; Kitschelt 2000). However, in the case of single-party dictatorships, in which competing political parties and electoral pressures are absent, we know little about whether—or how—politics drive the creation and allocation of public employment. This article fills this gap by examining the paradox of bureaucratic expansion following market liberalization in China.

Two patterns of public employment in post-1978 China are striking. First, the number of public administrative personnel has risen steadily during the era of market reforms, reaching a total of nearly 50 million public employees by 2007. To put this figure in context, the total bureaucratic workforce in China is equivalent to the entire population of South Korea. As China transitioned from a centrally planned to a market economy, observers might expect to see a reduction of state presence; in fact, the bureaucracy has grown dramatically, despite the central government’s repeated, vigorous efforts to reduce it.

Second, the size and rate of public employment varied widely across provinces. From 1997 to 2007, Tibet averaged 57 cadres for every 1000 residents, compared to 27 in Anhui province. In 2007, Beijing recorded the highest spike in public employment, an addition of almost a quarter million staff members, while Qinghai province added only 4000 more positions in the same year. Some have interpreted the growth of bureaucracy as evidence of the loss of central control over local governments (Bernstein and Lü 2003; Lü 2000; Pei 2006). But there has not yet been a systematic attempt to account for such striking regional variance in public employment.

Existing accounts highlight several political factors that cannot satisfactorily explain the national and regional patterns observed in China. The first centers on the effects of party-based patronage among post-communist states. O’Dwyer observes that bureaucracies in Eastern Europe experienced similar surges following the fall of communism. He attributes this paradox to “patronage politics,” in which newly formed parties sought to secure support by disbursing public sector jobs to their constituents (2006, p. 2). Grzymala-Busse (2007) finds that robust competition prevented fledging political parties in Eastern Europe from exploiting state administrations as a source of party largess, thus explaining less bureaucratic bloat in competitive regimes. Although these accounts shed useful light on the situation among post-communist democracies, they have limited applicability in China, where the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) remains the only political party in power.

A second set of explanations shifts the agency of patronage from political parties to individual dictators and political elites. Authoritarian regimes are characterized by personalist rule and dyadic patron-client relations, also known as “factionalism” in Chinese politics (Nathan 1973; Shih 2008). Dictators are known to dispense particularistic benefits to loyal clients in order to strengthen and maintain personal power, as depicted in the “political exchange” model of dictatorship (Wintrobe 1998). Following this logic, a study of the former Soviet Union argues that the leadership had allocated the scarce resource of cars on the basis of political loyalties to Stalin, rather than the objective criteria of “economic planning” (Lazarev and Gregory 2002, 2003).

Yet a third body of theories point to non-political factors affecting public employment. According to Wagner’s Law, areas with a higher level of economic wealth and urbanization should feature larger bureaucracies because complex economies require extensive administration and thus more public personnel (Wagner 1883). Public employment is thus correlated with larger demands for public services provisions. Further, some claim that the provision of fiscal transfers by higher-level governments encourages localities to inflate hiring (Gimpelson and Treisman 2002; Shih and Zhang 2006).

My analysis seeks to evaluate the role of political and non-political factors in shaping public employment within China’s single-party dictatorship. To do this, I assemble an original dataset on sub-national (provincial-level) public employment. To my best knowledge, this dataset, which draws on a primary source compiled by the Ministry of Finance (MOF), provides the most comprehensive and reliable measure of public employment in China to date.Footnote 1 Bearing remnants of its socialist past, the system of public hiring in China departs from standard public administrations in several ways.Footnote 2 Thus, it is important to understand the institutional details and the measurements provided by the source before applying statistical analyses. To that end, interviews with 38 public personnel managers usefully inform my interpretation of the data.

I find evidence that political factors—in particular, the dynamics of party co-optation and personal clientelism—dominate non-political factors in shaping the aggregate growth and regional distribution of public employment in China. By co-optation, I refer to strategic efforts undertaken by dominant political parties to align the interests of the potential opposition with their own. A major political threat facing the CCP is unrest among ethnic minority groups concentrated in the hinterland provinces. To co-opt these groups, the CCP disproportionately expands cadre recruitment in minority-dominant provinces that pose credible secessionist threats.

By personal clientelism, I refer to dyadic exchanges of loyalty and support for particularistic benefits between individual patrons and clients within the party state. Even as a hegemonic party, the CCP does not always act as a single cohesive unit that strategically distributes resources to maintain the party’s power. The ruling party itself is comprised of numerous political elites who are in competition with one another (Lu and Landry 2014; Shih 2008; Shirk 1982), each seeking to extend his or her own networks of power. Consistent with the logic of personal clientelism, I find that leadership turnover at the provincial level substantially accelerates bureaucratic growth, especially in the quasi-marketized segment of bureaucracy with the financial flexibility for discretionary hiring.

Instead of viewing party co-optation and personal clientelism as substitutes for each other, these two dynamics are better understood as a set of nested distributive politics that characterize authoritarian regimes. In China, competing elites are nested in a formal bureaucratic hierarchy. As a collective, the ruling party formulates national policies of redistribution to exert control. Within the party, individual elites seek to advance their personal agendas and clientelist networks. When competing elites are nested within a formal bureaucratic hierarchy, national and individual goals of distribution coexist in tension.

Once the nested nature of distributive politics in authoritarian China is highlighted, it is no surprise that the bureaucracy has inflated despite top-down mandates to reduce it. The central government’s professed target of streamlining administration is in conflict with the party’s political goal of co-opting opposition groups and with individual elites’ recruitment of clientele through appointments.

The first section of this article discusses how party co-optation and personal clientelism drive public employment in China. The second section introduces the data, measurements, and descriptive patterns. The third section presents the results of a multivariate analysis of the factors that shape public employment patterns. Finally, I conclude in the fourth section with the implications for central-local relations and bureaucratic reforms.

