Abstract

Little comparative research has examined territorially motivated co-optation under single-party authoritarianism. I argue that national autocrats in single-party regimes also have incentives to co-opt and control the more economically resourceful but potentially more politically restive subnational regions under economic decentralization and globalization to ease resource extraction and prolong their national rule. In particular, they could take advantage of their personnel monopoly power over the regional government leadership to enlarge the presence of officials governing these regions at a collective decision-making forum within the ruling party, such as its Politburo, where the national autocrats prevail. Consistent with this logic, I find, in the case of China during 1978–2005, that larger, more export-oriented, and to a lesser extent, wealthier provinces—as well as provinces with higher urbanization, centrally administered municipalities, and ethnic minority regions—were on average more likely to be governed by sitting members of the Politburo of the sole governing Chinese Communist Party Central Committees. The findings highlight a hitherto neglected territorial dimension in efforts to explain the relative resilience of authoritarian single-party regimes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is well known that leaders in authoritarian regimes seek to prolong their rule through “inclusion,” “encapsulation,” or “co-optation” of the political opposition (Jowitt 1973; O’Donnell 1973; Schmitter 1974).Footnote 1 A nascent thesis suggests that autocrats under single-party rule in particular tend to co-opt and control opposition forces from the civil society or inside the regimes (Dickson 2003; Geddes 1999). Conferring access to the perks and privileges of ruling through governing party membership could allay radical societal demands for political voice; enlarged presence at the highest decision-making organ of the ruling party for rival autocrats might mollify destabilizing intra-elite conflicts (Gandhi and Przeworski 2006).

Existing research that focuses on the state-society dichotomy or internal elite rivalry under single-party authoritarianism has neglected the territorial dimension of challenges to authoritarian rule. All else equal, subnational regions, which are better endowed with economic resources, should possess greater propensity for intransigence and pose graver potential threats to national autocratic rule under economic decentralization and globalization. If the goal of staying in office animates national authoritarian rulers as much as it does politicians elsewhere (Mayhew 1974), staving off threats from below and keeping the country together should be as vital as repelling menaces from democracy fighters in the civil society or autocratic peers in the national capital.

To the extent that single-party political institutions promote authoritarian resilience by helping co-opt and control the political opposition, national autocrats in single-party regimes could likewise seek co-optation of subnational regions that are more economically resourceful but potentially more politically restive. In particular, they could take advantage of their personnel monopoly power over the regional government leadership to enlarge the presence of officials governing these regions at a collective decision-making forum within the ruling party, such as its Politburo, where the national autocrats maintain both political and numerical preponderance.

I pursue the argument by probing the provincial-level determinants of membership for provincial officials in the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the highest decision-making body of China’s sole governing political party since 1949. I focus on the post-1978 era when economic reform and opening to the global market have economically empowered the provinces. Employing a subnational research design, I find that larger, more export-oriented, and to a lesser extent, wealthier provinces—as well as provinces with higher urbanization, centrally administered municipalities, and ethnic minority regions—were on average more likely to be governed by sitting CCP Politburo members during 1978–2005.

Political Co-optation under Single-Party Authoritarianism

Authoritarian External and Internal Co-optation

Authoritarian rulers resort to a strategy of co-optation when faced with strong opposition (Smith 2005). Credible threats to authoritarian rule arise from both outside the regime and within. Existing scholarship on authoritarian co-optation has revolved around the state–society dichotomy or internecine leadership rivalry. One view assumes that ruling autocrats are often unified among themselves. To maintain their collective grip of power, they seek to bring into the regime the vibrant but potentially unruly elements of the civil society such as the labor, intellectuals, or business entrepreneurs. Installing a nominal legislature or setting up regime-backed corporatist interest groups, for instance, often aims at pacifying previously excluded and otherwise recalcitrant societal forces (Brooker 2000).

Officially sanctioned political parties provide another tool of external co-optation for the ruling autocrats. This is particularly true in single-party regimes (Dickson 2003). Membership in the sole governing political party, rather than parties nominally permitted to exist, promises the first step to the privileges, perks, and legitimacy of ruling for those so far denied such access. Recently inducted members also infuse the party with “new blood,” and serve to expand the social support base for the regime, especially needed amid major social and economic changes (Huntington and Moore 1970).

A second line of research assumes a less monolithic authoritarian leadership. Lethal menaces to authoritarian rule lurk within the regime itself as dictators seem most vulnerable to threats from their own inner circles (Haber 2006). Regime stability requires compromises and power-sharing among powerful autocrats at the top. Compared with a military junta or a personalist dictator, authoritarian leaders under single-party rule seem more inclined to resort to such internal cooperation and co-optation for the common goal of staying in office (Brownlee 2007; Geddes 1999: 125–130). A “first institutional trench” of defense against regime collapse is to enlarge the presence of rival autocrats at a “collegial” decision-making body of the governing party, such as its Political Bureau or Politburo (Gandhi and Przeworski 2006: 17), largely absent under other types of authoritarianism. Hence, internal co-optation via single-party institutions might help mitigate intra-elite conflicts by bringing disaffected authoritarian elites into supreme leadership positions.

In short, existing scholarship has suggested that co-optation through the ruling single party could help autocrats more effectively tackle challenges to their rule from within and outside the regime. Research focusing on the state–society dichotomy or intra-elite rivalry has mostly neglected the territorial dimension of challenges to authoritarian rule, increasingly salient in the era of economic decentralization and globalization. Territorially motivated authoritarian co-optation should be at least as important as external and internal co-optation for the national autocrats in single-party regimes bent upon prolonging their rule.

Territorial Challenges to Authoritarian Rule

Claims to national rule by national autocrats presiding over more than one level of territorial administration—those effectively controlling the central government and, in single-party regimes, national leaders within the sole governing parties—as by national-level politicians everywhere, are only meaningful when the country is kept together and a central government is viable and necessary. Thus, firm political control over the entire country is prerequisite to keeping national-level authoritarian rulers in power. Located directly below the center, subnational regions could pose problems for successful national-level governance by authoritarian rulers.Footnote 2

Above all, continued rule by any government requires adequate revenue extraction (Levi 1988). Although autocrats might levy heftier taxes than democratic governments (Olson 1993), their extractive capacity is not higher (Cheibub 1998). There is some evidence suggesting that among the developing countries where autocrats are more prevalent (Przeworski et al. 2000), revenue extraction capacity is lower for authoritarian governments (Thies 2004). This could reflect the difficulty in securing citizen tax compliance when government legitimacy is low (Levi 1988), or in exacting taxation without offering political representation (Ross 2004). The challenge of financing the authoritarian state has grown especially notable along the territorial dimension in recent years.

Indeed, the twin trends of economic decentralization and globalization worldwide have not only economically empowered the subnational regions, but also increased the need for a larger fiscal role by national-level governments, democratic or authoritarian. Just as decentralization has devolved more taxing and spending powers to lower-level governments (Landry 2008; Rodden 2002), rising exposure to the global marketplace has exacerbated disparity among differentially endowed subnational regions (Hiscox 2003). Economic and political actors in subnational regions thriving in foreign trade have grown assertive in clamoring for greater local fiscal autonomy; those in regions faring less well are agitating for greater assistance (Bolton and Roland 1997).Footnote 3 In sum, economic decentralization and globalization have heightened both the need for interregional redistribution by the central governments around the world and the difficulty in extracting the requisite resources from the better-endowed regions.

