Abstract

Purpose of Review

Crohn’s Disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory disease that can lead to progressive damage to the gastrointestinal tract and significant disability. Early, “top-down” biologic therapy is recommended in moderate-to-severe CD to induce remission and to prevent hospitalization and complications. However, an estimated 20–30% of patients with CD have a mild disease course and may not garner sufficient benefit from expensive, immunosuppressing agents to justify their risks. Herein, we review characteristics of patients with mild CD, the available options for disease treatment and monitoring, and future directions of research.

Recent Findings

For ambulatory outpatients with low-risk, mild, ileal or ileocolonic CD, induction of remission with budesonide is recommended. For colonic CD, sulfasalazine is a reasonable choice, although other aminosalicylates have no role in the treatment of CD. No large, randomized trial has supported the use of antibiotics or antimycobacterials in the treatment of CD. Partial Enteral Nutrition and Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diets may be appropriate for inducing remission in some adult patients, with trials ongoing. Select patients with mild-to-moderate CD may benefit from maintenance therapy with azathioprines or gut specific biologics, such as vedolizumab. The role of complementary and alternative medicine is not well defined.

Summary

The identification, risk stratification, and monitoring of patients with mild CD can be a challenging clinical scenario. Some patients with low risk of disease progression may be appropriate for initial induction of remission with budesonide or sulfasalazine, followed by close clinical monitoring. Future research should focus on pre-clinical biomarkers to stratify disease, novel therapies with minimal systemic immune suppression, and validation of rigorous clinical monitoring algorithms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Crohn’s Disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory disease that can lead to progressive damage to the gastrointestinal tract and significant disability [1••, 2]. Up to 80% of patients with CD will have at least one lifetime hospitalization, with significant costs related to medications, hospitalizations, and lost productivity [3]. Although CD has increasingly been recognized as a progressive disease in which early intervention is needed to prevent complications, an estimated 20–30% of patients with CD have a mild disease course, with stable disease location, no complications, and mild disease activity [1••]. Herein we review current recommendations and data on mild CD, a common but understudied area of inflammatory bowel disease.

Definition of Mild CD

Society guidelines have proposed varied definitions of mild CD. For example, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines characterize patients with mild CD as those with mild endoscopic activity (Simple Endoscopic Score-CD [SES-CD] 3–6 or CD Endoscopic Index of Severity [CDEIS] 3–9 ([4]), tolerating a diet, < 10% weight loss, and able to be treated as outpatients without fever, tachycardia, severe abdominal pain, or obstructive symptoms. European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) guidelines define mild Crohn’s Disease as low-risk for 5-year disabling disease, lacking such features as perianal disease, ileocolonic location, young age at diagnosis, or any flare requiring treatment with systemic steroids [5]. The American Gastrointestinal Association draws similar distinctions, further defining a Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI, which uses weight, daily number of loose stools, abdominal pain, sex, antidiarrheal use, and general well-being as metrics) of 150–220 as the definition of mild CD [6].

The benefit of timely escalation to biologic therapies has been demonstrated among patients with moderate-to-severe CD [7], but given the costs and risks (including infection, malignancy, and infusion reactions) associated with biologic therapies, identifying these patients at low risk of progressive disease is of critical importance. Thus, guidelines consider both disease activity at diagnosis and low-risk features within their diagnostic paradigms. The ACG and AGA suggest the following features that typify patients with CD at low risk for progression: older age at diagnosis (> 30 years); limited extent of disease; superficial ulcers (rather than deep or penetrating disease); no penetrating or stricturing disease behavior; no prior surgeries; and no perianal or severe rectal disease [1••, 6].

Critically, among patients with mild CD on presentation, retrospective studies suggest that 46–57% continue to have mild disease at 5–15 year follow-up [8,9,10,11]. Further, a recent meta-analysis highlighted the low prevalence (1.6%) and low risk of progression of incidentally diagnosed terminal ileitis among asymptomatic patients undergoing screening ileocolonoscopy for colorectal cancer [12]. Such clinical stratification tools are invaluable to the gastroenterologist closely monitoring patients with mild CD.

