Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review presents the current understanding of the role played by liver biopsy in the diagnosis and management of drug-induced liver injury (DILI).

Recent Findings

While liver biopsy remains an optional procedure in the evaluation of DILI, it has the potential to provide detailed information about the state of the liver. Recent histological surveys of DILI provide a framework for categorizing the patterns of injury that may be seen. Pattern information can be used to distinguish DILI from other potential causes of injury, both other acute injuries as well as pre-existing injury. The pattern of injury is related to differential diagnosis and in some cases can suggest a mechanism of injury. The character and severity of the injury could potentially be used in clinical decision-making. Examples of the use of liver biopsy in the context of DILI encountered in clinical trials are provided which highlight these points.

Summary

Liver biopsy may be a useful tool in DILI evaluation, particularly in complex clinical situations and clinical trials with experimental therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The liver biopsy occupies a unique position in the evaluation of drug-induced liver injury (DILI). Unlike the evaluation of chronic viral hepatitis, in which liver biopsy has a well-defined role in staging and grading, there is no specific role for liver biopsy in DILI. Instead, obtaining a liver biopsy during the clinical evaluation of DILI enlists the pathologist as an expert consultant who can interpret the histological changes in light of the patient’s clinical history and laboratory evaluation. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) position paper on liver biopsy does not specifically address the use of liver biopsy in DILI, but it does highlight the general use of the biopsy in situations where multiple parenchymal disease may be present, there are abnormal liver tests or fevers of unknown etiology, or when there are unexplainable imaging abnormalities [1]. Each one of these may apply in certain cases of suspected DILI. EASL guidelines for DILI recommend consideration of biopsy in three situations: to support diagnosis of DILI or an alternate, to help in the evaluation of DILI where serology is suggestive of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) and when injury persists longer than expected to inform management decisions and provide prognostic information. The AASLD and EASL guidelines provide complementary approaches since they look at the value of liver biopsy from different points of view. They also highlight the paucity of clinical evidence surrounding the use of the liver biopsy in the diagnosis and management of DILI.

Initial Biopsy Evaluation—Defining the Pattern

The pathologist must assess several aspects of the histological changes to provide the best assistance to the clinical team (Table 1). The evaluation may begin prior to the actual liver biopsy procedure, with a communication from the clinical team that a biopsy is being performed to evaluate suspected DILI. Although most histological questions can be addressed using a formalin-fixed specimen, some evaluations may require alternate techniques. Ultrastructural examination for evidence of mitochondrial injury requires glutaraldehyde fixation for best results and may need to be sent out to a specialty lab as many pathology departments no longer maintain diagnostic electron microscopy. Fat stains, such as oil red O, require sectioning of the biopsy on a cryostat prior to processing. Arrangements for these types of special handling should be made prior to obtaining the liver biopsy.

Initial review of the biopsy should be unbiased and focused on identification of the pattern of injury, as outlined below. The liver, like many organs, has a limited number of stereotypical responses to insults. These form the basis of histological differential diagnosis. Individual patterns may have nuances that allow weighting of the differential diagnosis. For example, both chronic hepatitis C and autoimmune hepatitis share the chronic hepatitic pattern of injury, but autoimmune hepatitis is more likely to have prominent plasma cells infiltrates, particularly at the parenchymal interface. Most of the determination of DILI causality will be based on the pattern of injury and nuances that relate to certain drugs or other diseases that need to be excluded from consideration. The pattern of injury may raise additional questions relating to alternate explanations of injury that require further testing. This is especially true of disease entities that are uncommon. For example, the hepatitis associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has a pattern of injury that is superficially similar to chronic hepatitis, but with the nuance of sinusoidal infiltrates [2]. This “mononucleosis pattern” has been described in DILI, particularly with phenytoin and possibly others, like dapsone, but recognition of this pattern should prompt viral testing for EBV [3, 4].