As fiscal conflicts between the center and the regions brew, centrifugal pressures will mount to threaten unified national rule. While democratic governments confront similar challenges, the problem seems especially acute for national authoritarian rulers. Regional demands for greater policy autonomy or separatist tendencies might be accommodated through a peaceful, institutionalized regional vote or national referendum in democracies (Sorens 2004). Authoritarian states, unfortunately, do not have the luxury of constitutional mechanisms for mitigating center-periphery conflicts. When outright repression fails, authoritarian states are liable to violent breakups in face of rising regional economic disparity and inadequate central fiscal response, as the recent lessons of the former Yugoslavia have shown (Pleština 1992).

Territorial challenges to authoritarian national rule seem particularly worrisome if they come from the more economically resourceful regions. These regions are vital revenue bases for the central government, but they could also be potentially more politically restive. Like assertive “winner” regions elsewhere thriving in the age of economic decentralization and the global marketplace (Bolton and Roland 1997; Hiscox 2003), economically resourceful regions tend to be more resistant toward the revenue demands from national autocrats, as in the former Yugoslavia (Pleština 1992). They are also more strident in clamoring for greater fiscal or other economic policy autonomy, as in contemporary Vietnam (Malesky 2008).

In light of such challenges to the rule of national autocrats from the regions, an equally important consideration for authoritarian co-optation and control should be territorial. If single-party institutions can help promote authoritarian resilience through facilitating co-optation and control of possible internal and external opposition, can national autocrats in single-party regimes seek to prolong their rule by engaging in territorially selective co-optation and control, especially of those more economically resourceful but potentially more politically restive subnational regions?

Authoritarian Territorial Co-optation

While regional challenges from below could be disconcerting, national autocrats in single-party regimes seem well positioned to handle potential threats along the territorial dimension. In particular, leaders of authoritarian single parties often wield monopoly personnel power over the leading regional government officials, often institutionalized as the “nomenklatura” system (Harasymiw 1969; Manion 1985). Such personnel monopoly control on the subnational level, in concert with the predominance of the national autocrats at a top collective decision-making forum within the ruling party like the Politburo (see below), enables the national autocrats to engage in territorially selective co-optation through enlarging the presence at the Politburo of officials who govern the more menacing subnational regions.Footnote 4

It is common for incumbent officials working in the subnational regions to be members of the ruling Communist Party Politburo in China, Vietnam, and the former Soviet Union (Huang 2002; Lèowenhardt et al. 1992; Malesky 2008), or members of the supreme Regional Command of the ruling Baath Party in Syria (Sorenson 2008: 281). I argue that appointing ruling party Politburo members to the top offices of selected regions constitutes efforts of territorial co-optation and control by the national autocrats for three main reasons.

First, the source of their offices ensures that the presence of regional officials at the Politburo of the ruling single political party is not aimed at better representation of the interests and preferences of the actors in the subnational units that these officials govern. Absent a truly competitive electoral mechanism for regional leadership selection, top regional government officials still owe their offices to the direct appointment or nomination by the national autocrats via the sole ruling political party. Even regional officials who are Politburo members are assigned to or allowed to stay in the regional government leadership positions at the mercy of the national autocrats who wield the ultimate ruling party-imparted authority to dismiss or transfer them elsewhere. As a result, leading regional officials in authoritarian states are held accountable to their autocratic superiors above, rather than to a regional electorate below.

Second, Politburo membership for regional officials could facilitate co-optation of the regions they govern via better alignment of the incentive structure of these officials. Politburo members assigned to govern the regions should be less likely to turn into regionally based rivals for the national autocrats. A spot in the ruling party Politburo could signal that these individuals have now been accepted into the ranks of the national core leadership. This should be especially true if most of these officials posted to serve in the subnational regions will eventually return to work in the central government, as in post-1978 China (Sheng 2005: 346). For these officials, their “long-term career prospects lie with” their superiors and Politburo colleagues running the central government (Huang 1996: 197). They can be expected to internalize the latter’s more “encompassing” interests (Olson 1993) in maintaining their authoritarian national rule.

Furthermore, compared with other regional officials who are also appointed from above, Politburo members serving in the subnational regions could be better monitored by the national autocrats. Their small number (see below) and the more frequent Politburo meetings might help remedy the “information asymmetry” problem for the national leaders in a principal-agent relationship with the subnational officials (Eggertsson 1990: 33–58; Huang 2002: 69–70). For the national autocrats, having subnational officials around at the Politburo could mitigate the “noise” and other problems of ensuring accurate information flows confronting the principal (Wedeman 2001). In short, regional officials sitting in the Politburo should be more compliant with the policy preferences of the national autocrats because they have more incentives to help maintain their own national-level rule or find it harder to shirk in performing the tasks assigned by their national superiors.

Third, co-optation of the subnational regions via membership for the regional officials at a collective decision-making body of the single ruling party is also eased by the political and numerical preponderance of the national autocrats at such a forum. Territorial co-optation is not costless. Conceivably, Politburo members who serve in the subnational regions could more effectively advocate parochial regional interests on the national level. This might inordinately amplify regional political clout in the national political system. Such scenarios are not likely. Above all, the national autocrats heading the central government and the ruling single party enjoy political supremacy and are always responsible for the most important national policy-making, as in the former Soviet Union (Kramer 1999: 11) and contemporary China (Sheng 2005: 344). Because they also monopolize the personnel authority over the regional officials, as noted above (Harasymiw 1969; Manion 1985), they ultimately determine which subnational regions are governed by the Politburo members of the ruling single political party.

In addition, territorial co-optation through ruling party Politburo membership for incumbent regional officials seems exercised only sparingly and selectively. After all, national autocrats often maintain a numerical advantage at those ruling party decision-making forums lest they were overwhelmed by the regional officials at the Politburo. For instance, officials working on the Union level dominated Politburo membership shares almost through the entire existence of the former Soviet Union (1919–1990).Footnote 5 In China, central leaders occupied the overwhelming majority of CCP Politburo seats during the post-reform period of 1978–2002.Footnote 6 Moreover, only officials serving in a few regions tended to be Politburo members in the ruling single parties. In the former Soviet Union, the top leaders from the republics of Russia, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan, and the regions of Leningrad and Moscow ever made it into the Communist Party Politburo (Lèowenhardt et al. 1992: 88). As noted below, only about a third of Chinese provinces have been led by incumbent Politburo members in the recent era. Thus, territorial co-optation does not necessarily compromise the predominance of the national autocrats.Footnote 7

It is noteworthy that authoritarian territorial co-optation is distinct from internal co-optation of rival elites within the highest authoritarian leadership through power sharing and compromises at the ruling party Politburo (Gandhi and Przeworski 2006). The targets of such internal co-optation usually are individual Politburo members—disaffected rival autocrats. In contrast, the targets of territorial co-optation are the rich but restive subnational regions—including all the economic and political actors therein—that the Politburo members are assigned to govern. Territorial co-optation is also different from external co-optation of the unruly elements from outside the regime (Dickson 2003). External co-optation is pursued by directly bringing the potential opposition from the civil society into single-party membership. Yet authoritarian territorial co-optation is indirectly exercised through appointing more loyal junior colleagues of the ruling party Politburo to oversee selected subnational regions.

