Abstract

Purpose

Little is known about the intersection between age and rurality as characteristics that impact lifestyle behavior change for cancer survivors. This review aims to summarize the current literature on lifestyle behavior change interventions conducted among rural survivors of cancer, with an emphasis on older survivors.

Methods

A systematic search of five databases identified randomized controlled trials and controlled clinical trials that targeted diet, physical activity, alcohol consumption, or tobacco use change in adult cancer survivors living in rural areas of the world.

Results

Eight studies met the inclusion criteria. Most studies were conducted in either Australia or the USA, included survivors at least 6 weeks post-treatment, and half included only breast cancer survivors, while the other four included a mix of cancer types. All but one had a physical activity component. No articles addressed changes in alcohol or tobacco behavior. Seven (87.5%) had a fully remote or hybrid delivery model. Most of the physical activity interventions showed significant changes in physical activity outcomes, while the dietary interventions showed changes of clinical but not statistical significance.

Conclusions

Few studies have been conducted to implement and evaluate the effectiveness of lifestyle behavior change interventions among older rural survivors of cancer. Future research should evaluate the acceptability and relevancy of adapted, evidence-based intervention with this population.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Effective diet and physical activity interventions exist, albeit limited in terms of effective lifestyle behavior change intervention tailored to older, rural survivors of cancer, particularly in relation to alcohol and tobacco behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the past decade, the average 5-year relative survival rate for all cancers combined has increased by approximately 20% [1]. This increase, which correlates with improvements in screening and treatment methods, has led to a rise in survivors of cancer [2]. In the next decade, it is expected that the number of individuals living with and beyond cancer will increase by 30% [3]. Survivors of cancer experience adverse side effects from their treatment that impact their quality of life and lifestyle behaviors, such as pain [4], fatigue [5, 6], and impaired functionality [7, 8]. More than 60% of the cancer survivor population is over 65 years of age, and estimates indicate that about 40% of all cancer survivors have survived for more than 10 years [2, 9]. Older survivors face a greater risk of comorbidity and co-occurring chronic disease than the general population [9].

One area of survivorship that is largely understudied is rural cancer survivorship. It is estimated that 20% of cancer survivors live in rural areas of the USA [10]. Rural populations tend to be older, have a higher prevalence of obesity and other comorbidities, lower cancer screening rates, and reduced access to healthcare services than urban populations [11,12,13,14,15]. Rural survivors of cancer commonly report their health as fair or poor rather than good or excellent [10] and have been shown to have lower physical functionality than urban survivors of cancer [16, 17]. As rural populations in general tend to be older and over 60% of cancer survivors are over the age of 65 years, it is likely that the intersection of age and rural living contribute to greater survivorship disparities for this population. This is a currently under studied area of cancer survivorship.

Based on a systematic review of the available evidence, the 2022 American Cancer Society Nutrition and Physical Activity Guideline for Cancer Survivorship recommends that cancer survivors follow a healthy eating pattern and engage in regular physical activity [18]. Lifestyle interventions to promote diet and physical activity after cancer have been shown to be effective broadly. Beyond demonstrated evidence that most interventions support positive changes in health behaviors such as diet and physical activity [19,20,21,22], systematic reviews have shown that interventions to promote healthy lifestyle behaviors among survivors of cancer, such as increased physical activity and improved dietary pattern, are associated with higher self-reported quality of life and functionality outcomes [20, 23,24,25,26]. Adherence to health-promoting behaviors has been reported to be low, especially among rural and older survivors [27,28,29]. Furthermore, delivering behavior change interventions for this population can be difficult due to barriers such as transportation distance, scarcity of health providers in the area, and lack of resource access [30, 31]. These are two populations of cancer survivors which have known disparities in health outcomes, yet little has been examined on the intersection of these identities and how adherence to health-promoting behaviors can be improved. The shifting population dynamics in cancer survivorship regarding both aging and rurality indicate that it is crucial to understand the health needs of this older, more vulnerable population if effective lifestyle interventions are to be developed and implemented.

To effectively intervene and promote health among rural cancer survivors, gaps in current evidence need to be systematically identified and evaluated. Recent reviews have highlighted the unique needs of rural breast cancer survivors [32] and behavioral interventions conducted with rural survivors of breast cancer [33]. However, these reviews fail to comprehensively examine the interventions conducted with rural survivors of any other cancer type. In addition, no review has specifically addressed the cross-section of rurality and older age of cancer diagnosis as common and novel characteristics that inform on intervention needs. The present systematic review was conducted to fill the gaps in each of these areas. While the eligibility criteria for included articles were intended to gather information for lifestyle behavior change interventions which have been conducted with rural cancer survivors, another unique aspect of this review is the opportunity to explore interventions relative to “older”—over age 65 years—cancer survivors and the intersection of rurality and older age given this is a priority research area for the National Cancer Institute [34]. We anticipate that this work will inform the future development of randomized controlled trials and controlled clinical trials that are evidence-based and effective in promoting healthy lifestyle behavior change for older, rural cancer survivors.