Co-optation and Clientelism in China

One-party (single-party and dominant-party) regimes combine strategies of institutional co-optation and mass clientelism to survive (Magaloni and Kricheli 2010). Although both co-optation and clientelism constitute exchange-based strategies, the targets of exchange are different. Co-optation is carried out by ruling organizations to appease or to win over opposing groups through the provision of particularistic benefits or power-sharing arrangements (Blaydes 2010; Gandhi 2008; Lust-Okar 2005; Malesky and Schuler 2010). Co-optation may be carried out simultaneously with repression; but, whereas repression involves sticks, co-optation entails distributing carrots. By comparison, clientelism is targeted at individual citizens, rather than at dissident segments of society, and material benefits are typically exchanged for votes (Hicken 2011). More recently, clientelism has been employed by political parties on an organized scale to ensure continuous re-election, which is termed “mass clientelism” or “machine politics” (Magaloni 2006). Patronage is a subset of clientelism, where patrons who provide benefits are office holders or can access state resources (Hicken 2011; Stokes 2007).

Much of the literature on co-optation and clientelism centers on electoral regimes, which are marked by formal political contests. However, in a single-party dictatorship like China, where competitive national elections are entirely absent, co-optation and clientelism takes on a different flavor. Being a single-party dictatorship, the CCP need not contend or share power with other political parties. However, it fears unrest among and challenges against its hegemonic power from restive segments of society. In this article, I focus on the party’s co-optation of a subset of ethnic minorities (and I will later explain this choice). However, it should be noted that the CCP has also attempted to coopt other influential groups—most notably, wealthy private entrepreneurs—by enlisting them to join the party or to serve as delegates in legislative congresses (Dickson 2008; Tsai 2007). Within the CPP, national leaders may also co-opt independent-minded regional leaders by appointing them to central decision-making bodies (Sheng 2009).

With the rise of modern political parties, the literature on clientelism has shifted from an earlier focus on dyadic patron-client relations toward “mass clientelism” (or organized vote buying), as seen in electoral autocracies like Mexico under the PRI (Magaloni 2006). Given the absence of elections in China, clientelism continues to prevail in the form of “vertical dyadic alliances:” personal and instrumental ties of exchange between two individuals of unequal power and status (Lande 1977, p. xx). In the Chinese context, such dyadic alliances can be found among the highest ruling elites (Nathan 1973), within sub-national bureaucracies (Hillman 2010) and in the grassroots of society (Oi 1989; Walder 1986). Among elites, patronage networks aid survival in times of political purges (Nathan 1973; Tsou 1995). Such ties are also closely connected to corruption, as higher- and lower-level officials, along with wealthy capitalists, rely upon one another to capture rents. Patronage is also a tool of policy implementation. Within villages and urban work units, higher-level officials can count on clients at the lower levels as “their most enthusiastic supporter [s] and helper [s]” (Oi 1985, p. 257).

Although party co-optation and personal clientelism have each been extensively discussed by China scholars, co-optation and clientelism have rarely been examined side-by-side. This is surprising, because as several classical studies reveal (Nathan 1973; Walder 1986), informal patron-client ties are nested within the formal hierarchy. In Andrew Nathan’s words, “the hierarchy and established communications and authority flow of the existing organization provides a kind of trellis upon which the complex faction is able to extend its own informal, personal loyalties and relations” (1973, p. 44).

Analogous to the dynamics of nested distributive politics in authoritarian China is the “broker-mediated model of clientelism” found in some democracies (Stokes et al. 2013). At times a disjunction emerges between the distributive goals of national party leaders and local brokers; the former prefers targeting particularistic goods at swing voters, whereas the latter favors loyal supporters in their home jurisdictions. However, the broker-mediated model features the national party (equivalent to the central party state in China) and local brokers as two separate and distinct actors. In contrast, in China, central authorities are known to be divided into factions that hold one another in check. Each faction at the helm is then vertically connected, level by level, to a vast network of subnational clientele.

The view of authoritarian party state described above defies the conventional image of dictatorships, which equate the dictatorial regime with a particular dictator or circle of ruling elites (Gandhi 2008; Wintrobe 1998).Footnote 3 I advance a more disaggregated view of dictatorships. Simultaneously, I stress that informal relationships are the invisible glue that binds the formal hierarchy. Thus, in the next section, I discuss how two nested sets of distributive politics—personal clientelism and party-based co-optation policies—jointly shape public employment patterns.

Party Co-optation: the Ethnic Factor

As a single party, the CCP commands monopoly of power to co-opt groups that may challenge its hegemony. The most common tactic is to urge influential and potentially subversive individuals to join the ranks of the party and the administration (Li and Walder 2001). In this analysis, I focus on the co-optation of ethnic minorities through bureaucratic (cadre) recruitment. Why ethnic groups? China is populated by a majority of Han people and has over 55 minority groups. Minority groups concentrated in the hinterland western provinces, such as Tibetans in Tibet and Uyghurs in Xinjiang, have fervently resisted national incorporation and repression. Protests, violent crackdowns, and activities labeled by the CCP as “terrorism” have rocked the hinterland provinces, posing a grave threat to national unity and regime stability (Kerr and Swinton 2008). The logic of co-optation may be extended to other groups who have resources or cause to agitate for political change, such as private entrepreneurs. However, in co-opting the entrepreneurial class, the CPP doles out patronage in the form of party membership and congressional seats (Dickson 2008), not full-time public jobs.

Party co-optation of ethnic minorities is an open policy that the CCP advertises with pride as “affirmative action” (Sautman 1998; Zang 2010). Indeed, the prioritization of ethnic politics is evident in the party’s organizational structure—the Office of Ethnic Minority Affairs is a core party organ, which extends from the central level down to the counties and townships. Mao Zedong, the CCP’s founding leader, pointedly expressed the party’s rationale for co-opting minorities in a telegraph addressed to provincial party chiefs in 1949: “State organs at all levels of administration should allocate slots based on the population of ethnic minorities, absorb Muslims and other minorities in large numbers who can cooperate with us to join the bureaucracy… It is impossible for our party to do without large numbers of ethnic minority communist cadres” (Mao 1978).