Meanwhile, some scholars have argued that the robustness of authoritarian co-optation is a function of potential opposition strength (Gandhi and Przeworski 2006: 10–13; Smith 2005: 430–433). More resistant toward the central government’s revenue demands and strident in clamoring for policy autonomy, more economically resourceful regions are potentially more politically restive and more likely to be subject to co-optation and control by the national autocrats. Co-opting these regions would help entice greater regional compliance with the national leaders’ policy preferences over revenue extraction. But little research has systematically examined which regions are more likely to be co-opted by the national autocrats.

Hereafter, I pursue the logic of authoritarian territorial co-optation with the case of China, for which detailed data on provincial-level economic resources and ruling-party Politburo membership for provincial officials are available. Through a subnational research design (Snyder 2001), I probe how China’s national leaders have tried to co-opt the provinces at the Politburo of the CCP Central Committees in the post-1978 era.

Authoritarian Territorial Co-optation in China

Regional Challenges to CCP National Rule

Parallel to worldwide developments of the recent decades, the major sources of challenges to CCP national rule from below have been twofold. First, economic and fiscal devolution to the provinces has strained the fiscal capacity of the central government and complicated national macroeconomic governance (Huang 1996: 63–88, 127–175; Wang Shaoguang and Hu Angang 1993). Second, China’s embrace of the global market has been accompanied by imbalanced regional growth, deteriorating economic disparity among the provinces (Kanbur and Zhang 2005), and mounting need for central redistribution. Yet even for a political system where open display of disobedience is rare, there have been signs of growing resistance to the central government and rising demands for regional policy autonomy, especially from the rich, coastal provinces (e.g., Delfs 1991; Fong 2004; Goldstein 1993; Kaye 1995; Salem 1988).

Increased resources in their own hands might have induced these provinces to “say no” to the national leaders with greater stridency. The best known example was Ye Xuanping, governor of Guangdong, who was publicly opposed to center-initiated fiscal recentralization and insisted upon continued fiscal autonomy for Guangdong in the early 1990s (Shirk 1993: 194). Another case was Shen Daren, provincial party secretary of Jiangsu, who reportedly disagreed with the then Vice Premier Zhu Rongji over the 1994 fiscal reform to centralize revenue collection (Yang 1994: 86). A popular cacophony among both academics and journalists was even predicting China’s imminent territorial disintegration (Chang 1992, 2001; Friedman 1993; Goldstone 1995; Waldron 1990).

For all the centrifugal tendencies, China’s national leaders under CCP rule so far have managed to hold the country together and remained in power (Naughton and Yang 2004). Promptly removing recalcitrant individual officials from their provincial posts was certainly the most blunt and coercive option, as they did with Ye and Shen (Shirk 1993: 189; Yang 1994: 86). One alternative for them was to ward off regional challenges to their rule through selective co-optation and control of the subnational regions. Taking advantage of their personnel monopoly power over the provincial leadership (Chan 2004; Manion 1985) and their own predominance at the Politburo of the governing CCP (Sheng 2005), China’s national leaders could manipulate the presence of the leading provincial officials at the top decision-making body of the Party and country by appointing Politburo members to govern selected provinces.

Co-optation of the Chinese Provinces at the CCP Politburo

As in other one-party states, the Politburo, composed of around two dozen members within the CCP Central Committees, is the kind of “collegial” forum in a ruling single political party (Gandhi and Przeworski 2006) responsible for the country’s major domestic and foreign policymaking (Sheng 2005: 344). It conforms well to Rigby’s apt observation of the role of the Communist Party Politburo in the former Soviet Union. The dominance of the Party over the formal state apparatus at each administrative level had relegated the Soviet central government to merely “an administrative arm of the supreme executive body of the ‘Party’, namely the Politburo” that actually governed the country (Rigby 1982: 3). Similarly, the Politburo of the CCP has ruled China since the 1949 Communist victory in the civil war.

A collective decision-making body, the Politburo is dominated by the Chinese national leaders, who head the ruling party and the central government, run the CCP national offices, and command the military. Only national leaders join an even more exclusive Standing Committee within the Politburo (Sheng 2005). The national leaders themselves boast diverse career backgrounds; some even had worked in the provinces. Nevertheless, it seems plausible to assume that these leaders, once elevated to the highest national offices of the land, are more likely to harbor policy preferences dictated by their current national leadership positions. Above all, their political survival as the supreme leaders of the country hinges on their continued grip on the national power and the success of national policies.

China’s national leaders could affect Politburo membership for the provincial officials in two ways. First, through their control of the central apparatus of the CCP, they could simply promote an incumbent provincial official into the Politburo membership. Second, they could dispatch an incumbent Politburo member to a top provincial post—the provincial party secretary, the yibashou (number one official), largely having the final say over policymaking or implementation of central policies in the provinces (Shirk 1993: Ch. 3). In either case, the personnel monopoly power over the top provincial offices is the key because even provincial officials promoted into Politburo membership can only retain their provincial offices for as long as the national leaders desire. The example of Li Changchun is illustrative. Li became a Politburo member in October 1997 while still party chief of Henan, but was transferred to Guangdong as a sitting Politburo member in February 1998. In late 2002, Li was reassigned to work on the national level.

I have argued earlier that appointing top provincial officials into the Politburo could facilitate co-optation and control of the provinces. In post-1978 China, provincial governments led by Politburo members are more apt to comply with central macroeconomic policies regarding public investment and inflation where central-provincial preferences often conflict (Huang 1996; Huang and Sheng 2008). Greater sympathy with central policy preferences could also be crucial for such purposes as revenue extraction from the provinces. But few have explicitly explored which provinces are more likely to be governed by Politburo members in the first place.

As noted above, the more economically resourceful subnational regions could also be potentially more politically restive in the age of economic decentralization and globalization. As more attractive targets for central revenue extraction, they are also more inclined to resist the revenue demands from above and to clamor for greater policy autonomy for themselves. Such intransigence aggravates centrifugal tendencies and threatens to undermine national political unity on which continued political survival of national autocrats rests. National authoritarian leaders have incentives to co-opt and control these regions to facilitate resource extraction, and keep the country together and themselves in power. Consequently, the probability that these regions are governed by members of the ruling party Politburo should be higher. Most important, regional officials who are Politburo members could be more conscientious in complying with the central revenue demands in their jurisdictions. In the case of China, I hypothesize that Politburo membership is more likely to be conferred to officials working in those provinces boasting more economic resources, other things being equal.

Data and Research Design

Politburo membership for officials working in the Chinese provinces has been far from universal. Only incumbent officials from a few of the provinces were members of the Politburo in the CCP Central Committees during 1978–2005. Why do Politburo members tend to serve in certain subnational geographic units? A casual glance at the actual provinces with Politburo members in their leadership ranks in Table 1 provides prima facie support for my hypothesis. For example, Beijing is the national capital and a major economic center in its own right. Sichuan was the country’s most populous province until 1997, when its major municipality Chongqing was carved out to become a separate provincial unit. All along, Shanghai has been China’s leading economic powerhouse.