Classification of injury in hepatotoxicity has been addressed by several survey studies (Table 2). In one of the earliest studies, Popper et al. classified hepatotoxic injury into six histopathological categories: zonal injury (zone 3 necrosis often with steatosis), uncomplicated cholestasis (centrilobular cholestasis without other abnormalities), non-specific (i.e., non-viral) hepatitis with or without cholestasis, viral hepatitis-like (which was further subdivided into spotty necrosis, extensive zonal necrosis, and massive necrosis), non-specific reactive hepatitis and steatosis [5]. Out of 155 cases in this early study, most were classified as either non-specific hepatitis with cholestasis or the massive necrosis subcategory of the viral hepatitis-like injury. After this study, histopathological classifications of hepatotoxicity were mainly to be found in book chapters and reviews of the pathology of DILI. However, in 2014, the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) published a histopathological survey of 249 cases of suspected DILI, using a classification derived from the classification put forward by Drs. Ishak and Zimmerman in Dr. Zimmerman’s textbook of DILI [6]. This classification included pattern-based categories dominated by necroinflammation, cholestasis, steatosis, or vascular injury [7]. Additional categories were included for biopsies showing minimal changes or complex pathology with two or more patterns of injury. In the DILIN cohort, the most common categories observed were acute and chronic hepatitis, cholestatic hepatitis, and acute and chronic cholestasis, which together accounted for 84% of the cases. Wang et al. made use of the DILIN classification in their evaluation of 590 cases of DILI from China [8••]. They reorganized the classification to focus on targets of injury, specifically hepatocytes, bile ducts, and vessels. Although their largest number of cases remained in the acute (lobular) hepatitis category, 9% of the cases showed vascular injury as the main finding. The authors attributed this observation to differences between Chinese and Western populations with respect to herbal medications and contaminants (particularly arsenic). It seems clear that the distribution of injury patterns that might be prevalent in different populations may vary depending on differences in medication exposure. Although drugs have been implicated in tumorigenesis, none of these classifications include categories for tumors for practical reasons.

Character and Severity of Injury Provide Additional Information

Once the pattern of injury is addressed, additional information on the character and severity of the injury can be described. Both can be used to guide clinical management although research into translation of liver biopsy findings to clinical decisions is lacking. The character of the injury refers to the specific elements that may be present, particularly with respect to the inflammatory infiltrate. An injury that is rich in inflammatory cells, particularly plasma cells, lymphocytes, and granulomas, may suggest a benefit from therapeutic immunosuppression. On the other hand, injury that is more structural in character, such as vascular obstruction, bile duct loss, or fibrosis, may respond poorly to therapies directed at the immune system.

Severity of the injury has been linked to outcome with certain histological changes. Extensive necrosis has been linked to poor outcome in several studies [7, 9,10,11]. Ductular reaction, which is a proliferation of hepatic progenitor cells and may represent an ineffective response to replicative failure in hepatocytes [12], has also been noted to relate to poor outcome [7, 13]. Microvesicular steatosis, often the result of mitochondrial injury, was associated with acute liver failure and death in the series from the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network (DILIN) even though only one case of pure microvesicular steatosis was identified [7]. This suggests that in DILI, even focal areas of microvesicular steatosis may be a marker of significant hepatocellular injury which is not true when the same observation is made in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis [14].

The character of the inflammation has also been linked to milder injury with better prognosis. These include eosinophils and granulomas [7, 10], both of which are features of immunoallergic immune responses [15]. On occasion, the biopsy may show mild, non-specific findings, despite persistently abnormal biochemical tests. After careful exclusion of subtle vascular injury patterns and changes indicating recovery from acute hepatitis [16•], consideration can be given to cautious continuation of a beneficial medication. Such clinical decision-making has been formalized for methotrexate, where it is acceptable to continue administration of the drug until hepatic fibrosis reaches the stage of bridging. Some of these cases may represent the histological equivalent of adaptation, in which the liver experiences mild injury on the way to developing tolerance to the drug [17].

Some patients experience prolonged biochemical injury after stopping the suspect medication. This may suggest that the suspect drug is not at fault and further work-up is necessary to identify the cause of the patient’s abnormal laboratory tests. However, the concept of “chronic DILI,” in which the biochemical injury from a drug lasts for 6–12 months or more is accepted. Such patients tend to be older and have cholestatic presentations of liver enzymes [18]. Biopsies taken after 12 months of injury showed patterns of chronic liver disease, including chronic cholestasis (60%), chronic hepatitis (20%), and steatohepatitis (20%). Progression of fibrosis between initial biopsy and follow-up was seen in 8/15 patients [18]. Only one patient showed regression of fibrosis. In the case that regressed, the implicated drug was tamoxifen, and there was resolution of steatohepatitis in the follow-up biopsy along with disappearance of the fibrosis [18]. Six of the 15 patients had new evidence of duct loss on the follow-up biopsy, suggesting that vanishing bile duct syndrome could be a late effect of drug injury as well as an acute finding [19•].