Aims

This review aims to summarize the current literature on lifestyle behavior change interventions (i.e., diet, physical activity, alcohol consumption, tobacco use) conducted among rural survivors of cancer, with an additional emphasis on older survivors. The goal is to assess the effectiveness of behavior change interventions and describe the demographic characteristics, intervention components, delivery methods, and measures used in lifestyle interventions for rural cancer survivors as well as to identify gaps in current evidence that will need to be addressed.

Methods

The conduct and reporting of this review adhere to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [35]. The protocol was registered with PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42021282313).

Search strategy

The following five electronic databases were searched in May of 2023 for relevant articles of all publications years: PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Education Source, Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE), and PsycINFO. The search strategy included Medical Subject Heading terms and keywords comprising (1) lifestyle behavior—diet, physical activity, smoking cessation, or alcohol consumption, (2) cancer survivors, (3) rural location, and (4) randomized controlled trials and controlled clinical trials. Filters applied to the search included randomized controlled trials, controlled clinical trials, adults, and humans, with no language restrictions. The search string (Supplementary Fig. 1) was developed in PubMed and translated to the other four databases.

Eligibility criteria

This systematic review includes randomized controlled trials and controlled clinical trials which examine the effect of lifestyle intervention on behavior change in four areas: diet, physical activity, tobacco use, or alcohol consumption. Supplementary Table 1 summarizes the eligibility criteria. Interventions were excluded unless they targeted at least one of these four health behaviors. Eligible studies included adult (18 years or older) survivors of cancer, defined as an individual from the point of diagnosis onward, of any cancer type living in a rural area of the world. Interventions that did not have a rural delivery focus or express the delivery of the intervention for participants living in rural areas were excluded. Rurality was determined via self-statement by the author, Rural–Urban Continuum Codes (RUCC), or Rural–Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes. The primary outcome measure of interest for this review was lifestyle behavior change. To be included in the primary analysis, studies must have reported at least two measurement timepoints of behavior, one pre- and one post-intervention. To provide further information about the delivery and acceptability of the intervention, details on behavior change goals, intervention delivery modes, intervention provider, sessions and duration, eligibility rate, recruitment rate, retention rate, and self-reported satisfaction or participant perspectives were gathered. Papers meeting the primary inclusion criteria were secondarily evaluated for age stratification or minimum age inclusion of 65 years or greater. Data specifically related to older adults were extracted, as available.

Study selection and data extraction

The authors, content experts with experience in systematic reviews and meta-analysis, developed a search strategy. A single individual (SW) performed the database search, and all citations were exported to EndNote X9 for data management. Duplicate citations were removed following the process described by Bramer et al. [36]. Two reviewers (SW, RR-M) then independently dual screened the titles and abstracts of all publications based on the eligibility criteria to select articles for full-text review. Articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded, and any articles for which there was a discrepancy between reviewers moved on to full-text screening for further review. The full text of the remaining articles was reviewed independently by two reviewers (SW, RR-M) to assess eligibility. Articles that did not meet eligibility criteria were excluded, and conflicting votes were adjudicated by a third reviewer (CT).

Outcomes

To describe the nature of the lifestyle studies among rural-dwelling adults who have survived cancer, we collected detailed information on intervention content, delivery, and outcomes. Data were extracted independently by SW and RR-M using an a priori designed data extraction form. Data collected from each trial included the following: (1) general study information (i.e., first author, year of publication, and location), (2) study design and behavior changes targeted, (3) eligibility criteria, (4) participant characteristics (i.e., sample size, age, sex, race), (5) intervention information (i.e., intervention delivery mode, intervention provider, sessions, and duration), (6) recruitment and retention details, and (7) details on behavior change goals (i.e., behavior change assessments and measures of effect). The effect size for the primary behavior change outcome, when reported, was described for each trial as it was reported by the authors.

