Abstract

Extant studies examining emotional labor and job satisfaction have generally been limited by examining only surface and deep acting. This study builds upon extant studies by introducing natural acting strategies and examines the moderating role of compensation. Based on structural equation modeling involving 326 frontline service employees across several service providers and industries in South Korea, this study showed that role clarity was positively related to all three emotional labor strategies, with natural acting being most prevalent. Further, this study showed that natural acting had a negative relationship to emotional exhaustion, and that perceived fairness of compensation positively moderated the relationship between emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Serving customers in a friendly and polite manner is a near-universal standard expected of service organizations. Because the manner in which service providers display their emotions and reactions to customers during interactions has a strong impact on the perceived quality of the service provided, service organizations tend to set a wide range of formal and informal behavioral display rules that guide verbal and nonverbal expression such as gestures, facial expression, and voice tone (Ashforth and Humphrey 1993). For example, many hotels require their receptionist to make guests feel welcome with a smile, to show solicitous concern so that guests feel cared for, and kindly respond to their demands. In order to comply with such display rules, service providers make an effort to control and manage their inner (i.e., felt) and/or outer (i.e., expressed) emotions to ensure an appropriate match to the expected expressive behavior of the organization. Even without an organization’s explicit direction and observation, a worker in on-demand service such as Uber might engage in managing their emotional display to ensure customer perception of high-quality service. Rosenblat and Stark (2016) noted that to avoid their services being deactivated, Uber’s customer rating system forces drivers to maintain near-perfect scores; in order to guarantee highly rated customer service, drivers are obligated, even if not formally required, to conform to perceived customers’ expectations and suppress any negatively felt emotions to deliver the impression of high-quality service. With respect to such situations, Hochschild (1979, 1983) introduced the concept of emotional labor, referring to an act of expressing the expected emotion defined by organization's display rules during service transactions.

Emotional labor is behavioral acting that requires some level of suppressing and managing genuine feelings and acting deliberately to display an emotion that is not concordant with how an individual feels. Emotional labor is rooted in emotional dissonance, which is a gap between employees’ felt emotion and required emotional display (Kruml and Geddes 2000; Hülsheger and Schewe 2011; Cossette and Hess 2012). For the most part, research in emotional labor in the service sector has centered around the choice of emotional labor strategy; that is how individuals manage to express positive emotions and suppress negative emotions, to meet their employers’ expectations of emotional display. The focus of emotional labor strategy is generally examined from two perspectives: either (a) service providers suppress their felt emotion and superficially show emotions they are required to express for their jobs (i.e., surface acting); or (b) they reappraise the situation from the customer’s point of view and deliberately modify their felt emotion and try to experience the appropriate emotions so that genuine emotional displays follow (i.e., deep acting). For example, if a hotel guest complains and makes excessive and unreasonable demands, frontline employees might be mandated to express a sincere apology, even though they initially felt disturbed. In order to display a sincere apology, these employees might engage in surface acting by pretending that they care about the guest’s welfare thus shaping their outer emotional performance. Alternatively, frontline employees might engage in deep acting and make an effort to understand the guest’s frustration and try to feel the actual emotions that they are expected to display.

With respect to managing emotions in the workplace, Ashforth and Humphrey (1993) introduced a possible third mode of emotional labor strategy: natural acting. Here, the emotion expected by the organization and the genuinely felt emotion of the employee are the same, thus service providers naturally express their felt emotion. One might wonder how simply expressing what they feel would be considered labor. Brotheridge and Lee (2002, 2003) argued that managing impressions and expressions requires constant self-monitoring regardless of the extent of the manipulation to the felt emotion to comply with emotional display rules. When performing natural acting, employees still have to put forth a conscious effort to ensure that their display coincides with the organization’s expectations (Ashforth and Humphrey 1993). In response, Diefendorff et al. (2005) developed a measurement of natural acting and empirically showed that this is a distinct strategy from surface and deep acting. Although a few researchers have shown an increased interest in natural acting in recent years (e.g., (Hoffmann 2016; Picard et al. 2018), research on natural acting is still in its early stage, warranting more research. As such, given that role clarity and emotional exhaustion have been studied extensively in the context of surface acting and deep acting, the first purpose of this study is to explore the effects of role clarity and emotional exhaustion on natural acting and to compare the effects of those across emotional labor strategies.

The second purpose of the current research is to examine the role of the perceived fairness of compensation in moderating the relationship between emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction. Shanshan and Chao (2017) conceptually proposed the role of financial and nonfinancial rewards in mitigating the level of emotional exhaustion and job dissatisfaction. Despite the increased interest in the role of a financial reward system in the context of emotional labor (Chi et al. 2011; Shanshan and Chao 2017), there is little empirical evidence to support the intuitive assumption that an individual’s perception of the reward system reduces the negative impact of emotional exhaustion on job satisfaction. Hence, this study attempts to test a framework of the emotional labor mechanism that incorporates the perceived fairness of compensation in the context of emotional labor. Consequently, the current study explores two research questions:

-

(1)

How are the impacts of role clarity as antecedent and emotional exhaustion as a consequence of the three emotional labor strategies different from one another?

-

(2)

Does the perceived fairness of compensation moderate the negative relationship between emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction?

In the following sections of this paper, we discuss the theoretical foundations concerning role clarity as an antecedent and emotional exhaustion as a consequence of the three emotional labor strategies, and present hypotheses to be tested. Subsequent sections concentrate on the methodology of the empirical study and a description of the results. A discussion of the theoretical and managerial implications and contributions is provided along with limitations and future directions for research as a conclusion.

2 Theoretical background and hypothesis development

2.1 Role clarity and emotional labor

Role clarity in the context of service encounters refers to a service provider’s perceptions about the appropriate and effective behavior associated with the interaction with customers, which includes the dimensions of clarity of role objective, expectation and responsibility, and actions (Amyx et al. 2014; Papastylianou et al. 2009). Role clarity is widely recognized as a key predictor of employee behavior. For instance, ambiguous demands or unclear expectations are related to low commitment to the organization’s goals and values (Singh et al. 1994; Babakus et al. 1999; Low et al. 2001). Conversely, role clarity has a positive relationship to an individual’s motivation to apply effort toward task performance, thereby enhancing emotional labor (Amyx et al. 2014; Lee et al. 2015; Nasurdin et al. 2015).