What distinguishes the provinces from one another most in any single year seems to be whether any official from a province was present at the Politburo at all, not how much Politburo presence a province enjoyed.Footnote 8 On average, Chinese provincial officials made up only a very small percentage share of the entire Politburo membership (Sheng 2005); most of the Chinese provinces (20 out of 31) were never governed by Politburo members in this period. Therefore, it is not necessary to calculate a precise percentage share in the Politburo membership based on monthly personnel changes for each province, an approach adopted by Sheng (2005). Because national leaders can affect Politburo membership for the provincial officials through personnel changes on the provincial level in any year—for instance, by shuffling sitting Politburo members to offices in other provinces or the center. An annual measure of such changes would be more appropriate.

The unit of observation is province/year. For each province, I first draw on CCP official personnel documents to create a dummy variable that takes on a value of 1 if there were any incumbent provincial officials who were Politburo members in a calendar year. This is the dependent variable, simply called Politburo. The data start in 1978 because my main interest lies in the era to which the notions of the rise of provincial economic power are most germane and the logic of regional co-optation most pertinent.Footnote 9 They stop at the end of 2005 because of the need to lag by one year (see below) the independent variables whose data were only available up to 2004 when I started this study. There are altogether 839 observations, with a nonzero value for 99 of them. Of these, 82 observations are officials first promoted to Politburo membership in the provinces where they are observed; the remaining 17 are those transferred to the current provinces after they had become Politburo members elsewhere.

I use four variables to measure provincial economic resourcefulness, which I proxy for the attractiveness of a province as a revenue base, but also its potential political restiveness (its assertiveness in resisting central revenue demands and in agitating for policy autonomy), and its worthiness as a target for co-optation and control by the national leaders. First, many studies have suggested that under rising globalization, subnational regions benefiting from a link to the global marketplace are more likely to demand fiscal and even ultimately political autonomy (Bolton and Roland 1997; Hiscox 2003; Sorens 2004). Chinese provinces engaging in more foreign trade also tend to grow faster (Dacosta and Carroll 2001; Sun and Parikh 2001). Export, the percentage share of total provincial export in provincial gross domestic product (GDP), gauges how much a province benefits from the global market.Footnote 10

The second and third variables measure the wealth and size of a province. Level of economic wealth is measured as the natural log of provincial per capita GDP, at constant 1977 RMB—Per Capita GDP.Footnote 11 Following Su and Yang (2000: 224), I measure provincial size as the population size, the provincial percentage share of national total—Population.Footnote 12 The fourth variable, GDP Growth—the annual growth rate (in percentage) of provincial GDP at constant 1977 values—gauges provincial economic dynamism. Since I hypothesize that more economically resourceful provinces are more likely to be co-opted by national leaders, I expect the effects of the four independent variables that measure provincial exposure to the international market, wealth, size, and economic performance to be positive. Because there are other possible provincial-level factors prompting territorial co-optation by the authoritarian national rulers in China, I also control for the following three variables.

First, Bates (1981) argues that policies in developing countries are biased in favor of the urban sectors, which are more geographically concentrated and more threatening to political stability. Other scholars point to worsening political unrest in rural China in the reform era due to excessive peasant burdens fueling widespread protests (Bernstein and Lü 2000). Either more or less urbanized (i.e., more rural) provinces might pose a more credible threat to rule by the Chinese national leaders. I measure the degree of provincial urbanization with Urban Employment, the percentage share of urban employment in total provincial employment. Second, Central Municipality is a dummy variable taking on a value of 1 for the four provincial units designated as “centrally administered municipalities”—Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Chongqing (since 1997). This special administrative status might tap into their additional but unobservable political importance for the Chinese national leadership not already captured by other variables (Su and Yang 2000). Finally, I include Minority Region, a dummy variable equaling 1 for the five “autonomous regions for ethnic minorities” (Guangxi, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Tibet, and Xinjiang) perhaps more susceptible to ethnic unrest (Bovingdon 2002).

All independent and control variables are lagged by one year to mitigate mutual causality in analysis; they cover 1977–2004. The data with annual observations for 31 provinces are slightly unbalanced; Hainan and Chongqing only attained their provincial status in 1988 and 1997, respectively. There are also a few observations with missing data for Urban Employment and Export, yielding a total of 817 observations for final analysis. I use pooled cross-section time-series analysis, which allows us to examine both diachronic and spatial variation in the dependent variable with a larger number of observations.

Empirical Analysis

Cross-Section Time-Series Logistic Estimation

A dummy variable, the dependent variable essentially gauges the underlying likelihood of the provinces being ruled by sitting members of the Politburo of the CCP Central Committees during 1978–2005. Due to its binary nature, I use a logit model, the standard technique for analyzing such data in political science (Beck et al. 1998).Footnote 13 Given the time-series nature of the data, I deal with possible temporal autocorrelation in two alternative ways. First, I follow Beck et al. (1998) to add annual dummy variables for the baseline estimation. Second, I also follow Green et al. (2001) to include a lagged dependent variable to remedy serial correlation. Because of the substantive interest in the effects of such non-varying (over-time) dummy variables as Central Municipality and Minority Regions, it is not methodologically warranted to control for province-specific fixed effects here (Beck and Katz 2001).Footnote 14 The main empirical results are reported in Table 2.

Model 1 is the baseline estimation. Consistent with the hypothesis positively associating provincial economic resourcefulness with provincial Politburo membership, the coefficients for three of the four independent variables take on a positive sign. Those of Export and Population are highly significant (both at 0.01), although the coefficient for Per Capita GDP is only barely so (p = 0.154). But GDP Growth fails to attain any conventional level of statistical significance. When I replace the year dummy variables with a lagged dependent variable in model 3, Per Capita GDP also turns highly significant (at 0.05) while retaining a positive sign. Thus, there is some evidence linking provincial wealth levels and Politburo membership; yet the results for GDP Growth remain mixed and not significant. The magnitude of the coefficients for the independent variables has also diminished somehow. This result is not surprising as a lagged dependent variable tends to suppress the effects of the other independent variables (Achen 2000).

A popular theme in the overseas media and even among some academic researchers which is relevant to this period is the putative rise of the “Shanghai gang” in Chinese politics associated with the move of Jiang Zemin, former Party Secretary of Shanghai, to the national capital to assume the top post of the ruling CCP in 1989 (Harding 1997; Li 2002). Among other things, Jiang might have sought to promote into the Politburo his former associates based in Shanghai to consolidate his new power on the national level. This argument is certainly consistent with a long pedigree of scholarship treating factionalism as a staple of Chinese elite politics (Nathan 1973; Pye 1992). If Politburo membership for Shanghai reflected merely Jiang’s efforts to build a personal patron–client network, rather than the political importance of Shanghai’s economic might for the Chinese national leaders, including Shanghai in the analysis might bias the results.