Data quality

Two reviewers (SW, RR-M) independently assessed the quality of all included studies using the Cochrane Collaborations’ tool to assess risk of bias [37]. This tool includes five domains to assess the risk of bias and then rates the risk of each as low, high, or some concerns for each category. The five biases assessed were (1) selection bias (randomization and allocation concealment), (2) performance bias (blinding of participants and study staff), (3) detection bias (blinding of the outcome), (4) attrition bias (missing outcome data), and (5) reporting bias (selective outcome reporting). Each reviewer completed a risk of bias chart with these domains for each study, and any discrepancies were discussed and adjudicated by a third reviewer (CT).

Results

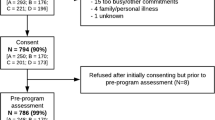

A total of 618 records were identified with 465 remaining after de-duplication. After title and abstract screening, 24 articles were identified for full-text review. Of these articles, 12 were deemed eligible based on the a priori criteria and were included in data extraction. An additional record was located through citation searching. The study selection process can be seen in detail in Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. Modified from: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Study characteristics

This review included a total of eight studies [30, 38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Four additional manuscripts, such as protocols, were reviewed for information about intervention details that were not reported in the included peer-reviewed manuscript [45,46,47,48]. While all studies were randomized controlled trials, four were described as two-arm randomized controlled trials [30, 38, 42, 43], three were described as quasi-randomized controlled trials [39, 40, 44], and one was described as a three stream-controlled trial [41]. Three were described as pilot or feasibility trials [38,39,40], and the other five were efficacy trials [30, 41,42,43,44]. Four studies took place in Australia [40,41,42, 44], one in Spain [39], and three in the USA [30, 38, 43]. Four studies recruited only breast cancer patients and survivors [30, 38, 39, 42], while the other four recruited a mix of cancer types, including colorectal, lung, prostate, gynecologic, head and neck, and lymphoma [40, 41, 43, 44]. Participants in three trials were still in active treatment [38, 40, 41], while participants in the other trials were at least 6 weeks post-treatment [30, 39, 42,43,44]. Two trials included both rural and urban or metropolitan survivors of cancer in the intervention [43, 44], while the other six only included rural participants. Overall trial enrollment ranged from 18 to 641 participants; four enrolled only females and the remaining enrolled 50% or more females. The age distribution across all studies ranged from 29 to 90 years, with three studies reporting an average age above 65 years [41, 43, 44]. Only four studies reported participant race and ethnicity. In all four studies, participants predominately identified as White (range: 86.9–100% White). Detailed characteristics from each included study can be found in Table 1. Specific diet and physical activity intervention characteristics and outcomes can be found in Table 2.

Intervention characteristics

While this systematic review aimed to examine lifestyle interventions that have been conducted concerning four different health behaviors (diet, physical activity, tobacco use, and alcohol consumption), no studies were identified that have targeted smoking or alcohol consumption in rural cancer survivor populations. Of the eight studies identified for this review, three targeted both physical activity and diet [30, 41, 43], four targeted only physical activity change [38, 39, 42, 44], and one targeted only dietary change [40].

Five trial designs and methods were guided by theories or frameworks [30, 38, 42,43,44]. Four studies used the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) [49] to guide their intervention [30, 42,43,44]. These studies focused on individual goal setting, self-efficacy, self-monitoring, and social support. The Steps TowaRd Improving Diet and Exercise (STRIDE) study incorporated the Self-determination Theory (SDT) [50] to support autonomy and allow the participants to choose which goal to work on [44] and the Reach-out to ENhancE Wellness (RENEW) trial [43] drew on the Transtheoretical Model [51]. The Living Well trial incorporated the Person, Environment, Occupation (PEO) Model of occupational therapy [52], meant to support the incorporation of activity that is meaningful and valuable to the participant, support identity, and reflect culture. A large focus of the trial was an adaptation to activity that reinforced these goals [38].

Given the challenges to delivering evidence-based interventions to populations living in rural areas, such as transportation and facility access [31], seven of the eight interventions utilized a home-based [30, 38, 42, 43] or hybrid delivery method [40, 44]. These interventions primarily utilized individual [38, 40, 42, 43] and group [30] telephone counseling as a way to provide greatest reach to rural areas and to support peer interaction for rural survivors. Interventions commonly incorporated mailed print materials [30, 38, 40, 42, 43], such as newsletters or workbooks, meal replacement shakes [30], and activity trackers as supplemental behavior change and study engagement strategies [42, 44]. The STRIDE trial was unique in the use of a website and emails to participants with weekly goals. The interactive website was used as a place for participants to record their steps taken and as a place for participants to interact with their peers in an online forum [44]. The I.CAN program was delivered in-person in the chemotherapy day unit where cancer patients were already traveling to receive care, thus not increasing the travel burden above their routine cancer care [41]. The physical activity intervention conducted by Santos-Olmo et al. in Spain included two supervised, in-person sessions and one unsupervised session [39]. Santos-Olmo et al. intended to minimize burden while maximizing potential impact by keeping the intervention under 5 weeks and creating a hybrid delivery model. In-person sessions incorporated exercise machines that participants could not access in a remotely delivered intervention. Importantly, the authors noted that while supervised sessions tend to show greater effect, unsupervised, home-based exercises are ideal as a tool for rural survivors to participate in long-term exercise programming.

