Abstract

This review proposes a critical discussion of the recent studies investigating the presence of alexithymia in patients suffering from different chronic pain (CP) conditions. The term CP refers to pain that persists or progresses over time, while alexithymia is an affective dysregulation, largely observed in psychosomatic diseases. Overall, the examined studies showed a high prevalence of alexithymia, especially difficulties in identifying feelings, in all the different CP conditions considered. However, the association between alexithymia and pain intensity was not always clear and in some studies this relationship appeared to be mediated by negative effect, especially depression. The role of alexithymia in CP should be clarified by future studies, paying particular attention to two aspects: the use of additional measures, in addition to the Toronto Alexithymia Scale, to assess alexithymia, and the analysis of the potential differences in the evolution of different CP conditions with reference to the presence or absence of alexithymia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The term chronic pain (CP) refers to pain that persists or progresses over time. In contrast to acute pain, which arises suddenly in response to a specific injury and is usually treatable, CP persists over time and is often resistant to medical treatments. As far as the psychological features of patients with CP conditions are concerned, alexithymia seems to play a key role [1–3]. Alexithymia is an emotional dysregulation, characterized by difficulties in identifying and describing subjective feelings, and by externally oriented thinking [4].

The present paper aims to provide a critical discussion of the recent evidence on alexithymia in patients with different CP conditions. The studies included were identified through searches in the PubMed and Ovid electronic databases; only studies in the English language were considered. Works published from November 2012 to September 2015 were analyzed. The keywords “Chronic Pain” AND “Alexithymia”, and “Chronic Pain” AND “Emotional processing” were used. The search was then extended, selecting specific CP syndromes in which alexithymia was mainly investigated.

Chronic Pain Disorders

CP is a widespread problem, with prevalence estimates at approximately 40% of the general population [5] and an enormous impact on economies.

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines CP as pain which has persisted beyond normal tissue healing time (usually 3 months) following an injury [6•]. This definition has been widely used in research and clinical practice, but has also been considered too narrow, as it does not include functional and psychobiological factors, indispensable for an accurate assessment [7, 8]. Advanced neurobiological knowledge of the involvement of the central nervous system in CP has changed the focus from the painful body region to the brain. Research has shown that lifetime pain exposures, stress responses, cognitions, and emotions can modify the individual experience of perceived pain [9–11]. Based on current knowledge, the biopsychosocial model seems to be the best approach to the study and comprehension of CP [12].

The classification of CP is complex and still controversial. Chronic clinical pain conditions are generally labeled by: (1) the site of injury (e.g., back, head, viscera); and (2) type of injury (e.g., neuropathic, arthritic, cancer, myofascial, diabetic). Clinical manifestations are often a combination of several pain conditions; even in a specific condition, many different tissue types can be involved [9].

Ultimately, it can be reasonably stated that CP disorders include a heterogeneous series of conditions. These comprise: temporomandibular disorders (TMDs): include a varied group of disorders associated with dysfunctions of the muscles of mastication, temporomandibular joints and related structures; myofascial pain syndrome: one of the commonest type of TMD, characterized by discomfort or pain in the muscles that control jaw; complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS): comprises disorders characterized by pain, usually affecting an arm or a leg, which is disproportionate to the inciting noxious event; low back pain (LBP): the most prevalent of all CP conditions, may originate from injury, disease or stresses on different structures of the body; fibromyalgia (FM): a syndrome characterized by chronic, widespread musculoskeletal pain, observed predominantly in women; migraine: a type of primary headache characterized by repetitive, unilateral, and occasionally bilateral throbbing headache attacks; and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): a functional disorder in which abdominal pain is caused by chronic alteration in bowel habit resulting in fewer bowel movements and diminished mean daily fecal output.

Alexithymia

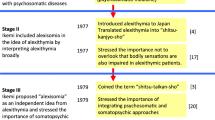

Alexithymia is a multidimensional construct, observed in several clinical conditions, particularly in “psychosomatic disorders” [13].

