Abstract

Background

Brain tumors represent the most common cause of cancer-related death in children. Few studies concerning the palliative phase in children with brain tumors are available.

Objectives

(i) To describe the palliative phase in children with brain tumors; (ii) to determine whether the use of palliative sedation (PS) depends on the place of death, the age of the patient, or if they received specific palliative care (PC).

Methods

Retrospective multicenter study between 2010 and 2021, including children from one month to 18 years, who had died of a brain tumor.

Results

228 patients (59.2% male) from 10 Spanish institutions were included. Median age at diagnosis was 5 years (IQR 2–9) and median age at death was 7 years (IQR 4–11). The most frequent tumors were medulloblastoma (25.4%) and diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) (24.1%). Median number of antineoplastic regimens were 2 (range 0–5 regimens). During palliative phase, 52.2% of the patients were attended by PC teams, while 47.8% were cared exclusively by pediatric oncology teams. Most common concerns included motor deficit (93.4%) and asthenia (87.5%) and communication disorders (89.8%). Most frequently prescribed supportive drugs were antiemetics (83.6%), opioids (81.6%), and dexamethasone (78.5%). PS was administered to 48.7% patients. Most of them died in the hospital (85.6%), while patients who died at home required PS less frequently (14.4%) (p = .01).

Conclusion

Children dying from CNS tumors have specific needs during palliative phase. The optimal indication of PS depended on the center experience although, in our series, it was also influenced by the place of death.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Central nervous system (CNS) tumors are the second most common pediatric cancer. In Europe, the incidence rate has been estimated to be 2.99 per 100,000 population [1]. Despite the use of multimodal therapies, the estimated 5-year mortality is 30%, making these tumors the leading cause of cancer-related death in children and adolescents [2].

Typical end-of-life symptoms include dysphagia, paralysis, headache, seizures, and cognitive impairment. This generates stress and anxiety for both patients and families and has a major impact on quality of life [3]. A greater understanding of the needs of seriously ill children and their families would enhance the quality of care offered and avoid unnecessary hospital admissions and treatments near the end of life. It would also help pediatricians, palliative care (PC) specialists, and pediatric oncologists to anticipate symptoms management and establish care goals with families. Studies on PC in children with brain tumors, however, are scarce [4,5,6,7,8].

The main aim of this study was to describe the palliative phase in children diagnosed with an incurable CNS tumor in Spain. We analyzed the characteristics of patients and PC provision, the treatment of symptoms according to tumor location, and the use of palliative anticancer treatments and palliative sedation (PS). The secondary aim was to determine whether the use of PS varied according to place of death (hospital vs. home), patient age, or involvement of a dedicated PC team.

Materials and methods

Study population and design

Multicenter retrospective, observational study of patients aged between 1 month and 18 years who died of a primary CNS tumor between January 2010 and August 2021. All Spanish hospitals with a pediatric oncology unit were invited to participate through the Spanish Society of Pediatric Onco-Hematology (SEHOP).

We considered large units those with more than 600 annual admissions and/or 70 new cases per-year (Virgen del Rocío, Vall d’Hebrón, Niño Jesús and Sant Joan de Déu). Small units were those with less than 600 annual admissions and/or 70 new cases per-year (Gregorio Marañón Hospital, Universitario de Donostia, Álvaro Cunqueiro, Virgen de la Salud, Universitario de Burgos and Montepríncipe Hospitals). We checked again and we noticed Gregorio Marañon Hospital has less than 70 new cases per year.

Regarding pediatric PC organization in Spain: in Madrid, pediatric public hospitals share a common structure and all children who require PC are attended by Niño Jesus Hospital (NJH). The only exception is Montepríncipe Hospital (from where we included seven patients), because it is private. Also, six patients from Gregorio Marañon Hospital (GMH), were not cared for in NHJ during the palliative phase, mainly due to family preferences.

