Abstract

Purpose

This study assessed health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of long-term breast cancer (BC) survivors diagnosed at early stages and compare with cancer-free, age-matched women.

Methods

The study population included BC survivors diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or breast cancer stages I-II, who had undergone lumpectomy/mastectomy, with time since diagnosis ranging from 9 to 16 years. Survey was conducted at two tertiary hospitals in 2020. Data for cancer-free female controls was randomly drawn from a population-based survey and age-, education-matched with 1 case: 3 controls ratio. Self-reported HRQoL was assessed using EQ-5D with five dimentions. EQ-5D utility index score was calculated. Difference in EQ-5D score was evaluated using the Tobit regression model with adjustment for other covariates.

Results

Of 273 survivors. 88% and 12% underwent mastectomy and lumpectomy, respectively. The mean (standard deviation, SD) age at survey was 57.3 (8.5) years old. BC survivors reported significantly more problems performing daily activities (11% vs. 5%, p < 0.001), pain/discomfort (46% vs. 23%, p < 0.001), and anxious/depressed feelings (44% vs. 8%, p < 0.001) relative to the controls. Difference in EQ-5D score between BC survivors and the general population was higher in older age groups. The overall EQ-5D score of BC survivors was statistically lower than that of the control subjects (adjusted \(\beta\)=0.117, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Long-term BC survivors who survived beyond ten years post-diagnosis experience more pain, anxiety, and distress, leading to an overall poorer HRQoL.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

This study suggest the importance of follow-up care, particularly focusing on pain, anxiety, and distress management to enhance the HRQoL of long-term BC survivors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With more than 2.3 million cases diagnosed in 2020 and 7.8 million survivors by the end of 2020, breast cancer (BC) has become the most prevalent cancer worldwide [1]. The implementation of national BC screening and enhancement in treatments has improved BC patients’ five-year and ten-year survival rates to 90.1% and 84.6% [2], respectively. Thus, more than two hundred thousand BC survivors were reported in South Korea [3]. In general, BC survivors might experience a wide range of adverse effects stemming from treatment [4]. Some of these effects last for a short period and have little impact on BC patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL); however, some patients suffer from long-term complications that affect their HRQoL.

Due to the increase in the BC survivor population, there has been considerable interest in their HRQoL several years after treatment, especially in those who had undergone surgery for breast cancer. Most previous studies on BC survivors’ HRQoL focused on the immediate period following primary treatment until five years post-diagnosis [5,6,7]. Few studies have assessed BC survivors’ status beyond ten years post-diagnosis [8,9,10]. Previous studies suggest that BC survivors’ HRQoL improves after treatment, allowing them to return to work and their daily routines [8, 11]. However, it is unclear if survivors’ HRQoL is comparable to that of the general population.

Recent cancer statistics have reported that the median age of onset of BC among Korean women is around ten years earlier [12] than that among women in other countries, including China [13] and the US [14]. Thus, long-term Korean BC survivors might have different characteristics from BC survivors in other countries due to the age gap at the onset of the disease. Meanwhile, the majority of breast cancer patients undergo either breast-conserving therapy or mastectomy as one of the treatment modalities. Despite the previous literature on the impact on HRQoL in the early years post-operative, knowledge regarding the long-term impact of breast surgery on HRQoL has remained limited. To better understand the status of long-term BC survivors, this study investigated the HRQoL of long-term survivors and the difference in HRQoL reported by the cancer-free general population.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedures

Two data sources were utilized in this study. The first data source consisted of information on 333 BC survivors who had been diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ or invasive breast cancer stages I to II between 2004 to 2011 at two tertiary hospitals in Korea, namely the National Cancer Center and Samsung Medical Center. These patients had been previously recruited for participation in cohort studies, and details regarding the initial recruitment process can be found elsewhere [15,16,17,18]. In 2020, the survivors were contacted and invited to take part in a long-term follow-up assessment in order to evaluate their status as long-term survivors. The mean (standard deviation, SD) time since cancer diagnosis to the long-term FU survey was 11.6 (2.7) and the median was 10 years (interquartile range 10–14 years). Participants who had been diagnosed at advanced stages or had a history of recurrence were excluded from the analysis. The final number of long-term BC survivors was 273 participants (Fig. 1).

