Abstract

Background

Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder defined by deficits in social interaction, communication, and restricted repetitive behavior. Research studies indicate that children with autism spectrum disorders suffer from more sleep problems than the general population.

Objective

The aim of the study was to investigate sleep problems in adolescents with Asperger syndrome (AS) or high-functioning autism (HFA) and to further examine the association between sleep problems and problem behavior as well as autism symptom severity.

Methods

In this study, 15 adolescents diagnosed with AS or HFA (aged between 10–19 years) and one parent of each answered questions about sleep and sleep disturbances.

Results

A high prevalence of sleep problems (80 %) was found. The most frequently reported sleep problems were insomnia symptoms (80 %) and parasomnias (53 %). More sleep problems were associated with decreased daytime functioning, more precisely with more externalizing problem behavior and a higher autism symptom severity.

Conclusion

The results suggest that sleep problems are common in adolescents with AS or HFA and are connected to lower daytime functioning. Therefore, in clinical practice, individuals should routinely be screened for sleeping difficulties.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Autismus ist eine neurologische Entwicklungsstörung, die sich durch Defizite in der sozialen Interaktion, Kommunikation und beschränkte, repetitive Verhaltensweisen kennzeichnet. Bisherige Studien zeigen, dass Kinder mit Autismus-Spektrum-Störungen unter mehr Schlafproblemen leiden als die allgemeine Bevölkerung.

Fragestellung

Das Ziel dieser Studie war die Analyse von Schlafproblemen bei Jugendlichen mit Asperger-Syndrom (AS) oder hochfunktionellem Autismus (High-Functioning-Autismus, HFA) und die Untersuchung des Zusammenhangs von Schlafproblemen zu Problemverhalten tagsüber und zu der Schwere der Autismussymptomatik.

Methode

Hierzu beantworteten 15 Jugendliche mit der Diagnose AS oder HFA (zwischen 10 und 19 Jahren) und jeweils ein Elternteil Fragen zu Schlaf und Schlafstörungen.

Ergebnisse

Es zeigte sich eine hohe Prävalenz von Schlafproblemen (80 %). Die am häufigsten genannten Schlafprobleme waren Insomnie- (80 %) und Parasomniesymptome (53 %). Ein höheres Ausmaß an Schlafproblemen hing mit verringerter Funktionalität tagsüber zusammen, genauer gesagt, mit mehr externalisierendem Problemverhalten und mit mehr und schweren Autismussymptomen.

Schlussfolgerungen

Die Ergebnisse dieser Studie zeigen, dass Schlafprobleme bei Jugendlichen mit AS oder HFA häufig auftreten und mit einem geringeren Funktionsniveau am Tage verbunden sind. Daher sollte in der klinischen Praxis routinemäßig das Vorliegen von Schlafproblemen überprüft werden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Autistic disorder/infantile autism

Autism is a neurodevelopmental disorder that is defined by the presence of deficits or unusual behavior within three domains: social interaction, communication, and restricted repetitive behavior. It usually begins in infancy, with an onset prior to 3 years of age [2]. Autism symptoms are usually persistent across time, although specific behaviors may change with increasing age [16]. In the International Classification of Disease 10 (ICD-10; [37]) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; [2]), autism belongs to the superordinate category of pervasive developmental disorders (PDD), sometimes named autism spectrum disorders (ASD), whereas in DSM-5, individuals with ASD must show specific symptoms very early in their life. These changes allow diagnosis to be made early on.

In addition to these autism-specific diagnostic characteristics, nonspecific symptoms such as phobias, sleep problems, eating disorders, aggressions, and self-harm are common [2]. With regard to prevalence estimations, the male/female ratio is 4:1, indicating that four-times more males than females are affected by infantile autism [8]. The average prevalence determined by Fombonne [8] is 20.6/10,000. Prevalence correlated significantly with year of publication, indicating an increase in prevalence estimates in the last 15–20 years [8]. Autism occurs on all intelligence levels, although many individuals are mentally retarded [16]. Autistic individuals who show cognitively higher scores of functioning (no mental retardation, IQ > 70) are commonly termed “high-functioning autists” (HFA). Epidemiologic studies of HFA are lacking, probably due to the fact that there is no separate diagnostic category in ICD-10, DSM-IV, or DSM‑5.