Intervention duration ranged in time from 5 weeks [39], 8 weeks [40], 12 weeks [38, 41, 44], 8 months [42], 12 months [43], and 2 years [30]. The interventions were delivered primarily by health care professionals, including registered dietitians [30, 40, 41], psychologists [30], exercise physiologists [39, 41, 42], and occupational therapists [38]. The STRIDE study and the RENEW trial did not specify the qualifications of the intervention providers [43, 44].

Diet intervention and behavior change

Four studies targeted dietary change [30, 40, 41, 43]. Dietary change goals included change in energy consumption [30], increase in fruit and vegetable servings daily [30, 43], decrease in calories consumed from fat [30, 43], increase in the grams of fiber consumed [30], and change in nutritional status [40]. To measure these outcomes, studies utilized food frequency questionnaires (FFQ) [41], 24-h dietary recalls [30, 43], self-report food logs [30], and the patient-generated subjective global assessment (PG-SGA) [40, 53]. All four studies showed improvements in a priori outcomes in the direction of clinical interest after intervention, though these changes were not found to be significant. The Rural Women Connecting for Better Health trial showed significant weight loss among intervention participants, without significant change in self-reported dietary behaviors reported [30]. The I.CAN study reported an increase in positive food choices from 62% at baseline to 66% at 3 months [41]. The RENEW trial showed a 1.47 mean increase in fruit and vegetable servings and a 3.33 g per day mean decrease in saturated fat consumption for rural participants [43]. Finally, Brown et al. showed improvement in reported nutritional status after intervention [40].

Physical activity intervention and behavior change

Seven trials targeted physical activity [30, 38, 39, 41,42,43,44]. Goals for physical activity change included increase in moderate to vigorous aerobic physical activity (MVPA) minutes per week [30, 43], increase in step count [44], and increase in frequency of strength training [39, 42, 43] and aerobic exercise sessions [38, 39, 42]. These were analyzed using subjective measures such as the Paffenbarger Physical Activity Questionnaire [30, 54], the Godin Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire [41, 55], the Community Health Activity Model Program for Seniors Questionnaire (CHAMPS) [42, 43, 56], and the Active Australia Survey [42, 57]. Objective measures utilized include actigraphy [30], the Urho Kaleva Kekkonen Institute for Health Promotion research (UKK) test, which includes heart rate, Fitness Index, and VO2 max [39, 58], and a dumbbell and squat test to measure change in muscle resistance [39, 59, 60]. Four of the efficacy trials showed significant changes in physical activity or fitness outcomes post-intervention [30, 41, 42, 44]. The Rural Women Connecting for Better Health trial showed a significant increase in accelerometer-measured MVPA from baseline to 18 months (+ 19.7 min) [61]. The I.CAN trial found a statistically significant increase in exercise activity from 51% at baseline to 86% at 3 months (p < 0.001) [41]. The STRIDE trial showed a significant increase in mean steps per day for intervention participants from baseline to 12 weeks (+ 2219 steps) [44]. The Exercise for Health trial found odds of meeting intervention targets favored the intervention group for resistance training (OR 3.2) and aerobic (OR 2.1) activity [42].

Interface of age and rurality

Three studies reported participant mean age greater than 65 years [41, 43, 44]. Among these studies, only the RENEW trial included an a priori focus on older cancer survivors [43]. However, while this study did recruit and report outcomes for rural participants, rurality was not an inclusion criterion. The study included both urban and rural participants and did not tailor the intervention for rural delivery. Similarly, the STRIDE trial included both urban and rural participants, but did not tailor the intervention for either older or rural cancer survivors [44]. While the I.CAN trial was tailored for rural delivery, it was not tailored for older age [41]. The RENEW trial found that older and rural cancer survivors reported significantly more favorable mean changes in physical functioning (p = 0.015) and physical health (p = 0.044) than older and urban participants [43]. Lower percentages of rural participants met study goals related to fruit and vegetable consumption and saturated fat than urban survivors.