Surface acting and deep acting follow when integrative, clear behavioral role expectations are present (Brotheridge and Grande 2002; Brotheridge and Lee 2003; Gosserand and Diefendorff 2005; Diefendorff and Gosserand 2003). A role in a company is a set of expectations about behavior for a position, which reflects the values and goals of the organization that manifested through the expectations of the customer in service context (Rizzo et al. 1970; Ashforth and Humphrey 1993). The clearer and stronger an organization’s customer-oriented role performance expectations are, the greater likelihood that service providers engage in more active planning and conscious monitoring of their service interaction behaviors and expressions (Morris and Feldman, 1996). Through more or less structured role management of both direct (e.g., training, feedback, discussion, rituals) and indirect (e.g., stories and myths, metaphors, observation of models) experiences that lead to role understanding and clarity, service providers comes to learn the intensity, content, and variety of emotions that ought to be experienced and expressed while performing the service encounter role (Ashforth and Humphrey 1993). Therefore, if service providers have a clear understanding how they are expected to act in service encounter situations, and what sort of behavior and expression is related to the necessary or desirable consumer satisfaction results, the service provider is likely to be more confident when serving customer; this strengthens employees’ beliefs in their capabilities by adjusting their feelings and behaviors to meet the firms’ expectations (Conger and Kanungo 1987; Gist and Mitchell 1992; Li and Fang 2016). In this manner, service employees’ effort to satisfy the customer with a presentation of empathy and civility often entails suppression of negative emotions (Yagil and Medler-Liraz 2019). As a service provider understands their role expectation clearly, it becomes easier to observe their level of behavioral compliance with the role expectations; hence, the chance to detect a discrepancy between the perceived inner emotion(s) and appropriate expression and behavior is increased, which leads to engaging in a reduction process whereby individuals use emotion regulation strategies to reduce the discrepancy (Diefendorff and Gosserand 2003). Because employees’ negative inner feelings do not always conform to the emotions called for by their work roles, they often respond to role requirements by engaging in surface or deep acting (Huang and Brown Tom 2016).

Extant literature has provided evidence that role expectations for expressing positive emotions and suppressing negative emotions, also known as emotional labor, are common for frontline service providers (Wharton and Erickson 1993; Brotheridge and Grandey 2002) and are viewed as in-role job requirements by service employees (Diefendorff et al. 2005). For example, Morris and Feldman (1996) found that an organization’s effort to enhance the explicitness of frontline role expectations and display rules through classes, handbooks, and materials was likely to increase the frequency of desired emotional display, thus producing more experience and effort to control expressive behavior on the part of employees. Similarly, Amyx et al. (2014) and Lee et al. (2015) found that when an organization clearly specifies standards for the appropriate expression of emotions, service providers with sufficient training related to facial and bodily display were likely to follow the rules and standards regardless of how they actually feel, which in turn increased the level of emotional labor.

Although role clarity is expected to increase a service provider’s tendency to engage in emotional labor strategies, additional research has shown that the service provider is more likely to comply with the role demands through deep acting rather than surface acting. Spreitzer (1996) argued that when individuals understand their roles, those roles can take on personal meaning as individuals with an understanding of their role can judge the value of their work and therefore experience higher perceptions of meaning. Amyx et al. (2014) also argued that when a service provider has a full understanding and experience regarding what they are supposed to do and why, they are also likely to appreciate the importance of organizational goals and the value of the role demands.

Positive learning, training, and experience related to the value and goals of the organization and service role expectation enhance the employee’s psychological capital, and their development of their own identity as a service provider; Together, these are considered the skills and experiences needed in customer-contact positions (Kim et al. 2018). Service employees equipped with psychological capital may have sufficient motivation and capabilities to invest the necessary effort and resources in fulfilling job requirements, which enable them to readily alter their inner emotional state and, as a result, engage in deep acting rather than surface acting (Hur et al. 2016a, b). Further, the level of commitment to display rules and willingness to follow the rules depends on the discrepancy between the expected and felt emotion (Cossette and Hess 2012). Employees who value the organizational expectation and identify with their job roles are more likely to engage in deep acting since they are more easily convinced of the importance of regulating emotions toward customers (Ashforth and Humphrey 1993). In the same vein, Gosserand and Diefendorff (2005) showed that service providers who clearly understand the expectations and job responsibilities with respect to display rules are more motivated to engage in deep acting rather than surface acting. Similarly, Lee et al. (2015) and Grandey’s (2003) also found that emotional display rules increase influenced deep acting rather than surface acting. These results show that role clarity is expected to be more likely related to a service provider portraying deep acting rather than surface acting.

Following this logic, this study expects that when employees find their organization’s display rules congruent with their emotions, this will be more strongly related to their engaging in natural acting that displays such emotion—not because they are required, but because it is part of who they are.

When service providers are aware of the display rules which are congruent with their felt emotion, they are more likely to extend their effort toward displaying such emotions and persist in displaying these emotions over time (Cossette and Hess 2012). Therefore, when the role expectations of expected expressive behavior are clearly understood and in the context where employees find the discrepancy between the required display rules and felt emotion is minimal, the motivation to express such emotion becomes intense, and employees willingly comply through natural acting. Thus:

H1

Role clarity is positively related to the three emotional labor strategies.

H2

Role clarity is more strongly related to natural acting than to deep acting.

H3

Role clarity is more strongly related to deep acting than to surface acting.

2.2 Emotional labor strategies and emotional exhaustion

While research concerning the impact of emotional labor has investigated many variables as outcomes of acting, emotional exhaustion appears to be more common than others (see Hollet-Haudebert et al. 2011). Emotional exhaustion is a chronic state of depleted energy and being drained which people often associate with being burned out (Singh et al. 1994; Wright and Cropanzano 1998; Kumar et al. 2014).

In the context of emotional labor, emotional exhaustion is an outcome of emotional dissonance in that the needs to express the felt emotion conflict with the requirements of the organization at the same time, which is thought to drain emotional resources (Demerouti et al. 2001; Lewin and Sager 2009). Prior research has shown that the performance of emotional labor increased the level of emotional exhaustion (Jackson et al. 1986; Julian 2008; Rutherford et al. 2009; Kumar et al. 2014; Lee et al. 2015). Hence, this study expects that the greater the degree felt emotion is manipulated, the greater the level of emotional exhaustion is experienced. When service providers need to stimulate emotions that they do not actually feel, they need to carefully and cognitively choose their verbal and nonverbal expressions. During the management of their own emotions, especially when the felt emotion and expected display greatly conflicts, service providers are likely to suppress and deny their genuinely felt emotions and may experience energy depletion and fatigue (Grandey 2000; Zhang et al. 2016). Choi et al. (2019), for example, showed that as the intensity of demand for emotional labor intensified, service productivity decreased due to accumulated fatigue. The more that service providers’ “real” feelings conflict with expected emotions, the more psychological energy and effort are required for them to display appropriate emotions, thus leading to a higher level of emotional exhaustion. In this manner, deep acting is likely to be related to less emotional exhaustion than surface acting since deep acting involves reappraising the situation to manage inner feelings, which decreases the emotional dissonance (Gross 1998). Surface acting is likely to be related to a higher level of emotional exhaustion than deep acting because surface acting manipulates only the expressive aspect of the emotion, in turn, the emotional dissonance remains (Gross 1998; Kruml and Geddes 2000). Similarly, Brotheridge and Lee (2002, 2003) found that surface acting requires a high level of self-monitoring compared to deep acting due to the level of required control and modification of expressive behavior and emotions to meet standards of appropriateness; thus, surface acting is more likely to result in negative consequences. Grandey (2000, 2003) also found similar results that surface acting predicted a higher level of emotional exhaustion than deep acting.