The term alexithymia (literally, “no words for feelings”) was first coined by Sifneos in 1973 to describe individuals who lack the ability to communicate their feelings or have limited imagination [14, 15]. Alexithymia can be considered a deficit in cognitive processing and emotional regulation [16], mainly characterized by difficulty in identifying feelings and in distinguishing between feelings and the bodily sensations of emotional arousal, by difficulty describing subjective feelings, restricted imaginative processes, as evidenced by a lack of imagination, and a stimulus-bound, externally orientated cognitive style [17]. In particular, the inability to adequately identify physical sensations as the somatic manifestations of emotions can make alexithymic individuals susceptible to incorrectly interpreting their emotional arousal as signs of disease, leading them to seek medical care for symptoms for which no clear medical explanations can be found [18, 19].

The presence of alexithymic traits can be assessed with different instruments such as observer-rated measures, including the Observer Alexithymia Scale [20] and the Toronto Structured interview for Alexithymia [21], performance-based instruments, including the Levels of Emotional Awareness Scale (LEAS) [22], and self-report measures, such as the 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20) [23, 24].

Of these different instruments, the TAS-20 is one of the most commonly employed to assess alexithymia in both research and clinical practice. Providing investigators with a reliable, validated, and common metric for measuring the construct [25, 26], the TAS-20 consists of three subscales: difficulty identifying feelings (DIF-F1), which measures the inability to distinguish between different emotions, or between feelings and the bodily sensations of emotional arousal; difficulty describing feelings (DDF-F2), which assesses the inability to verbalize subjective emotions to others; and externally-oriented thinking (EOT-F3), which evaluates the tendency of individuals to focus their attention externally and not on the inner emotional experience [25, 26].

Chronic Pain Disorders and Alexithymia

CP is recognized as a multidimensional experience with sensory, affective and cognitive components, and is viewed as a biopsychosocial phenomenon in which biological, psychological and social factors dynamically interact with each other in determining the clinical expression of pain [27–29]. Even though the role of psychological factors in understanding persistent disabling pain has been well recognized [27, 29, 30, 31•], the nature of these disorders, as well as the high rates of psychopathology in CP patients, is not fully understood [32].

Among psychological disorders, alexithymia is a multidimensional construct that may contribute to both the manifestation and intensification of CP symptomatology, entailing deficits in emotion-processing and emotion-regulating systems [33]. Alexithymia has been demonstrated to be associated with pain and pain-related functioning in individuals with CP [2, 3, 34, 35]. Although the results are still controversial [36, 37], when significant associations have been found, alexithymia has always been positively associated with pain intensity.

Tables 1 and 2 describe and summarize the main findings of the recent studies that investigated alexithymia in different CP conditions. In all the selected studies, TAS-20 or TAS-26 was used for the evaluation of alexithymia [38]. Even when the TAS-26 (the former version of the TAS-20) was employed, a three-factor structure of the questionnaire was considered.

Generic Chronic Pain Conditions

The search in electronic databases found four studies that assessed alexithymia in patients with generic CP conditions (Table 1). In the first study, Makino et al. [39••] found that alexithymia was moderately associated with pain interference (influence of pain on patient functioning) and catastrophizing in a Japanese sample of CP patients. However, these associations became non-significant when demographic variables and measures of negative affectivity (anxiety and depression) were controlled. Similarly, Saariaho et al. [40••] divided the CP sample into alexithymic and non-alexithymic according to TAS-20 scores, and found that the alexithymic group was more depressive and disabled than the non-alexithymic one. Once again, depression acted as a full mediator between alexithymia and pain disability. Shibata et al. [41••], examining the association between alexithymia and CP in a sample representative of the general population, also found that alexithymia was significantly associated with a higher prevalence of CP and that this association was mediated by a negative effect. Moreover, the DIF subscale of TAS-20 was more closely associated with pain than the other two TAS-20 subscales. Finally, Saariaho et al. [42••] explored the relationships between alexithymia, early maladaptive schemas (EMSs) and depression in a group of CP patients, and found that alexithymic CP patients obtained higher scores on all EMSs compared to non-alexithymic ones. Furthermore, alexithymic patients reported more pain intensity and pain disability and higher depression levels. The high positive correlations between the EMSs and alexithymia variables decreased when controlling for depression.

