Abstract

Since 1989, clinical ethics consultation in form of hospital ethics committees (HECs) was established in most of the transition countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Up to now, the similarities and differences between HECs in Central and Eastern Europe and their counterparts in the U.S. and Western Europe have not been determined. Through search in literature databases, we have identified studies that document the implementation of clinical ethics consultation in Central and Eastern Europe. These studies have been analyzed under the following aspects: mode of establishment of HECs, character of consultation they provide, and their composition. The results show that HECs in the transition countries of Central and Eastern Europe differ from their western-European or U.S. counterparts with regard to these three aspects. HECs were established because of centrally imposed legal regulations. Little initiatives in this area were taken by medical professionals interested in resolving emerging ethical issues. HECs in the transition countries concentrate mostly on review of research protocols or resolution of administrative conflicts in healthcare institutions. Moreover, integration of non-professional third parties in the workings of HECs is often neglected. We argue that these differences can be attributed to the historical background and the role of medicine in these countries under the communist regime. Political and organizational structures of healthcare as well as education of healthcare staff during this period influenced current functioning of clinical ethics consultation in the transition countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

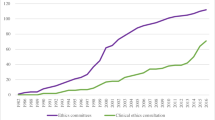

The development of Hospital Ethics Committees (HECs) reaches back to the 1970s when the first clinical ethics consultation structures were established in the United States (Goldner 2000). By 2007, all large U.S. hospitals had already established a process for ethics consultation (Fox et al. 2007). Although the start of similar developments in Western Europe (with the exception of the United Kingdom) has been delayed by almost two decades, the implementation of ethics committees in Western Europe is now a rapidly progressing process (Schochow et al. 2015; Schildman et al. 2010; Førde and Pedersen 2008; Guerrier 2006; Hope and Slowther 2000).

The establishment of HECs in the U.S. and Western Europe has mostly followed a bottom-up approach. The committees were created as a response to the value-laden nature of clinical decision-making (Aulisio and Arnold 2008). The aim of these committees is to provide education and advice for health care professionals, patients, their families and institutions regarding ethical questions, conflicts of values, and uncertainties that emerge in the healthcare setting (Tarzian et al. 2015; Andorno 2007). To fulfill this objective, HECs in the U.S. and Western Europe attempt to incorporate a wide professional spectrum of members and include representation from community members (Courtwrigth et al. 2014; Aulisio et al. 2000).

Parallel to the development of HECs in Western Europe, clinical ethics consultation recently became an element of the medical landscape in the transition countries of Central and Eastern Europe.Footnote 1 Their initial goal was to provide assistance in the “moral renewal” of medicine and national healthcare systems during the countries’ transition period towards becoming a democratic society (Glasa 2000a, 2004). “Moral renewal” in this context referred to deeper commitment to medico-ethical principles, i.e. patient autonomy.

Although the HECs of some of these countries have already been analyzed (Borovečki et al. 2006a; Czarkowski et al. 2015; Glasa 2000b; Glasa et al. 2013; Steinkamp et al. 2007), no study has attempted a comprehensive analysis of HECs in Central and Eastern Europe. Therefore, this research focused on examination of characteristics of these bodies in the international perspective under the following aspects: how HECs in the transition countries were established; what the character of consultation and area of responsibility of HECs in the transition countries are; and what the member composition of HECs in these countries looks like. We analyzed particular distinctions between HECs in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe and their Western European and U.S. counterparts and aimed at providing answers as to the reasons for such differences.

Methods and Materials

Methods

For the purpose of this analysis, a literature search of the PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science and BELIT databases was conducted. The goal of this search was to provide answers and empirical evidence for the preceding research questions. Due to the language skills of the researchers, sources in the English, German, and Polish languages were searched. In all three languages, the keywords “hospital ethics committee”, “clinical ethics committee”, “clinical ethics consultation”, and “clinical ethics” were searched in combination with the names of post-communist countries in Central and Eastern Europe. Countries included in the search were: Albania, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Kosovo, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, and Ukraine. For analysis, papers published since 1989 were selected, that is, the year in which most countries in Central and Eastern Europe entered the transition period towards democratic societies. 1294 records were identified through the literature search in the databases. After removal of duplicates, 227 abstracts were screened for relevance to the topic and the research questions. Following, 92 full-texts were examined considering the preceding research questions. Out of these 92 full-texts, 36 studies were included in the analysis. Criteria for the selection of studies were developed on the basis of the research questions and comprised: first, the specification of mode of establishment of HECs; second, the description of the character of consultation they provide; third, characterization of their composition. Drawing on the key findings from the analysis, we developed a narrative synthesis.

Materials

In the analysis of texts on HECs in the transition countries, both research and non-research manuscripts from peer-reviewed journals were included. Research manuscripts included quantitative analyses and qualitative research studies. Commentaries and case reports were acceptable non-research manuscripts. In addition, chapters in edited volumes on the topic were also included in the analysis. In total, materials for the analysis encompassed 25 research manuscripts, 6 chapters in edited volumes, 2 commentaries, and 3 country information reports published in the supplement “Ethics Support in Clinical Practice. Status Quo and Perspectives in Europe” to the 11th Issue of journal “Medical Ethics & Bioethics” (Glasa 2004). Papers included in the analysis are presented in Table 1.