Overview of an Approach to Management and Monitoring of Mild CD

In these low-risk patients with mild disease, ACG guidelines recommend an attempt to induce remission with a budesonide taper not exceeding 4 months’ duration, followed by endoscopic, enterographic, and biochemical monitoring for disease progression [1••]. Limited data support a potential role for sulfasalazine, but no other 5-aminosalicylate therapies, in isolated colonic CD. After budesonide induction of remission, maintenance therapy with thiopurines may be warranted and efficacious in relapsing or moderately active patients. However, it is not clear that all patients with mild CD require maintenance therapy. A meta-analysis of 28 large, randomized controlled trials investigating the placebo response rate after induction of remission for mild, moderate, and severe Crohn’s Disease estimated a remission rate of 17% among the placebo groups [13]. After an initial course of systemic steroids, 32–38% of patients with mild CD in two inception cohorts remained in steroid-free remission at 12 months after initial induction [14, 15].

The ACG guidelines specifically affirm the acceptability of rigorous monitoring after induction of remission in mild CD. Treatment that is more targeted to symptomatic relief (dietary manipulation, anti-diarrheal mediations, etc.) is a reasonable approach in mild CD. If patients elect to pursue close surveillance after induction of remission, biochemical monitoring with endoscopic evaluation and inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)), fecal calprotectin (FCP), and other surrogate markers of inflammation should be pursued, although the role and timing of monitoring that is proactive or reactive to symptoms remains unclear. Some studies have shown benefit to tight disease control and potential therapeutic escalation via biochemical monitoring every 3 months, although these markers may be less accurate in mild disease [7].

Ileal-Release Budesonide for Mild Ileocecal CD

With a strong recommendation from the ACG and ECCO, ileal-release budesonide (Entocort) is the preferred agent for induction of remission for mild ileocecal CD [1••, 16••]. Dosing begins at 9 mg daily and should be tapered over no more than 4 months to induce remission. A meta-analysis of the existing three RCTs comparing budesonide 9 mg daily with placebo among patients with active disease and average CDAIs in the “moderate” CD activity range showed superior relative rates of 8-week clinical remission in the budesonide group (1.93, 95% confidence interval 1.37–2.73), with ~ 50% of all treated patients achieving clinical remission [17,18,19,20]. Additional benefits of budesonide compared with other induction agents, including 5-aminosalicylates (ASAs) and systemic glucocorticoids, include a favorable safety profile, with significant first-pass hepatic metabolism that mitigates many deleterious effects of systemic glucocorticoids. Neither ileal budesonide nor prednisone are good options to maintain clinical remission in CD [14]. Among patients who achieve clinical remission with budesonide induction, ongoing maintenance therapy with budesonide 6 mg daily did not have significant benefit over placebo at 3, 6, or 12 months follow-up, with 55% of patients receiving budesonide 6 mg and 48% of patients receiving placebo remaining in remission at 12 months [20]. Therefore, we recommend the following induction course for patients with low-risk, mild: 2 months of Entecort 9 mg daily, followed by 1 month of Entecort 6 mg daily and a final month of Entecort 3 mg daily. As above, clinical symptoms, inflammatory biomarkers, and fecal calprotectin should be trended thereafter.

Sulfasalazine for Mild Colonic CD

Aminosalicylates are widely prescribed for CD (up to 60% of patients in one study, used for an average of 28 months) [21]. However, ACG and ECCO guidelines strongly recommend against the use of oral mesalamine to treat patients with active CD given inconsistent evidence that it carries any benefit in achieving clinical remission at 12 months over placebo [1••, 16••, 22]. A Cochrane Review included 2,367 patients and found no benefit of 1-4 g/day mesalamine to induce clinical response or remission [22]. Two studies have compared high-dose mesalamine to budesonide as induction therapy for active CD – one demonstrating equivalent results [23] in mildly active CD, including colonic and ileal CD; the other, with budesonide showing significantly higher clinical remission at 16 weeks (62% budesonide group vs. 36% mesalamine group) among patients with ileocecal CD [24].

In a meta-analysis analyzing the subgroup of patients with Crohn’s colitis, sulfasalazine did have a significantly higher rate of inducing remission, at 45% compared to 29% of placebo-treated patients at 18 weeks (RR1.38, 95% CI 1.00–1.89) [22]. Among the aminosalicylates, sulfasalazine has less first-pass jejunal absorption, allowing enhanced colonic delivery of the 5-ASA active moiety after enzymatic reduction by the colonic microbiota [25]. Still, systemic steroids were superior at inducing remission (60% of patients), albeit with a less desirable safety profile compared to sulfasalazine.