Diefendorff et al. (2005) argued, however, that the display of naturally felt emotions at work would not be associated with emotional dissonance and burnout. Although self-monitoring is still related to natural acting in order to comply with the display rules (Diefendorff et al. 2005; Cossette 2014), the emotional discrepancy is minimal, suggesting less effort needed to manipulate the display and manage impressions (Cossette and Hess 2012). In this case, service providers do not need to change their expressed affect since the display is congruent with inner feelings; in other words, since employees do not feel emotional dissonance (Cossette and Hess 2012), their job attitudes are not likely to be damaged, but rather enhance their well-being (Kim et al. 2002; Hülsheger and Schewe 2011). Ashforth and Humphrey (1993) and Kiely (2005) argued that if the organizational display rule is consistent with the employee’s personal values, the service provider would have an opportunity to act out their own valued identity, hence the work becomes less stressful and even enhances their psychological well-being. Similarly, Kim et al. (2002) found that the self-determined motivation to express positive emotions was positively correlated with psychological well-being, which augments emotional resources and reduces emotional exhaustion. Therefore:

H4

Surface acting is positively related to emotional exhaustion.

H5

Deep acting is positively related to emotional exhaustion.

H6

Surface acting is positively related to greater levels of emotional exhaustion than is deep acting.

H7

Natural acting is negatively related to emotional exhaustion.

2.3 Emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and moderating role of the perceived fairness of compensation

Emotional exhaustion has been considered a critical predictor of job dissatisfaction (Babakus et al. 1999; Kumar et al. 2014). Because emotional exhaustion decreases a service provider’s emotional resources to respond in performing the expected service (Hobfoll 2001), an employee who experiences high levels of emotional exhaustion is likely to have greater frequency of fatigue, complaints, and work-related depression (Baba et al. 2009). An emotionally exhausted employee may attribute their emotional depletion to the source of work stressors, job demands, and the work environment, which is positively related to apathy toward their job, and lower job satisfaction (Sawyerr et al. 2009). In line with the results of a great deal of research concerning the impact of emotional exhaustion (c.f., Brewer and Clippard 2002; Grandey et al. 2005; Sager et al. 2006; Rutherford et al. 2009), this study hypothesizes:

H8

Emotional exhaustion is negatively related to job satisfaction.

While the negative relationship between emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction has been previously demonstrated, the current study expects the organization’s reward system to moderate the negative impact of emotional exhaustion. A reward system is one service quality control method used by an organization to obtain the desired behavior and service from employees (Babakus et al. 1999; Chung and Schneider 2002). As the reward system motivates the performance of the desired behavior, an employee can expect the recognition and compensation to be earned when performing such behaviors. In this manner, the employee’s job attitude which resulted from accomplishing the organizational goal is largely determined by the application of incentives and perceived fairness in compensation (Steinberg 1999; Nasurdin et al. 2015; Shanshan and Chao 2017; Elmadağ and Ellinger 2018). For example, Rosenblat and Stark (2016) noted that because Uber’s business model discourages the cultural practice of customers providing gratuities, the reward system fails to acknowledge and compensate a driver’s emotional labor, which leads to the driver’s dissatisfaction with Uber’s platform. Similarly, frontline service providers of a retail bank felt distressed and unsatisfied when they felt they were not well rewarded for their contributions and efforts to satisfy their workplace’s demands (Julian and Ramaseshan 1994), Elmadağ and Ellinger (2018) also found the extrinsic rewards increased employee commitment to the organization and customer orientation.

When interacting with the customer, a service provider is emotionally exhausted when they have few emotional resources to recover, due to the emotional labor in which they engage. Their depleted emotional resources are likely to be recuperated if they perceive the consequences of the emotional labor in which they engaged to be recognized and worthwhile. Consequently, perceived fairness in compensation justifies engaging in emotional labor (Adelmann 1995; Constanti and Gibbs 2005; Shanshan and Chao 2017), thus alleviating the impact of by-products of such labor on job satisfaction. In a context where compensation is perceived as a link to the performance of emotional labor, the impact of emotional exhaustion on job satisfaction is likely to be moderated by the perceived fairness in compensation. Thus:

H9

The perceived fairness in compensation moderates the negative relationship between emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction wherein greater levels of perceived fairness predict greater levels of job satisfaction.

3 Method

3.1 Data collection and samples

Frontline service employees in South Korea across several service providers and industries—as shown in Table 1—completed a self-administered survey. South Korea was selected as a location for this study because it is a country with well-developed service economy. Surveys were distributed and collected by a professional research company. The survey questionnaires were distributed to 1000 frontline service providers through the research company’s mailing system. A total of 330 surveys were returned. After eliminating four incomplete surveys for quality purposes, a total of 326 responses were used for analysis. The sample size meets the recommended minimum subject-to-variable ratio of at least 20:1 (Hogarty et al. 2005; Hair et al. 2010).

The ages of the respondents were evenly distributed, ranging from 20 to 60 years old, and were relatively evenly distributed by gender, with 49.1% male. The distribution of respondents’ education levels had a tendency toward a college level; 66% of respondents had either begun or had completed their bachelor’s degree studies. 30% of the respondents had completed senior high school as their highest level of education, while 4% held a graduate degree. The number of years worked for the company ranged from one to more than 15 years; approximately half of the respondents worked for the company for fewer than 5 years. The distribution of professions was not extremely skewed, and the diversity of occupations of the respondents indicates that the results of the current study describe the general workplace environment, rather than representing a particular service sector.