Definitions

For standardization purposes, the PC phase was considered to begin when the tumor was deemed incurable (normally by the attending oncologist) and the decision made to discontinue treatment with curative intent [4, 5]. At that point, patients at hospitals with a PC unit were transferred to this unit, with the possibility of continued support from the oncology department. In other cases, PC was only provided by the oncologists. Other definitions [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] used in this study are given in Annex 1.

Data sources

A survey (Annex 2) was sent to all participants centers to be completed between November 2020 and January 2022 by a pediatric oncologist and/or PC professional. Anonymized clinical data were collected from electronic databases at the participating hospitals. The study was approved by the ethics committee at Virgen del Rocio Hospital, which waived the need for informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed to analyze if: (1) there was any difference between symptom management according to tumor location (Table 4, Annex 3), (2) palliative phase duration differed between DIPG vs non-DIPG tumors, (3) model of care during palliative phase changed according to era (2009–2013 vs 2014–2021) (Fig. 1), (4) the use of palliative sedation varied according to place of death (hospital vs. home), patient age, or involvement of a dedicated PC team vs pediatric oncology team (Annex 3).

Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS (version 28.0). Significance was set at a p level of 0.05 (two-tailed). Normally and non-normally distributed variables were compared using T test and Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis tests, respectively. Chi-square test was used for qualitative variables. Qualitative results were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies and quantitative variables as median and interquartile range (IQR).

Results

Patient characteristics

Ten out of 36 Spanish Pediatric Oncology Units agreed to participate.

We studied 228 children, 135 male (59.2%). Their characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Fourty three patients (18.85%) were treated in small hospitals and 185 (81.14%) in large hospitals. The median age was 5 years (IQR 2–9 years) at diagnosis and 7 years (IQR 4–11 years) at the time of death.

The most common tumors were medulloblastoma (n = 58, 25.4%) and diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) (n = 55, 24.1%). The most common location was the infratentorial region (n = 81, 35.5%). Patients received a median of two treatment lines (IQR 1–3, range 0–5).

Palliative care characteristics

The characteristics of PC provision are summarized in Table 2. Median duration of palliative phase was 2 months (IQR 0–7 months), and it was significantly longer in patients with DIPG (median 7 months [IQR 1–12 months], p = 0.01), compared to patients with non-DIPG tumors (median 1 month [IQR 0–5 months]).

Of the 228 children studied, 119 (52.2%) were managed by a PC team. Of these, 104 patients (87.4%) were managed by dedicated pediatric PC teams. Just under half of the patients (n = 109, 47.8%) were cared exclusively by pediatric oncology teams during palliative phase. Specialist PC provision was more common in large hospitals (105/190 patients [55.2%] vs. 14/38 patients [36.8%] at small hospitals).

Care model varied over time (Table 1, Fig. 1), with a greater proportion of patients receiving specialist PC from 2014 onwards: 26/79 (32.9%) between 2009 and 2013, 46/75 (61.3%) between 2014 and 2017, and 47/74 (63.5%) between 2018 and 2021. Differences between 2009–2013 and 2014–2021 periods were analyzed, reaching statistical significance (p = 0.03).

Overall, 157 patients (69%) died at the hospital, and 71 (31%) died at home. The main cause of death was disease progression (n = 215, 94.3%).

Clinical issues during the palliative care phase

The main symptoms reported during the palliative phase (Table 3) were motor deficits (n = 211, 93.4%) and communication disorders (n = 185, 89.8%), asthenia (n = 154, 87.5%), headache (n = 167, 83.1%), and cranial nerve impairments (n = 169, 82%).

Symptom management and use of medical devices during palliative phase

Details on the management of symptoms and use of medical devices during end-of-life care are summarized in Tables 4 and 5.