Immunomodulators to Maintain Remission in Mild CD

Immunomodulators, including azathioprine (1.5–2.5 mg/kg daily) and 6-MP (0.75–1.5 mg/kg daily), remain indicated for patients with active CD during monitoring after initial response to induction therapy or for patients who remain steroid-dependent. Methotrexate is another option that can be considered (up to 25 mg weekly, IM or SC) to improve symptoms and reduce steroid dependence in active CD [26]. Neither agent is effective in inducing steroid-free remission in CD [1••, 16••].

Compared to no therapy, the use of azathioprine for maintenance of remission in mild CD had a number needed to treat (to prevent one relapse) of 9 [27]. Compared to budesonide maintenance therapy (which is not recommended), a small RCT found significantly higher clinical remission or response in azathioprine-treated patients (83% vs. 24% of budesonide alone) [28]. Compared to biologic agents, thiopurines have similar infection and malignancy risks [29]; however, leukopenia (up to 5% of patients), hepatitis, pancreatitis, non-melanoma skin cancer, infection, and other cytopenias are noted side effects that may limit their long-term use. Thiopurines have a markedly higher risk of serious adverse events (relative risk of 9.37, although with a wide 95% CI 1.84–47.7) compared to 5-ASAs [27].

Assorted Therapies without Any Clear Role in Mild CD

ACG guidelines recommend against the use of certain immunosuppressant medications (cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus); fecal microbiota transplant; probiotics; and antibiotics (including metronidazole, combination therapy with ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, and hydroxychloroquine, and antimycobacterial therapies) in mild CD [1••, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34]. Despite our current guidelines, some promising open-label, preliminary results exist for extended-release rifaximin, low-dose naltrexone, and THC in the treatment of mild-to-moderate CD. In 16 patients given extended-release Rifaximin, 62% of treated and 43% of controls achieved clinical remission [35]. Among patients treated with 12 weeks of low-dose naltrexone, 30% achieved clinical remission vs. 16% of controls [36]. Preliminary data have been published on 16 patients with mild-to-moderate CD treated with high-dose Rifaximin with promising findings that remain to be evaluated in randomized, controlled trials [35]. A small randomized, controlled trial investigating CBD-rich oral cannabis found improved CDAI and quality of life, but no biochemical or endoscopic improvement, among treated patients with mild-to-moderate Crohn’s disease [37].

Diet: from Exclusive Enteral Nutrition to the CD Exclusion Diet

Among the pediatric population, exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN) delivered via nasogastric tube is a well-established option for induction of remission in mild CD, with a 73% combined remission rate for EEN in pediatric CD [38]. After an initial 6- to 12-week dietary trial, children slowly reintroduce solid foods under the supervision of a multidisciplinary team, including dieticians, psychologists, and gastroenterologists. Patient tolerance of exclusive nasogastric feeds can be limited, and non-adherence to the dietary plan predicts failure to achieve remission [39].

There is increasing interest in the Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diet (CDED), a whole foods diet devised to minimize pro-inflammatory stimuli that is used alongside oral supplementation with partial enteral nutrition (PEN). Compared to EEN, CDED + PEN was significantly better tolerated among 74 randomized pediatric patients (74% vs. 98%, p = 0.002). Both interventions were effective in achieving steroid-free clinical remission with improved C-reactive protein levels at 6 and 12 weeks (59% vs. 75%; 45% vs 75%, EEN vs. CDED) [40]. Given the superior safety profile of both dietary approaches compared to corticosteroid, immunomodulator, and biologic therapies, nutritional strategies are often first-line to induce remission among children with mild CD.

Accordingly, Yanai et al. published promising pilot data investigating a 24-week trial of CDED vs. CDED + PEN among 44 adult, bionaive patients with mild CD and endoscopic or biochemical evidence of active inflammation. Clinical remission (Harvey-Bradshaw Index < 5) was achieved at week 6 by 68% and 57% of patients in the CDED + PEN group vs. CDED group, 80% of whom sustained clinical remission at week 24. Endoscopic remission at week 24 was sustained by 35% of patients (in either group) [41•].

