Abstract

Anxiety disorders are common and disabling. Cognitive behavior therapy is the treatment of choice but is often difficult to obtain. Automated, internet-delivered, cognitive behavior therapy (iCBT) courses may be an answer. There are three recent systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials that show that the benefits are substantial (d = 1.0) and similar to face to face CBT. There are two large effectiveness trials that demonstrate strong effects when iCBT is used in primary care; 60 % of patients who complete the courses no longer meet diagnostic criteria. The courses are suitable for most people with a primary anxiety disorder. Research studies usually exclude people whose anxiety is secondary to schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or substance abuse or who are actively suicidal. Little additional input from clinicians is required. Patients find the courses very convenient. Clinically, the principal advantage is the fidelity of the treatment. What you prescribe is what the patient sees.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anxiety disorders collectively are the most common type of mental disorders, affecting over one quarter of individuals during their lifetime [1]. Anxiety disorders are characterized by excessive fear and anxiety and related maladaptive behaviors such as avoidance. In the DSM-5, anxiety disorders include generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, agoraphobia, social anxiety disorder, specific phobia, and separation anxiety disorder. The anxiety disorders have high lifetime comorbidity rates (up to 75 %) [2], but are differentiated by the types of situations, objects, or stimuli that trigger the individual’s fears. They tend to have onset during childhood or adolescence, can become chronic and relapsing, and are associated with high functional impairment and reduced quality of life and increased risk of developing other psychiatric disorders, in particular depression.

Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (e.g., NICE guidelines) recommend cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) as the first-line treatment for anxiety disorders. However, antidepressant medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) remain a standard treatment for both the anxiety and depressive disorders due to their relatively low cost and availability. Prescription rates continue to rise despite growing recognition that their long-term benefits are small, and the potential for harm from side effects and withdrawal syndromes is high [3].

Provision of CBT as the “gold-standard” treatment for anxiety disorders is critical, yet face-to-face CBT is not always easy to access because of long waiting lists, the lack of skilled practitioners, high costs, and geographical barriers. In part to overcome these barriers and in part to increase the accessibility and lower the costs of CBT, internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy (iCBT) has been developed [4].

iCBT courses are essentially “CBT 101.” Although each iCBT program differs slightly in its focus, delivery style, and content, the majority of iCBT courses include psychoeducation about the target disorder and present a model for recovery that involves learning practical evidence-based techniques to reduce maladaptive thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that characterize and maintain the target disorder. Most existing courses include the core skills of CBT: self-monitoring, cognitive restructuring (“thought challenging”), and behavioral experiments to change unhelpful cognitions, graded exposure to reduce avoidance, activity scheduling to increase engagement in physical exercise, pleasurable and achievement-related activities, structured problem solving, and relapse prevention. The content of iCBT courses differ from CBT provided by clinicians engaging in tele-psychiatry; because the content is standardized and automated, there is minimal if no enquiry into a patient’s history and minimal tailoring of the content to individual patient differences. One of the strengths of iCBT courses is their high fidelity because of their consistency across patients.

Most of the courses evaluated to date require an individual to login to access a secure website. The courses are arranged in a sequence of weekly lessons or text-based “modules” that progressively build upon the previous lesson or module. Each course is to be completed within a specified timeframe, typically aligned with a traditional face-to-face CBT sequencing (e.g., 12 weeks). Practical homework exercises require the participant to practice the skills in their daily life and aim to consolidate learning. Most existing courses include routine outcome monitoring via the completion of standardized self-report questionnaires, which allow the clinician to monitor safety, outcomes, and progress. Automated alerts are sent to the patient or clinician if additional actions are required.

Efficacy: Does iCBT Work for the Anxiety Disorders?

