Abstract

Neutrophilic dermatoses are a group of conditions characterized by the accumulation of neutrophils in the skin and clinically presenting with polymorphic cutaneous lesions, including pustules, bullae, abscesses, papules, nodules, plaques and ulcers. In these disorders, the possible involvement of almost any organ system has lead to coin the term ‘neutrophilic diseases’. Neutrophilic diseases have close clinicopathological similarities with the autoinflammatory diseases, which present with recurrent episodes of inflammation in the affected organs in the absence of infection, allergy and frank autoimmunity. Neutrophilic diseases may be subdivided into three main groups: (1) deep or hypodermal forms whose paradigm is pyoderma gangrenosum, (2) plaque-type or dermal forms whose prototype is Sweet’s syndrome and (3) superficial or epidermal forms among which amicrobial pustulosis of the folds may be considered the model. A forth subset of epidermal/dermal/hypodermal forms has been recently added to the classification of neutrophilic diseases due to the emerging role of the syndromic pyoderma gangrenosum variants, whose pathogenesis has shown a relevant autoinflammatory component. An increasing body of evidence supports the role of pro-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin (IL)-1-beta, IL-17 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha in the pathophysiology of neutrophilic diseases similarly to classic monogenic autoinflammatory diseases, suggesting common physiopathological mechanisms. Moreover, mutations of several genes involved in autoinflammatory diseases are likely to play a role in the pathogenesis of neutrophilic diseases, giving rise to regarding them as a spectrum of polygenic autoinflammatory conditions. In this review, we focus on clinical aspects, histopathological features and pathophysiological mechanisms of the paradigmatic forms of neutrophilic diseases, including pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet’s syndrome, amicrobial pustulosis of the folds and the main syndromic presentations of pyoderma gangrenosum. A simple approach for diagnosis and management of these disorders has also been provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The accumulation of neutrophils in the skin is the hallmark of a heterogenous group of conditions which have been named neutrophilic dermatoses [1, 2]. The cutaneous manifestations of neutrophilic dermatoses are polymorphic, including pustules, bullae, abscesses, papules, nodules, plaques and ulcers and the neutrophilic inflammation may involve almost any organ system, giving rise to the term ‘neutrophilic disease’ [2]. Neutrophilic diseases share clinical and pathological aspects with autoinflammatory diseases, which represent a spectrum of conditions characterized by recurrent episodes of inflammation in the affected organs, in the absence of infection, allergy, high titer of circulating autoantibodies or autoreactive T cells [3]. For neutrophilic diseases, a clinicopathological classification has been suggested, subdividing them into (i) deep or hypodermal forms, whose prototype is pyoderma gangrenosum; (ii) plaque-type or dermal forms, whose prototype is Sweet’s syndrome; and (iii) superficial or epidermal forms, among which amicrobial pustulosis of the folds may be considered paradigmatic. A prominent place within this group of disorders has been recently assigned to the syndromic forms of pyoderma gangrenosum whose pathogenesis has shown an important autoinflammatory component. A proposal of neutrophilic disease classification is reported in Table 1.

In this review, we focus on the paradigmatic forms of neutrophilic diseases such as pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet’s syndrome, amicrobial pustulosis of the folds and the main syndromic presentations of pyoderma gangrenosum. Clinical features and pathophysiological aspects are discussed, in the attempt to provide a simple approach for diagnosis and management.

Pyoderma Gangrenosum

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is the prototype of deep/hypodermal neutrophilic diseases. It typically presents with single or multiple skin ulcers with undermined erythematous–violaceous borders, but it may also manifest as pustular, bullous and vegetating plaque-type lesions [4, 5]. PG may be isolated or associated with different conditions, notably inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), haematological malignancies and rheumatological disorders, or it can be idiopathic [5,6,7]. It may precede, coexist or follow the different systemic diseases [8]. PG can arise as a consequence of drug therapies as well, including agents that have often been used for the treatment of the concomitant disease, particularly antagonists of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) [9,10,11]. PG may occur in the context of autoinflammatory syndromes which are discussed below [12, 13].

PG affects individuals of all ages, with a peak incidence between 20 and 50 years of age, and affects men and women almost equally [1]. However, there is a female predominance in non-malignancy-associated PG [14]. Men are more commonly affected in malignancy-associated PG and have a worse prognosis [15]. In a recent population-based study conducted in the UK, the incidence of PG was 0.63 per 100,000 per year; in the same study, PG had an incidence of 0.06 per 100,000 per year in individuals aged <10 years and an incidence of 0.26 per 100,000 per year in individuals aged between 10 and 19 years [14].

Clinical Features

Ulcerative or classic PG often starts as an inflammatory red–blue pustule a few millimetres in size, which enlarges and breaks, forming an ulceration gradually increasing both superficially and in depth. The floor of the ulceration is covered by whitish debris, necrotic tissue, purulent material or granulating tissue. The PG ulceration is overhanged by a typical well-demarcated, red-bluish or violaceous elevated undermined border, slowly progressing centrifugally in forming oval or circles arcs (Fig. 1a). The ulcers, which are typically painful, can be single or multiple and unilateral or bilateral and can range in size from a few millimetres to 30 cm or more. Their depth may be great, showing tendons, fascias and muscles [5, 16] (Fig. 1b). PG may affect all body sites, but mostly occurs on the extensor surface of the legs. Lesions start in healthy skin and may be provoked by a trauma (pathergy phenomenon). Consequently, all traumas must be avoided in PG patients. Postoperative PG may be considered as the worst consequence of the pathergy process [4, 5, 17,18,19]. Pathergy is the term used to describe hyperreactivity of the skin that occurs in response to minimal trauma not only in PG but also in other neutrophilic dermatoses, notably Sweet’s syndrome and Behçet’s disease [17]. Its precise pathogenesis is unknown, but it is regarded as due to the release of a number of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines leading to neutrophilic recruitment and activation [17]. In order to prevent pathergy phenomenon, wound debridement should be minimized and skin grafting considered only after medical therapy is initiated [19]. Peristomal PG (Fig. 1c) is caused both by the underlying IBD (ulcerative colitis or more often Crohn’s disease, rarely other causes of stomies) and pathergy on the skin-bearing appliances [20].

The speed of the ulcer extension is variable, sometimes up to 1 cm a day or more. Severe pain often accompanies lesion development, especially when rapid progression occurs. Associated symptoms may include fever, malaise, myalgias and arthralgias [4, 8]. Patients are understandingly very shocked by their lesions and need to be reassured about their healing.

PG is a chronic relapsing disease, possibly lasting for months or years if untreated. During the regression of PG, the border of the lesions collapses, redness fades and granulation tissue appears on the ulceration. In the healing stage, the wound edge has projections of epithelium extending into the ulcer, known as Gulliver’s sign. After healing, atrophic, cribriform scars persist (Fig. 1d).

In addition to the ulcerative form, a number of atypical less common variants have been described, namely the pustular, vegetative and bullous variants [5, 6, 21], which may coexist with classic PG or occur with overlapping features with other neutrophilic diseases.

Pustular PG presents with sterile pustules variable in size, number and distribution, although they most frequently occur on the trunk and extensor surfaces of limbs (Fig. 2a). They are usually surrounded by an erythematous halo. Among PG subtypes, pustular PG is most commonly associated with IBD [4, 7]. The course of these pustular eruptions often parallels that of the digestive disorder.

Perry and Winkelmann have described a bullous variant of PG in 1972 in three patients who also had leukaemia [22] and reviewed in 1992 by Ho et al. [23]. In this clinical variant of PG, bullae of variable sizes (one to several centimetres) are initially tense and their content may be clear, purulent or hemorrhagic with a cyanotic halo (Fig. 2b). Bullae rapidly transform into painful, shallow erosions and necrotic ulcers [24]. In contrast with classic PG, bullous PG is preferentially located on the upper extremities [25], including the back of the hands. Bullous PG occurs often in patients with polycythemia vera, myelodysplasia or leukaemia and in these patients is indicative of a poor prognosis [26]. Many cases, however, are observed in the absence of a concurrent disorder.

Even if granulomas have been described in late classic PG [27], they are typical for vegetative PG, which is considered as a distinct variant [28]. Vegetative subtype presents as an isolated and superficial ulceration variable in size from one to several centimetres without purulent base, undermined borders or surrounding erythema, which gradually transform into an erythematous exophytic lesion [29, 30]. This appears as an infiltrated plaque with a vegetative or verrucous surface (Fig. 2c). The loss of substance is minimal, and borders are only slightly elevated, nor purulent nor violaceous. Vegetative PG is the most uncommon and benign subtype and is least frequently associated with underlying systemic disorders. Non-aggressive treatment is often effective [1]. The preferential location is the trunk, but the legs and other areas are also affected.