Another larger, randomized trial (DINE) compared the Specific Carbohydrate Diet (grain-free, lactose-free, specific legumes and starches, and all only unprocessed foods) to a Mediterranean Diet (high in fruits, vegetables, fish, whole rains, and olive oil) among 194 adults with mild symptoms related to CD [42]. Notably, 57% of these patients were on biologic therapies and 40% of patients had complicated disease. Neither diet was superior at 12 weeks, with relatively high symptomatic response to both diets (43–46%). The impact on objective inflammation markers was less marked, with a CRP response in only 3–5%, although ~ 30% of patients had a decrease in fecal calprotectin in both groups. The authors concluded that the ease and other validated health benefits to the Mediterranean Diet (decreased risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and systemic inflammation) may favor its recommendation to patients with mild CD, although no clear comparison to CDED + PEN or specific utility as induction therapy exists to date. Other anti-inflammatory diets, including the “IBD-AID” diet modulating fatty acids, limiting certain carbohydrates, and including pre- and pro-biotic foods, reduced medication requirement while improving quality of life among patients with CD. However, only 11 patients completed the study, with 70% dietary compliance [43].

Complementary and Alternative Medical (CAM) Treatments

A systematic review of available CAM treatments uncovered significant heterogeneity in all available trials but found the best evidence for wormwood and acupuncture in maintenance of remission in mild CD [44]. None of the agents described below have rigorously been shown to induce remission in patients with CD, so we would not advocate their formal recommendation at this point. However, some patients may wish to try CAM, so understanding the possible options is helpful.

Clinical investigations into wormwood have used discrepant dosing strategies, included small numbers of patients with unrealistically low placebo response rates (0%), and lack critical safety data, given its known dose-dependent neurotoxicity [45, 46]. Highly active curcumin has a favorable safety profile and may be effective in maintaining remission in mild ulcerative colitis [47]. Limited data in few patients have similarly shown modest symptomatic benefit for the treatment of mild CD [48].

Multiple potential benefits of acupuncture and moxibustion may relate to CD, ranging from management of illness-related stress, anxiety, and fatigue to even disease-modifying benefits [49, 50, 51]. Unfortunately, the studied acupuncture and moxibustion approaches described in the literature are heterogenous. Still, a recent study of three weekly sessions over 12 weeks compared to a sham procedure demonstrated a higher clinical remission rate (60% vs. 20%), lower CDAI, CRP, and CDEIS, and improved microbial diversity in the acupuncture group [52].

Conclusion and Directions for Future Research

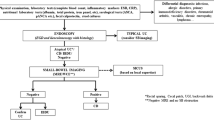

The available evidence for the management of mild CD supports a trial of induction therapy with budesonide for ileocolic CD, with sulfasalazine for colonic CD, or with systemic steroids. After completing and responding to induction therapy, gastroenterologists should engage in shared decision-making with their patients with mild CD activity and low risk of complicated disease. Thiopurines are the best-studied immunomodulating agents to maintain remission in mild CD, although their safety profile can be restrictive to some patients. Newer classes of biologics, such as anti-integrins (vedolizumab) and anti-interleukins (ustekinumab, Risankizumab), should be considered and discussed with these patients, as these biologics are highly efficacious and have favorable side effect profiles compared to both immunomodulators and to TNF-alpha inhibitors. Careful clinical and objective monitoring (with serial biochemical tests, endoscopy, and enterography) may be reasonable for patients who choose to trial no therapy or to pursue acupuncture, herbal supplementation, or dietary therapies under the guidance of an interdisciplinary team. Early evidence supports careful implementation of dietary interventions to induce remission among motivated patients (Fig. 1).

Approach to Mild Crohn’s Disease. CD: Crohn’s Disease. AZA: Azathioprine,1.5–2.5 mg/kg daily; 6-MP: 6-mercaptopurine, 0.75–1.5 mg/kg daily; MTX: methotrexate, up to 25 mg IM or SQ weekly; VDZ: vedolizumab; UST: ustekinumab; RIS: Risankizumab. * = for motivated patients, can trial Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diet ± Partial Enteral Nutrition to induce remission, irrespective of extent

More precise tools using genetic strategies, metabolomic profiles, and microbial signatures are needed to identify these patients with mild CD who are appropriate for such “watch-and-wait” guidance. Ideally, algorithms should be developed that identify pre-diagnostic metabolomic perturbances in genetically susceptible individuals, allowing for prevention of Crohn’s Disease, or at least moderation of high-risk disease phenotypes [53]. Pharmaceutical development of novel, safe therapeutic options for patients with mild CD is needed. Large, rigorously conducted trials should aim to craft reasonable treatment strategies for patients with mild, low-risk CD, for whom less may truly be more.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

•• Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV, Isaacs KL, Regueiro MD, Gerson LB, Sands BE. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Crohn’s Disease in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:481–517. These revised guidelines incorporate recent evidence against the previously prevalent role of mesalamines and antibiotics in the treatment of mild-to-moderate Crohn's Disease, excluding higher-risk patients with perianal disease who do require antibiotic therapy. Close monitoring with symptomatic management is described as a reasonable alternative for patients after induction of remission.