In order to compare HRQoL of BC survivors, the control subjects were randomly selected from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) [19]. The KNHANES is a cross-sectional, nationally representative survey conducted by the Korean Center for Disease Control and Prevention to assess the Korean general population’s health and nutritional status. We used KNHANES data collected between 2015 to 2019. Women with a history of any cancer type and missing HRQoL measure were excluded. As previously documented in other studies [20, 21], both age and education level have been demonstrated to be associated with HRQoL, rendering them significant potential confounding factors affecting individuals' HRQoL. Given the disprepancy in age and education level distribution between the long-term breast cancer (BC) survivors and KNHANES data, we employed a frequency matching process to ensure that controls were matched to BC survivor cases based on both age and education level with a ratio of one case to three controls.

This study was approved by the National Cancer Center’s institutional review board (IRB approval number: NCC2019-0281). For breast cancer survivors, we obtained written informed consent forms directly from all participants in our study. The KNHANES data are de-identified and publicly available for research. We used a de-identified public version of the KHANES data provided by the Korean CDC.

Outcome measurement

Health-related Quality of Life. HRQoL was measured using the EuroQol 5-Dimension Questionnaire (EQ-5D). The Korean version of the EQ-5D has been cross-cultural adapted and validated in a previous study [22]. The five dimensions of EQ-5D corresponding to five items include mobility, self-care, daily activities, pain/discomfort, and depression/anxiety. Participants respond to the EQ-5D items in three levels: “no problems,” “moderate problems,” and “severe problems.” In this study, we categorized these responses into two groups: “non-problematic” and “problematic” (presenting either moderate or severe problems). To calculate EQ-5D utility index score, we applied the weighted quality values for the Korean population [23]. EQ-5D score ranges from -0.17 to 1, with a higher value indicating better HRQoL status [24]. For the EQ-5D index, a difference of 0.07 or higher is considered a meaningful minimal clinical difference [25, 26].

Covariate measurement

The socio-demographic factors assessed include age, marital status, household income, education level, and employment status. Health-related factors include comorbidity status, menopausal status, age at menopause, pregnancy history, and BMI. Marital status has two values, “married and living with spouse” and “other” (e.g., single, widowed). Education was categorized into no education or primary school, middle school graduate, high school graduate, university graduate, and graduate/post-graduate degree.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of differences in demographic characteristics was tested using Fisher’s exact test or a t-test where appropriate. We assessed differences between BC survivors and the general population in the following outcomes: reporting problems in the five EQ-5D dimensions and overall QoL measured by EQ-5D index. Due to the ceiling effect of the EQ-5D index, we implemented Tobit regression [27], considering the right censor of the scores and adjusted for other covariates in the model. The Tobit regression is a regression model utilized when there is censored data [27], and has been applied in previous studies [28,29,30]. The difference in EQ-5D index thus was modeled using the univariable and multivariable Tobit regression model. The factors adjusted in the multivariate model include education level, marital status, employment status, menopausal status, pregnancy history, obesity status, and comorbidity status.

In addition, we conducted further sensitivity analyses using two different matching approaches: age-matching only and selecting controls without any matching variables (random sample). More details regarding the sensitivity analysis can be found in the supplemental materials. All analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Figures were plotted using R software version 3.6.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). All analyses were conducted with a two-sided type I error and an alpha of 0.05.

Results

Of 273 BC survivors and 819 cancer-free control subjects, the mean (SD) age was 57.3 (8.5) and 57.2 (8.6) years old, respectively, and more than 70% were less than 65 years old (Table 1). Among BC survivors, the proportion of married and living with spouse women was significantly lower than that among non-cancer controls (71.8% vs. 79.7%, p = 0.003).

In terms of health-related characteristics, long-term BC survivors had a significantly higher proportion of menopausal women (83.2% vs. 73.6%, p < 0.001), younger age menopause (48.9 vs. 50.0 years old, p < 0.001), and later age at first birth (27.1 vs. 26.0 years old, p < 0.001). Further, the two groups had a similar proportion of common comorbidities, including hypertension, arthritis, diabetes, thyroid, depression, cataract, and allergic rhinitis.

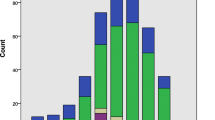

Among the EQ-5D dimensions, the two groups reported less problems in mobility, self-care, and usual activities dimensions in general. (Fig. 2) The long-term BC survivor group reported significantly fewer mobility problems (4% vs. 10%, p < 0.001) compared to the general population. However, BC survivors reported significantly more problems in daily activities (11% vs. 5%, p < 0.001), pain/discomfort (46% vs. 23%, p < 0.001), and anxiety/depression dimensions (44% vs. 8%, p < 0.001).