Liver Biopsy in Clinical Trials

Liver biopsy may be helpful in evaluating cases of liver injury in the context of clinical trials. When an experimental agent is being tested and liver injury is detected, there is often little information in the literature that can be used to decide whether DILI has occurred. As noted above, a liver biopsy can provide insight into many aspects of the injury and may uncover other reasons for liver injury. Two examples of the use of liver biopsy in clinical trial situations are reviewed.

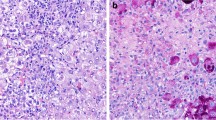

In 1993, the National Institutes of Health conducted a phase 2 trial of fialuridine in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Although the protocol called for 6 months of therapy, the trial was terminated on an emergency basis after 13 weeks when one of the patients developed hepatic failure and lactic acidosis [20]. In two patients, the hepatic failure was rapidly progressive, and they underwent liver transplantation. Tissue from explants was rush processed for frozen section oil red O staining, routine light microscopy and ultrastructural evaluation. The sections showed diffuse microvesicular steatosis in addition to residual chronic hepatitis B (Fig. 1a) [21]. Ultrastructural examination revealed severe, diffuse mitochondrial injury, with marked swelling and loss of the cristae (Fig. 1b). Additional findings underscoring hepatocellular injury were marked glycogen depletion, consistent with anaerobic metabolism and marked ductular reaction, consistent with replicative failure of hepatocytes. Although in this case, tissue was obtained through transplantation rather than a needle biopsy, a wealth of information on the toxicity was available within a few days. The histological findings unequivocally confirmed that hepatocellular mitochondrial injury was responsible for the hepatic failure and that the underlying liver disease played little or no role. Similar injury patterns had been previously identified zidovudine and didanosine, suggesting a class effect of certain types of nucleoside analogues, and follow-up studies demonstrated disruption of mitochondrial DNA replication with gradual loss of mitochondrial DNA [22,23,24].

Examples of DILI from clinical trials. a Microvesicular steatosis due to fialuridine (H&E, × 400). b Mitochondrial injury from fialuridine. Mitochondria (*) are enlarged and show loss of cristae. Microvesicular steatosis (#) is also present (× 6000). c Acute hepatitis with panlobular inflammation due to ipilimumab (H&E, × 200). d Bile duct injury (arrow) due to ipilimumab (H&E, × 600). e Central vein endothelialitis (arrow) due to ipilimumab (Masson trichrome, × 600). f Severe acute hepatitis with bridging necrosis due to pembrolizumab (H&E, × 40)

The immune-related toxicity of checkpoint inhibitors provides a more recent example of the use of liver biopsy in clinical trials. Checkpoint inhibitors are a class of drugs that block receptors on T lymphocytes, preventing them from receiving signals that inhibit activation. While the goal of therapy is to overcome the inhibition of inflammatory responses induced by a malignancy, one of the consequences of therapy is the development of autoimmune injury in other parts of the body [25•]. Checkpoint inhibitors have been developed that target the cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4), the programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1), and the ligand of PD-1 (PD-L1). Early phase clinical trials of the first checkpoint inhibitor, ipilimumab, an anti-CTLA-4 antibody, identified a number of off-target autoimmune injuries, including the liver [26]. Five cases of hepatitis with liver biopsies taken during clinical trials were later gathered together and published [27]. All five cases showed an acute hepatitis pattern of injury (Fig. 1c–e), which excluded the possibility of an acute exacerbation of underlying idiopathic autoimmune hepatitis. The index case (case 5) showed acute hepatitis superimposed on pre-existing steatohepatitis, demonstrating the ability of liver biopsy to identify and separate patterns of injury from distinct etiologies. Subsequent publications of histological injury from checkpoint inhibitors confirmed and extended these observations. Ipilimumab with or without the addition of nivolumab (a PD-1 inhibitor) has been associated with acute hepatitis patterns, often with centrilobular accentuation and central vein endothelitis [28]. Granulomas, including fibrin-ring granulomas, have been reported with combination ipilimumab-nivolumab therapy [29]. Most recently, Zen and Yeh have reported bile duct injury with bile duct paucity in a patient treated with nivolumab alone [30••]. They also evaluated the lymphocyte infiltrates in checkpoint inhibitor injury and demonstrated that there were far fewer B lymphocytes and CD4-positive T lymphocytes than in comparable cases of autoimmune hepatitis. While biopsy data from hepatic injury due to other checkpoint inhibitors is limited, a recent case report of hepatitis from pembrolizumab (a PD-1 inhibitor) demonstrated duct and vascular injury along with an acute hepatitis with necrosis [31]. While it could be argued that the diagnosis of immune-related injury in the liver would not require a liver biopsy, the pathological changes have demonstrated that the immune targets include duct epithelial and endothelial cells as well as hepatocytes and that the immune reaction is different from idiopathic autoimmune hepatitis. These findings would not be apparent without examining the tissue.