Asperger syndrome

Even though this subcategory has been deleted in DSM-5, according to DSM-IV [2] and ICD-10 [37], Asperger syndrome (AS) comprises autistic impairments in social interaction and repetitive restricted interests in verbally fluent individuals. In contrast to infantile autism, there is no clinically significant delay in the development of spoken or receptive language [2, 37]; qualities in language are rather relatively intact and often verbose [16]. Cognitive skills are developed age appropriately and intelligence is normal up to high [37]. There is no age restriction with regard to the onset of symptoms [2]. In addition to the specific diagnostic symptoms, motor milestones may be delayed and motor clumsiness is usual [2]. Phobias, sleep problems, depression, and aggression are further nonspecific symptoms [37]. With regard to prevalence estimations, there are approximately eight to one more males than females affected [37]. Epidemiology studies of AS are, however, sparse, probably due to the fact that it has been acknowledged as a separate diagnostic category only in ICD-10 and DSM-IV [8]. A small number of studies indicate that the prevalence of AS is lower than that for autistic disorder, with an estimate of nearly 6/10,000 [8].

Sleep problems in autistic children

Research studies indicate that children with ASD suffer from more sleep problems than the general population [7, 12, 23]. The prevalence of sleep problems in ASD ranges from 40 to 80 % [22, 23, 25, 26, 35]. According to parental reports, sleep onset and maintenance problems are the most common sleep problems in autistic children [12, 23, 26, 33]. Night wakings also occur frequently in children with ASD [35]. Periods of nocturnal awakening lasting from 30 min up to 2–3 h have been reported, where the child may vocalize or get up and play with toys or objects in the room [23, 28]. Sleep onset and maintenance problems mostly result in reduced total night sleep duration [12, 22, 23, 27]. Beyond this, studies have shown that children with autism suffer more often from bedtime resistance and sleep anxiety than typically developed children [12, 35]. Other less-frequently reported sleep problems in children and adolescents with ASD include circadian rhythm disturbances as characterized by irregular sleep–wake patterns, sleep onset-delay, early morning awakening [23, 24], and parasomnias [12, 24, 26, 28].

Some studies investigated the association of sleep problems in ASD with daytime behavior such as mental problems or autism symptom severity. They found significant correlations between internalizing and externalizing problem behavior and sleep problems in autistic children [23], particularly for reported sleep problems in the past and present, night wakings, and poorer sleep quality. Correlation coefficients for severity of past sleep problems and current sleep problems were higher for children with ASD than for children in the control group. Other studies found night sleep duration to be the best predictor for autism symptom severity [28]. The fewer hours a child suffering from ASD slept per night, the more severe the autism symptoms. Furthermore, overall sleep disturbance, delayed sleep onset, and short sleep duration correlate with all autism symptoms (stereotyped behavior, impaired communication, and impaired social interaction), as well as overall autism severity [33]. In conclusion, prior studies suggest that an overall lack of sleep in children with ASD may intensify most autism symptoms.

Paavonen et al. [22] compared the prevalence of sleep disturbances in children with AS to healthy controls using a self- and parent-report measurement for sleep problems. The sample consisted of 52 children with AS (5–17 years) and a healthy control group matched for age and gender. The results indicate sleep onset delay and night wakings, sleep-related fears, negative attitudes towards sleep, and shorter sleep duration in the AS group. Child-reported sleep problems were also more prevalent in the AS group than in controls. The authors suggest that further research on sleep in children with AS is necessary.

With regard to previous research on sleep problems in ASD, several limitations exist. First, most studies on children and adolescents used only parental reports to measure sleep problems, which can be a significant limitation [11, 23, 24, 27, 28, 33]. Studies with actigraphy showed that parents slightly overestimate sleep problems of their children suffering from ASD [10]. Additionally, in general, children’s and parents’ reports on sleep problems often differ significantly [19, 20, 30]. Second, most studies were conducted with toddlers and children [10, 15, 23, 27, 28, 35], while only few studies included adolescents [11, 22, 33] and no studies exclusively addressed adolescents. Third, studies generally investigate individuals with ASDs, but studies assessing sleep in individuals with a specific ASD, such as AS, are rare [22]. Consequently, current information on sleep difficulties in children and adolescents with AS is limited.