Ethnic co-optation in China takes a page from the former Soviet Union’s strategy of ethno-politics. Indigenous cadres act as “sanctioned political entrepreneurs,” whose personal success was tied to the success of the party (Roeder 1991). Giving minorities positions in the party-state apparatus allows them to participate in decision-making and to benefit economically from CCP rule. As intermediaries, indigenous cadres transmit state policy to their communities and relay local sentiments back to higher levels. Importantly, although the state administration in minority-dominant locales is headed by an ethnic minority, the top post of party secretary is reserved for Han Chinese (Bovingdon 2010, p. 449). Through this arrangement of dual leadership, the Han-based CCP retains ultimate authority over the governmental hierarchy in minority-dominant regions.

However, not all regions with ethnic minority populations should receive equal preferential treatment from the central party leadership. As recorded in the China Statistical Yearbooks, there are 20 among 31 provinces that register a non-negligible share of ethnic minorities. Among them, only Tibet, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia are hinterland provinces that share borders with a neighboring country. These three provinces can credibly seek independence and build connections with transnational ethnically based organizations (Bovingdon 2010). It is consistently reported across studies of ethnic politics that ethnic nationalist groups and bloody crackdowns are concentrated in Tibet, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia (Bovingdon 2010; Bulag 2002; Schwartz 1994). By comparison, the remaining provinces feature a diverse mosaic of minority groups (e.g., Miao or Zhuang), which are neither militant nor politically organized. Minority groups in landlocked provinces like Gansu cannot feasibly demand secession from the mainland. Although there may be occasional sporadic clashes in these provinces, such tensions have not involved calls for independence or transnational groups.

Personal Clientelism: the Leadership Factor

Communist dictatorships concentrate distributive power in the hands of particular individuals—thus, personal clientelism is deeply embedded within the formal hierarchical structure (Oi 1985; Walder 1986). For Chinese officials, a foremost means of securing power is to appoint favored candidates to office.Footnote 4 As Hillman describes in the context of a county government, “Dispensing patronage allowed [local bosses] to advance in the local state hierarchy and recruit supporters into positions beneath them as they rose… These informal networks became an essential source of political power” (2010, p. 5).

While it would be little surprise to find leadership turnover associated with bureaucratic expansion, what remains to be known is the size of this effect. Two features of China’s single-party system may generate a sizable accretion effect of leadership turnover on bureaucratic growth. First, single-party dictatorships fuse party and administration. They do not have a formal system of temporary political appointees who are separate from the regular civil service. This institutional feature means that any appointee becomes a permanent part of the party-state bureaucracy, even after the appointing patron has left his or her original post for another position, and these appointees accumulate with each round of leadership turnover. Second, members of the Chinese bureaucracy enjoy de facto lifetime tenure. Following communist ideological norms, cadres occupy a special privileged position in society (Lee 1991). Expectations of an “iron rice bowl” are deeply entrenched among public employees. Interviewees reiterate that removal only happens if a cadre is proven to have committed grievous errors or crimes, a rule that has become formally enshrined in the Civil Service Law.

Further, it should be emphasized that clientelism is not limited only to those at the helm of power—each appointed agent may in turn appoint sub-clients to office. China’s party-state hierarchy is massive and decentralized (Landry 2008), with five levels of government. One may compare elites at each level of the hierarchy to brokers. Opportunities and benefits emanate from the ruling party and flow down through a layered network of brokers. As Oi observed in the context of rural China, “Comparisons may be drawn between socialist patrons and the party bureaucrats… who become ‘political brokers’ through the distribution of party-controlled goods. An essential difference, however, is that in the Chinese socialist case there is only one party” (1985, p. 263).

Observable Implications

To summarize, combining my discussions above, I expect to observe the following patterns in the empirical analysis that follows:

-

(1)

All things equal, Tibet, Xinjiang, and Mongolia hire more public employees than other provinces.

-

(2)

Other provinces with minority populations do not hire significantly more public employees than provinces without minority populations.

-

(3)

Leadership turnover is associated with a higher rate of public employment expansion.

While party co-optation of ethnic minorities through cadre recruitment and clientelist appointments are both qualitatively established in the literature, my analysis aims to evaluate the magnitude of these political factors in influencing public employment patterns.

Data, Measures, and Descriptive Patterns

For this study, I assembled a unique panel dataset on public employment from 1997 to 2007 using data compiled by the Ministry of Finance (MOF).Footnote 5 The original data source is aggregated at the provincial level, which means that the number of employees in each province includes provincial and sub-provincial (cities, counties, and townships) employment. More details about the dataset are included in an online appendix.

The data used in this study offer several advantages. Among all the available sources, the MOF data is the most comprehensive and accurate count of public employment (Ang 2012). Instead of counting only selected government sectors, as reported in the Statistical Yearbooks (Burns 2003; Lü 2000; Yang 2004), or the number of officially approved positions, the data source measures the actual number of public employees, both state-funded and self-funded through nontax revenue.Footnote 6 Also, the dataset measures the number of personnel in the entire bureaucracy, not merely the top layer of party secretaries and state chiefs (Guo 2009; Lu and Landry 2014). This is worth emphasizing because leading officials, numbering about 500,000 individuals (Walder 2004), make up only a small percentage of the entire bureaucracy of almost 50 million individuals.

I must make clear what is absent in the data source, which limits my analyses. First, this is a province-level dataset. The original data source only reports the aggregated size of public employment at the provincial level, but it does not break down the numbers by sub-provincial levels of government. Second, this is not an individual-level dataset. The original source reports total public employment by province, but there is no indication of the identities of individual public employees (e.g., ethnic identities, party membership, education levels). Third, there is no information about which person or department is the hiring unit. The absence of individual level attributes of public employees precludes fine-grained testing of the exact mechanisms of public hiring. The data will only allow us to test the broad observable implications laid out in the previous section.