In Models 2 (including annual dummy variables) and 4 (with a lagged dependent variable), I conduct additional analysis that excludes observations from Shanghai. As readily seen, the results are nearly identical to those of Models 1 and 3, respectively. If economic growth rates and levels of wealth could be affected by the ability of the provinces to export to the global market and if the interest is in the causal effect of Export, it might no longer be necessary to include GDP Growth and Per Capita GDP in the same model (King 1991: 1050). Dropping the two variables can hardly affect the results for Export in additional tests, which I did not report here for the sake of space. Thus, I decide to keep the two variables in the models because there are theoretical reasons for including them.

One way of interpreting the results of logit analysis is to examine the “first difference” effects of the independent variables. Following Tomz et al. (2003), I simulate these effects based upon the baseline Model 1 and present them in Table 3. Holding all other variables at their mean values and raising the value of Export to its maximum (about 98.8% in provincial export/GDP share for Guangdong in 2004) from its mean (around 10.11%, or that of Shandong in 1985) can increase on average the probability of provincial Politburo presence by about 0.63. Indeed, after surpassing Shanghai to become the country’s leading exporter in 1991, Guangdong has been ruled by a Politburo member since 1992.Footnote 15

Similarly, moving Population (provincial share of national total) from its mean (3.32%, Jiangxi in 1988) to its maximum (nearly 10.09%, or Sichuan in 1978) can boost the probability by as much as 0.99. Yet Sichuan lost its status as the most populous province of China in 1997, with Chongqing’s departure from its jurisdiction to become a provincial unit itself. Politburo membership for Sichuan was only temporarily replenished in 2002 before its party chief moved to work at the center in Beijing. The importance of population size per se could also have faded in more recent years. As noted, Li Chuangchun, provincial party secretary of Henan, China’s most populous province since 1997, became a Politburo member in 1997, but Li moved to Guangdong in 1998. Shandong, the third largest province but more export-oriented than is either Henan or Sichuan, replaced Sichuan in the Politburo in 1992 after the “southern tour” of Deng Xiaoping, calling for more opening to the global market, but has not been ruled by a Politburo member since late 2002. Nevertheless, for most the period, the role of provincial population size was unmistakable.

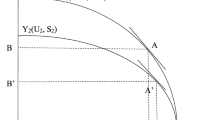

In contrast, the lack of statistical significance at the conventional levels for the coefficients of GDP Growth and Per Capita GDP in Model 1 can also be seen in their near zero or fairly flat “first difference” effects. This seems consistent with the very brief Politburo representation for provinces like Zhejiang and Jiangsu, which are rich and economically dynamic, but are neither major exporters in China nor particularly large in size. Similar patterns could also be seen in the predicted probabilities of provincial Politburo membership along different values of the independent variables, while all other independent variables are held constant, as in Fig. 1.

Predicted probabilities of provincial Politburo presence, 1978–2005. Dark solid lines refer to the predicted probabilities; light dotted lines are upper and lower 95% confidence intervals. Based on the baseline Model 1, they are plotted with CLARIFY, through holding all other independent variables (including the dummy variables Central Municipality, Minority Region, and year dummies), except for the different variables of interest, at their mean values. While the other variables are all continuous variables, the two dummy variables Central Municipality and Minority Region only take on the values of 0 and 1 in the Figure

At the same time, all three control variables—Urban Employment, Central Municipality, and Minority Region—have yielded positive and highly significant effects (at 0.01) across all specifications. In Table 3, increasing the provincial urban employment share to its maximum (79.9%, or that of Beijing in 2004) from its mean (nearly 31.9%, or that of Shanxi in 1983) can raise on average the probability of provincial Politburo membership by about 0.74. This seems to lend more support to the notion that more urbanized provinces (Bates 1981), rather than more rural (less urbanized) ones (Bernstein and Lü 2000), could be seen as more threatening to political instability in the eyes of the Chinese national autocrats and thus worthier of political co-optation through Politburo membership for their top officials.

With other factors held constant, being a Central Municipality increases the probability of provincial Politburo membership by about 0.31. It is consistent with the higher likelihood of Beijing, Shanghai, and Tianjin being ruled by a sitting Politburo member in this period, as seen in Table 1. This should not be surprising. All these places are highly urbanized and exposed to the global market to begin with. The significant effect of this variable further confirms that their additional importance is not fully captured by other variables, but perhaps helps elevate them to their special administrative status in the first place. Chongqing became such a provincial unit only in late 1997. Since late 2007, its provincial party secretary has been a Politburo member. This lies outside the time period covered here, but is consistent with an “out of sample” prediction of my models.

Finally, being a Minority Region can raise on average the probability of provincial Politburo representation by about 0.19. This relatively small effect reflects the fact that only Xinjiang, among the five ethnic minority regions, was ever ruled by Politburo members during this period. The greater potential for ethnic agitation in Xinjiang during this period could be a key factor. Xinjiang has also been the most urbanized among the five minority regions. Ethnic ferment, if combined high urbanization, might be an especially dangerous mix. Politburo membership for its provincial party secretary Seypidin Eziz (Saifuding) in 1978 before his transfer to Beijing might have been prompted by the uncertainty of the immediate post-Cultural Revolution years. Politburo membership for its party chief since 2002 followed a spate of ethnic unrest in the 1990s. More important, it also came just as China intensified its own “war on terror,” right after the militant East Turkestan Islamic Movement agitating for Xinjiang’s independence was designated by the United States State Department a terror organization linked to al Qaeda (Forney 2002).

Discussions

In sum, the empirical findings are broadly consistent with the hypothesis that Politburo membership is more likely to be conferred upon officials working in the more economically resourceful provinces in China during the post-1978 era. In particular, the results show that, all else being equal, Chinese provinces more exposed to the global market, larger in population size, and to a lesser extent with higher levels of wealth, as well as the more urbanized provinces, centrally administered metropolises and ethnic minority regions, are more likely to be co-opted by the national leaders with Politburo membership for their incumbent officials. After controlling for the level of urbanization, potential ethnic agitation, and the special administrative status of the provinces, an approach privileging provincial economic resourcefulness and its related potential political restiveness seems to be doing a good job overall in accounting for patterns of provincial presence at the Politburo of the CCP Central Committees in this era.

In this study, I am primarily concerned with understanding how national-level autocrats could seek to co-opt certain subnational regions through manipulating the presence of officials governing those regions at a single-party policymaking forum. Promotion of an incumbent provincial official into the Politburo or appointment of a sitting Politburo member to lead a certain province, I argue, aims at co-opting and controlling the province led by the official. In contrast, accounts of appointment patterns or career trajectories of specific officials might examine individual-level attributes such as personal talent, ambition, previous work performance, or factional ties to powerful patrons on the national level to explain why certain individuals rise to Politburo membership within the ruling CCP. Whereas individual-centered explanations are interesting, they do not provide as satisfactory answers to the question of why certain provinces are more likely to be governed by Politburo members.