3.2 Measures

The measurements used for each variable were adapted from the relevant literature in emotional labor and services research. Role clarity was measured with a role ambiguity scale from Hollet-Haudebert et al. (2011), which was based on one originally developed by Rizzo (1970). The four items of role clarity measured the extent to which a service provider knows what the company’s expectations regarding the appropriate behaviors are. The five items measuring the level of emotional exhaustion were adopted from Hollet-Haudebert et al. (2011) as well, which was based off the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS). These five items measure the degree of frustration and discouragement about work and level of emotional drain. The definition and measurement for three modes of emotional labor were from Diefendorff et al. (2005), which used the measurements of surface acting and deep acting that were developed by Grandey (2003), whereas items of natural acting were based on Kruml and Geddes (2000). Perceived fairness in compensation was measured with three items developed by Foreman and Money (1995). To assess employees’ level of job satisfaction, four items from Taylor (2014) were adopted, which were based on the Job Satisfaction Index (Brayfield and Rothe 1951). All items were answered on 7-point Likert-type scales (1 = “completely disagree”; 7 = “completely agree”). To ensure a reliable and effective translation, the current research opted for the collaborative approach and conventional "translate-back translate" approach (Brislin 1980; Douglas and Craig (2007). Two bilingual native marketing faculty of Korea performed an independent, parallel translation of the original English questionnaire into Korean. A review meeting was held including the translators and an independent reviewer to resolve any inconsistencies. The final Korean version was translated back into English by American bilingual faculty who are familiar with both cultures. The original and back-translated English versions were reviewed to ensure the equivalence in meaning. In the end, the translated and agreed upon questionnaire was pretested by monolingual and bilingual service providers and further revised based on recommendations to improve the clarity and comprehension communication and translation.

3.3 Analysis strategy

Following the two-step modeling approach to structural equation modeling (SEM) (Anderson and Gerbing 1988), the measurement model was examined before testing the hypothesized structural model.

The research model included “Industry Sector” as a control variable, which was not significantly associated with job satisfaction. In order to test the moderating effect of the perceived fairness in compensation between emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction, we followed a two-step procedure (Ping 1995) using AMOS and SPSS 21.0. software.

4 Results

4.1 Measurement model assessment

All items were subjected to a principal components factor analysis using Varimax rotation. The factor loadings for the items are provided in Table 2. Each item’s standardized loading on the appropriate latent variable was significant and greater than 0.65 (p < 0.01). Table 2 shows that the construct reliability estimates ranged from 0.806 to 0.902, greater than the 0.7 cut off, which is the suggested benchmark for acceptable internal consistency (Hair et al. 2010). The average variance extracted (AVE) estimates ranged from 0.619 to 0.827, in which values for all constructs are above the threshold of 0.5 (Fornell and Larcker 1981; Hair et al. 2010).

The square root of AVE of each construct exceeds the correlation of that construct with all other constructs (Table 3) indicating adequate discriminant validity of all constructs (Chin 1998).

The measurement model achieved a good fit with the data; χ2 = 690.133, df = 303, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.949, TLI = 0.941, NFI = 0.914, IFI = 0.950, RMSEA = 0.063.

4.2 Test of moderating effect

Given the acceptable fit demonstrated by the measurement model, we then tested the structural model with and without the moderating variable, perceived fairness in compensation, to validate the effect of the interaction term in the proposed research model (Ping 1995). The difference in chi-square value of the model with and without the interaction term was 50.62, which is greater than the chi-square value of 41.337 for 27 degrees of freedom at the 5% level of significance (Proposed Research Model with interaction: χ2 = 939.551, df = 366, competing model without interaction: χ2 = 888.931, df = 338; Δ χ2 = 50.62, p < 0.01). These results provide evidence that the model with the interaction term is better than one without. The fit indices of the proposed research model were also acceptable; CFI = 0.925, TLI = 0.917, NFI = 0.884, IFI = 0.926, RMSEA = 0.069.

4.3 Hypotheses testing

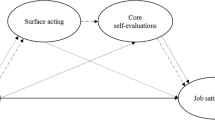

Figure 1 shows path estimates in which all paths, except H5, were significant and in the direction that supported the proposed hypotheses.

4.3.1 Effect of role clarity to emotional labor

As hypothesized, role clarity was a positive and significant antecedent to all three modes of emotional labor strategy, and was predictive of the strategies posited. Service providers with necessary information and clear understanding of their role expectations were likely to follow the display rules, and showed an increased the level of engagement in emotional labor, thus H1 was supported. The critical ratios for differences between parameter analyses were performed for the pairwise comparison among three paths; the value of the critical ratio (CR) between paths larger than 1.96 in absolute value is considered as significant at p < 0.05. The results show that the association of role clarity with natural acting was significantly stronger than with surface acting (CR = 4.692, p < 0.05) or with deep acting (CR = 2.088, p < 0.05), therefore H2 was supported (Table 4). The association of role clarity with deep acting was significantly stronger than with surface acting (CR = 3.178, p < 0.05), consequently, H3 was supported.

4.3.2 Effects of emotional labor to emotional exhaustion

Hypotheses 4–7 predicted the relationships between each of the three emotional labor strategies and the level of emotional exhaustion. As expected, surface acting was related to a higher level of emotional exhaustion (γ = 0.410, p < 0.01), whereas natural acting was related to a lower level of emotional exhaustion (γ = − 0.269, p < 0.01), suggesting that performing surface acting is detrimental to employees’ mental health at work and providing support for hypotheses 4 and 7. Deep acting, however, was not significantly related to emotional exhaustion (γ = 0.085, p = 0.304), therefore hypothesis 5 was not supported. However, the beta weight of the relationship between deep acting and emotional exhaustion was positive, which was the expected direction that we hypothesized. Although we could not confirm the hypothesized relationship between deep acting and emotional exhaustion, our findings are consistent with empirical results of previous studies by Grandey (2003), Kim (2008) and Jeon (2016), which reported that whereas surface acting directly increased the level of emotional exhaustion, deep acting did not significantly increase the level of emotional exhaustion. Grandey (2003) suggested the reason to be that the effort to reduce emotional dissonance by engaging in deep acting may restore an employee’s emotional resources, which may help minimize emotional exhaustion.

To further examine the relationship between types of acting and emotional exhaustion, we performed post hoc analyses to assess the statistical significance of path coefficients as checked by the critical ratio. As shown in Table 5, the association of emotional exhaustion with surface acting was strongest compared to its association with deep acting (CR = 2.705, p < 0.05) or with natural acting (CR = 6.264, p < 0.05), therefore providing support for hypothesis 6. The strength of the relationship between natural acting and emotional exhaustion was higher than the relationship between deep acting on emotional exhaustion (CR = 3.049, p < 0.05).