Defining the Scope of Public Employment

My measurement of public employment follows the conventional approach of including only employees in the public administration, excluding those in state-owned enterprise (SOE) and the military (Gimpelson and Treisman 2002; Grzymala-Busse 2007; Heller et al. 1984; O’Dwyer 2006). Specifically, China’s public administration consists of core party-state organs, which constitute the formal civil service, and an array of subsidiary organizations labeled here as extra-bureaucracies (shiye danwei). Extra-bureaucracies include regular public service providers like schools and hospitals, but also offices involved in administration, regulation, fee collection, and the provision of semi-commercialized services.Footnote 7 While core agencies are fully-funded with state budget appropriations, extra-bureaucracies are not guaranteed state funding. Instead, the latter can generate income by collecting regulatory fees and user charges or by selling services for profit.

Extra-bureaucracies are an attractive vehicle for public hiring because they enjoy more financial flexibility and looser recruitment rules than the formal civil service. By virtue of their direct ties to supervising state agencies, extra-bureaucracies enjoy quasi-monopoly privileges or competitive market advantages (Ang 2015). Such organizations are not unique to China. Other post-communist Eastern European governments also saw a proliferation of parastatal organizations that thrived on concessions, licenses, and exemptions (Grzymala-Busse 2007, p. 159). Additionally, whereas there are written rules and examinations governing appointments in the civil service, the recruitment criterion is looser among extra-bureaucracies. Later, in my analysis, I divide public employees into two categories: (1) administrative personnel: employees of core party-state organs who perform only administrative functions and (2) subsidiary personnel: employees of extra-bureaucracies who play a mixture of administrative and market roles.

Patterns of Public Employment: Aggregate Growth and Regional Distribution

Figure 1 shows a relentless rise in the absolute and relative size of public employment. In fact, the pace of expansion was faster following than before market liberalization in 1978. This is paradoxical given the expectation that a retreat from central planning should be followed by a reduction in the size of the state.Footnote 8 Moreover, the bureaucracy grew persistently despite five major downsizing campaigns initiated by the central government in 1982, 1988, 1993, 1998, and 2003. Each time, authorities in Beijing would harshly criticize bureaucratic sprawl and take draconian measures to curb its inflation. For example, during the 1998 downsizing campaign led by Premier Zhu Rongji, reputed to be a fierce reformer, the central government abolished 15 ministries and slashed the number of departments in the State Council (the top political organ of the state administrative hierarchy) from 72 to 53. Nationwide, the number of officially approved positions (bianzhi) was cut by an impressive 47.5 %.Footnote 9 And yet the actual number of public personnel continued to climb.

Comparatively speaking, the total size of public employment as a share of population in China is still smaller than in the OECD states and on par with countries in Latin America (Ang 2012). However, the size of China’s sub-national public employment relative to population is among the highest in the world. During the reform period, sub-national governments constituted 84 % of China’s total public workforce. Notably, subsidiary extra-bureaucracies hired an overwhelming share of public employees, about 80 %.

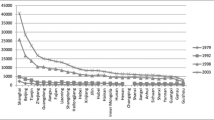

Public employment is widely distributed across the 31 provinces in China (see Fig. 2). Between 1997 and 2007, the average province hired 1.44 million public employees or 39 public employees per 1000 residents. Tibet has the highest ratio of public employment at 57.20 per 1000 residents, compared to 26.64 in Anhui. Figure 2 shows the high density of public employment in the hinterland, minority-dominant provinces of Tibet, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia (TXM for short). There is a strong correlation of 0.46 between TXM and public employment per 1000 residents, compared to 0.08 with minority share of population. The provinces also varied widely in the growth rate of public employment, as seen in Fig. 3. On average, 34,725 positions (or 0.58 public employees per 1000 residents) were added in each province, an annual increment of 2 % over the previous year. Beijing and Hunan tied for the highest growth rate at 1.36 public employees per 1000 residents. In the regressions that follow, I control for a range of factors to isolate the effects of the predicted variables.

Multivariate Analysis

In this section, I examine observable implications spelled out in the first section, using a multivariate analysis of cross-sectional time-series data. I use an OLS model with panel-corrected standard errors that correct for heteroskedasticity and spatial correlation (Beck and Katz 2006). Dummies for each year are added to control for year-specific shocks (e.g., a centrally mandated downsizing campaign or ethnic protest). I specify the dependent variable of public employment in two ways. First, to examine geographical distribution, I measure the dependent variable as public employees per 1000 residents. Second, to study the rate of expansion, I measure the dependent variable as change in public employees per 1000 residents and change in the total number of public employees.

The key independent variables are as follows. To capture the ethnic factor, I created a dummy variable for Tibet, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia (TXM). To assess if these provinces have more preferential treatment than other provinces with minority populations, I include an additional variable, share of minority population. Next, to measure leadership turnover, I created a dummy variable for new provincial leader in office. At every level of administration, the provincial party secretary (chief of party) and provincial governor (chief of state) are the two top political leaders. Whenever a new party secretary and/or governor arrive in office, I record that as a change in leadership.

Control Variables

For control variables, I include population, GDP per capita, urbanization, local dependency ratio, and total (elementary and secondary) school enrollment. Wagner’s Law hypothesizes that more developed and urbanized locations will need bigger bureaucracies to serve complex tasks of administration. Public employment growth may also reflect a higher demand for public services. Dependency ratio measures the percentage of local population younger than 16 and older than 64 years old. Presumably, the higher the percentage of the local population who are young and old, the more demand there is for public services (e.g., schools, clinics, and welfare centers). I also include the size of school enrollment to isolate the effects of demand for public education, as teachers make up a considerable share of public employment. To test for fiscal effects, I include the previous year’s per capita tax revenue, fiscal transfers, and extra-budgetary revenue, which are the three major fiscal categories in China. Finally, I tested the regressions with a battery of other controls (including reported unemployment rates and regional trade openness). As these were found insignificant, I excluded them for brevity. A control variable for the capital city is not necessary as the data only count sub-national employment.