Results

Mode of Establishment

HECs in most countries of Central and Eastern Europe were established on the basis of a top-down decision. They were formed as a result of binding legal regulations prescribing the organization of ethical consultation service. In several countries, an initial bottom-up approach towards establishment had to be reinforced through legal regulations. Alternatively, HECs were formed because of accreditation requirements (Table 2).

Development of HECs in Belarus was initiated on the central level of the Ministry of Health in 1998 with the formation of local bioethical committees (Vishneuskaya 2012). Similarly, HECs in all major Bulgarian hospitals were established on the basis of governmental Regulation N 14 in 2000 (Krastev 2011). In addition, the Law on Medicinal Products of 2007 prescribed creation of ethics committees in every medical institution conducting research. Following, 195 research ethics committees were officially registered in this country (Aleksandrova-Yankulovska 2017). Croatian HECs started to be organized after the implementation of the Law on Health Protection in 1997. The lack of earlier individual actions in this direction shows that the creation of these institutions was not a grassroots initiative but rather the effect of the bureaucratic behavior of hospital administrations (Borovečki et al. 2006a). The example of Hungary provides a certain distinction. Although medical ethics committees in this country were already established in the 1950s, their task did not include resolution of ethical questions. They only concentrated on the practice of bribery in healthcare (Blasszauer 1991). The role of these committees was defined anew in the Health Act of 1997. According to that Act, all medical directors of clinics and hospitals were obligated to establish a local ethics committee. Activities of these bodies should comprise support in controversially ethical cases and enforcement of patients’ rights (Blasszauer and Kismodi 2000). In Lithuania, in the course of the healthcare reform starting in the mid-1990s, HECs became mandatory for larger hospitals. The guidelines for the establishment of clinical ethics committees were issued by the Lithuanian Ministry of Health in 1997 (Steinkamp et al. 2007). The Serbian Federal Law of Organization of Health Institutions of 1990 put a requirement on every healthcare institution to establish an ethics committee. Yet, as a report from this country stated, even a decade later many hospitals had not attended to this duty (Maric and Tiosavljevic 2000; Omer 2004).

In Poland, the Act on Accreditation in Healthcare from 2008 regulated standards on resolving ethical issues in hospitals. According to this Act, one of the requirements for accreditation was establishing a group that could serve other employees and patients with advice on ethical issues. Previous to this date, only one ethics committee existed in Poland on a local level (Czarkowski 2010). In a survey among members of clinical ethics committees, the majority of responses cited accreditation requirements as the main reason for creating HECs (Czarkowski et al. 2015).

In the Czech and the Slovak Republics, the initial foundation of HECs can be described as a spontaneous and grassroots movement that occurred in the course of the moral revival connected to the “Velvet Revolution” of 1989. Yet, only a small number of these committees remained active in the following years (Šimek et al. 2000; Glasa et al. 2000). After the initial enthusiasm towards the creation of HECs, many of these institutions dissolved because of lack of obligatory regulations, scarce resources, and diminishing will to provide ethical services (Glasa et al. 2000). Therefore, a legal regulation was necessary. In the Czech Republic, the Drug Act No. 79 of 1997 confirmed the status of already existing committees and put an obligation to establish HECs in hospitals, in which ethical consultation was not provided (Šimek et al. 2010). In the Slovak Republic, the Law No. 576 of 2004 required all inpatient health care facilities to have ethics committees established to deal with ethical problems connected with health care provision (Steinkamp et al. 2007). Similar developments had been observed in Estonia; although HECs were spontaneously created in two large hospitals in 1997 (Tikk and Parve 2000), 7 years later no further HECs existed in this country (Talvik 2004).

Character of Provided Consultation

Research in this area points to a particular character of consultation provided by HECs in the transition countries (Table 3).

Responsibilities of HECs in the transition countries concentrate mostly on the evaluation of medical research and organizational issues. These tasks do not comply with the essential functions of these bodies. Reports from Croatia, the Slovak Republic, Bulgaria, and Slovenia show that the main task of HECs in these countries comprises the review and analysis of research protocols. Thus, other important functions of HECs are neglected. For example, 92% of cases of one Croatian HEC during the 1997–2007 period focused on the review of research protocols. Only 8% of the responsibilities related to difficult ethical cases, the development of guidelines or educational activities (Sorta-Bilajac Turina et al. 2014). Approximately only 12% of physicians and 3% of nurses in Croatia ever used a clinical ethics consultation service. Likewise, although guidelines of the Slovakian Ministry of Health mention consultation in ethically difficult cases as the main aim of HECs, in practice, committees in this country work mostly as research ethics committees (Glasa et al. 2013). They take part only occasionally in ethics consultations and in institutional policy development—another task assigned to these bodies through the guidelines of the Slovakian Ministry of Health (Glasa et al. 2000). Similarly, the main responsibility of clinical ethics committees in Slovenia lies within the area of assessing medical research (Voljč 2017). Other than this, little attention is paid to ethical issues emerging in clinical situations. Reports from Slovenia (Grosek et al. 2016; Groselj et al. 2014) and Bulgaria (Aleksandrova 2008) show a tendency among physicians towards avoiding consultation with clinical ethics committees.