I have tried earlier to allay concerns regarding the phenomenon of the “Shanghai gang,” whereby a top national autocrat might promote his provincial supporters to Politburo membership to consolidate his personal power against rival autocrats on the national level. Privileging the importance of possible “personal connection,” one related, but still distinct explanation could conceivably argue that Politburo members are better able to obtain the plum jobs of governing the “more comfortable” places, for instance, those larger or more exposed to the global marketplace with more opportunities for self-enrichment. Better connections with the highest national leadership could certainly be facilitated by personal socialization and ingratiating at the Politburo. This “personal connection” story might generate empirical findings that are observationally equivalent to those implied by the logic of territorial co-optation.

One obvious difficulty with this alternative logic is that it does not explain why any better-connected official would necessarily want to be assigned to an ethnic minority region with high political instability such as Xinjiang. A more serious problem is that in most cases, more than 80% of the observations with a nonzero value on the dependent variable, provincial officials were promoted into the Politburo while working in those economically resourceful provinces, even though the rest were transferred to these provinces later as sitting Politburo members. In other words, most of them did not need to take advantage of the “personal connections” made possible by Politburo membership to obtain jobs in those “coveted” provinces. They were already there in the first place, but were later brought into the Politburo, I argue, because of the possible concerns of the Chinese national leaders about ensuring greater compliance with revenue extraction and mitigating the potential political restiveness of these provinces endowed with more abundant economic resources.

Closely related to the above observation, yet another alternative explanation emphasizes the notion of a “political reward.” Also focusing on individual officials, it suggests that incumbent provincial leaders overseeing better economic performance and generating more economic resources in their jurisdictions are more likely to be promoted into Politburo membership as a reward for their talent and impressive work record. To empirically test this conjecture, I would need individual-level data on all provincial officials that bear upon their talent and work performance, a task beyond the scope of this study. Still, increasing provincial population was not an explicitly desirable national policy goal during this period under the “one child policy.” Mere economic growth does not seem to matter either for Politburo membership for provincial officials in my analysis. Of course, this logic cannot explain why officials who were already Politburo members—nearly one fifth of the observations with a nonzero value on the dependent variable—tended to be transferred to work in certain types of provinces.

Conclusion

I have argued that national autocrats in single-party regimes who preside over more than one level of territorial administration have incentives to co-opt and control the more economically resourceful but potentially more politically restive subnational regions to extract revenues, keep the country together, and maintain their own national rule. In particular, they could utilize their personnel monopoly within the ruling political party over the regional government leadership to enlarge the presence of officials governing these subnational regions at a ruling-party, decision-making forum such as the Politburo where the national autocrats maintain political and numerical supremacy.

This seems to be the case in reform-era China. Chinese national leaders have tried to appoint Politburo members of the ruling CCP to govern those more globalized, larger and, to a lesser extent, wealthier provinces, as well as those provinces that are more urbanized, centrally administered municipalities, and ethnic minority regions. This story is consistent with accounts of Beijing’s success in maintaining macroeconomic stability (Huang 1996; Huang and Sheng 2008), and in “holding China together” amid an often tumultuous economic transition (Landry 2008; Naughton and Yang 2004). But here, I have focused on the selective co-optation of the provinces by Chinese national leaders through manipulating the presence of provincial officials at the Politburo of the CCP Central Committees. During 1978–2005, the degree of provincial economic resourcefulness was a key predictor of the degree of provincial “worthiness” for political co-optation and control by national leaders in a resilient authoritarian single-party regime.

More important, the subnational-level evidence from China is consonant with a conjecture highlighting the territorial dimension of co-optation pursued by national authoritarian leaders in single-party regimes. Territorially motivated co-optation is surely not the only co-opting strategy under single-party rule to help prolong the autocrats’ tenure in office. Even in China, the CCP has sought to co-opt the more vibrant business classes into the sole governing party (Dickson 2003). More likely, national autocrats in single-party regimes simultaneously pursue internal, external, as well as territorial co-optation. But a territorial dimension has been largely missing in an extant cross-country literature that fixates on the national scene. Even case studies that probe the role of single-party institutions in promoting authoritarian internal co-optation in countries such as Egypt and Malaysia (Brownlee 2007: 122–156) rarely go beyond the national elites.

Future research should collect and examine similar subnational-level data from other countries under single-party authoritarian rule (Geddes 1999)—for instance, contemporary Vietnam under communist rule (Malesky 2008), or Mexico during the “hegemony” of Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Diaz-Cayeros 2006), where such data seem readily available. We could then further explore whether efforts by national autocrats to co-opt the more economically vital subnational regions through manipulating the presence of their leading officials at a top ruling party forum proffer a hitherto neglected mechanism behind the relative resilience of single-party regimes around the world (Brownlee 2007: 29–32; Geddes 1999: 130–138).

Research in this direction could also help us better assess whether failure to continue to exercise such regional co-optation might have led to the collapse of some erstwhile single-party regimes. For one thing, authoritarian territorial co-optation within single-party regimes depends on the effective use of the monopoly power by the national autocrats within the single party over personnel appointments on the regional level. Loosening this personnel grip over regional officials could signal the beginning of the end of their rule. This phenomenon seems to have happened in the former Soviet Union, whose disintegration resulted mostly from Gorbachev’s decision to weaken the personnel monopoly power of the Communist Party center, on which the ability of the Kremlin to exercise subnational co-optation had hinged (Filippov et al. 2004: 93–94; Solnick 1996: 229).

Notes

I use “authoritarian,” “dictatorial,” and “autocratic” synonymously to describe non democratic political systems under a personalist leader, a collective single-party leadership, or a military junta (Brooker 2000). “Co-optation,” in a dictionary definition adopted in political science, refers to efforts to “neutralize or win over ... through assimilation into an established group,” according to The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th ed. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000). Co-optation of the opposition is often pursued by ruling autocrats for purposes of political control.

By “subnational regions,” I refer broadly to the economic and political actors populating the territorial units beneath the national level and directly controlling the economic resources located in their jurisdictions. They could be the dominant economic interests (firms, sectors, etc.) and local governments dependent on them for local revenues and in their sympathy.

For a more extensive review and critique of the literature on global market integration and national disintegration, see (Sheng 2007).

National autocrats can also promote incumbent regional officials into the Politburo membership. Because the national autocrats in single-party regimes monopolize the personnel power, regional officials who are Politburo members only continue to serve in these regions at their sufferance. This is equivalent to bringing in sitting Politburo members to govern these regions.

It ranged from 59% in 1981 to 89% in 1990. Only in 1961 did officials working on the subnational and Union level enjoy equal shares (Lèowenhardt et al. 1992: 154).

On average, fewer than 13% of the Politburo members were incumbent provincial officials in any year during 1978-2002, the highest being 23.53% in 1988 (Sheng 2005: 349).

Consistent with the literature on authoritarian external co-optation of the restive elements in the civil society (Dickson 2003), the reasoning pursued here assumes that autocrats on the national level tend to act together vis-à-vis the subnational regions. However, factional strife and difficulty for “collective action” (Olson 1971) could confront most authoritarian national leaderships and constrain their ability to co-opt and control the subnational regions. But national autocrats should be more likely to act together when their common interests as national leaders are threatened from below. Even accounts that question the ability of national-level “oligarchs” in nondemocratic systems to solve their internal “collective action” problems readily admit that these leaders have little trouble unifying against their common enemies (Ramseyer and Rosenbluth 1995).

