Abstract

Nicholas of Cusa’s deployment of an omnivoyant image in the De visione Dei has been said to deconstruct Leon Battista Alberti’s mathematical determination of space in single-point linear perspective. While there has been some debate over whether the omnivoyant functions like a medieval icon or instead like a Renaissance painting, what has been neglected is a more careful analysis of what underlies the very structure of omnivoyance, namely the milieu from which its contradictions and paradoxes emerge. In this article, I will show how thinking the milieu of vision, implicit in Cusa’s optics, lets us overcome any overly simple binaries in these debates and deepen our understanding of the meaning of omnivoyance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

To begin his De visione Dei, Nicholas of Cusa uses an experiment with an omnivoyant image to illustrate his understanding of the gaze of God. The omnivoyant image is a face painted in such a way that the eyes seem to follow the one who moves in front of it and looks back at it. Since the effect is the same for each who stands before it, when they communicate their experience to the others, they can only conclude that the gaze follows all of them at the same time. The economy of the exchange of gazes combined with its relation to language—listening to the voice of the other who also sees the gaze seeing her—has thus been seen to be more than an analogy to the gaze of God. The way in which space unfolds under these gazes has been understood as an alternative to Leon Battista Alberti’s mathematical determination of space constructed through single-point linear perspective in painting.

Though he never mentions Alberti in this treatise, Cusa’s De visione Dei (1453) was written in part as a critique of the new perspective first systematically outlined by Alberti in his De pictura (1435) (Belting 2011, p. 221). It is unclear whether Cusa met Alberti at the court of the Pope or among certain Florentine intellectual circles.Footnote 1 But the scholarly consensus is that they were acquainted. If Alberti is often seen as proto-modern in his objective account of space, Cusa’s alternative optics is not necessarily the antimodern position. In certain ways, his description of the relation between the viewer and the image is in continuity with medieval understandings of the icon. At the same time, his account offers something particularly modern, or, at least, not medieval.

The modernity of Cusa’s account is grounded first of all in the fact that the omnivoyant image is made by writing a modern perspectival technique over a traditional icon. While a certain type of intimate gaze is invented during the Renaissance through the use of perspective, the gaze applied to this icon is not only intimate but omnivoyant: the conjunction of the two together being a result of the perspectival technique. The gaze that sees each as if it were looking at no other (intimately), sees all at the same time. It sees particularity and totality at once. So, while Cusa’s image has something in common with the emerging modern world, in contrast to the modern, objective account of space, Cusa’s example of the omnivoyant image does not permit the one outside the image—the viewer—to be removed from the spatial field in which the image exists. Insofar as the viewer remains within the space of the icon, Cusa does not mark an absolute rupture with the phenomenology of the icon, even as the optics operates otherwise. In other words, he completely transfigures the iconic economy in light of Renaissance debates on perspective.

But if remaining in the same space is neither accomplished according to the old iconic economy nor according to the modern, mathematical one, we must explore in what way precisely the omnivoyant viewer and the ordinary viewer that looks back at it remain in the same space. Debates concerning the nature of the omnivoyant image—whether it functions as an icon or an image, for example—have obscured the way in which the omnivoyant resists functioning as a spectacle of any sort, or for that matter, as a spectator. While critiques of linear perspective criticize the illegitimacy of its substratum (a geometry of straight lines), the substratum of Cusa’s alternative optics has not been investigated thoroughly. I will argue that the omnivoyant primarily functions as the milieu in which all vision takes place and thus, insofar as seeing is being for Cusa, the milieu in which all being finds its ground.

The beginning of this article will enframe my analysis within Cusa’s historical situation with respect to Alberti, particularly examining the way Cusa deconstructs Alberti’s linear perspective through the experiment with the omnivoyant image. Subsequently, I will show how investigating more adequately the ground or milieu of Cusa’s theory of vision helps us to overcome a strict opposition between these positions (Alberti versus Cusa, icon versus image) without erasing the differences. This will be achieved by showing that what Cusa describes as the coincidence of seeing and being seen is a dynamic, maximal relation between the coinciding terms. It is through working out the logic of the milieu of vision—the background in which seeing and being seen takes place—that we can understand how omnivoyant and voyant, world and viewer are entangled in the same space, the same visibility which omnivoyance creates.

Seeing and Technique: Gazing into the Image

The relation of Cusa’s work to that of Alberti and to the emergence of optical geometry more broadly has been examined in a variety of texts. The central texts that I will engage here are Hans Belting’s Florence and Baghdad: Renaissance Art and Arab Science (2008, German edition); Karsten Harries’ Infinity and Perspective (2002); Johannes Hoff’s The Analogical Turn: Rethinking Modernity with Nicholas of Cusa (2013); and Charles Carman’s Leon Battista Alberti and Nicholas Cusanus: Towards an Epistemology of Vision for Italian Renaissance Art and Culture (2014). For those unfamiliar with these texts, I will summarize some of the arguments and give a brief account of what the new perspective was.

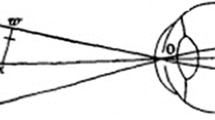

In De Pictura, Alberti writes, ‘The painter is concerned solely with representing what can be seen’ (p. 43). In order to represent what can be seen, Alberti investigates the power of sight and its perception of planes and lines, which allows the painter to make present what he can see through reproducing these lines and surfaces: ‘as soon as the observer changes his position these planes appear larger, of a different outline or of a different colour’ (p. 45). These visible qualities are ‘measured with sight,’ he writes, justifying this claim by invoking the geometry of light, particularly the understanding of the triangle of sight. The extreme rays refracting off the perceived object measure the quantity of the thing perceived and meet again in the eye, forming a triangle whose three points are the two opposite edges of the thing seen and the eye which perceives them. Alberti shows how we can put a screen in front of the gaze so that the visual rays, converging toward the eye land there in a mathematically measurable slice of real perception just in the same way that one can take any perpendicular slice through a cone and get a circle or oval. In order to see the painting correctly, the viewer must understand the painting as a screen or window in front of her gaze. Linear perspective uses a vanishing point in which all the lines of perspective converge in the painting. This vanishing point is the mirror image of the eye of the one who gazes. There is, as it were, a cone of perception spreading out from the eye of the viewer until it strikes the painting. The cone then re-converges as it goes ‘into’ the painting to meet again at the vanishing point in the way that parallel lines seem to meet at the horizon. This geometry of triangles or cones from the eye to the painting and the painting to the vanishing point fixes the way each object in the painting is constructed so that the further away is depicted as smaller as it reaches the tip of the cone while the nearer is larger, filling out the cone’s base.

If Alberti’s method seems to claim to depict reality as it is, that is, to provide a ‘realism,’ the method nevertheless has a genealogy as an artificial reconstruction of perception. Linear perspective developed from the optical discoveries of the Islamic scientist and philosopher Alhasen, and Biagio da Parma’s subsequent mathematical account of visual space that ‘westernized’ it by uniting the optical geometry with the space of images. Belting shows that the optics developed by Alhasen—and that were made possible by the Islamic distrust of images and consequent geometric account of perception—were, in the iconophilic West, converted into a theory of pictures, a way of mathematically determining the image which appears ‘on’ the geometrical substratum as it were. In the Islamic world, the geometry of light actually coincides with the art. (For Muslims, mathematics itself is sacred.) In the West, however, where pictures are what revealed the divine, the mathematics became a background on which pictures could be revealed. Alhasen would not have considered it possible to represent the world in images precisely because perception of the world requires two ways of perceiving: an exterior, physical vision—the perception of refracted light (geometrical perception of objects)—and the interior vision which is judgment and imagination that gives meaning to what we see (Belting 2011, pp. 107–108). If for Islamic thinkers like Alhasen, imagination was necessarily an interior action and therefore could not be represented in art (an exterior medium), the Western invention of perspective would fuse Alhasen’s understanding of visual rays with the imagination by placing the two on a flat surface ‘in front of the eyes and not within the eye’ (Belting, p. 111). The invention of perspective then relies upon a conflation of the interior and exterior produced by the externalization of conceptualization and imagination—the concept or eidos as a projected transcendence.