In Poland, HEC’s opinions in difficult medical decisions, such as discontinuation of medical treatment, amount to only 12% of all consultations (Czarkowski et al. 2015). The majority of consultations concern ethical questions in organizational issues, such as conflicts among hospital employees or conflicts between hospital employees, patients and their families. Examples of common topics for consultation include thefts, division of responsibilities among physicians and nursing staff, conflicts between superiors and subordinates or smoking on the premises. Results of a study among intensive care physicians in this country revealed that only 28% find consultation with a HEC helpful in making an ethically difficult decision, such as limiting life-saving treatment (Kübler et al. 2011). A similar situation can be observed in Lithuania. The guidelines for medical ethics committees, issued by the Ministry of Health in 1997, list facilitation of the decision-making in controversial ethical cases as one of the major assignments (Steinkamp et al. 2007). Yet, in this country, the tasks of ethics committees mainly include resolving complaints about dishonest or inappropriate behavior of staff members (Bankauskaite and Jakusovaite 2006) or disciplinary actions against physicians (Steinkamp et al. 2007). In Romania, major ethical dilemmas concern the issues of economic constraints and underpayment, rather than cases that exceed the limits of regular procedures (Doaga 2004).

Composition of HECs

It has been observed that established ethics committees in the transition countries are characterized by limited diversity with regard to the professional background of their members. Members that are not medical professionals are underrepresented in these bodies (i.e. ethicists or patients). Older doctors are also over-represented (Borovečki et al. 2006b; Borovečki et al. 2010; Czarkowski et al. 2015).

A survey of HECs in Poland indicated that 73% of HECs consisted of four to eight members. Usually, the number of members in a committee is five people (Czarkowski et al. 2015). Mostly, members of HECs in Poland are physicians. Other professions represented are: nurses, clergy, lawyers, psychologists and the administrative hospital staff. However, the number of trained ethicists represented is surprisingly low. Only 2% of all surveyed ethics committees in Poland have an ethicist as a member.

Similarly, in Croatia, an overwhelming majority of committees consists of five members—a number that is prescribed by law as the minimal number of participants (Borovečki et al. 2006a). Multidisciplinarity of the membership in HECs in this country is relatively low. Beside three physicians, who are required by law to participate in the work of a committee, HECs consist of theologians, lawyers, and nurses. Between 1991 and 2003, no ethicist, patient representative or philosopher was a member of any of the Croatian ethics committees.

In Hungary, the Health Act of 1997 stipulates that each HEC should be comprised of 5–11 members who should be selected based on multidisciplinarity. Yet, in practice, this requirement is rarely fulfilled (Blasszauer and Kismodi 2000).

Discussion

Mode of Establishment

Transition countries of Central and Eastern Europe mostly share a similar history after 1945, as well as similar economic and social characteristics, and political goals of participation in international and European institutions. Transition towards this aim included not only the rediscovery but also the redefinition of societal values. Therefore, a natural course of action during the process of democratization was to introduce a process of ethical and moral revival in healthcare and medicine. One of the steps in this process was the establishment of HECs. Yet, a specific approach towards this aim is visible. The creation of clinical ethics committees in transition countries was mostly dominated by a top-down model. As such, central decision-making bodies, such as ministries, initiated organization of ethics consultation on the local level. Exceptions include the Czech Republic, Estonia, and the Slovak Republic, where creation of HECs were grassroots initiatives following the wave of democratization of these countries in the 1990s. In Poland, similar bottom-up initiatives existed, yet were rather rare (Czarkowski 2010). Although HECs in this country were established on the basis of initiatives in particular healthcare institutions, the main reason for their establishment was the accreditation requirements defined by law (Czarkowski et al. 2015).

Such an approach clearly differs from the bottom-up approach known from several non-transition countries. Aulisio and Arnold (2008) argue that HECs in the United States arose as a response of clinical professionals to the value-laden nature of clinical decision-making and uncertainties that occur in contemporary healthcare settings. Bottom-up initiatives were among the major impulses in this process. Similar developments could be observed in the United Kingdom (Slowther et al. 2004), the Netherlands (van der Kloot-Meijburg and Ter Meulen 2001), Norway (Førde and Pedersen 2008, 2011), and Germany and Italy (Fournier et al. 2009) where concurrent interests of clinical professionals and patients in resolving ethical conflicts provided a breeding ground for the establishment of HECs. For example, in Germany, the implementation of clinical ethics consultations began in 1995, well before the Central Ethics Commission of the German Medical Association (ZEKO) recommended the establishment of such institutions (Schochow et al. 2015). In France, the creation of HECs proceeded in two directions: top-down and bottom-up. In 1983, the French National Ethics Committee (CCNE) was established by political decision as a central advisory body. It actively promoted the creation of local ethics committees, which aim should primarily concentrate on the review of research protocols. In addition to this, various supplementary tasks were undertaken by these committees, such as provision of help in clinical practice and education. At the same time, several local initiatives have been carried out, mainly promoted by hospital healthcare providers interested in ethics and by growing social concerns about ethical issues. Even before the introduction of a regulation on “ethical reflection” in 2002, many hospitals had already had internal structures dedicated to clinical ethics. They functioned under various names and provided various ethical services (Guerrier 2006).