Throughout the period, most provinces with Politburo presence had only one Politburo member in any single year. The exception was Shanghai during 1978–1979, with three Politburo members—Peng Chong, Ni Zhifu, and Su Zhenghua—in its leadership ranks.

To maximize variation in the dependent variable and avoid loss of observations with nonzero values from 1978, I also include data from 1977 in later empirical analysis when a lagged dependent variable is added. This allows us to cover data from 1978.

Provincial export data are from (Guojia Tongji Ju 1999a) for 1977–1985, (China Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation 1987–2003) for 1986–2002, and (China Ministry of Commerce 2004-5) for 2003–4. I use the average annual exchange rate (the middle rate) to calculate provincial export/GDP share as provincial export data are in US dollars and GDP data are in RMB. Exchange rate data are from (Lardy 1992: 148–149) for 1977–1980, (Guojia Tongji Ju 1999b) for 1981–1984, and (Guojia Tongji Ju 2005) for 1985–2004. Unless otherwise noted, other provincial economic data are from (Guojia Tongji Ju 1999a; 2000-2005).

Provincial general retail price indices are used as GDP deflators. Price data for Tibet (1977–1989) are missing and supplanted with national averages. Hainan was part of Guangdong Province before becoming a distinct provincial-level unit in 1988, while Chongqing was part of Sichuan Province until 1997 when it was designated a provincial-level municipality under direct central administration. Data for Guangdong (before 1988) include those of Hainan while Sichuan’s data (before 1997) include those of Chongqing.

Segments of the population such as the military are not included in figures for any single province. I use the national population data from (Guojia Tongji Ju 2005), which are larger than the sum of the total from single issues of the provincial statistical yearbooks.

Due to the relatively “rare” incidence of a province being ruled by a sitting Politburo member in the sample, I have also tried logistic analysis that controls for such “rare events” (King and Zeng 2001), yielding results broadly similar to those reported here.

Including province fixed effects can also result in loss of information by dropping all observations from provinces that were never represented at the Politburo throughout this period.

One surprise is that Fujian was never ruled by a Politburo member in this period. After all, China’s post-1978 opening to the global market started in Guangdong and Fujian. But Fujian’s average export/GDP share during 1977–2004 was lower than that of Guangdong, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Liaoning. For 1992–2004, Fujian moved ahead of Liaoning, but was still behind the other three.

References

Achen CH. Why lagged dependent variables can suppress the explanatory power of other independent variables. Paper presented at Annual Meeting of the Political Methodology Section of the American Political Science Association, July 20–22, at UCLA; 2000.

Bates RH. Markets and states in tropical Africa: the political basis of agricultural policies. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1981.

Beck N, Katz JN. Throwing out the baby with the bath water: a comment on Green, Kim, and Yoon. Int Organ. 2001;55(2):487–95. (Spring).

Beck N, Katz JN, Tucker R. Taking time seriously: time-series-cross-section analysis with a binary dependent variable. Am J Polit Sci. 1998;42(4):1260–88. (October).

Bernstein TP, Lü X. Taxation without representation: peasants, the central and the local states in reform China. China Q 2000;163:742–63 (September).

Bolton P, Roland G. The breakup of nations: a political economy analysis. Q J Econ. 1997;112(4):1057–90. (November).

Bovingdon G. The not-so-silent majority: Uyghur resistance to Han rule in Xinjiang. Mod China. 2002;28(1):39–78. (January).

Brooker P. Non-democratic regimes: theory, government and politics. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 2000.

Brownlee J. Authoritarianism in an age of democratization. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

Chan HS. Cadre personnel management in China: the Nomenklatura system, 1990–1998. China Q 2004;179:703–34. (September).

Chang MH. China future: regionalism, federation, or disintegration. Stud Comp Communism. 1992;25(3):211–27. (September).

Chang GG. The coming collapse of China. 1st ed. New York: Random House; 2001.

Cheibub JA. Political regimes and the extractive capacity of governments: taxation in democracies and dictatorships. World Polit 1998;50(3):349–76. (April).

China Ministry of Commerce. Zhongguo Shangwu Nianjian. Beijing: Zhongguo shangwu chubanshe; 2004–5.

China Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation. Zhongguo Duiwai Jingji Maoyi Nianjian. Xianggang: Huarun maoyi zixun youxian gongsi; 1987–2003.

Dacosta M, Carroll W. Township and village enterprises, openness and regional economic growth in China. Post-Communist Econ. 2001;13(2):229–41. (June).

Delfs R. Saying no to Peking: centre’s hold weakened by provincial autonomy. Far East Econ Rev. 1991;151(14):21–4. (April 4).

Diaz-Cayeros A. Federalism, fiscal authority, and centralization in Latin America. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

Dickson BJ. Red capitalists in China: the party, private entrepreneurs, and prospects for political change. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003.

Eggertsson T. Economic behavior and institutions. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990.

Filippov M, Ordeshook PC, Shvetsova O. Designing federalism: a theory of self-sustainable federal institutions. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2004.

Fong L. Leadership dispute over china growth; premier Wen has heated debate with Shanghai party secretary over stringent measures to cool economy. The Strait Times (Singapore); 2004, July 10.

Forney M. Xinjiang: one nation—divided. Time (Asia Edition). 2002;159(12).

Friedman E. China’s north–south split and the forces of disintegration. Curr Hist. 1993;92(575):270–4. (September).

Gandhi J, Przeworski A. Cooperation, cooptation, and rebellion under dictatorships. Econ Polit. 2006;18(1):1–26. (March).

Geddes B. What do we know about democratization after twenty years. Annu Rev Pol Sci. 1999;2:115–44. (June).

Goldstein C. South China: resisting the centre. Far East Econ Rev. 1993;156(35):42. (September 2).

Goldstone JA. The coming Chinese collapse. Foreign Policy 1995;99:35–52. (Summer).

Green DP, Kim SY, Yoon DH. Dirty pool. Int Organ. 2001;55(2):441–68. (Spring).

Guojia Tongji Ju. Xinzhongguo Wushinian Tongji Ziliao Huibian. Beijing: Zhongguo tongji chubanshe; 1999a.

Guojia Tongji Ju. Zhongguo Tongji Nianjian 1999. Beijing: Zhongguo tongji chubanshe; 1999b.

Guojia Tongji Ju. Provincial statistical yearbooks 2000–2005 (individual issues for each province covering 1999–2004 data). Beijing: Zhongguo tongji chubanshe; 2000–2005.

Guojia Tongji Ju. Zhongguo Tongji Nianjian 2005. Beijing: Zhongguo tongji chubanshe; 2005.

Haber S. Authoritarian government. In: Weingast BR, Wittman D, editors. The Oxford handbook of political economy. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. p. 693–707.

Harasymiw B. Nomenklatura: the Soviet communist party’s leadership recruitment system. Can J Polit Sci. 1969;2(4):493–512. (December).

Harding J. Shanghai gang looking to call the shots. The Financial Times; 1997, February 22, 03.

Hiscox MJ. Political integration and disintegration in the global economy. In: Kahler M, Lake DA, editors. Governance in a global economy: political authority in transition. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2003. p. 60–86.

