Abstract

Purpose of review

The goal of the current review is to provide an update on the management of agitation in persons with dementia with a focus on pharmacological management of persons with Alzheimer’s disease.

Recent findings

As consistently effective and safe pharmacologic interventions are still lacking, identifying and addressing medical and environmental precipitants remain a priority. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine should be initiated to enhance cognition, and if present, management of insomnia or sundowning with trazodone is indicated. If agitation persists, treatment with citalopram can be initiated with attention paid to potential prolongation of the QT interval. Treatment with low doses of atypical antipsychotics such as risperidone or quetiapine can be effective after appropriate consideration of and disclosure of potential adverse effects.

Summary

In light of the lack of consistently effective treatments for agitation in dementia, there have been renewed efforts to define the condition and improve the design of trials of medications to treat it. Considering the heterogeneity of patients and their comorbidities as well as the specific nature of their “agitation”, there is no “one-size fits all” approach to agitation in AD. However, many options exist that can be prudently pursued for this common problem in this delicate population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Associated with advancing neurodegenerative disease, agitation is arguably the most disrupting and challenging symptom to patients, family members, and professional and non-professional caregivers. Despite its importance, currently available pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions have limited and unreliable efficacy. Barriers to the development of effective treatments include but are not limited to difficulties defining and measuring agitation in dementia, appropriate design of clinical trials, the frailty of the intended population, and perhaps the fundamental intractability of the problem.

Agitation is difficult to define as the term is used to include such diverse behaviors as wandering, targeted aggression, random striking out, disruptive vocalizations, or uncooperativeness. In light of this, the International Psychogeriatric Association convened a panel of experts with the goal of establishing principles guiding the definition of agitation in elderly populations [1••]. They ultimately defined agitation as [1] occurring in patients with cognitive impairment or a dementia syndrome; [2] exhibiting behavior consistent with emotional distress; [3] manifesting excessive motor activity, verbal aggression, or physical aggression; and [4] evidencing behaviors that cause excess disability and are not solely attributable to another disorder (psychiatric, medical, or substance-related). At its core, the International Psychogeriatric Association (IPA) definition of agitation consists of excessive motor activity defined by pacing, rocking, gesturing, pointing fingers, restlessness, performing repetitive mannerisms; verbal aggression typically exemplified as yelling, speaking excessively loudly, using profanity, screaming, shouting; and physical aggression mainly involving hurting others, grabbing, shoving, pushing, resisting, hitting, kicking, scratching, biting, throwing, slamming doors, tearing things, and destroying property. Absent from the IPA definition of agitation is the substantial delusional behavior that is highly prevalent in people with dementia. These typically consist of delusions of theft, paranoia, abandonment, and infidelity, that one’s spouse is an imposter; or one’s house is not one’s home. Agitation and delusions frequently co-occur and often are not distinguished.

The heterogeneity in the definition of agitation is reflected in the instruments used to measure it, and therefore its prevalence varies among studies. The Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) reflects the IPA’s definition and surveys 29 specific problematic behaviors, divided into Physical Aggressive and Non-Aggressive and Verbal Aggressive and Non-Aggressive behaviors [2]. The BEHAVE-AD scale elicits the frequency and severity of specific symptoms of agitation, i.e., verbal outbursts, physical threats, or violence, but not others [3]. A commonly used measure, the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) [4] and variants (including a short version [5] and a nursing home version [6]), was derived from the BEHAVE-AD and uses a screening question for each of 10 or 12 domains which, if endorsed, leads to questions eliciting specific symptoms within that domain. Its agitation/aggression domain includes resistance toward caregivers, uncooperativeness, stubbornness, being “hard to handle,” cursing, and kicking or hitting people and objects.

As a result of the heterogeneity of measures of agitation in dementia, overall or composite measures are of limited value for describing patients with agitation for clinical trials or in assessing beneficial effects from therapeutic interventions [7]. As the specific character of agitated behaviors change over the course of dementia and in response to environmental manipulation and psychosocial and medication treatment approaches, attention must be paid to how they are specifically measured in both clinical care and when interpreting research studies.

Despite a large number of randomized controlled clinical trials of medications for agitation and psychosis in dementia, only a few trials have demonstrated efficacy for specific pharmacological interventions. It has been argued that trial designs are frequently sub-optimal, and therefore some consideration has been given to improving them. Among the suggestions of a consensus panel discussing trial methods [8•] were [1] decreased emphasis on endpoint analyses and rather a focus on the trajectory of response over time, [2] appropriate selection of subjects with persistent, challenging agitation, [3] pre-specification of meaningful effect sizes and defining response in terms of numbers needed to treat, and [4] increased attention in trials to adverse effects in the frail population including sedation, decreased mobility, and cardio- and cerebrovascular events. In addition to methodological considerations however, it is also the case that current medications are of limited efficacy for either agitation or psychosis in the context of dementia.