It has been argued that the top-down approach provides certain advantages. For example, this approach allows an institution to establish HRCs relatively fast (Steinkamp et al. 2007) and enables a transparent and systematic form of organization (Kovács 2010). On the other side, the top-down approach does not always mirror norms and values of health professionals. Moreover, creation of ethics committees in a top-down manner does not necessarily reflect interests of health professionals in for ethical guidance or their participation in such organization. In contrast, a bottom-up model, based on individual initiatives, provides better coherence with practical and professional values without influence of state or administration organs. In this model, stakeholders start with a “moral conflict at the bedside” and progressively develop organizational structures for resolution of ethical conflicts in the future (Kovács 2010).

When dealing with the centrally regulated creation of clinical ethics committees in transition countries, one must consider the historical organization of medicine under the communist dictatorships. During this period, healthcare was subordinated to central planning and politically motivated organizations (Weinerman 1968). Healthcare institutions were regarded as “health factories” (Borovečki et al. 2005). The evaluation of their work was based on the aim of the provision of a healthy workforce for the state’s economy. The number of beds, the amount of patients processed, the time of hospitalization or the level of technical sophistication were the crucial factors. Little, if any, attention was paid to ethical problems that arose in providing healthcare. Decisions about particular situations and their ethical implications were mostly forwarded to and taken by superiors (i.e. politically appointed heads of departments). Such an authoritative, top-down approach was one of the central attributes of medicine in these dictatorships. Hierarchical structures and highly legalistic frameworks of healthcare in the transitional countries are still the inheritance of the communist era (Jenkins and Klein 2005; Aleksandrova-Yankulovska 2017). Bureaucratic requirements dominate over personal judgments or ethical considerations of the healthcare professionals. The tendency to forward problems upwards in the professional hierarchy and the expectation for decisions provided by superiors along the centrally established guidelines is evident (Aleksandrova 2008). Although the creation of clinical ethics committees was sometimes enthusiastically supported by medical professionals, such initiatives were seldom taken at the lower levels of healthcare administration. The previously provided example of Estonia is a case in point. The reason for such a situation could be the underdevelopment of the democratic culture in the healthcare institutions, as well as an historically formed attitude to the concept of healthcare. European countries in transition share a similar approach to bioethics. In this approach, justice (i.e. patients’ rights in healthcare) is regarded as a gift granted by superiors, which prevents bottom-up initiatives to create independent institutions, such as HECs (Dickenson 1999). Rather, such initiatives are dictated on a national level and complemented by ministerial decrees and guidelines.

Character of Provided Consultation

It has been observed that HECs in the transition countries mostly provide consultation on ethical issues in research or on minor conflicts between hospital employees, patients and their families. Such situations clearly differ from the functions of HECs in the non-transition setting. Most HECs in Western European countries were established as mixed committees (Steinkamp et al. 2007). In this, they fulfilled the tasks of clinical ethics consultation and research ethics consultation. Yet, in due course, the allocation of tasks for these bodies changed. At the moment, the functions of HECs in Western European countries focus on the facilitation of ethical reflection, ethics consultation, and the establishment of policy guidelines (Schochow et al. 2017; Fournier et al. 2009). In this function, they clearly differ from Research Ethics Committees, which are independent bodies that concentrate on ensuring that medical research is designed in conformity to relevant ethical standards (Hedgecoe et al. 2006).

It is worth mentioning that although in several countries of Western Europe and in the United States case consultation is one of the stated primary aims of HECs, this function can nevertheless be rare or infrequent. In the United Kingdom, consultation in individual clinical cases rose from two requests a year in 2001 to six or more requests a year in 2010 (Slowther et al. 2012). In the United States, the median number of consults performed by ethics consultation services in 2006 was three (Fox et al. 2007), although this number can vary significantly across institutions (Courtwrigth et al. 2014; Watt et al. 2018; Robinson et al. 2017).

An important influence on the character of provided consultation through HECs in the transition countries is the protracted tradition of medical paternalism. This tendency is especially visible among the older healthcare staff. Here, the patterns of the paternalistic physician–patient relationship formed during the communist regime still continue (Barr 1996; Vishneuskaya 2012). In this period, the decisive criterion for quality of medical work was the scientific assessment of objective and subjective needs of the patients. This had to be taken by physicians and nurses. In accordance with the doctrine of Marxism–Leninism, the central ethical principle was the subordination of one’s own personal interests to those of the society. (Korotkikh 1989; Luther 1989; Prodanov 2001). As there were no programs of teaching of biomedical ethics, a large group of older physicians that currently take part in the works of HECs never had any formal education regarding modern approaches to ethics (Borovečki et al. 2006c). Processes of socialization and adherence to former ways of behavior play an important role. Therefore, the attitude of medical circles still centers around the old Hippocratic moral principle “Salus aegroti suprema lex” (“The well-being of the patient is the most important law”). For example, a survey among healthcare staff in Croatia revealed the dominance of the paternalistic approach (Borovečki et al. 2006a). The respondents would overrule a patient’s refusal of a treatment if they regarded such treatment as beneficial for the patient. Moreover, mentally ill patients are oftentimes regarded as incompetent. An examination of opinions of Hungarian intensive care physicians regarding the issue of limitation of resuscitation shows a similarly paternalistic approach (Elbo et al. 2005). Similar results are found in the study on non-treatment of children with Down Syndrome in Hungary (Hermann and Méhes 1996). Patients’ autonomy plays a secondary role in these cases. A similar study from Lithuania reveals that general practitioners do not always consider the personal values or lifestyles of patients (Bankauskaite and Jakusovaite 2006).

