Abstract

Marketing scholars have long acknowledged that buyer–supplier relationships (BSRs) evolve over time. Nevertheless, truly dynamic considerations tend to be confined to the “future research” sections of papers. Performing dynamic BSR research is difficult, not only because of the requirements of data collection and analysis, but also due to the somewhat fragmented understanding of the available studies on BSR dynamics and how an overarching understanding of their findings can refine static relationship models. We conduct a systematic literature review to organize the available research on BSR dynamics. The review process reveals four overarching themes: (1) relationship continuity, (2) relationship learning, (3) relationship stages and trajectories, and (4) relationship fluctuations. We discuss each theme, describe how the themes can be applied as a dynamic lens to research questions involving BSRs, and outline research directions that might stimulate further work on relationship dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A firm’s ability to successfully manage both its downstream relationships with buyers and its upstream relationships with suppliers is central to its competitive advantage (Flint et al. 2002). The marketing literature is replete with important and influential studies of buyer–supplier relationships (BSRs), unpacking the black box of the phenomenon by describing how the relationships between channels members fundamentally work. This is not surprising given how central these relationships are to the marketing discipline (e.g., Heide and John 1992; Moorman et al. 1992; Morgan and Hunt 1994). BSRs are “the vertical economic arrangements within any given dyad, ranging from market mediated to hierarchical transactions” that have implications for marketing channels, where each party is responsible for the relationship to some extent (Achrol et al. 1983, p. 55).Footnote 1 As fundamental as this relationship might be, our understanding of BSRs is still somewhat limited to a “snapshot of the level of relational constructs” (Palmatier et al. 2013, p. 24). In other words, our knowledge of BSRs from a descriptive standpoint is comprehensive, while our understanding is more circumscribed when it comes to understanding BSR dynamics, where relationship dynamics is defined as temporal variables, processes, or trends that explain a relationship’s development and change over time.

Taking a dynamic lens can begin to address a number of contested areas in research. Consider, for example, the research on the performance impact of relational governance (i.e., the reliance on norms and mutual trust) and formal governance (i.e., the reliance on rules and written contracts) within BSRs. Researchers have argued about whether these governance forms complement or substitute for one another (Dyer and Singh 1998; Poppo and Zenger 2002; Wuyts and Geyskens 2005; Carson and Ghosh 2019), debated the antecedents that affect their use (Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven 1996; Oh et al. 1992), and explored the contexts in which the complementarity effect will prevail (e.g., Mellewigt et al. 2007). While some scholars have nudged this field of research toward more dynamic considerations—including the influence of learning on governance choices (Joshi and Campbell 2003) or path dependent effects in their implementation (Bell et al. 2009)—the use of a dynamic lens has been sporadic at best.

Consider, as another example, the evidence on BSR relationship repair—the activities in which partners engage, following a transgression, to restore a relationship to a positive state (Dirks et al. 2009). Some studies take a dim view of the possibility of repair following transgressions (e.g. Dwyer et al. 1987; Wilson 1995), while others are less skeptical (e.g. Harmeling et al. 2015; Ring and Van de Ven 1994). Given the high stakes nature of many BSR relationships, the importance of knowing why “firms manage to put aside a disappointing history” to revitalize business relationships would appear to be critical (Jap and Anderson 2007, p. 273). Yet despite the “future” of troubled relationships depending on repair, this phenomenon has rarely been investigated from a dynamic perspective.

Given the importance of dynamic considerations in predicting future changes within relationships (Palmatier et al. 2013), a more systematic understanding of BSR dynamics appears overdue. Observing “that research integration and synthesis provides an important, and possibly even a required, step in the scientific process” (Palmatier et al. 2018, p. 1), our objective in this research is to address the shortcoming noted above by providing a systematic review of the literature on BSR dynamics.

In the following, we begin by providing an overview of relationship dynamics, highlighting existing approaches to studying them, and then draw from that overview to craft a clear definition of relationship dynamics. This overview is followed by a description of the method used for our systematic review to find literature that incorporates mechanisms that meet our definition.

Based on this review, we seek to make two fundamental contributions. First, we provide the first systematic review of the literature on BSR dynamics, revealing themes that yield a comprehensive set of variables that can inform dynamic relationship research. Our hope is that unearthing and categorizing a comprehensive range of dynamic variables might help shine new light on existing research questions where equivocal findings endure. Second, we then demonstrate the utility of this approach by applying the dynamic themes emerging from our review to the two contested areas of research outlined above. Specifically, we offer eight potential conceptual models by applying the four review themes to (1) relationship repair (e.g., Dirks et al. 2009; Tomlinson and Mayer 2009) and (2) the application of relational and contractual governance mechanisms within BSRs (e.g., Cao and Lumineau 2015). We also explore some implications of our themes for management practice.

Buyer–supplier relationship dynamics

The most prevalent theories that have been applied to understand BSR dynamics are transaction cost economics, social exchange theory, relational exchange theory, and relationship marketing theory (refer to the Web Appendix 1 for a complete list of theories). While transaction cost economics and relational exchange theory are inherently static (Williamson 1999), some efforts have been made to add dynamics to social exchange and relationship marketing theories (e.g., Harmeling et al. 2015; Palmatier et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2016). The results of these efforts have enabled dynamic BSR research to coalesce around some core theories, such as life-cycle theory (LCT) (e.g., Dwyer et al. 1987; Wilson 1995) and the theory of relationship development (TRD) (Ring and Van de Ven 1994). While these theories have begun to inform some more recent contributions to our understanding of BSRs in marketing (e.g., Harmeling et al. 2015; Palmatier et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2016), theories such as LCT and the TRD tend to be underutilized. As scholars begin to explore more dynamic conceptualizations of BSRs, it would seem that a review of how dynamic theories and frameworks (including LCT and the TRD) have been applied to BSR research is overdue.

Extant reviews of the BSR literature include both static and dynamic papers and focus on topics such as relationship formation or relationship structures; however, only a few of these papers have dedicated their reviews specifically to the question of relationship dynamics (Das and Teng 2002; Niesten and Jolink 2015; Shi et al. 2012). Indeed, while some reviews have been comprehensive in their treatment of the motivations, structures, strategies, and outcomes of interorganizational relationships, they have shied away from “portraying dynamic processes” inherent to all relationships (Gomes et al. 2016, p. 16). Some have ventured explanations for interorganizational relationship formation (i.e., the advantages and disadvantages of participating in interorganizational relationships), arguing that interorganizational relationships are comfortably predicted by a diverse range of organizational theories (Barringer and Harrison 2000). While relationship formation is an important component of a more dynamic understanding of relationships, questions about how relationships develop and evolve remain open. Indeed, Barringer and Harrison (2000, p. 396) themselves acknowledge that future research must identify the “management practices and techniques that facilitate the ongoing success of interorganizational relationships” (emphasis added).

Some reviews, however, have made a concerted attempt to apply a dynamic lens. For example, Das and Teng’s (2002) review examined alliances from a coevolutionary perspective drawing on developmental approaches (Ring and Van de Ven 1994). They were followed a decade later by Shi et al. (2012), who offered a temporal perspective on the interorganizational relationship literature. More recently, Niesten and Jolink (2015) considered the dynamic capabilities required of partnered firms to manage their relationships. While each of these papers has helped shape our understanding of the state of the art in dynamic approaches to interorganizational relationships, they have all focused exclusively on mergers and acquisitions and alliances, confirming Parmigiani and Rivera-Santos’s (2011, p. 1130–1131) concern that there are “considerably more reviews and studies describing horizontal dyads … rather than vertical relationships along the value chain.” Our study attempts to remedy these oversights by (1) broadening the means by which dynamics are understood within the literature and (2) focusing on the context of BSRs—interorganizational relationships that are most relevant to marketing.