Aim of the study

The main objective of the current study was to further investigate sleep problems in individuals with AS by evaluating the prevalence of various sleep difficulties in a specific sample of adolescents with AS or HFA. Both adolescents and parents were included. Moreover, the correlation of sleep problems in adolescents with AS or HFA to problematic daytime behavior as well as autism symptom severity was investigated. Based on the abovementioned studies, a high prevalence of sleep problems and positive associations between sleep problems and problem behavior and autism symptom severity were expected.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited at the Westfälisches Institut für Entwicklungsförderung (WIE), an outpatient therapy center for children and adolescents with PDDs in Bielefeld, Germany. The adolescents attended weekly 2‑h sessions while getting one-to-one behavior therapy. A total of N = 15 adolescents aged between 10 and 19 years participated, who were diagnosed with AS (N = 11, 73.3 %) or HFA (N = 4, 26.7 %) according to ICD-10 criteria. Diagnosis was made by an independent child psychiatrist and confirmed by a psychologist at the WIE. Mean (M) age was 14.32 years (standard deviation, SD = 3.03 years). Regarding gender, 13 male (86.7 %) and 2 female (13.3 %) adolescents were included. Additional behavior problems were suffered by 60 %, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (33.3 %) and emotional disorders (13.3 %) being the most prominent. Additionally, one parent per adolescent (13 mothers, 1 adoptive mother, and 1 father) filled in questionnaires. The mean age of the parents was 45.87 years (SD = 6.66 years).

Measures

Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children

Sleep in adolescents was measured by the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC). The SDSC [5] is a parent- and self-report survey consisting of 26 items. Items are rated on a five-point scale. A total score and the following six subscales are calculated: disorders in initiating and maintaining sleep (DISM), sleep breathing disorders (SBD), disorders of arousal (DA), sleep–wake transition disorders (SWTD), disorders of excessive somnolence (DES), and sleep hyperhidrosis (SHY). A set of background questions about age, gender, school form, diagnosis, comorbidities, and further health impairments were also included for the parents.

Social Responsiveness Scale

Autism symptom severity was measured by the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS) [4], which is a 65-item parent-report survey. An overall autism index and the following five subscales were calculated: social awareness, social information processing, capacity for reciprocal social communication, social anxiety/avoidance, and autistic preoccupations and traits.

Child Behavior Checklist

Problem behavior was measured by the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), which is a parent-report questionnaire assessing internalizing and externalizing problem behavior [1]. Responses were rated on a three-point scale. Seven syndrome scales were calculated: anxious/depressed, withdrawn/depressed, somatic complaints, social problems, attention problems, rule-breaking behavior, and aggressive behavior. Syndromes are further summarized to provide scores for internalizing and externalizing behavior problems.

Sleep-related self-efficacy

The adolescents additionally filled in 10 items about sleep-related self-efficacy (SSE; e. g., item 8: “I can always manage to solve difficult sleep problems if I try hard enough”) based on the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE) of Schwarzer and Jerusalem [29].

Procedure

Prior to participation an information letter was handed out to all families fulfilling the age and diagnosis criteria. Written informed consent was obtained from parents and verbal approval from adolescents. Those families who had consented to participate received an information sheet and the questionnaires to be filled in at home via their therapists. One parent and the adolescent completed the questionnaires and returned the material either personally or via mail. The study was approved by the Bielefeld University Ethics Committee.

Data analysis

Total scores as well as subscale scores were calculated for the SDSC, SRS, and CBCL. Parents’ sleep-related information was transformed into t-values. Descriptive statistics were analyzed. As tests concerning normal distribution and histograms revealed significant deviations for all variables, the differences in mean values of sleep parameters were analyzed by Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Effect sizes are displayed in Cohen’s d. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated for all sleep and behavior data.

Results

Descriptive statistics

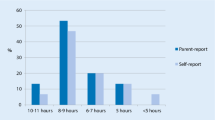

According to parental and self-reports (SDSC), the median sleep duration of adolescents with AS or HFA was 8–9 h of sleep per night. As presented in Fig. 1, according to parental reports, 33.3 % (N = 5) slept 7 h or less per night. According to self-reports, 40 % (N = 6) slept 7 h or less per night.

The medians of sleep onset latency were 15–30 (self-report) and 46–60 min (parental report). Falling asleep regularly took more than 30 min in 40 % (N = 6, self-report) and 66 % (N = 10, parental report) of the adolescents. According to parental reports, 80 % (N = 12) of the adolescents suffered from disturbed sleep. As presented in Fig. 2, the most common sleep problems were difficulties in falling and maintaining sleep (80 %, N = 12), disorders of arousal (53 %, N = 8) and sleep–wake transition disorders (53 %, N = 8). Disorders of excessive somnolence (47 %, N = 7) and sleep hyperhidrosis (47 %, N = 7) also appeared frequently. Sleep breathing disorders were reported in 13 % (N = 2) of the adolescents.

Comparison of parent- and self-reports of sleep problems

Mean sleep subscale scores for the parental and self-reports are presented in Table 1. Parents reported slightly more total sleep problems, disorders in initiating and maintaining sleep, and sleep hyperhidrosis; however, these differences were not significant (all p > 0.05).