Overall, these studies showed that: (1) patients with generic CP conditions present a higher prevalence of alexithymia compared to the general population; (2) alexithymic CP patients show a significantly higher prevalence of pain than non-alexithymic ones; and (3) the association between alexithymia and pain is usually mediated by a negative effect.

Temporomandibular Disorders

The search in electronic databases found three studies that assessed alexithymia in TMD patients (Table 1). In the first study, Haas et al. [43••] analyzed facial emotion recognition (FER) abilities in a group of TMD patients, elucidating if and to what extent FER might be influenced by alexithymia, depression and somatization. They found that the TMD patients had lower FER abilities compared to the healthy controls (HC), especially in identifying facial emotions with sadness and fear (under-recognized), and disgust (over-recognized). Moreover, TMD patients showed higher levels of alexithymia on TAS-26, in particular on the DIF factor, compared to the HC. Both alexithymia and somatization were able to explain a great part of the variance of the FER measurement. Castelli et al. [44•] instead investigated the presence of alexithymia, anger, and psychological distress in a sample of myofascial TMD patients. They found a higher prevalence of pain, depression, anxiety and emotional distress in myofascial TMD patients compared to the HC. Similarly, myofascial TMD patients presented significantly higher alexithymic scores, in particular on the DIF subscale of TAS-20. With regard to anger, a significant difference between the two samples emerged only on the Anger Expression-In scale, indicating that myofascial TMD patients cope with emotions and physical or psychological distress by holding in or suppressing angry feelings. No significant correlation was found between pain intensity and alexithymia or other psychological measures. Finally, Mingarelli et al. [45••] analyzed the relationship between alexithymia and pain, poor health, and social difficulties in a group of TMD patients. Performing multiple stepwise regressions, they found that alexithymia partially explained pain (10%), poor health (31%), and social difficulties (7%) in TMD patients. Moreover, a direct comparison of TMD patients based on alexithymia scores,showed a higher prevalence of pain in alexithymic patients compared to non-alexithymic ones.

Overall, these studies showed that (1) TMD patients display a higher prevalence of alexithymic features compared to the HC, and (2) alexithymia is positively correlated with difficulties in social cognition skills (in particular, FER abilities), psychological distress and, almost always, pain.

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome and Low Back Pain

In the only recent study investigating alexithymic features in CRPS patients (Table 1), Margalit et al. [46••] examined the relationships between alexithymia, psychological distress and pain in a sample of CRPS patients compared to a group of chronic LBP patients of the same gender and age. They found that CRPS patients showed higher levels of alexithymia on all three factors of TAS-20, and psychological distress (anxiety and depression) when compared to the LBP group. In addition, pain was significantly associated with alexithymia and the DIF factor only in the CRPS group, independently of psychological distress.

Fibromyalgia

The search in electronic databases found four studies that assessed alexithymia in FM patients and one that compared FM and RA patients to the HC (Table 2).

In the first study, Castelli et al. [47••] found higher levels of alexithymia in a group of FM women (20%) with respect to the general population; in this case, the difference was due mainly to the DIF factor of the TAS-20. Moreover, studying the quality of life in FM patients, in both regression analyses performed, they found that, when competing predictors, i.e. pain intensity and psychological distress variables, were added into the model, alexithymia ceased to be significant in explaining the health-related quality of life variance.

Peñacoba-Puente et al. [48••] instead analyzed the evolution of alexithymia, anxiety, and depression associated with FM in three age groups of patients, compared to their evolution in the same age groups of the HC. They found higher levels of alexithymia, anxiety, and depression in the FM group compared to the HC. Furthermore, young FM women (<35 years) exhibited fewer alexithymia, anxiety or depression symptoms compared to older patients (≥65 years). Alexithymia also followed a similar pattern in the HC (although with significantly lower scores than in the FM group), increasing with age. On the other hand, Martinez et al. [49••] investigated the moderating role of alexithymia in the relationship between emotional distress and pain appraisal (pain catastrophizing, fear of pain, and vigilance to pain) variables in FM. They found that FM patients presented significantly more difficulties in identifying and describing feelings compared to the HC. Lastly, they found that the DIF factor moderated the relationship between anxiety and pain catastrophizing, while DDF moderated the link between anxiety and fear of pain. Di Tella et al. [50••] instead investigated, the social-cognitive profile of FM patients, analyzing affective Theory of Mind (ToM) and emotional processing abilities. They found that FM patients showed significantly higher difficulties in their own affect regulation (alexithymia) in the recognition of other’s emotions, and in representing other people’s mental states (affective ToM) compared to the HC. In particular, the FM group presented significantly higher levels of alexithymia, especially in the DIF and DDF subscales of TAS-20, and more difficulties in recognizing other’s emotions, particularly anger and disgust.