To establish our definition of BSR dynamics and their mechanisms, we followed the “three [existing] dynamic relationship perspectives (age, stage, velocity)” (Palmatier et al. 2013, p. 15; “stage, age, velocity” in original), with each of them representing a separate group of dynamic studies. The first group of research studies on relationship development used variables related to age (i.e., duration of a relationship from its inception) as a proxy for the relationship status (e.g., relationship strength and the likelihood of continuation) or for reducing the rates of relationship dissolution over time (e.g., Anderson and Weitz 1989). However, other studies have been less certain about the effect of age on relationship outcomes (e.g., Anderson and Weitz 1992), leading to the claim that no two relationships of the same age are similar. Rather, in the second group of research studies on relationship development, relationships are seen as processes that are assumed to progress through sequential stages of development “according to a predictable, stable series of events occurring in a fixed order” (e.g., Jap and Anderson 2007, p. 262; Jap and Ganesan 2000), where the time required to pass through a particular stage might differ from one relationship to another.

In the final group of studies, researchers in social psychology use levels of relationship constructs and their temporal change (i.e., slope) to predict the future relationship status (i.e., stability), arguing that the ultimate relationship outcomes are better predicted by the slope of relationship constructs (Huston et al. 2001; Schoebi et al. 2012; Thibaut and Kelley 1959). More recently, a similar approach, under the umbrella term of velocity (i.e., the rate, or level, and the direction, or slope, of change in relationship elements), has been used to study BSR development (e.g., Harmeling et al. 2015; Palmatier et al. 2013).

Drawing on these insights, we define relationship dynamics as temporal variables (e.g., age, history, a shadow of the future, or long-term orientation), processes (e.g., life-cycle or cyclical changes), or trends (e.g., velocity or recent changes) that explain a relationship’s development and change. This definition accords with the Oxford Dictionary definition of dynamic as “a force that stimulates change or progress within a system or process.”

Scholars have considered temporal variables—or time-related elements—to develop a better understanding of BSRs. These include time-related variables captured at a specific point in time (e.g., relationship age) (Anderson and Weitz 1989) and variables that reflect a relationship’s past (e.g., prior exchange history) (Poppo et al. 2008) or future (e.g., shadow of the future) (Blumberg 2001). The use of these variables has enabled researchers to apply something of a dynamic lens to cross-sectional data.

We consider relationship processes to provide a more detailed focus on how BSRs change and evolve. Developmental relationship pathways (e.g., Narayandas and Rangan 2004) or the effect of path dependency among transactions over time (Bell et al. 2009) are two examples of relationship processes that have been of keen interest to scholars since Van de Ven’s (1976) seminal article on the nature, formation, and maintenance of relationships among organizations. He later noted that studies on the antecedents of BSR structures, while helpful, fundamentally “have not considered process, [which] is central to managing BSRs” (Ring and Van de Ven 1994, p. 91).

The final mechanism within our definition is relationship trends. Following Palmatier et al. (2013), we define trends as the recent magnitude (i.e., rate) and direction of the change in relationship elements. Studying trends is essential due to the disproportionate influence that perceptions of recent trends have on expectations of future continuity (Tversky and Kahneman 1986). Considering these studies should enable us to understand whether rate or trend—or both in combination—influences relationship development and change.

Method

The features of BSRs have long been of interest to scholars from diverse disciplinary backgrounds, including sociology, psychology, and economics, in addition to management and marketing. While this theoretical and disciplinary plurality has led to some intriguing insights, it also necessarily implies greater fragmentation of our understanding. This fragmentation underscores the need for a systematic synthesis of available research as, without such a synthesis, it is difficult “to know what we know” about the topic (Rousseau et al. 2008, p. 5). There is a risk of a misuse or underuse of research evidence or, conversely, an overuse of limited or inconclusive findings. Systematic reviews “summarize in an explicit way what is known and not known about a specific practice-related question” (Briner et al. 2009, p. 19) through “the systematic accumulation, analysis and reflective interpretation of the full body of relevant empirical evidence” (Rousseau et al. 2008, p. 3). A holistic understanding of relationship dynamics should help both scholars and practitioners by revealing the gaps for the former and synthesizing knowledge for purposeful application by the latter. This synthesis is important because despite their valuable contribution to theory and practice, static models can reveal only a snapshot of a relationship (Wilson 1995). To gain a fully formed understanding of BSRs, future research must draw from a broader suite of dynamic variables (Palmatier et al. 2013) that can help move inherently static theories and models toward more nuanced dynamic constructions (Williamson 1999).

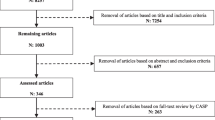

Our review involved several steps (see Fig. 1). We performed two searches in September 2017 and January 2020 using the EBSCO Business Source Complete database, which covers over 1300 scholarly journals and is one of the most complete databases for business studies (Zott et al. 2011). We did not restrict the output by date. In the first step, we used different forms (e.g., adjective, noun, or verb) and combinations (wildcard, proximity, and Boolean search) of various keywordsFootnote 2 for the abstract field, generating 29,139 scholarly (peer-reviewed) papers. We limited our search to a subset of journals that were most relevant to business studiesFootnote 3 and included a number of other journalsFootnote 4 that were relevant to our topic. Doing so narrowed the number of papers to 1627. The lead author conducted a title and abstract review of these papers, retaining studies that satisfied two criteria: (1) a focus on the dyadic BSR and (2) studies in which dynamism was among the main focuses of the argument. This process reduced the number of articles to 338.

The abstracts of these articles were checked for relevance by two of the coauthors, who acted as judges. They organized the articles into three categories: (1) “include,” (2) “exclude,” and (3) “maybe” (i.e., they were not able to definitively categorize the studies as “include” or “exclude” based on reading the abstract alone). Out of the 338 articles, the judges unanimously agreed on including 51 papers, excluding 193 papers, and placing 17 articles in the “maybe” category. They did not agree upon 77 articles, which resulted in a proportion of interjudge agreement of .77. To check the interjudge reliability level, we used the proportional reduction in loss (PRL) reliability measure, which “is a direct extension and generalization of Cronbach’s alpha to the qualitative case” (Rust and Cooil 1994, p. 9). The PRL reliability measure was .81, which is above the minimum requirement of .70 for exploratory work (Rust and Cooil 1994).

The research team agreed to exclude all 193 papers in the “exclude” category. The lead author was then charged with screening the full text of all papers in the “include” (51) and “maybe” (17) categories, as well as the 77 papers upon which agreement had not been reached, which we called the “disagreed” category (see Fig. 1). As a result, 30, 3, and 18 articles from the “include,” “maybe,” and “disagreed” categories, respectively, were selected. A careful reading of the reference lists of these papers revealed 61 additional articles that warranted closer inspection. Of these articles, 10 were considered relevant after a closer reading and were included in the final review, leading to the final number of 61 articles.

Research themes

Having identified and critically analyzed the relevant articles, we began our analysis by identifying our first-order categories through an open coding process of the core dynamic concepts within each paper. Next, we engaged in axial coding to find the relationships between the first-order concepts and to collapse them into second-order themes (Corbin and Strauss 2008). Through an iterative process of making comparisons and asking questions, we tried to find similarities between concepts and grouped them together into categories (Somekh and Lewin 2005). In the last step of this stage of analysis, we organized the second-order themes into overarching theoretical dimensions (codes are available in the Web Appendix 2) (Dacin et al. 2010). The following themes were identified: (1) relationship continuity, (2) relationship learning, (3) relationship stages and trajectories, and (4) relationship fluctuations. To ensure the validity of our identified themes, we engaged in peer debriefing, which involved checking the consistency of our codes to address the issue of the researcher’s reflexivity (Lincoln and Guba 1985). For this, we asked two scholars who are expert in the field of interorganizational relationships to judge the appropriability of our themes. They agreed with our orchestration of the themes, that they were distinct enough to be considered as separate themes, and that the themes were representative of the topic. Figure 2 illustrates the conceptual map of the reviewed papers with respect to their indicative themes.