Dexamethasone was administered to 179 patients (78.5%) at a median dosage of 0.4 mg/kg/d (IQR 0.3–0.6 mg/kg/day). Median days of prescription until death was 30 days (IQR 14–68 days). Nineteen patients (8.3%) were treated with antiangiogenics (vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF] inhibitors). In total, 186 patients (81.6%) required opioids for pain control (morphine was used in 88% of the cases). Eighty-one patients (37.3%) were treated for neuropathic pain. Of these, 69% received gabapentin. Out of the 126 patients that reported pure or mixed neuropathic pain, 45 patients (35.7%) did not receive any specific treatment for this pain.

Laxatives and anti-emetics were used in 145 (64.2%) and 189 (83.6%) patients, respectively.

The most widely used medical devices were wheelchairs (n = 113, 51%) and nasogastric tubes (n = 107, 47%), particularly in the subgroup of 63 patients with a brainstem tumor (Annex 3), with respective percentages of 65% (n = 41) and 51.6% (n = 33).

Twenty-one patients (9.2%) underwent ventriculoperitoneal shunting (VPS) during the palliative phase. Median time from shunt placement to death was 2.3 months (IQR 1.4–6 months). The oncologists rated the procedure provided clinical beneficial in 59% of them (13/ 21).

When comparing symptomatic treatments between tumor locations (Annex 3), it was observed that: the use of anticonvulsants was more common in supratentorial tumors (56%, p = 0.01) and patients with medullary tumors required neuropathic pain treatment more often (75%, p = 0.012). Other differences between tumor locations were not observed.

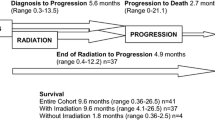

Anticancer treatment with palliative intent

Anticancer treatment with palliative intent was used in 144 patients (63%), 69 of whom (48%) received more than 1 line of treatment. The median time from last treatment to death was 43 days (IQR 15–122 days). The most common treatments were radiotherapy (n = 78, 54.26%), metronomic chemotherapy (n = 57, 39.5%), and conventional chemotherapy (n = 54, 37.5%) (Fig. 2). Targeted therapies (n = 12, 8.3%) and immunotherapy were used in 12 cases (8.3%).

Palliative sedation

In total, 111 patients (48.7%) received PS. The details are summarized in Table 5. The indication in all cases was alleviation of refractory symptoms, mainly dyspnea (n = 48, 44.6%), seizures (n = 21, 19.4%), and pain (n = 16, 14.4%).

The most widely used drug was midazolam (n = 108, 97.2%). Forty-four patients (39.6%) received morphine as an adjuvant in PS, to treat pain or dyspnea.

Most patients who received PS died in hospital (85.6%) vs. 14.4% at home (p = 0.012). No differences were observed in PS use according to patient age (p = 0.49) or care model (management by palliative care specialists vs. oncologists) (44.4% vs. 55.6%, p = 0.07).

Discussion

We studied the palliative phase in a series of 228 children from ten Spanish institutions who died of a brain tumor.

Patients experienced progressive neurologic deterioration with characteristic symptoms during the PC phase. In line with previous reports [4, 6, 7, 21,22,23], motor deficits, cranial nerve alterations, and headaches were particularly common. The percentage of patients with dyspnea, 49.3%, was similar to in other studies [7, 22].

Asthenia was also particularly prevalent (87.5%). Although asthenia is not described in other studies of pediatric brain tumors [4, 6, 7, 22], many authors believe it is one of the most common symptoms of advanced cancer in both children and adults and has the greatest impact on quality of life [22,23,24,25,26].

Dexamethasone, anti-emetics, opioids, and laxatives were the main drugs used to manage symptoms. Corticosteroids are one of the mainstays of supportive therapy in PC and neuro-oncology. Over three-quarters of patients in our series (78.5%) received dexamethasone, a rate similar to those reported elsewhere [4, 6, 7]. High doses were used (median 0.4 mg/kg/day), and median duration of treatment prior to death (30 days) was also similar to previous findings [4, 6, 7]. Some authors have claimed that low doses of dexamethasone may be as effective as high doses in certain situations [27]. Consensus, however, is lacking on optimal doses or treatment duration. The goal in all cases should be to administer the minimum effective dose in order to minimize adverse effects, which can negatively impact patient quality of life and as observed in some studies, survival [27, 28].