Risk of bias

Full risk of bias assessment can be seen in Fig. 2. Based on assessment from two independent reviewers (SW, RR-M), all included studies had at least some risk for concern or high risk of bias. For the randomization process, three studies were low risk of bias [42,43,44], one had unclear risk [30], and four had high risk of bias [38,39,40,41]. Allocation concealment was not well described in any trial; four studies had unclear risk [30, 42,43,44]; and four had high risk of bias [38,39,40,41] due to the ambiguity. Given the nature of behavioral interventions, blinding of participants and study staff was difficult, resulting in all studies having a high risk of bias. For blinding of outcome assessment, two trials had low risk of bias [42, 43], two had unclear risk [41, 44], and four had high risk of bias [30, 38,39,40]. Most studies had low risk of bias for incomplete outcome data and selective reporting. Only three had unclear risk of bias in these areas [40, 41, 44].

Discussion

This review highlights the current literature regarding physical activity and dietary interventions conducted with rural survivors of cancer. A key finding from this review is that the number of studies published on this topic is limited, and no studies addressing alcohol or tobacco use were identified. The trials reported suggested that the interventions were effective in promoting diet and physical activity change. Most interventions utilized a remote or hybrid delivery approach to reach rural participants. The majority of trials incorporated behavioral theory with most focusing on personalized goal setting and individual motivation for promotion of behavior change.

No lifestyle behavior change interventions were identified which set an a priori focus on the intersectionality of age and rurality in cancer survivorship. Only six studies tailored or designed the intervention for rural delivery, regardless of age. Given the known health inequities for older, rural cancer survivors, such as lack of access to healthy food, transportation barriers, lack of public infrastructure, and scarcity of health professionals [31, 62, 63], this gap in the literature must be addressed. The RENEW trial that enrolled older and rural (as well as urban) cancer survivors showed a significant improvement in physical functioning, as measured by the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36. It also demonstrated lower adherence to dietary change goals for rural versus urban participants [43]. This suggests that interventions which are shown to be effective for urban cancer survivors may not be as acceptable and/or effective for rural cancer survivors. Evidence-based interventions should be tailored and adapted for the needs of rural populations.

While there has been an overall increase in the use of telehealth methods for health promotion in the last decade [22], such as mobile app or internet-based interventions, access to broadband in rural areas is limited, and older survivors are less likely to use the internet [64, 65]. Though telehealth methods would appear to be ideal to overcome some barriers to rural intervention implementation, increased use of online platforms to promote behavior change interventions may leave older, rural cancer survivors behind, magnifying the health disparities faced by this population. This review highlights five interventions which utilized both individual and group telephone-based counseling [30, 38, 40, 42, 43], while only one, the STRIDE study, utilized an internet-based intervention [44]. The STRIDE study was conducted with both rural and urban participants and found that rural participants had lower engagement with the website than urban participants [44], possibly an indication of the need for specified technical support for rural participants. Telephone counseling appears to be feasible for rural intervention delivery. However, there is not enough research completed with mobile app or internet-based interventions to determine feasibility for older, rural cancer survivor populations. Preliminary research, though sparse, suggests that older and rural survivors of cancer are interested in adopting the use of mHealth tools to support self-monitoring of health and encourage health behavior change [66, 67]. For example, Ginossar et al. conducted interviews and focus groups with older, rural cancer survivors in New Mexico to explore perception of mHealth technology as a tool for health promotion. Participants identified that mHealth technology is compatible with behavior change goals, that the use of mHealth tools is advantageous over current methods for tracking health, and that the use of mHealth technology would increase motivation to change behaviors [67].

There is significant heterogeneity across the included studies that warrant further consideration. First, studies were conducted across the globe. This resulted in a wide variety of included measures for diet and physical activity that are difficult to compare without additional analysis. Considerations for cultural adaptation and resource availability will also vary based on geographic location. Second, studies recruited across the survivorship continuum, a dynamic period which includes both active treatment with curative intent as well as post-treatment care and follow-up. Survivors actively undergoing treatment may have different response to and acceptability of lifestyle behavior intervention compared to participants who are finished with active treatments. For example, survivors in the first-year post-treatment frequently report greater symptom burden than during treatment [68], a factor that may impact behavior change goal acquisition. As three of the included studies enrolled participants undergoing active treatment while the other five enrolled participants at least 6 weeks post-treatment, this difference in enrollment criteria may have implications for recruitment feasibility, retention, participant adherence to the intervention activities, and dietary and physical activity-related outcomes. Finally, half of the studies recruited only breast cancer survivors while the other four recruited across cancer types. This is not surprising as breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in women [1]. This review has indicated that there is a lack of evidence-based lifestyle behavior change programming for rural survivors diagnosed with non-breast malignancies and additional efforts are warranted.