Agrawal M, Spencer EA, Colombel J-F, Ungaro RC. Approach to the Management of Recently Diagnosed Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: A User’s Guide for Adult and Pediatric Gastroenterologists. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:47–65.

Singh S, Qian AS, Nguyen NH, Ho SKM, Luo J, Jairath V, et al. Trends in U. S. Health Care Spending on Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 1996–2016. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;28:364–72.

Scott FI, Lichtenstein GR. Approach to the Patient with Mild Crohn’s Disease: a 2016 Update. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2016;18:50.

Gomollón F, Dignass A, Annese V, Tilg H, Van Assche G, Lindsay JO, et al. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease 2016: Part 1: Diagnosis and Medical Management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:3–25.

Feuerstein JD, Ho EY, Shmidt E, Singh H, Falck-Ytter Y, Sultan S, et al. AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Medical Management of Moderate to Severe Luminal and Perianal Fistulizing Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology Elsevier. 2021;160:2496–508.

Colombel J-F, Panaccione R, Bossuyt P, Lukas M, Baert F, Vaňásek T, et al. Effect of tight control management on Crohn’s disease (CALM): a multicentre, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2017;390:2779–89.

Reenaers C, Pirard C, Vankemseke C, Latour P, Belaiche J, Louis E. Long-term evolution and predictive factors of mild inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Taylor & Francis. 2016;51:712–9.

Zabana Y, Garcia-Planella E, van Domselaar M, Mañosa M, Gordillo J, López-Sanromán A, et al. Predictors of favourable outcome in inflammatory Crohn’s disease A retrospective observational study. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;36:616–23.

Cosnes J, Bourrier A, Nion-Larmurier I, Sokol H, Beaugerie L, Seksik P. Factors affecting outcomes in Crohn’s disease over 15 years. Gut BMJ Publishing Group. 2012;61:1140–5.

Munkholm P, Langholz E, Davidsen M, Binder V. Disease Activity Courses in a Regional Cohort of Crohn’s Disease Patients. Scand J Gastroenterol Taylor & Francis. 1995;30:699–706.

Agrawal M, Miranda MB, Walsh S, Narula N, Colombel J-F, Ungaro RC. Prevalence and Progression of Incidental Terminal Ileitis on Non-diagnostic Colonoscopy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:1455–63.

Tinè F, Rossi F, Sferrazza A, Orlando A, Mocciaro F, Scimeca D, et al. Meta-analysis: remission and response from control arms of randomized trials of biological therapies for active luminal Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:1210–23.

Faubion WA, Loftus EV, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. The natural history of corticosteroid therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:255–60.

Ho G-T, Chiam P, Drummond H, Loane J, Arnott IDR, Satsangi J. The efficacy of corticosteroid therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: analysis of a 5-year UK inception cohort. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:319–30.

•• Torres J, Bonovas S, Doherty G, Kucharzik T, Gisbert JP, Raine T, et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn’s Disease: Medical Treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:4–22. The ECCO guidelines focus on features predicting a low 5-year risk of disease progression within their definition of mild disease. These guidelines include ileocolonic location and ever being treated with systemic steroids. No maintenance treatment is also endorsed as an option for some low-risk patients.

Greenberg GR, Feagan BG, Martin F, Sutherland LR, Thomson AB, Williams CN, et al. Oral budesonide for active Crohn’s disease. Canadian Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:836–41.

Tremaine WJ, Hanauer SB, Katz S, Winston BD, Levine JG, Persson T, et al. Budesonide CIR capsules (once or twice daily divided-dose) in active Crohn’s disease: a randomized placebo-controlled study in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1748–54.

Suzuki Y, Motoya S, Takazoe M, Kosaka T, Date M, Nii M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of oral budesonide in Japanese patients with active Crohn’s disease: a multicentre, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group Phase II study. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:239–47.

Rezaie A, Kuenzig ME, Benchimol EI, Griffiths AM, Otley AR, Steinhart AH, et al. Budesonide for induction of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;CD000296.