The Ethnic Factor

The results of my analyses, presented in Tables 1 and 2, are largely consistent with my expectations. I begin by examining how the ethnic factor influences regional distribution of public employment. In Table 1, the dependent variable is number of public employees per 1000 residents (Models 1 and 2) and total number of public employees (Model 3).Footnote 10 Following Model 2 in Table 1, TXM hired 9.28 more public employees per 1000 residents than other provinces, significant at the 99 % confidence level. To place this result in perspective, consider the case of Qinghai province, which has residents of Tibetan and Mongol descent but is a landlocked province. Qinghai had 50.12 public employees per 1000 residents. If Qinghai is a province that posed a credible instability threat (following TXM), the ratio would increase to 59.4, an 18.5 % increase over the mean value. In other words, the absolute effect of TXM is sizable. Controlling for all other factors, the provinces of TXM had almost 200,000 more public employees than other provinces. By comparison, share of minority population showed no significant effect. Consistent with my discussion in the preceding section, the results show that minority recruitment is concentrated only in regions that share borders with other countries and are credibly destabilizing.

One may question if public employment is larger in the TXM provinces not as a co-optation strategy—that is, to recruit more cadres in these areas—but as a repressive strategy. It could be possible that the added positions went toward building up local security forces. As I do not have a breakdown of public employees by departments, I included share of spending on policy and security as a proxy. Across all three models in Table 1, this variable actually posts a significant negative effect, which suggests that increased public hiring does not appear to be primarily about stepping up security forces. That said, repression and co-optation should be viewed as complementary rather than substitutive strategies. As one Xinjiang expert wrote, “The Chinese government is ready to suppress Uyghur separatism with an iron hand. At the same time, it may try to integrate the Uyghur into the PRC regime… with equal opportunity programs” (Zang 2010).

Another point to consider is whether more jobs may be assigned to Han Chinese, rather than ethnic minorities in TXM, as a strategy to “crowd-out the natives.” As my data do not specify individual characteristics of public employees, I cannot tell to whom jobs were allocated. However, available national descriptive statistics, covering an earlier period from 1951 to 1997, suggests that my results are not likely to indicate a crowd-out-the-natives story.Footnote 11 The number of minority cadres and their proportion over total public employment has steadily increased over the years. In 1980, there were about 1 million ethnic minority public employees, 5.38 % of the public force. By 1998, there were 2.74 million, with the share rising to 6.78 %. Over time, both the absolute number and proportion of ethnic minority cadres in the public workforce have grown.

The Leadership Turnover Factor

Next, I turn to the effects of leadership turnover on bureaucratic size. First, observe the impact of leadership turnover on the total number of public employees (Model 3 in Table 1), with the average value of 1.4 million personnel. Holding other factors constant, provinces that experience leadership change have 18,948 more positions than in other provinces. Then, in Table 2, I measure the dependent variable as the rate of change in public employment. On average, almost 35,000 positions were added in each province every year. Following Models 5 and 6 in Table 2, leadership turnover is associated with a steeper rate of hiring that rises over the value of the constant by 0.53 public employees per 1000 residents, or in absolute terms, 23,554 positions. For example, in 2007, Fujian province registered a growth of 36,377 bureaucratic positions, and there was no change in leadership that particular year. If there had been a change of leadership in Fujian, then 23,554 more positions are expected to be added to the cadre force. Evidently, the effects of leadership change on the absolute size and rate of increase in public employment are sizable.

There is further evidence to suggest that accelerated bureaucratic expansion associated with leadership turnover is more an indication of clientelist hiring than policy shifts among new leaders. In Table 2, I divide public employment into two main categories: administrative personnel, who are appointed in core organs, and subsidiary personnel, who work in extra-bureaucracies. Models 7 and 8 reveal that whereas leadership turnover had no significant impact on the rate of growth among administrative personnel, it significantly increased hiring among subsidiary positions by 24,446. If increased hiring was primarily explained by the policy shifts of new provincial leaders, then we should expect to see an increase among administrative personnel, as these are bureaucrats who take on planning and leadership roles in the capacity of formal civil servants. But, instead, we see that personnel expansion is concentrated in the porous extra-bureaucratic sector. As earlier discussed, extra-bureaucracies are more malleable than the core civil service as a source of clientelist hiring because of the former’s financial and hiring flexibility (Burns 2003, pp. 798–802; World Bank 2007, p. 38).

Why leadership change would bring about a seemingly large effect on the rate of public employment growth, especially in the extra-bureaucracies, deserves further consideration. Before speculating on the mechanisms, it must be emphasized that although 23,544 positions seem like a large number in absolute terms, this figure constitutes only 1.62 % of average public sector size in a province. Even in the absence of leadership turnover, Model 6 of Table 2 predicts a baseline increase of 56,570 positions in the bureaucracy over the previous year. In other words, leadership turnover accelerates an already considerable rate of bureaucratic growth. As my data do not detail at which levels or by whom appointments are made, I am unable to test the exact channels through which leadership turnover accelerates bureaucratic growth. However, the existing literature offers several clues that shed light on the substantial effects observed.

One possibility is that a new provincial leader may trigger new appointments at the next lower level, and these clients in turn bring sub-clients to office, vertically and horizontally. Patron-client chains were exposed during the recent downfall of top officials, including Bo Xilai, former provincial party secretary of Chongqing. Bo nurtured an expansive team of followers who implemented his now controversial policies (including a police chief, Wang Lijun, who executed Bo’s violent crackdown on underground gang members). Yet Bo himself was later revealed to be connected to a more senior patron—Zhou Yongkang, a former member of the Politburo standing committee and the national security czar.Footnote 12 Zhou has since been charged with corruption and sentenced to life imprisonment. According to an investigative report in Caixin, “Zhou Yongkang sat at the center of a sprawling network of subordinates, family members and business associates, many of whom have become the subject of inquiries themselves.”Footnote 13 His network reached deep into the oil and gas industries, where Zhou launched his career, and in Sichuan province, where he was appointed party secretary in 1999.