In a recent population-based study of electronic health records of persons in the USA with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or dementia (excluding those with non-AD dementia) using the IPA definition of agitation as described above, an overall prevalence of 44.6% was found which was higher in moderate to severe stages (74.6%) [9]. In this paper, we will review evidence for chronic treatments (as opposed to prn use for acute agitation) of this common problem with a focus on available pharmacological treatments in AD. We will include a discussion of Lewy body disease (LBD) but will not focus specifically on frontotemporal dementia due to its heterogeneity or to vascular dementia in light of its frequent overlap with AD pathology [10].

Non-pharmacological interventions

Though the focus of this review is on pharmacological interventions for agitation in persons with dementia, non-pharmacological interventions should be considered prior to initiating drug therapy. The first step in the approach to the agitated dementia patient should be to evaluate for the presence of precipitating factors, both medical and environmental. Any sort of physical or emotional discomfort can lead to agitation in persons who cannot otherwise express their state of mind. A recent study reported that 23% of hospitalizations in cognitively impaired and unimpaired persons 70 years of age or greater were due to “ambulatory care-sensitive conditions” and therefore preventable [11]. Although not all admissions were due to agitation, agitation was common during hospitalization, emphasizing the importance of preventing, identifying, and treating agitation on an outpatient basis. In this population, particular attention should be given to infections (e.g., urinary tract and respiratory), cardio- and cerebrovascular disease, and medication effects, particularly when the agitation is of acute or subacute onset.

Situational factors frequently are antecedent to or exacerbate agitation and addressing them can lead to substantial benefits. Breaks in routine such as a move to an unfamiliar environment are common precipitants of agitation, and every attempt should be made to surround the patient with recognizable persons and belongings such as family photos and other possessions. A patient with dementia may have known or unknown aversions to specific persons or caregivers who, for example, might remind them of prior traumatic experiences (e.g., professional male caregivers for a woman who has previously been sexually assaulted). The presentation of familiar, individualized music can have an activating or soothing effect [12], and though one meta-analysis found a significant effect on improving agitation [13], a recent Cochrane review did not [14]. Structured holistic approaches [15, 16] in which communication training and person-centered care, physical activity programs, pet therapy (and even robot pet therapy [17]), massage, aromatherapy, and music therapy are combined might be helpful in improving quality of life and decreasing agitation [18].

Agitation can be particularly problematic at night when the potential for injury is greatest and when caregivers, both professional and unpaid, require sleep. The disruption of circadian rhythm is essentially ubiquitous in dementia, and specific attention to agitation occurring in the evening, or “sundowning”, is essential. In this context, normalization of the day-night light and dark cycle should be maintained and pharmacotherapy will be discussed below [19].

Pharmacological interventions

As previously discussed, we are currently lacking pharmacological interventions that reliably and safely decrease agitation in AD and dementia. No drugs are approved by the FDA for the treatment of agitation in dementia and in the European Union; only risperidone is approved for use in severe agitation. In the discussion below, we will attempt to outline the current literature and propose a framework for approaching patients with significant agitation refractory to non-pharmacological interventions with a focus on AD.

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AchE-Is), the first anti-dementia agents to demonstrate efficacy, were approved for marketing based on their effects on cognition and activities of daily living. They were developed on the basis of the recognized deficiency of cholinergic systems in AD which might underlie behavioral symptoms as well as the deficits in memory and attention. The results of studies of their efficacy in treating agitation and other behavioral disturbances in AD are uncertain [20,21,22,23,24,25]. They are not effective when they are initiated as a treatment for patients with agitation. However, post hoc subset analyses indicate that agitation and other problematic behaviors in patients with moderate to severe dementia that occur over the course of treatment are mitigated by AchE-Is compared with placebo. It should be noted however that agitation, itself, can sometimes occur as an adverse reaction to AchE-Is. As a standard of care for cognitive enhancement, they can be considered for most patients with dementia and might be helpful for associated agitation. However, they should not be considered as primary therapy for agitation in AD.

Memantine

This non-competitive NMDA antagonist is marketed for the treatment of moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease based on its effects on improving cognition, basic activities of daily living, and clinical global function. Importantly, although it is commonly used in patients with mild dementia or mild cognitive impairment, it is not effective in mild disease, and the FDA explicitly declined to provide marketing approval in this context. As agitation is somewhat more prevalent in people with more severe dementia, memantine might be expected to be helpful in this regard as well. However, although somewhat fewer, memantine-treated patients in clinical trials experience agitation as an adverse event; there is no trial evidence suggesting that memantine is beneficial as a treatment for patients who have agitation [26, 27].