Systemic involvement of PG is rare except for joint manifestations which are common and include several patterns ranging from monoarthritis to destructive polyarthritis; the synovial fluid contains neutrophils and is invariably sterile [2]. Lung involvement is probably underreported because the respiratory manifestations are non-specific, including cough, dyspnoea and thoracic pain, sometimes accompanied by fever. Interstitial infiltrates or condensations are visible on radiograph, and bronchoalveolar lavage shows neutrophils and no bacteria [2, 31]. Primary PG of the lung preceding cutaneous PG has been described in two patients [31, 32]. There are scattered reports of liver, kidney and meninges involvement [2, 33].

In a rather unique situation among cutaneous diseases, there are no histopathological, biological or other absolute criteria for the diagnosis of PG. Two different groups [21, 34] proposed similar diagnostic criteria which are reported in Table 2.

Few cases are directly lethal, but PG patients have an increased risk of death [14, 20, 35, 36]. Fatal outcome may result from the associated disease, visceral complication or localization [14] infectious events or iatrogenic complications [37]. In a recent review, the mortality rate was found to be 16% during an 8-year study period [36] while in the study of Langan et al. [14], the risk of death was three times higher than that for general controls.

Histopathological Aspects and Laboratory Findings

The histopathological features of PG, albeit non-specific, are helpful in ruling out other causes of ulceration. The time and site of the biopsy must be carefully selected. It is recommended to take an elliptic specimen including the margin and the floor of the ulcer.

On a large and deep enough biopsy, the dermis and the subcutaneous fat are massively infiltrated by a suppurative inflammation that contains neutrophils, haemorrhages and necrosis [4,5,6]. The infiltrate destroys preexisting structures, follicular units and adnexal glands. Vessels can be necrotic with thrombosis, these alterations being secondary to the neutrophilic inflammation (Fig. 2d). All these features are in favour of classic PG after exclusion of an infection.

If the biopsy is made too early in the lesion course and on the peripheral extension area, there is a perivascular and/or perifollicular infiltrate predominantly composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes. This histologic aspect is quite non-specific and does not contribute to the diagnosis.

In pustular PG and in initial pustules of ulcerative PG, the infiltrate has a tropism for the hair follicles. The infundibulum shows signs of rupture or perforation and contains and/or is surrounded by a dense neutrophilic infiltrate.

In bullous PG, lesions are characterized by subepidermal and intraepidermal collections of neutrophils. Immunofluorescence is negative or non-specific.

In vegetating PG and also in some cases of classic PG, neutrophils are associated with epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells which form granulomas.

In all cases, special histochemical stains for fungi and mycobacteria as well as cultures for microbiological identification are negative; this information is of paramount diagnostic relevance.

Laboratory tests are performed to evaluate for associated disorders rather than to establish a diagnosis of PG. In a recent study on a large series of PG patients [14], disease associations are reported in approximately one third of cases, including IBDs (20.2%), rheumatoid arthritis (11.8%) and haematological disorders (3.9%).

Sweet’s Syndrome

Originally described by Robert Douglas Sweet in 1964 [38], Sweet’s syndrome (SS), the eponym for acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is an uncommon inflammatory skin disease characterized by fever; neutrophilia (with blood polymorphonuclear leukocyte level greater than 10,000/mm3); painful, erythematous 0.5- to 12-cm papules or plaques on the extremities, face and neck; and a dense neutrophilic infiltrate in the papillary dermis [21, 39, 40]. Additional criteria for SS include absence of infection and responsiveness to corticosteroid [6, 41]. The diagnostic criteria for SS are reported in Table 3.

SS can be classified into classic, malignancy-associated and drug-induced SS, depending on the clinical setting in which the disease develops.

The distribution of Sweet’s syndrome cases is worldwide, and there is no racial predilection [40]. To the best of our knowledge, no population-based studies have been conducted to evaluate SS incidence; however, in our experience, SS incidence is about five times lower than that of PG. Classical or idiopathic SS predominantly affects female subjects. It may be associated with infections (upper respiratory tract or gastrointestinal tract), IBD or pregnancy [42]. Recurrence of the dermatosis is noted in approximately one third of individuals. The most frequently associated conditions are reported in Table 4, including in particular haematologic malignancies (19%), solid tumours (23%) and drug exposure (27%). The sporadic form occurs in 31% of cases while the other forms are described only in scattered reports [40].

The initial episode of classical SS most frequently occurs between the ages of 30 and 60 years, but it has been reported also in children and younger adults [43].

Clinical Features

Classic or idiopathic SS is characterized by the abrupt onset of tender, elevated, sharply limited, intensely red papules or coalescent plaques, variable in size from 1 to several centimetres. Some of these plaques may be annular (Fig. 3a), but usually, they have no identifiable shape, and the comparison with an irregular mountain range profile is the best description [5]. There is pronounced oedema, and some lesions may have a transparent, vesicle-like appearance. In some instances, the bullous component is prominent, with clear or haemorrhagic blisters leading to superficial ulcerations. SS can appear as a pustular dermatosis too, characterized by either erythematous-based pustules or tiny pustules on the tops of red papules [44]. Targetoid lesions mimicking erythema multiforme can also be seen (Fig. 3b). Subcutaneous SS (Fig. 3c) is characterized by skin lesions which usually present as erythematous, tender dermal nodules on the extremities, which may mimic erythema nodosum when they are located on the legs [45, 46].

The eruption is often distributed asymmetrically. It presents as either a single lesion or multiple lesions variable in size. They predominate on the face, neck, upper trunk and upper limbs, but may occur anywhere. Mucosal lesions are exceptional. SS lesions, either spontaneously or after treatment, usually resolve without scarring. The rapid resolution of symptoms following corticosteroid therapy is a clue feature of SS.

Patients may present with prodromal symptoms such as fever, malaise or arthralgia. A prior upper respiratory tract infection is frequently associated with SS. The cutaneous manifestations can also present concurrently with fever, arthralgia and generalized malaise. Headache and a frequent episcleritis are considered part of the inflammatory syndrome.

Extracutaneous neutrophilic involvement may be seen in almost any organ systems, particularly joints (clinically manifesting as monoarthritis to destructive polyarthritis), lung (cough, dyspnoea and thoracic pain), kidney (generally nephrotic syndrome) and central nervous system (altered state of consciousness, headache, generalized seizures, memory disturbances and paresis) [2, 31, 47,48,49,50]. The occurrence of visceral SS, as well as non-cutaneous PG, represents one of the bases of the current conception of the neutrophilic disease. As is also the case for PG, visceral SS localizations may, rarely, be fatal [51, 52].

Numerous retrospective reviews and case reports have supported a strong association between SS and malignancies [5, 6]. In particular, SS is recognized to be associated with leukaemia, mainly acute myelogenous leukaemia, and may in some instances reveal the blood malignancy or a relapse. More rarely, other blood or solid cancers, especially genitourinary tumours, have been reported in association with SS. Paraneoplastic SS occurs as frequently in men as in women, and it is less often preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection. In addition, in malignancy-associated SS, lesions are more widespread, mucosal involvement is more common, blood neutrophilia is inconstant, and there is often an associated anaemia and/or thrombocytopenia.

Another clinical setting that can be encountered when evaluating patients with SS is the onset of the disease caused by the use of medications. Numerous case reports have been published, and criteria for drug-induced SS have been proposed [53]. Causality is probable for granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and all-trans retinoic acid, which are directly involved in the pathogenesis of SS. The evidence implicating vaccines and minocycline is also convincing [54, 55]. Many other drugs have been implicated in reports considered as anecdotal. A temporal relationship between drug ingestion and clinical presentations of SS should be established to classify a patient as having drug-induced SS [53].

An association with inflammatory diseases, such as IBD, Behçet’s disease, relapsing polychondritis, rheumatoid arthritis and thyroid disease, and with infectious diseases has also been reported in many isolated case reports, but the significance of these associations is unclear [36].

The bones, central nervous system, ears, eyes, kidneys, intestines, liver, heart, lung, mouth, muscles and spleen can be the sites of extracutaneous manifestations of SS [51,52,53]. Ocular manifestations may be the presenting feature of SS.

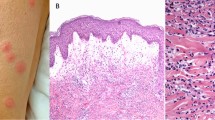

Histopathological Aspects and Laboratory Findings

Histopathological examination reveals an infiltrate consisting predominantly of mature neutrophils typically located in the upper dermis, without evidence of vasculitis (Fig. 3d). An oedema of the papillary dermis is frequent, sometimes resulting in subepidermal vesiculation. The neutrophilic infiltrate may extend into the subcutaneous tissue with septal and/or lobular involvement [38, 40, 46]. Other typical histologic features may include a mixture of lymphocytes and eosinophils, vascular endothelial swelling and erythrocyte extravasation.