Biagio da Parma aimed to reconstruct the gaze according to the rules of proportionality, which is a way of reducing vision to a comparative mode.Footnote 2 In light of late medieval debates about nominalism and perspectivism, the precision of scientific measurement was seen to be the only thing that could overcome the uncertainty of ordinary perception, which could always be deceptive. The ultimate goal in developing a mathematical account of visual space was to achieve epistemological certainty. A precise methodology sought to control perception and thereby bring it in line with what could be known with certitude. Only a mathematical model could provide this absolute certainty. Since it was images and bodies that in the West manifested truth, the certainty of mathematics would need to be applied to control these images and bodies. Uniting image and mathematics, perspective creates an artificial construct of space that stands between the viewer and the thing seen, a mathematical substrate where the seen can be converted into an object like a painting—three-dimensional space re-presented on a flat surface. Only when space is redefined as visual space is it ‘possible to determine the location of the visual rays and visual forms’ (Belting 2011, p. 147). This modified experience of space as a system of coordinates that converge in the eye has been read as the forerunner of Descartes’ perspectiva artificialis (Moulin 2017, p. 34 n4).

This redefinition exteriorizes space. The gaze becomes the a priori condition of a spatial system and is not itself part of this system. The perceiver is no longer tangled in the perceived. The eye operates as a fixed point from which to perceive things in space. Space is ‘extended,’ fixed by an a priori mathematical system. We cannot say in this case that space is ‘extending,’ which would leave it indeterminate. It is because space is measured by the eye, a single-fixed gaze that methodological certainty converges upon the ego. In order to achieve epistemic certainty by proportional measure, that which appears must be controlled by someone doing the measuring. As Johannes Hoff puts it: ‘It is easier to achieve epistemic certainty about what we have created with our own mind than about entities of indeterminate origin’ (p. 45). What is determined by the fixed gaze is necessarily certain because its being coincides with the act of measuring it.

Critics of the worldview underlying linear perspective have several characteristic arguments. First, even though in a certain sense this perspectival technique seems to allow us to create more realistic images, it is not primarily a form of realism. It does not conform to how we really see, but is a scientific technique to control reality. The eye must be trained to see in a way that is peculiarly unnatural to it (Florensky 2002, p. 225). In fact, this artificial construction was not initially favored because of its realism, but because it was a means of control—a way to produce and reproduce images that are ‘like’ the images we see in real life, but do not participate in that reality. Like other technologies, linear perspective won out not because it was a true representation of reality but because it worked. It reproduced itself consistently and methodically.Footnote 3 Second, linear perspective is illusionistic. It is a view from a single eye and does not take into account the fact that we synthesize our perspective from the view of two eyes. It is ‘monarchical,’ ‘dominant,’ and ‘monocular like the Cyclops’ (Florensky 2002 p. 262). Lastly, it depicts a dead reality, frozen outside of time in a separate world from the viewer (Florensky 2002, p. 263). These critiques, highlighted to one degree or another by Florensky, Hoff, Harries, and Belting, suggest that linear perspective was a forerunner of the controlling gaze of the Age of Enlightenment.

By contrast, Charles Carman has minimized the importance of the mathematics and the geometry for Alberti. He suggests instead that the vanishing point is not primarily a means of mathematical control, but has a symbolic meaning. Carman takes issue with the tradition that began with Santinelli of reading Alberti as a rationalistic thinker merely obedient to ‘the rigid laws of optics and geometry’ in contrast to Cusa where ‘all can move freely’ in front of the icon.Footnote 4 The view that linear perspective requires one to stand in exactly one position to see the painting correctly is, for Carman, simply false.Footnote 5 As a humanist, Alberti thought with symbols and metaphors, more than calculations or concepts (Carman 2014, p. 12). Carman points out that, while the cone of perception from the eye to the painting is finite, its image within the painting toward the vanishing point is thought by Alberti to be an infinite cone, ‘a visual pyramid that extends to infinity,’ as Carman paraphrases, though quickly qualifying it with Alberti’s own words ‘quasi per sino in infinito’: a cone that extends ‘almost to infinity.’Footnote 6 The perspectival technique, in other words, is not primarily a means of control, but is a symbolic representation of transcendence. Thus, Carman will argue for a parallel between Cusa’s concept of the omnivoyant, infinite gaze and the vanishing point of linear perspective (p. 90ff). The others that I have cited by contrast use Cusa as a foil to Alberti’s science: Cusa, a thinker who holds on to the sacramental ontology of the middle ages (Hoff), and who surpasses Copernicus pre-emptively with a ‘radical perspectivism’ (Harries). Even if I do not entirely agree with Carman’s revisionary attempt to unite Cusa and Alberti, nevertheless, his arguments contain some penetrating insights that we will need to evaluate after we have examined Cusa’s understanding of the omnivoyant. For now, we can take both a metaphoric, symbolical representation and mathematical measurement to constitute the fundamental substrate upon which images appear in the Albertian model.

Deconstructing and Reconstructing the Perspectival Gaze: Gazing out of the Image

Even those who agree with Carman’s thesis could not deny that, at least to some degree, the new perspective had as its goal a certain control over the painted surface. One could use the technique rather than one’s own eye to make a painting. This perspectival rule is no doubt only slavishly followed by third-tier artists, as Florensky long ago noted (1919). Nevertheless, it is the rule. Cusa’s experiment with the icon could not be further from an understanding of perspective as a means of control over the reproduction of reality. Cusa uses the omnivoyant face—a face that appears to be looking at you wherever you stand with respect to it—to deconstruct the single-point view that creates the viewers autonomy and mastery over the painting.

De visione Dei is part of a dialog he is maintaining with the monks of Tegernsee. He sends one of these omnivoyant images to the monks with the preface of this text asking them to perform the following experiment. First, he asks them to stand before the image. As they walk back and forth in front of it, he asks that they note how the gaze follows them wherever they go. Then, he asks two of them to do this at the same time, walking in different directions. While a monk will always know immediately that the gaze follows him, he cannot know through direct experience that it follows his brother monk as well. So he must ask the other what he sees to discover that the gaze follows him too and at the same time. The knowledge of the astonishing plurality of the gaze is not derived from immediate experience but from the verbal testimony of the other. Cusa writes, ‘You will marvel at how it is possible that the face looks at all and each (omnes et singulos) at the same time. For the imagination of the one who is standing in the east cannot conceive that the icon’s gaze is turned in any other direction ...’ If he did not hear the other tell him that the gaze follows him too, he would not believe that it was possible (DVD, praef. (3)).Footnote 7 Now, this simultaneity of multiple objects of the gaze is not possible within the three-dimensional extended space that rules in perspective—the three-dimensionality that extends from the eye and makes distinctions by calculating difference of location with respect to itself, the eye that sees and by seeing measures distance and establishes difference. According to a gaze that is measuring distances between objects in perspective, each point is quantifiably different. The omnivoyant gaze, by contrast, regards all and each at the same time, that is to say, it disregards quantifiable space.