Burisch J, Bergemalm D, Halfvarson J, Domislovic V, Krznaric Z, Goldis A, et al. The use of 5-aminosalicylate for patients with Crohn’s disease in a prospective European inception cohort with 5 years follow-up - an Epi-IBD study. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2020;8:949–60.

Lim W-C, Wang Y, MacDonald JK, Hanauer S. Aminosalicylates for induction of remission or response in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;7:CD008870.

Tromm A, Bunganič I, Tomsová E, Tulassay Z, Lukáš M, Kykal J, et al. Budesonide 9 mg is at least as effective as mesalamine 4.5 g in patients with mildly to moderately active Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:425-434.e1. quiz e13-14.

Thomsen OO, Cortot A, Jewell D, Wright JP, Winter T, Veloso FT, et al. A comparison of budesonide and mesalamine for active Crohn’s disease. International Budesonide-Mesalamine Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:370–4.

Goldman P. Therapeutic Implications of the Intestinal Microflora. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:623–8.

Feagan BG, Rochon J, Fedorak RN, Irvine EJ, Wild G, Sutherland L, et al. Methotrexate for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. The North American Crohn’s Study Group Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:292–7.

Chande N, Patton PH, Tsoulis DJ, Thomas BS, MacDonald JK. Azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;CD000067.

Mantzaris GJ, Christidou A, Sfakianakis M, Roussos A, Koilakou S, Petraki K, et al. Azathioprine is superior to budesonide in achieving and maintaining mucosal healing and histologic remission in steroid-dependent Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:375–82.

Lemaitre M, Kirchgesner J, Rudnichi A, Carrat F, Zureik M, Carbonnel F, et al. Association Between Use of Thiopurines or Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonists Alone or in Combination and Risk of Lymphoma in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. JAMA. 2017;318:1679–86.

Sokol H, Landman C, Seksik P, Berard L, Montil M, Nion-Larmurier I, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation to maintain remission in Crohn’s disease: a pilot randomized controlled study. Microbiome. 2020;8:12.

Gutin L, Piceno Y, Fadrosh D, Lynch K, Zydek M, Kassam Z, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant for Crohn disease: A study evaluating safety, efficacy, and microbiome profile. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:807–14.

Limketkai BN, Akobeng AK, Gordon M, Adepoju AA. Probiotics for induction of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;7:CD006634.

Rhodes JM, Subramanian S, Flanagan PK, Horgan GW, Martin K, Mansfield J, et al. Randomized Trial of Ciprofloxacin Doxycycline and Hydroxychloroquine Versus Budesonide in Active Crohn’s Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:2700–11.

Townsend CM, Parker CE, MacDonald JK, Nguyen TM, Jairath V, Feagan BG, et al. Antibiotics for induction and maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;2:CD012730.

Prantera C, Lochs H, Grimaldi M, Danese S, Scribano ML, Gionchetti P, et al. Rifaximin-extended intestinal release induces remission in patients with moderately active Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:473-481.e4.

Parker CE, Nguyen TM, Segal D, MacDonald JK, Chande N. Low dose naltrexone for induction of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;2018:CD010410.

Naftali T, Bar-Lev Schleider L, Almog S, Meiri D, Konikoff FM. Oral CBD-rich Cannabis Induces Clinical but Not Endoscopic Response in Patients with Crohn’s Disease, a Randomised Controlled Trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:1799–806.

Heuschkel RB, Menache CC, Megerian JT, Baird AE. Enteral nutrition and corticosteroids in the treatment of acute Crohn’s disease in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000;31:8–15.

Sigall Boneh R, Van Limbergen J, Wine E, Assa A, Shaoul R, Milman P, et al. Dietary Therapies Induce Rapid Response and Remission in Pediatric Patients With Active Crohn’s Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2021;19:752–9.

Levine A, Wine E, Assa A, Sigall Boneh R, Shaoul R, Kori M, et al. Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diet Plus Partial Enteral Nutrition Induces Sustained Remission in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:440-450.e8.

• Yanai H, Levine A, Hirsch A, Boneh RS, Kopylov U, Eran HB, et al. The Crohn’s disease exclusion diet for induction and maintenance of remission in adults with mild-to-moderate Crohn’s disease (CDED-AD): an open-label, pilot, randomised trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol Elsevier. 2022;7:49–59. Enteral nutrition has been widely recommended as an induction and maintenance strategy for pediatric patients, but issues with interest and long-term adherence have limited implementation in adults. However, for motivated patients, the CDED may represent an effective option with a favorable safety profile. Further real-life implementation studies are needed.