Adolescents with autism reported significantly more disorders of excessive somnolence (Z = −2.24, p < 0.05, d Cohen = 0.60). Parents and adolescents did not differ in their report concerning sleep-related breathing disorders, disorders of arousal, and sleep–wake transition disorders. Correlation coefficients between parent- and self-reported sleep problems were calculated. The results of the Spearman bivariate correlations are displayed in Table 2, revealing low to moderate agreement [14].

The highest agreement between adolescents and parents was found for disorders of excessive somnolence and sleep hyperhidrosis. Significant correlations were also found for sleep breathing disorders, but not for disorders of arousal, disorders in initiating and maintaining sleep, sleep–wake transition disorder, or total sleep problems.

Sleep problems and problem behavior

Correlation coefficients between the seven SDSC scales (parent- and self-report of autistic adolescents) and the seven syndrome scales, the three broadband subscales, and the total problem score of the CBCL were calculated. With regard to the CBCL, significant correlations occurred for rule-breaking behavior (RBB), aggressive behavior (AB), externalizing problem behavior (EPB), and the total problem score. With regard to the SDSC (self-report), sleep breathing disorders, sleep–wake transition disorders, and total sleep problems were significantly correlated with problem behavior. Regarding the SDSC of parents, sleep–wake transition disorders significantly correlated with RBB (r = 0.52, p ≤ 0.05). Correlation coefficients for the SDSC (self-report) and the CBCL scales are displayed in Table 3. In detail, sleep breathing disorders correlated significantly with RBB, AB, EPB, and the total problem score, but not with any internalizing scale. Sleep–wake transition disorders correlated significantly with RBB, but with no other CBCL scale. Furthermore, disorders in initiating and maintaining sleep, disorders of arousal, disorders of excessive somnolence, and sleep hyperhidrosis were not associated with any CBCL scale. Last but not least, the total sleep problem score also correlated significantly with RBB, but with no other CBCL scale.

To further investigate the association between sleep problems and problem behavior, correlations between self-reported sleep hygiene and SSE and all CBCL scales were calculated. Results revealed no significant correlations between sleep hygiene or SSE and any CBCL scale.

Sleep problems and autism symptom severity

In a next step, correlation coefficients between the seven SDSC scales (self- and parental report) and the six SRS scales were calculated. Results showed that significant correlations only occurred for parental reports. Parent-reported disorders of arousal, sleep hyperhidrosis, and the total sleep problem score were significantly associated with autism symptom severity. With regard to the SRS, all subscales except for social information processing correlated significantly with at least one SDSC scale. Correlation coefficients for the SDSC (parent report) and the SRS scales are presented in Table 4.

Parent-reported disorders of arousal was significantly related to autistic preoccupations and traits; whereas sleep hyperhidrosis was significantly associated with social awareness, capacity for reciprocal social communication, and the overall autism index. The total sleep problem score was significantly correlated with capacity for reciprocal social communication, social anxiety/avoidance, and the overall autism index. The overall correlation between sleep problems and autism symptom severity was high (r = 0.56) according to Cohen [6].

Additionally, associations between sleep hygiene and SSE and autism symptom severity were examined. Therefore, correlations between self-reported sleep hygiene and SSE and the six SRS scales were calculated. There were no significant correlations between sleep hygiene and autism symptom severity. However, SSE was significantly correlated with autistic preoccupation and traits (r = 0.59, p ≤ 0.05), but with no other SRS scale.

Summary and discussion

The aim of the study was to investigate sleep problems in adolescents with AS or HFA and to further examine the association between sleep problems and problem behavior as well as autism symptom severity.

Congruent with prior research, the present study revealed a high prevalence of sleep problems in adolescents with AS or HFA. With a prevalence of 80 %, the frequency of sleep problems was slightly higher than in most studies concerning individuals with ASDs in general. For example, Patzold et al. [23] reported that 63.1 % of children with AS or autistic disorder suffered from disturbed sleep. Polimeni et al. [24] reported that in both autistic and Asperger’s individuals, 73 % have sleep problems, while Williams and colleagues found sleep problems in 53 % of children with ASD [35]. The prevalence of sleep problems in the present study was also higher than prevalence rates in studies with typically developing adolescents suggest, ranging from 16 to 33 % [15, 18]. Results of the present study support the assumption that sleep problems are significantly more frequent in adolescents with AS or HFA than in typically developing adolescents. Furthermore, sleep problems are slightly more prevalent in the special sample of adolescents with AS or HFA than in children with ASD in general.

