Abstract

Background

Obesity is a risk factor for chronic kidney disease (CKD) and a relative contraindication for renal transplantation. Bariatric surgery (BS) is an option to address this issue but we hypothesize that severe CKD is associated with a loss of efficacy of BS which could justify recommending it at an earlier stage of the CKD.

Methods

A retrospective study (n = 101 patients) to test primarily for differences in weight loss at 6 and 12 months according to estimated glomerular filtration rate categories (eGFR < 30 including patients on dialysis, 30–60, 60–90, and ≥ 90 ml/min/1.73 m2) was performed with multivariate analysis adjusted for sex, age, BMI, surgical procedure, and diabetes. We used a second method to confirm our hypothesis comparing weight loss in patients with stage 4–5 CKD (eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2, n = 17), and matched controls with eGFR ≥ 90 ml/min/1.73 m2.

Results

In the first comparison, the multivariate analysis showed a significant positive association between eGFR and weight loss. However, after exclusion of the subgroup of patients with eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2, the difference between groups was no more significant. In addition, percent total weight loss (%TWL) was significantly lower in patients with severe CKD compared to controls: − 15% vs − 23% at 6 months (p < 0.01); − 17% vs − 27% at 12 months (p < 0.01). The percent excess weight loss at 1 year reached 47% in patients with stage 4–5 CKD and 68% in controls subjects (p < 0.01). Surgery was a success at 12 months (weight loss > 50% of excess weight) in 38% of advanced CKD and 88% of controls (p < 0.01).

Conclusion

The efficacy of BS was reduced in patients with advanced CKD. These results support early BS in patients with early-to-moderate CKD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) has been recently estimated to at least 10% in the USA and Europe [1, 2]. CKD is causally associated with diabetes mellitus and hypertension, two conditions intimately associated with obesity. Obesity is also increasingly recognized as an independent risk factor for CKD and the development of end-stage renal disease (ESRD), through hemodynamic and metabolic mechanisms [3, 4]. For a given category of CKD, the prognosis is worse for obese patients. Indeed, when CKD is established, the decline of glomerular filtration is steeper for people with vs without obesity [5]. Moreover, access to renal transplantation (RT) is compromised for people with CKD combined with obesity [6, 7]. Indeed, several guidelines indicate that patients with a body mass index (BMI) above 40 or 45 should not be considered for RT [8].

Safety of bariatric surgery has been evaluated in patients with CKD [9]. Although the risks are clearly increased in this population with frequent co-morbidities, benefits are expected to balance them. Bariatric surgery may thus be proposed to patients eligible to RT with severe (stage 4) or end-stage (stage 5) CKD, in order to help them eliminate the main contraindication for the RT. However, optimal timing for bariatric surgery is an important issue, not yet addressed. In particular, whether the efficacy of bariatric surgery assessed on weight loss varies according to the stages of CKD is unknown. To address this question, we performed an observational retrospective study to compare, in severely or morbidly obese patients with the full range of CKD stages, the weight loss at 6 and 12 months after bariatric surgery.

Methods

Patient Selection and Data Sources

In this retrospective study, we examined data from patients from 4 surgical centers (Bichat-Claude Bernard Hospital (Paris, France), Louis-Mourier Hospital (Colombes, France), Antoine Béclère Hospital (Clamart, France), and Haut Levêque Hospital (Bordeaux, France)) who were or not on dialysis, who had no history of RT, who underwent bariatric surgery between June 2012 and August 2015, and who were followed up for at least 1 year.

Stratification and Outcomes

The population was stratified according to estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) levels (CKD-EPI equation–based estimation [10]): normal or high eGFR (≥ 90 ml/min/1.73m2), mild CKD (eGFR 60–90 ml/min/1.73 m2, stage 2), moderate CKD (eGFR 30–60 ml/min/1.73 m2, stage 3) or severe/end-stage CKD (eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2, stage 4–5, including dialysis). Our outcomes of interest were % total weight loss (%TWL) and %excess weight loss (%EWL), calculated as %EWL = total weight loss/(preoperative weight–weight corresponding to a BMI at 25 kg/m2), 6 months and 12 months after the surgical procedure. Complications were assessed both in the 30 days following surgical procedure according to the Clavien-Dindo classification [11] and in the long term according to the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) [12].

Statistical Analysis

To test for differences in weight loss at 6 and 12 months according to eGFR categories, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for each variable of interest. Data was then analyzed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) followed by Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparisons with eGFR categories (< 30, 30–60, 60–90, and ≥ 90 ml/min/1.73 m2) included as a within-groups factor. ANCOVAs were conducted controlling for preoperative BMI, type of surgery procedure (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) vs sleeve gastrectomy (SG)), diabetes (yes vs no), age, and gender.

