Abstract

Health care costs are an important consideration in the decision of hysterectomy routes and robotic surgery is often critiqued for its high cost. We sought to compare the cost of robotic-assisted hysterectomies performed after initial acquisition of the robotic surgical system to cases performed after 5 years of experience. The first 20 patients at a community teaching hospital who underwent robotic-assisted hysterectomy for endometrial cancer by a single gynecologic oncology surgeon were designated Group 1 and 20 patients undergoing robotic hysterectomies 5 years later for the same indication were designated Group 2. Direct hospital costs were divided into operative and non-operative costs. Mean operating room cost and cost of anesthesia per minute for Group 1 were adjusted to Group 2 mean costs. Supply costs were adjusted using the 2015 Consumer Price Index. Baseline characteristics of the groups were comparable. After 5 years of experience, there was a 15.5% [95% CI (−$2865, −$407), p = 0.01] reduction in mean total costs (Group 1 = $10,543, Group 2 = $8907) and a 14.3% [95% CI (−$2378, −$390), p ≤ 0.01] reduction in mean operative costs (Group 1 = $9688, Group 2 = $8304). Significant reductions in procedure time, operating room time, operating room cost, and cost of anesthesia were seen from Group 1 to Group 2. There were no differences in mean non-operative costs, estimated blood loss, cost of supplies or surgeon cost. Experience with robotic-assisted hysterectomies is associated with reduction in costs, which is primarily a result of reduced operative times. This is an important factor when considering costs related to robotic surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The optimal approach to safely and efficiently perform hysterectomies has long been an area of debate. This controversy has become further complicated with the Food and Drug Administration approval of the da Vinci robot (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnvale, CA USA) in 2000 [1]. A primary criticism of robotic-assisted surgery is the high cost. However, robotic surgery continues to gain popularity in the field of gynecology [1] as evidenced by the eightfold increase in the number of robotic hysterectomies in the United States between 2008 and 2010 [2].

Because this technology is relatively new, most studies evaluating the cost of robotic-assisted surgery have been limited to cases performed within 3 years of acquiring the robot [3, 4], use of the first set number of consecutive cases performed [5], or do not quantify prior experience with this surgical method [6]. The literature suggests that increased surgical experience with total laparoscopic hysterectomies for endometrial cancer decreases the total operative time and improves surgical outcomes [7]. Further review of the literature shows that the greatest proportion of robotic hysterectomy costs is associated with time spent in the operating room [8]. Therefore, our study objective was to investigate if increased surgical experience with robotic hysterectomies over 5 years would be associated with a reduction in the cost of robotic surgery.

Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval by the LifeBridge Health Institutional Review Board committee (Baltimore, MD, USA), we conducted a retrospective cohort study at a community teaching hospital. The institutional medical records database was searched, and the first 20 consecutive laparoscopic robotic-assisted hysterectomies performed by a single surgeon for a diagnosis of endometrial cancer were identified (Group 1). This institution purchased the da Vinci surgical system in 2009, and these surgeries were performed from October 2009 to May 2010. The medical records database was then searched for the most recent consecutive laparoscopic robotic-assisted hysterectomies performed for a diagnosis of endometrial cancer (Group 2) completed from September 2014 to March 2015. Institutional board approval was obtained in March 2015 and the 20 consecutive cases prior to that date were reviewed.

Cost data were obtained from the institution’s finance department. Direct hospital costs were divided into operative costs and non-operative costs. Direct costs were defined as the institution’s actual cost of materials, labor, and expense. Operative costs were defined as all costs accrued in the operating room and included operating room time, cost of anesthesia, cost of surgical supplies, and surgeon cost. The surgeon cost was ascertained by the reimbursement rate for the specified procedure as determined by the Maryland State Health Services Cost Review Commission [9], which is a state-run organization that pre-sets mandates for service-specific rates for inpatient and outpatient hospital procedures uniformly across the state for all payers. This meant federally funded “Medicaid” patients and private insurance company patients were charged the same reimbursement rate if the same procedure codes were billed. Non-operative costs included room and board, medications, radiology, laboratory and pathology studies, and other accumulated costs during the hospitalization. Data for operative outcomes were obtained from operative notes, nursing documentation, pathology reports, and discharge summaries. Operating room time was defined as the time the patient entered the operating room until departure. Procedure time was defined as time of skin incision until the patient returned to the dorsal supine position, which are the definitions the institution set for start and stop time for all laparoscopic surgical procedures.