Our initial search terms were selected to evaluate and describe literature about smoking and alcohol consumption in addition to diet and activity interventions; however, no interventions targeting these health behaviors were identified. For survivors of cancer, research shows that the risk of subsequent primary cancer is lower if the survivor quits smoking, even if they do not quit until after their first diagnosis [69]. Smoking and alcohol consumption also impact quality of life and cancer-related fatigue after cancer treatment [70, 71]. This lack of smoking and alcohol cessation programming adapted for rural survivors of cancer highlights a gap that should be addressed by future evidence-based interventions, especially due to the tobacco- and alcohol-related health disparities that are known to contribute to morbidity and mortality in rural areas [72,73,74,75].

The strengths of this review are that the inclusion criteria were not limited by language or publication year, allowing for the inclusion of one article published in Spanish [39] and a comprehensive search for any intervention conducted with rural survivors of cancer. While describing the effectiveness of these trials, this review also highlights key intervention characteristics used for dissemination and implementation and includes a novel focus on the intersection of age and rurality. As with any systematic review, one limitation is that there is a chance that some studies may have been missed using our search strategy. While the authors have experience in developing search strategies for systematic reviews and have been trained by research librarians, additional consultation with a research librarian may have further enhanced the thoroughness of the search. The limited number of studies identified and the diversity in the study methods, population, and settings limit the generalizability of the findings. As three of the studies were pilot or feasibility trials, they were likely not sufficiently powered to assess efficacy of the intervention and thus overall efficacy for lifestyle behavior change in rural cancer survivors is unclear. Additionally, many studies had a high risk of bias. It is difficult to conceal or blind study assignment when asking participants to change a behavior. This may have resulted in a Hawthorne effect or social-desirability bias as participants may have changed how they would otherwise behave because they were being observed. Another risk for the I.CAN trial was self-selection bias as participants were able to select which of the three arms of the trial that they would like to participate in. Interpretation of study findings should consider the generalizability of the data and real-world application.

Conclusion

In summary, this review identified that sparse research has been conducted to implement and evaluate the effectiveness of lifestyle behavior change interventions among older, rural cancer survivors, even though nearly 20% of cancer survivors live in rural areas of the country [10], 60% of survivors are over 65 years of age [2, 9], and there are known health disparities faced by these populations [27,28,29]. Future research should focus on the intersection of rurality and aging in cancer survivorship and determine the acceptability and feasibility of delivery methods and implementation strategies. Utilizing telehealth methods with rural cancer survivor populations, particularly older cancer survivors, to overcome barriers for implementing interventions in remote areas holds promise to improve the current state of wellness interventions and care in this underserved group of survivors. Given the limited availability of published work in this area, further qualitative and quantitative research to robustly describe the acceptability and feasibility of lifestyle behavior change interventions in this population are warranted. Future research should identify key considerations for adapting evidence-based interventions for delivery in rural areas and assess the fidelity of these adapted interventions.

References

Siegel RL, et al. Cancer statistics, 2021. Ca Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7–33.

de Moor JS, et al. Cancer survivors in the United States: prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2013;22(4):561–70.

Howlader N, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2009 (vintage 2009 populations). Bethesda: National Cancer Institute; 2012. p. 1975-2009.

Glare PA, et al. Pain in cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(16):1739–47.

Bower JE, et al. Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(4):743–743.

Berger AM, Gerber LH, Mayer DK. Cancer-related fatigue: implications for breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2012;118(S8):2261–9.

Bijker R, et al. Functional impairments and work-related outcomes in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28(3):429–51.

Kenzik KM, et al. Chronic condition clusters and functional impairment in older cancer survivors: a population-based study. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(6):1096–103.

Avis NE, Deimling GT. Cancer survivorship and aging. Cancer. 2008;113(S12):3519–29.

Weaver KE, et al. Rural–urban differences in health behaviors and implications for health status among US cancer survivors. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24(8):1481–90.

Cohen SA, et al. A closer look at rural-urban health disparities: associations between obesity and rurality vary by geospatial and sociodemographic factors. J Rural Health. 2017;33(2):167–79.

Long AS, Hanlon AL, Pellegrin KL. Socioeconomic variables explain rural disparities in US mortality rates: implications for rural health research and policy. SSM-Popul health. 2018;6:72–4.

Befort CA, Nazir N, Perri MG. Prevalence of obesity among adults from rural and urban areas of the United States: findings from NHANES (2005–2008). J Rural Health. 2012;28(4):392–7.