In line with prior studies [11, 23, 26, 33], insomnias (difficulties falling and maintaining sleep) prove to be the most frequently reported sleep problem in the present study. Other commonly reported sleep problems were parasomnias, such as disorders of arousal and sleep–wake transition disorders. Parasomnias have also been identified as sleep problems in ASD by Hoffman et al. [22], Polimeni et al. [24], Richdale & Schreck [26], and Schreck & Mulick [27]. Polimeni and colleagues [24] even found parasomnias to be more prevalent in AS than in autistic disorder, supporting the findings of the present study. Daily somnolence was another sleep problem commonly mentioned by adolescents and parents (47 %). This result is congruent with that of Paavonen et al. [22], finding daily sleepiness to be frequently reported by children with AS. Other studies investigating children with autistic disorder [22] found only few reports of daytime sleepiness. The divergence of results leads to the assumption that daily somnolence may be more prevalent in individuals with AS than in autistic individuals. Furthermore, daily sleepiness was reported more frequently in self-reports than in parental reports [22]. In addition, the present study provides a new finding: sleep hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating) is a sleep parameter not often measured before. Nevertheless, this symptom was reported by almost 50 % of the parents in our study and was the fourth most often mentioned sleep problem. Paavonen et al. [22] have already found sleep hyperhidrosis to be more prevalent in children with AS than in typically developing children, underlining the importance of this rarely considered sleep parameter. Thus, excessive sweating should be considered as an important sleep problem in adolescents with AS, requiring further research. However, sleep breathing disorders were reported by only 13 % of the parents. This result is in accordance with the review by Richdale & Schreck [26] stating that symptoms associated with sleep apnea are only rarely reported in children with ASD.

To sum up, insomnia symptoms were the most commonly reported sleep problems, followed by parasomnias and daytime somnolence. They seem to occur slightly more frequently in AS and HFA than in infantile autism. Sleep-related breathing disorders were less common, replicating the results of studies with autistic children that also found sleep breathing disorders to be rare. Sleep hyperhidrosis seems to be an important sleep problem, and should be more closely examined in further research.

Self- versus parent-reported sleep problems

As an extraordinary component of this study, the accordance of autistic adolescents’ and parental reports of sleep problems was evaluated. Comparisons indicate that adolescents with AS or HFA report significantly more daytime sleepiness than parents do. Otherwise, no significant differences concerning sleep problems occurred between adolescents’ and parents’ ratings.

In line with previous studies [21, 30], the present study revealed only low accordance between parents and adolescents suffering from autism. Except for disorders of excessive somnolence, correlations between self- and parent-reported sleep problem scores were smaller than r = 0.70, indicating a low level of inter-rater agreement [13, 14]. Congruent with prior studies investigating the agreement of sleep reports between typically developing children and parents [19, 20], the highest agreement was obtained for sleep problems easily noticed by others, such as daytime sleepiness, excessive sweating, and sleep breathing disorders. Lower agreement was found for sleep onset and maintenance problems as well as for parasomnia symptoms like sleep–wake transition disorders. These results correspond to those of Owens et al. [19] also reporting large disagreement on insomnia symptoms (onset difficulties, night wakings). A negative correlation and therefore very small agreement was present for disorders of arousal, including nightmares, sleep walking, and night terrors. The results suggest that the disagreement is at least to a small extent related to parental awareness of sleep problems, because higher agreement was present for more obvious sleep problems. Paavonen [20] also found out that the inter-rater agreement between children and parents was negatively associated with children’s age. Possible reasons might be that parents are no longer involved in the bedtime procedure of older children. Therefore, it might be more difficult for parents to estimate insomnia or parasomnia symptoms like settling problems, night wakings, nightmares, or night terrors for older children or even adolescents.

In summary, the present study reveals a low level of agreement between AS or HFA adolescents’ and parents’ reports of sleep problems. The level of agreement seems to be related at least to a small extent to the parental awareness of sleep problems. The inter-rater disagreement of sleep problems seems to be similar for adolescents with AS or HFA and typically developing children.

Sleep problems and problem behavior

As hypothesized, sleep problems were positively associated with problem behavior. This result is in accordance with those of Patzold et al. [23]. Although the association between sleep difficulties and problematic daytime behavior was replicated, a few differences occurred: in contrast to Patzold et al. [23], no association between insomnia symptoms (onset problems, night wakings) and problem behavior was found. Furthermore, sleep problems were not associated with the total behavior problem score, but with externalizing problem behavior. These differences might be caused by several factors. First, different sleep parameters were implemented. While Patzold et al. [23] asked for sleep-related information such as co-sleeping with parents, total sleep problems in the past and present, and night wakings as single items, the present study used a standardized questionnaire to assess sleeping difficulties. Second, the samples differed concerning various parameters. While Patzold et al. [23] examined a sample of lower-functioning children aged around 7 years with ASD, the present study addressed higher-functioning adolescents with AS or HFA. Thus, the differences can at least to some extent be explained differing methodology.