Cusa’s experiment with the monks is a scientific experiment to deconstruct the positivism of scientific objectivity. Geometrical determination is deconstructed precisely by means of an excess over the ‘gaze’ as such. This excess is expressed by showing that, while a gaze that moves in multiple directions at the same time is impossible within geometric space, such a gaze appears within the space governed by the omnivoyant. It is only the use of language with respect to this space that allows us to realize how this space contradicts a geometrical concept of space, for language is what allows us to see from the perspective of another, which is already to be at two places at once if not quantifiably, then qualitatively. Language opens to qualitative spatial dimensions. This contradiction of three-dimensional space combined with the use of language that realizes this contradiction makes Cusa’s idea of space dynamic, first of all in a continuous motion from the quantitative to the qualitative which grounds the quantitative.Footnote 8

The essential difference between Alberti and Cusa can be summed up in this way. Alberti’s method is based on a comparative analysis and thereby excludes the superlative starting point of Cusa’s optics. Alberti justifies his approach saying that ‘comparison contains within itself a power which immediately demonstrates in objects which is more, less or equal’ (Alberti 1950, p. 54). It is the gaze that measures these magnitudes: ‘Perhaps Protagoras, by saying that man is the mode and measure of all things, meant that all the accidents of things are known through comparison to the accidents of man’ (Alberti 1950, p. 54). The comparative method includes the quantitative, which is a means of comparison, but it also includes the idea of a humanist metaphorical representation as discussed above. Both metaphor and perspectival technique are accomplished by measuring one thing next to another.

Cusa’s metaphysics is not anti-perspectival nor anti-comparative. It is radically perspectival. It is radically perspectival because it is superlative. Rather than offering a critique of perspective as such, it surpasses perspective by rendering comparative logics moot in the face of a maximal or superlative logic. For Cusa, the relation between the divine and the world is not that between the infinite and the finite but between the absolute infinite and the contracted infinite. The omnivoyant gaze, however, admits no comparison for at least two reasons. First, from the side of the one who looks upon the omnivoyant: there is no place from which to measure it against anything else since each omnivoyant gaze would encompass every visible. There are then no spatial coordinates in which to determine it or which mark its determination of space. The omnivoyant renders space as coordinate system unintelligible, or at least immeasurable, since anywhere that I am, when I look upon the omnivoyant, I see the same thing. Second, from the side of the omnivoyant: the omnivoyant likewise cannot compare the gazes which gaze back at it, since, by means of comparison, they are all interchangeable. Difference is not seen by measuring one next to the other, but by seeing each as a singularity. Outside of any comparison, the only way to access this exchange of gazes is through the coincidence of opposites where to see is to be seen, to both give and receive oneself as a singularity. The one seen is a singularity not because it possesses individuality as a property, but ‘because it owes everything’ to the one who by seeing it creates it.Footnote 9 Not a comparative, measurable relation between gazes, but a superlative or maximal one that permits this paradoxical coincidence of seeing and being seen and a coincidence of total reception of the self from another with the absolute singularity of the self. To perceive the omnivoyant gaze, no change of location is necessary, only a conversion in the way of seeing: from a comparative mode to a mode that is superlative.

While in Alberti the imagination is exteriorized so that it can be determined by the geometry of vision on the plane of the painting, Cusa’s omnivoyant creates a space outside of itself, not on its own plane, but among those who stand in front of it.Footnote 10 The human gaze, looking into the image, cannot conceive how the image proliferates its gaze in non-represented space, multiplying in such a way that the gaze follows me and my brother monks at the same time (DVD, praef. (3)). In Cusa’s experiment, exterior seeing connects with an interior vision linked to language: believing the visually impossible through using the word as a form of seeing that surpasses the vision of the eye. I must hear my brother tell me that the gaze follows him too in order to know that it is possible. (DVD, praef. (3)). Speech leads the singular to the all: that the gaze does not only regard me particularly (‘as if it had concern for no other’), but regards all even while it continues to regard each in its specificity (DVD, praef. (4)). Still, we can never form a comprehensible concept or image of this omnivoyance since it is impossible to experience the proliferation of the gaze directly. Each person has only one perspective. Omnivoyance is by definition an incomprehensible concept and must be grasped incomprehensibly (DI, I, 4 (12)), leading from experience into language and from language back into a broadened experience.

The intimacy of the gaze is not Cusa’s invention. Nor is the gaze that sees all. The Byzantine Pantocrator has a gaze that follows the viewer, but the gaze is stylized and impersonal. What is new at the time of Cusa is a technique that allows the all-seeing gaze to be an intimate gaze. As Clifton Olds points out, the intimacy of the gaze developed with the development of perspective. Olds uses the example of Giotto’s Judas and Christ to illustrate the new emphasis on the intimate ‘power of the gaze’ and a ‘growing psychological realism’: the intimate interaction of characters within the painting (Olds 1996, p. 255). While perspective creates this intimacy between characters within the painting, it can also create this intimacy between the painted character and the viewer. When the gaze of the painted figures crosses the plane of the painting perpendicularly, the gaze will always have the effect of following each viewer with an intimate gaze, which is why Cusa is able to list numerous examples of the omnivoyant image. But unlike the stare of a Byzantine Pantocrator, the use of perspective adds intimacy to the all-seeing gaze. It sees ‘each’ singularly or lovingly, as if it is looking into the soul. Olds thus remarks that it is ‘ironic and paradoxical’ that Cusa’s use of the icon contradicts perspective since perspective is what makes possible the intimate gaze (p. 256). It is because of this development that there is some debate about whether the omnivoyant indeed should be understood as an icon at all.

Jean-Luc Marion and Emmanuel Falque, for example, offer opposing readings of the meaning of the ‘icona dei.’ While Marion argues that it should indeed be translated into French as icône, following Hervé Pasqua’s translation, Falque follows Agnès Minazzoli in translating it ‘tableau’: as ‘painting’ or ‘image’ rather than as icon. Falque argues that the image that Nicholas uses in his experiment with the monks is not a religious icon and is not placed within a religious or liturgical context: it is simply hung on the wall in the refectory: ‘Thus to contemplate the figure is not to pray to it nor to venerate it. It opens only, but certainly, to an “experimental process” into which the whole community of monks is invited’ (Falque 2014, p. 48). The Renaissance circles with which Cusa associated were more open to ‘experiment’ and ‘paintings’ than to icons in the traditional sense. As we have already discussed, the technique that produced the intimate all-seeing gaze was something new that did not exist in traditional iconography.

With regard to images painted with this technique that creates the appearance of omnivoyance, Cusa references several examples including a work by Rogier van der Weyden (which he calls a tabula even though it is a mural) and the “Veronica” in his own chapel (DVD, pr. (2)). The Veronica, or vera icona (true icon), was a replication of the image of Christ that was said to be imprinted on the veil on which he dried his face on his way to Calvary.Footnote 11 Yet, while Cusa references secular examples of this technique, it seems highly likely that the one he sends to the monks is a traditional icon with this non-iconographic technique written over it giving the Christ an all-seeing intimate gaze, for he explicitly calls it ‘an icon of God’ (quam eiconam dei apello) (DVD, praef. (2)). In his article, Marion is quite dismissive even of the possibility of translating icona as ‘tableau’ (Marion 2016, p. 15). Nevertheless, the selection of examples and its placement within an experimental setting makes the status of the icona dei more ambiguous than this explicit reference to the icon would allow.

The omnivoyant’s ‘counter-gaze’ out of the painting is not the direct inverse of the gaze into the painting. It does not accomplish the same thing, inversely, as linear perspective’s gaze into the painting. One reason is that the monks are not fixed in a single position by the gaze of the icon, as the perspective painting is fixed by the gaze of the painter. The monks can do as they please and still be regarded in the same way. They move freely back and forth and still see the same thing. There are in fact no positions in front of the gaze, for there is no measureable space within this economy.