To account for cost differences between the time periods, mean cost outcomes for Group 1 were adjusted to the mean costs of Group 2. The mean cost for time in the operating room for Group 1 was $15.89 per minute, which was adjusted to $19.59 per minute, the mean cost of time in the operating room for Group 2. The mean cost of anesthesia for Group 1 was $0.94 per minute, which was adjusted to $1.34 per minute, the mean cost of anesthesia for Group 2. The cost of supplies was adjusted per the Consumer Price Index [10] difference from 2010 to 2015.

Student’s t test was used to compare characteristics and mean costs between groups. Pooled estimates were used when there was no significant difference in variances. Satterthwaite estimate was used for analysis in procedure time, cost of anesthesia, supplies cost, and surgeon cost since there was a significant difference in variances between groups. Statistical significance was defined as a p value of <0.05. All analyses were performed in SAS (version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The study group baseline characteristics are provided in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences in age, body-mass index (BMI), or uterine weight between the groups.

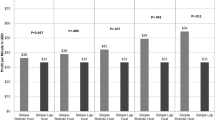

A detailed description and comparison of the costs for each group is provided in Table 2. Over 5 years, there was a $1636 (USD) reduction in mean total cost [95% CI (−$2865, −$407), p = 0.01] between Group 1 and Group 2 (Group 1 = $10,543, Group 2 = $8907) and a 14.3% or $1384 reduction in mean operative costs [95% CI (−$2378, −$390), p ≤ 0.01] between Group 1 and Group 2 (Group 1 = $9688, Group 2 = $8304). This translates to a 15.5% reduction in mean total costs and a 14.3% reduction in mean operative costs. There was a non-significant $252 reduction in mean non-operative costs [95% CI (−$651, $148), p = 0.20] between Group 1 and Group 2 (Group 1 = $855, Group 2 = $603).

When the operative cost components were analyzed, there was a significant reduction in mean operating room cost [−$727, 95% CI (−$1119, −$336), p < 0.01] over the 5-year period. Additionally, a statistically significant reduction in mean cost of anesthesia was demonstrated [−$47, 95% CI (−$75, −$20), p < 0.01] between Group 1 and Group 2. Cost of supplies and surgeon cost were similar for both groups. See Table 2.

Operative outcomes are reported in Table 3. There was a 25.3-min [95% CI (−44.6 min, −6.0 min), p = 0.01] reduction in mean procedure time and a 35.9-min [95% CI (−56.5 min, −15.1 min), p < 0.01] reduction in total operating room time observed over the 5-year period.

Estimated blood loss did not differ between the two groups. One case in Group 2 was converted to laparotomy due to a larger than expected uterus. No patient in either group experienced major medical complications (i.e. myocardial infarction, venous thromboembolism, sepsis, etc.) during their hospitalization.

Discussion

Health care-related costs are an important consideration in the implementation of both health care policy and clinical management decisions. We have demonstrated a significant reduction in the cost of robotic hysterectomies after 5 years of experience with robotic surgery. This reduction in total cost is attributable to reduced operative costs, which were primarily related to the decrease in operating room time. Over 50% of the reduction in operative costs was related to operating room cost and cost of anesthesia which are directly correlated with procedure time and operating room time. Total non-operative costs did not change significantly. Our study suggests that the costs of robotic surgery may be over-estimated if one only considers the cost related to the initial cases where the surgeon is less experienced.

Many studies have compared the cost of different routes of hysterectomy [3,4,5,6, 11] and proposed strategies of cost reduction [12]. Woelk et al. [4] compared cost differences among robotic, vaginal, and abdominal and found no significant cost difference between robotic and abdominal hysterectomy ($14,679 vs $15,588, p = 0.35). However, their study showed costs for robotic hysterectomies were based on cost data from the first 2 years after their acquisition of the robotic surgical system. Our study suggests the cost of robotic hysterectomies may decrease with experience and thus may become more cost effective than abdominal hysterectomies.

A primary strength of our study is that we obtained the hospital’s direct costs for each case and thus we did not have to depend on estimates and assumptions as is commonly required in cost-effectiveness studies. Furthermore, utilizing the institution’s direct costs in our analysis avoids the considerable variability associated with charges that occur between regions and institutions. The cases were all consecutive and performed by a single surgeon at the same community teaching institution for a single diagnosis. The purpose of this was to reduce the reduce risk of bias and control for potential confounders; however, we acknowledge that this limits the generalizability of our findings. Our study was also strengthened by the similar patient characteristics between the two study groups.