The last study selected [51••] investigated the differences between women with painful rheumatic conditions (PRC) (FM and rheumatoid arthritis patients) and the HC on alexithymia and emotional awareness measurements. They found that the total and DIF and DDF subscale scores of the TAS-20 were significantly higher among patients with PRC than among the HC. Moreover, the PRC patients had a lower ability to describe their own emotional experience, measured with the LEAS, compared to the HC. Finally, performing a logistic regression analysis, they found that the LEAS, but not the TAS-20, significantly predicted the status group after controlling for anxiety and depression.

Overall, these studies show that: (1) FM patients exhibit a higher prevalence of alexithymia, especially difficulties in identifying and describing feelings, compared to the HC; (2) alexithymic patients present higher levels of pain, compared to non-alexithymic ones, even though this association is often mediated by psychological factors (especially depression); and (3) FM patients show difficulties in some social cognition skills (affective ToM and emotional processing abilities).

Chronic Migraine

Only one study has recently investigated alexithymic features in chronic migraine (see Table 2). Vieira et al. [52••] examined the relationships between depression, anxiety, alexithymia, self-reflection, insight, and quality of life in a group of migraine suffers compared to the HC. They found that migraine patients showed higher levels of depression, anxiety and alexithymia, and lower levels of quality of life, self-reflection and insight, compared to the HC. In the migraine group, pain frequency in the previous 3 months was predicted by anxiety and one alexithymia factor (the ability to identify and describe feelings and distinguish them from bodily sensations). Moreover, a binary regression analysis between the two groups revealed that migraine might characterize individuals with high anxiety, a low quality of life, and the presence of a concrete thinking style.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

The search in electronic databases found two group studies that assessed alexithymia in IBS patients (Table 2). Phillips et al. [53••] examined the role of psychosocial factors in predicting both belonging either to the IBS or to the control group, and the severity of IBS symptoms. They found the most relevant group differences on the psychological distress measurements, total and EOT and DIF subscales scores of TAS-20, and the emotional inhibition schema of The Young Schema Questionnaire Short Form. They also found that the best predictors of IBS were alexithymia, the defectiveness/shame schema, and four coping dimensions (active coping, instrumental support, self-blame, and positive reframing), while predictors of IBS symptom severity were DIF and DDF factors, gender, the schemas of defectiveness/shame and entitlement, and global psychological distress. Porcelli et al. [54••] instead explored the independent contribution of alexithymia and gastrointestinal-specific anxiety (GSA) in predicting the severity of IBS symptoms. They found a high prevalence of alexithymia in IBS patients (54.2%), especially in those in the high severity IBS range, regardless of IBS types. Alexithymia and GSA were associated with IBS severity to a similar degree, but alexithymia explained much more unique variance in IBS severity as compared with GSA.

Overall, these studies showed that (1) IBS patients display higher levels of alexithymia compared to the general population, and (2) alexithymia (especially the DIF and DDF facets) turns out to be a strong predictor of IBS severity.

Conclusions

Chronic pain disorders include a heterogeneous series of syndromes in which several aspects are implicated in the onset and evolution of the different conditions. Among the different causes, psychological factors, in particular alexithymia, may contribute to enhance the disability generated by these pathologies. Alexithymia is, in fact, an affective dysregulation that makes individuals incapable of adequately regulating and processing their own emotions. This could lead CP patients to wrongly interpret their emotional arousal as signs of disease and to seek medical care for symptoms for which there are no medical explanation [18].