A second reason is that the omnivoyant functions not like a window, as in Alberti’s model, but like a mirror. The face that is turned toward me, wherever I am, will conform to the one who sees it, and does not impose itself like the Levinasian Other (if we are to allude to phenomenological conversation from which Marion and Falque write). Cusa writes, ‘whoever looks on you with a loving face will find only your face looking on oneself with love. Whoever looks on you with anger will likewise find your face angry … if a lion were to attribute a face to you, it would judge it only as a lion’s face, if an ox, an ox’s, if an eagle an eagle’s’ (DVD, 6, (19)). While linear perspective posits the surface of the painting as a window on reality, the omnivoyant image is a mirror that blocks vision ‘into’ the painting by sending the gaze back out first of all to the one who views it, and then, through language, among the community that places itself in front of the omnivoyant. ‘Now I contemplate in a mirror, in an icon, in an enigma’ (in speculo, in eicona, in aenigmatum) (DVD, 4, (12)). Like a mirror, the plane of Cusa’s image spreads out into space as the smallest of mirrors can reflect a whole mountainFootnote 12 while the plane of Alberti’s painting narrows in two directions: into the vanishing point in the painting (the window) and into the singular gaze that looks at it. The mirror of the omnivoyant gaze thus captures the whole community, uniting them in its space. It is because of the mirroring effect that it becomes difficult to argue that the omnivoyant functions either as an icon (that transpierces the visible with the invisible) or as a Renaissance image that functions like a window.

This section has highlighted several aspects of omnivoyance that will need further development: a maximal rather than a comparative gaze; the creation of space by the omnivoyant among the community rather than the creation of space by the artist-technician on the plane of the painting; and the omnivoyant as mirror rather than the painting as window. These themes all point to how Cusa uses perspective in order to nullify it. He nullifies perspective not by negating its existence, but by taking it to the maximum, submitting it to his logic of the superlative.

Radical Perspective

If the new perspectivism allowed the world to be submitted to exact measurements, Cusa already saw that the certainty of these measurements were not universally certain but created their own universality: they were only certain from one particular perspective and were not measurable absolutely. Yet, Cusa suggests that the solution to the absolutizing of the discursive plane of the painting cannot be found in a reversion to a pre-perspectival existence. Rather, we must take perspective to its extreme. Cusa’s superlative logic does not imply perspective’s end, but rather perspective’s radicalization.

The monks in Cusa’s experiment do not have an omnivoyant gaze but they can conceive that the other has a perspective other than their own. Karsten Harries argues that Cusa’s concept of learned ignorance is itself ‘the principle of perspective’: ‘to think a perspective as a perspective is to be in some sense already beyond it, is to have become learned about its limitations’ (Harries 2001, p. 42). To see one’s own position as merely a perspective among many is to surpass one’s perspectival limitation. It is to see one’s own perspective from beyond itself. By imagining other point of views, you begin to make other point of views possible. The human limit (the binding of the gaze to a point of view) we might say is actually a possibility of infinite expansion toward other points of view that would not be possible without this limit. We could not acquire ‘other points of view’ if we did not start from a point of view, that is, from a perspective. Without a perspective, no point of view is possible; therefore, without a perspective, it is not possible to surpass one’s own perspective toward other viewpoints. Perspective, in other words, at once distorts reality (that is to say it is subjective and limited) and, at the same time, perspective is fertile: able to expand reality (toward hypothetical perspectives, for instance). This surpassing of perspective is what I will call radical perspective, following Harries. It is not achieved by objectifying reality from a particular viewpoint, but rather takes perspective to its extreme: seeing everything as perspectival. What I mean by ‘surpassing perspective’ does not mean re-inscribing the world in a new objectivism nor does radical perspective include a facile subjectivism.

To the contrary, radical perspective allows us to show that the mirroring effect of the omnivoyant is not a solipsistic economy. For Cusa, the mirroring effect of our vision of God does not mean that our perspectival vision is limited to a mere subjectivism by which we can only see ourselves and thus remains trapped in a projected world. The ‘living mirror of eternity’ does not conform to us. Rather, we are revealed in it:

Anyone who looks into this mirror sees one’s own form in the form of forms, which is the mirror. And one judges the form which one sees in the mirror to be the image of one’s own form since this is the case with a polished material mirror. Yet the contrary is true. For that which one sees in the mirror of eternity is not an image but what one sees is the truth of which the one who sees is an image. (DVD, 15 (63))

One does not see one’s own image instead of God, but the truth of oneself in God. Intellectually, we begin to participate in the truth of ourselves mirrored back to us by practicing radical perspectivism. It is because we can learn that the omnivoyant is the exemplar of all and of each as if of no other that we can ‘leap beyond the forms of all formable faces and beyond all figures’ (DVD, 6, (21)) to the form of forms in which is our true form. We can see God not only in our own face but in the face of others: ‘In all faces, the face of faces is seen veiled and in an enigma’ (DVD, 6, (21)). In a certain way, we can only begin to discover our true form by beginning to see from other perspectives. It is only in recognizing the reality of other perspectives that we recognize the mirror as omnivoyant, and thus as the form of forms which is itself formless. The leaping-beyond all formable faces takes place first through the possibility of inhabiting other perspectives hitherto unimaginable, even hitherto impossible. I will develop this point later.

In De docta ignorantia, Cusa develops his concept of space through his use of the trope of the ‘circle whose center is everywhere and circumference nowhere’ (DI, II, 11 (156)), which is analogous to the omnivoyant gaze of De visione Dei. While he indeed uses this trope to define God (the traditional use of this image), the more interesting move is when it becomes for him a definition for the universe itself (Harries 1975). It is fairly remarkable that before Copernicus is even living, Cusa already applies a certain homogeneity to space, at least insofar as concerns the medieval heterogeneity of the spheres. For instance, he speculates about the perspective of a person standing on the North star to argue that any place in the universe can seem like an unmoved center if that is the perspective from which one measures all movement (DI, II, 12 (162), 117). From the view of a person standing on the moon, the earth moves around the moon. I am standing still on the earth with respect to the ground under me, but with respect to someone standing on the sun, I am hurtling through space at 67,000 mph. These observations are now rather banal to us, but they were impossible speculations in the medieval cosmology in which the space of each sphere (the earth, the moon, the Sun, etc.) was heterogeneous to the others and which depended on the idea of an unmoved mover as absolute limit, an idea incompatible with Cusa’s view that stability itself is only relative to motion. One could not say that things operated the same way in the sublunar world as they did in the unchanging heavens.

But while Cusa already surpassed the medieval understanding of space, he did not give geometrical calculations an absolute status, as would the scientists of the Renaissance and modern period. Seeing that the sun only appears to move around the earth from the perspective of the earth did not lead Cusa to think that geometrical calculations would provide a non-perspectival, absolute truth. For Cusa, things move or have stability only from one point of view or another, not absolutely. One can still make accurate calculations as if the planets revolved around the earth, they are simply more complex calculations. It is more elegant to describe them as revolving around the sun. Further, Cusa would resist the developing modern concept of geometric space insofar as he refused ‘the assumption that every deviation in mathematical space can be disregarded as a quantité négligeable if it is not capable of being reduced to straight lines’ (Hoff 2013, p. 65). For Cusa, the world we live in is curved, never meeting up with the perfectly straight line which is his symbol of the absolute.Footnote 13 The irreducibility of the curved world into straight (but finite) geometrical figures meant for Cusa an infinite complexity of space and place that could not be reduced into a homogeneous system.Footnote 14 It also meant that the ground could not be understood as something fixed and finite. It was inherently indefinite. If moving from one place to another does not constitute a meaningful movement through space (since from another point of view, it is not a movement at all), we are required to rethink the categories of spatial differentiation without the category of movement or even of difference of location. The basic point is this: if every position is unstable, a comparative method can never make true claims about the fundamental, about the base and about the ground of existence. What is required is a method that is able to speak (no doubt indirectly) about the maximal, which is without comparison.