In addition to the abovementioned findings, the present study revealed new results. In contrast to Patzold et al. [23], not only the association between sleep problems and the total behavior problem score, but also with all CBCL subscales was examined. Results indicate that sleep difficulties correlate with externalizing problem behavior, but not with internalizing problem behavior. Consistent with previous studies concerning typically developing adolescents [9], impaired sleep was mainly associated with rule-breaking behavior. This leads to the assumption that poor sleep quality in adolescents with AS or HFA is associated with a certain amount of irritation and aggression leading to increased externalizing behavior. The other way around, a higher level of irritation, concentration difficulties, and perhaps aggression (resulting in externalizing problem behavior) in autistic adolescents correlates with sleep problems. The present study reveals no information on whether the relationship between sleep problems and autism symptom severity is causal (in either direction). The relationship might also be due to a shared relationship with a third variable such as underlying neurological impairment contributing to both. For a better understanding of the relationship between externalizing problem behavior and sleeping difficulties in adolescents with AS and HFA, further research is required. Obviously, poor sleep is not connected to anxiety, withdrawal, or somatic complaints in higher-functioning autistic adolescents. Sleep breathing disorders and sleep–wake transition disorders were mainly connected to externalizing problem behavior. These results suggest that not quantitative sleep parameters such as sleep duration or night wakings, but other disruptions of the sleep process like sleep talking, sleep apnea, or repetitive actions while falling asleep relate to problem daytime behavior. However, these results are not congruent with studies concerning typically developing children [32, 34] and adolescents [36] that find insomnia as well as parasomnia symptoms to be associated with externalizing problem behavior. Further research on autistic individuals is needed to investigate whether the differences occur due to methodological reasons or really exist.

Sleep problems and autism symptom severity

As hypothesized, a positive association between sleep problems and autism symptom severity was obtained. Congruent with Tudor et al. [33] and Hoffman et al. [11], the total sleep disturbance score correlated significantly with impairments in social communication, social interaction, and the overall autism index. These findings support the assumption by Tudor et al. [33] that disturbed sleep might intensify autistic symptomatology during the day, not only in autistic children, but also in higher-functioning autistic adolescents. In contrast to Tudor et al. [33], the present study examines five instead of three autistic traits, revealing more specific results about which autistic traits might be intensified by sleep problems. Results indicate that disrupted sleep affects neither the capability to recognize social key stimuli nor the ability to interpret social key stimuli. Rather the competence to react adequately to social key stimuli was impaired. Furthermore, the autistic individual’s need of social interaction decreases with increased sleep problems. These findings suggest that prevention of sleep problems in adolescents with AS or HFA might increase both the individual’s need for and the individual’s competence in social interaction. Taking into account that both are essential for an age-appropriate social life, the importance of therapy of sleep problems in adolescents with AS or HFA is highlighted.

In contrast to prior studies, the total sleep problem score in the present study was not associated with autistic preoccupations and traits [11, 33]. Only the disorders of arousal scale is significantly correlated with autistic mannerisms. Moreover, neither insomnia symptoms nor shorter sleep duration nor sleep latency were associated with autism symptomatology. This result was contradictory to most previous studies [11, 28, 33]. Again, the differences can be partly explained by methodology. The samples of the abovementioned studies comprised mainly children, with mean ages ranging from 7.06 to 8.2 years, whereas the present study examines sleep problems in adolescents aged around 14 years. In addition, the previous studies included no [28, 33] or only very few [11] participants with AS. Consequently, it can be assumed that the association of sleep settling problems and sleep duration with autism symptom severity might be specific for lower-functioning children with infantile autism. For higher-functioning adolescents with AS or HFA, sleep parameters other than length of sleep were connected to autism symptomatology. Results of the present study show that sleep hyperhidrosis and disorders of arousal correlate with autistic traits, suggesting that qualitative disruptions of the sleep process were associated with autism symptom severity. Because there is no information about the causal relationship between sleep problems and autism symptom severity yet, two explanations are possible: either sleep disruptions increase the intensity of autism symptomatology during the day or, vice versa, autism symptoms intrude upon sleep. The causal connection should be further investigated in future studies.