Following the identification of our themes, we used two independent expert judges to code each of the 61 papers; both of our judges hold a Ph.D. in management and were working as research fellows with more than 20 years of research experience between them in management and marketing. Specifically, we provided them with the definitions of our themes and directed them to allocate each paper to one theme based on its relevance. We also asked them to introduce new themes whenever they judged the current themes as not representing the core dynamic idea of a paper. The expert judges found our identified themes to sufficiently cover all reviewed papers. Our judges performed this task separately without having contact with each other. They agreed on the categorization of 41 papers (out of a total of 61), which led to a proportion of interjudge agreement of .67. According to the PRL reliability measure (Rust and Cooil 1994), the interjudge reliability level for this level of agreement for two judges and four categories is .75, which is above the acceptable threshold of .70 for exploratory studies.

For each paper, where there was consensus between the judges, we allocated that paper to the agreed-upon theme; this was true for 41 papers. Where there was disagreement between the judges, we reached resolution through discussion (Hamilton et al. 2017).

Table 1 depicts the final results of this process (for a detailed overview of each paper, refer to the Web Appendix 1). Importantly, some of the papers used more than one dynamic mechanism (i.e., temporal variables, processes, and trends), which means that the total number of elements shown in Table 1 does not add up to the number of papers reviewed.

Relationship continuity

Perhaps the earliest, and certainly the most foundational, research in relationship dynamics involved exploring the factors that motivate firms to transition from a transactional focus to pursuing long-term BSRs (e.g., Ganesan 1994). As firms’ transaction horizons extend beyond the immediate, temporal considerations were brought into focus, including the probability of future exchange (e.g., Heide and Miner 1992; Kaufmann and Carter 2006), long-term orientation (e.g., Ganesan 1994; Lusch and Brown 1996), and perceived relationship continuity (e.g., Anderson and Weitz 1989). Within this broad category of BSR dynamics, we observed two themes: (1) the endogenous and exogenous drivers of continuity and (2) positive and negative self-referential effects of the expectation of continuity.

Turning to the drivers of continuity, we first observed exogenous variables that lie beyond the control of parties to the relationship or are generally applicable to any relationship. Some of these variables (e.g., high stakes, temporary de-embedding, or the complexity of a purchase) positively affect relationship continuity, while others (e.g., negative reputation, power imbalances, or market uncertainty) were found to have negative effects on continuity (Anderson and Weitz 1989; Kaufmann and Carter 2006; Poppo et al. 2008; Brattström et al. 2019). Other findings focused on the endogenous—that is, firm-level or managerially relevant—variables that affect relationship continuity, both from one side of the relationship dyad or jointly determined within the dyad, and that lead to sustainable competitive advantage (Ganesan 1994). These variables include trust (i.e., credibility and benevolence), dependence, and transaction-specific assets, each of which affect the perception of the long-term orientation of involved parties (Ganesan 1994; Lusch and Brown 1996; Poppo et al. 2008).

The second stream of research investigated the positive and negative self-referential effects of the expectation of continuity—that is, how the expectation of continuity itself defines future continuity. The key finding in this area of research demonstrates that expectations of continuity—a so-called “shadow of the future”—increase mutual investment in the relationship, cooperation, coordination and trust while also decreasing role ambiguity (Heide and Miner 1992; Poppo et al. 2008; Ren et al. 2010).

In contrast, Grayson and Ambler (1999) explored the idea that longer-term relationships—characterized by high trust, interaction, and involvement—do not necessarily enjoy greater relationship benefits due to the mediating effects of greater levels of opportunism, a loss of objectivity, and rising expectations. The results of their study were mixed, and nearly a decade later, Poppo et al. (2008) showed that when parties did not expect continuity for their long-term relationships, trust itself diminishes due to the parties’ increased motivation to act opportunistically or their reduced effort to adapt to new circumstances. It appears that the contrast between these results stems from their different views of the development of trust. Grayson and Ambler (1999) argue that a high level of trust in developed relationships should prevent opportunistic acts, while Poppo et al. (2008) contend that not only does trust not support a long-term relationship with a limited future horizon, but the lower level of trust itself also motivates transgressions.

Relationship learning

Learning is a dynamic notion due to its iterative, time-dependent nature, and it is realized through different mechanisms (Bell et al. 2002) that lead to ongoing changes both to organizations (Miner et al. 2001) and to relationships themselves (e.g., Lipparini et al. 2014; Mayer and Argyres 2004). These changes might be incremental or punctuated and are a function of new insights, capabilities, or routines (e.g., Amit 2016; March 1991). Our review revealed three approaches to relationship learning: (1) the effects of learning and memory updating on relationship governance choices, (2) knowledge sharing processes and their effects on the performance of BSRs, and (3) the speed of information sharing between firms.

Learning-focused studies of BSRs have primarily investigated how learning affects the trend and properties of organizational memory within business-to-business relationships (Flint et al. 2002) by updating contracts as repositories of previously learned materials (Argyres et al. 2007; Mayer and Argyres 2004). Through these memory updates, parties learn to substitute or complement governance mechanisms (e.g., formal and informal) with one another (Li et al. 2010; Weber 2017). For example, “partner experience may both reduce the need for control and provide enhanced supplier information that facilitates control design” (Dekker and Van den Abbeele 2010, p. 1246), while a relational mechanism such as trust might complement a contract and eliminate the need for more details in, or even substitute for, some contract provisions when the same parties are signing a new contract (Ariño et al. 2014; Weber 2017).

A further stream of research has focused on the fundamental processes of knowledge sharing and their effects on the performance of BSRs. These studies have mostly applied temporal variables, arguing that with age, relationships develop relational capital, which increases knowledge exchange efforts and mutual learning. These same studies, however, have found that self-interest also increases with relationship age, which can progressively reduce the knowledge exchange between buyers and sellers. Furthermore, any knowledge that is exchanged will tend to be used to pursue long-term goals outside the focal relationship (Im and Rai 2008; Lui 2009). Other studies have shown that contextual factors, such as a country’s culture, will moderate the amount of information shared by organizations as relationships age (Kotabe et al. 2003).

Finally, Lipparini et al. (2014) showed that the speed of information sharing is as fast as the weakest link in a network and, furthermore, that this factor influences a network’s ability to innovate or lower the cost of communication. These findings provide insight into why some dyads perform better and are more successful in reaching their strategic goals than others (Dyer and Nobeoka 2000; Zollo et al. 2002).

Relationship stages and trajectories

The third group of studies considers how relationships develop through stages or various trajectories (e.g., cycles and spirals). The research in this group fell into three main categories: (1) relationship development through stages and cycles, (2) relationship trajectories and trends, and (3) the emergence of relationships’ initial conditions through spirals (i.e., reciprocal causation between variables over time).

Researchers have tended to adopt one of two approaches to relationship stage development over time. In the first school of thought, a few papers (e.g., Jap and Anderson 2007; Vanpoucke et al. 2014) lean on the work of Ring and Van de Ven (1994)—the paper to which the TRD traces its origins—which defines the process of relationship development as a repetitive cycle of negotiation, commitment, and execution. The second school of thought, which is far more common, is found in a life-cycle tradition that holds that relationships progress through a sequence of stages whose characteristics (i.e., relationship elements such as trust and commitment) emerge or change with each stage (Dwyer et al. 1987; Frazier 1983; Heide 1994; Weitz and Jap 1995; Wilson 1995; Zajac and Olsen 1993); subsequent research has used a subset of these studies under the banner of LCT.