In a second analysis, we selected patients with stage 4–5 CKD (eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2, n = 17) and matched them to 17 control patients with eGFR ≥ 90 ml/min/1.73 m2 (matching for sex, age, preoperative BMI, surgery procedure, and diabetic status) to compare weight loss in the two subgroups with a paired t test.

Results

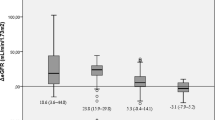

Among the 101 patients included, 17 had stage 4–5 CKD (eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 including 12 patients on dialysis), 19 stage 3 CKD (eGFR 30–60 ml/min/1.73 m2), and 33 stage 2 CKD (eGFR 60–90 ml/min/1.73 m2). Table 1 describes the main characteristics of the population according to baseline CKD stages. The groups differed by age, sex, and bariatric procedures. In univariate analysis, the weight loss assessed by %TWL or %EWL differed according to CKD stages at 6 and 12 months (Table 2, ANOVA, p < 0.05 for each comparison). In multivariate analysis, baseline CKD stages remained significantly associated with weight loss expressed as %TWL as well as %EWL at 6 and 12 months after bariatric surgery procedure (Fig. 1, p for trend < 0.001 for each comparison). However, after exclusion of the subgroup of patients with stage 4–5 CKD (eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2), the difference between groups was no more significant. This suggests that the loss of efficacy of bariatric surgery was observed specifically in patients with stage 4–5 CKD (eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2). To test further this hypothesis, and limit the contribution of potential confounding factors, we compared the weight loss in patients with CKD stage 4–5 CKD (eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2) and matched controls. Table 3 describes the characteristics of both groups. The surgery procedure was a SG for all but one matched pair. The %TWL and %EWL were significantly lower in the group with advanced CKD both at 6 and 12 months (Fig. 2a, b). Among the 17 patients with stage 4–5 CKD (eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2), two postoperative complications occurred: (1) a hypertensive crisis leading to a 5-day stay in intensive care, and (2) an acute respiratory illness episode associated with rhabdomyolysis leading to a 2-day stay in intensive care. Both episodes were classified stage IVa in the Clavien-Dindo classification [11]. There was no short-term complication that occurred in the control group and no complication according to the LABS classification neither in the group of patients with stage 4–5 CKD nor in the control group [12].

%total weight loss (a) and %excess weight loss (b) at 6 and 12 months in patients with stage 4–5 CKD (eGFR< 30 ml/min/1.73 m2) and matched patients with eGFR ≥90 ml/min/1.73 m2 (matching for age, sex, baseline BMI, surgery procedure, and diabetic status); p < 0.01 vs patients with severe CKD, at 6 months and 12 months

Discussion

This study showed that patients with advanced CKD (stage 4–5) have a blunted weight loss response to bariatric surgery, although less advanced CKD has no effect.

The efficacy of bariatric surgery, in terms of weight loss, in people with CKD is important for three main reasons. First, obesity is increasingly recognized as an independent risk factor for the development and progression of renal disease and observational studies suggest a potential interest of bariatric surgery for slowing down the decline of kidney function [5, 13]. A recent analysis of 4047 patients of the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) cohort revealed that bariatric surgery was associated with long-term protection against ESRD [14]. The on-going Bariatric Surgery for Obese patients with chronic Kidney Disease (BOKID) clinical trial aims at demonstrating whether bariatric surgery is superior to medical treatment of obesity to prevent the deterioration of kidney function in patients with severe or morbid obesity and stage 3 or worse CKD (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02612831?term=bokid&rank=1). Secondly, current guidelines and clinical practice often require patients with obesity to significantly lose weight before consideration of surgical eligibility to RT [15]. Indeed, access to the surgical site may be compromised by the thicker layers of the abdominal wall and intra-abdominal fat; moreover, excess weight is expected to increase the risk of anesthesia, the length of hospitalization, and the incidence of surgical complication usually associated with severe obesity. Thirdly, observational studies revealed that severe obesity is associated with a delayed recovery of graft function and increased graft failure rates [16]. Taken together, these observations have often led transplantation centers to restrict access to RT by establishing a BMI threshold about 35 kg/m2 with a high variability from one center (and sometimes surgeon) to another. Accordingly, in patients with stage 4–5 CKD, obesity is associated with a lower likelihood of RT, especially when BMI > 35 kg/m2 [6, 7, 17].