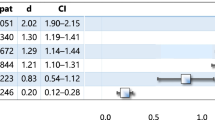

There are two recent systematic reviews which indicate that iCBT for an anxiety disorder is superior to both waiting-list control conditions and active control groups. Andrews et al. [5] identified 22 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of iCBT used in people who met the criteria for a depressive disorder, panic, social anxiety disorder, or GAD. The mean effect size demonstrating superiority over the control group was Cohen’s d = 0.9, and the benefit was evident across all four disorders. These results equate to a number needed to treat (NNT) of 2; for every two individuals who receive iCBT, one recovers. Improvement from iCBT was maintained throughout follow-up, a median of 26 weeks. Acceptability, as indicated by adherence and satisfaction, was good. The research quality of included RCTs was also good and risk of bias was low. Five studies showed that iCBT was equally beneficial as traditional face-to-face CBT. Hedman et al. [6••] more recently completed a systematic review of 103 RCTs across 25 clinical disorders. The authors concluded that, in terms of the American Psychological Association’s criteria for empirically supported treatment, iCBT had met the criteria for a well-established treatment for depression and social anxiety disorder and for panic disorder/agoraphobia, with large effect sizes across the anxiety disorders (Cohen’s d = 1.13, 95 % confidence interval (CI) = .99–1.28 for social anxiety disorder and d = 1.42, 95 % CI = .62–2.92, for panic disorder/agoraphobia).

Most recently, Mewton et al. [7••] provided a systematic review of randomized controlled trials of iCBT for anxiety disorders published before August 2013. They included 27 trials that examined the efficacy of iCBT programs compared with waiting list or active control. The review included trials of iCBT for GAD (n = 5 studies, d = 1.2), panic disorder (n = 6, d = 1.3), social anxiety disorder (n = 8, d = 0.9), transdiagnostic therapy for comorbid anxiety disorders, or comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders (n = 6, d = 0.6) as well as obsessive compulsive disorder (n = 2, d = 0.9). Between-group effect sizes were moderate to large for all disorders, and the weighted mean effect size for the 27 iCBT studies was d = 1.0, NNT = 2. The efficacy of iCBT was also found to be commensurate with face-to-face CBT (n = 5 studies, d = 0.15) whether delivered individually or in group format. iCBT is effective and has been demonstrated to be as effective as conventional CBT.

In all these studies, while the iCBT courses were tailored to the principal diagnosis, no variation occurred in terms of comorbidity. The question of how best to treat comorbidity among the anxiety disorders using iCBT is still to be determined. Nordgren et al. [8] investigated the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of iCBT that was tailored to address comorbidities and preferences of primary-care patients with a principal anxiety disorder. The results showed that such a tailored course was beneficial (d = 0.6) and cost-effective when compared with the control groups. The degree of improvement was comparable to that observed by Mewton et al. (2013) for transdiagnostic courses (see above). Comparison trials between iCBT courses that target one disorder versus transdiagnostic or tailored iCBT programs that target multiple comorbidities are needed. This is especially critical as Titov et al. [9] have showed that individuals who completed disorder-specific iCBT course for social anxiety disorder demonstrated substantial reductions in comorbid depression and GAD symptoms, reductions that paralleled the reduction in social anxiety symptoms. Berger et al. [10] compared a tailored approach to a standard iCBT approach and found both to be equally effective. Based on the intention-to-treat sample, mean between-group effect sizes versus wait-list controls were d = 0.8 for the tailored treatment and d = 0.8 for the standardized treatment. Thus, there was no advantage in terms of symptom reduction from varying the courses according to comorbidity.