The results also present new information on the association between autism symptomatology and SSE. SSE was significantly correlated to autistic preoccupation and traits, indicating that high sleep-related problem-solving competences correlate to a higher level of autistic impairment. However, this is the first hint that SSE has an impact on autism symptom severity and it can therefore hardly be interpreted. The connection between SSE and autistic symptomatology should be further investigated.

Limitations

The present study is the first to assess sleep problems in a specific sample of adolescents with AS or HFA, implementing both parents and adolescents concerning sleep of adolescents. Thus, this study provides important new information concerning sleep in higher-functioning autistic adolescents and its connection with daytime behavior. However, some limitations of the study are worth noting. First, the small sample size must be considered. Although there is a low prevalence of AS and HFA in the population, a larger sample size would be preferable—also for detecting statistical correlations which might have been overseen due to the small sample (type 2 error). However, other studies focusing on this topic also included only small sample sizes, since recruitment and prevalence rates are low (e. g., Patzold et al. [23], Hering et al. [10]). This study is a pilot study, providing first results of the association between sleep problems and behavior problems in higher-functioning autistic adolescents. Because of the small sample size, adolescents with additional behavior problems (e. g. ADHD) were not excluded from the study. However, most adolescents with AS or HFA suffer from other mental problems [31]. Therefore, this study can be seen as clinically relevant and representative of typical fields of AS or HFA. In addition, the present study did not provide a control group of healthy adolescents. Some similar studies with autistic children and adolescents also didn’t have control groups (e. g., Hoffmann et al. [11], Schreck et al. [28], Tudor et al. [33]). Regarding the measures, further limitations are apparent. First, there was no standardization and validation of the SDSC available. Second, children with an autistic impairment were asked about their sleep. Prior studies already found limited validity of self-reports of autistic individuals [3, 17], thus problems in understanding the questions need consideration.

Implications for future research

Results of the present study reveal a requirement for further research in this field. The findings should be replicated in a larger sample of adolescents with AS or HFA, with matched control groups of typically developing adolescents and adolescents with infantile autism. Moreover, longitudinal studies are required to analyze the causality between sleep problems and daytime behavior (problem behavior and autism symptom severity) in this sample. Furthermore, the study relied on subjective measures of sleep parameters (parent- and self-reports). Future research should include real-time measures such as sleep diaries, actigraphy, and videosomnography to independently confirm adolescents’ sleep patterns. Finally, future research will need to control for the impact of comorbidities, long-term medications, and chronic illnesses.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a high prevalence of sleep problems in adolescents with AD or HFA was found. The most frequently reported sleep problems were insomnias and parasomnias. Increased sleep problems were associated with decreased daytime functioning, more precisely with more externalizing problem behavior and higher autism symptom severity. Therefore, in clinical practice, all adolescents with AS or HFA should be screened for sleep problems.

References

Achenbach TM (1991) Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. Author, Washington

Berthoz S, Hill EL (2005) The validity of using self-reports to assess emotion regulation abilities in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Eur Psychiatry 20(3):291–298

Bölte S, Poustka F, Constantino JN, Gruber CP (2005) SRS: Skala zur Erfassung sozialer Reaktivität: dimensionale Autismus-Diagnostik. Hans Huber, Bern

Bruni O, Ottaviano S, Guidetti V, Romoli M, Innocenzi M, Cortesi F, Giannotti F (1996) The Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC) Construct ion and validation of an instrument to evaluate sleep disturbances in childhood and adolescence. J Sleep Res 5(4):251–261

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. L. Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale

Cortesi F, Giannotti F, Ivanenko A, Johnson K (2010) Sleep in children with autistic spectrum disorder. Sleep Med 11(7):659–664. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2010.01.010

Fombonne E (2009) Epidemiology of pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatr Res 65(6):591–598

Gregory AM, O’Connor TG (2002) Sleep problems in childhood: a longitudinal study of developmental change and association with behavioral problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41(8):964–971

Hering E, Epstein R, Elroy S, Iancu DR, Zelnik N (1999) Sleep patterns in autistic children. J Autism Dev Disord 29(2):143–147

Hoffman CD, Sweeney DP, Gilliam JE, Apodaca DD, Lopez-Wagner MC, Castillo MM (2005) Sleep problems and symptomology in children with autism. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 20(4):194–200

Hoffman CD, Sweeney DP, Gilliam JE, Lopez-Wagner MC (2006) Sleep problems in children with autism and in typically developing children. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 21(3):146–152

Lance CE, Butts MM, Michels LC (2006) The sources of four commonly reported cutoff criteria what did they really say? Organ Res Methods 9(2):202–220