Such models of paternalistic medicine could affect the inclination to recognize ethical problems and the will to deal with them. Instead of an involvement in morally challenging ethical problems that could result in professional disadvantages, physicians tend to deal with relatively simple tasks related to research protocols and minor conflicts in the working place. In this, the role of contemporary HECs resembles the function of previous doctors’ committees charged with improving socialist morality in their institutions (Blasszauer and Kismodi 2000). Moral conflicts, when they occur, are seldom presented on the forum of organized ethical consultation. Rather, heads of the departments or colleagues are consulted (Aleksandrova 2010). The experience of older doctors is, in such cases, equated with competence in ethics. Such practice mirrors previous patterns of behavior in a hierarchically and centrally organized healthcare. An additional problem constitutes patients’ attitudes towards ethical consultation. There is little knowledge about the existence and services of HECs among the patients. Professional medical staff is regarded as the highest authority in all aspects of health and illness, including ethical ones. Patients are still missing specific information or education about possibilities of resolving clinical ethical problems that reach beyond the organizational or administrative issues of their treatment in a healthcare institution.

Composition of HECs

The number of HECs’ members in the transitional countries do not differ much from the average number of members in the non-transitional countries like, for example, the United States (Fox et al. 2007). Yet, the less diverse professional backgrounds among the members is notable. For example, in 2011, ethicists were represented in 16 of 31 Norwegian HECs (Førde and Pedersen 2008). In the United Kingdom, 60% of HECs had an academic ethicist as a member (Slowther et al. 2012).

One factor contributing to the limited diversity and number of HECs members in transition countries could be the heritage of the totalitarian past. During the communist regime, political actors imposed on medicine, among other tasks, an important position in disciplining the society in the spirit of the socialist ideology. Healthcare facilities often played a correctional role for non-conforming individuals. Examples of closed venereological wards in the German Democratic Republic, Polish Peoples’ Republic, and other communist countries distinctly show this role (Schochow and Steger 2016; Kempinska-Miroslawska and Wozniak-Kosek 2013). Similar examples are the closed psychiatric wards in the Soviet Union (Bonnie and Polubinskaya 1999; van Voren 2010). Instances of medical abuse were also reported in Romania (Thau and Popescu-Prahovara 1992). Individuals behaving in a way that was against ideologically accepted conduct were often compulsorily committed to such institutions. This occurred without regard to their actual medical need, consent or information about the aim and procedure of their hospitalization. In such “correctional” healthcare facilities, medical professionals played the decisive role. Often, through their actions, they shaped the operations of healthcare institutions and imposed their own standards on the victims. Medical care had the educative goal of transforming individuals into “socialist personalities”.

From the point of analysis of HECs in transition countries, medical transgressions in earlier periods could have an influence on the character and composition of HECs. In part, they can provide an explanation for why non-professional third parties are oftentimes neglected in the ethics consultation. Such exclusion mirrors the past view of medicine as a closed network in which the dominating role is reserved for professional medical staff. Decisions in this system were made by a few privileged individuals—in this case high-ranking medical professionals—and possibilities of public debate and public control were considerably diminished. In case of lacking mandatory recommendations for inclusion of other professions in the work of a HEC, these institutions tend to have limited diversity of the members, consisting mostly of medical professionals. On the other hand, previous non-ethical behavior and transgressions of medical professionals against the patients could incline towards exclusion of outside parties—especially ethicists—from participation in HECs. Ethical considerations in such contexts, based on democratic principles of wide participation and consent, could be associated with the apprehension that previous transgressions will be revealed and litigated.

An additional aspect influencing the limited professional diversity of participants in HECs in the transition countries could be the specific role and the field of activity of these bodies. HECs in most analyzed countries show characteristics of mixed institutions with responsibilities focused on the review of research protocols. Consequently, members of HECs would be recruited with a focus on their specific knowledge and competencies in medical research and scientific methods. Yet, it has been observed that Research Ethics Committees in non-transitional countries are characterized by a multidisciplinary background of their members. Diversity of membership with regard to position, education, professional experience, and gender is required in several non-transitional countries (Hemminki 2016; Hedgecoe et al. 2006; Edwards et al. 2007).

A further factor explaining the professional background characteristics and number of members in HECs in the transition countries could be connected to insufficient motivation of the affiliates. The argument for adequate remuneration for members of these and similar bodies can be found in the literature (Druml et al. 2009). The work in a HEC is mostly an additional activity for the majority of the members, and often involves an additional contribution of time. Therefore, a financial remuneration could provide a decisive factor for participation. The lack of such remuneration can cause difficulties in recruiting highly qualified professionals.

Limitations

The limitations of this study lie in the character of information provided by analyzed sources. Descriptions of HECs in countries of Central and Eastern Europe often concentrate only on particular aspects. In addition, not all countries are covered by the available sources. Further constraint is based on the language limitations. Due to the language skills of the researchers, only articles published in English, German, and Polish were evaluated and analyzed. Additional research on the topic could cover articles in national languages of the transition countries. Such comprehensive research into all aspects of HECs in these countries and their contemporary attributes could provide a full description of their establishment, scope of activities, and composition. However, the results yield important insights into the features of these institutions and the ways in which they are distinct from their Western European or U.S. counterparts.