At the sub-provincial levels, a detailed case study by Hillman provides further evidence that cascading appointments follow whenever political patrons secure new offices. Describing one county, he reports, “After 6 years as district governor [the political patron] was subsequently promoted to the powerful position of Deputy Party Secretary of the Provincial Party Committee. From there he was able to continue to ensure that his network dominated politics in the district and below” (Hillman 2010, p. 6). This patron was said to have appointed protégés at the county and township levels, and across party and state organizations, subsequently yielding “a significant portfolio of positions” in the province (p. 7). In this instance, a county party secretary alone “oversaw changes to no fewer than 130 senior and middle-ranking positions” during his 3-year tenure (p. 11). In short, while it is unlikely for a new provincial leader to personally create over 20,000 positions, leadership change at the helm could trigger hiring at the lower levels.

Another explanation for the substantive effect of leadership turnover on bureaucratic growth is that in addition to hiring made by new bosses at each level, departing incumbents may create “last minute” jobs in their final year of office. At the sub-provincial level, this is a well-documented trend in the Chinese press.Footnote 14 The organization department of Zhejiang province issued a regulation forbidding city and county leaders who are leaving office from “abruptly” appointing new cadres.Footnote 15 There are two reasons why local leaders may scramble to hire before they leave. The first is that clients appointed in a former jurisdiction could one day become useful, and clients retain clientelist ties with their benefactors even if the two do not work in the same region or office. This is amply demonstrated in Zhou Yongkang’s network. Although Zhou left his position as party secretary of Sichuan province in 2003 to become the Minister of Public Security, he left behind a strong network of former aides in Sichuan who followed his bidding. After Zhou was indicted for corruption, a string of top officials in Sichuan—along with their lower-level underlings—were subsequently arrested and stripped of power. Moreover, for local leaders, appointments made on the brink of departure are virtually costless. Any fiscal consequence will be borne by their successors.

Regardless of the specific reasons that link leadership turnover to bureaucratic growth, the discussion above bears out a central irony of the Chinese political system: political elites themselves contribute inadvertently to bureaucratic expansion. For decades, the central government strove to downsize. Echoing official pronouncements about the success of downsizing campaigns, Yang claims that the central government was more successful in reforming and streamlining bureaucracy in the post-1990s than before (Yang 2004). In reality, the central government was only successful at cutting the number of departments and officially approved slots. As we can clearly see in Fig. 1, the absolute number of public employees ballooned over the years, despite repeated campaigns to trim bureaucratic flab.

Control Variables

Several interesting findings emerge from examining the control variables. There is little support for a functional explanation of public employment expansion. As we can see in Model 2 of Table 1, urbanization posts a significant positive effect on public employment size, but GDP per capita shows no significant effect. Neither variable was significant in Models 4 through 7 in Table 2. Indeed, prosperous and urbanized provinces like Jiangsu and Zhejiang have among the smallest bureaucracies in the country (see Fig. 2). The scale of public hiring also does not correspond with greater demand for public services provision. Local dependency ratio actually posts a negative and statistically significant effect on the size and growth rate of public employment (Tables 1 and 2). These results for the dependency ratio may seem contradicted by the positive effect of school enrollment rate on public hiring. However, the mean change in school enrollment is an annual reduction of 16,052 students, a consequence of China’s one-child policy. Indeed, school principals expressed worry about keeping teachers in their jobs as the student population steadily declined.Footnote 16

Summary

In short, the evidence suggests that public hiring patterns are not adequately explained by non-political factors, including the level of economic development and demand for public services. Instead, political factors are clearly more dominant. Minority-dominant provinces that pose a credible secessionist threat display a significantly higher density of public employment. Simultaneously, leadership turnover is associated with higher rates of bureaucratic expansion, specifically in the porous section of bureaucracy amendable to clientelist hiring.

The substantive effects of the ethnic and leadership factors are not strictly comparable, though it is clear that both factors contribute to bureaucratic size. TXM (Tibet, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia) is a dummy variable, and being a minority-dominant and hinterland province, according to Model 3 in Table 1, is associated with having 193,560 more administrative positions than other provinces. A new leader in office registers a smaller effect (an increment of 18,948 positions), but frequent leadership turnover over time can cumulatively account for a large number of jobs.

It is worth speculating on some conditions under which each of these factors may exert a stronger effect on public employment. The intensification of secessionist threats from the TXM provinces may lead the CCP to step up cadre recruitment in these regions. Although my data do not nearly reach back far enough, one could expect the period after the CCP crushed a revolt in Tibet and forced the Dalai Lama into exile in 1959 to be an intensive period of minority cadre recruitment in the region. On the leadership front, I anticipate that clientelist hiring may increase when the elite body is highly fragmented. That is, the larger the number of factions, the higher the rate of turnover and thus of bureaucratic growth. Testing these propositions is outside the scope of this current study. However, I hope this discussion points to some useful directions for future research.

Conclusion

Since the beginning of market liberalization, the central leadership has launched five major bureaucratic downsizing campaigns. Each time it lambasted the lower levels for bureaucratic bloat and then proceeded to slash the official number of approved positions. Yet the total size of public employment has continued to climb, rising from 19 million in 1980 to nearly 50 million by 2007. At the same time, the size of bureaucracy and pace of expansion has varied across provinces. The purpose of this article is to explore the political factors that shape the overall growth and regional distribution of public employment in authoritarian China, where usual electoral explanations fail to apply.

Bureaucratic bloat is not unique to China, but is observed throughout developing countries. Among electoral regimes, this pattern commonly results from vote buying and nascent party building. As these factors are absent in China’s single-party dictatorship, some instead view bureaucratic expansion as local governments’ defiance of central mandates to curb excessive hiring. My analysis suggests a more nuanced perspective by drawing attention to the nested structure of distributive politics in single-party dictatorships. It would be misleading to treat the “central” as a homogenous entity that is consistently unified and separate from the “local” levels. The central layer of China’s political system is itself made up of elite actors with divided goals—on the one hand, they are part of an elite circle that makes national redistributive and reform decisions; but, on the other hand, each actor is concerned with extending his or her own networks of power. As suggested in earlier literature that compares China to broker-mediated clientelist systems (Oi 1985), each patron at the helm is connected by long chains of dyadic relationships that reach down to the lowest levels of government. Hence, the paradox of bureaucratic inflation despite central commands to downsize is not simply a consequence of defiant and corrupt local agents. Rather, it is a consequence of conflicted goals among central elites and of informal vertical ties that bind political actors.