The present review illustrated and discussed the current studies that have investigated the presence of alexithymia in various CP disorders. The available studies show a high prevalence of alexithymic features, especially difficulties in identifying feelings, in all the different CP conditions considered. However, the association between alexithymia and pain intensity is not always clear, and in some of the selected studies this relationship was not found [44•] or appears to be mediated by negative effects, particularly depression [39••, 40••, 41••, 42••]. Previous studies have also confirmed this pattern of results, with no correlation [37, 55], positive correlation [2, 56], or mixed results [57] found.

One possible explanation can be related to the multidimensional nature of pain, which it has been suggested includes at least two dimensions, one affective and the other sensory [58]. The sensory component refers to the intensity of pain, while the affective one is linked to the unpleasant experiences of pain. The studies that have taken into account this distinction have found a specific association only between alexithymia and the affective dimension of pain in CP patients [34, 35]. The affective dimension of pain relies, in fact, on a specific brain structure, i.e. the limbic system, which is also essential in regulating and processing emotions. For this reason, it is possible that studies which used a one-dimensional measurement to assess pain in CP patients failed to find a relationship with alexithymia.

Another possible explanation, in particular for the mediation role of psychological distress, could be that individuals with a high degree of alexithymia have not only a limited ability to process emotions but also great difficulty in verbal communication of psychological distress, and fail to enlist the aid or comfort of other people [17]. This could lead to increased emotional distress and ultimately have a negative effect on depression and anxiety levels. This unclear evidence indicates the need to throw light on the nature of this association. We hypothesized two possible strategies to reach this object. The first could be the use of more accurate measurements for the assessment of both pain and alexithymia. In particular, it could be useful to employ a multidimensional pain measure for differentiating the two components of pain, and a performance-based instrument or a structured interview, in addition to the usually used self-report measures (such as the TAS-20), for the assessment of alexithymia. Explicit self-report measures require, paradoxically, the respondents to be aware of their reduced ability to identify and describe feelings [59]. In line with this assumption, Baeza-Velasco et al. [51••], the only ones who also used a performance-based instrument, showed that the LEAS, but not the TAS-20, significantly predicted group status after controlling for anxiety and depression.

The second strategy could be to investigate the potential differences in the progress of the different CP conditions with reference to the presence or absence of alexithymia. In addition, the cross-sectional design used by most of the studies analyzed does not permit inferring whether alexithymia can be considered as an outcome or a determinant of CP. The idea of a double characterization of alexithymia, which has been recognized as a primary or a secondary emotional dysregulation, is now accepted. Primary alexithymia is currently viewed as a more or less stable personality trait that is molded during childhood and early adult years, while secondary alexithymia is considered a condition occurring later in life either due to psychological trauma or as a direct insult to brain regions supporting emotion-processing abilities and awareness [60].

Prospective longitudinal studies are, therefore, necessary to clarify the direction of the relationship between alexithymia and CP, the role of alexithymia in the development and evolution of pain, and the influence of alexithymia on psychopathological symptoms in CP patients.

A further approach for future studies would be the additional use of neuroimaging techniques in order to examine the possible structural and functional alterations in emotion-related brain areas among persons with CP and alexithymia. Neuroimaging data could, in fact, complete and corroborate the profile resulting from clinical and psychological assessment.

Clarifying to what extent alexithymia contributes or does not to chronic pain would allow a better understanding of pain etiology and the improvement of more targeted treatments, based on the patient’s needs, in which both physical and psychological dimensions would have to be considered.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Di Tella M, Castelli L. Alexithymia e Fibromyalgia: clinical evidence. Front Psychol. 2013;4:909.

Glaros AG, Lumley MA. Alexithymia and pain in temporomandibular disorder. J Psychosom Res. 2005;59:85–8.

Lumley MA, Radcliffe AM, Macklem DJ, et al. Alexithymia and pain in three chronic pain samples: comparing Caucasians and African Americans. Pain Med. 2005;6:251–61.

Taylor GJ. Alexithymia: Concept, measurement, and implications for treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:725–32.

Tsang A, Von Korff M, Lee S, et al. Common chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries: gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disorders. J Pain. 2008;9:883–91.

Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain: descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. 2nd ed. Seattle: IASP Press; 1994. Outside the review period, but given its importance in the description and classification of chromic pain syndromes, its inclusion is warranted.