Effectiveness: Does iCBT Work Outside of Tightly Controlled Clinical Trials?

iCBT has been shown to be effective for anxiety disorders and depression in RCTs. A critical question for the field is to determine whether these findings generalize to patients under the care of their primary care clinician or mental health clinician. An uncontrolled open trial was conducted by Mewton et al. [11] with 588 patients who were prescribed a six-lesson iCBT course for GAD by their primary care clinician via ThisWayUpClinic (https://thiswayup.org.au/clinic). The primary care clinician supervised their patient through the course and remained clinically responsible for their patient throughout the course. All six lessons were completed by 55 % of patients. Non-completers demonstrated statistically significant reductions in psychological distress prior to discontinuing the course. For those who completed the course, effect sizes on the primary outcome measures were large (d > 1). Over 60 % of individuals who met the criteria for moderate to severe GAD met the criteria for remission upon treatment completion. The study indicates that iCBT for GAD is effective in generating positive, clinically significant outcomes among typical patients treated under the usual conditions in primary care. In a similar study by Newby et al. [12] of 707 patients treated by their primary care clinicians with the ThisWayUpClinic transdiagnostic anxiety and depression course, effect sizes of the reductions in depression and generalized anxiety between baseline and post-treatment were large (d > 0.9) and consistent with the findings in the efficacy RCT of the depression and anxiety program [13]. Internet-delivered CBT courses for panic disorder, PTSD, and depression have also been demonstrated to remain effective, with large effect sizes (Cohen’s d 1.2–1.9) and good adherence (up to 79 %) when delivered in specialist psychiatric settings as part of routine clinical care [e.g., 14–16]. It is concluded that iCBT is effective in routine clinical practice.

Who Should We Treat Using iCBT and Who Should We Exclude?

To date, there has been little success in identifying patients who will benefit from iCBT, versus those who do not. Hedman et al. [17] found that higher ratings of treatment credibility, better adherence to treatment, and lower baseline anxiety and depression predicted better treatment outcomes 6 months following iCBT for social anxiety disorder [18]. Other studies of iCBT in routine practice and primary care have not shown patient characteristics that predict who will benefit from iCBT for GAD or comorbid anxiety disorders; neither gender nor age, nor education, nor severity, nor comorbidity are predictive of treatment benefit although the older patients are more adherent than the youngest patients [8, 19]. Patients using internet clinics are similar to those who seek treatment at face-to-face clinics [20]. Additional research specifically addressing potential moderators is needed to advance our understanding of this issue.

Contraindications for iCBT are also currently unknown. We do not recommend iCBT for people whose anxiety is secondary to schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or drug dependence and people who are dependent on benzodiazepines, as these samples have been routinely excluded in most studies. Research is needed to determine whether iCBT for anxiety disorders is beneficial for people with these comorbidities.

Existing RCTs include individuals who meet diagnosis for the target anxiety disorder based on validated telephone-administered or face-to-face diagnostic interviews, such as the MINI [21] or SCID [22]. About half the people included in the published RCTs were in current treatment and taking medication, and most studies asked participants to maintain a stable dose of medication and/or psychotherapy while participating in the clinical trial.

Suicidality is perceived as a contraindication to iCBT. Efficacy studies have commonly excluded people at high risk for suicide attempts, including those who have previously attempted suicide, those who thought about suicide more than half the time, and those who had a plan or intend to attempt suicide. There is evidence that the frequency of suicidal ideation decreases significantly in concert with depression in people undergoing iCBT for depression [23, 24] or iCBT for anxiety and depression in primary care [7••, 12, 25]. Considering the exclusions in efficacy trials, further research is still needed to evaluate the most effective methods to maximize the safety of iCBT programs for anxiety when accompanied by suicidal ideation. Further, as there is currently insufficient knowledge of negative effects associated with iCBT, reporting of clearly defined adverse events in efficacy trials should become routine [26••].

What Clinician Input Is Required?

Evidence shows that clinician guidance during iCBT contributes to better adherence and better outcomes in terms of symptom reduction for the patient [27]. Adherence is likely to be improved if the prescribing clinician explains the reason for prescribing iCBT and the likely benefits and possible side effects. The time spent guiding a patient through iCBT is a fraction of what face-to-face CBT entails: the average time spent contacting patients in our recent clinical trials was under 30 min per person per course, and some require no direct clinical contact as they choose to complete the course by themselves. At present, more research is needed to examine the impact of the type, content, and frequency of clinician contact to determine the critical aspects of clinician guidance that promote positive effects. However, the available evidence suggests that it does not appear to matter who provides the guidance: primary care clinicians achieve positive effects [12], clinical psychology trainees under the supervision of more experienced clinical psychologists achieve positive results [28], and practice managers or “technicians” do as well as more experienced clinicians [29].