Antiangiogenics can be used as corticosteroid-sparing agents in children with CNS tumors. Recent studies have shown that bevacizumab in particular has significant corticosteroid-sparing effects, and it is additionally effective and well tolerated in pediatric settings, particularly in the treatment of radiation necrosis or pseudoprogression [29,30,31,32,33]. In our series, 8.3% of patients were treated with bevacizumab to alleviate edema or reduce corticosteroid dose. Certainly, 45.2% patients in our study had DIPG or HGG, which develop radionecrosis and/or pseudoprogression more frequently, and 15.3% patients received reirradiation during palliative phase (Fig. 2), which increases the risk of radionecrosis. Additionally, most of these patients were treated in large hospitals with better drug availability and less cost-related issues. Since angiogenics can improve disease/treatment-related complications of brain tumors, international guidelines are necessary to standardize indications and recommended doses, especially in pediatric PC.

The proportion of patients who received opioids for pain, 81.6%, was higher than that reported in smaller series (around 55%) [4, 6]. However, just 37.3% of patients in our series received treatment for neuropathic pain. Most of them had spinal cord tumors (Appendix 3), and pain was probably caused by direct nerve root compression [34, 35]. It is noteworthy that 45 patients (35.7%) with neuropathic pain did not receive any specific treatment for this kind of pain. While widely recognized in adults, as seen in our series, neuropathic pain tends to be underdiagnosed and undertreated in pediatric settings. A high index of suspicion, together with the use of pain scales is necessary, as it can severely impact quality of life when not properly treated [35, 36].

Anticancer treatments with palliative intent were used in more than 60% of patients, in accordance with other authors [4, 6, 7]. The median time from completion of the last treatment to death (43 days) was similar to others reported elsewhere [6, 7].

Again, supporting previous reports [4, 6, 7], chemotherapy (metronomic in 39.5% of cases and conventional in 37.5%) and radiotherapy (54.26%) were the main anticancer treatments used with palliative intent.

Only10.6% of the patients were treated with an experimental drug (targeted therapy or immunotherapy) within a clinical trial setting or under compassionate programs (this distinction was not analyzed). The difficulties associated with conducting clinical trials in pediatric patients, together with variable access to these trials across Spain’s regions [37,38,39,40], might explain why so few patients in our series were treated with novel drugs.

Of note, according to Levine et al. (n = 380), enrollment on phase I trial does not affect end-of-life care characteristics. As long as an individualized approach is used and both patients and families are involved in treatment decision-making, quality PC can be delivered regardless of clinical trial participation and should not preclude early contact with PC specialists [41, 42].

VPS was performed during the palliative phase in 9.2% patients. Risks and benefits of any invasive end-of-life procedure should be carefully weighed up and discussed with patients and families. VPS placement was perceived as beneficial by the oncologists involved in 59.1% of cases. This rate was similar to that reported in similar series that have found VPS to improve both survival and quality of life [43,44,45]. Although our observations were limited by the retrospective design of the study, the heterogeneous nature of the sample, and the lack of objective criteria for evaluating the true benefits of VPS during palliative care, this procedure could be a valid option for treating hydrocephalus in given patients, providing therapeutic relentlessness is avoided.

Median duration of palliative phase was close to 2 months, which is similar to that reported in a Dutch series of children with incurable brain tumors [7]. Of note, it was significantly longer in patients with DIPG (7 months, p = 0.01), in comparison with non-DIPG tumors. Considering the definition of palliative phase used in the present study (it was set as the point at which the patient’s illness was deemed incurable) [4, 5], patients with DIPG entered the palliative phase from the time of diagnosis, as there are no curative treatments for DIPG. However, considering that PC starts at diagnosis and continues throughout the patient’s illness [8, 9], other patients with high-risk brain tumors and poor prognostic factors in our series may have benefited from earlier initiation of this care.