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

Soon after SSRIs were introduced to for depression in the 1990s, they were studied for dementia, based on their safety and the association of serotoninergic deficits with depression and agitation [28]. Their utility in agitation and depression in dementia has been pursued in several clinical trials [29,30,31]. In general, SSRIs including citalopram and sertraline have not been effective for depression in dementia [32]. Sertraline did not show efficacy for agitation (defined by a total NPI score greater or equal to 5) in a trial in which patients had been treated with donepezil for 12 weeks prior to being randomized [33]. Citalopram, however, showed efficacy for agitation in a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study in which citalopram at 30 mg/day or placebo was added to background psychosocial support. There was a positive effect on the Neurobehavioral Rating Scale, agitation subscale (NBRS-A); a higher proportion of participants (40% vs 26%) showed moderate or marked improvement on a global change scale (the Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGIC)) and showed significant improvement on the CMAI [34•]. Worsening in cognition, QT interval prolongation, anorexia, and fever were also seen in the citalopram group. Citalopram at 30 mg/day is therefore not indicated for older persons because of the potential for cardiotoxicity. A post hoc, multivariate, unbiased subgroup analysis showed that dementia patients with moderate agitation and relatively less cognitive impairment (i.e., MMSE > 20) were more likely to benefit from citalopram than those with more severe agitation and greater cognitive impairment who were at greater risk for adverse responses [35]. Citalopram is a mixture of (R) and (S) enantiomers, and a subsequent pharmacokinetic study of data from this study showed an association of the plasma concentration of the (R) enantiomer with adverse effects and of the (S) enantiomer with improvement on the CGIC. A study of the (S) enantiomer (escitalopram) in agitation in AD is currently underway (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03108846).

Dopamine receptor-blocking agents

Conventional and atypical antipsychotics have been the most widely used medications to treat both delusions and agitation in people with dementia. Their use in dementia patients extended from their efficacy in treating psychosis in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. An early meta-analysis of typical neuroleptics confirmed a modest effect size (18%) with the authors emphasizing that 18 out of 100 treated patients received a benefit relative to placebo [36]. No difference was identified among haloperidol, thioridazine, and the comparison antipsychotics.

Considering the significant extrapyramidal effects of most conventional or first-generation antipsychotics, when antipsychotics with lower affinity for D2 dopamine receptors and antagonism for the post-synaptic 5-HT2 receptor subtype became available (“atypical antipsychotics”), their efficacy in dementia patients with agitation and delusions was assessed. In one study, risperidone at a mean dose of 1.1 mg/day led to a greater response than placebo on the total BEHAVE-AD score without substantial extrapyramidal effects [37]. A meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled studies of aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone for agitation, delusions, and aggression revealed some evidence of efficacy for risperidone and aripiprazole [38]. Common adverse effects included somnolence and urinary tract infection or incontinence in general and with extrapyramidal symptoms and abnormal gait with risperidone and olanzapine. As with typical antipsychotics, the overall average treatment effect size was found to be around 18%.

An NIH-funded study, the Clinical Antipsychotic Trial of Intervention Effectiveness-Alzheimer Disease (CATIE-AD) study, compared the efficacy and tolerability of risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine to placebo in AD patients with psychosis, aggression, or agitation. The study and outcomes were designed to better mirror clinical practice than most randomized clinical trials. Doses were adjusted depending on response and discontinuations due to adverse effects occurred in 18% (risperidone), 24% (olanzapine), 16% (quetiapine), and 5% (placebo) with there being no differences in the time to discontinuation due to lack of efficacy, a primary outcome of the study. As there were also no differences between treated groups in the CGIC, it was concluded that adverse effects on average offset the advantages of treatment with these medications [39••]. When efficacy measures were compared across groups at the end of the treatment, some benefits in anger, aggression, and paranoid ideation were seen with risperidone and olanzapine though worsened overall function was seen with olanzapine [40]. Further cost-benefit analysis revealed a superiority of placebo [41]. It should be concluded that no atypical antipsychotic is demonstrably more effective and that adverse effects are common. Treatment therefore needs to be individualized and should be reserved for those with severe agitation.