Conclusion

In 1974, an international group of expert hepatic pathologists and hepatologists offered guidelines for the diagnosis of DILI, focusing mainly on the use of the liver biopsy [32]. They suggested five uses of the liver biopsy in DILI: (1) Evaluating suspected DILI from an essential medicine by ruling out the presence of underlying liver disease as the etiology; (2) When options exist for the use of alternate medications the presence of DILI lesions on biopsy might spur the use of the alternates; (3) Exclusion of mechanical biliary obstruction as the cause of the injury; (4) In unexplained liver disease, the pattern of injury might suggest a drug etiology; (5) When liver injury occurs in clinical trials, a biopsy may help differentiate between DILI caused by the new drug and other etiologies. Although laboratory testing and imaging have supplanted the use of the biopsy for some of these indications, the general principles listed in 1974 remain. The biopsy may be used to help differentiate between multiple possible injuries, identify contributions of underlying disease, and assist in clinical decision-making and in clinical trial situations when there may be additional questions about the liver injury. Pathologists with specialty expertise in liver disease understand the spectrum of histological liver injury from multiple common and uncommon etiologies and therefore may serve as valuable clinical consultants when questions remain about the status of the liver in clinical practice.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Rockey DC, Caldwell SH, Goodman ZD, Nelson RC, Smith AD. American Association for the Study of Liver D. Liver biopsy. Hepatology. 2009;49(3):1017–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22742.

Suh N, Liapis H, Misdraji J, Brunt EM, Wang HL. Epstein-Barr virus hepatitis: diagnostic value of in situ hybridization, polymerase chain reaction, and immunohistochemistry on liver biopsy from immunocompetent patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(9):1403–9.

Mullick FG, Ishak KG. Hepatic injury associated with diphenylhydantoin therapy. A clinicopathologic study of 20 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1980;74(4):442–52.

Uetrecht J, Zahid N, Shear NH, Biggar WD. Metabolism of dapsone to a hydroxylamine by human neutrophils and mononuclear cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;245(1):274–9.

Popper H, Rubin E, Cardiol D, Schaffner F, Paronetto F. Drug-induced liver disease: a penalty for progress. Arch Intern Med. 1965;115:128–36.

Zimmerman HJ. Hepatotoxicity: the adverse effects of drugs and other chemicals on the liver. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 1999.

Kleiner DE, Chalasani NP, Lee WM, Fontana RJ, Bonkovsky HL, Watkins PB, et al. Hepatic histological findings in suspected drug-induced liver injury: systematic evaluation and clinical associations. Hepatology. 2014;59(2):661–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26709.

•• Wang T, Zhao X, Shao C, Ye L, Guo J, Peng N, et al. A proposed pathologic sub-classification of drug-induced liver injury. Hepatol Int. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-019-09940-9 Adds a new histologic classification system that may be better fitted for DILI cases from Asia .

Philips CA, Paramaguru R, Joy AK, Antony KL, Augustine P. Clinical outcomes, histopathological patterns, and chemical analysis of Ayurveda and herbal medicine associated with severe liver injury-a single-center experience from southern India. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2018;37(1):9–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12664-017-0815-8.

Bjornsson E, Kalaitzakis E, Olsson R. The impact of eosinophilia and hepatic necrosis on prognosis in patients with drug-induced liver injury. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(12):1411–21.

Ndekwe P, Ghabril MS, Zang Y, Mann SA, Cummings OW, Lin J. Substantial hepatic necrosis is prognostic in fulminant liver failure. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(23):4303–10. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i23.4303.

Kaur S, Siddiqui H, Bhat MH. Hepatic progenitor cells in action: liver regeneration or fibrosis? Am J Pathol. 2015;185(9):2342–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.06.004.

Katoonizadeh A, Nevens F, Verslype C, Pirenne J, Roskams T. Liver regeneration in acute severe liver impairment: a clinicopathological correlation study. Liver Int. 2006;26(10):1225–33.