Leukocytosis as well as an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate is the predominant laboratory finding [41].

Amicrobial Pustulosis of the Folds

Amicrobial (or aseptic) pustulosis of the skin folds (APF) is a rare neutrophilic dermatosis, occurring almost exclusively in young women with varying underlying autoimmune or dysimmune diseases [56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. It is characterized by relapsing sterile pustular eruptions mainly involving the skin folds. The disease was first reported in 1991 by Crickx and colleagues [63], who described two young women with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and outbreaks of amicrobial pustules involving the scalp, major folds and external ear canals. Subsequently, two other similar cases have been described in association with SLE and incomplete SLE, respectively [64, 65], and three additional cases in young women with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), celiac disease and various non-specific serum autoantibodies [56]. It has been emphasized that this form may be associated not only with lupus, but also with a broad spectrum of underlying autoimmune diseases or immunological abnormalities [56]. Since then, similar clinical features have been described in association with a number of other autoimmune disorders [57,58,59,60,61,62, 66,67,68]. Recently, APF has been included within the spectrum of autoinflammatory diseases on the basis of pathophysiological findings and clinical evidences of its association with conditions like IBD [69, 70]. Paediatric patients have been described only in a single case series recently studied by our group [69].

Clinical Features

APF is characterized by sudden onset of follicular and non-follicular sterile pustular lesions involving the main cutaneous folds, usually with symmetrical distribution, anogenital area and scalp (Fig. 4a, b) as well as the minor skin folds, particularly the area around the nostrils, retroauricular regions and external auditory canals. Generalized forms of pustulosis may be rarely observed [61]. The pustules overly erythematous, eczematous or macerated skin surfaces, may tend to coalesce forming oozing, crusted or erosive areas and are usually accompanied by burning or pain. Onychodystrophy with suppurative vegetating paronychia is a common finding [61]. Although APF is typically amicrobial in origin, various bacterial species may secondarily colonize older pustular lesions and macerated erosive areas. Relapses of APF following tapering or discontinuation of treatment are common whereas long-term remissions of the disease have been only rarely reported [60].

The diagnosis of APF is challenging, as it shares clinical and histological features with other pustular disorders. In fact, the clinical picture of APF is similar to that of primary infectious subcorneal pustules, pustular psoriasis, mainly its inverse type, which, however, usually spares the minor folds and often presents with psoriasis lesions in other sites of the body. APF must also be differentiated from a number of other conditions, including subcorneal pustular dermatosis or Sneddon–Wilkinson disease, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and autoimmune bullous diseases with pustular or erythematous presentation such as pemphigus foliaceus and IgA pemphigus, respectively.

Marzano et al. [61] have proposed a set of criteria for assisting with differential diagnosis of APF (Table 5). In particular, obligate features include the occurrence of pustules along either one major or minor flexure and the anogenital area, intraepidermal pustules with a dermal mainly neutrophilic infiltrate on histology and negative microbial cultures from unopened pustule. Minor criteria include autoimmune comorbidities and anti-nuclear antibody titers of at least 1/160 or positivity in a number of circulating autoantibodies, particularly anti-extractable nuclear antigen (ENA), anti-dsDNA, anti-smooth muscle, anti-mitochondrial, anti-parietal cell or anti-endomysium. The authors suggested that diagnosis of APF can be ascertained if all the obligate criteria and at least one minor criterion are fulfilled. At present, this algorithm is under validation. APF usually occurs in patients affected with autoimmune/dysimmune or autoinflammatory diseases, mostly SLE. Numerous other underlying diseases have been reported, including SCLE, SLE/scleroderma overlap syndrome [69], mixed connective tissue disease [66, 71], myasthenia gravis [57], Sjögren syndrome [59, 72], celiac disease [56], rheumatoid arthritis [73], idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) [57], immunoglobulin A nephropathy [72], Hashimoto’s thyroiditis [74] and autoimmune hepatitis [62]. The course of APF not always parallels that of the associated condition, and albeit less commonly, a sporadic form can also be seen [69].

Skin reactions manifesting as APF developed after treatment with anti-TNF agents, namely infliximab and adalimumab given for IBD, have been reported in the literature [70, 75]. The observation of these paradoxical reactions following anti-TNF therapy for IBD expanded both the clinical context during which APF may occur and the spectrum of cutaneous complications related to anti-TNF biologics.

Histopathological Aspects and Laboratory Findings

The histopathological findings include subcorneal or intraepidermal spongiform pustules and a dermal inflammatory infiltrate predominantly consisting of neutrophils, without vasculitis [56, 61, 76]. Older plaques may show psoriasiform hyperplasia with parakeratosis, neutrophil exocytosis and a dermal lymphocytic infiltrate (Fig. 4c). Direct and indirect immunofluorescence is characteristically negative.

An increase in the acute phase reactants, namely erythrocyte sedimentation rate and serum levels of C reactive protein, is a common finding in APF patients. Various serum autoantibodies are frequently detected. However, since autoantibodies can be found in patients’ serum regardless of the presence of an underlying autoimmune/dysimmune disease [69], autoantibodies seem to not necessarily have a clinical relevance.

Syndromic Forms of Pyoderma Gangrenosum

PG may occur in the context of rare, genetic autoinflammatory syndromes such as PAPA (pyogenic arthritis, PG and acne), PASH (PG, acne and suppurative hidradenitis) or PAPASH (pyogenic arthritis, acne, PG and suppurative hidradenitis) [12, 13].

Pyogenic Arthritis, Pyoderma Gangrenosum and Acne Syndrome

PAPA syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant disease that is characterized by aseptic inflammation of the skin and joints, particularly the elbows, knees and ankles [77]. In particular, the acronym ‘PAPA’ embraces the unusual clinical symptom triad of pyogenic sterile arthritis, PG and acne. Painful, recurrent, sterile monoarticular arthritis with a prominent neutrophilic infiltrate usually occurs in childhood and may be the presenting sign of this condition [78]. Persistent disease can cause joint erosions and destruction, although joint symptoms tend to decrease and skin symptoms become more prominent in young adults.

Skin involvement varies. Pathergy is frequent, and formation of pustules with subsequent ulceration may be induced early in life upon minimal trauma. Severe nodulocystic acne and PG tend to develop around puberty and may persist into adulthood [79]. In the context of PAPA syndrome, PG has a clinicopathological aspect that is closely similar to that of the classical presentation of its isolated form [20].

Acne is a clinically polymorphic inflammatory disease affecting the pilosebaceous units, which consists of open comedones (blackheads), closed comedones (whiteheads) and inflammatory lesions such as papules, pustules and nodules. Its complex pathophysiology includes disordered keratinisation with abnormal sebaceous stem cell differentiation. An autoinflammatory component induced by Propionibacterium acnes via inflammasome activation has recently been demonstrated [80,81,82]. Other dermatological manifestations described in the setting of PAPA include psoriasis and rosacea.

Standard laboratory findings reflect systemic inflammation with leukocytosis and high levels of acute phase reactants, but are otherwise non-diagnostic. Genetic analysis allows to identify the presence of mutations involving the proline–serine–threonine–phosphatase interactive protein 1 (PSTPIP1) gene [78].

Pyoderma Gangrenosum, Acne and Suppurative Hidradenitis

The clinical triad of PASH (PG, acne and suppurative hidradenitis) is an autoinflammatory syndrome [83, 84] that can be distinguished from PAPA by the absence of pyogenic sterile arthritis. Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), also known as suppurative hidradenitis or acne inversa, is a neutrophilic dermatosis, which is itself currently considered autoinflammatory in origin, like PG [85,86,87]. HS is a chronic relapsing, debilitating inflammatory disease of the hair follicle that usually presents after puberty, affecting apocrine gland-bearing skin, most commonly the axillae, inguinal and anogenital regions [88]. It is clinically characterized by recurrent, painful, deep-seated nodules commonly ending in abscesses and sinus tracts with suppuration and hypertrophic scarring [88,89,90].

The subjects affected by PASH so far described in the literature are young adults with a very early onset of the syndrome’s clinical features, especially acne, usually occurring at puberty [83, 84, 91, 92]. Three patterns of skin lesions have been described: (i) ulcers and ulcerated nodules, sometimes with the vegetating aspects typical of PG; (ii) papulo-pustular lesions, abscesses and fistulae evolving into draining sinuses and scars that are consistent with HS; and (iii) mild to severe facial acne, including acne fulminans (Fig. 5). Concurrent rheumatological symptoms and IBD have also been described [84].

Patients with PASH syndrome have a significantly impaired quality of life due to the extensive skin involvement, the chronicity of the cutaneous manifestations, their disfiguring sequelae and the limited available treatment options.