Flor H, Turk D. Basic concepts of pain. Chronic pain: an integrated biobehavioral approach. Seattle: IASP Press; 2011. p. 13–6.

Loeser J, Melzack R. Pain: an overview. Lancet. 1999;353:1607–9.

Apkarian V, Baliki M, Geha P. Towards theory of chronic pain. Prog Neurobiol. 2009;87:81–97.

Apkarian V, Hashmi J, Baliki M. Pain and the brain: specificity and plasticity of the brain in clinical chronic pain. Pain. 2011;152:49–64.

Lumley MA, Cohen J, Borszcz G, et al. Pain and emotion: A biopsychosocial review of recent research. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67:942–68.

Gatchel RJ, Peng YB, Peters ML, et al. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: Scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:581–624.

Taylor GJ. Recent development in alexithymia theory and research. Can J Psychiatry. 2000;45:134–42.

Lesser IM. Current Concepts in Psychiatry – Alexithymia. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:690–2.

Sifneos P. The prevalence of “alexithymic” characteristics in psychosomatic patients. Psychother Psychosom. 1973;22:225–62.

Kooiman CG, Bolk JH, Rooijmans HG, et al. Alexithymia does not predict the persistence of medically unexplained physical symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:224–32.

Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JDA. Disorders in affect regulation: alexithymia in medical and psychiatric illness. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press; 1997.

Lumley MA, Stettner L, Wehmer F. How are alexithymia and physical illness linked? A review and critique of pathways. J Psychosom Res. 1996;41:505–18.

Tuzer V, Bulut SD, Bastug B, et al. Causal attributions and alexithymia in female patients with fibromyalgia or chronic low back pain. Nord J Psychiatry. 2011;65:138–44.

Haviland MG, Warren WL, Riggs ML. An observer scale to measure alexithymia. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:385–92.

Bagby RM, Taylor GJ, Parker JD, et al. The development of the toronto structured interview for alexithymia: item selection, factor structure, reliability and concurrent validity. Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75:25–39.

Lane RD, Schwartz GE. Levels of emotional awareness – a cognitive developmental theory and its application to psychopathology. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:133–43.

Bagby RM, Parker JDA, Taylor GJ. The twenty-item Toronto alexithymia scale I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38:33–40.

Bagby RM, Taylor GJ, Parker JDA. The twenty-item toronto alexithymia Scale II. Convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38:23–32.

Lumley MA, Neely LC, Burger AJ. The assessment of alexithymia in medical settings: implications for understanding and treating health problems. J Pers Assess. 2007;89:230–46.

Taylor GJ, Bagby RM. New trends in alexithymia research. Psychother Psychosom. 2004;73:68–77.

Dersh J, Gatchel RJ, Polatin P. Chronic spinal disorders and psychopathology: Research findings and theoretical considerations. Spine. 2001;1:88–94.

Magid CS. Pain, suffering, and meaning. JAMA. 2000;283:111.

Sullivan MD. Finding pain between minds and bodies. Clin J Pain. 2001;17:146–56.

Gatchel RJ. Perspectives on pain: A historical review. In: Gatchel RJ, Turk DC, editors. Psychosocial Factors in Pain. New York: The Guilford Press; 1999. p. 3–17.

Manchikanti L, Fellows B, Singh V. Understanding psychological aspects of chronic pain in interventional pain management. Pain Physician. 2002;5:57–82. A review analyzing the prevalence of psychological distress in chronic pain disorders and its impact on the diagnosis and management of pain interventions. (Outside the review period, but its inclusion is warranted.).

Sharp J, Keefe B. Psychiatry in chronic pain: a review and update. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2005;7:213–9.

Bagby RM, Taylor GJ. Affect dysregulation and alexithymia. In: Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JDA, editors. Disorders of affect regulation. Alexithymia in medical and psychiatric illness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997. p. 29–32.

Huber A, Suman AL, Biasi G, et al. Alexithymia in fibromyalgia syndrome: associations with ongoing pain, experimental pain sensitivity and illness behavior. J Psychosom Res. 2009;66:425–33.