Sixty-nine percent of patients in our series died in hospitals (a higher rate than that reported by other series) [4, 7, 8], indicating perhaps room for improvement in terms of accommodating patients and families wishes. The proportion of pediatric patients with life-limiting conditions who die at home varies widely according to country, type of hospital, and availability of PC resources [46,47,48]. In a multicenter study by Cantero et al. [49], only 40% of children under palliative care died at home. Noriega et al. [8], in turn, reported a rate of 64.4% in a study of 71 pediatric patients with CNS tumors at Hospital Niño Jesús in Madrid, Spain.

International guidelines, such as the NICE guideline [50], recommend that patients with advanced disease be cared for at home wherever possible due to the emotional benefits for both patients and families. PS at home is also considered safe, although it requires close monitoring by PC teams and cooperation from the family [51,52,53].

Regarding PS, 48.7% patients in our series received PS. The rates in the literature vary considerably from 65% in some series [4, 54] to 5% in others [7, 8]. Of note, not all patients with CNS tumors require PS near the end of life, as many will already be in a coma [7]. In our series, patients managed by a dedicated PC team seemed to be less likely to receive PS (44.4% vs. 55.6%, p = 0.07). Hospitalized patients were significantly more likely to receive PS than those being cared for at home (85.6% vs.14.4%). Probably, this group of patients had more complex care requirements and we did not perform a multivariate analysis to control for confounding factors. Despite this, hospitalized patients with life-limiting conditions may be more likely to receive more heavily medicalized treatment as they approach the end of life, possibly due to pressure from the family or even the medical team [48, 49]. Certainly, there is a lack of standardized protocols for pediatric PS procedures and possibly, in the present study, the optimal and time-appropriate indication of PS was mainly influenced by the team experience. A clinical guideline that can be adapted and individualized based on institutional experience and resource availability has recently been published by Cuviello et al. [54] from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Nonetheless, increased research and education on PS in pediatric neuro-oncology and standardization of clinical practice is necessary.

Strengths and limitations

This is the largest and first Spanish multicenter study that describe the palliative phase in pediatric CNS tumors. We documented all areas of PC, which provides a comprehensive view of the palliative phase in children with brain tumors and shows possible areas for improvement in their care (e.g. facilitate earlier access to PC).

Some limitations to our study need to be acknowledged. First, the criterion used to define palliative phase—judgement of incurability by the oncology team—is prone to subjectivity. Other limitations were: sample heterogeneity, use of medical records to collect data (certain symptoms may have been over-/underestimated), lack of homogeneous criteria in classifying a symptom as “irreversible” and retrospective nature of the study. We also acknowledge the study may not have country wide coverage, since most patients were treated in large centers from Seville, Madrid and Barcelona. The inequality of resources among PC teams in Spain, as well as the different dynamics in their development (some teams were probably formed during the retrospective phase of the study) were also part of the study limitations.

Certainly, there was significant heterogeneity between PC teams and possibly, many medical decisions during the palliative phase were influenced by team experience. For this reason, guidelines for good clinical practice (GPC) are necessary to standardize and improve care for children with brain tumors. With this purpose, in the near future, we plan to develop within the SEHOP group a recommendation guideline that includes algorithms for the pharmacological therapy and PC referral criteria, among others.