Many iCBT systems send alerts to the clinician about their patient’s progress and symptom scores, which is a significant advantage of iCBT over medication. ThisWayUpClinic provides each clinician with the ability to log on and see a record of the progress of all of their patients. It only routinely sends an email when a patient has completed a lesson of the iCBT course or if the distress score at any lesson has risen significantly. The clinic manager or treating practitioner is encouraged to contact the patient if their progress is falling behind or if their distress has increased. Most patients know why their distress has increased and those who are concerned welcome the show of interest and offer of help and, interestingly, continue to manage without having to consult, secure that help is at hand if required.

What are the Advantages and Disadvantages/Harms of iCBT Courses?

There are five main advantages of iCBT:

-

1)

Efficacy: iCBT courses consistently demonstrate large, consistent, and long-term reductions in anxiety and have demonstrated comparable ES to face-to-face CBT. iCBT courses that have been developed independently produce similar benefits, and the efficacy of many iCBT courses have been replicated independently.

-

2)

Effectiveness: Recent evidence from 5 studies with over 3000 participants demonstrates that iCBT works in routine clinical practice in both primary care and specialist psychiatric settings.

-

3)

Safety: Routine measurement of outcome ensures that distress and severity is routinely assessed throughout iCBT courses. Both the patient and clinicians can be alerted of the possibility that additional help is needed. There are no reports of side effects or harms directly attributable to iCBT courses, although few studies have reported on adverse events during clinical trials of iCBT.

-

4)

Geographical reach: iCBT are especially suitable for people who cannot attend face-to-face sessions on a regular basis. This includes individuals in rural or remote areas, people with impaired mobility, those who work full-time, and those with inflexible work schedules.

-

5)

Acceptability and convenience: 85 % of participants in our RCTs of iCBT rate their experience of iCBT as “good to excellent,” and 9 out of 10 participants say they would recommend iCBT to a friend. iCBT courses can be successfully completed at a patient’s own pace in their own homes, and regularly revised as needed. iCBT courses can be successfully incorporated as part of stepped care model, allowing treating practitioners to monitor a larger caseload, at a fraction of the time and cost, freeing up time to spend providing treatment to the individuals who do not fully recover.

Conclusions

iCBT for anxiety disorders has been shown to be a powerful treatment, in both independently replicated clinical trials and in routine practice. iCBT results in large effect size reductions in anxiety and comorbid depression, with a NNT of 2. Further research is still needed to evaluate whether iCBT is of benefit to anxiety disorders secondary to substance use disorders, bipolar disorder, and psychosis. iCBT does not appear to generate side effects and the transparency of the system and the selective alerts mean that safety can be enhanced. iCBT can be regarded as a therapy enhancer and clinician extender [30] and is a powerful addition to a clinicians armamentarium.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: •• Of major importance

Kessler RC et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602.

Brown TA et al. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110(4):585–99.

Gøtzsche PC. Why I think antidepressants cause more harm than good. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:104–6.

Andersson G. Using the internet to provide cognitive behavior therapy. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47:175–80.

Andrews G et al. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13196.

Hedman E, Ljotsson B, Lindefors N. Cognitive behavior therapy via the Internet: a systematic review of applications, clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Expert Rev Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2012;12(6):745–64. A systematic review and meta analysis of the broader literature.

Mewton L et al. Current perspectives on Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with anxiety and related disorders. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2014;7:37–46. A very up to date systematic review of the field.

Nordgren LB et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of individually tailored internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for anxiety disorders in a primary care population: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2014;59:1–11.