Conclusions

Contention between centrally dictated aims of medicine and its individual moral obligations often lead to conflicts that affect functioning of ethical healthcare consultation. Such contention is especially visible in the states in transition from autocratic regimes to democratic society. The development of civil societies after the fall of communist systems led to the process of institutionalization of clinical ethics consultation. In its aim, this process should provide medical personnel and patients with an instrument to resolve ethical problems and to encourage ethical professional behavior. Right now, hospital or clinic ethics committees exist in most post-communist countries. However, their creation and mode of functioning still mirrors some past patterns of medicine under non-democratic regimes. HECs were mostly established on grounds of central legal regulations. Few initiatives in this area were taken by medical professionals interested in resolving emerging ethical issues. The tendency for forwarding problems upwards in the professional hierarchy and expectation for decisions provided by superiors along the centrally established guidelines is evident. HECs in the transition countries concentrate mostly on the review of research protocols or the resolution of administrative conflicts in healthcare institutions. Moreover, non-professional third parties are hardly integrated in the workings of HECs. Such patterns can be explained through hierarchical structures that still dominate in healthcare institutions, the highly legalistic framework of healthcare in the transitional countries, continuing paternalistic attitudes towards patients, and the heritage of the disciplining role of medicine in the past.

Up to now, the topic of HECs in the transition countries has not been an object of systematic analysis. Further research in this area should concentrate on the provision of detailed information about the mode of establishment of HECs, character of consultation they provide, and their composition, i.e. through interviews with the members of these committees or questionnaires addressed to the hosting institutions.

As the literature on the topic is often dated, further research could provide a present-day picture of clinical ethics consultation in the countries under investigation. Especially interesting in this context would be the influence of the political and cultural developments within societies on the state of the process of consultation. Questions of democratic regress that is observable in several Central and Eastern European Countries nowadays could significantly impact future development of medical ethics in this region. The proper functioning of clinical ethics consultation requires a political setting that is based on democratic values and includes transparent institutions and respect for patients’ rights. Grassroots movements and initiatives of patients could play an important and special role here. Through highlighting the controversial issues and through their influence on legislation processes, patients’ civil movements could influence the way in which Hospital Ethics Committees function and their further development.

Notes

For the following study, we define transition countries of Central and Eastern Europe as countries that after 1989 initiated a set of political, structural and social transformations from one-party, central rule towards democratic and pluralist political systems, with the aim of participation in the international and European institutions.

References

Aleksandrova, S. (2008). Survey on the experience in ethical decision-making and attitude of Pleven University Hospital physicians towards ethics consultation. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy,11(1), 35–42.

Aleksandrova, S. (2010). Experience in ethical decision-making and attitudes towards ethics consultation of regional hospital physicians in Bulgaria. In J. Schildman, J. Gordon, & J. Vollman (Eds.), Clinical ethics consultation. Theories and methods, implementation, evaluation (pp. 176–187). Farnham, Burlington: Ashgate.

Aleksandrova-Yankulovska, S. (2017). Development of bioethics and clinical ethics in Bulgaria. Folia Medica,59(1), 98–105.

Andorno, R. (2007). Global bioethics at UNESCO: In defense of the universal declaration on bioethics and human rights. Journal of Medical Ethics,33(3), 150–154.

Aulisio, M. P., & Arnold, R. M. (2008). Role of the ethics committee: Helping to address value conflicts or uncertainties. Chest,134(2), 417–424.

Aulisio, M. P., Arnold, R. M., & Younger, S. J. (2000). Health care ethics consultation: Nature, goals, and competencies. A position paper from the society for health and human values—Society for bioethics consultation task force on standards for bioethics consultation. Annals of Internal Medicine,133(1), 59–69.

Bankauskaite, V., & Jakusovaite, I. (2006). Dealing with ethical problems in the healthcare system in Lithuania: Achievements and challenges. Journal of Medical Ethics,32(10), 584–587.

Barr, D. A. (1996). The ethics of Soviet medical practice: Behaviors and attitudes of physicians in Soviet Estonia. Journal of Medical Ethics,22(1), 33–40.

Blasszauer, B. (1991). Medical ethics committees in Hungary. HEC Forum,3(5), 277–283.

Blasszauer, B., & Kismodi, E. (2000). Ethics committees in Hungary. In J. Glasa (Ed.), Ethics committees in Central and Eastern Europe (pp. 191–196). Bratislava: Charis.

Bonnie, R. J., & Polubinskaya, S. V. (1999). Unraveling soviet psychiatry. Journal of Contemporary Legal Issues,10, 279–298.

Borovečki, A., Makar-Aušperger, K., Francetić, I., Babić-Bosnac, A., Gordijn, B., Steinkamp, N., et al. (2010). Developing a model of healthcare ethics support in Croatia. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics,19(3), 395–401.

Borovečki, A., ten Have, H., & Oresković, S. (2005). Ethics and the structures of health care in the European countries in transition: Hospital ethics committees in Croatia. British Medical Journal,331(7510), 227–229.

Borovečki, A., ten Have, H., & Oresković, S. (2006a). Education of ethics committee members: Experiences from Croatia. Journal of Medical Ethics,32(3), 138–142.

Borovečki, A., ten Have, H., & Oresković, S. (2006b). Ethics committees in Croatia in the healthcare institutions. The first study about their structure and functions, and some reflections on the major issues and problems. HEC Forum,18(1), 49–60.