In 2005, based on a review of 15 placebo-controlled studies of atypical antipsychotics in which patients were treated for durations of generally 10 to 12 weeks, a 54% increase in death among persons receiving atypical antipsychotics was observed (3.5% vs 2.3%) [42]. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a public health advisory and black box warnings emphasizing the increased risk for death and that no antipsychotic is approved for the treatment of behavioral disturbances in elderly patients with dementia. The increased mortality may be due to cardiovascular, metabolic effects or increased susceptibility to infection. In light of this, treatment with antipsychotics for agitated patients with dementia should be avoided if possible. If the decision is made to treat a patient with dementia with antipsychotics, then the lowest dose of risperidone, 0.25 to .5 mg, or of quetiapine, 12.5 to 25 mg, should be initiated. Because of its metabolic effects, olanzapine should not be used for agitation in dementia.

Other marketed antipsychotics that have been considered for agitation and psychosis in dementia include aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and pimavanserin. Aripiprazole showed inconsistently positive outcomes in three trials in both nursing homes and the community for dementia patients with delusions [43, 44]. Effect sizes were small and adverse events limiting. Brexpiprazole is indicated for schizophrenia and as adjunctive therapy to antidepressants for major depression. It was not shown to be effective in two-phase three trials for agitation in dementia.

Pimavanserin, a 5-HT2A antagonist indicated for hallucinations and delusions associated with Parkinson’s disease, has been studied in three trials for agitation or psychosis in dementia; all of which were essentially negative [45]. There is an ongoing randomized discontinuation trial that might clarify its use for agitation. In summary, the efficacy and safety of pimavanserin for agitation or psychosis in dementia has yet to be demonstrated. As with other antipsychotics, it carries a black box warning for increased mortality in dementia and is associated with QT prolongation, peripheral edema, and confusion.

Lewy body disease

An important consideration in managing agitation in patients with dementia is the high prevalence of Lewy body pathology (LBP). Approximately 25% of patients with AD pathology have comorbid LBP [46], and in an autopsy series of patients with LBP, 51% had intermediate or high levels of AD pathology [47]. In light of the well-documented adverse effects of typical [48] and, to a lesser extent, atypical neuroleptics [49, 50] of worsening Parkinsonism and even precipitating neuroleptic malignant syndrome in LB disease, it is important to consider the possibility of its presence in the agitated dementia patient. As we currently lack an adequate biomarker for the presence of LBP, its presence is best inferred by the existence of characteristic clinical features of LBP (e.g., Parkinsonism, dream enactment behavior, visual hallucinations, fluctuating levels of attention). Treatment with neuroleptics should therefore be avoided in the agitated dementia patient with these symptoms. The only potential exception to this is the use of clozapine, an atypical neuroleptic with very weak affinity for dopamine D2 receptors, for which there is anecdotal evidence of efficacy for psychosis in dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). However, the use of clozapine requires cumbersome monitoring of hematological parameters and carries a risk of other adverse effects. Rivastigmine [51] and other cholinesterase inhibitors [52] have modest efficacy in improving both cognition and behavior (apathy, anxiety, delusions, and hallucinations on the NPI) in both dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease (PD) dementia [53] without the risk of extrapyramidal effects though increased tremor is sometimes limiting [52]. Considering its low D2 receptor affinity and evidence of modest efficacy for agitation in AD, quetiapine is a consideration for agitation in DLB and PDD. Anecdotal reports suggest a benefit at low doses (50–75 mg/day) in persons with DLB [54] though a small controlled, randomized, blinded clinical trial in persons with dementia and Parkinsonism did not show efficacy [55]. Though somnolence can be dose-limiting, worsened Parkinsonism is not commonly an issue. More recently, the atypical antipsychotic, pimavanserin, an antagonist or inverse agonist of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor, demonstrated efficacy for hallucinations and delusions associated with Parkinson’s disease [56]. Though agitation per se was not a target symptom in this PD population, additional studies in AD and DLB have been or are being performed (see above). In conclusion, in demented patients with agitation who have clinical features of DLB, treatment with a cholinesterase inhibitor should be initiated and, if not effective, further non-neuroleptic pharmacotherapy should be attempted.

Other potential interventions

Trazodone

Though systematic prospective controlled studies of trazodone for agitation in AD are lacking [57], its sedative effect can be utilized to treat sundowning and insomnia, particularly in light of its favorable side effect profile relative to benzodiazepines and other medications used for this indication. It may therefore secondarily help with daytime agitation, and its use as on a prn basis for acute agitation has also been advocated [58].

Prazosin

The noradrenergic system has also been implicated in the pathophysiology of agitation in AD. A small placebo-controlled trial (n = 22) in which prazosin or placebo was given to agitated AD patients showed greater improvements on the NPI and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale for those subjects on prazosin (mean dose 5.7 mg/day) without significant adverse effects [59].