Huang Y. Inflation and investment controls in China: the political economy of central–local relations during the reform era. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996.

Huang Y. Managing Chinese bureaucrats: an institutional economics perspective. Polit Stud. 2002;50(1):61–79. (March).

Huang Y, Sheng Y. Political decentralization and inflation: Subnational evidence from China. Br J Polit Sci. 2008 (in press).

Huntington SP, Moore CH. Authoritarian politics in modern society: the dynamics of established one-party systems. New York: Basic Books; 1970.

Jowitt K. Inclusion and mobilization in European Leninist regimes. World Polit. 1973;28(1):69–96. (October).

Kanbur R, Zhang X. Fifty years of regional inequality in china: a journey through revolution, reform and openness. Rev Dev Econ. 2005;9(1):87–106. (February).

Kaye L. The grip slips. Far East Econ Rev. 1995;158:18–20. (May 11).

King G. ‘Truth’ is stranger than prediction, more questionable than causal inference. Am J Polit Sci. 1991;35(4):1047–53. (November).

King G, Zeng L. Logistic regression in rare events data. Polit Anal. 2001;9(2):137–63. (Spring).

Kramer M ed. Soviet deliberations during the Polish Crisis of 1980–1981, Special Working Paper No. 1, Cold War International History Project. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars; 1999.

Landry PF. Decentralized authoritarianism in China: the communist party’s control of local Elites in the post-Mao era. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

Lardy NR. Foreign trade and economic reform in China, 1978–1990. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1992.

Lèowenhardt J, Ozinga JR, van Ree E. The rise and fall of the Soviet Politburo. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 1992.

Levi M. Of rule and revenue. Berkeley: The University of California Press; 1988.

Li C. The ‘Shanghai gang’: force for stability or cause for conflict? China Leadership Monitor 2002;(2). Available at http://www.hoover.org/publications/clm/issues/2906851.html (Spring).

Malesky E. Straight ahead on red: how foreign direct investment empowers subnational leaders. J Polit 2008;70(1):97–119. (January).

Manion M. The cadre management system, post-Mao: the appointment, promotion, transfer and removal of party and state leaders. China Q 1985;102:203–33. (June).

Mayhew DR. Congress: the electoral connection. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1974.

Nathan AJ. A factionalism model for CCP politics. China Q 1973;53:33–66. (January–March).

Naughton BJ, Yang DL, editors. Holding China together: diversity and national integration in the post-Deng era. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2004.

O’Donnell GA. Modernization and bureaucratic authoritarianism: studies in South American Politics. Berkeley: Institute of International Studies; 1973.

Olson M. The logic of collective action: public goods and the theory of groups. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1971.

Olson M. Dictatorship, democracy, and development. Am Polit Sci Rev 1993;87(3):567–76. (September).

Pleština D. Regional development in communist Yugoslavia: success, failure, and consequences. Boulder: Westview; 1992.

Przeworski A, Alvarez ME, Cheibub JA, Limongi F. Democracy and development: political institutions and material well-being in the world, 1950–1990. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

Pye LW. The spirit of Chinese politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1992.

Ramseyer JM, Rosenbluth FM. The politics of oligarchy: institutional choice in imperial Japan. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995.

Rigby TH. Foreword. In The Soviet Politburo by John Lèowenhardt. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 1982. p. 1–4.

Rodden J. The dilemma of fiscal federalism: grants and fiscal performance around the world. Am J Polit Sci. 2002;46(3):670–87. (July).

Ross ML. Does taxation lead to representation. Br J Polit Sci. 2004;34(2):229–49. (April).

Salem E. Things fall apart, the centre cannot hold. Far East Econ Rev. 1988;142(43):38. (October 27).

Schmitter PC. Still the century of corporatism. Rev Polit. 1974;36(1):85–131. (January).

Shen Xueming, Zheng Jianying, editors. Zhonggong Diyijie Zhi Shiwujie Zhongyang Weiyuan. Beijing: Zhongyang wenxian chubanshe; 2001.

Sheng Y. Central–provincial relations at the CCP Central Committees: Institutions, measurement and empirical trends, 1978–2002. China Q 2005;182:338–55. (June).

Sheng Y. Global market integration and central political control: foreign trade and intergovernmental relations in China. Comp Polit Stud. 2007;40(4):405–34. (April).

Shirk SL. The political logic of economic reform in China. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1993.

Smith B. Life of the party: the origins of regime breakdown and persistence under single-party rule. World Polit. 2005;57(3):421–51. (April).

Snyder R. Scaling down: the subnational comparative method. Stud Comp Int Dev. 2001;36(1):93–110. (Spring).

Solnick SL. The breakdown of hierarchies in the Soviet Union and China: a neoinstitutional perspective. World Polit. 1996;48(2):209–38. (January).

Sorens J. Globalization, autonomy, and the politics of secession. Elect Stud. 2004;23(4):727–52. (December).

Sorenson DS. An introduction to the modern Middle East. Boulder: Westview; 2008.

Su F, Yang DL. Political institutions, provincial interests, and resource allocation in reformist China. J Contemp China. 2000;9(24):215–30. (July).

Sun H, Parikh A. Exports, inward Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and regional economic growth in China. Reg Stud. 2001;35(3):187–96. (May).

Thies CG. State building, interstate and intrastate rivalry: a study of post-colonial developing country extractive efforts, 1975–2000. Int Stud Q. 2004;48(1):53–72. (March).

Tomz M, Wittenberg J, King G. Clarify: software for interpreting and presenting statistical results (version 2.1). Available at http://gking.harvard.edu/. 2003.

Waldron A. Warlordism versus federalism: the revival of a debate. China Q 1990;121:116–28. (Mar).

Wang Shaoguang, Hu Angang. Zhongguo Guojia Nengli Baogao. Shenyang: Liaoning Renming Chubanshe; 1993.

Wedeman A. Incompetence, noise, and fear in central–local relations in China. Stud Comp Int Dev 2001;35(4):59–83. (Winter).

Yang DL. Reform and the restructuring of central–local relations. In: Goodman DSG, Segal G, editors. China deconstructs: politics, trade and regionalism. London: Routledge; 1994. p. 59–98.

Acknowledgment

Financial support from the Yale East Asian Studies Council, the Leitner Political Economy Program, and a Wayne State University 2005–2006 Research Grant are gratefully acknowledged. For helpful comments and discussions on the various aspects of the project, I want to thank Jason Brownlee, Timothy Carter, José Cheibub, Donald Green, Lei Guang, Yasheng Huang, Kevin Deegan Krause, Pierre François Landry, Edmund Malesky, Susan Rose-Ackerman, Frances Rosenbluth, Jun Saito, Lawrence Scaff, Kenneth Scheve, Yixiao Sun, David Da-hua Yang, and Dali L. Yang. I am especially indebted to the editors and reviewers of the journal for very thoughtful suggestions, and to Mr. Fred Fullerton for his excellent assistance. Any remaining errors are mine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sheng, Y. Authoritarian Co-optation, the Territorial Dimension: Provincial Political Representation in Post-Mao China. St Comp Int Dev 44, 71–93 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-008-9023-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-008-9023-y