Lewis JD, Sandler RS, Brotherton C, Brensinger C, Li H, Kappelman MD, et al. A Randomized Trial Comparing the Specific Carbohydrate Diet to a Mediterranean Diet in Adults With Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:837-852.e9.

Olendzki BC, Silverstein TD, Persuitte GM, Ma Y, Baldwin KR, Cave D. An anti-inflammatory diet as treatment for inflammatory bowel disease: a case series report. Nutr J. 2014;13:5.

Langhorst J, Wulfert H, Lauche R, Klose P, Cramer H, Dobos GJ, et al. Systematic review of complementary and alternative medicine treatments in inflammatory bowel diseases. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:86–106.

Omer B, Krebs S, Omer H, Noor TO. Steroid-sparing effect of wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) in Crohn’s disease: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Phytomedicine Int J Phytother Phytopharm. 2007;14:87–95.

Krebs S, Omer TN, Omer B. Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) suppresses tumour necrosis factor alpha and accelerates healing in patients with Crohn’s disease - A controlled clinical trial. Phytomedicine Int J Phytother Phytopharm. 2010;17:305–9.

Hanai H, Iida T, Takeuchi K, Watanabe F, Maruyama Y, Andoh A, et al. Curcumin maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis: randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2006;4:1502–6.

Sugimoto K, Ikeya K, Bamba S, Andoh A, Yamasaki H, Mitsuyama K, et al. Highly Bioavailable Curcumin Derivative Ameliorates Crohn’s Disease Symptoms: A Randomized, Double-Blind. Multicenter Study J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:1693–701.

Horta D, Lira A, Sanchez-Lloansi M, Villoria A, Teggiachi M, García-Rojo D, et al. A Prospective Pilot Randomized Study: Electroacupuncture vs. Sham Procedure for the Treatment of Fatigue in Patients With Quiescent Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:484–92.

Joos S, Brinkhaus B, Maluche C, Maupai N, Kohnen R, Kraehmer N, et al. Acupuncture and moxibustion in the treatment of active Crohn’s disease: a randomized controlled study. Digestion. 2004;69:131–9.

Bao C-H, Zhao J-M, Liu H-R, Lu Y, Zhu Y-F, Shi Y, et al. Randomized controlled trial: Moxibustion and acupuncture for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol WJG. 2014;20:11000–11.

Bao C, Wu L, Wang D, Chen L, Jin X, Shi Y, et al. Acupuncture improves the symptoms, intestinal microbiota, and inflammation of patients with mild to moderate Crohn’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;45: 101300.

Hua X, Ungaro RC, Petrick LM, Chan AT, Porter CK, Khalili H, et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease is Associated with Prediagnostic Perturbances in Metabolic Pathways. Gastroenterology. 2022;S0016–5085(22):01061–7.

Funding

MA is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K23DK129762-01). RCU is supported by an NIH K23KD111995-01A1 Career Development Award.

AA is supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R21 DK127227, R01-DK127171), the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, and the Chleck Family Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The corresponding author confirms on behalf of all authors that there have been no involvements that might raise the question of bias in the work reported or in the conclusions, implications, or opinions stated.

JDC reports no conflict of interest.

PK reports no conflict of interest.

AA has served on scientific advisory boards for Abbvie, Takeda, Gilead, and Merck and has received research support from Pfizer.

JFC reports receiving research grants from AbbVie, Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Takeda; receiving payment for lectures from AbbVie, Amgen, Allergan, Inc. Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Shire, and Takeda; receiving consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene Corporation, Eli Lilly, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Galmed Research, Glaxo Smith Kline, Geneva, Iterative Scopes, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kaleido Biosciences, Landos, Otsuka, Pfizer, Prometheus, Sanofi, Takeda, TiGenix,; and hold stock options in Intestinal Biotech Development.

MA reports no conflict of interest.

RCU has served as an advisory board member or consultant for AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Pfizer, and Takeda; research support from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and Pfizer.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Claytor, J., Kumar, P., Ananthakrishnan, A.N. et al. Mild Crohn’s Disease: Definition and Management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 25, 45–51 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-023-00863-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-023-00863-y