Other Syndromic Forms

In 2012, Bruzzese reported the case of a patient with the simultaneous presence of PG, acne conglobata, HS and axial spondyloarthritis, a condition that differed from PASH (in which arthritis is absent), and PAPA syndrome (in which HS is absent). The author suggested that the simultaneous development of these four pictures may represent a distinct syndrome, which he named PASS syndrome [93]; to date, no genetic defect has been identified.

Two other research teams independently described two new entities among the autoinflammatory syndromes, both of which were named PAPASH syndrome [94, 95]. Marzano et al. described the case of a 16-year-old female with pyogenic arthritis, PG, acne and HS [94]. On the other hand, Garzorz et al. proposed using the same acronym PAPASH to define the association of PG, acne, psoriasis, arthritis and HS observed in a 39-year-old woman [95]. Finally, it has been suggested that the concomitant diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (PsA), PG, acne and HS described in a 50-year-old man represents a new syndrome known as PsAPASH [96].

Pathophysiology and Genetics of Neutrophilic Diseases: the Model of Autoinflammation

An increasing body of evidence supports the role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the pathophysiology of neutrophilic dermatoses. It is noteworthy that neutrophilic dermatoses share the same pro-inflammatory effectors also found in autoinflammatory syndromes, suggesting common physiopathological mechanisms [6, 12]. In particular, both autoinflammatory syndromes and neutrophilic dermatoses are characterized by an overactivated innate immune system leading to the increased production of the interleukin (IL)-1 family and ‘sterile’ neutrophil-rich cutaneous inflammation. Therefore, both can be considered ‘innate immune disorders’ [12, 97]. Recently, identification of additional amplification loops of type I interferons and the innate pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-18 and IL-36, as well as the successful use of targeted anti-IL-1 therapies in a variety of diseases, has led to an extension of the concept of autoinflammation [98].

The term ‘autoinflammatory syndrome’ was initially introduced after the identification of the genetic causes of the most prevalent monogenic autoinflammatory disease worldwide—the autosomal recessive disease familial Mediterranean fever—and the discovery of TNF receptor mutations in the autosomal dominant disorder, TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome, in 1999 [99]. Since then, the number of identified autoinflammatory diseases has increased considerably. Several mutations associated with autoinflammatory disorders occur in the IL-1β pathway [100]. Indeed, various mutations have been described in genes encoding signalling molecules, including germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors, which are involved in triggering innate immune responses [101]. Gain-of-function mutations in the nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich repeat-containing receptor protein 3 gene (NLRP3) have been recognized as an aetiological factor of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS), which typically present with neutrophil-rich urticarial skin lesions [102]. These NLRP3 mutations result in overproduction of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β due to the activation of a cytoplasmic innate immune protein complex called inflammasome. The inflammasome is a molecular platform which promotes the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [103]. Inflammasome activation begins with the presence of the molecules associated with cell damage [damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs)] or pathogen infections (pathogen-associated molecular patterns [PAMPs]) in the extracellular environment. These are recognized by specific receptors [104] such as NLRP3, leading to the subsequent assembly and activation of the inflammasome composed of NLRP3, ASC [apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain (CARD)] and caspase-1. Activated caspase-1 can cleave pro-IL-1-β and the pro-inflammatory cytokine pro-IL-18 to their active forms. IL-1β binds to IL-1R1 and IL-1R accessory protein (IL-1RAcP), and IL-18 binds to IL-18R-alpha and IL-18R-beta to initiate effector functions on target cells [103].

This theory is enriched by the genetic findings on the main genes of classic autoinflammatory monogenic diseases not only in syndromic PG, like PASH, but also in isolated PG [84, 105]. In particular, some of us found a number of mutations in Familial Mediterranean Fever Gene (MEFV), NLRP3, NLRP12, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2 (NOD2), Lipin 2 (LPIN2) and PSTPIP1 in PG and its syndromic form [105]. Based on these findings, it is possible to hypothesize that PG and PASH are different phenotypes of a spectrum of autoinflammatory polygenic conditions. The paradigmatic autoinflammatory syndrome presenting with PG, PAPA syndrome, is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion as result of two main mutations, A230T and E250Q, involving the PSPPIP-1 gene [106,107,108,109,110,111]. Mutated PSPPIP-1 leads to decreased inhibition of the inflammasome and consequent activation of caspase-1, which in turn leads to an increased production of IL-1β that drives the autoinflammation associated with the PAPA triad [107]. There are also familial cases of PG in which no specific mutations have been reported [112].

Recent studies showed in lesional skin of different neutrophilic dermatoses, such as PG, SS and APF, a peculiar cytokine expression profile, which seems to confirm the important autoinflammatory component in their pathogenesis [69, 112,113,114,115].

In particular, a comprehensive immunological investigation on 13 patients with PG and 7 patients with PASH syndrome showed in lesional skin of both conditions a constant inflammatory profile with overexpression of IL-1β, IL-17, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-8 and the other chemokines C-X-C motif ligand (CXCL) 1, 2, and 3 and CXCL16 [10]. The overexpression of IL-1β and its receptor suggests the involvement of autoinflammation through the activation of inflammasome in PG similarly to the PG-associated syndromes, like the classic monogenic autoinflammatory syndrome PAPA [116]. IL-17 is a pivotal cytokine in regulating the innate immune response, but it is also crucial in autoinflammation recruiting neutrophils, activating them and stimulating their production of IL-8 [117]. IL-8 is the main chemoattractor of neutrophils and acts synergically with TNF-α in maintaining the pro-inflammatory profile. In line with these findings, an imbalance of T regulatory cells and T helper 17 effector cells in patients with PG has been described [118].

IL-1β, IL-17 and TNF-α increase both production and activation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP), like MMP-2 and MMP-9, responsible to tissue damage. MMP-9 is overexpressed in inflammatory infiltrate of PG, while MMP-2 is commonly involved in several neutrophilic dermatoses [113, 114]. The overproduction of MMPs is partially balanced by the overproduction of tissue inhibitor metalloproteinases; either way, the final result is equally a great inflammatory insult and the consequent destruction of the targeted tissue [113, 114].

It is noteworthy that IL-1β, IL-17 and TNF-α are also elevated in the lesional skin of other neutrophilic dermatoses, including SS and APF [69, 119, 120].

The pathophysiological model of autoinflammation in neutrophilic diseases is summarized in Fig. 6 [12].

Pathophysiological model of autoinflammation in neutrophilic diseases. Mutations of a gene regulating innate immunity such as PSTPIP1 (proline–serine–threonine phosphatase-interacting protein 1) induce activation of the inflammasome via increased binding affinity to pyrin. This molecular platform is responsible for the activation of caspase-1, an enzyme that proteolytically cleaves pro-IL (pro-interleukin)-1-beta to its active isoform IL-1-beta. This pivotal cytokine is thus overproduced, leading to an uncontrolled release of a number of pro-inflammatory cytokines (particularly IL-17), chemokines and other effector molecules responsible for neutrophil-mediated autoinflammation. Inhibitory signals carried by molecules such as TIMP-1 (tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1), TIMP-2, Siglec-5 (sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-type lectin-5) and Siglec-9 represent an attempt to dampen inflammation. CXCL chemokine (CXC motif) ligand, E-selectin endothelial selectin, L-selectin leucocyte selectin, MCP monocyte chemotactic protein, MMP matrix metalloproteinase, RANTES regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted, TNF tumour necrosis factor

Therapeutic Approach

Only two randomized controlled trials in patients with neutrophilic diseases are reported in the literature [121, 122]. In particular, in the first study [121], infliximab has been reported to be superior to placebo in the treatment of PG [122], and in the second one, prednisolone and ciclosporin, the most used agents in PG treatment, did not differ in efficacy. Systematic reviews have primarily relied on anecdotal reports or retrospective case series [123, 124].