Lumley MA, Smith JA, Longo DJ. The relationship of alexithymia to pain severity and impairment among patients with chronic myofascial pain: comparisons with self-efficacy, catastrophizing, and depression. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:823–30.

Celikel FC, Saatcioglu O. Alexithymia and anxiety in female chronic pain patients. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2006;5:13.

Cox BJ, Kuch K, Parker JD, et al. Alexithymia in somatoform disorder patients with chronic pain. J Psychosom Res. 1994;38:523–7.

Taylor GJ, Ryan D, Bagby RM. Toward the development of a new self-report alexithymia scale. Psychother Psychosom. 1985;44:191–9.

Makino S, Jensen MP, Arimura T, et al. Alexithymia and chronic pain: The role of negative affectivity. Clin J Pain. 2013;29:354–61. One of the four studies investigating the relationship between alexithymia and generic chronic pain conditions. Alexithymia, in particular the DIF subscale of TAS-20, was associated with pain interference, catastrophizing, and negative affectivity. However, these associations became non-significant when measures of negative affectivity were controlled for.

Saariaho AS, Saariaho TH, Mattila AK, et al. Alexithymia and depression in a chronic pain patient sample. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35:239–45. One of the four studies investigating the relationship between alexithymia and generic chronic pain conditions. CP patients showed a high prevalence of alexithymia (19.2%). Pain variables were not associated with alexithymia when depression was controlled for.

Shibata M, Ninomiya T, Jensen MP, et al. Alexithymia is associated with greater risk of chronic pain and negative affect and with lower life satisfaction in a general population: the Hisayama Study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90984. One of the four studies investigating the relationship between alexithymia and generic chronic pain conditions. The study showed that alexithymia was significantly associated with a higher prevalence of CP and that this association was mediated by negative affect.

Saariaho AS, Saariaho TH, Mattila AK, et al. Alexithymia and Early Maladaptive Schemas in chronic pain patients. Scand J Psychol. 2015;56:428–37. One of the four studies investigating the relationship between alexithymia and generic chronic pain conditions. Alexithymic patients scored higher on EMSs and had more pain intensity, pain disability and depression than non-alexithymic ones.

Haas J, Eichhammer P, Traue HC, et al. Alexithymic and somatisation scores in patients with temporomandibular pain disorder correlate with deficits in facial emotion recognition. J Oral Rehabil. 2013;40:81–90. One of the three studies investigating the relationship between alexithymia and TMDs. TMD patients showed facial emotion recognition deficits that are partially explained by concomitant alexithymia and somatisation.

Castelli L, De Santis F, De Giorgi I, et al. Alexithymia, anger and psychological distress in patients with myofascial pain: a case-control study. Front Psychol. 2013;4:490. One of the three studies investigating the relationship between alexithymia and TMDs, in particular myofascial TMD . Patients with myofascial TMD showed significantly higher scores on alexithymia, depression, anxiety and emotional distress measures compared to the HC.

Mingarelli A, Casagrande M, Di Pirchio R, et al. Alexithymia partly predicts pain, poor health and social difficulties in patients with temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Rehabil. 2013;40:723–30. One of the three studies investigating the relationship between alexithymia and TMDs. TMD patients with higher levels of alexithymia had more pain than those with moderate or low alexithymia.

Margalit D, Ben Har L, Brill S, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome, alexithymia, and psychological distress. J Psychosom Res. 2014;77:273–7. The only recent study investigating the relationship between alexithymia and CRPS. CRPS patients showed higher levels of alexithymia compared to LBP controls. Moreover, pain severity was significantly associated with higher levels of alexithymia and psychological distress among CRPS patients, but not among the HC.

Castelli L, Tesio V, Colonna F, et al. Alexithymia and psychological distress in fibromyalgia: prevalence and relation with quality of life. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30:70–7. One of the six studies investigating the relationship between alexithymia and PRCs, in particular FM. FM patients showed high levels of alexithymia (20%), especially on the DIF subscale of TAS-20.

Peñacoba-Puente C, Velasco Furlong L, Écija Gallardo C, et al. Anxiety, depression and alexithymia in fibromyalgia: are there any differences according to age? J Women Aging. 2013;25:305–20. One of the six studies investigating the relationship between alexithymia and PRCs, in particular FM. FM patients showed higher levels of alexithymia, anxiety, and depression compared to the HC. Moreover, young women with FM (<35 years) showed lower alexithymia, anxiety, and depression levels compared to older patients (≥65 years).