Differences in EQ-5D dimensions between long-term breast cancer survivors and the general population. P-values were obtained from Chi-squared test. The numbers of participants among breast cancer survivors who reported problem in five dimensions are as follows: mobility 12/273; self-care 3/273; usual activities 30/273; pain/discomfort 126/273; and anxiety/depression 121/273. The numbers of participants among general population who reported problem in five dimensions are as follows: mobility 80/819; self-care 22/819; usual activities 39/819; pain/discomfort 192/819; and anxiety/depression 65/819. BC, breast cancer long-term survivors; General: age- and education-matched general population

A significant difference in EQ-5D index scores between the two groups was observed across various demographic groups, and EQ-5D index scores of the BC survivors were lower than that of the general population. (Table 2) The difference in EQ-5D index score was higher in younger age groups: 0.015 in the age group ≥ 65 (p = 0.001), 0.044 in the age group 50 to < 65 (p < 0.001), and 0.049 in ≤ 50 age group (p < 0.001). Among participants with high school and university/post-graduate education levels, the EQ-5D index reported by long-term BC survivors was significantly lower than that reported by the non-cancer control group (difference 0.069, p < 0.001).

In the regression model, after adjusting for other covariates, long-term BC survivors had significantly lower EQ-5D scores than the general population with \(\beta\)=-0.117 (p < 0.001). (Table 3), Consistently, the sensitivity analyses yielded a significantly lower EQ-5D score in the long-term BC survivors compared with that of the general population. For more details, see Supplemental Table 1. BC survivors who exhibited arthritis (0.061, p < 0.001) and depression (0.094, p < 0.001) reported a lower EQ-5D score than individuals exhibiting no comorbidities.

Discussion

Although the negative effects of cancer persist long after treatment completion and have a detrimental impact on the HRQoL of cancer survivors, there is a lack of focus on the HRQoL of long-term survivors, especially those who have surpassed the ten-year mark since diagnosis. This study population possesses unique characteristics. First, it targeted early-stage BC survivors with long-term survival periods, ranging from 9 to 16 years since diagnosis. Moreover, considering the earlier age at which Korean women develop BC [12], the study focused on individuals diagnosed at a young age, with an average of 45 years. The extended survival time and early age at diagnosis of our long-term BC survivors distinguish our findings from previous studies and enhance the value to this research. Given the increasing number of long-term BC survivors and the scarcity of information regarding their HRQoL in comparison to the general population, our findings can help identify the extent to which the HRQoL of long-term BC survivors differs from that of age-matched women without a cancer history. Overall, our findings indicated that long-term survivors are more likely to experience pain, discomfort, anxiety and depression compared to their cancer-free counterparts. Additionally, they face greater difficulties in performing daily activities, such as work, housework, and family activities. Consequently, their overall quality of life (QoL) appears to be poorer than that of the general population, with a notable difference of 0.09 in the EQ-5D index. This evidence can be valuable in addressing the challenges faced by long-term BC survivors and providing essential information for the development of support programs tailored to this specific population.

We observed that long-term BC survivors have a significantly lower overall HRQoL compared to age-matched controls, with an effect size of 0.117. This difference, as found in our study, is both statistically significant and clinically meaningful, surpassing the minimal clinical difference of 0.07 for EQ-5D index [25, 26]. Consistent with previous research, our findings align with the notion that BC cancer survivors generally report poorer overall health status than the general population [31, 32]. For instance, a study focusing on long-term cancer survivors, more than five years post-diagnosis, discovered that these survivors experienced worse physical function, role, and emotional well-being compared to the general population[32]. However, it is worth noting that some studies have reported no significant disparities in overall HRQoL when comparing BC survivors with the general population [8, 9, 33].

Roughly half of the participants in our study reported experiencing moderate to severe pain and discomfort, which was 2.5 times higher than what was reported by women in the control group. Chronic pain, characterized as pain occurring on most days or every day over the past six months [34], is a prevalent long-term consequence of cancer treatment and has been linked to a decline in QoL [35]. Recent studies have indicated that 10% to 30% of cancer survivors suffer from chronic pain [34, 36]. Persistent pain among BC survivors can impede their ability to carry out daily activities, necessitating effective management strategies. Earlier research has also highlighted that BC survivors experience higher levels of pain intensity and unpleasantness compared to women in the general population. These factors are significantly associated with depressive symptoms, pain-related worry, and interference with daily functioning [37]. The observed disparities in pain experiences between BC survivors and women without a history of BC underscore the critical importance of proper chronic pain management in the survivorship phase.