Additional potential interventions

Other potential interventions which lack evidence of consistent beneficial effect but are nonetheless commonly used include anti-epileptic medications (e.g., divalproex and valproic acid, carbamazepine, gabapentin). Due to a lack of evidence of consistent efficacy and the concern for adverse effects in the elderly, we do not recommend their use in this context. Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) has been studied in a small controlled trial for neuropsychiatric symptoms, including agitation, in AD and, though well-tolerated, was not found to be effective [60]. Medications recently approved for related indications (e.g., a fixed combination of dextromethorphan and quinidine used for pseudobulbar affect [61] and pimavanserin used for psychosis in dementia due to Parkinson’s disease [45]) are also being studied for agitation in AD, but efficacy and safety in this context are yet to be demonstrated. There are several additional novel pharmacological interventions for agitation in AD also under study.

Discontinuing pharmacotherapy

Though neuropsychiatric symptoms, including agitation, tend to increase in frequency over the course of Alzheimer’s disease [62], unlike progressive cognitive deterioration, such symptoms can be transient. Therefore, it should not be assumed that a patient requiring medication for agitation will require such treatment indefinitely. Consideration should always be given to decreasing or discontinuing such medications in persons in whom agitation is no longer problematic. This is particularly true for persons whose baseline agitation was mild [63] and for medications with potential long-term side effects such as antipsychotics [64•].

Discontinuation of SSRIs deserves special consideration. First, a substantial proportion of people with dementia—about 35% in clinical trials and 25% in a large VA cohort [65]—receive SSRIs, often for long periods, sometimes for obscure reasons. Second, long-term users of SSRIs overall do not show depression but continue to show mild to moderate agitation. In patients with moderate to severe dementia being treated with SSRIs for neuropsychiatric symptoms who showed mild to moderate agitation and did not have depression, a randomized, 1-week tapering and discontinuation of the medication resulted in no significant differences between discontinuers and continuers in affective symptoms, agitation, psychosis, or apathy over 25 weeks [65]. There was a slight increase in depression scores in the discontinuer group but well below a threshold for a depression syndrome [66]. Agitation as a reason for dropping out of the trial was over three times more frequent in the discontinuers and most likely reflected withdrawal symptoms. As withdrawal symptoms are frequent with SSRIs and include, particularly in patients with dementia, worsening agitation, very slow tapers over months to include periods on subtherapeutic doses should be implemented when possible [67].

Summary and a suggested algorithm

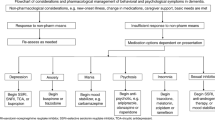

Agitation in dementia and Alzheimer’s disease is common and frequently precipitates institutionalization. There are currently no curative of consistently effective pharmacological treatments. Nonetheless, several interventions can be implemented while minimizing the potential for adverse effects. One approach to agitation in dementia was offered recently by the Lancet Commission on dementia prevention, intervention, and care (Fig. 1) [68••].

Approaches to the management of agitation in dementia (reprinted from The Lancet, volume 390, Livingston G, et.al., Dementia prevention, intervention, and care, pages 2673–2734, (2017), with permission from Elsevier) [68].

Non-pharmacological interventions

First and foremost, precipitating medical or environmental factors should be sought and addressed. The greatest degree of person-centered interaction that is feasible (e.g., distraction with music and other forms of entertainment) should be implemented.

With respect to medications:

-

1)

If sundowning or insomnia is present, the institution of treatment with gradually increasing doses of trazodone may be beneficial.

-

2)

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Citalopram can be tolerated and can yield benefits for mild to moderate agitation in more mildly cognitively impaired patients.

-

3)

Antipsychotics. Effective in individual patients, the black box warnings associated with these medications highlights the care with which their usage needs to be implemented.

-

4)

Other interventions. Additional pharmacological interventions should be considered only in the context of severe agitation when the interventions above have not been adequately beneficial.

When instituting these interventions, careful attention must be paid to the individual’s health status and concurrent medications, initiating treatments one at a time, and judiciously increasing doses. Considering the heterogeneity of patients and their underlying neuropathology and comorbidities as well as the specific nature of their “agitation”, there is no “one-size fits all” approach to agitation in AD. However, many options exist that can be prudently pursued for this common problem in this delicate population.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

•• Cummings J, Mintzer J, Brodaty H, Sano M, Banerjee S, Devanand DP, et al. Agitation in cognitive disorders: International Psychogeriatric Association provisional consensus clinical and research definition. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(1):7–17 In this review article, the expert panel of authors attempts to standardize the definition of agitation in dementia and its implementation in clinical studies.

Cohen-Mansfield J. Agitated behaviors in the elderly. II. Preliminary results in the cognitively deteriorated. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34(10):722–7.

Reisberg B, Monteiro I, Torossian C, Auer S, Shulman MB, Ghimire S, et al. The BEHAVE-AD assessment system: a perspective, a commentary on new findings, and a historical review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2014;38(1–2):89–146.

Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308–14.

Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, Smith V, MacMillan A, Shelley T, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatr Clin Neurosci. 2000;12(2):233–9.

Wood S, Cummings JL, Hsu MA, Barclay T, Wheatley MV, Yarema KT, et al. The use of the neuropsychiatric inventory in nursing home residents. Characterization and measurement. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;8(1):75–83.

Yesavage JA, Taylor JL, Friedman L, Rosenberg PB, Lazzeroni LC, Leoutsakos JS, et al. Principal components analysis of agitation outcomes in Alzheimer’s disease. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;79:4–7.

• Salzman C, Jeste DV, Meyer RE, Cohen-Mansfield J, Cummings J, Grossberg GT, et al. Elderly patients with dementia-related symptoms of severe agitation and aggression: consensus statement on treatment options, clinical trials methodology, and policy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(6):889–98 In this review article, the authors addressed potential underlying causes of the lack of consistent benefits for agitation in clinical trials, the adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics and the care with which they must be used in this context, and the need for safer and more effective treatments for agitation in dementia.

Halpern R, Seare J, Tong J, Hartry A, Olaoye A, Aigbogun MS. Using electronic health records to estimate the prevalence of agitation in Alzheimer’s disease/dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(3):420–31.

Chui HC, Zarow C, Mack WJ, Ellis WG, Zheng L, Jagust WJ, et al. Cognitive impact of subcortical vascular and Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Ann Neurol. 2006;60(6):677–87.

Wolf D, Rhein C, Geschke K, Fellgiebel A. Preventable hospitalizations among older patients with cognitive impairments and dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018:1–9.

Ihara ES, Tompkins CJ, Inoue M, Sonneman S. Results from a person-centered music intervention for individuals living with dementia. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018.

Pedersen SKA, Andersen PN, Lugo RG, Andreassen M, Sutterlin S. Effects of Music on Agitation in Dementia: A Meta-Analysis. Front Psychol. 2017;8:742.

van der Steen JT, Smaling HJ, van der Wouden JC, Bruinsma MS, Scholten RJ, Vink AC. Music-based therapeutic interventions for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;7:CD003477.

Romeo R, Zala D, Knapp M, Orrell M, Fossey J, Ballard C. Improving the quality of life of care home residents with dementia: cost-effectiveness of an optimized intervention for residents with clinically significant agitation in dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2018.

Livingston G, Kelly L, Lewis-Holmes E, Baio G, Morris S, Patel N, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for agitation in dementia: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(6):436–42.

Leng M, Liu P, Zhang P, Hu M, Zhou H, Li G, et al. Pet robot intervention for people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychiatry Res. 2018;271:516–25.

Dimitriou TD, Verykouki E, Papatriantafyllou J, Konsta A, Kazis D, Tsolaki M. Non-pharmacological interventions for agitation/aggressive behaviour in patients with dementia: a randomized controlled crossover trial. Funct Neurol. 2018;33(3):143–7.

Canevelli M, Valletta M, Trebbastoni A, Sarli G, D’Antonio F, Tariciotti L, et al. Sundowning in dementia: clinical relevance, pathophysiological determinants, and therapeutic approaches. Front Med (Lausanne). 2016;3:73.

Howard RJ, Juszczak E, Ballard CG, Bentham P, Brown RG, Bullock R, et al. Donepezil for the treatment of agitation in Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(14):1382–92.

Cummings JL, Koumaras B, Chen M, Mirski D, Rivastigmine Nursing Home Study T. Effects of rivastigmine treatment on the neuropsychiatric and behavioral disturbances of nursing home residents with moderate to severe probable Alzheimer’s disease: a 26-week, multicenter, open-label study. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2005;3(3):137–48.

Mahlberg R, Walther S, Eichmann U, Tracik F, Kunz D. Effects of rivastigmine on actigraphically monitored motor activity in severe agitation related to Alzheimer’s disease: a placebo-controlled pilot study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2007;45(1):19–26.

Herrmann N, Rabheru K, Wang J, Binder C. Galantamine treatment of problematic behavior in Alzheimer disease: post-hoc analysis of pooled data from three large trials. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(6):527–34.

Gauthier S, Feldman H, Hecker J, Vellas B, Ames D, Subbiah P, et al. Efficacy of donepezil on behavioral symptoms in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002;14(4):389–404.

Mega MS, Masterman DM, O’Connor SM, Barclay TR, Cummings JL. The spectrum of behavioral responses to cholinesterase inhibitor therapy in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56(11):1388–93.