One of the most widely referenced studies in LCT explains how interorganizational relationships change across five stages (Dwyer et al. 1987). The authors of that study argued that relationships are bound to go through several stages, with relationship elements (e.g., commitment or trust) in this model progressing through an inverted U-shaped trajectory over time; measures of relationship quality progress from low levels in the early stages to reach a pinnacle at mid-relationship before declining through the final stages. The framework helpfully considers nuance in the effectiveness of relationship elements across stages (e.g., trust is important at the beginning of a relationship even though there is likely to be little trust between parties) (Weitz and Jap 1995; Wilson 1995); subsequent studies have defied this assumption by showing the importance of relational governance, such as altruistic trust (Lee et al. 2004), and its complementarity with contractual mechanisms (Cao and Lumineau 2015) in older relationships. However, the framework is somewhat deterministic; declining relationships are considered challenging to revive and, thus, candidates for termination. Stages can be distinguished from each other based on their unique sets of relationship characteristics, and there is an alignment between the choice of governance mechanisms and relationship characteristics across stages (Jap and Ganesan 2000).

The assumption of an inverted U-shaped trajectory to describe relationship development has been subject to criticism. There is evidence to suggest that some relationship variables, such as commitment, progress through inverted U-shaped trajectories (Palmatier et al. 2013). Other studies demonstrate the possibility of both backward trajectories (i.e., relationship elements reverting to levels at previous relationship stages) (Ring and Van de Ven 1994) and forward trajectories, which suggests the likelihood of iterative cycles (spirals) within a relationship (Jap and Anderson 2007; Vanpoucke et al. 2014). Perhaps the difference between the TRD and LCT lies in their consideration of the level of analysis; in the TRD, which emphasizes role theory, interpersonal relationships play a central role, while in the LCT framework, they are more of a peripheral consideration. In this regard, there is a stream of research on intimate relationships within social psychology that may be instructive for studying relationship trajectories. These studies consider specific periods (i.e., courtship, honeymoon, and marriage) and fluctuations and illustrate unique relationship trajectories for each relationship (e.g., Huston et al. 2001; Karney and Bradbury 1995). This stream of research complements the TRD arguments regarding the possible existence of trajectories specific to each BSR.

Nevertheless, it remains unclear what instigates the move from one stage to another in relationships. In a recent study, Zhang et al. (2016) provided some answers, introducing a modified set of relationship stages by separating the levels of relationship variables from their changing patterns. They identified the levels as relationship stages and the changing patterns as migration mechanisms, showing that different positive migration strategies (e.g., product mix, communication, or investment) or negative migration strategies (e.g., injustice and conflict) can trigger a relationship to move to a higher or lower stage, respectively.

The second category of studies in this group departs from the tradition of considering relationship trajectories as a whole (i.e., from initiation to termination) and focuses on smaller elements of these trajectories, namely, relationship trajectories and trends. In their efforts to develop a theory of relationship dynamics, Palmatier et al. (2013) argued that while it is essential to measure both the relationship level (e.g., quality) and slope (i.e., direction), slope represents the more dynamic aspect of a relationship. They found that dynamic elements were “more critical than the static level for predicting future behaviors and performance” (p. 26). This finding accords with research in relationship psychology that explains how parties evaluate relationship status based on recent relationship trends regardless of a history of fluctuation (Karney and Frye 2002). Another study (Narayandas and Rangan 2004) found that relationship development is more complicated than the consensus discussed earlier, partly because (1) variables such as trust were working between individuals, while other variables, such as commitment, materialized only at the organizational level, and (2) relationships usually commence with characteristics, such as power imbalances, that affect their subsequent choice of governance mechanisms. This finding is similar to the proposition advanced by the liability of adolescence thesis that BSRs start with an initial endowment of stocks such as trust and goodwill (Fichman and Levinthal 1991; Hoetker et al. 2007; Levinthal and Fichman 1988). The honeymoon period provided by this initial endowment of goodwill is a relationship trend of sorts that guards against premature termination even in the presence of early disappointing outcomes (Fichman and Levinthal 1991; Levinthal and Fichman 1988).

Two articles (Autry and Golicic 2010; Bell et al. 2009) have proposed the emergence of relationships’ initial conditions through spirals. Spirals and loops are indications that a relationship will become path dependent based on its previous choices, meaning that involved parties might “follow a routine even when there is substantial evidence that this routine is suboptimal” (Chassang 2010, p. 460). Bell et al. (2009) proposed the existence of a directional asymmetry between transactions over time, where the choice of governance mechanism may influence the future choice of governance mechanisms between the same parties. Autry and Golicic (2010) found some support for this claim by showing a cyclical link between relationship strength and relationship performance that can affect the initiation of future potential relationships with the same party.

Relationship fluctuations

Fluctuations are aspects of a relationship’s trajectory (often the result of specific incidents such as positive experiences, crises, conflicts, or opportunistic behaviors) that can be considered anomalies compared with the uninterrupted trajectory of the same relationship. Research focusing on relationship fluctuations has been concerned with three questions: (1) the temporal variables that influence relationship resolution and maintenance processes, (2) the timing of an incident and how it affects the subsequent relationship trend, and (3) the cumulative effect of recurring similar incidents.

Researchers have investigated how parties involved in a relationship react to or manage negative incidents and how time influences relationship resolution and maintenance processes. The goal has not been to understand whether organizations learn from these experiences—although this is likely to be the case—but, rather, to consider what organizations do before or during the fluctuation period. Some research has shown that temporal variables (e.g., a manager’s relationship tenure), as well as the history of interfirm relationships, can affect the decision of a damaged party to invest in relationship repair (Johnson and Sohi 2016). While a positive response (e.g., compromising or problem-solving strategies) might result in a concession on the part of the wrongdoer, an aggressive response might have adverse implications, including relationship termination. This temporal view is limited to the extent that it only examines the factors involved with the repair and does not speak to the change in an interorganizational relationship as a consequence of the repair process.

Grewal et al. (2007) explored the five-phase process through which parties choose their response to relationship fluctuations. They found that where information was scarce, the speed of response was slowed, leading parties to go through some phases several times before choosing a response to a crisis. The speed of response accelerated when managers were either (1) vigilant enough to predict a crisis or (2) under pressure to resolve a crisis quickly.

An alternative approach to managing relationships in the aftermath of negative behavior is to consider how temporal variables (such as speed of enforcement) might prevent negative behaviors from occurring in the first place. For example, Antia et al. (2006) found that in combination, the severity of punishment, the detectability of a negative incident, and the speed of enforcement could deter negative incidents from occurring.

Other studies have focused on the timing of an incident and how it affects the subsequent relationship trend (i.e., why incidents happen and how to prevent them from happening at particular times). More specifically, they have investigated what happens if a fluctuation occurs at the beginning of a relationship (i.e., no shadow of the past) versus later in a relationship and what can happen if a fluctuation occurs later in a relationship when there is a low expectation of future interaction (i.e., shadow of the future). While the reputation of the parties involved in an exchange (Blumberg 2001) can prevent them from acting opportunistically, there is no consensus on other temporal variables, such as potential future interactions, with regard to whether such variables can deter opportunism on their own (Rokkan et al. 2003) or whether they are effective only in the presence of positive reputation (Blumberg 2001). This difference can be attributed to the research context. Blumberg (2001) investigates a more general condition where parties try to immunize themselves against future opportunism by introducing contingency measures in their contracts, whereas Rokkan et al. (2003) study a context in which there is a high probability of opportunism due to the existence of transaction-specific investments. Rokkan et al. (2003) further argue that these investments in the presence of high levels of relationship extendedness will create a bonding effect in a relationship.

Other research has supported the effect of the timing of a positive or negative fluctuation on the decision to litigate a relationship (Bolton et al. 2006; Lumineau and Oxley 2012). For example, Lumineau and Oxley (2012) found an alignment between relationship characteristics at the time a crisis occurs and the likelihood of litigation in French BSRs. As relationships change over time, parties learn how to cooperate and develop expectations about the potential of their relationship. They showed that the norm of cooperation will increase the tolerance for adverse behaviors, while in the absence of cooperation, the probability of litigation increases with the history of interaction. The results of a more recent study in the U.S., however, speak to the narrowing of the zone of indifference due to the evolution of relational expectations, and show that negative relational events have the greatest effects on the relationship velocity in more developed relationships when relational expectations are high; the reverse is true for positive relational events (Harmeling et al. 2015). The difference between these studies might ultimately be due to cultural differences, however. Compared to their American counterparts, French managers are typically more risk averse, rely on bureaucratic authority (Hofstede 1991), and are under the influence of peer pressure (Burt et al. 2000), which can affect their decision making when faced with adverse behavior in their relationships. The longer a cooperative relationship exists, the more embedded the relationship will be, and ultimately, the high cost of bureaucratic procedures and the risk of an uncertain future might create a higher level of tolerance for such negative behaviors.