Moreover, downsizing mandates in China have not been accompanied by concrete policy and financial support from the central government. Laying off cadres en masse is politically destabilizing. Yet local leaders are evaluated on the maintenance of social stability (Zhao 2013). Incidents of mass protest can provoke dismissals. Therefore, local leaders do not seriously attempt to remove excess cadres from office, for fear of jeopardizing social stability and their own careers. Streamlining the administration also requires paying severance to those who are asked to leave their positions. However, downsizing campaigns did not come with financial support. Indeed, downsizing became yet another unfunded mandate imposed by the central government upon the lower levels. Thus, as my analysis shows, the bulk of bureaucratic expansion has not occurred in the formal civil service but rather in the subsidiary extra-bureaucracies, as the latter can earn revenue on the market to finance personnel expenditure. Indirectly, the inefficiencies and costs of bureaucratic inflation are borne by society in the form of charge-based services.

More profoundly, the repercussions of bureaucracy in China go beyond issues of size. The Chinese public and many scholarly observers view the large number of public personnel as emblematic of an ineffective and overreaching state. It is also worth noting, however, that despite the ballooning aggregate size of bureaucracy, some offices remain understaffed. My interviews suggest that while wealthy and powerful offices like the tax bureaus are amply staffed, unpopular departments like the civil affairs bureaus (which administer poverty relief) chronically lack manpower. The allocation of personnel across party-state functions underscores a normative debate about what the priorities and limits of governance ought to be in China, a debate that has gained urgency and contentiousness as societal affluence grows. As my data do not divide public employment by offices, I am unable to assess the functional distribution of jobs at this point. Instead, I have taken the first step of disaggregating public employment across provinces. Future studies may extend this line of research by unpacking employment patterns both across regions and functions.

Notes

In a separate article, I survey the available sources of data on public employment and explain why the source used here is the most comprehensive and reliable. See Ang 2012.

For instance, in standard public administrations, the official number of public employees should equate the actual size of employment. In China, however, there is a gap between state-approved and actual number of public positions. Additionally, the concept and existence of “civil servants” is relatively new in China, officially introduced after the passage of the Civil Service Law in 2006. The vast majority of China’s public administrative employees belong to an ambiguous, non-civil service category, which I term extra-bureaucracies in this article. See Ang (2012) for an elaboration of these institutional differences.

For example, Gandhi defines the dictators in communist dictatorships as the effective heads of government, specifically, “general secretaries of the communist party” (2008, p. 18). However, she acknowledges that this is not a satisfactory definition because the heads of governments in dictatorships have multiple titles and may not be effectively in charge even if they hold formal office.

The volume is titled Local Public Financial Statistics.

China implements a hierarchy-wide bianzhi system that sets an official guideline for the number of public employees in each office. In practice, the bianzhi is only a guideline; actual hiring typically exceeds bianzhi, especially if an office can generate extra funds (Ang 2012).

To give an example, the construction bureau is a state office. In a city of Jiangsu, the construction bureau supervised 18 subsidiary extra-bureaucracies, including the construction projects assessment office, construction services center, relocation and moving office, and urban science research institute (AI 2007–107).

“Repeated cycles of bureaucratic inflation,” Caijing Magazine, May 20, 2013.

A test of autocorrelation using the Wooldridge test finds serial autocorrelation in the residuals. This is expected as public employment generally increases each year, so the previous year’s values are highly correlated with the present year’s value. I correct for serial autocorrelation by adding corr(ar1) in the PCSE regression. This method is preferable to adding a lagged dependent variable to the regression, as a lagged dependent variable generates a highly inflated R2 value. As a robustness test, I ran the same analyses using lagged dependent variable instead of the corr(ar1) command, and find similar results.

China National Organizational Statistics, pp. 1348–9.

“Disgraced officials Zhou Yongkang and Bo Xilai formed ‘clique’ to challenge leaders,” South China Morning Post, January 15, 2015.

“Zhou’s Dynasty,” Caixin, 2014, accessed at http://english.caixin.com/2014/ZhouYongkang/.

See, “Hebei Qinglong district party secretary abruptly appoints 283 cadres,” Xinhua News, December 26, 2006.

See, “Zhejiang city and county party secretaries who are leaving office shall not abruptly appoint cadres,” Ningbo Net, July 9, 2010.

AI 2006–21; AI 200622

References

Ang YY. Counting cadres: a comparative view of the size of china’s public employment. China Q. 2012;211:676–696.

Ang YY. Beyond the weberian model: China’s alternative ideal-type of bureaucracy. University of Michigan, Working Paper; 2015.

Beck N, Katz JN. What to do (and not to do) with time-series cross-section data. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2006;100(4):676.

Bernstein TP, Lü X. Taxation without representation in rural China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003.

Blaydes L. Elections and distributive politics in Mubarak’s Egypt. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2010.

Bovingdon G. The Uyghurs: strangers in their own land. New York: Columbia University Press; 2010.

Bulag UE. The Mongols at China’s edge: history and the politics of national unity. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; 2002.

Burns JP. “Downsizing” the Chinese state: government retrenchment in the 1990s. China Q. 2003;175(175):775.

Calvo E, Murillo V. Who delivers? Partisan clients in the argentine electoral market. Am J Polit Sci. 2004;48(4):742.

Dickson BJ. Wealth into power: the Communist Party’s embrace of China’s private sector. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

Gandhi J. Political institutions under dictatorship. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

Geddes B. Politician’s dilemma: building state capacity in Latin America. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1994.

Gimpelson V, Treisman D. Fiscal games and public employment—a theory with evidence from Russia. World Polit. 2002;54(2):145.

Grzymala-Busse A. Rebuilding Leviathan: party competition and state exploitation in post-communist democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

Guo G. China’s local political budget cycles. Am J Polit Sci. 2009;53(3):621.

Heller PS, Tait AA. Government employment and pay: some international comparisons. Rev. and reprth ed. Washington D.C.: International Monetary Fund; 1984.