Systemic steroids, namely oral prednisone at the initial dose of 0.5–1.0 mg/kg/day, are the mainstay of treatment in all neutrophilic diseases [5, 125]. High-strength topical corticosteroids or topical calcineurin inhibitors can be coadministered [126]. Other immunosuppresants, notably ciclosporin (3–4 mg/kg/day) or immunomodulating agents, particularly dapsone (1.0–1.5 mg/kg/day), can be alternative options or can be used as steroid-sparing drugs [21, 76, 122, 127]. Corticosteroid treatment is usually continued at full dosage until clinical remission and then used at progressively tapering doses (approximately by 5 mg of oral prednisone per week) over a period varying from 3 to 12 months. However, cases unresponsive to these classic immunosuppressive regimens are relatively common. Modern treatment options oriented towards key mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of the disease, namely inflammatory mediators, would be potentially the most effective therapeutic option. In line with this view, medications targeting IL-1 and TNF-α, with blocking of the inflammatory cascade at different levels, are usually successful in managing cases unresponsive or refractory to conventional drugs. To date, among IL-1 inhibitors, the effect of anakinra, which blocks the IL-1 receptor and thereby decreases the activity of IL-1α and IL-1β, is the most thoroughly documented in the treatment of PG, both in syndromic and isolated forms, and APF [94, 100, 119, 128,129,130,131,132,133]. Canakinumab, a monoclonal antibody that selectively blocks IL-1β, has been found to be an effective and well-tolerated treatment for idiopathic, steroid-refractory PG as well as for PAPA and PASH syndrome [134,135,136]. To the best of our knowledge, no randomized controlled trials are available on the use of anakinra and canakinumab in the management of neutrophilic diseases. The experience in the treatment of neutrophilic diseases with these two drugs comes from anecdotal reports or small case series [131, 136]. Anakinra is administered subcutaneously at a daily dose of 100 mg. After approximately 6 months, the injection interval can be prolonged (two to three times weekly) and the drug can be stopped several months to few years later depending on the clinical response. Common side effects of anakinra include injection site reactions, headaches and neutropenia; serious infections are rare [131]. Canakinumab is administered subcutaneously at a dose of 150 mg at week 0 and week 2 with a possible repeated injection at week 8 in case of poor response [136]. Canakinumab is usually well tolerated; side effects include hypertensive episodes, lumbago and infections [137].

In addition to IL-1, TNF-α is the other cytokine that plays a major role in the pathogenesis of neutrophilic dermatoses. The most consistent responses have been observed with the anti-TNF-α antagonists etanercept, adalimumab and infliximab [69, 138,139,140]. The overexpression of IL-17 in lesional skin of both isolated and syndromic PG [84, 114] provides the rationale for the possible clinical use of IL-17 antagonists in these conditions, as it has been done in the treatment of psoriasis with two of these agents, namely secukinumab and ixekizumab [141, 142].

Although promising, the results of therapy with biological agents are variable and cases that are refractory to these treatments have been reported. It can be hypothesized that the use of biological agents as monotherapy may be not able to affect the entire inflammatory cascade or to simultaneously influence all of its levels. Combined therapy with different groups of biological agents aimed to affect more than one link in the inflammatory cascade may allow achieving maximum therapeutic effectiveness.

Conclusions

Neutrophils are key players in inflammatory responses and are the first line of defence against harmful stimuli. However, dysregulation of neutrophil homeostasis can result in excessive inflammation and subsequent tissue damage. Neutrophilic diseases are a spectrum of inflammatory conditions characterized by polymorphic cutaneous lesions resulting from a neutrophil-rich inflammatory infiltrate in the absence of infection and by possible involvement of almost any organ system. Neutrophilic diseases may be considered autoinflammatory in origin based on the overexpression of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1-beta, IL-17 and TNF-alpha in the absence of infection, allergy and high titer of circulating autoantibodies or autoreactive T cells. Molecular mechanisms causing autoinflammatory monogenic diseases are also relevant in neutrophilic diseases, which may be regarded as a spectrum of polygenic autoinflammatory conditions. Indeed, mutations of PSTPIP1, the gene of PAPA, as well as of a number of other genes involved in classic autoinflammatory diseases are likely to play a role in the pathogenesis of both isolated and syndromic PG as well as in neutrophilic diseases in general. Classic regimens such as systemic glucocorticosteroids and immunosuppressants are the mainstay of treatment. Biological drugs specifically targeting pro-inflammatory cytokines are useful in refractory cases.

References

Ahronowitz I, Harp J, Shinkai K (2012) Etiology and management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol 13:191–211. doi:10.2165/11595240-000000000-00000

Wallach D, Vignon-Pennamen MD (2006) From acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis to neutrophilic disease: forty years of clinical research. J Am Acad Dermatol 55:1066–1071. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.07.016

Kastner DL, Aksentijevich I, Goldbach-Mansky R (2010) Autoinflammatory disease reloaded: a clinical perspective. Cell 140:784–790. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.002

Alavi A, French LE, Davis MD, Brassard A, Kirsner RS (2017) Pyoderma gangrenosum: an update on pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol (in press). doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0251-7

Wallach D, Vignon-Pennamen MD (2015) Pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet syndrome: the prototypic neutrophilic dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.13955

Prat L, Bouaziz JD, Wallach D, Vignon-Pennamen MD, Bagot M (2014) Neutrophilic dermatoses as systemic diseases. Clin Dermatol 32:376–388. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.11.004

Marzano AV, Borghi A, Stadnicki A, Crosti C, Cugno M (2014) Cutaneous manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: pathophysiology, clinical features, and therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis 20:213–227. doi:10.1097/01.MIB.0000436959.62286.f9

Callen JP (1998) Pyoderma gangrenosum. Lancet 351:581–585. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10187-8

Jaimes-Lopez N, Molina V, Arroyave JE, Vasquez LA, Ruiz AC, Castano R, Ruiz MH (2009) Development of pyoderma gangrenosum during therapy with infliximab. J Dermatol Case Rep 3:20–23. doi:10.3315/jdcr.2009.1027

White LE, Villa MT, Petronic-Rosic V, Jiang J, Medenica MM (2006) Pyoderma gangrenosum related to a new granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Skinmed 5:96–98

Sagara R, Kitami A, Nakada T, Iijima M (2006) Adverse reactions to gefitinib (Iressa): revealing sycosis- and pyoderma gangrenosum-like lesions. Int J Dermatol 45:1002–1003. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02749.x

Marzano AV, Borghi A, Meroni PL, Cugno M (2016) Pyoderma gangrenosum and its syndromic forms: evidence for a link with autoinflammation. Br J Dermatol 175:882–891. doi:10.1111/bjd.14691

Cugno M, Borghi A, Marzano AV (2017) PAPA, PASH and PAPASH syndromes: pathophysiology, Presentation and Treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0265-1

Langan SM, Groves RW, Card TR, Gulliford MC (2012) Incidence, mortality, and disease associations of pyoderma gangrenosum in the United Kingdom: a retrospective cohort study. J Invest Dermatol 132:2166–2170. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.130

Von den Driesch P (1997) Pyoderma gangrenosum: a report of 44 cases with follow-up. Br J Dermatol 137:1000–1005

Marzano AV, Trevisan V, Lazzari R, Crosti C (2011) Pyoderma gangrenosum: study of 21 patients and proposal of a ‘clinicotherapeutic’ classification. J Dermatol Treat 22:254–260. doi:10.3109/09546631003686069

Varol A, Seifert O, Anderson CD (2010) The skin pathergy test: innately useful? Arch Dermatol Res 302:155–168. doi:10.1007/s00403-009-1008-9

Tolkachjov SN, Fahy AS, Wetter DA, Brough KR, Bridges AG, Davis MD, El-Azhary RA, McEvoy MT, Camilleri MJ (2015) Postoperative pyoderma gangrenosum (PG): the Mayo Clinic experience of 20 years from 1994 through 2014. J Am Acad Dermatol 73:615–622. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.054

Tuffaha SH, Sarhane KA, Mundinger GS, Broyles JM, Reddy SK, Azoury SC, Seal S, Cooney DS, Bonawitz SC (2016) Pyoderma gangrenosum after breast surgery: diagnostic pearls and treatment recommendations based on a systematic literature review. Ann Plast Surg 77:e39–e44. doi:10.1097/SAP.0000000000000248

Barbosa NS, Tolkachjov SN, El-Azhary RA, Davis MD, Camilleri MJ, McEvoy MT, Bridges AG, Wetter DA (2016) Clinical features, causes, treatments, and outcomes of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum (PPG) in 44 patients: the Mayo Clinic experience, 1996 through 2013. J Am Acad Dermatol 75:931–939. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.05.044

Marzano AV, Ishak RS, Saibeni S, Crosti C, Meroni PL, Cugno M (2013) Autoinflammatory skin disorders in inflammatory bowel diseases, pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet’s syndrome: a comprehensive review and disease classification criteria. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 45:202–210. doi:10.1007/s12016-012-8351-x

Perry HO, Winkelmann RK (1972) Bullous pyoderma gangrenosum and leukemia. Arch Dermatol 106:901–905

Ho KK, Otridge BW, Vandenberg E, Powell FC (1992) Pyoderma gangrenosum, polycythemia rubra vera, and the development of leukemia. J Am Acad Dermatol 27:804–808

Marzano AV, Tourlaki A, Alessi E, Caputo R (2008) Widespread idiopathic pyoderma gangrenosum evolved from ulcerative to vegetative type: a 10-year history with a recent response to infliximab. Clin Exp Dermatol 33:156–159. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02607.x