Tandra S, Yeh MM, Brunt EM, Vuppalanchi R, Cummings OW, Unalp-Arida A, et al. Presence and significance of microvesicular steatosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2011;55(3):654–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2010.11.021.

Ishak KG, Zimmerman HJ. Drug-induced and toxic granulomatous hepatitis. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1988;2(2):463–80.

• Czeczok TW, Van Arnam JS, Wood LD, Torbenson MS, Mounajjed T. The almost-normal liver biopsy: presentation, clinical associations, and outcome. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41(9):1247–53. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000881 Careful examination of the etiological challenges presented by biopsies with minimal findings .

Dara L, Liu ZX, Kaplowitz N. Mechanisms of adaptation and progression in idiosyncratic drug induced liver injury, clinical implications. Liver Int. 2016;36(2):158–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.12988.

Fontana RJ, Hayashi PH, Barnhart H, Kleiner DE, Reddy KR, Chalasani N, et al. Persistent liver biochemistry abnormalities are more common in older patients and those with cholestatic drug induced liver injury. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(10):1450–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2015.283.

• Bonkovsky HL, Kleiner DE, Gu J, Odin JA, Russo MW, Navarro VM, et al. Clinical presentations and outcomes of bile duct loss caused by drugs and herbal and dietary supplements. Hepatology. 2017;65(4):1267–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28967 Detailed description of histology and clinical outcomes for vanishing bile duct syndrome due to DILI.

McKenzie R, Fried MW, Sallie R, Conjeevaram H, Di Bisceglie AM, Park Y, et al. Hepatic failure and lactic acidosis due to fialuridine (FIAU), an investigational nucleoside analogue for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(17):1099–105.

Kleiner DE, Gaffey MJ, Sallie R, Tsokos M, Nichols L, McKenzie R, et al. Histopathologic changes associated with fialuridine hepatotoxicity. Mod Pathol. 1997;10(3):192–9.

Freiman JP, Helfert KE, Hamrell MR, Stein DS. Hepatomegaly with severe steatosis in HIV-seropositive patients. Aids. 1993;7(3):379–85.

Lai KK, Gang DL, Zawacki JK, Cooley TP. Fulminant hepatic failure associated with 2′,3′-dideoxyinosine (ddI). Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(4):283–4.

Lewis W, Levine ES, Griniuviene B, Tankersley KO, Colacino JM, Sommadossi JP, et al. Fialuridine and its metabolites inhibit DNA polymerase gamma at sites of multiple adjacent analog incorporation, decrease mtDNA abundance, and cause mitochondrial structural defects in cultured hepatoblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(8):3592–7.

• Palmieri DJ, Carlino MS. Immune checkpoint inhibitor toxicity. Curr Oncol Rep. 2018;20(9):72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-018-0718-6 Comprehensive summary of systemic immune-related adverse events across the spectum of checkpoint inhibitors .

Phan GQ, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Hwu P, Topalian SL, Schwartzentruber DJ, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity induced by cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(14):8372–7.

Kleiner DE, Berman D. Pathologic changes in ipilimumab-related hepatitis in patients with metastatic melanoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(8):2233–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-012-2140-5.

Johncilla M, Misdraji J, Pratt DS, Agoston AT, Lauwers GY, Srivastava A, et al. Ipilimumab-associated hepatitis: clinicopathologic characterization in a series of 11 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39(8):1075–84. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000453.

Everett J, Srivastava A, Misdraji J. Fibrin ring granulomas in checkpoint inhibitor-induced hepatitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41(1):134–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000759.

•• Zen Y, Yeh MM. Hepatotoxicity of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a histology study of seven cases in comparison with autoimmune hepatitis and idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury. Mod Pathol. 2018;31(6):965–73. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-018-0013-y Provides histologic description of a growing class of agents that can cause DILI felt to be immune mediated.

Aivazian K, Long GV, Sinclair EC, Kench JG, McKenzie CA. Histopathology of pembrolizumab-induced hepatitis: a case report. Pathology. 2017;49(7):789–92.

Guidelines for diagnosis of therapeutic drug-induced liver injury in liver biopsies. Lancet. 1974;1(7862):854–7.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Kleiner prepared the manuscript, including all figures and tables.

Funding

This review was financially supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

David E. Kleiner declares no potential conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Drug-Induced Liver Injury

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kleiner, D.E. The Role of Liver Biopsy in Drug-Induced Liver Injury. Curr Hepatology Rep 18, 287–293 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11901-019-00486-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11901-019-00486-w