4.3.3 Effects of emotional exhaustion, job satisfaction, and moderating effect of perceived fairness in compensation

Hypothesis 8 was supported in that emotional exhaustion was negatively related to job satisfaction (γ = − 0.347, p < 0.01), and the relationship was positively moderated by the perceived fairness in compensation, (γ = 0.075, p < 0.01), thus providing evidence to support hypothesis 9. Specifically, the negative relationship between emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction became weaker (stronger) when the perceived fairness of compensation was high (low).

5 Discussion

This study empirically demonstrated relationships between role clarity and emotional labor strategies, and the impact of these on emotional exhaustion. Surface acting was related to greater amounts of emotional exhaustion, while natural acting was related to lower amounts of emotional exhaustion. In turn, the relationship between emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction was moderated by the perceived fairness of compensation.

5.1 Theoretical implications

These findings from the current study not only support the notion proposed by Hochschild (1983) and other extant research which showed that emotional labor could predict dysfunctional consequences for the individual (emotional exhaustion) and the organization (job satisfaction), but also extend the realm of emotional labor research by empirically showing the positive and significant role of natural acting in the context of service delivery.

Previous research has focused on the negative aspects of engaging in emotional labor, in that employees either fake unfelt emotion or suppress and reshape their genuine emotion. Ashforth and Humphrey (1993) raised the concern that this conception of emotional labor has drawn heavily on a limited perspective, which readily overlooked positive engagement in emotional labor. Built upon the few studies on natural acting, the current study elaborated a theoretical framework that incorporated three emotional labor strategies (Surface acting, Deep acting, and Natural acting) simultaneously and empirically tested and compared the impacts of antecedent and consequence of these strategies.

We found that role clarity enhances the performance of emotional labor, which is consistent with past research exploring the relationship between role ambiguity and job performance (Amyx et al. 2014). Furthermore, in the current study, we found that engaging in natural acting is more influenced by role clarity compared to engaging in surface acting or deep acting. Ashforth and Humphrey (1993) suggested a possible reason for this finding, proposing that natural acting is a chance to express the authentic self (i.e., who they are), rather than to show what they are required. The finding also supports an explanation based in self-determination theory (Cossette and Hess 2012), that employees are more motivated to express themselves especially when organizational rules are congruent with their inner feelings.

In line with previous research concerning the negative influence of emotional labor on job outcomes, this study showed that emotional exhaustion is clearly related to lower job satisfaction. Furthermore, we extended the understanding of this relationship by testing the moderating role of perceived fairness of compensation. With respect to the function of the reward system in the context of emotional labor, Ashforth and Humphrey (1993) proposed that various rewards and punishments are likely to reinforce the internalization of the emotions that ought to be experienced and expressed while performing the work role. The current research empirically demonstrated that the perceived fairness of compensation moderates the negative relationship between emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction in that the negative effect of emotional exhaustion on job satisfaction became weaker when the perceived fairness of compensation was high.

5.2 Managerial implications

As a way to manage quality and consistent service to customers, service-oriented companies have asked their employees to follow an emotional display rule. To follow such a rule, a service provider tends to engage in emotional labor, which has been understood to be surface acting or deep acting. There are several reasons why managers need to pay special attention to emotional labor management and natural acting.

First, a customer may feel the authenticity of emotional labor. Employee emotions have a direct impact on customer emotions, organizations need to be aware of the sincere and authentic emotional contagion from employees to customers (Garry 2008; Wang 2009). Keiser (1988) and Hennig-Thurau et al. (2006) recognized that employees trying to fake emotion could backfire because customers are neither willing to engage with, nor pay for inauthenticity. As a result, the perceived level of authenticity may influence the perceived level of service quality (Pugh 2001; Groth et al. 2009), the amount of money spent in the store (Seger-Guttmann and Medler-Liraz 2016), customer satisfaction (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2006; Hur et al. 2015), rapport (Medler-Liraz 2016), revisit intention (Tsai 2001; Tsai and Huang 2002; Gountas et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2012), employee financial rewards such as tips (Koku and Savas 2016), product/service attitude (Howard and Gengler 2001), and loyalty (Groth et al. 2009; Medler-Liraz 2016). Performing deep acting could be an ideal strategy to enhance the authentic emotion display; a service provider who engages in deep acting adopts an empathic stance toward the customer as deep acting is more consistent with a concern for one’s customers compared to surface acting (Ashforth and Humphrey 1993). However, deep acting is less authentic compared to natural acting in the sense that employees still reshape their genuine emotions to manage the displayed expressions. Employees who engage in natural acting willingly express the required emotion without deliberate effort prompting the desired emotions, making the authenticity of the displayed emotion compelling.

A second reason managers need to be attuned to emotional labor management and natural acting is that employees should be considered internal customers whom the organization needs to serve and for whom they need to provide a healthy workplace environment. This study showed that surface acting and deep acting are likely to hurt job satisfaction, which has been used as a proxy for well-being at work (Grandey 2000). Emotional exhaustion also damages employee well-being (Cossette and Hess 2012). Based on the empirical result that natural acting reduced emotional exhaustion, including natural acting to an organization’s internal emotional labor management program should be beneficial alongside avoiding an excessive emphasis on superficial appearance which increases engagement in surface acting and deep acting. Expressing who they are, and feeling emotions naturally at work is one way to make a job more enjoyable (Ashforth and Humphrey 1993; Kiely 2005).

Third, the finding that role clarity increases the level of emotional labor suggests that organizations should be cognizant of the type and level of education/training provided to service employees. Ashforth and Humphrey (1993) pointed out that organizational efforts to promote their display rules are less likely to succeed and may even backfire as the service providers perceive this to be heavy-handed. For example, Wickham and Collins (2004) and Walsh and Hammes (2017) researched the danger of using service scripts because the use of service scripts contributes to employee emotional resource depletion and may exacerbate emotional labor, which enhances employee discriminatory behaviors toward customers. Furthermore, repetitive performance of surface acting is also likely to be associated with negative work-related outcomes such as burnout, dissatisfaction, decreased job performance, and voluntary turnover (Grandey 2000; Lai et al. 2020; Sandiford and Seymour 2011; Sawyerr et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2016). Previous research has demonstrated that, despite the acknowledged value ascribed to emotional training in service industries (Johanson and Woods 2008), there appears to be weak and ineffective training in this regard, with little if any consideration to the emotional issues that might emerge on the job (Van Maanen and Kunda 1989; Shani et al. 2014). An explanation for this lack of adequate training in the service industry could be that the turnover rate in many service industry jobs is quite high (Poulston 2008), thus the cost of such training isn’t perceived to be worth the benefit (Shani et al. 2014). The results of this study should encourage managers to consider not only the costs of training, but the opportunity costs of neglecting effective emotional labor training in their cost–benefit analyses.