Coincidence at the Maximum

We need to explore further the logic of the maximum, the infinite gaze that does not see movement and stasis as real categories. When a quality passes from simply ‘more’ (comparative) to the most (superlative) a quantitative difference no longer obtains. The difference becomes absolute at the same time that all the rules regulating the difference as difference fall apart. The maximum itself becomes the regulating principle. For example, it is not a logical fault to say that the highest that can be thought coincides with that which is higher than can be thought (Anselm). To reach the highest is not to exit from logic and rationality (which would be one interpretation of ‘higher than can be thought’), and yet, at ‘the highest,’ the highest becomes its own measure and the measure of all. Since it is the measurer and not the measured, strictly speaking, it cannot be thought, even though it undoubtedly gives an order and a grammar. It gives something to be thought by not being itself thinkable. It gives place insofar as it fixes everything else with respect to itself.

Likewise, its superlative logic does not just mean that omnivoyance is beyond all comparison. It also means that the omnivoyant in a certain way coincides with the contracted. The omnivoyant not only defines that which it sees as ‘the contracted,’ that is to say, it opens a grammar of contraction. The omnivoyant also sees omnes et singulos, that is, beyond quantity. It encompasses contracted space and is not itself part of it. The omnivoyant is thus the most fundamental thing about the contracted. The omnivoyant and the contracted are linked not by similarity but by a coincidence at the maximum so that the contracted can also be an infinity (the contracted maximum). From now on, what matters is not the difference of the finite from the infinite, but the absolute infinite from the contracted infinite. For this reason the superlative, that is, the maximum, must be a maximum, according to the logic of sensation rather than the logic of ideation, since there is no site from which to compare one idea or form to the other. The omnivoyant only emerges in the place of the one it sees and not in the same space. The omnivoyant transcends the contracted by being hyperbolically immanent. It does not transcend in the way that the real object transcends in realisms or that the concept or idea transcends in idealisms. Further, the hyperbolic grammar contrasts with the formal grammar of non-contradiction, which arises from quantitatively or categorically separate things, that is, from a comparative mode of relation.

Nicholas calls the painted face an image of infinity since it bears no relation of comparison or measure to what it sees: ‘its gaze is not limited to an object or a place and thus is infinite’ (DVD, 15 (61)). Infinity is neither greater nor less than nor equal to anything. Unlike the gaze in or on the perspective painting, the gaze of the omnivoyant does not measure what it sees. The omnivoyant gaze has no intentionality. It does not arrive from in front of the one it sees, but in a sense, it arrives from behind, or from below. The one who is seen by the divine gaze is the ‘living image of omnipotent power’ (virtutis omnipotentiae tuae vivam imaginem) (DVD, 4 (11)). This living image, which Cusa identifies as free will, is constituted by reflection: ‘all my striving (conatus) is turned toward you because all your striving is turned toward me, when I give all my attention to you and never avert my mind’s eye because you hold me in your constant vision’ (Ibid). The logic here is not that of similarity between one thing and another. It is a maximal relation in which the seen is constituted as a self-constituting infinity. The free will that constitutes the image is not the freedom to see or not to see, but the freedom to will to be what you are in and of yourself. Without willing to be, you cannot be maximally given by the divine gaze:

... you have placed within my freedom that I be my own if I am willing. Hence, unless I am my own, you are not mine, for you would constrain my freedom since you cannot be mine unless I also am mine .... This depends on me and not on you, O Lord, for you do not limit your maximum goodness but lavish it on all who are able to receive it. (DVD, 7 (25))

It is no doubt a paradox that the dependent term in a causal relation—the relation of the image to its prototype—could be a self-constituting term. But because the relation of image to prototype is no longer a relation in which one term can be compared to the other, but is instead a superlative relation, the paradox must be insisted upon. Maximal relation would by definition lead to the self-constitution of the (now maximally) dependent term, which is the image. If it did not lead to self-constitution, the maximum and relation would be incompatible, for the increase from the comparative to the maximum would dissolve relation into identity. Although he does not express it this way, if we are to follow the logic of Cusa’s understanding of the image, a maximum relation would not result in identity between the terms, but rather, in the image, a maximum relation would coincide with a minimum relation in the same way that a maximal line coincides with a minimum line (DI, I, 13–14 (35–39)). Now, a minimum relation is nothing less than radical freedom. This freedom goes so far as self-constitution, which is not, in the image, the power to create one’s own being out of nothing but is nevertheless a power to create as ‘the living image of omnipotent power.’

Maximum relation is dynamically expressed as the freedom of self-constitution in the relation of language to perspective as Cusa develops it in the experiment with the icon. As living image, the human being is united to the absolute infinite in the expression of her limit, which is a maximum, and so is also an infinity, but a contracted one. Since her very limit is a maximum, she is at once not lacking anything that she would need to be complete, yet she contains the capacity to be more than she is. The living image is able to be more, to be a surplus, particularly through the deployment of language by which it surpasses the limits of its own perspective without becoming something other than itself. From the very beginning, the living image possesses the whole of what is given by the prototype since the prototype gives itself infinitely, for, being infinite, it cannot be broken into parts. It must be entirely given or not given at all. Yet, the image can only receive the prototype in the highest possible way through its own capacity for language, both speaking and listening to the other. Through language, the image exceeds its own perspective and actually achieves, rather than merely receives, a maximal relation with the absolute infinite.

Virtuality and Contraction

Because possibility emerges with actuality and actuality with possibility, possibilities cannot be said to be actualized. For Cusa, possibilities do not sit in some hermetically sealed logical or noetic realm before actuality comes along to switch them on like one turns on a light bulb. Their very possibility is actual, not merely logical. This is to say that they arise as a power, or virtus. In the passages I will quote below, what is usually translated as ‘power’ is the Latin word virtus, the intrinsic potency or strength of a thing, as when one speaks of the virtue of an herb with healing properties or even of human virtues like courage, justice, and patience. The virtus is a power directed toward a certain end. I have sometimes modified the translation of virtus to ‘virtue’, left it untranslated, or left the translation unmodified as ‘power’ in order to draw attention to the richness of the term. Virtual possibility is what allows Cusa to think the ground of vision in its instability and its immovability, in its inactivity and its impossibility.

Since virtual possibilities are already actual, not just possible, potencies, Cusa needed a term other than actualization to talk about the appearance of beings. Instead of actualizing, Cusa will say that possibilities contract. We can begin to explore what contraction would mean if we first understand that the virtual (that which refers to the virtus), and not the actual, is the reality of the possible.Footnote 15 Virtuality is the matrix of the real, the form of forms. It is in this way intrinsically related to the mirroring effect of the omnivoyant, which, as we have seen, is also described as the ‘form of forms.’ Cusa explains that ‘this absolute and supereminent power (virtus) gives to each seminal power (virtus) that power in which it virtually enfolds a tree (complicat virtualiter), together with all the things that are required for a sensible tree and all that accompany the being of a tree’ (DVD, I, 7 (23)). Virtuality is possibility that is already real, thus coincident with its actuality, but in seminal form: ‘And thus I see this tree as a certain unfolding of seminal virtue (virtutis seminalis) and the seed as a certain unfolding of omnipotent virtue,’ (DVD, I, 7 (24)). Both the possibility and the actuality of the tree emerges from the virtue of the seed ‘so that nothing can be found in the tree that does not proceed from the seed’s virtue.’ (Ibid). In a certain way, seminal virtue is the truth of the tree of which the realized tree is only the image.