Martínez MP, Sánchez AI, Miró E, et al. Relationships between physical symptoms, emotional distress, and pain appraisal in fibromyalgia: the moderator effect of alexithymia. J Psychol. 2015;149:115–40. One of the six studies investigating the relationship between alexithymia and PRCs, in particular FM. FM patients showed significantly higher levels of alexithymia compared to the HC. Moreover, the DIF factor of TAS-20 moderated the relationship between anxiety and pain catastrophizing, and the DDF moderated the relationship between anxiety and fear of pain.

Di Tella M, Castelli L, Colonna F, et al. Theory of mind and emotional functioning in fibromyalgia syndrome: an investigation of the relationship between social cognition and executive function. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116542. One of the six studies investigating the relationship between alexithymia and PRCs, in particular FM. FM patients showed impairments in both regulation of their own affect (alexithymia) and recognition of other’s emotions, as well as in representing other’s mental states.

Baeza-Velasco C, Carton S, Almohsen C, et al. Alexithymia and emotional awareness in females with Painful Rheumatic Conditions. J Psychosom Res. 2012;73:398–400. One of the six studies investigating the relationship between alexithymia and PRCs. All TAS-20 scores were significantly higher among PRC women compared to the HC. Moreover, PRC females had lower capacities to describe their own emotional experience on LEAS.

Vieira RV, Vieira DC, Gomes WB, et al. Alexithymia and its impact on quality of life in a group of Brazilian women with migraine without aura. J Headache Pain. 2013;14:18. The only recent study investigating the relationship between alexithymia and chronic migraine. Women with migraine had higher levels of depression, anxiety and alexithymia, and lower levels of quality of life, self-reflection and insight, compared to the HC.

Phillips K, Wright BJ, Kent S. Psychosocial predictors of irritable bowel syndrome diagnosis and symptom severity. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75:467–74. One of the two studies investigating the relationship between alexithymia and IBS. The IBS group showed higher levels of alexithymia (total, DIF and EOT scores) compared to the HC. In addition, the DIF and DDF scales were two of the significant predictors of IBS symptom severity.

Porcelli P, De Carne M, Leandro G. Alexithymia and gastrointestinal-specific anxiety in moderate to severe irritable bowel syndrome. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55:1647–53. One of the two studies investigating the relationship between alexithymia and IBS. IBS severity was highly associated to both alexithymia and gastrointestinal-specific anxiety, which were also associated to each other.

Friedberg F, Quick J. Alexithymia in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: association with momentary, recall, and retrospective measures of somatic complaints and emotions. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:54–60.

Sayar K, Gulec H, Topbas M. Alexithymia and anger in patients with fibromyalgia. Clin Rheumatol. 2004;23:441–8.

Celikel F, Saatcioglu O. Alexithymia and anxiety in female chronic pain patients. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2006;5:13.

Melzack R, Katz J. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: appraisal and current status. In: Turk DC, Melzack R, editors. Handbook of pain assessment. New York: Guilford Press; 1992. p. 152–68.

Parling T, Mortazavi M, Ghaderi A. Alexithymia and emotional awareness in anorexia nervosa: time for a shift in the measurement of the concept? Eat Behav. 2010;11:205–10.

Becerra R, Amos A, Jongenelis S. Organic alexithymia: a study of acquired emotional blindness. Brain Inj. 2002;16:633–45.

Acknowledgments

Lorys Castelli was supported by University of Turin grants (“Ricerca scientifica finanziata dall’Università” Linea Giovani; http://www.unito.it) and CRT Foundation project “Componenti psicologiche e psicosomatiche nella sindrome fibromialgica”. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

MDT and LC declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

With regard to the authors’ research cited in this paper, all procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. In addition, all applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Chronic Pain

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Di Tella, M., Castelli, L. Alexithymia in Chronic Pain Disorders. Curr Rheumatol Rep 18, 41 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-016-0592-x

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-016-0592-x