Another set of research studies has examined the cumulative effect of recurring similar incidents. These studies have demonstrated that one party’s perception of a history of conflict decreases its perception of the other party’s commitment to the relationship (Anderson and Weitz 1992). Therefore, it is less surprising that in socialization activities, a firm with a history of conflict will diminish its communication efforts with its counterparty (Van de Vijver et al. 2011). More recently, Seggie et al. (2013) have shown that the recurrence of negative incidents increases transaction costs at a positive rate.

Implications for theory and future relationship dynamics research

Our review has revealed four central themes in the dynamics of business-to-business relationships, each of which is composed of different theoretical underpinnings and mechanisms. We suggest that there is strength in this plurality, as it allows us to see existing problems through multiple lenses. New approaches to tackling old problems are the payoff from maintaining this plurality which we demonstrate by applying our themes to the two BSR research domains highlighted in the introduction.Footnote 5 Our first area of application is the relatively nascent field of BSR relationship transgression and repair. The second—the performance implications of relational versus formal governance choices—while more established has a history of equivocal evidence and sustained debate. While there are any number of BSR research questions that we might have considered, by focusing on only two, we balance focused application with brevity. We provide a brief summary of how these problems have been approached and identify some key questions in each that remain to be answered. We then demonstrate how each of our themes can cast an existing problem in a new light while also providing the foundation for resolving the problem. We offer these questions and potential answers as both theoretical implications and guidance for future research (see Table 2).

Relationship transgression and repair

The emerging literature on relationship transgression and repair considers how critical incidents affect relationship strength and the nature of the efforts by one or both parties to “return the relationship to a positive state” (Dirks et al. 2009, p.69). Despite being an important topic, our knowledge of relationship repair is limited to only a few studies, with most of them being static in design (Dirks et al. 2009). However, repair is a process that lends itself to dynamic theorizing, and therefore, we consider it an appropriate research topic against which we might demonstrate the theory-building potential of the four themes. Furthermore, by applying our dynamic themes to this topic, we respond to the general call by researchers in relationship repair to provide answers to questions about the role of transgression severity and subsequent effects on “attributions and willingness to forgive and reconcile” (Tomlinson and Mayer 2009, p.101).

Relationship fluctuations and repair

Transgressions represent extreme departures from relationship standards and norms as well as a threat to relationship continuity due to increases in uncertainty. They are transformational relationship events (Harmeling et al. 2015) that “trigger a reinterpretation of what the relationship means” to the aggrieved party (Graham 1997, p. 351). A standard assumption is that with greater uncertainty, there will be a reduced willingness to repair the relationship; the damaged party becomes less sure about its partner’s future actions (Mostafa et al. 2014). However, relationship repair decisions may not be so straightforward. Recent fluctuations in the relationship trajectory are likely to affect the decision to repair and the degree of commitment to the process.

A significant relationship transgression following recent, steady declines in relationship quality serves to confirm the recent experiences of the affected partner. The declining trajectory is yet another piece of evidence that influences the aggrieved partner’s willingness to invest in repair. An awareness of a history of minor failings means that the inevitable transgression simply confirms the character of the wrongdoer and the wrongdoer’s capacity to do similar damage in the future (Anderson and Weitz 1992; Kim et al. 2004). This notion is consistent with an attribution theory perspective in which poor performance tends to be attributed to an external agency (i.e., the partner) (Folkes and Kotsos 1986). A recent positive relationship trajectory, on the other hand, is more likely to be attributed to the aggrieved partner (i.e., “we made an astute choice of partners”). Thus, a significant transgression by the partner will be framed as a “temporary aberration” and an exception to the recent experience of cordial and productive relations. There may be a greater appetite to invest in relationship repair and the development of contingencies to prevent further similar transgressions from occurring. A recent trajectory of combined highs and lows may lead to mixed attributions and thus have unpredictable implications for willingness to repair. Nonetheless, integrating recent relationship fluctuations into models of relationship repair will help researchers understand the likelihood of parties committing to repair.

Relationship continuity and repair

As with understanding the influence of a relationship’s recent history and any inherent fluctuations therein, understanding the relationship’s intended expected horizon—its shadow of the future (Heide and Miner 1992)—may also influence the effectiveness of various repair strategies. There is a stream of research focused on how relationships might be repaired following a violation (e.g., Kim et al. 2004; Schweitzer et al. 2006), but there is relatively little work on understanding the contexts in which some strategies are more effective than others. Potentially, an aggrieved party’s expectation of relationship continuity could lead to a more positive reception of proactive (i.e., preventative) repair strategies than reactive (i.e., corrective) strategies (Jones et al. 2011). An aggrieved party who anticipates a long-term relationship with a partner will be more appreciative of measures that forestall disruptions in the future than those that make good on violation in the moment. The latter, however, might be more important for a partner who does not anticipate a longer relationship and simply seeks recompense before exit.

Relationship stages and trajectories and repair

One argument in life-cycle models of business relationships is that interdependencies increase from start-up, through expansion and growth, and into maturity (Dwyer et al. 1987). Therefore, damaged relationships at mature stages have a long history of information sharing and familiarity on which to draw in seeking resolution. Mature relationships will also have agreed-upon modes of communication and dispute resolution protocols on which to draw (Zhang et al. 2016). In summary, the motivation to repair is likely to be stronger at these later relationship phases. However, there is also evidence to suggest that early-stage relationships—especially those with high potential—begin with relatively low expectations (Harmeling et al. 2015). Turning around a damaged relationship to a more functional state will be easier than at later stages, where mutual expectations are likely to be higher (and tolerance for variability lower). At a minimum, these insights suggest that relationship transgressions cannot be understood in an absolute sense; the definition of a relationship transgression will always be framed by, among other things, the stage of the relationship at which the transgression occurred.

Relationship learning and repair

The motivation to repair a relationship following a transgression may be affected by the remedies available to the aggrieved party to achieve some resolution and to protect itself from similar transgressions in the future. Therefore, relationship repair is likely to depend not so much on the degree of reliance on formal contracts but on the sophistication of the formal contracts themselves. As relationships age and parties gain more information about each other, they also learn how to write better formal control mechanisms (Li et al. 2010) by including more relevant contingencies in the contract that align with the needs of each party (Argyres et al. 2007). Taking a learning perspective to the writing and use of formal contracts might help explain the point at which a contract changes from a document designed to prevent asset appropriation to a foundation from which cooperation, coordination, and repair proceed (Gulati 1995).

Relational versus formal governance

In this section, we investigate the implications of the four themes for a business relationship problem that has been the focus of researchers for some time—the performance implications of relational versus formal governance solutions. These governance mechanisms are understood based on their different features (e.g., reliance on norms and mutual trust versus reliance on formal and written contracts), the different contexts in which they might be relevant (e.g., different relationship lengths, contracting experiences, environmental uncertainty), and whether they act as substitutes for one another or as complements (Cao and Lumineau 2015). We contend that our themes might offer some answers to some of these questions.