For the reasons mentioned above, it is crucial for nephrologists to manage and treat obesity in patients with CKD. Traditional weight loss diets (such as using general healthy eating principles) are considered as effective in people with CKD as in the general population [18], with a sustained weight loss of about 5–10%, which is insufficient for most patients with BMI > 35 kg/m2. In a review assessing the effect of lifestyle interventions for adults with severe obesity, control group-subtracted weight loss ranged from − 1.0 to − 6.5% over 6 to 48 months [19]. Bariatric surgery is clearly the most effective treatment for morbid obesity in terms of long-term weight loss, improvement of co-morbidities, quality of life, and decreases of overall mortality [20].

The issue of bariatric surgery timing in patients with CKD had not been addressed previously although it is a major concern. Indeed, a 30% increased risk of surgery-related complications was described for each increment in CKD stage even after adjustment for diabetes mellitus and hypertension [9]. However, laparoscopic methods have greatly improved the safety of bariatric procedures. Dependence on dialysis was not found to be an independent predictor of major morbidity post bariatric surgery [21]. The nephrology teams may thus be inclined to wait before proposing bariatric surgery. However, according to our findings, patients with severe or ESRD will take a lower benefit in terms of weight loss from the procedure and depending on the weight loss required, eligibility for RT may remain compromised. Our study assessed the impact of bariatric surgery in patients with CKD distinguishing the different stages of kidney failure. Indeed, we previously pointed on the importance of considering severe vs mild vs moderate CKD when assessing the clinical impact of bariatric surgery [22].

The design of our study makes it not possible to address mechanistic issues. However, several hypotheses can be raised. Firstly, the urgent need of weight loss in an impending RT project may have impacted the management of care before surgery with, potentially, less time for the preoperative phase including dietary and physical preparation. Secondly, the fear of malnutrition could particularly influence preoperative dietary management in CKD with a higher risk of surgical complications. Indeed, body composition of patients with severe CKD is modified, with a lower lean body mass, and a higher risk of undernutrition and sarcopenia [23]. This consideration is particularly relevant in patients suffering from combined renal failure and obesity [24]. Thirdly, energy expenditure, in two of its components (resting expenditure and physical activity), is reduced in patients with CKD and is a limiting factor for weight loss after bariatric surgery. Indeed, resting energy expenditure is lower due to reduced lean body mass and advanced CKD-associated sarcopenia is associated with a decrease in daily physical activity due to patient frailty and sedentary lifestyle [25,26,27]. Finally, the obesity paradox was well described in severe CKD [28, 29] (an apparent protection associated with obesity in patients with CKD) and could confuse the nephrology teams about the relevance of weight loss. Although we cannot document this hypothesis, it could have led the caregivers to attenuate the weight loss objectives after validation of eligibility for RT.

Our study provides reassuring data regarding the risks of bariatric surgery in patients with 4–5 CKD. We do not report any severe complications according to Clavien-Dindo’s and the LABS classifications, but we acknowledge the limited size of the sample [11]. However, our results are consistent with those of previously published data [30, 31].

Our study has several limitations. The sample size is limited. This reflects perhaps the reluctance of caregivers to propose bariatric surgery for patients with obesity and CKD. We have not systematically measured body composition. We cannot, therefore, support our mechanistic assumptions, particularly on the decrease in lean body mass in these patients. Finally, details on the modalities and the intensity of preoperative follow-up were not available. The currently on-going BOKID study, designed to assess the impact of bariatric surgery on kidney function in patients with stage 2 to 4 CKD, collects measurements body composition and thus will provide additional data to examine our hypotheses.

In summary, our findings suggest that patients with severe obesity and CKD get the best benefit from bariatric surgery in terms of weight loss when the intervention takes place before the stage 4–5 of kidney failure. Prospective data are warranted to confirm our observation.

Abbreviations

- INSERM:

-

Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale

- HUPNVS:

-

Hôpitaux Universitaires Paris-Nord Val de Seine

- AP-HP:

-

Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris

References

Hill NR, Fatoba ST, Oke JL, et al. Global prevalence of chronic kidney disease - a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0158765.

De Nicola L, Minutolo R. Worldwide growing epidemic of CKD: fact or fiction? Kidney Int. 2016;90(3):482–4.

Izquierdo-Lahuerta A, Martinez-Garcia C, Medina-Gomez G. Lipotoxicity as a trigger factor of renal disease. J Nephrol. 2016;29(5):603–10.

Griffin KA, Kramer H, Bidani AK. Adverse renal consequences of obesity. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2008;294(4):F685–96.

Yun HR, Kim H, Park JT, et al. Obesity, metabolic abnormality, and progression of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;72(3):400–10.

Toapanta-Gaibor NG, Suner-Poblet M, Cintra-Cabrera M, et al. Reasons for noninclusion on the kidney transplant waiting list: analysis in a set of hemodialysis centers. Transplant Proc. 2018;50(2):553–4.