Hicken A. Clientelism. Ann Rev Polit Sci. 2011;14(1):289–310. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.031908.220508.

Hillman B. Factions and spoils: examining political behavior within the local state in China. China J. 2010;64:1.

Kerr D, Swinton LC. China, Xinjiang, and the transnational security of Central Asia. Crit Asian Stud. 2008;40(1):89.

Kitschelt H. Linkages between citizens and politicians in democratic polities. Comp Polit Stud. 2000;33(6–7):845–79.

Lande CH. Introduction: the dyadic basis of clientelism. In: Schmidt JCSSW, Landé C, Guasti L, editors. Friends, followers, and factions: a reader in political clientelism. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1977.

Landry P. Decentralized authoritarianism in China: the Communist Party’s control of local elites in the post-Mao era. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

Lazarev V, Gregory PR. The wheels of a command economy: allocating Soviet vehicles. Econ Hist Rev. 2002;55(2):324.

Lazarev V, Gregory PR. Commissars and cars: a case study in the political economy of dictatorship. J Comp Econ. 2003;31(1):1.

Lee HY. From revolutionary cadres to party technocrats in socialist China. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1991.

Li B, Walder AG. Career advancement as party patronage: sponsored mobility into the Chinese administrative elite, 1949–1996. Am J Sociol. 2001;106(5):1371.

Lü X. Cadres and corruption: the organizational involution of the Chinese Communist Party. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 2000.

Lu X, Landry P. Show me the money: interjurisdiction political competition and fiscal extraction in China. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2014;108(3):706.

Lust-Okar E. Structuring conflict in the Arab world: incumbents, opponents, and institutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Magaloni B. Voting for autocracy: hegemonic party survival and its demise in Mexico. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

Magaloni B, Kricheli R. Political order and one party rule. Ann Rev Polit Sci. 2010;13:123–43.

Magaloni B, Diaz-Cayeros A, Estevez F. Clientelism and portfolio diversification: a model of electoral investment with applications to Mexico. In: Kitschelt H, Wilkinson S, editors. Patrons, clients, and policies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

Malesky E, Schuler P. Nodding or needling: analyzing delegate responsiveness in an authoritarian parliament. Am Polit Sci Rev. 2010;104(3):482–502.

Mao Z. Telegraph on recruiting and cultivating large numbers of ethnic minority cadres (Guanyu daliang xishou peiyang shaoshu minzu ganbu de dianbao). In: Documents by Mao Zedong Following State Establishment, vol. 1. Beijing: Central Publishing Press; 1978.

Nathan AJ (1973) A factionalism model for CCP politics. China Q. 53:34–66.

O’Dwyer C. Runaway state-building: patronage politics and democratic development. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2006.

Oi J. Communism and clientelism: rural politics in China. World Polit. 1985;37(2):238.

Oi J. State and peasant in contemporary China: the political economy of village government. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1989.

Ong L. Between developmental and clientelist states: local state-business relationship in China. Comp Polit. 2012;44(2):1.

Pei M. China’s trapped transition: the limits of developmental autocracy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2006.

Robinson JA, Verdier T (2013) The political economy of clientelism. Scand. J. Econ. 115(2):260–91.

Roeder PG. Soviet federalism and ethnic mobilization. World Polit. 1991;43(2):196.

Sautman B. Preferential policies for ethnic minorities in China: the case of Xinjiang. Nationalism Ethn Polit. 1998;4(1–2):86.

Schwartz RD. Circle of protest: political ritual in the Tibetan uprising. New York: Columbia University Press; 1994.

Sheng Y. Authoritarian co-optation, the territorial dimension. Stud Comp Int Dev. 2009;44(1):71.

Shih V. Factions and finance in China: elite conflict and inflation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

Shih V, Zhang Q. Who receives subsidies? A look at the county-level in two time periods. In: Wong VSAC, editor. Paying for progress in China. London: Routledge; 2006.

Shirk SL. Competitive comrades: career incentives and student strategies in China. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1982.

Stokes S. Political clientelism. In: Stokes CBSC, editor. Handbook of comparative politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

Stokes S, Dunning T, Nazareno M, Brusco V. Brokers, voters, and clientelism: the puzzle of distributive politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

Tsai K. Capitalism without democracy: the private sector in contemporary China. Ithaca: Cornell University Press; 2007.

Tsou T. Chinese politics at the top: factionalism or informal politics? Balance-of-power politics or a game to win all? China J. 1995;34(34):95.

Wagner A (1883) Finanzwissenscaft. 3rd ed. Winter Leipzig

Walder AG. Communist neo-traditionalism: work and authority in Chinese industry. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1986.

Walder AG. The party elite and China’s trajectory of change. China Int J. 2004;2(2):189.

Wang Y, Connected autocracy (2013) APSA 2013 Annual Meeting Paper, American Political Science Association Annual Meeting.

Wank DL. The institutional process of market clientelism: Guanxi and private business in a south China city. China Q. 1996;147(147):820–38.

Wintrobe R. The political economy of dictatorship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998.

World Bank. China: public services for building the new socialist countryside. Washington D.C.: World Bank; 2007.

Yang D. Remaking the Chinese leviathan: market transition and the politics of governance in China. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 2004.

Zang X. Affirmative action, economic reforms, and Han–Uyghur variation in job attainment in the state sector in Urumchi. China Q. 2010;202:344–61. doi:10.1017/s0305741010000275.

Zhao S (2013) Rural China: poor governance in strong development. Stanford University CDDRL Working Paper No. 134.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Pierre Landry for sharing his dataset on provincial leaders, as well as Jean Oi, Andrew Walder, Alberto Diaz-Cayeros, Mary Gallagher, Anna Grzymala-Busse, Allen Hicken, Yuhua Wang, and participants at the American and Midwest Political Science Association Meetings for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ang, Y.Y. Co-optation & Clientelism: Nested Distributive Politics in China’s Single-Party Dictatorship. St Comp Int Dev 51, 235–256 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-015-9208-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-015-9208-0