Relationship fluctuations and relational versus formal governance

The notion of governance mechanism complementarity has attracted the attention of relationship researchers for some time. Earlier work that claimed that relational governance substitutes for formal arrangements (e.g., Dyer and Singh 1998; Macaulay 1963) was upended by later findings demonstrating the complementarity between them (e.g., Poppo and Zenger 2002; Wuyts and Geyskens 2005). More recent work has advocated both complementarity and substitutability, depending on the primary purpose of the contract (Mellewigt et al. 2007). We suggest that the effect of governance choices might iterate between complementarity and substitutability as a result of relationship fluctuations. For example, a recent positive trajectory might help relationship parties frame the invocation of contractual terms (e.g., to settle a dispute) as a “backstop” in an otherwise trusting and mutually adaptive relationship. Framed by a recent relationship decline, on the other hand, falling back on contractual remedies may confirm partners’ perceptions that the relationship is fragile, further undermining trust.

Relationship continuity and relational versus formal governance

Research on relationship continuity might be able to help answer questions about the appropriate contexts in which to deploy relational versus formal governance. Consider, for example, the notion of environmental dynamism, which has been found to have both a negative (e.g., Oh et al. 1992) and positive relationship (Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven 1996) with the use of relational governance. While some scholars have addressed this question through the (dynamic) lens of relationship learning (e.g., Joshi and Campbell 2003), we also see the potential for relationship continuity to explain the direction of this relationship. A long shadow of the future implies a willingness to adapt to the other partner’s needs despite changing circumstances (Lusch and Brown 1996; Ren et al. 2010). Therefore, environmental dynamism might be seen as an opportunity to jointly adapt to market opportunities rather than as a problem to be eliminated, and consequently, it will be positively associated with relational governance. When relationship continuity is relatively short, on the other hand, the specter of opportunism looms large (Poppo et al. 2008), especially in an ever-changing environment. This threat of opportunism, we suggest, will push relationship partners toward formal governance mechanisms that provide clear remedies for an aggrieved partner.

Relationship stages and trajectories and relational versus formal governance

The relative impact of formal versus relational governance or the feasibility of implementing a governance choice might also be a function of the relationship stage; this question was foreshadowed by Cao and Lumineau (2015, p. 33), who asked, “how does the phase of cooperation moderate the contracts-relational governance interplay?” Moon et al. (2004) suggest that the origin of a firm’s development pathway matters, as it may mean that it is easier to move a social system in one direction than to move it in another. In other words, there are likely to be path dependencies based on the relationship stage. For example, the setup costs of relational governance will likely exceed the setup costs of formal governance due to their higher social requirements (Soda et al. 2004). However, it will be far easier to transition from relational governance to a formally governed relationship due to the inherent adaptive qualities of relational governance (Bell et al. 2009). On the other hand, formal governance—and the structures upon which it relies—is often subject to inertia (Hannan and Freeman 1984). The stability promoted by formal governance may become a liability when a firm looks to reset its relationship governance arrangements to take a more relational tone. By incorporating the relationship stage or trajectory into studies of governance choices and their impact, researchers are likely to gain a far more nuanced understanding of relationship performance.

Relationship learning and relational versus formal governance

As noted earlier, relationship learning has been used to reconcile the equivocal evidence regarding the relationship between environmental uncertainty and the use of relational governance (Joshi and Campbell 2003). We also see its potential for explaining how complementarity in governance mechanisms emerges. Learning might potentially operate in two important ways. First, it might help partners gain a mutual understanding of when “to use the contract and when [to] renegotiate” (Cao and Lumineau 2015, p. 33). Therefore, a relationship characterized by high levels of learning will see reliance on contractual terms limited to a smaller set of contingencies and upon mutual agreement. Second, learning is likely to influence the ongoing refinement of the contract to include the possibility of “bilateral adjustments [that] facilitate the evolution of highly cooperative exchange relations” (Poppo and Zenger 2002, p. 713). In other words, deeper familiarity with a partner will help determine where flexibility and adaptability—two foundations of relational exchange—can be allowed for within the contract. The contract can evolve by adding clauses “aimed at better incentive alignment, dispute prevention, and dispute resolution” (Mayer and Argyres 2004, p. 403). Thus, contracts will evolve to focus less on detailed task description clauses and more on developing contingency planning clauses to control for transaction characteristics.

Managerial implications

The themes identified in our review have a number of interesting implications for managers, whether in for-profit, government, or third sector organizations. While we have used the language of “buyer” and “supplier” throughout the paper, the ideas have general applicability in any context in which a firm must manage a relationship with an external stakeholder for whom value is created or from whom value is derived. We offer three managerial implications derived from our themes.

First, by identifying the drivers of relationship continuity (e.g., trust and transaction-specific assets), our findings provide managers with a comprehensive set of tools to build a long-term relationship. However, we urge caution regarding the positive and negative self-referential effects of the expectation of continuity. Managers should rely on the positive history of their relationship only when they are confident about their counterparty’s long-term orientation toward the relationship (e.g., Poppo et al. 2008). Otherwise, they make themselves vulnerable to potential opportunistic behaviors. Organizations learn to use relational mechanisms over time (e.g., Mayer and Argyres 2004); however, if the relationship is without a viable shadow of the future, relying on relational mechanisms such as trust can be foolhardy. Managers should monitor partners for their expectations of an ongoing relationship and devise formal contracts as safeguards where this future orientation is difficult to divine.

Second, in addition to being a governance mechanism and playing a role in relationship management, contracts can serve as a “relationship memory updating tool” to compensate for the lack of knowledge spillovers across relationships and the fact that learning about potential contingencies is “almost entirely internal to the contractual relationship” (Mayer and Argyres 2004, p. 404). Managers might actively track and record contract modifications over time to learn how new relationships might be more quickly strengthened. Thus, contracts themselves might be used as a form of organizational memory, an archive of sorts to which managers might return to help fast-track the development of new relationships.

Third, as a company continues to work with the same party, managers should be more vigilant with respect to the initial conditions of their relationship. These conditions emerge through spirals, where the characteristics of the previous contractual relationship will influence the future relationship with the same party (Bell et al. 2009). Assuming that success in a relationship motivates the signing of a new contract with the same organization, this process should lead to positive initial conditions, thus inoculating the relationship against early termination (e.g., Fichman and Levinthal 1991). Managers should account for these conditions when searching for a potential partner, as these initial conditions can act as self-enforcing governance mechanisms in the early stages of a relationship—something that is missing in industries where, for example, the supplier search process is conducted mainly through a tender process.

Conclusion

Few scholars would dispute the profound role of dynamics in BSRs. However, this topic remains relatively under-researched not only in the marketing literature but also in the management literature as well as other cognate disciplines. Here, we have reviewed the literature in leading marketing, management, economics, accounting, and sociology journals to highlight current debates regarding the state of the art in BSR dynamics. We have discussed the contributions of our themes as a dynamic lens that can be applied to static research questions and outlined some directions for future research. Although the directions we propose are focused on a subset of BSR research areas, our hope is that they will stimulate new ideas and new theory in this critical field of inquiry.

Notes

We exclude other forms of interorganizational relationships, such as joint ventures and alliances. Joint ventures often involve mutual ownership and exclusivity arrangements (Houston and Johnson 2000; Parmigiani and Rivera-Santos 2011) and are considered governance mechanisms in their own right (Heide 1994). Further, alliances are often so broadly defined “that nearly any [interorganizational relationship] could be considered an alliance” (e.g., Parmigiani and Rivera-Santos 2011, p. 1116). While these forms of interorganizational relationship are no less subject to relationship dynamics, by omitting these from our review we avoid confounds between underlying dynamic mechanisms and the peculiarities of these governance solutions.

Dynamic, relationship, U-shape, interorganizational, evolve, interfirm, courtship, honeymoon, marriage, life-cycle, cycle, B2B, buyer, supplier, shadow of the past, shadow of the future, period, episode, time, duration, history, temporal, length, speed, routine, slope, sequence, stage, phase, longitudinal, case study, interview, qualitative, ethnography, grounded theory, inertia, path dependence, population ecology, organizational ecology, economic sociology, life cycle theory, trajectory, process, and change.