Titov N et al. Internet treatment for social phobia reduces comorbidity. Aust N Z J Psychiatr. 2009;43(8):754–9.

Berger T, Boettcher J, Caspar F. Internet-based guided self-help for several anxiety disorders: a randomized controlled trial comparing a tailored with a standardized disorder-specific approach. Psychotherapy. 2014;51(2):207–19.

Mewton L, Wong N, Andrews G. The effectiveness of computerised cognitive behavioral therapy for generalised anxiety disorder in clinical practice. Depression Anxiety. 2012;29:843–9.

Newby JM et al. Effectiveness of transdiagnostic Internet cognitive behavioral treatment for mixed anxiety and depression in primary care. J Affect Disord. 2014;165:45–52.

Newby JM et al. Internet cognitive behavioral therapy for mixed anxiety and depression: a randomized controlled trial and evidence of effectiveness in primary care. Psychol Med. 2013;FirstView:1–14.

Bergstrom J et al. An open study of the effectiveness of Internet treatment for panic disorder delivered in a psychiatric setting. Nord J Psychiatry. 2009;63(1):44–50.

Hedman E et al. Effectiveness of Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for panic disorder in routine psychiatric care. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;128(6):457–67.

Ruwaard J et al. The effectiveness of online cognitive behavioral treatment in routine clinical practice. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40089.

Hedman E et al. Clinical and genetic outcome determinants of Internet- and group-based cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126(2):126–36.

Hedman E, Andersson G, Ljótsson B, Andersson E, Rück C, et al. Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy vs. cognitive behavioral group therapy for social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e18001. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018001.

Mewton L, Wong N, Andrews G. The effectiveness of internet cognitive behavioral therapy for generalized anxiety disorder in clinical practice. Depression Anxiety. 2012;29(10):843–9.

Titov N, Andrews G, Kemp A, Robinson E. Characteristics of adults with anxiety or depression treated at an internet clinic: comparison with a national survey and an outpatient clinic. PLoS One. 2011;5(5):e10885. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010885.

Sheehan D et al. The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(20):22–33.

First MB et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders (SCID-I). Washington: American Psychiatric Press; 1996.

Williams AD, Andrews G. The effectiveness of internet cognitive behavioral therapy (iCBT) for depression in primary care: a quality assurance study. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e57447.

Watts S, Newby JM, Mewton L, Andrews G. A clinical audit of changes in suicide ideas with internet treatment for depression. BMJ Open. 2012;2(5). doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001558.

Mewton L, Andrews G. Cognitive behavior therapy via the internet for depression: a useful strategy to reduce suicidal ideation. J Affect Disord. in press.

Rozental A et al. Consensus statement on defining and measuring negative effects of Internet interventions. Internet Interv. 2014;1:12–9. A discussion of the need to track and identify any side effects associated with iCBT.

Spek V et al. Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2007;37(03):319–28.

Andersson G, Carlbring P, Furmark T, on behalf of the S. O. F. I. E. Research Group. Therapist experience and knowledge acquisition in internet-delivered CBT for social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37411. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0037411.

Robinson E et al. Internet treatment for generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial comparing clinician vs. technician assistance. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e10942.

Andrews G, Williams AD. Up-scaling clinician assisted internet cognitive behavioral therapy (iCBT) for depression: A model for dissemination into primary care. Clin Psychol Rev. in press.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Alishia D. Williams declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Gavin Andrews is the developer of the ThisWayUpClinic suite of courses. They are a not for profit initiative of St Vincent's Hospital Sydney Australia. Dr Andrews has transferred all IP to the hospital.

Jill M. Newby is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Early Career Fellowship (1037787).

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Anxiety Disorders

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andrews, G., Newby, J.M. & Williams, A.D. Internet-Delivered Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Anxiety Disorders Is Here to Stay. Curr Psychiatry Rep 17, 533 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-014-0533-1

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-014-0533-1