Additionally, companies need to create a workplace environment where employees naturally feel the expected emotion, rather than leaving them to deal with emotions they did not feel during interactions with customers. Previous research discussing the impact of customer misbehavior toward service providers (e.g., Grandey et al. 2004, 2007; Fisk et al. 2010; Kim et al. 2012; Yagil and Medler-Liraz 2019) showed that dysfunctional customers who behave unreasonably are likely to demand a high level of emotional labor and emotional exhaustion from service employees. The stress appraisal of a dysfunctional customer is likely to induce surface acting (Harris and Daunt 2013) because it would be hard for service providers to embrace unreasonable behaviors and empathize with these customers. Kim et al. (2019) also emphasized the importance of organizational support within the context of boundary spanning emotional labor that raises both the customer orientation and self-efficacy of the service providers when customers display deviant behavior. This highlights the importance of customer education as well as the active protection of employees from dysfunctional customers.

The ability of an organization to encourage natural acting will be dependent upon that organization’s approach to customer service. Organizations that adopt a “the customer is always right” mentality may risk sending a message to employees that natural acting is not desirable. Furthermore, such an approach may increase the likelihood of conflict between customers and service employees (e.g., Grandey et al. 2004), and in fact subject service employees to illegitimate complaints (Kim and Baker 2020) and to experience customer bullying as part of the job (Bishop and Hoel 2008). In light of this, organizations should take a holistic approach to their customer service policies and consider their employees not merely as human resources to enact customer service strategies, but as partners in the organization’s success.

Also, it should be noted that, even though a statistically significant relationship between deep acting and emotional exhaustion wasn’t present, the association appeared positive, suggesting that the greater level of deep acting is related to greater levels of emotional exhaustion. Managers should observe whether their employees make an excessive effort to empathize with customers’ frustration in order to express the organizationally desired feeling. It is relatively easy for managers to observe one’s level of compliance with the display rules by facial and bodily expression, but is not as easy to monitor an employee’s inner processes to commit to such rules. As natural acting results in positive work-related outcomes, we recommend that HR policies and general corporate strategy and culture should recognize, value, and support service providers engaging in natural acting.

The finding of the positive effect of natural acting encourages management to develop a selective staffing process that leads to hiring individuals whose self is congruent with organizational demands and values, which increases the engagement of natural acting. Karatepe and Karadas (2016) and Yoo and Arnold (2014) empirically showed the importance of employee alignment; the fit between an employee’s desires and personal likes and the job demands alleviates stress and strain/burnout, which eventually fosters work engagement. Furthermore, Ashforth and Humphrey (1993) argued that natural acting may increase self-efficacy and task effectiveness, and previous research has shown that individuals are more attracted to organizations that are similar to them in terms of organizational values and goals than to organizations that are dissimilar Rentsch and McEwen (2002). Increasing a sense of perceived supplementary person-organization and person-job fit helps potential employees ascertain their sense of attraction to the organization and subsequent success at work (Kristof 1996; Carless 2005).

Based on the results presented, hiring individuals aligned with the company’s values and vision is recommended so that the demonstration of genuine and authentic emotional displays by employees naturally occurs. One approach to doing this is to use realistic job previews (e.g., Wanous 1973) which can help reduce involuntary turnover because they encourage self-selection (Wanous 1992); as Morris and Feldman (1996) posited, “Organizations that make explicit their emotional labor requirements during the selection process can help individuals decide beforehand whether their expressive behavior matches the organization's display norms” (p. 1005). In the service sector, this approach has been shown to increase job satisfaction and reduce turnover (Raub and Streit 2006).

The finding on the moderating role of compensation between emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction emphasizes the importance of rewarding and recognizing employees’ performance, especially when that performance is contingent upon emotionally exhausting activity. This result reinforces Terblanche (2016) who suggested that service employees should be rewarded if they perform the desired behavior consistently.

It is generally believed that service education and training are necessary to help employees learn how to provide sincere hospitality and how to use more appropriate and possibly beneficial methods to manage their emotions (Ang Chooi Hwa 2012). In the current study, however, the surface and deep acting strategies a service provider chose to comply with the emotional display rules were positively related to emotional exhaustion. The high level of emotional exhaustion associated with accomplishing the emotional tasks and expectations is more strongly related to a negative emotional state toward the work environment, which service providers find frustrating and unsatisfying.

The current research also demonstrated that performing natural acting was associated with a decreased level of emotional exhaustion, which is consistent with the recent finding of Picard et al. (2018). In line with an emotional dissonance approach that previous research has taken, we attribute the positive effect of natural acting to a minimal discrepancy between required and felt emotion. Because the felt emotional matches display rules, service providers are less likely to work up the emotion in the way surface acting or deep acting requires, rather feeling positive about themselves and their work might result in a sense of personal accomplishment, an intrinsic motivator.

6 Conclusions, limitations and future research

The current study aimed to better understand emotional labor by examining an emotional labor strategy that had largely been neglected in previous research, natural acting, and also examined the moderating role of perceived fairness in compensation on the negative outcomes of emotional labor. The results suggest the need to recognize ‘natural acting’ as a distinct emotional strategy in research on emotional labor.

Future research on emotional labor should benefit from taking a multi-dimensional approach and comparing the impact of all three modes of emotional labor. A future research agenda that is encourage by the current research would not only incorporate a multinational approach to examining emotional labor strategies and exhaustion, but also take into consideration organizational strategy when it comes to customer service orientation (Lytle and Timmerman 2006) and its relationship on organizational performance and its service employees.

Furthermore, while this study focused on the relationship between natural acting and emotional exhaustion, and the eventual association with job satisfaction, emotional exhaustion is also considered to be a primary antecedent measure for other job-related attitudes such as organizational commitment (Babakus et al. 1999; Rutherford et al. 2009) and turnover (Lee and Ashforth 1996; Wright and Cropanzano 1998; Shih-Tse Wang 2014; Hur et al. 2016a, b). Future research could adopt a robust methodology allowing for a causal examination of the effect of natural acting on different job-related attitudes and outcomes that have been studied extensively in the context of surface- and deep acting.

Although emotional labor tends to be considered in the context where employees are expected to express positive emotions and suppress negative emotions, it is important to note that the use of emotional acting does not always mean that the service providers experience negative emotion but fictitiously express the positive emotion; it means that the displayed emotion differs from the felt emotion. Future research would benefit from seeing the differences in three modes of emotional labor on the types of emotions as well as the mechanism underlying emotional expression.