In this study, long-term BC survivors reported a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety-related problems. This finding aligns with a previous study conducted on Korean BC survivors, which also reported higher levels of anxiety and depression compared to women without BC [38]. However, contrasting results were found in a recent cross-sectional study on Korean cancer survivors, where community-dwelling cancer survivors exhibited low depression scores, suggesting that depression is uncommon in this population [33]. Consequently, the evidence regarding depression among cancer survivors in comparison to the general population remains inconclusive. Furthermore, it is important to consider that self-reported depressive symptom may vary and should be understood within the appropriate context, which can differ based on ethnic and cultural factors.

Several limitations should be acknowledged in our study. Firstly, the HRQoL of BC survivors was assessed using the EQ-5D questionnaire. Although EQ-5D is widely used to measure HRQoL [19], concerns have been raised about its ceiling effects when employed in the general population [39, 40]. This issue was also evident in the KNHANES data, where 60.5% of participants reported a perfect EQ-5D score [41]. Therefore, caution should be exercised in interpreting the EQ-5D utility index scores in this study due to the potential ceiling effects. Secondly, the relatively small sample size prevented us from conducting further stratified analyses based on cancer stage or age at diagnosis. Thus, our results should be interpreted with caution, particularly because 90% of the study participants were BC stage 0 to II, indicating that they would generally have better HRQoL compared to patients with advanced-stage BC. However, despite the limited number of participants, our control group was representative due to the nationwide distribution of the KNHANES data, while the long-term BC survivor data were collected from two tertiary hospitals in Korea.

In conclusion, our findings offer valuable insights into the HRQoL reported by long-term BC survivors. We identified a significant disparity in pain and anxiety levels among long-term BC survivors, which adversely affected their overall HRQoL when compared to the general population. These findings have important implications for clinicians and healthcare providers in developing targeted long-term follow-up care for cancer survivors. Furthermore, the effective management of pain and psychological concerns should be a key focus in the design and implementation of survivorship programs for long-term BC survivors. By addressing these specific areas, we can strive to enhance the well-being and overall quality of life of individuals who have completed their BC treatment.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Sung H, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer J Clin. 2021;3:209–49.

Korea Central Cancer Registry, National Cancer Center. Annual report of cancer statistics in Korea in 2017, Ministry of Health and Welfare. 2019

Hong S, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2017. Cancer research and treatment: official journal of Korean Cancer Association. 2020;52(2):335–50.

Runowicz CD, et al. American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):43–73.

Yeung NCY, Lu Q, Mak WWS. Self-perceived burden mediates the relationship between self-stigma and quality of life among Chinese American breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(9):3337–45.

de Ligt KM, et al. The impact of health symptoms on health-related quality of life in early-stage breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;178(3):703–11.

Small BJ, et al. Cognitive performance of breast cancer survivors in daily life: Role of fatigue and depressed mood. Psychooncology. 2019;28(11):2174–80.

Hsu T, et al. Quality of life in long-term breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(28):3540–8.

Koch L, et al. Quality of life in long-term breast cancer survivors - a 10-year longitudinal population-based study. Acta Oncol. 2013;52(6):1119–28.

Ganz PA, et al. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: a follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(1):39–49.

van Leeuwen M, et al. Understanding the quality of life (QOL) issues in survivors of cancer: towards the development of an EORTC QOL cancer survivorship questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcome. 2018;16(1):114.

Kang SY, et al. Basic Findings Regarding Breast Cancer in Korea in 2015: Data from a Breast Cancer Registry. J Breast Cancer. 2018;21(1):1–10.

Zeng H, et al. Female breast cancer statistics of 2010 in China: estimates based on data from 145 population-based cancer registries. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(5):466–70.

Cancer Stat Facts: Female Breast Cancer. 2018. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html. Accessed 30 June 2020

Lee ES, et al. Health-related quality of life in survivors with breast cancer 1 year after diagnosis compared with the general population: a prospective cohort study. Ann Surg. 2011;253(1):101–8.

Mai TTX, et al. Prognostic Value of Post-diagnosis Health-Related Quality of Life for Overall Survival in Breast Cancer: Findings from a 10-Year Prospective Cohort in Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2019;51(4):1600–11.

Tran TXM, Jung SY, Lee EG, Cho H, Kim NY, Shim S, Kim HY, Kang D, Cho J, Lee E, Chang YJ, Cho H. Fear of cancer recurrence and its negative impact on health-related quality of life in long-term breast cancer survivors. Cancer Res Treat. 2022;54(4):1065–73. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2021.835.

Tran TXM, Jung SY, Lee EG, Cho H, Cho J, Lee E, Chang YJ, Cho H. Long-term trajectory of postoperative health-related quality of life in young breast cancer patients: a 15-year follow-up study. J Cancer Surviv 2023;17(5):1416–1426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01165-4

Kweon S, et al. Data resource profile: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(1):69–77.