Lassalle M, Fezeu LK, Couchoud C, et al. Obesity and access to kidney transplantation in patients starting dialysis: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0176616.

Association TR. The renal association assessment of the potential kidney transplant recipient. 2011.

Turgeon NA, Perez S, Mondestin M, et al. The impact of renal function on outcomes of bariatric surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23(5):885–94.

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–12.

Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):187–96.

Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery C, Flum DR, Belle SH, et al. Perioperative safety in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(5):445–54.

Coupaye M, Flamant M, Sami O, et al. Determinants of evolution of glomerular filtration rate after bariatric surgery: a 1-year observational study. Obes Surg. 2017;27(1):126–33.

Shulman A, Peltonen M, Sjostrom CD, et al. Incidence of end-stage renal disease following bariatric surgery in the Swedish Obese Subjects Study. Int J Obes. 2018;42(5):964–73.

European Renal Best Practice Transplantation Guideline Development G. ERBP Guideline on the Management and Evaluation of the Kidney Donor and Recipient. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(Suppl 2):ii1–71.

Chang SH, Coates PT, McDonald SP. Effects of body mass index at transplant on outcomes of kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;84(8):981–7.

Gill JS, Hendren E, Dong J, et al. Differential association of body mass index with access to kidney transplantation in men and women. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(5):951–9.

Lambert K, Beer J, Dumont R, et al. Weight management strategies for those with chronic kidney disease - a consensus report from the Asia Pacific Society of Nephrology and Australia and New Zealand Society of Nephrology 2016 renal dietitians meeting. Nephrology (Carlton) 2018;23(10):912–20

Hassan Y, Head V, Jacob D, et al. Lifestyle interventions for weight loss in adults with severe obesity: a systematic review. Clin Obes. 2016;6(6):395–403.

Yumuk V, Tsigos C, Fried M, et al. European guidelines for obesity management in adults. Obes Facts. 2015;8(6):402–24.

Andalib A, Aminian A, Khorgami Z, et al. Safety analysis of primary bariatric surgery in patients on chronic dialysis. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(6):2583–91.

Arapis K, Kadouch D, Caillieret O, et al. Bariatric surgery and chronic kidney disease: much hope, but proof is still awaited. Int J Obes. 2018;42(8):1532–3.

Foley RN, Wang C, Ishani A, et al. Kidney function and sarcopenia in the United States general population: NHANES III. Am J Nephrol. 2007;27(3):279–86.

Stenholm S, Harris TB, Rantanen T, et al. Sarcopenic obesity: definition, cause and consequences. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11(6):693–700.

Ravussin E, Gautier JF. Determinants and control of energy expenditure. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2002;63(2 Pt 1):96–105. Determinants et controle des depenses energetiques

Johansen KL, Lee C. Body composition in chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2015;24(3):268–75.

Baria F, Kamimura MA, Avesani CM, et al. Activity-related energy expenditure of patients undergoing hemodialysis. J Ren Nutr. 2011;21(3):226–34.

Degoulet P, Legrain M, Reach I, et al. Mortality risk factors in patients treated by chronic hemodialysis. Report of the Diaphane collaborative study. Nephron. 1982;31(2):103–10.

Salahudeen AK. Obesity and survival on dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41(5):925–32.

Modanlou KA, Muthyala U, Xiao H, et al. Bariatric surgery among kidney transplant candidates and recipients: analysis of the United States renal data system and literature review. Transplantation. 2009;87(8):1167–73.

Kienzl-Wagner K, Weissenbacher A, Gehwolf P, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: gateway to kidney transplantation. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(6):909–15.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Hansel reports grants from Amgen, Sanofi, personal fees from Sanofi, AMGEN, Novo Nordisk, Smartsante, Jalma, and MXS, outside the submitted work;

Dr. Arapis has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Kadouch has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Ledoux has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Coupaye has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Msika has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Vrtovsnik has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Marre reports grants and personal fees from Novo Nordisk, personal fees from Servier, personal fees from Merck, personal fees from Lilly, personal fees from Sanofi, and personal fees from Abbott, outside the submitted work;

Dr. Boutten has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Cherifi has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Courie has nothing to disclose.

Ms. Beslay has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Coupaye has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Cambos has nothing to disclose.

Dr. Roussel reports grants and personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees from Astra Zeneca, personal fees from Eli Lilly, personal fees from MSD, personal fees from Novo Nordisk, and personal fees from Janssen, outside the submitted work

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hansel, B., Arapis, K., Kadouch, D. et al. Severe Chronic Kidney Disease Is Associated with a Lower Efficiency of Bariatric Surgery. OBES SURG 29, 1514–1520 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-03703-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-03703-z