Fox C, Crugel M, Maidment I, Auestad BH, Coulton S, Treloar A, et al. Efficacy of memantine for agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia: a randomized double-blind placebo controlled trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e35185.

Herrmann N, Gauthier S, Boneva N, Lemming OM. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of memantine in a behaviorally enriched sample of patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25(6):919–27.

Vermeiren Y, Van Dam D, Aerts T, Engelborghs S, De Deyn PP. Brain region-specific monoaminergic correlates of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41(3):819–33.

Seitz DP, Adunuri N, Gill SS, Gruneir A, Herrmann N, Rochon P. Antidepressants for agitation and psychosis in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2:CD008191.

Olin JT, Katz IR, Meyers BS, Schneider LS, Lebowitz BD. Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression of Alzheimer disease: rationale and background. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10(2):129–41.

Orgeta V, Tabet N, Nilforooshan R, Howard R. Efficacy of antidepressants for depression in Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;58(3):725–33.

Rosenberg PB, Drye LT, Martin BK, Frangakis C, Mintzer JE, Weintraub D, et al. Sertraline for the treatment of depression in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(2):136–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181c796eb.

Finkel SI, Mintzer JE, Dysken M, Krishnan KR, Burt T, McRae T. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of sertraline in the treatment of the behavioral manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease in outpatients treated with donepezil. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(1):9–18.

• Porsteinsson AP, Drye LT, Pollock BG, Devanand DP, Frangakis C, Ismail Z, et al. Effect of citalopram on agitation in Alzheimer disease: the CitAD randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2014;311(7):682–91 In this large controlled trial, a benefit of citalopram for agitation in AD was demonstrated, albeit with a risk of cardiotoxicity.

Schneider LS, Frangakis C, Drye LT, Devanand DP, Marano CM, Mintzer J, et al. Heterogeneity of treatment response to citalopram for patients With Alzheimer’s disease with aggression or agitation: the CitAD randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatr. 2016;173(5):465–72.

Schneider LS, Pollock VE, Lyness SA. A meta-analysis of controlled trials of neuroleptic treatment in dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38(5):553–63.

De Deyn PP, Rabheru K, Rasmussen A, Bocksberger JP, Dautzenberg PL, Eriksson S, et al. A randomized trial of risperidone, placebo, and haloperidol for behavioral symptoms of dementia. Neurology. 1999;53(5):946–55.

Schneider LS, Dagerman K, Insel PS. Efficacy and adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(3):191–210.

•• Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, Davis SM, Hsiao JK, Ismail MS, et al. Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1525–38. This large randomized and controlled study was designed to mimic real-world prescribing practices and therefore the results are more easily generalizable.

Sultzer DL, Davis SM, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, Lebowitz BD, Lyketsos CG, et al. Clinical symptom responses to atypical antipsychotic medications in Alzheimer’s disease: phase 1 outcomes from the CATIE-AD effectiveness trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(7):844–54.

Rosenheck RA, Leslie DL, Sindelar JL, Miller EA, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, et al. Cost-benefit analysis of second-generation antipsychotics and placebo in a randomized trial of the treatment of psychosis and aggression in Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(11):1259–68.

Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials.[see comment]. JAMA. 2005;294(15):1934–43.

Streim JE, Porsteinsson AP, Breder CD, Swanink R, Marcus R, McQuade R, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of aripiprazole for the treatment of psychosis in nursing home patients with Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(7):537–50.

Mintzer JE, Tune LE, Breder CD, Swanink R, Marcus RN, McQuade RD, et al. Aripiprazole for the treatment of psychoses in institutionalized patients with Alzheimer dementia: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled assessment of three fixed doses. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(11):918–31.

Ballard C, Banister C, Khan Z, Cummings J, Demos G, Coate B, et al. Evaluation of the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of pimavanserin versus placebo in patients with Alzheimer’s disease psychosis: a phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(3):213–22.

Rabinovici GD, Carrillo MC, Forman M, DeSanti S, Miller DS, Kozauer N, et al. Multiple comorbid neuropathologies in the setting of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology and implications for drug development. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2017;3(1):83–91.

Irwin DJ, Grossman M, Weintraub D, Hurtig HI, Duda JE, Xie SX, et al. Neuropathological and genetic correlates of survival and dementia onset in synucleinopathies: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(1):55–65.

Aarsland D, Perry R, Larsen JP, McKeith IG, O’Brien JT, Perry EK, et al. Neuroleptic sensitivity in Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonian dementias. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(5):633–7.

Shea YF, Chu LW. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome Caused by Quetiapine in an Elderly Man with Lewy Body Dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(9):e55–6.