Cho Y, et al. Factors associated with quality of life in patients with depression: A nationwide population-based study. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0219455.

Kim HJ, Chu H, Lee S. Factors influencing on health-related quality of life in South Korean with chronic liver disease. Health Qual Life Outcome. 2018;16(1):142.

Kim MH, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Korean version of the EQ-5D in patients with rheumatic diseases. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(5):1401–6.

Lee YK, et al. South Korean time trade-off values for EQ-5D health states: modeling with observed values for 101 health states. Value Health. 2009;12(8):1187–93.

Park JI, Baek H, Jung HH. CKD and Health-Related Quality of Life: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(6):851–60.

Walters SJ, Brazier JE. Comparison of the minimally important difference for two health state utility measures: EQ-5D and SF-6D. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(6):1523–32.

Pickard AS, Neary MP, Cella D. Estimation of minimally important differences in EQ-5D utility and VAS scores in cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:70–70.

Austin PC. A comparison of methods for analyzing health-related quality-of-life measures. Value Health. 2002;5(4):329–37.

Wijeysundera HC, et al. Predicting EQ-5D utility scores from the Seattle Angina Questionnaire in coronary artery disease: a mapping algorithm using a Bayesian framework. Med Decis Making. 2011;31(3):481–93.

Park S, et al. The impact of weight misperception on health-related quality of life in Korean adults (KNHANES 2007–2014): a community-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):e016098.

Abdin E, et al. Mapping the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale scores to EQ-5D-5L and SF-6D utility scores in patients with schizophrenia. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(1):177–86.

Annunziata MA, et al. Is long-term cancer survivors’ quality of life comparable to that of the general population? An italian study. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(9):2663–8.

Annunziata MA, et al. Long-term quality of life profile in oncology: a comparison between cancer survivors and the general population. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(2):651–6.

Lee SJ, Cartmell KB. Self-reported depression in cancer survivors versus the general population: a population-based propensity score-matching analysis. Qual Life Res. 2020;29(2):483–94.

Jiang C, et al. Prevalence of Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain in Cancer Survivors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(8):1224–6.

Paice JA, et al. Management of Chronic Pain in Survivors of Adult Cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(27):3325–45.

Gallaway MS, et al. Pain Among Cancer Survivors. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:E54.

Edmond SN, et al. Persistent Breast Pain Among Women With Histories of Breast-conserving Surgery for Breast Cancer Compared With Women Without Histories of Breast Surgery or Cancer. Clin J Pain. 2017;33(1):51–6.

Yu J, et al. Uneven recovery patterns of compromised health-related quality of life (EQ-5D-3 L) domains for breast Cancer survivors: a comparative study. Health Qual Life Outcome. 2018;16(1):143.

Luo N, et al. Self-reported health status of the general adult U.S. population as assessed by the EQ-5D and Health Utilities Index. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1078–86.

Wang H, Kindig DA, Mullahy J. Variation in Chinese population health related quality of life: results from a EuroQol study in Beijing, China. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(1):119–32.

Kang EJ, Ko SK. A catalogue of EQ-5D utility weights for chronic diseases among noninstitutionalized community residents in Korea. Value Health. 2009;12(Suppl 3):S114–7.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Center of Korea (grant numbers NCC-04101502 and NCC-1911271, NCC-2210880, NCC-2310450).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Thi Xuan Mai Tran: Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, formal analysis, writing–original draft; So-Youn Jung: Conceptualization, data curation, supervision, writing–review and editing; Eun-Gyeong Lee: Conceptualization, data curation, and writing–review and editing; Heeyoun Cho: Project administration, writing–review and editing; Na Yeon Kim: Conceptualization, project administration, writing–review and editing; Sungkeun Shim: data curation, writing–review and editing; Ho Young Kim: data curation, writing–review and editing; Danbee Kang: Conceptualization, data curation, writing–review and editing; Juhee Cho: Conceptualization, supervision, methodology and writing–review and editing; Eunsook Lee: Conceptualization, supervision and writing–review and editing; Yoonjung Chang: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, supervision and writing–review and editing; Hyunsoon Cho: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, supervision, writing–original draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the National Cancer Center’s institutional review board (IRB approval number: NCC2019-0281). The written informed consent forms were obtained.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Tran, T.X.M., Jung, SY., Lee, EG. et al. Health-related quality of life in long-term early-stage breast cancer survivors compared to general population in Korea. J Cancer Surviv (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01482-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01482-2