While perceived fairness in compensation was found to be effective in reducing the negative effect of emotional exhaustion on job satisfaction, more research studying the effective management of tangible and intangible rewards would be valuable. For example, the perceived fairness in compensation not only moderates the negative influence of emotional exhaustion on job satisfaction but also enables the service providers in managing work-related stress and coping with work pressure more effectively (Amabile et al. 1994). Further research to understand the relationships between three modes of emotional labor and reward system as well as their relative impact on various job-related outcomes would be beneficial.

Finally, Ashforth and Humphrey (1993) proposed that compliance with display rules through surface acting or deep acting might, over time, foster alignment between the expression of emotion and the experience of emotion, i.e., natural acting. Studies examining the dynamics of an evolutional aspect of emotional labor strategies is an avenue ripe for future research.

Although this study has several important theoretical and managerial implications, it is important to also mention its limitations. The sample consisted of respondents from a single country (i.e., South Korea), suggesting that the results of this study need to be validated in other countries and/or settings. Therefore, future studies investigating other national settings to see if emotional labor strategies have an effect on emotional exhaustion, and subsequent job satisfaction would complement this study nicely (Fig. 1).

References

Adelmann PK (1995) Emotional labor as a potential source of job stress. In: Sauter SL, Lawrence R (eds) Organizational risk factors for job stress. American Psychol Association, Washington, DC, pp 371–381

Amabile TM, Hill KG, Hennessey BA, Tighe EM (1994) The work preference inventory: assessing intrinsic and extrinsic motivational orientations. J Personality Soc Psychol 66(5):950–967

Amyx D, Sharma D, Alford BL (2014) The influence of role ambiguity and goal acceptance on salesperson performance and commitment. Mark Mange J 24(1):52–65

Anderson JC, Gerbing DW (1988) Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull 103(3):411–423

Ang Chooi Hwa M (2012) Emotional labor and emotional exhaustion. J Mange Res 12(3):115–127

Ashforth BE, Humphrey RH (1993) Emotional labor in service roles: the influence of identity. Acad Mange Rev 18(1):88–115

Baba VV, Tourigny L, Wang X, Liu W (2009) Proactive personality and work performance in China: the moderating effects of emotional exhaustion and perceived safety climate. Can J Admin Sci 26(1):23–37

Babakus E, Cravens DW, Johnston M, Moncrief WC (1999) The role of emotional exhaustion in sales force attitude and behavior relationships. J Acad Mark Sci 27(1):58–70

Bishop V, Hoel H (2008) The customer is always right?: Exploring the concept of customer bullying in the British Employment Service. J Consum Cult 8(3):341–367

Brayfield AH, Rothe HF (1951) An index of job satisfaction. J Appl Psychol 35(5):307–311

Brewer EW, Clippard LF (2002) Burnout and job satisfaction among student support services personnel. Hum Resour Dev Q 13(2):169–186

Brislin RW (1970) back translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross-Cult Psychol 1(3):185–216

Brotheridge CM, Grandey AA (2002) Emotional labor and burnout: comparing two perspectives of “people work.” J Vocat Behav 60(1):17–39

Brotheridge CM, Lee RT (2002) Testing a conservation of resources model of the dynamics of emotional labor. J Occup Health Psychol 7(1):57–67

Brotheridge CM, Lee RT (2003) Development and validation of the emotional labour scale. J Occup Organ Psychol 76(3):365–379

Carless SA (2005) Person-job fit versus person-organization fit as predictors of organizational attraction and job acceptance intentions: a longitudinal study. J Occup Organ Psychol 78(3):411–429

Chi NW, Grandey AA, Diamond JA, Krimmel KR (2011) Want a tip? Service performance as a function of emotion regulation and extraversion. J Appl Psychol 96(6):1337–1346

Chin WW (1998) Commentary: issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Q 22(1):vii–xvi

Choi DH, Noh YH, Rha JS (2019) Work pressure and burnout effects on emergency room operations: a system dynamics simulation approach. Serv Bus 13(3):433–456

Chung BG, Schneider B (2002) Serving multiple masters: role conflict experienced by service employees. J Serv Mark 16(1):70–87

Conger JA, Kanungo RN (1987) Toward a Behavioral Theory of Charismatic Leadership in Organizational Settings. Acad Mange Rev 12(4):637–647

Constanti P, Gibbs P (2005) Emotional labour and surplus value: the case of holiday ‘reps.’ Serv Industries J 25(1):103–116

Cossette M (2014) Emotional labor through the lens of self-determination theory. In: Gagné M (ed) The oxford handbook of work engagement, motivation, and self-determination theory. Oxford University Press, New York, NY, pp 259–275

Cossette M, Hess U (2012) Emotion regulation strategies among customer service employees: a motivational approach. In: Ashkanasy NM, Härtel CEJ, Zerbe WJ (eds) Experiencing and managing emotions in the workplace. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 329–352

Demerouti E, Nachreiner F, Baker AB, Schaufeli WB (2001) The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol 86(3):499–512

Diefendorff JM, Gosserand RH (2003) Understanding the emotional labor process: a control theory perspective. J Organ Behav 24(8):945–959

Diefendorff JM, Croyle MH, Gosserand RH (2005) The dimensionality and antecedents of emotional labor strategies. J Vocat Behav 66(2):339–357

Douglas SP, Craig CS (2007) Collaborative and iterative translation: an alternative approach to back translation. J Int Mark 15(1):30–43

Elmadağ AB, Ellinger AE (2018) Alleviating job stress to improve service employee work affect: the influence of rewarding. Serv Bus 12(1):121–141

Fisk R, Grove S, Harris LC, Keeffe DA, Daunt KL, Russell-Bennett R, Wirtz J (2010) Customers behaving badly: a state of the art review, research agenda and implications for practitioners. J Serv Mark 24(6):417–429

Foreman SK, Money AH (1995) Internal marketing: concepts, measurement and application. J Mark Mange 11(8):755–768

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50

Garry T (2008) Affect and the role of corporate customer expertise within legal services. J Serv Mark 22(4):292–302

Gist ME, Mitchell TR (1992) Self-efficacy: a theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability. Acad Mange Rev 17(2):183–211

Gosserand RH, Diefendorff JM (2005) Emotional display rules and emotional labor: the moderating role of commitment. J Appl Psychol 90(6):1256–1264

Gountas S, Ewing MT, Gountas JI (2006) Testing airline passengers’ responses to flight attendants’ expressive displays: the effects of positive affect. J Bus Res 60(1):81–83

Grandey AA (2000) Emotional regulation in the workplace: a new way to conceptualize emotional labor. J Occup Health Psychol 5(1):95–110

Grandey AA (2003) When ‘the show must go on’: surface acting and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer-rated service delivery. Acad Mange J 46(1):86–96