One way Cusa explains this relation of seminal virtue is through his use of infinite figures, like the infinite triangle (DI I, 14 (37–39)).Footnote 16 The infinite triangle is not infinitely large. Rather, he says that if the narrow angle of an isosceles triangle is extended to infinity, the triangle collapses into a straight line which is infinite. Its extension to infinity is not largeness since at the infinite difference by magnitude breaks down: the maximal line is the minimal line. The infinite line coincides with the infinite triangle. But a finite triangle can never become this infinite triangle so long as it remains a triangle in space (with three angles equaling 180°). Nevertheless, the contracted triangle has the seminal power to approach the infinite triangle which is its measure. The infinity of contraction is this infinite approach which lays no claim to the exactitude of identity, while the absolute infinite is the infinite triangle that is always behind any contracted triangle. The infinite triangle collapses into a straight line at the absolute infinite as there are not a multiplicity of forms but one sole form behind all contracted things. While Cusa uses mathematical figures to gain some grasp of the maximum, the maximum is not at all ‘like’ the quantitative. In the end ‘we must leap beyond simple likeness’ (DI, I, 14 (33)) and ‘ascend from a quantitative to a non-quantitative triangle’ (DI, I, 14 (38)). Not a number or a quantity, the maximum is more like a field, a milieu in which the quantitative exists, a field that is infinitely spread out and undefined, as a maximum line would coincide with a maximum space.

Since the seed embraces all that the tree becomes, it is the tree’s contracted maximum, the maximum contracted virtus of the tree. But the maximum does not embrace or encompass as a form encompasses, since form collapses at the maximum into the single maximum and the contracted virtus (the seed) coincides with the absolute virtus, the Word. In God, seminal power coincides with absolute power because there is no mediating exemplar between the virtus that contracts the tree and the divine power that is uncontracted and which is ‘the face or exemplar of every arboreal face and each tree’ (DVD, I, 7 (23)). In God, ‘the seed is the truth and exemplar of itself .... And that power of seed, which is contracted, is that of the natural power of a species, which is contracted to its species and dwells therein as a contracted principle’ (DVD, I, 7 (24)). The omnivoyant as the form of forms thus coincides with the virtual as the matrix of the real.

Contracted seminal possibility is always on the way, approaching the absolute infinite which is its ground. The absolute infinite is said to be ‘negative’ because, as absolute, it is all-inclusive, which means that it is not itself included in the all that it encompasses: infinitude by not being included in the all is the negative infinite (Brient 2002, p. 123). But as ‘outside’ and ‘negative,’ it has inherent positive dimensions. It is an intensive, qualitative presence, a plenitude and completeness that is outside quantity as what unfolds the quantitative, outside of perspective as the milieu of vision in which perspective is possible.

With respect to the seminal virtue, therefore, possibility cannot be said to actualize, but must be said to contract. There is no pre-existing form to actualize (no additional level of mediation), since actuality is also seminal and virtual. Contraction is the possibility of a thing in its auto-constitution from its own virtus. The virtus as its contracted infinity is the milieu in which the contracted touches the absolute. The omnivoyant is the seminal virtue of every perspectival gaze. It is the milieu of power by which contracted vision becomes possible in its unfolding beyond perspectival limitation. Virtuality, therefore, is the milieu of vision where one thing does not oppose another (movement-stasis, possibility-actuality), where nothing can be compared to the other, but which expresses a superlative union.

It is the concept of contraction that enables Cusa to develop a non-comparative method. Contraction lets him think the ground as neither pure possibility nor pure act, neither absolute movement nor absolute stasis. The ground is thought instead as coincidence of opposites: the coincidence of possibility-actuality and the coincidence of movement and stasis. With respect to radical perspective, contraction is needed to replace the distinction between the absolute and the moving. Since, according to Cusa’s principle of perspective, stasis is only relative to motion, stasis cannot represent the absolute. Rather than a relation of the absolute to the moving, radical perspective leads Cusa to conceive a relation of the absolute to the contracted. Thus, Cusa conceives of the universe as a contracted maximum of God’s absolute maximum, which is neither static nor moving, or both static and moving: moving with infinite speed, which is to say, perfectly still: ‘there is no simply maximum motion, since it coincides with rest.’Footnote 17 Non-contracted absolute vision is the ground of contracted vision, but both the absolute and the contracted manifest the coincidence. The contracted contains both movement and non-movement because the absolute contains both movement and non-movement. Human vision does not have the absolute capacity of God’s vision, but is limited in time and place. It is limited, first of all, as contracted and not as perspectival since to remain in perspective would be to see movement and stasis as decisive categories, and thus to take stasis as equivalent to the absolute, which is the sine qua non by which one is able to take one’s perspective as an unmoved center from which the movements of the world can be measured. Grounded in the idea of contraction, Cusa’s theory of vision does not pit dynamism against stasis, the uncertain flux against the fixity of mathematics. Radical perspectivism surpasses the perspectival categories that make movement the opposite of the absolute. It resituates the distinction as that between the absolute and the contracted. Absolute vision as the milieu in which contracted vision takes place does not imply or even allow for an absolute understood as fixity or stasis.

The Living Mirror of the Eye: the Concentrated Milieu

The ‘spread’ nature of a milieu is not a sufficient way to describe the ‘encompassing’ nature of omnivoyance. Nevertheless, the connection of milieu to sensation, atmosphere, environment, and place is critical. The encompassing nature of omnivoyance is concentrated in a gaze. Cusa’s cosmos is not, like Descartes’ world, infinite in extension, but is infinitely intense, infinite within itself because it is complete in itself. Infinite intensity signifies a qualitative infinite: the infinite richness of the world and of each particular thing (Brient 2002, p. 101). In other words, as Cusa describes it, the world is a contracted maximum. It cannot be greater than it is, yet more can be added. It cannot be greater because every possibility is already actualized (Dupré 1990, p. 155). This is to say nothing less than that it is a maximum. More can be added because every possibility increases with the increase of actuality. A maximum does not exhaust itself into pure act since the transfer of possibility into actuality remains in the realm of comparison and opposition (the non-maximal). In order to be a veritable maximum, the maximum must maintain its power, that is, a milieu of possibility spreading beyond its actuality. This ‘more’ is never something added from the outside. It is added from the principle (the center), which is the intrinsic fertility of the virtual. Rather than a background that is spread out, a diffused indefiniteness that envelops, the virtual enveloping is from a single point or two points: it is concentrated in the eyes of the omnivoyant. The omnivoyant envelops not because it is spread out like an enveloping fog, but because it is spreading out as possibility grows with actuality. Again, this shows that the icon, as a symbol of the virtual, is a mirror rather than a window:

the eye is like a mirror, and a mirror, however small, figuratively takes into itself a vast mountain and all that exists on the mountain’s surface .... Since (God’s) sight is an eye or a living mirror (speculum vivum), it sees all things in itself. Even more, since it is the cause of all that can be seen, it embraces (complectitur) and sees all things in the cause and reason of all, that is, in itself (DVD, 8 (30)).

The concentration in physical size does not limit the encompassing nature of the omnivoyant.

Cusa’s theory of space has less to do with extension than intension. In a sense, Cusa’s vision of space as contraction is the opposite of the modern visualization of space as geometrical extension. Space extends out from the eye so that the eye can then measure one thing against another. But for a radical perspectivism, extension, measuring movement, and distances, has no meaning in itself. Thus, space is conceived as the opposite of extension: contraction, where the circle whose center is everywhere and circumference nowhere does not extend out, but contracts: as a person, as a tree, as a universe. This contraction is expressed as seminal power. Space as formlessness, aptitude, lack (DI, II, 8 (133) is contracted into place rather than extended from or set out before the eye. Thus, the infinitude of creation lies in this intensified unity rather than in the infinite largeness of mathematically extended space. This substrate entails a re-imagined understanding of space implied in Cusa’s theory of contraction. The virtual milieu becomes a site or a place through solidification in concrete unities or finite infinities. Those who encircle the omnivoyant gaze are its circumference and its center at once. Thus, it is not a matter of the infinite as cause of the finite, but of an absolute maximum (all-possibility) that is approached by a contracted maximum. Each thing is a limited infinity: infinite as a whole with a certain coherence and power of self-actualization and of surpassing measurable or predictable possibilities. Yet, its infinity of power is intimately linked to its finitude as a contraction—a body in space having a particular perspective.