Conclusions

Children dying from CNS tumors face key challenges during palliative phase that require specific management. Early involvement of PC specialists should be encouraged. In our series, the use of PS was influenced by the place of death (hospital vs home), but not patient´s age or care model. GPC guidelines are necessary to improve care for children with brain tumors.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [L.M], upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- PS:

-

Palliative sedation

- PC:

-

Palliative care

- SEHOP:

-

Spanish Society of Pediatric Onco-Hematology

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- DIPG:

-

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- ITCC:

-

Innovative therapies for children with cancer

- VPS:

-

Ventriculo-peritoneal shunting

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

References

Peris-Bonet R, Martínez-García C, Lacour B, Petrovich S, Giner-Ripoll B, Navajas A, et al. Childhood central nervous system tumours—incidence and survival in Europe (1978–1997): report from Automated Childhood Cancer Information System project. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(13):2064–80.

Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, Kohler B, Jemal A. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(2):83–103.

Groh G, Feddersen B, Führer M, Borasio GD. Specialized home palliative care for adults and children: differences and similarities. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(7):803–10.

Vallero SG, Lijoi S, Bertin D, Pittana LS, Bellini S, Rossi F, et al. End-of-life care in pediatric neuro-oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(11):2004–11.

Zelcer S, Cataudella D, Cairney AE, Bannister SL. Palliative care of children with brain tumors: a parental perspective. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(3):225–30.

Kuhlen M, Hoell J, Balzer S, Borkhardt A, Janssen G. Symptoms and management of pediatric patients with incurable brain tumors in palliative home care. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2016;20(2):261–9.

Jagt-van Kampen CT, van de Wetering MD, Schouten-van Meeteren AYN. The timing, duration, and management of symptoms of children with an incurable brain tumor: a retrospective study of the palliative phase. Neuro Oncol. 2015;2(2):70–7.

de Noriega I, Martino Alba R, Herrero Velasco B, Madero López L, Lassaletta Á. Palliative care in pediatric patients with central nervous system cancer: descriptive and comparative study. Palliat Support Care. 2022;12:1–8.

OrtizSanRomán L, Martino ARJ. Enfoque paliativo en Pediatría. Pediatr Integral. 2016;XX(2):131–7.

World Health Organization. Integrating palliative care and symptom relief into paediatrics: a WHO guide for health-care planners, implementers and managers. World Health Organization. (2018). https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274561. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Accessed 10 Oct 2020.

Gómez Sancho M, Altisent Trota R, Bátiz Cantera J, Ciprés-Casasnovas L, Gándara-del-Castillo A, Herranz-Martínez JA, et al. “Atención Médica al final de la vida: conceptos y definiciones”. Grupo de trabajo “Atención médica al final de la vida”. Organización Médica Colegial (OMC) y Sociedad Española de Cuidados Paliativos (SECPAL)Gac Med Bilbao. 2015;112(4):216–18.

Rodríguez Hernández PJ, Barrau Alonso VM. Trastornos del comportamiento. Pediatr Integral. 2012;XVI(10):760–8.

Martínez MN. Trastornos depresivos en niños y adolescentes. An Pediatr Contin. 2014;12(6):294–9.

Bernaras E, Jaureguizar J, Garaigordobil M. Child and adolescent depression: a review of theories, evaluation instruments, prevention programs, and treatments. Front Psychol. 2019;10(543):1–24.

Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, Halton M, Grassi L, Johansen C, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(2):160–74.

[Internet]. World Health Organization; [Cited 9th of july 2021]. https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malnutrition. Accessed 5 Nov 2020.

Treede RD, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, Cruccu G, Dostrovsky JO, Griffin JW, et al. Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology. 2008;70(18):1630–5.

Gore M, Dukes E, Rowbotham DJ, Tai KS, Leslie D. Clinical characteristics and pain management among patients with painful peripheral neuropathic disorders in general practice settings. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(6):652–64.

Dees MK, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Dekkers WJ, Vissers KC, van Weel C. ‘Unbearable suffering’: a qualitative study on the perspectives of patients who request assistance in dying. J Med Ethics. 2011;37(12):727–34.

Voeuk A, Nekolaichuk C, Fainsinger R, Huot A. Continuous palliative sedation for existential distress? A survey of Canadian palliative care physicians’ views. J Palliat Care. 2017;32(1):26–33.