Borovečki, A., ten Have, H., & Oresković, S. (2006c). Ethics and the European countries in transition—Past and the future. Bulletin of Medical Ethics,214, 15–20.

Courtwrigth, A., Brackett, S., Cist, A., Cremens, M. C., Krakauer, E. L., & Robinson, E. M. (2014). The changing composition of a hospital ethics committee: A Tertiary Care Center’s experience. HEC Forum,26(1), 59–68.

Czarkowski, M. (2010). Jak zakładać szpitalne komisje etyczne? Polski Merkurjusz Lekarski,28, 207–210.

Czarkowski, M., Kaczmarczyk, K., & Szymańska, B. (2015). Hospital ethics committees in Poland. Science and Engineering Ethics,21(6), 1525–1535.

Dickenson, D. L. (1999). Cross-cultural issues in European bioethics. Bioethics,13(3–4), 249–255.

Doaga, O. (2004). Romania. Medical Ethics & Bioethics,11(issue supplement 1), 17–18.

Druml, C., Wolzt, M., Pleiner, J., & Singer, E. (2009). Research ethics committees in Europe: Trials and tribulations. Intensive Care Medicine,35(9), 1636–1640.

Edwards, S. J. L., Stone, T., & Swift, T. (2007). Differences between research ethics committees. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care,23(1), 17–23.

Elbo, G., Diószeghy, C., Dobos, M., & Andorka, M. (2005). Ethical considerations behind the limitation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in Hungary—The role of education and training. Resuscitation,64(1), 71–77.

Førde, R., & Pedersen, R. (2008). Clinicians’ evaluation of clinical ethics consultations in Norway: A qualitative study. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy,11(1), 17–25.

Førde, R., & Pedersen, R. (2011). Clinical ethics committees in Norway: What do they do, and does it make a difference? Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics,20(3), 389–395.

Fournier, V., Rari, E., Førde, R., Neitzke, G., Pegoraro, R., & Newson, A. J. (2009). Clinical ethics consultation in Europe: A comparative and ethical review of the role of patients. Clinical Ethics,4(3), 131–138.

Fox, E., Myers, S., & Pearlman, R. A. (2007). Ethics consultation in United States hospitals: A national survey. American Journal of Bioethics,7(2), 13–25.

Glasa, J. (2000a). Ethics committees [HECs/IRBs] and healthcare reform in the Slovak Republic: 1990–2000. HEC Forum,12(4), 358–366.

Glasa, J. (Ed.). (2000b). Ethics committees in Central and Eastern Europe. Bratislava: Charis.

Glasa, J. (2004). Ethics support in clinical practice. Status quo and perspectives in Europe. Medical Ethics & Bioethics,11(1), 1–23.

Glasa, J., Bielik, J., Ďačok, J., Glasová, M., & Porubský, J. (2000). Ethics committees in the Slovak Republic. In J. Glasa (Ed.), Ethics committees in Central and Eastern Europe (pp. 229–238). Bratislava: Charis.

Glasa, J., Krčméryová, T., Glasová, H., & Glasová, M. (2013). Clinical ethics committees in Slovakia—present situation and perspectives. Revista Româna de Bioeticǎ,11(3), 123–129.

Goldner, J. A. (2000). Institutional review boards and hospital ethics committees in the United States. In J. Glasa (Ed.), Ethics committees in Central and Eastern Europe (pp. 251–264). Bratislava: Charis.

Grosek, S., Orazem, M., Kanic, M., Vidmar, G., & Groselj, U. (2016). Attitudes of Slovene pediatricians to end-of-life care. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health,52(3), 278–283.

Groselj, U., Orazem, M., Kanic, M., Vidmar, G., & Grosek, S. (2014). Experience of the ICU Slovene physicians with end-of-life decision making: A nation-wide survey. Medical Science Monitor,20, 2007–2012.

Guerrier, M. (2006). Hospital based ethics, current situation in France: Between “Espaces” and committees. Journal of Medical Ethics,32(9), 503–506.

Hedgecoe, A., Carvalho, F., Lobmayer, P., & Raka, F. (2006). Research ethics committees in Europe: Implementing the directive, respecting diversity. Journal of Medical Ethics,32(8), 483–486.

Hemminki, E. (2016). Research ethics committees in the regulation of clinical research: Comparison of Finnland to England, Canada, and the United States. Health Research Policy and Systems. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-016-0078-3.

Hermann, R., & Méhes, K. (1996). Physicians’ attitudes regarding down syndrome. Journal of Child Neurology,11(1), 66–69.

Hope, T., & Slowther, A. (2000). Clinical ethics committees: They can change clinical practice but need evaluation. British Medical Journal,321(7262), 649–650.

Jenkins, R., & Klein, J. (2005). Mental health in post-communist countries. The results of demonstration projects now need implementing. British Medical Journal,331(7510), 173–174.

Kempińska-Mirosławska, B., & Woźniak-Kosek, A. (2013). Health policy regarding the fight against veneral diseases in Poland in the years 1945–1958. Military Pharmacy and Medicine,6(4), 49–72.

Korotkikh, R. V. (1989). Medical ethics: Problems of theory and practice. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy,14(3), 269–282.

Kovács, L. (2010). Implementation of clinical ethics consultation in conflict with professional conscience? Suggestions for reconciliation. In J. Schildman, J. Gordon, & J. Vollman (Eds.), Clinical ethics consultation. Theories and methods, implementation, evaluation (pp. 65–78). Farnham, Burlington: Ashgate.