Enigmatic Mirroring: Being Seen as Milieu of Possibility

This section will conclude my exposition of Cusa’s thought with my own constructive addition to Cusa’s philosophy of seeing in light of the dynamics of contraction and the milieu of the virtual. This will allow me to follow with conclusions in the final two sections, first about the debate between Marion and Falque and second concerning Alberti and Cusa.

The omnivoyant gaze is linked to radical perspective because it is only by exceeding perspective (not by negating it) that the concept of omnivoyance becomes intelligible. Where the limited gaze either sees a singularity (when it is seen by another) or a totality (by means of objectification), one essential way it recognizes and thus surpasses its perspectivism is the concept of an omnivoyant gaze. Can we see from the perspective of an omnivoyant gaze? Of course not. But we can imagine the concept. Further, the dynamic between seeing and being seen, perspective and possibility, shows that we participate already in the infinity of perspectives that allows us to exit our own perspective. We will only surpass perspective by letting our seeing coincide with being seen, that is, hearing the voice of the other. Hearing the voice then allows us to ‘see’ from this new perspective. In short, activity and possibility grow together, which is to say that the overall dynamic at work here is not activating possibilities, but is contracting possibility-activity in a dynamic coincidence. We can now grasp the concepts of virtuality and contraction in their relation to the ground as milieu of vision. We can connect these concepts more closely with Cusa’s theology of vision itself, that is, with the coincidence of seeing and being seen.

First, I will give ‘seeing’ and ‘being seen’ a new definition within Cusa’s larger metaphysical framework. Then, I will be able to give a phenomenological description of the coincidence that makes sense of these definitions. Being seen is radical possibility: the possibility to exceed perspectival possibility. It coincides with hearing the voice of the other in order to extend beyond the possibilities of one’s own perspective. It is a power not without passivity although grammatically it occupies the place of a middle voice at least as much as a passive voice. Marion, for instance, recognizes a pure passivity to be invalid, since videri must also contain the meaning of to see yourself being seen: se voir vu not être vu (Marion 2016, p. 21). It is because it contains the meaning of a middle voice that the active and the passive are not merely reciprocal inversions, but entail a dynamic relation where videri is more than the object seen but is actually a milieu (a middle, a field) that videre inhabits and in which videre transforms itself and is transformed. Being seen is radical possibility because going beyond your own perspective is first of all to let yourself be seen by the other and to hear her voice. It is what I have already described with respect to the omnivoyant and the virtual, the matrix of the real, a space of inhabitation. Being seen is the milieu of vision itself. The definition of seeing, then, is seeing from a perspective. From these two definitions, we can derive an inference. If seeing coincides with being seen, now possibility coincides with perspective and radical perspective with radical possibility.

Because of its emplacement within a milieu, the relation must be thought not as a pure coincidence but as a dynamic coincidence. We could describe this phenomenologically in a way that Cusa does not. To see yourself being seen is fundamentally to feel yourself being seen, that is, to feel the gaze of the other, which always causes us to act differently than when we feel that we are alone. In this way, the feeling of being seen always moves us out of our own perspective as we sense the judgment, the love, the desire, the hatred, in short, the affect, of the other, and thus begin ourselves to judge and interpret the other’s gaze, and then, the other’s voice. It is only after we feel the meaning of a gaze as the vibrations of a voice that we then begin to feel the friction of one’s own body moving from one position to another. This movement of the body is not a passage from one geometrically definable position to another. It is an expansion and refinement of the body in the qualitative dimensions of space. The seeing that is entailed with this being seen is radical because it leaves a limited position behind by the reception of the voice and the deployment of the imagination. It cannot be separated from this radical possibility to be seen: to hear and to judge from within the milieu of radical possibility which is the totality of perspectives. The economy I have just described most easily fits the reception of and deployment of the gaze in the contracted world among contracted gazes but in relation to the absolute gaze. In other words, it has to do with an economy of refraction among points on the circumference of the circle that encircles about the omnivoyant. Language is like the refraction of the radiance of the omnivoyant image.

With respect to the absolute—looking toward the center as it were, rather than along the edges—a different analysis must be made, an analysis of reflection rather than refraction. God is not the object of vision, nor is he the subjective image of ourselves. Instead, he sees us in our seeing him. In other words, he reflects our gaze like a living mirror. Just as we do not see an image of ourselves as God, but see our true selves in God, so it would make no sense to reverse the dichotomy such that we are the objects of God’s vision. Objectively speaking, God’s vision is too indifferent to see us as objects. Indifferent in two senses: both (1) not different from us quantitatively (he is a point, a center that is everywhere, to which we have no comparative, measurable relation) and (2) exemplifying indifference in the qualitative sense of not seeking the kind of control or certitude that is sought by the gaze that sees objects: ‘Our eye must turn itself toward an object because of the quantum angle of our vision. But the angle of your vision, O God, is not quantum but infinite’ (DVD, 8 (30)). Precisely because the omnivoyant does not have a perspective, it gives itself as a type of indifference. The coincidence of seeing and being seen is the kind of knowing that is not a controlling or a determining, but a making: ‘creatures cannot exist except by your vision. If they did not see you who see they would not receive being from you. The being of a creature is equally your seeing and your being seen’ (DVD, 10 (40)). Thus, Nicolas concludes that even for God creating (seeing) coincides with being created (being seen): ‘the wall of the coincidence of creating with being created’ in which creating and being created alike are not other than communicating your being to all things so that you are all things in all things and yet remain absolute from them all. To call into being things which are not is to communicate being to nothing. Thus, to call is to create, and to communicate is to be created. (DVD, 12 (49)).

At the wall of coincidence creating and being created coincide in God, but Nicolas is quick to assert that beyond the wall God is beyond the coincidence of creating and being created ‘absolute and infinite, neither creating nor creatable’ (Ibid).

The human being, by contrast, is not beyond the coincidence of creating and being created. She exists as contracted body, not in the absolute. Her seeing/creating is from a limited perspective, and being seen/being created is her possibility as such (which is unlimited, though according to her proper seminality). With respect to the absolute center, everything is created by God. From within the contracted world, however, God seems to be created by our seeing him, where his creating (seeing us) coincides with being created (being seen by us/our seeing him). There is a sort of hinge where the absolute meets creation, God contracting his all-possibility. This hinge is Christ as God-man—absolute maximum and contracted maximum at once—and the Christic operation of the human being as man-God.Footnote 18 Possibility is our being seen (by the Father), but it manifests as our seeing (the filial operation of being sent), that is, as our perspective as such. Perspective is limitation in that it is the contraction of unlimited possibility. The relation of possibility and perspective, seeing and being seen, are inverted in God as left and right are inverted in a mirror. Possibility is his seeing and our being seen, while perspective is his being seen, our seeing. In God, being seen is perspective in the sense that it is the proliferation of the omnivoyant gaze into a multiplicity of gazes that look back. In God, seeing is possibility itself, the milieu of absolute possibility in which our seeing takes place.