We recognize there are additional study limitations besides the generalizability of the findings. All retrospective cohort studies have inherent biases and potential confounders, despite our efforts to minimize them. Furthermore, supply costs were adjusted per the Consumer Price Index [10], a method meant to estimate general consumer product inflation, not necessarily inflation amongst medical supply cost. However, this is the best method available to adjust for inflation and is routinely used in health care research. It is difficult to predict the precise learning curve for robotic surgery and the number of cases that determine the learning curve have been reported anywhere from 20 to over 90 cases [13,14,15]. We recognize the relatively small sample size of 20 patients in each arm of our study; however, this was intentional to minimize the surgeon’s learning curve from affecting the study groups. Furthermore, we did not incorporate the cost of long-term outcomes such as readmissions, time until resumption of normal activity, or patient satisfaction. More studies are needed to determine precise economic and societal implications of robotic surgery.

Based on the findings of other studies that have shown operative times are reduced with surgeon experience [7] and that operative time is major component of cost [8], we believe the findings of our study to be credible. It is important that this type of study be performed in other health care systems and environments to determine the broader impact of surgeon and institution experience on the cost of robotic surgery. Future studies investigating strategies to reduce operative times are warranted since operative time has a major influence on costs associated with the surgery.

Robotic-assisted surgery remains in its formative years and further improvements in technology and greater understanding of the overall impact on healthcare are necessary. Our study demonstrates that with time and surgeon experience, a decrease in the cost of robotic-assisted hysterectomies can be expected in a community teaching institution. Strategies to reduce procedure time and time in the operating room are likely to be effective in reducing the overall cost of robotic surgery.

References

Yu HY, Friedlander DF, Patel S, Hu JC (2013) The current status of robotic oncologic surgery. CA Cancer J Clin 63:45–56

Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Tsui J et al (2013) Nationwide trends in the performance of inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 122:233–241

Desille-Gbaguidi H, Hebert T, Paternotte-Villemagne J, Gaborit C, Rush E, Body G (2013) Overall care cost comparison between robotic and laparoscopic surgery for endometrial and cervical cancer. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 17:348–352

Woelk J, Borah BJ, Trabuco EC, Heien HC, Gebhart JB (2014) Cost differences among robotic, vaginal, and abdominal hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 123:255–262

Sarlos D, Kots L, Stevanovi CN, Schaer G (2010) Robotic hysterectomy versus conventional laparoscopic hysterectomy: outcomes and cost analysis of a matched case–control study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 150:92–96

Wright K, Jonsdottir GM, Jorgensen S, Shah N, Einarsson JI (2012) Costs and outcomes of abdominal, vaginal. Laparoscopic and robotic hysterectomies. JSLS 16:519–524

Eltabbakh GH (2000) Effect of surgeon’s experience on the surgical outcome of laparoscopic surgery for women with endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 78:58–61

Holtz DO, Miroshnichenko G, Finnegan MO, Chernick M, Dunton CJ (2010) Endometrial cancer surgery costs: robot vs laparoscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 17:500–503

The Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission [Internet]. Hospital rates, charge targets and compliance. http://www.hscrc.state.md.us/. (Cited 2015, Sept 15)

Bureau of Labor Statistics [Internet]. Consumer Price Index (CPI). http://www.bls.gov/cpi/. (Cited April 15, 2015)

Iavazzo C, Papadopoulou EK, Gkegkes ID (2014) Cost assessment of robotics in gynecologic surgery: a systematic review. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 40:2125–2134

Zeybek B, Oge T, Kılıç CH, Borahay MA, Kılıç GS (2014) A financial analysis of operating room charges for robot-assisted gynaecologic surgery: efficiency strategies in the operating room for reducing costs. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc 15:25–29

Lenihan JP, Kovanda C, Seshadri-Kreaden U (2008) What is the learning curve for robotic assisted gynecologic surgery? J Minim Invasive Gynecol 15(5):589–594

Seamon LG, Fowler JM, Richardson DL et al (2009) A detailed analysis of the learning curve: robotic hysterectomy and pelvic-aortic lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 114(2):162–167

Woelk JL, Casiano ER, Weaver AL, Gostout BS, Trabuco EC, Gebhart JB (2013) The learning curve of robotic hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 121(1):87–95

Acknowledgements

We have no further acknowledgements. No financial compensation was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study received no funding.

Conflict of interest

Andrea M. Avondstondt, M.D. declares that she has no conflict of interest. Michelle Wallenstein, M.D. declares that she has no conflict of interest. Christopher R. D’Adamo, PhD. declares that he has no conflict of interest. Robert M. Ehsanipoor, M.D. declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Avondstondt, A.M., Wallenstein, M., D’Adamo, C.R. et al. Change in cost after 5 years of experience with robotic-assisted hysterectomy for the treatment of endometrial cancer. J Robotic Surg 12, 93–96 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11701-017-0700-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11701-017-0700-6