Savoca MR, et al. The diet quality of rural older adults in the South as measured by healthy eating index-2005 varies by ethnicity. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(12):2063–7.

Matthews KA, et al. Health-related behaviors by urban-rural county classification—United States, 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(5):1.

Silliman RA, et al. Risk factors for a decline in upper body function following treatment for early stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;54(1):25–30.

Miller PE, et al. Dietary patterns differ between urban and rural older, long-term survivors of breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer and are associated with body mass index. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(6):824-831.e1.

Rock CL et al. American Cancer Society nutrition and physical activity guideline for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(3):230–62.

Adams RN, et al. Cancer survivors’ uptake and adherence in diet and exercise intervention trials: an integrative data analysis. Cancer. 2015;121(1):77–83.

Pekmezi DW, Demark-Wahnefried W. Updated evidence in support of diet and exercise interventions in cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(2):167–78.

Terranova CO, et al. Dietary and physical activity changes and adherence to WCRF/AICR cancer prevention recommendations following a remotely delivered weight loss intervention for female breast cancer survivors: the living well after breast cancer randomized controlled trial. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2022;122(9):1644-1664. e7.

Roberts AL, et al. Digital health behaviour change interventions targeting physical activity and diet in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(6):704–19.

Speck RM, et al. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4(2):87–100.

Ferrer RA, et al. Exercise interventions for cancer survivors: a meta-analysis of quality of life outcomes. Ann Behav Med. 2010;41(1):32–47.

Fong DY, et al. Physical activity for cancer survivors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2012;344: e70.

Barchitta M, et al. The effects of diet and dietary interventions on the quality of life among breast cancer survivors: a cross-sectional analysis and a systematic review of experimental studies. Cancers. 2020;12(2):322.

Bellizzi KM, et al. Health behaviors of cancer survivors: examining opportunities for cancer control intervention. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(34):8884–93.

Blanchard CM, Courneya KS. Stein Kevin. Cancer survivors’ adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(13):2198–204.

Underwood JM, et al. Surveillance of demographic characteristics and health behaviors among adult cancer survivors—behavioral risk factor surveillance system, United States, 2009. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Recomm Rep. 2012;61(1):1–23.

Befort CA, et al. Protocol and recruitment results from a randomized controlled trial comparing group phone-based versus newsletter interventions for weight loss maintenance among rural breast cancer survivors. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;37(2):261–71.

Jong KE, Vale PJ, Armstrong BK. Rural inequalities in cancer care and outcome. Med J Aust. 2005;182(1):13.

Anbari AB, Wanchai A, Graves R. Breast cancer survivorship in rural settings: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(8):3517–31.

Ratcliff CG, et al. A systematic review of behavioral interventions for rural breast cancer survivors. J Behav Med. 2021;44(4):467–83.

Sedrak MS, et al. Older adult participation in cancer clinical trials: a systematic review of barriers and interventions. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):78–92.

Page MJ, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):89.

Bramer WM, et al. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104(3):240–3.

Higgins JPT, et al. The cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343: d5928.

Hegel MT, et al. Feasibility study of a randomized controlled trial of a telephone-delivered problem-solving-occupational therapy intervention to reduce participation restrictions in rural breast cancer survivors undergoing chemotherapy. Psychooncology. 2011;20(10):1092–101.

Santos-Olmo PA, Jiménez-Díaz JF, Rioja-Collado N. Efecto de un programa de ejercicio de corta duración sobre la condición física y la calidad de vida en mujeres supervivientes de cáncer de mama del ámbito rural: Estudio Piloto = Effect of a short duration exercise program on physical fitness and quality of life in rural breast cancer survivors: a pilot study. RICYDE Rev Int Cienc Deporte / Int J Sport Sci. 2019;15(56):171–86.

Brown L, Capra S, Williams L. A best practice dietetic service for rural patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy: a pilot of a pseudo-randomised controlled trial. Nutr Diet. 2008;65(2):175–80.

Ristevsk E, et al. ICAN: health coaching provides tailored nutrition and physical activity guidance to people diagnosed with cancer in a rural region in West Gippsland, Australia. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14(1):48–52.

Eakin EG, et al. A randomized trial of a telephone-delivered exercise intervention for non-urban dwelling women newly diagnosed with breast cancer: exercise for health. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43(2):229–38.

Gray MS, et al. Rural-urban differences in health behaviors and outcomes among older, overweight, long-term cancer survivors in the RENEW randomized control trial. Cancer Causes Control. 2019;30(4):301–9.