Krastev, Y. (2011). Institutionalisation of Bulgarian ethics committees: History and current status. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics,8(3), 148–151.

Kübler, A., Adamik, B., Lipinska-Gediga, M., Kedziora, J., & Strozecki, Ł. (2011). End-of-life attitudes of intensive care physicians in Poland: Results of a national survey. Intensive Care Medicine,37(8), 1290–1296.

Luther, E. (1989). Medical ethics in the German Democratic Republic. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy,14(3), 289–299.

Maric, J., & Tiosavljevic, D. (2000). Ethics committees in Yugoslavia. In J. Glasa (Ed.), Ethics committees in Central and Eastern Europe (pp. 265–266). Bratislava: Charis.

Omer, A. (2004). Serbia and Montenegro. Medical Ethics & Bioethics,11(issue supplement 1), 19.

Prodanov, V. (2001). Bioethics in Eastern Europe: A difficult birth. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics,10(1), 53–61.

Robinson, E. M., Cadge, W., Erler, K., Brackett, S., Bandini, J., Cist, A., et al. (2017). Structure, operation, and experience of clinical ethics consultation 2007–2013: A report from the Massachusetts General Hospital Optimum Care Committee. The Journal of Clinical Ethics,28(2), 137–152.

Schildman, J., Gordon, J., & Vollman, J. (2010). Introduction. In J. Schildman, J. Gordon, & J. Vollman (Eds.), Clinical ethics consultation. Theories and methods, implementation, evaluation (pp. 1–7). Farnham, Burlington: Ashgate.

Schochow, M., Rubeis, G., & Steger, F. (2017). The application of standards and recommendations to clinical ethics consultation in practice: An evaluation at German Hospitals. Science and Engineering Ethics,23(3), 793–799.

Schochow, M., Schnell, D., & Steger, F. (2015). Implementation of clinical ethics consultation in German Hospitals. Science and Engineering Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-015-9709-2.

Schochow, M., & Steger, F. (2016). Closed venerology wards in the GDR. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venerology,30(10), 1814–1818.

Šimek, J., Šilhanová, J., & Vrbatová, I. (2000). Ethics committees in the Czech Republic. In J. Glasa (Ed.), Ethics committees in Central and Eastern Europe (pp. 169–172). Bratislava: Charis.

Šimek, J., Zamykalova, L., & Mesanyova, M. (2010). Ethics committee or community? Examining the identity of Czech Ethics Committees in the period of transition. Journal of Medical Ethics,36(9), 548–552.

Slowther, A. M., Johnston, C., Goodall, J., & Hope, T. (2004). Development of clinical ethics committees. British Medical Journal,328(7445), 950–952.

Slowther, A. M., McClimans, L., & Price, C. (2012). Development of clinical services in the UK: A national survey. Journal of Medical Ethics,38(4), 210–214.

Sorta-Bilajac Turina, I., Brkljačic, M., Čengić, T., Ratz, A., Rotim, A., & Bašić Kes, V. (2014). Clinical ethics in Croatia: An overview of education, services and research (an appeal for change). Acta Clinica Croatica,53(2), 166–175.

Steinkamp, N., Gordijin, B., Borovečki, A., Gefenas, E., Glasa, J., Gurrier, M., et al. (2007). Regulation of healthcare ethics committees in Europe. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy,10(4), 461–475.

Talvik, T. (2004). Estonia. Medical Ethics & Bioethics,11(issue supplement 1), 15–16.

Tarzian, A. J., Wocial, L. D., & The ASBH Clinical Ethics Consultation Affaires Committee. (2015). A code of ethics for health care ethics consultants. Journey to the present and implications for the field. The American Journal of Bioethics,15(5), 38–51.

Thau, C., & Popescu-Prahovara, A. (1992). Romanian psychiatry in turmoil. Bulletin of Medical Ethics,78, 13–16.

Tikk, A., & Parve, V. (2000). Ethics committees in Estonia. In J. Glasa (Ed.), Ethics committees in Central and Eastern Europe (pp. 173–178). Bratislava: Charis.

van der Kloot-Meijburg, H. H., & Ter Meulen, R. H. J. (2001). Developing standards for institutional ethics committees: Lessons from the Netherlands. Journal of Medical Ethics,27(issue supplement 1), 36–40.

van Voren, R. (2010). Political abuse of psychiatry—An historical overview. Schizophrenia Bulletin,36(1), 33–35.

Vishneuskaya, Y. A. (2012). Analysis and critical review of the development of bioethics in Belarus. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy,15(4), 365–371.

Voljč, B. (2017). Jurisdiction of the medical ethics committees. Zdravstveno Varstvo,56(4), 193–195.

Watt, K., Kirschen, M. P., & Friedlander, J. A. (2018). Evaluating the inpatient pediatric ethical consultation service. Hospital Pediatrics,8(3), 157–161.

Weinerman, E. R. (1968). The organization of health services in Eastern Europe. Report of a study in Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland, Spring, 1967. Medical Care,6(4), 267–279.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Orzechowski, M., Schochow, M. & Steger, F. Clinical Ethics Consultation in the Transition Countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Sci Eng Ethics 26, 833–850 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-019-00141-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-019-00141-z