Academy of Management Journal, Academy of Management Review, Accounting, Organizations & Society, Administrative Science Quarterly, American Economic Review, Human Relations, Information Systems Research, Journal of International Business Studies, Journal of Management, Journal of Management Studies, Journal of Marketing, Journal of Marketing Research, Journal of Operations Management, Journal of Political Economy, Management Science, Marketing Science, MIS Quarterly, Operations Research, Organization Studies, Production & Operations Management, Quarterly Journal of Economics, Research Policy, Review of Economic Studies, Strategic Management Journal, International Journal of Research In Marketing, and Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science.

American Journal of Sociology, American Sociological Review, Annual Review of Sociology, Journal of Retailing, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Academy of Management Annals, Industrial & Corporate Change, Strategic Organization, Supply Chain Management, Journal of Supply Chain Management, and Journal of Law & Economics.

An alternative approach was to try combining these themes into a “grand theory” of relationship dynamics. We considered such an endeavor to be less valuable for a number of reasons. First, there is a significant degree of theoretical and conceptual incommensurability between the themes in our review. This incommensurability is a function of the large number of disciplines surveyed and the varied nature of focal research questions. Second, as a direct consequence of this theoretical plurality, aggregation into a general model would require such a high level of abstraction as to be relatively meaningless for researchers seeking specific direction in regard to model design.

References

Achrol, R. S., Reve, T., & Stern, L. W. (1983). The environment of marketing channel dyads: A framework for comparative nalysis. Journal of Marketing, 47(4), 55–67.

Amit, J. (2016). Learning by hiring and change to organizational knowledge: Countering obsolescence as organizations age. Strategic Management Journal, 37(8), 1667–1687.

Anderson, E., & Weitz B. (1989). Determinants of continuity in conventional industrial channel dyads. Marketing Science, 8 (4), 310–323.

Anderson, E., & Weitz B. (1992). The use of pledges to build and sustain commitment in distribution channels. Journal of Marketing Research, 29 (1), 18–34.

Antia, K. D., Bergen, M. E., Duta, S., & Fisher, R. J. (2006). How does enforcement deter gray market incidence?. Journal of Marketing, 70 (1), 92–106.

Argyres, N. S., Bercovitz, J., & Mayer, K. J. (2007). Complementarity and evolution of contractual provisions: An empirical study of IT services contracts. Organization Science, 18 (1), 3–19.

Ariño, A., Reuer, J. J., Mayer, K. J., & Jané, J. (2014). Contracts, negotiation, and learning: An examination of termination provisions. Journal of Management Studies, 51 (3), 379–405.

Autry, C. W., & Golicic, S. L. (2010). Evaluating buyer–supplier relationship–performance spirals: A longitudinal study. Journal of Operations Management, 28 (2), 87–100.

Barringer, B. R., & Harrison, J. S. (2000). Walking a tightrope: Creating value through interorganizational relationships. Journal of Management, 26(3), 367–403.

Bell, S. J., Whitwell, G. J., & Lukas, B. A. (2002). Schools of thought in organizational learning. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30(1), 70–86.

Bell, S. J., Tracey P., & Heide, J. B. (2009). The organization of regional clusters. Academy of Management Review, 34 (4), 623–642.

Blumberg, B. F. (2001). Cooperation contracts between embedded firms. Organization Studies, 22 (5), 825–852.

Bolton, R. N., Lemon, K. N., & Bramlett, M. D. (2006). The effect of service experiences over time on a supplier’s retention of business customers. Management Science, 52 (12), 1811–1823.

Brattström, A., Faems, D., & Mähring, M. (2019). From trust convergence to trust divergence: Trust development in conflictual interorganizational relationships. Organization Studies, 40(11), 1685–1711.

Briner, R. B., Denyer, D., & Rousseau, D. M. (2009). Evidence-based management: Concept cleanup time? Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(4), 19–32.

Burt, R. S., Hogarth, R. M., & Michaud, C. (2000). The social Capital of French and American Managers. Organization Science, 11(2), 123–147.

Cao, Z. & Lumineau, F. (2015). Revisiting the interplay between contractual and relational governance: A qualitative and meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Operations Management, 33, 15–42.

Carson, S. J., & Ghosh, M. (2019). An integrated power and efficiency model of Contractual Channel governance: Theory and empirical evidence. Journal of Marketing, 83(4), 101–120.

Chassang, S. (2010). Building routines: Learning, cooperation, and the dynamics of incomplete relational contracts. American Economic Review, 100(1), 448–465.

Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. L. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc..

Dabholkar, P. A., Johnston, W. J., & Cathey, A. S. (1994). The dynamics of long-term business-to-business exchange relationships. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science (2), 130.

Dacin, M. T., Munir, K., & Tracey, P. (2010). Formal dining at Cambridge colleges: Linking ritual performance and institutional maintenance. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1393–1418.

Das, T. K., & Teng, B. S. (2002). The dynamics of alliance conditions in the alliance development process. Journal of Management Studies, 39(5), 725–746.

Dekker, H. C., & Van den Abbeele, A. (2010). Organizational learning and interfirm control: The effects of partner search and prior exchange experiences. Organization Science, 21 (6), 1233–1250.

Dirks, K. T., Lewicki, R. J., & Zaheer, A. (2009). Repairing relationships within and between organizations: Building a conceptual foundation. Academy of Management Review, 34(1), 68–84.

Dwyer, F. R., Schurr, P. H., & Oh, S. (1987). Developing buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 51 (2), 11–27.

Dyer, J. H. (1997). Effective interfirm collaboration: How firms minimize transaction costs and maximize transaction value. Strategic Management Journal, 18 (7), 535–556.

Dyer, J. H., & Nobeoka, K. (2000). Creating and managing a high-performance knowledge-sharing network: The Toyota case. Strategic Management Journal, 21(3), 345–367.

Dyer, J. H., & Singh, H. (1998). The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 660–679.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Schoonhoven, C. B. (1996). Resource-based view of strategic alliance formation: Strategic and social effects in entrepreneurial firms. Organization Science, 7(2), 136–150.

Fichman, M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1991). Honeymoons and the liability of adolescence: A new perspective on duration dependence in social and organizational relationships. Academy of Management Review, 16 (2), 442–468.

Flint, D. J., Woodruff, R. B., & Fisher Gardial, S. (2002). Exploring the phenomenon of customers’ desired value change in a business-to-business context. Journal of Marketing, 66 (4), 102–117.

Folkes, V. S., & Kotsos, B. (1986). Buyers' and sellers' explanations for product failure: Who done it? Journal of Marketing, 50(2), 74–80.

Ford, D., Gadde, L.-E., Håkansson, H., Lundgren, A., Shenota, I., Turnbull, P., & Wilson, D. (1998). Managing business relationships. Chichester: Wiley.

Frazier, G. L. (1983). Interorganizational exchange behavior in marketing channels: A broadened perspective. Journal of Marketing, 47 (4), 68–78.

Ganesan, S. (1993). Negotiation strategies and the nature of channel relationships. Journal of Marketing Research, 30 (2), 183–203.

Ganesan, S. (1994). Determinants of long-term orientation in buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 58 (2), 1, 19.

Gomes, E., Barnes, B. R., & Mahmood, T. (2016). A 22 year review of strategic alliance research in the leading management journals. International Business Review, 25(1), 15–27.

Graham, E. E. (1997). Turning points and commitment in post-divorce relationships. Communications Monographs, 64(4), 350–368.

Grayson, K., & Ambler, T. (1999). The dark side of long-term relationships in marketing services. Journal of Marketing Research, 36 (1), 132–141.

Grewal, R., Johnson, J. L., & Sarker, S. (2007). Crises in business markets: Implications for interfirm linkages. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35 (3), 398–416.

Gulati, R. (1995). Social structure and alliance formation patterns: A longitudinal analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(4), 619–652.