Frensham LJ, Parfitt G, Dollman J. Effect of a 12-week online walking intervention on health and quality of life in cancer survivors: a quasi-randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(10):2081.

Fazzino TL, Fabian C, Befort CA. Change in physical activity during a weight management intervention for breast cancer survivors: association with weight outcomes. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S109-s115.

Befort CA, et al. Weight loss maintenance strategies among rural breast cancer survivors: the rural women connecting for better health trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(10):2070–7.

Frensham LJ, et al. Steps toward improving diet and exercise for cancer survivors (STRIDE): a quasi-randomised controlled trial protocol. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:428.

Frensham LJ, Parfitt G, Dollman J. Predicting engagement with online walking promotion among metropolitan and rural cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2020;43(1):52–9.

Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action. Englewoods Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1986.

Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory. 2012;1(20):416–36.

Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12(1):38–48.

Law M, et al. The person-environment-occupation model: a transactive approach to occupational performance. Can J Occup Ther. 1996;63(1):9–23.

Bauer J, Capra S, Ferguson M. Use of the scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) as a nutrition assessment tool in patients with cancer. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56(8):779–85.

Paffenbarger RS Jr, et al. Measurement of physical activity to assess health effects in free-living populations. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25(1):60–70.

Shephard R. Godin leisure-time exercise questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29(6):S36–8.

Stewart AL, et al. CHAMPS physical activity questionnaire for older adults: outcomes for interventions. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(7):1126–41.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The Active Australia Survey: a guide and manual for implementation, analysis and reporting. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2003;49.

Oja P et al. UKK Walk Test, Testers guide. Tampere. 2006;3.

Pedrero-Chamizo R, et al. Physical fitness levels among independent non-institutionalized Spanish elderly: the elderly EXERNET multi-center study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55(2):406–16.

Rikli RE, Jones CJ. Senior fitness test manual. Human kinetics. 2013;2.

Fazzino T, et al. A qualitative evaluation of a group phone-based weight loss intervention for rural breast cancer survivors: themes and mechanisms of success. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(7):3165–73.

Ann Bettencourt B, et al. The breast cancer experience of rural women: a literature review. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16(10):875–87.

Ely AC, et al. A qualitative assessment of weight control among rural Kansas women. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41(3):207–11.

DeGuzman PB, et al. Beyond broadband: digital inclusion as a driver of inequities in access to rural cancer care. J Cancer Surviv. 2020;14(5):643–52.

Fareed N, et al. Persistent digital divide in health-related internet use among cancer survivors: findings from the Health Information National Trends Survey, 2003–2018. J Cancer Surviv. 2021;15(1):87–98.

Hardcastle SJ et al. Acceptability and utility of, and preference for wearable activity trackers amongst non-metropolitan cancer survivors. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(12):e0210039.

Ginossar T, et al. “You’re Going to Have to Think a Little Bit Different” barriers and facilitators to using mHealth to increase physical activity among older, rural cancer survivors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(17):8929.

Mayer DK, Nasso SF, Earp JA. Defining cancer survivors, their needs, and perspectives on survivorship health care in the USA. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):e11–8.

Tabuchi T, et al. Tobacco smoking and the risk of subsequent primary cancer among cancer survivors: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(10):2699–704.

Eng L, et al. Patterns, perceptions and their association with changes in alcohol consumption in cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Care. 2019;28(1): e12933.

Screening PDQ, Prevention Editorial B. Cigarette smoking: health risks and how to quit (PDQ®): Patient Version, in PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute (US); 2002.

Roberts ME, et al. Rural tobacco use across the United States: how rural and urban areas differ, broken down by census regions and divisions. Health Place. 2016;39:153–9.

Doogan NJ, et al. A growing geographic disparity: rural and urban cigarette smoking trends in the United States. Prev Med. 2017;104:79–85.

Buettner-Schmidt K, Miller DR, Maack B. Disparities in rural tobacco use, smoke-free policies, and tobacco taxes. West J Nurs Res. 2019;41(8):1184–202.

Friesen EL et al. Hazardous alcohol use and alcohol-related harm in rural and remote communities: a scoping review. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(2):e117–87.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Amanda Sokan and Dr. Zhao Chen for their topic expertise and feedback on early drafts of this manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the University of Arizona Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA023074).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design was completed by SJW with guidance from CAT and RR-M. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by SJW and RR-M. The first draft of the manuscript was written by SJW and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Conflict of interest

None

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Werts, S.J., Robles-Morales, R., Bea, J.W. et al. Characterization and efficacy of lifestyle behavior change interventions among adult rural cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01464-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-023-01464-4