Hongo T, Watanabe C, Okada S, Inoue N, Yajima S, Fujii Y, Ohzeki T. Analysis of the circumstances at the end of life in children with cancer: symptoms, suffering and acceptance. Pediatr Int. 2003;45(1):60–4.

Goldman A, Hewitt M, Collins GS, Childs M, Hain R. Symptoms in children/young people with progressive malignant disease: United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group/Paediatric Oncology Nurses Forum survey. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):1179–86.

Portela Tejedor MA, Sanz Rubiales A, Martínez M, Centeno C. Astenia en cáncer avanzado y uso de psicoestimulantes. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2011;34(3):471–9.

Bower JE, Lamkin DM. Inflammation and cancer-related fatigue: mechanisms, contributing factors, and treatment implications. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30:48–57.

Beretta S, Polastri D, Clerici CA, Casanova M, Cefalo G, Ferrari A, et al. End of life in children with cancer: experience at the pediatric oncology department of the istituto nazionale tumori in Milan. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54(1):88–91.

Jalmsell L, Kreicbergs U, Onelöv E, Steineck G, Henter JI. Symptoms affecting children with malignancies during the last month of life: a nationwide follow-up. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1314–20.

Jessurun CAC, Hulsbergen AFC, Cho LD, Aglio LS, Nandoe Tewarie RDS, Broekman MLD. Evidence-based dexamethasone dosing in malignant brain tumors: what do we really know? J Neurooncol. 2019;144(2):249–64.

Dietrich J, Rao K, Pastorino S, Kesari S. Corticosteroids in brain cancer patients: benefits and pitfalls. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2011;4(2):233–42.

Delishaj D, Ursino S, Pasqualetti F. Bevacizumab for the treatment of radiation-induced cerebral necrosis: a systematic review of the literature. J Clin Med Res. 2017;9(4):273–80.

Baroni LV, Alderete D, Solano-Paez P, Rugilo C, Freytes C, Laughlin S, et al. Bevacizumab for pediatric radiation necrosis. Neurooncol Pract. 2020;7(4):409–14.

Barone A, Rubin JB. Opportunities and challenges for successful use of bevacizumab in pediatrics. Front Oncol. 2013;3:92.

Carceller F, Fowkes LA, Khabra K, Moreno L, Saran F, Burford A, et al. Pseudoprogression in children, adolescents and young adults with non-brainstem high grade glioma and diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. J Neurooncol. 2016;129(1):109–21.

Foster KA, Ares WJ, Pollack IF, Jakacki RI. Bevacizumab for symptomatic radiation-induced tumor enlargement in pediatric low grade gliomas. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(2):240–5.

Morgan KJ, Anghelescu DL. A review of adult and pediatric neuropathic pain assessment tools. Clin J Pain. 2017;33(9):844–52.

Walker SM. Neuropathic pain in children: steps towards improved recognition and management. EBioMedicine. 2020;62: 103124.

Moreno L, Pearson ADJ, Paoletti X, Jimenez I, Geoerger B, Kearns PR, et al. Innovative Therapies for Children with Cancer (ITCC) Consortium. Early phase clinical trials of anticancer agents in children and adolescents—an ITCC perspective. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14(8):497–507.

Quiroga Cantero E, Moreno Retortillo L, Martino AR. Ensayos clínicos y cuidados paliativos pediátricos. Med Paliat. 2019;26(2):95–6.

Benedetti DJ, Marron JM. Ethical challenges in pediatric oncology care and clinical trials. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2021;218:149–73.

Bautista F, Gallego S, Cañete A, Mora J, Díaz de Heredia C, Cruz O, et al, en nombre de la Sociedad Española de Oncología Pediátrica (SEHOP) y el Grupo de Nuevas Terapias en Oncología Pediátrica; Sociedad Española de Hematología y Oncología Pediátrica (SEHOP) and the New Drug Development Group in Pediatric Oncology. Ensayos clínicos precoces en oncología pediátrica en España: una perspectiva nacional [Early clinical trials in paediatric oncology in Spain: a nationwide perspective]. An Pediatr (Barc). 2017;87(3):155–63 (Spanish).