The coincidence of perspective with possibility, seeing with being seen, entails a power to create not only for God, but also for humanity since the principle of limitation (perspective) coincides with the principle of de-limitation (possibility). Seeing is the limitation—the going out into the world from this or that particular viewpoint. Being seen is unlimited and infinite—the possibility of the reception of the unexpected gaze, the unhoped for voice by which the reflection of the omnivoyant refracts along the circumference through the created other. Indeed, the strangest thing about this economy is that the limiting principle (perspective) is actually the active part (seeing) while the passive part (being seen) is intrinsically infinite,; that is, it is the way limitation opens up onto the world beyond itself. Seeing is limitation because of its intensity. It does not extend space, but intensifies. Intense seeing is an enfolding limitation (the mirror that reflects all by taking in all). It coincides with an extensive being seen, which is the unfolding of possibility. They coincide in a non-comparative manner since the coincidence occurs at the maximum for each (radical possibility, radical perspective). This becomes evident when we realize that to see and to be seen coincide when seeing is contracted and to be seen is absolute: ‘For the likeness that seems to be created by me is the Truth that creates me, so that in this way at least I may grasp how greatly I should be bound to you, since in you being loved coincides with loving’ (DVD, 15 (65)). Contracted seeing (perspective) is the manifestation of an absolute being seen (the absolute possibility of the omnivoyant).

We arrive at a better vision of the truth, this reflection of ourselves in the omnivoyant, through the other’s voice, that is, through refraction by which we perceive another viewpoint. Just like the polygon comes closer to the circle the more sides it has, so an increase of refracted angles along the circumference of the infinite circle around the omnivoyant creates for us a closer approximation of ourselves, which is the truth of our image hidden in God. The community of gazes thus doubles back onto the increased realization of one’s own singularity which is both to see one’s true image more clearly, and to create it.

Conclusion I: Icons and Images

Because the omnivoyant neither transpierces the visible nor provides a window onto reality, but instead functions as a mirror, it is hard to argue that either Falque’s or Marion’s reading is entirely satisfactory. The omnivoyant mirrors back the gaze, and mirroring, for Marion, is associated only with conceptual idolatry (Marion 2012, pp. 11–15). I will thus make some brief remarks about the problems arising within this debate.

First Marion: when we examine his deployment of Sartre, we can see that Marion takes Albertian (Cartesian) space as the fundamental concept of space undergirding his phenomenology. Marion argues, with Sartre, that the ego entirely disappears when it is the one seeing. It only appears as ego when another regards it (Marion 2016, p. 24). The disappearance of the ego is, in the Sartrean model, eventually overcome by something (the other) that does not submit to Albertian space and thereby, mutatis mutandi, makes appear what had disappeared because it does not fit within such a concept of space. The real in-the-world ego, however, always has a where. In a world in which the ego is always in place as well as in space and cannot be removed for hypothetical experiment, it could never entirely disappear into a vanishing point (or into hyperbolic Cartesian doubt). Here, the dynamic between seeing and being seen that I outlined earlier provides a richer account of how ‘being seen’ gives us our identity not by preceding seeing (and thus preceding our appearance as an ego), but by co-originating with seeing. We should talk less about the ‘appearance’ of the ego through the gaze of the other, and instead about the realization or contraction of the ego’s power by means of a ‘being seen’ that launches it on the imaginative path toward radical perspective. There is no active-passive opposition in Cusa’s system because power (virtuality) comes first, which is to say that there is a dynamic emergence of seeing with seeing oneself seen. The categories of image and icon, in Marion’s sense of the terms, are from the beginning determined by Alberti’s concept of space and fit better within a post-Cartesian sense of space.Footnote 19 If the icon ‘transgresses’ the space of the idolatrous image with a ‘counter-gaze’ or ‘counter-intentionality,’ and the image is constituted immanently by perspectival technique, neither would allow for the indwelling and encompassing nature of the omnivoyant.

Now Falque: Following Panofsky, Falque suggests that while the icon absorbs me, Renaissance perspective includes me in the space represented, its de-theologized presentation of the world (Falque 2014, p. 50). The problem with this view, as I see it, is twofold. First, Renaissance perspective, if it de-theologizes the world in a certain way, does not thereby include the viewer and the viewed in the same space, as Hoff and Belting have shown (Hoff 2013, pp. 50–58; Belting 2011, pp. 129–163). It is not as if getting rid of an overwhelming divine advent and letting a peaceful immanent gaze govern the painting automatically includes that gaze in the space governed. In fact, the effect is quite the opposite. The viewer disappears into the vanishing point so that he can completely control the image. He controls the painting by exiting its space. The ego is removed from the spatial world of the viewed in precisely the same moment which removes transcendence, the alleged ‘theology.’ As the extensive Christology of the second half of De visione Dei makes evident, Cusa maintains a position deeply opposed to a point of view de-theologized for the sake of immanent control. Even if his theological position is not conservative per se, his understanding of the icon remains within the sacramental ontology of the high middle ages.Footnote 20

While I do not think the omnivoyant should be labeled an ‘image’ to the exclusion of ‘icon,’ Cusa is not simply explicating the economy of a traditional icon, or even the philosophical concept of the icon, as Marion’s argument suggests. The mirroring coincidence of seeing and being seen is hardly traditional. As I have argued, there is a particular dynamism between being seen and seeing that links being seen to radical possibility and to co-origination with seeing rather than to a way of being externally determined by the other. This dynamism includes another triangulation between the ego, the divine other as omnivoyant (reflected gaze), and the human other (refracted gaze). The dynamism of this co-origination is quite different than Marion’s and Sartre’s account insofar as being seen is not from elsewhere, but is radical possibility itself.

Conclusion II: Sacramental Metaphysics and Eschatological Metaphorics

I have outlined how the development of perspectival realism in Renaissance art was made possible by the reconstruction of space as a mathematical system of coordinates that could be mapped onto a flat surface to create an illusion of reality. We have seen how this has less to do with the development of scientific precision in optics than with (1) the conflating of scientific precision with a theory of pictures and consequently (2) the eventual replacement of geocentrism (a naive non-perspectivalism) with a new, but just as fixed center—the gaze itself—which, taking its place as a fixed center, (3) converts the measurable into the real. For Alberti, however, the mathematics includes a metaphorical meaning: the vanishing point as quasi-infinite.

The metaphysical difference between Cusa and Alberti is much more subtle than that of a mathematical objectification versus a sacramental ontology. The difference is that of a contracted maximum versus a metaphorical maximum. Both are revealed from a point (the vanishing point, the omnivoyant gaze). Here, I would like to invoke again Carman’s reference to Alberti’s ‘quasi-infinite’ triangle in which the vanishing point goes ‘almost’ to infinity. That Alberti uses the qualifier ‘quasi’ is not insignificant. Carman notes that in Alberti, the visual field is identified with the infinite insofar as the lines of perspective converge in a point, whereas in real, finite space, parallel lines never converge: ‘The entire structure is a device to set up a contradiction’ (Carman 2014, p. 19). Carman’s argument is fairly convincing at the level of demonstrating that Alberti’s primary goal is neither to create illusion nor to make geometry an all-determining a priori background of appearing. Yet, the difference between what Alberti meant to convey and the actual meaning conveyed in the medium must not be underplayed.

This first of all, because, as Cusa repeats throughout his oeuvre, there is no ‘almost’ infinite and secondly because it does nevertheless function precisely as a quasi-infinite and not a true infinite. The ‘quasi’ is key to a deeper analysis of the meaning of perspective. Cusa’s geometrical examples of how a polygon can never coincide with a circle and a curve can never coincide with a straight line shows that there is in fact no quasi-infinite. There is the comparative, which is a metaphorical substitute for the infinite, or there is the superlative that unites two infinities in a dynamic maximal relation. The more sides are added to a polygon the closer it comes to a circle, but so long as it remains polygonal it will never coincide with a circle (DI, I, 3 (10)). Since it will never become a circle no matter how many sides are added, it is never ‘almost’ a circle: ‘even though the multiplication of its angles were infinite, nothing will make the polygon equal to the circle unless the polygon is resolved into identity with the circle’ (Ibid). Only once you have ‘leapt beyond’ numerical sidedness toward infinite sidedness will the polygon coincide with the circle. The addition of sides does not get us any closer to that leap. Every finite polygon can be infinitely closer to a circle, thus every finite polygon is infinitely distant from attaining circlehood.