Teng PR, Yeh CH, Lin CY, Lai TJ. Olanzapine-induced neuroleptic malignant syndrome in a patient with probable dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neuropsychiatr Clin Neurosci. 2012;24(4):E1–2.

McKeith I, Del Ser T, Spano P, Emre M, Wesnes K, Anand R, et al. Efficacy of rivastigmine in dementia with Lewy bodies: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled international study. Lancet. 2000;356(9247):2031–6.

Matsunaga S, Kishi T, Yasue I, Iwata N. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Lewy body disorders: a meta-analysis. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;19(2).

Emre M, Aarsland D, Albanese A, Byrne EJ, Deuschl G, De Deyn PP, et al. Rivastigmine for dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(24):2509–18.

Takahashi H, Yoshida K, Sugita T, Higuchi H, Shimizu T. Quetiapine treatment of psychotic symptoms and aggressive behavior in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies: a case series. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27(3):549–53.

Kurlan R, Cummings J, Raman R, Thal L, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study G. Quetiapine for agitation or psychosis in patients with dementia and parkinsonism. Neurology. 2007;68(17):1356–63.

Cummings J, Isaacson S, Mills R, Williams H, Chi-Burris K, Corbett A, et al. Pimavanserin for patients with Parkinson’s disease psychosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;383(9916):533–40.

Lopez-Pousa S, Garre-Olmo J, Vilalta-Franch J, Turon-Estrada A, Pericot-Nierga I. Trazodone for Alzheimer’s disease: a naturalistic follow-up study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2008;47(2):207–15.

Davies SJ, Burhan AM, Kim D, Gerretsen P, Graff-Guerrero A, Woo VL, et al. Sequential drug treatment algorithm for agitation and aggression in Alzheimer’s and mixed dementia. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(5):509–23.

Wang LY, Shofer JB, Rohde K, Hart KL, Hoff DJ, McFall YH, et al. Prazosin for the treatment of behavioral symptoms in patients with Alzheimer disease with agitation and aggression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(9):744–51.

van den Elsen GA, Ahmed AI, Verkes RJ, Kramers C, Feuth T, Rosenberg PB, et al. Tetrahydrocannabinol for neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2015;84(23):2338–46.

Cummings JL, Lyketsos CG, Peskind ER, Porsteinsson AP, Mintzer JE, Scharre DW, et al. Effect of dextromethorphan-quinidine on agitation in patients with Alzheimer disease dementia: a randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2015;314(12):1242–54.

Borsje P, Wetzels RB, Lucassen PL, Pot AM, Koopmans RT. The course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in community-dwelling patients with dementia: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(3):385–405.

Van Leeuwen E, Petrovic M, van Driel ML, De Sutter AI, Vander Stichele R, Declercq T, et al. Withdrawal versus continuation of long-term antipsychotic drug use for behavioral and psychological symptoms in older people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;3:CD007726.

• Brodaty H, Aerts L, Harrison F, Jessop T, Cations M, Chenoweth L, et al. Antipsychotic deprescription for older adults in long-term care: the HALT study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(7):592–600 e7. In this study, the authors demonstrated that it is frequently possible to discontinue atypical antipsychotics in agitated persons with dementia without relapse of symptoms.

Kales HC, Zivin K, Kim HM, Valenstein M, Chiang C, Ignacio RV, et al. Trends in antipsychotic use in dementia 1999–2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(2):190–7.

Bergh S, Selbaek G, Engedal K. Discontinuation of antidepressants in people with dementia and neuropsychiatric symptoms (DESEP study): double-blind, randomized, parallel group, placebo-controlled trial. BMJ. 2012;344:e1566.

Horowitz MA, Taylor D. Tapering of SSRI treatment to mitigate withdrawal symptoms. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019.

•• Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673–734 In this comprehensive article, the authors review many practical dimensions of care of patients with AD, including management of agitation.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by NIH P50 AG-005142.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

John M. Ringman declares no potential conflict of interest. Lon Schneider reports grants from NIH and grants from the State of California, during the conduct of the study, and grants from NIH, grants and personal fees from Eli Lilly, grants and other from Lundbeck, grants and personal fees from Roche/Genentech, personal fees from Merck, personal fees from AC Immune, personal fees from Avraham, personal fees from Takeda, personal fees from Cognition, grants from Novartis, grants from Biogen, personal fees and other from vTv, personal fees and other from Allergan, personal fees from Neurim, personal fees from Axovant, personal fees from Neuronix, personal fees from Eisai, and personal fees from Toyama, outside the submitted work.

Human and animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Dementia

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ringman, J.M., Schneider, L. Treatment Options for Agitation in Dementia. Curr Treat Options Neurol 21, 30 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11940-019-0572-3

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11940-019-0572-3