Bennett ML, Jackson JM, Jorizzo JL, Fleischer AB Jr, White WL, Callen JP (2000) Pyoderma gangrenosum. A comparison of typical and atypical forms with an emphasis on time to remission. Case review of 86 patients from 2 institutions. Medicine (Baltimore) 79:37–46

Hughes AP, Jackson JM, Callen JP (2000) Clinical features and treatment of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum. JAMA 284:1546–1548

Brunsting LA, Goeckerman WH, O’Leary PA (1930) Pyoderma (ecthyma) gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol Syphilol 22:655–680

Powell FC, Su WP, Perry HO (1996) Pyoderma gangrenosum: classification and management. J Am Acad Dermatol 34:395–409

Ruocco E, Sangiuliano S, Gravina AG, Miranda A, Nicoletti G (2009) Pyoderma gangrenosum: an updated review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 23:1008–1017. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03199.x

Langan SM, Powell FC (2005) Vegetative pyoderma gangrenosum: a report of two new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol 44:623–629. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02591.x

Kitagawa KH, Grassi M (2008) Primary pyoderma gangrenosum of the lungs. J Am Acad Dermatol 59(5 Suppl):S114–S116. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.017

Vignon-Pennamen MD, Wallach D (1995) The neutrophilic disease: a review of extracutaneous neutrophilic manifestations. Eur J Dermatol 5:449–455

Marzano AV, Ishak RS, Lazzari R, Polloni I, Vettoretti S, Crosti C (2012) Vulvar pyoderma gangrenosum with renal involvement. Eur J Dermatol 22(4):537–539. doi:10.1684/ejd.2012.1776

Su WP, Davis MD, Weenig RH, Powell FC, Perry HO (2004) Pyoderma gangrenosum: clinicopathologic correlation and proposed diagnostic criteria. Int J Dermatol 43:790–800. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02128.x

Marzano AV, Trevisan V, Galloni C, Alessi E (2008) Fatal bullous pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with Klinefelter’s syndrome. Acta Derm Venereol 88:158–159. doi:10.2340/00015555-0346

Binus AM, Qureshi AA, Li VW, Winterfield LS (2011) Pyoderma gangrenosum: a retrospective review of patient characteristics, comorbidities and therapy in 103 patients. Br J Dermatol 165:1244–1250. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10565.x

Koester G, Tarnower A, Levisohn D, Burgdorf W (1993) Bullous pyoderma gangrenosum. J Am Acad Dermatol 29:875–878

Sweet RD (1964) An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol 76:349–356

Rochet NM, Chavan RN, Cappel MA, Wada DA, Gibson LE (2013) Sweet syndrome: clinical presentation, associations, and response to treatment in 77 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 69:557

Cohen PR (2007) Sweet’s syndrome—a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2:34. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-34

von den Driesch P, Gomez RS, Kiesewetter F, Hornstein OP (1989) Sweet’s syndrome: clinical spectrum and associated conditions. Cutis 44:193–200

Cohen PR, Kurzrock R (1989) Diagnosing the Sweet syndrome. Ann Intern Med 110:573–574

Boatman BW, Taylor RC, Klein LE (1994) Sweet’s syndrome in children. South Med J 87:193–196

Sommer S, Wilkinson SM, Merchant WJ, Goulden V (2000) Sweet’s syndrome presenting as palmoplantar pustulosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 42:332–334

Sutra-Loubet C, Carlotti A, Guillemette J, Wallach D (2004) Neutrophilic lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 50:280–285. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.10.006

Chan MP, Duncan LM, Nazarian RM (2013) Subcutaneous Sweet syndrome in the setting of myeloid disorders: a case series and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol 68:1006–1015. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.12.954

Drago F, Ciccarese G, Agnoletti AF, Sarocchi F, Parodi A (2017) Neuro sweet syndrome: a systematic review. A rare complication of Sweet syndrome. Acta Neurol Belg 117:33–42

von den Driesch P (1994) Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol 31:535–556

Kemmett D, Hunter JAA (1990) Sweet’s syndrome: a clinicopathologic review of twenty-nine cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 23:503–507

Sitjas D, Cuatrecasas M, De Moragas JM (1993) Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome). Int J Dermatol 32:261–268

Muster AJ, Bharati S, Herman JJ, Esterly NB, Gonzales-Crussi F, Holbrook KA (1983) Fatal cardiovascular disease and cutis laxa following acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. J Pediatr 102:243–248

Attias D, Laor R, Zuckermann E, Naschitz JE, Luria M, Misselevitch I, Boss JH (1995) Acute neutrophilic myositis in Sweet’s syndrome: late phase transformation into fibrosing myositis and panniculitis. Hum Pathol 26:687–690

Walker DC, Cohen PR (1996) Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-associated acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis: case report and review of drug induced Sweet’s syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 34:918–923

Mensing H, Kowalzick L (1991) Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome) caused by minocycline. Dermatologica 182:43–46

Thompson DF, Montarella KE (2007) Drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome. Ann Pharmacother 41:802–811. doi:10.1345/aph.1H563

Marzano AV, Capsoni F, Berti E, Gasparini G, Bottelli S, Caputo R (1996) Amicrobial pustular dermatosis of cutaneous folds associated with autoimmune disorders: a new entity? Dermatology 193:88–93

Lagrange S, Chosidow O, Flette JC, Wechsler B, Godeau P, Frances C (1997) A peculiar form of amicrobial pustulosis of the folds associated with systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune diseases. Lupus 6:514–520

Stefanidou MP, Kanavaros PE, Stefanaki KS, Tosca AD (1998) Amicrobial pustulosis of the folds: a cutaneous manifestation associated with connective tissue disease. Dermatology 197:394–396

Kuyama M, Fujimoto W, Kambara H, Egusa M, Saitoh M, Yamasaki O, Maehara K, Ohara A, Arata J, Iwatsuki K (2002) Amicrobial pustular dermatosis in two patients with immunological abnormalities. Clin Exp Dermatol 27:286–289

Kerl K, Masouyé I, Lesavre P, Saurat JH, Borradori L (2005) A case of amicrobial pustulosis of the folds associated with neutrophilic gastrointestinal involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus. Dermatology 211:356–359. doi:10.1159/000088508

Marzano AV, Ramoni S, Caputo R (2008) Amicrobial pustulosis of the folds. Report of 6 cases and a literature review. Dermatology 216:305–311. doi:10.1159/000113942

Méndez-Flores S, Charli-Joseph Y, Saeb-Lima M, Orozco-Topete R, Fernández Sánchez M (2013) Amicrobial pustulosis of the folds associated with autoimmune disorders: systemic lupus erythematosus case series and first report on the association with autoimmune hepatitis. Dermatology 226:1–4. doi:10.1159/000343595

Crickx B, Diego ML, Guillevin L, Picard C, Grossins M, Belaïch S (1991) Pustulose amicrobienne et lupus érythémateux systémique. Communication n° 11 (letter). Journées Dermatologiques de Paris París, March 1991

Oberlin P, Bagot M, Perrussel M, Leteinturier F, Wechsler J, Revuz J (1991) Pustulose amicrobienne et lupus érythémateux systémique. Ann Dermatol Vénéréol 118:824–825

Saiag PH, Blanc F, Marinho E, De La Blanchardière A, Leconte I, Cocheton JJ, Tulliez M (1993) Pustulose amicrobienne et lupus érythémateux systémique: un cas. Ann Dermatol Vénéréol 120:779–781

Bénéton N, Wolkenstein P, Bagot M, Cosnes A, Wechsler J, Roujeau JC, Revuz J (2000) Amicrobial pustulosis associated with autoimmune diseases: healing with zinc supplementation. Br J Dermatol 143:1306–1310

Claeys A, Bessis D, Cheikhrouhou H, Pouaha J, Cuny JF, Truchetet F (2011) Amicrobial pustulosis of the folds revealing asymptomatic autoimmune thyroiditis. Eur J Dermatol 21:641–642. doi:10.1684/ejd.2011.1406

Lim YL, Ng SK, Lian TY (2012) Amicrobial pustulosis associated with autoimmune disease in a patient with Sjögren syndrome and IgA nephropathy. Clin Exp Dermatol 37:374–378. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04262.x

Marzano AV, Tavecchio S, Berti E, Gelmetti C, Cugno M (2015) Cytokine and chemokine profile in amicrobial pustulosis of the folds: evidence for autoinflammation. Medicine (Baltimore) 94:e2301. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000002301

Marzano AV, Tavecchio S, Berti E, Gelmetti C, Cugno M (2015) Paradoxical autoinflammatory skin reaction to tumor necrosis factor alpha blockers manifesting as amicrobial pustulosis of the folds in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Medicine (Baltimore) 94:e1818. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000001818

Vignon-Pennamen MD, Wallach D (1991) Cutaneous manifestations of neutrophilic disease. Dermatologica 183:255–264