Hamilton, R. W., Schlosser, A., & Chen, Y.-J. (2017). Who's driving this conversation? Systematic biases in the content of online consumer discussions. Journal of Marketing Research, 54(4), 540–555.

Hannan, M. T., & Freeman, J. (1984). Structural inertia and organizational change. American Sociological Review, 49(2), 149–164.

Harmeling, C. M., Palmatier, R. W., Houston, M. B., Arnold, M. J., & Samaha S. A. (2015). Transformational relationship events. Journal of Marketing, 79 (5), 39–62.

Heide, J. B. (1994). Interorganizational governance in marketing channels. Journal of Marketing, 58 (1), 71–85.

Heide, J. B., & John, G. (1992). Do norms matter in marketing relationships? Journal of Marketing, 56(2), 32–44.

Heide, J. B., & Miner, A. S. (1992). The shadow of the future: Effects of anticipated interaction and frequency of contact on buyer-seller cooperation. Academy of Management Journal, 35 (2), 265–291.

Hoetker, G., Swaminathan, A., & Mitchell, W. (2007). Modularity and the impact of buyer–supplier relationships on the survival of suppliers. Management Science, 53 (2), 178–191.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Empirical models of cultural differences. In N. Bleichrodt & P. J. D. Drenth (Eds.), Contemporary issues in cross-cultural psychology (pp. 4–20). Swets & Zeitlinger Publishers.

Hollmann, T., Jarvis, C., & Bitner, M. (2015). Reaching the breaking point: A dynamic process theory of business-to-business customer defection. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43 (2), 257–278.

Hoppner, J. J., & Griffith, D. A. (2011). The role of reciprocity in clarifying the performance payoff of relational behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 48 (5), 920–928.

Houston, M. B., & Johnson, S. A. (2000). Buyer-supplier contracts versus joint ventures: Determinants and consequences of transaction structure. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(1), 1–15.

Huston, T. L., Houts, R. M., Caughlin, J. P., Smith, S. E., & George, L. J. (2001). The connubial crucible: Newlywed years as predictors of marital delight, distress, and divorce. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 80(2), 237–252.

Im, G., & Rai, A. (2008). Knowledge sharing ambidexterity in long-term interorganizational relationships. Management Science, 54 (7), 1281–1296.

Inkpen, A. C., & Currall, S. C. (2004). The coevolution of trust, control, and learning in joint ventures. Organization Science, 15(5), 586–599.

Jap, S. D., & Anderson, E. (2007). Testing a life-cycle theory of cooperative interorganizational relationships: Movement across stages and performance. Management Science, 53 (2), 260–275.

Jap, S. D., & Ganesan, S. (2000). Control mechanisms and the relationship life cycle: Implications for safeguarding specific investments and developing commitment. Journal of Marketing Research, 37 (2), 227–245.

Johnson, J. S., & Sohi, R. S. (2016). Understanding and resolving major contractual breaches in buyer-seller relationships: A grounded theory approach. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44 (2), 185–205.

Jones, T., Dacin, P. A., & Taylor, S. F. (2011). Relational damage and relationship repair: A new look at transgressions in service relationships. Journal of Service Research, 14(3), 318–339.

Joshi, A. W., & Campbell, A. J. (2003). Effect of environmental dynamism on relational governance in manufacturer-supplier relationships: A contingency framework and an empirical test. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31(2), 176–188.

Karney, B. R., & Bradbury, T. N. (1995). The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, methods, and research. Psychological Bulletin, 118(1), 3–34.

Karney, B. R., & Frye, N. E. (2002). ‘But we’ve been getting better lately’: Comparing prospective and retrospective views of relationship development. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 82(2), 222–238.

Kaufmann, L., & Carter, C. R. (2006). International supply relationships and non-financial performance—A comparison of U.S. and German practices. Journal of Operations Management, 24 (5), 653–675.

Kim, P. H., Ferrin, D. L., Cooper, C. D., & Dirks, K. T. (2004). Removing the shadow of suspicion: The effects of apology versus denial for repairing competence- vs. integrity-based trust violations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(1), 104–118.

Kim, P. H., Dirks, K. T., & Cooper, C. D. (2009). The repair of trust: A dynamic bilateral perspective and multilevel conceptualization. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 401–422.

Kogut, B. (1988). Joint ventures: Theoretical and empirical perspectives. Strategic Management Journal, 9(4), 319–332.

Kotabe, M., Martin, X., & Domoto, H. (2003). Gaining from vertical partnerships: Knowledge transfer, relationship duration and supplier performance improvement in the U.S. and Japanese automotive industries. Strategic Management Journal, 24 (4), 293–316.

Krause, D. R. (1999). The antecedents of buying firms’ effort to improve suppliers. Journal of Operations Management, 17 (2), 205–224.

Lee, D. J., Sirgy, M. J., Brown, J. R., & Bird, M. M. (2004). Importers’ benevolence toward their foreign export suppliers. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32 (1), 32–48.

Levinthal, D. A., & Fichman, M. (1988). Dynamics of interorganizational attachments: Auditor-client relationships. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33 (3), 345–369.

Li, Y., Xie, E., Teo, H. H., & Peng, M. W. (2010). Formal control and social control in domestic and international buyer–supplier relationships. Journal of Operations Management, 28 (4), 333–344.

Lincoln, Y, S., & Guba, E, G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage

Lipparini, A., Lorenzoni, G., & Ferriani, S. (2014). From core to periphery and back: A study on the deliberate shaping of knowledge flows in interfirm dyads and networks. Strategic Management Journal, 35 (4), 578–595.

Lui, S. S. (2009). The roles of competence trust, formal contract, and time horizon in interorganizational learning. Organization Studies, 30 (4), 333–353.

Lumineau, F., & Oxley, J. E. (2012). Let’s work it out (or we’ll see you in court): Litigation and private dispute resolution in vertical exchange relationships. Organization Science, 23 (3), 820–834.

Lusch, R. F., & Brown, J. R. (1996). Interdependency, contracting, and relational behavior in marketing channels. Journal of Marketing, 60 (4), 19–38.

Macaulay, S. (1963). Non-contractual relations in business: A preliminary study. American Sociological Review, 28(1), 55–67.

March, J. G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 71–87.

Mayer, K. J., & Argyres, N. S. (2004). Learning to contract: Evidence from the personal computer industry. Organization Science, 15 (4), 394–410.

Mellewigt, T., Madhok, A., & Weibel, A. (2007). Trust and formal contracts in interorganizational relationships—Substitutes and complements. Managerial and Decision Economics, 28(8), 833–847.

Miner, A. S., Bassoff, P., & Moorman, C. (2001). Organizational improvisation and learning: A field study. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(2), 304–337.

Mir, S., Aloysius, J. A., & Eckerd, S. (2017). Understanding supplier switching behavior: The role of psychological contracts in a competitive setting. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 53 (3), 3–18.

Moon, H., Hollenbeck, J. R., Humphrey, S. E., Ilgen, D. R., West, B., Ellis, A. P., & Porter, C. O. (2004). Asymmetric adaptability: Dynamic team structures as one-way streets. Academy of Management Journal, 47(5), 681–695.

Moorman, C., Zaltman, G., & Deshpande, R. (1992). Relationships between providers and users of market research: The dynamics of trust within and between organizations. Journal of Marketing Research, 29(3), 314–328.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38.

Mostafa, R., Lages, C. R., & Sääksjärvi, M. (2014). The CURE scale: A multidimensional measure of service recovery strategy. Journal of Services Marketing, 28(4), 300–310.

Narayandas, D., & Rangan, V. K. (2004). Building and sustaining buyer-seller relationships in mature industrial markets. Journal of Marketing, 68 (3), 63–77.

Niesten, E., & Jolink, A. (2015). The impact of alliance management capabilities on alliance attributes and performance: A literature review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 17(1), 69–100.

Nippa, M., & Reuer, J. J. (2019). On the future of international joint venture research. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(4), 555–597.