Levine DR, Johnson LM, Mandrell BN, Yang J, West NK, Hinds PS, Baker JN. Does phase 1 trial enrollment preclude quality end-of-life care? Phase 1 trial enrollment and end-of-life care characteristics in children with cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(9):1508–12.

Kaye EC, Jerkins J, Gushue CA, DeMarsh S, Sykes A, Lu Z, et al. Predictors of late palliative care referral in children with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;55(6):1550–6.

Schiff D, Kline C, Meltzer H, Auger J. Palliative ventriculoperitoneal shunt in a pediatric patient with recurrent metastatic medulloblastoma. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(4):391–3.

Fonseca A, Solano P, Ramaswamy V, Tabori U, Huang A, Drake JM, et al. Ventricular size determination and management of ventriculomegaly and hydrocephalus in patients with diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: an institutional experience. J Neurosurg. 2021;135(4):1139–45.

Kim HS, Park JB, Gwak HS, Kwon JW, Shin SH, Yoo H. Clinical outcome of cerebrospinal fluid shunts in patients with leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. World J Surg Oncol. 2019;17(1):59.

Bluebond-Langner M, Beecham E, Candy B, Langner R, Jones L. Preferred place of death for children and young people with life-limiting and life-threatening conditions: a systematic review of the literature and recommendations for future inquiry and policy. Palliat Med. 2013;27(8):705–13.

Levine DR, Mandrell BN, Sykes A, Pritchard M, Gibson D, Symons HJ, et al. Patients’ and parents’ needs, attitudes, and perceptions about early palliative care integration in pediatric oncology. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(9):1214–20.

Navarro-Vilarrubí S. Desarrollo de la atención paliativa, imparable en pediatría. An Pediatr (Barc). 2022;96(5):383–4.

Peláez Cantero MJ, Morales Asencio JM, NavarroMarchena L, del Velázquez González MR, Sánchez Echàniz J, Rubio Ortega L, et al. El final de vida en pacientes atendidos por equipos de cuidados paliativos pediátricos. Estudio observacional multicéntrico. An Pediatr (Barc). 2022;96(5):383–410.

Villanueva G, Murphy MS, Vickers D, Harrop E, Dworzynski K. End of life care for infants, children and young people with life limiting conditions: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2016;355: i6385.

Pousset G, Bilsen J, Cohen J, Mortier F, Deliens L. Continuous deep sedation at the end of life of children in Flanders, Belgium. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2011;41(2):449–55.

Kiman R, Wuiloud AC, Requena ML. End of life care sedation for children. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2011;5(3):285–90.

Korzeniewska-Eksterowicz A, Przysło Ł, Fendler W, Stolarska M, Młynarski W. Palliative sedation at home for terminally ill children with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2014;48(5):968–74.

Postovsky S, Moaed B, Krivoy E, Ofir R, Ben Arush MW. Practice of palliative sedation in children with brain tumors and sarcomas at the end of life. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2007;24(6):409–15.

Cuviello A, Johnson LM, Morgan KJ, Anghelescu DL, Baker JN. Palliative sedation therapy in pediatrics: an algorithm and clinical practice update. Children (Basel). 2022;9(12):1887.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MP-TL and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Ethics approval

This retrospective chart review study involving human participants was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not required since the study is retrospective, it doesn’t use identifiable private information or identifiable biospecimens and the research doesn’t involves any risk to the subjects.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Pérez-Torres Lobato, M., Navarro-Marchena, L., de Noriega, I. et al. Palliative care for children with central nervous system tumors: results of a Spanish multicenter study. Clin Transl Oncol 26, 786–795 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-023-03301-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-023-03301-7