Natsuga K, Sawamura D, Homma E, Nomura T, Abe M, Muramatsu R, Mochizuki T, Koike T, Shimizu H (2007) Amicrobial pustulosis associated with IgA nephropathy and Sjögren’s syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 57:523–526. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.05.023

Hoch O, Herbst RA, Gutzmer R, Kiehl P, Kapp A, Weiss J (1998) Amicrobial intertriginous pustulosis in autoimmune disease: a new entity? Hautarzt 49:634–640

López-Navarro N, Alcaide A, Gallego E, Herrera-Acosta E, Gallardo M, Bosch RJ, Herrera E (2009) Amicrobial pustulosis of the folds associated with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Clin Exp Dermatol 34:e561–e563. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03370.x

Lee HY, Pelivani N, Beltraminelli H, Hegyi I, Yawalkar N, Borradori L (2011) Amicrobial pustulosis-like rash in a patient with Crohn’s disease under anti-TNF-alpha blocker. Dermatology 222:304–310. doi:10.1159/000329428

Boms S, Gambichler T (2006) Review of literature on amicrobial pustulosis of the folds associated with autoimmune disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol 7:369–374

Naik HB, Cowen EW (2013) Autoinflammatory pustular neutrophilic diseases. Dermatol Clin 31:405–425. doi:10.1016/j.det.2013.04.001

Wise CA, Gillum JD, Seidman CE, Lindor NM, Veile R, Bashiardes S, Lovett M (2002) Mutations in CD2BP1 disrupt binding to PTP PEST and are responsible for PAPA syndrome, an autoinflammatory disorder. Hum Mol Genet 11:961–969

Smith EJ, Allantaz F, Bennett L, Zhang D, Gao X, Wood G, Kastner DL, Punaro M, Aksentijevich I, Pascual V, Wise CA (2010) Clinical, molecular, and genetic characteristics of PAPA syndrome: a review. Curr Genomics 11:519–527. doi:10.2174/138920210793175921

Kistowska M, Gehrke S, Jankovic D, Kerl K, Fettelschoss A, Feldmeyer L, Fenini G, Kolios A, Navarini A, Ganceviciene R, Schauber J, Contassot E, French LE (2014) IL-1β drives inflammatory responses to Propionibacterium acnes in vitro and in vivo. J Invest Dermatol 134:677–685. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.438

Qin M, Pirouz A, Kim MH, Krutzik SR, Garbán HJ, Kim J (2014) Propionibacterium acnes induces IL-1β secretion via the NLRP3 inflammasome in human monocytes. J Invest Dermatol 134:381–388. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.309

Li ZJ, Choi DK, Sohn KC, Seo MS, Lee HE, Lee Y, Seo YJ, Lee YH, Shi G, Zouboulis CC, Kim CD, Lee JH, Im M (2014) Propionibacterium acnes activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in human sebocytes. J Invest Dermatol 134:2747–2756. doi:10.1038/jid.2014.221

Braun-Falco M, Kovnerystyy O, Lohse P, Ruzicka T (2012) Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH)—a new autoinflammatory syndrome distinct from PAPA syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 66:409–415. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.12.025

Marzano AV, Ceccherini I, Gattorno M, Fanoni D, Caroli F, Rusmini M, Grossi A, De Simone C, Borghi OM, Meroni PL, Crosti C, Cugno M (2014) Association of pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH) shares genetic and cytokine profiles with other autoinflammatory diseases. Medicine (Baltimore) 93:e187. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000000187

van der Zee HH, Horvath B, Jemec GB, Prens EP (2016) The association between hidradenitis suppurativa and Crohn’s disease: in search of the missing pathogenic link. J Invest Dermatol 136:1747–1748. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2016.05.102

Damiani G, Della Valle V, Iannone M, Dini V, Marzano AV (2016) Autoinflammatory Disease Damage Index (ADDI): a possible newborn also in hidradenitis suppurativa daily practice. Ann Rheum Dis (in press). doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210901

Marzano AV (2016) Hidradenitis suppurativa, neutrophilic dermatoses and autoinflammation: what’s the link? Br J Dermatol 174:482–483. doi:10.1111/bjd.14364

Jemec GB (2012) Clinical practice. Hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med 366:158–164. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1014163

Dessinioti C, Katsambas A, Antoniou C (2014) Hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa) as a systemic disease. Clin Dermatol 32:397–408. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.11.006

Zouboulis CC, Desai N, Emtestam L, Hunger RE, Ioannides D, Juhász I, Lapins J, Matusiak L, Prens EP, Revuz J, Schneider-Burrus S, Szepietowski JC, van der Zee HH, Jemec GB (2015) European S1 guideline for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 29:619–644. doi:10.1111/jdv.12966

Duchatelet S, Miskinyte S, Join-Lambert O, Ungeheuer MN, Francès C, Nassif A, Hovnanian A (2015) First nicastrin mutation in PASH (pyoderma gangrenosum, acne and suppurative hidradenitis) syndrome. Br J Dermatol 173:610–612. doi:10.1111/bjd.13668

Calderón-Castrat X, Bancalari-Diaz D, Román-Curto C, Romo-Melgar A, Amorós-Cerdán D, Alcaraz-Mas LA, Fernández-López E, Cañueto J (2016) PSTPIP1 gene mutation in a pyoderma gangrenosum, acne and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH) syndrome. Br J Dermatol 175:194–198. doi:10.1111/bjd.14383

Bruzzese V (2012) Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne conglobata, suppurative hidradenitis, and axial spondyloarthritis: efficacy of anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy. J Clin Rheumatol 18:413–415. doi:10.1097/RHU.0b013e318278b84c

Marzano AV, Trevisan V, Gattorno M, Ceccherini I, De Simone C, Crosti C (2013) Pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and hidradenitis suppurativa (PAPASH): a new autoinflammatory syndrome associated with a novel mutation of the PSTPIP1 gene. JAMA Dermatol 149:762–764. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.2907

Garzorz N, Papanagiotou V, Atenhan A, Andres C, Eyerich S, Eyerich K, Ring J, Brockow K (2016) Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, psoriasis, arthritis and suppurative hidradenitis (PAPASH)-syndrome: a new entity within the spectrum of autoinflammatory syndromes? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 30:141–143. doi:10.1111/jdv.12631

Saraceno R, Babino G, Chiricozzi A, Zangrilli A, Chimenti S (2015) PsAPASH: a new syndrome associated with hidradenitis suppurativa with response to tumor necrosis factor inhibition. J Am Acad Dermatol 72:e42–e44. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.10.002

Navarini AA, Satoh TK, French LE (2016) Neutrophilic dermatoses and autoinflammatory diseases with skin involvement–innate immune disorders. Semin Immunopathol 38:45–56. doi:10.1007/s00281-015-0549-6

Satoh TK, Mellett M, Contassot E, French LE (2016) Are neutrophilic dermatoses autoinflammatory disorders? Br J Dermatol (in press). doi:10.1111/bjd.15105

McDermott MF, Aksentijevich I, Galon J, McDermott EM, Ogunkolade BW, Centola M, Mansfield E, Gadina M, Karenko L, Pettersson T, McCarthy J, Frucht DM, Aringer M, Torosyan Y, Teppo AM, Wilson M, Karaarslan HM, Wan Y, Todd I, Wood G, Schlimgen R, Kumarajeewa TR, Cooper SM, Vella JP, Amos CI, Mulley J, Quane KA, Molloy MG, Ranki A, Powell RJ, Hitman GA, O’Shea JJ, Kastner DL (1999) Germline mutations in the extracellular domains of the 55 kDa TNF receptor, TNFR1, define a family of dominantly inherited autoinflammatory syndromes. Cell 97:133–144

Dinarello CA (2011) Interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory diseases. Blood 117:3720–3732. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-07-273417

Broderick L, De Nardo D, Franklin BS, Hoffman HM, Latz E (2015) The inflammasomes and autoinflammatory syndromes. Annu Rev Pathol 10:395–424. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-012414-040431

Hoffman HM, Mueller JL, Broide DH, Wanderer AA, Kolodner RD (2001) Mutation of a new gene encoding a putative pyrin-like protein causes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wells syndrome. Nat Genet 29:301–305

Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J (2002) The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell 10:417–426

Saïd-Sadier N, Ojcius DM (2012) Alarmins, inflammasomes and immunity. Biom J 35:437–449. doi:10.4103/2319-4170.104408

Marzano AV, Damiani G, Ceccherini I, Berti E, Gattorno M, Cugno M (2016) Autoinflammation in pyoderma gangrenosum and its syndromic form PASH. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.15226

Tallon B, Corkill M (2006) Peculiarities of PAPA syndrome. Rheumatology 45:1140–1143. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kei178