LeBreton JM, Burgess JRD, Kaiser RB, Atchley EKP, James LR (2003) The restriction of variance hypothesis and interrater reliability and agreement: Are ratings from multiple sources really dissimilar? Organ Res Methods 6(1):80–128

Liu X, Uchiyama M, Okawa M, Kurita H (2000) Prevalence and correlates of self-reported sleep problems among Chinese adolescents. Sleep 23(1):27–34

Lord C, Cook EH, Leventhal BL, Amaral DG (2000) Autism spectrum disorders. Neuron 28(2):355–363. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00115-X

Mazefsky CA, Kao J, Oswald DP (2011) Preliminary evidence suggesting caution in the use of psychiatric self-report measures with adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord 5(1):164–174

Ohayon MM, Roberts RE, Zulley J, Smirne S, Priest RG (2000) Prevalence and patterns of problematic sleep among older adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 39(12):1549–1556

Owens JA, Spirito A, McGUINN M, Nobile C (2000) Sleep habits and sleep disturbance in elementary school-aged children. J Dev Behav Pediatr 21(1):27–36

Paavonen J (2004) Sleep disturbances and psychiatric symptoms in school-aged children. University of Helsinki (Doctoral dissertation)

Paavonen EJ, Aronen ET, Moilanen I, Piha J, Rasanen E, Tamminen T, Almqvist F (2000) Sleep problems of school-aged children: a complementary view. Acta Paediatr 89(2):223–228

Paavonen EJ, Vehkalahti K, Vanhala R, von Wendt L, Nieminen-von Wendt T, Aronen ET (2008) Sleep in children with Asperger syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord 38(1):41–51

Patzold LM, Richdale AL, Tonge BJ (1998) An investigation into sleep characteristics of children with autism and Asperger’s disorder. J Paediatr Child Health 34(6):528–533

Polimeni MA, Richdale AL, Francis AJ (2005) A survey of sleep problems in autism, Asperger’s disorder and typically developing children. J Intellect Disabil Res 49(4):260–268

Richdale AL, Prior MR (1995) The sleep/wake rhythm in children with autism. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 4(3):175–186

Richdale AL, Schreck KA (2009) Sleep problems in autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, nature, & possible biopsychosocial aetiologies. Sleep Med Rev 13(6):403–411

Schreck KA, Mulick JA (2000) Parental report of sleep problems in children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord 30(2):127–135

Schreck KA, Mulick JA, Smith AF (2004) Sleep problems as possible predictors of intensified symptoms of autism. Res Dev Disabil 25(1):57–66

Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M (1995) Generalized self-efficacy scale. In: Weinman J, Wright S, Johnston M (eds) Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs. NFER-NELSON, Windsor, pp 35–37

Schwerdtle B, Isele D, Roeser K, Schlarb AA, Kübler A (2010) Gesundheitsbezogene Lebensqualität im Kindesalter in Abhängigkeit des Schlafverhaltens anhand des Eltern- und Kinderurteils. Somnologie (Berl) 14(Supplement 1):33. doi:10.1007/s11818-010-0489-2

Simonoff E, Pickles A, Charman T, Chandler S, Loucas T, Baird G (2008) Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 47(8):921–929

Stein MA, Mendelsohn J, Obermeyer WH, Amromin J, Benca R (2001) Sleep and behavior problems in school-aged children. Pediatrics 107(4):e60

Tudor ME, Hoffman CD, Sweeney DP (2012) Children with autism sleep problems and symptom severity. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 27(4):254–262

Velten-Schurian K, Hautzinger M, Poets CF, Schlarb AA (2010) Association between sleep patterns and daytime functioning in children with insomnia: the contribution of parent-reported frequency of night waking and wake time after sleep onset. Sleep Med 11(3):281–288

Williams PG, Sears LL, Allard A (2004) Sleep problems in children with autism. J Sleep Res 13(3):265–268

Wong MM, Brower KJ, Zucker RA (2009) Childhood sleep problems, early onset of substance use and behavioral problems in adolescence. Sleep Med 10(7):787–796

World Health Organization (1992) The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. World Health Organization, Geneva

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

N. Thenhausen, M. Kuss, A. Wiater, and A.A. Schlarb declare that they have no competing interests.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Dieser Beitrag wurde bereits unter der doi 10.1007/s11818-016-0078-0 in Somnologie (2017) 21(Suppl 1): S28–S36 veröffentlicht.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thenhausen, N., Kuss, M., Wiater, A. et al. Sleep problems in adolescents with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Somnologie 21, 218–228 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11818-017-0126-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11818-017-0126-4