Yeon HB, Lindor NM, Seidman JG, Seidman CE (2000) Pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne syndrome maps to chromosome 15q. Am J Hum Genet 66:1443–1448

Heymann MC, Rosen-Wolff A (2013) Contribution of the inflammasomes to autoinflammatory diseases and recent mouse models as research tools. Clin Immunol 147:175–184. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2013.01.006

Wollina U, Tchernev G (2014) Pyoderma gangrenosum: pathogenetic oriented treatment approaches. Wien Med Wochenschr 164:263–273. doi:10.1007/s10354-014-0285-x

Wollina U, Haroske G (2011) Pyoderma gangraenosum. Curr Opin Rheumatol 23:50–56. doi:10.1097/BOR.0b013e328341152f

Palanivel JA, Macbeth AE, Levell NJ (2013) Pyoderma gangrenosum in association with Janus kinase 2 (JAK2V617F) mutation. Clin Exp Dermatol 38:44–46. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04375.x

DeFilippis EM, Feldman SR, Huang WW (2015) The genetics of pyoderma gangrenosum and implications for treatment: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol 172:1487–1497. doi:10.1111/bjd.13493

Marzano AV, Cugno M, Trevisan V, Fanoni D, Venegoni L, Berti E, Crosti C (2010) Role of inflammatory cells, cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases in neutrophil-mediated skin diseases. Clin Exp Immunol 162:100–107. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04201.x

Marzano AV, Fanoni D, Antiga E, Quaglino P, Caproni M, Crosti C, Meroni PL, Cugno M (2014) Expression of cytokines, chemokines and other effector molecules in two prototypic autoinflammatory skin diseases, pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet’s syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol 178:48–56. doi:10.1111/cei.12394

Lima AL, Karl I, Giner T, Poppe H, Schmidt M, Presser D, Goebeler M, Bauer B (2016) Keratinocytes and neutrophils are important sources of proinflammatory molecules in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol 174:514–521. doi:10.1111/bjd.14214

Shoham NG, Centola M, Mansfield E, Hull KM, Wood G, Wise CA, Kastner DL (2003) Pyrin binds the PSTPIP1/CD2BP1 protein, defining familial Mediterranean fever andPAPA syndrome as disorders in the same pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:13501–13506. doi:10.1073/pnas.2135380100

Braswell SF, Kostopoulos TC, Ortega-Loayza AG (2015) Pathophysiology of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG): an updated review. J Am Acad Dermatol 73:691–698. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.021

Caproni M, Antiga E, Volpi W, Verdelli A, Venegoni L, Quaglino P, Fabbri P, Marzano AV (2015) The Treg/Th17 cell ratio is reduced in the skin lesions of patients with pyoderma gangrenosum. Br J Dermatol 173:275–278. doi:10.1111/bjd.13670

Amazan E, Ezzedine K, Mossalayi MD, Taieb A, Boniface K, Seneschal J (2014) Expression of interleukin-1 alpha in amicrobial pustulosis of the skin folds with complete response to anakinra. J Am Acad Dermatol 71:e53–e56. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.041

Marzano AV, Cugno M, Trevisan V, Lazzari R, Fanoni D, Berti E, Crosti C (2011) Inflammatory cells, cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases in amicrobialpustulosis of the folds and other neutrophilic dermatoses. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 24:451–460. doi:10.1177/039463201102400218

Brooklyn TN, Dunnill MG, Shetty A, Bowden JJ, Williams JD, Griffiths CE, Forbes A, Greenwood R, Probert CS (2006) Infliximab for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut 55:505–509. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.074815

Ormerod AD, Thomas KS, Craig FE, Mitchell E, Greenlaw N, Norrie J, Mason JM, Walton S, Johnston GA, Williams HC, UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network’s STOP GAP Team (2015) Comparison of the two most commonly used treatments for pyoderma gangrenosum: results of the STOP GAP randomised controlled trial. BMJ 350:h2958. doi:10.1136/bmj.h2958

Reichrath J, Bens G, Bonowitz A, Tilgen W (2005) Treatment recommendations for pyoderma gangrenosum: an evidence-based review of the literature based on more than 350 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 53:273–283. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2004.10.006

Miller J, Yentzer BA, Clark A, Jorizzo JL, Feldman SR (2010) Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review and update on new therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol 62:646–654. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2009.05.030

Maalouf D, Battistella M, Bouaziz JD (2015) Neutrophilic dermatosis: disease mechanism and treatment. Curr Opin Hematol 22:23–29. doi:10.1097/MOH.0000000000000100

Thomas KS, Ormerod AD, Craig FE, Greenlaw N, Norrie J, Mitchell E, Mason JM, Johnston GA, Wahie S, Williams HC, UK Dermatology Clinical Trials Network’s STOP GAP Team (2016) Clinical outcomes and response of patients applying topical therapy for pyoderma gangrenosum: a prospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol 75:940–949. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.06.016

Bhat YJ, Hassan I, Sajad P, Akhtar S, Sheikh S (2015) Sweet’s syndrome: an evidence-based report. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 25:525–527

Chokoeva AA, Cardoso JC, Wollina U, Tchernev G (2017) Pyoderma gangrenosum—a novel approach? Wien Med Wochenschr 167(3–4):58–65. doi:10.1007/s10354-016-0472-z

Pazyar N, Feily A, Yaghoobi R (2012) An overview of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, anakinra, in the treatment of cutaneous diseases. Curr Clin Pharmacol 7:271–275

Lukens JR, Kanneganti TD (2014) SHP-1 and IL-1α conspire to provoke neutrophilic dermatoses. Rare Dis 2:e27742. doi:10.4161/rdis.27742

Brenner M, Ruzicka T, Plewig G, Thomas P, Herzer P (2009) Targeted treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum in PAPA (pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum and acne) syndrome with the recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist anakinra. Br J Dermatol 161:1199–1201. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09404.x

Dierselhuis MP, Frenkel J, Wulffraat NM, Boelens JJ (2005) Anakinra for flares of pyogenic arthritis in PAPA syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 44:406–408. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keh479

Dinarello CA, van der Meer JW (2013) Treating inflammation by blocking interleukin-1 in humans. Semin Immunol 25:469–484. doi:10.1016/j.smim.2013.10.008

Jaeger T, Andres C, Grosber M, Zirbs M, Hein R, Ring J, Traidl-Hoffmann C (2013) Pyoderma gangrenosum and concomitant hidradenitis suppurativa—rapid response to canakinumab (anti-IL-1β). Eur J Dermatol 23:408–410. doi:10.1684/ejd.2013.2018

Geusau A, Mothes-Luksch N, Nahavandi H, Pickl WF, Wise CA, Pourpak Z, Ponweiser E, Eckhart L, Sunder-Plassmann R (2013) Identification of a homozygous PSTPIP1 mutation in a patient with a PAPA-like syndrome responding to canakinumab treatment. JAMA Dermatol 149:209–215. doi:10.1001/2013.jamadermatol.717

Kolios AG, Maul JT, Meier B, Kerl K, Traidl-Hoffmann C, Hertl M, Zillikens D, Röcken M, Ring J, Facchiano A, Mondino C, Yawalkar N, Contassot E, Navarini AA, French LE (2015) Canakinumab in adults with steroid-refractory pyoderma gangrenosum. Br J Dermatol 173:1216–1223. doi:10.1111/bjd.14037

Krause K, Tsianakas A, Wagner N, Fischer J, Weller K, Metz M, Church MK, Maurer M (2017) Efficacy and safety of canakinumab in Schnitzler syndrome: a multicenter randomized placebo-controlled study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 139:1311–1320. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.041

Stichweh DS, Punaro M, Pascual V (2005) Dramatic improvement of pyoderma gangrenosum with infliximab in a patient with PAPA syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol 22:262–265. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2005.22320.x

Tofteland ND, Shaver TS (2010) Clinical efficacy of etanercept for treatment of PAPA syndrome. J Clin Rheumatol 16:244–245. doi:10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181e969b9

Lee H, Park SH, Kim SK, Choe JY, Park JS (2012) Pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne syndrome (PAPA syndrome) with E250K mutation in CD2BP1 gene treated with the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab. Clin Exp Rheumatol 30:452

Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, Reich K, Griffiths CE, Papp K, et al (2014) ERASURE Study Group.; FIXTURE Study Group. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis-results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med 371:326–338. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314258

Burkett PR, Kuchroo VK (2016) IL-17 blockade in psoriasis. Cell 167:1669. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.044

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

None.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

Not necessary.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marzano, A.V., Borghi, A., Wallach, D. et al. A Comprehensive Review of Neutrophilic Diseases. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol 54, 114–130 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-017-8621-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-017-8621-8