Grandey AA, Dickter DN, Sin H (2004) The customer is not always right: customer aggression and emotion regulation of service employees. J Organ Behav 25(3):397–418

Grandey AA, Fisk GM, Steiner DD (2005) Must ‘service with a smile’ be stressful? the moderating role of personal control for American and French employees. J Appl Psychol 90(5):893–904

Grandey AA, Kern JH, Frone MR (2007) Verbal abuse from outsiders versus insiders: comparing frequency, impact on emotional exhaustion, and the role of emotional labor. J Occup Health Psychol 12(1):63–79

Gross JJ (1998) The emerging field of emotion regulation: an integrative review. Rev Gen Psychol 2(3):271–299

Groth M, Hennig-Thurau T, Walsh G (2009) Customer reactions to emotional labor: the roles of employee acting strategies and customer detection accuracy. Acad Mange J 52(5):958–974

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ (2010) Multivariate data analysis: a global perspective. Pearson Education, New York, NY

Harris LC, Daunt K (2013) Managing customer misbehavior: challenges and strategies. J Serv Mark 27(4):281–293

Harrison WD (1980) Role strain and burnout in child-protective service workers. Soc Serv Rev 54(1):31–44

Hennig-Thurau T, Groth M, Paul M, Gremler DD (2006) Are all smiles created equal? How emotional contagion and emotional labor affect service relationships. J Mark 70(3):58–73

Hobfoll SE (2001) The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl Psychol 50(3):337–369

Hochschild AR (1979) Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. Am J Sociol 85(3):551–575

Hochschild AR (1983) The managed heart: commercialization of human feeling. University of California Press, Berkley, CA

Hoffmann EA (2016) Emotions and emotional labor at worker-owned businesses: deep acting, surface acting, and genuine emotions. Sociol Q 57(1):152–173

Hogarty KY, Hines CV, Kromrey JD, Ferron JM, Mumford KR (2005) The quality of factor solutions in exploratory factor analysis: the influence of sample size, communality, and overdetermination. Educ Psychol Meas 65(2):202–226

Hollet-Haudebert S, Mulki JP, Fournier C (2011) Neglected burnout dimensions: effect of depersonalization and personal nonaccomplishment on organizational commitment of salespeople. J Personal Selling Sales Mange 31(4):411–428

Howard DJ, Gengler C (2001) Emotional contagion effects on product attitudes. J Consumer Research 28(2):189–201

Huang YW, Brown T (2016) How does customer orientation influence authentic emotional display? J Serv Mark 30(3):316–326

Hülsheger UR, Schewe AF (2011) On the costs and benefits of emotional labor: a meta-analysis of three decades of research. J Occup Health Psychol 16(3):361–389

Hur WM, Moon TW, Jung YS (2015) Customer response to employee emotional labor: the structural relationship between emotional labor, job satisfaction, and customer satisfaction. J Serv Mark 29(1):71–80

Hur WM, Moon T, Jun JK (2016a) The effect of workplace incivility on service employee creativity: the mediating role of emotional exhaustion and intrinsic motivation. J Serv Mark 30(3):302–315

Hur WM, Rhee SY, Ahn KH (2016b) Positive psychological capital and emotional labor in Korea: the job demands-resources approach. Int J Hum Resour Manage 27(5):477–500

Jackson SE, Schwab RL, Schuler RS (1986) Toward an understanding of the burnout phenomenon. J Appl Psychol 71(4):630–640

Jeon A (2016) The effect of pre-flight attendants’ emotional intelligence, emotional labor, and emotional exhaustion on commitment to customer service. Serv Bus 10(2):345–367

Johanson MM, Woods RH (2008) Recognizing the emotional element in service excellence. Cornell Hosp Q 49(3):310–316

Julian CC (2008) Emotional dissonance and customer service: an exploratory study. Serv Mark Q 29(3):1–23

Julian CC, Ramaseshan B (1994) The role of customer-contact personnel in the marketing of a retail bank′s services. Int J Retail Distrib Manage 22(5):29–34

Karatepe OM, Karadas G (2016) Service employees’ fit, work-family conflict, and work engagement. J Serv Mark 30(5):554–566

Keiser TC (1988) Strategies for enhancing services quality. J Serv Mark 2(3):65–70

Kiely JA (2005) Emotions in business-to-business service relationships. Serv Ind J 25(3):373–390

Kim HJ (2008) Hotel service providers’ emotional labor: the antecedents and effects on burnout. Int J Hosp Manage 27(2):151–161

Kim K, Baker MA (2020) The customer isn’t always right: the implications of illegitimate complaints. Cornell Hosp Q 61(2):113–127

Kim Y, Deci EL, Zuckerman M (2002) The development of the self-regulation of withholding negative emotions questionnaire. Educ Psychol Meas 62(2):316–336

Kim TT, Paek S, Choi CH, Lee G (2012) Frontline service employees’ customer-related social stressors, emotional exhaustion, and service recovery performance: customer orientation as a moderator. Serv Bus 6(4):503–526

Kim TT, Karatepe OM, Lee G (2018) Psychological contract breach and service innovation behavior: psychological capital as a mediator. Serv Bus 12(2):305–329

Kim JY, Lacey R, Kim HR, Suh JB (2019) How CSR serves as a preventive mechanism for coping with dysfunctional customer behavior. Serv Bus 13(4):671–694

Koku PS, Savas S (2016) Restaurant tipping and customers’ susceptibility to emotional contagion. J Serv Mark 30(7):762–772

Kristof AL (1996) Person-organization fit: an integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Personnel Psychol 49(1):1–49

Kruml SM, Geddes D (2000) Exploring the dimensions of emotional labor: the heart of Hochschild’s work. Manage Commun Q 14(1):8–49

Kumar Madupalli R, Poddar A (2014) Problematic customers and customer service employee retaliation. J Serv Mark 28(3):244–255

Lai HS, Hu HH, Chen ZYJ (2020) The effects of culture shock on foreign employees in the service industry. Serv Bus 14(3):361–385

Lee RT, Ashforth BE (1996) A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. J Appl Psychol 81(2):123–133

Lee C, An M, Noh Y (2015) The effects of emotional display rules on flight attendants’ emotional labor strategy, job burnout and performance. Serv Bus 9(3):409–425

Lewin JE, Sager JK (2009) An investigation of the influence of coping resources in salespersons’ emotional exhaustion. Ind Mark Mange 38(7):798–805

Li CY, Fang YH (2016) How online service recovery approaches bolster recovery performance? A multi-level perspective. Serv Bus 10(1):179–200

Low GS, Cravens DW, Grant K, Moncrief WC (2001) Antecedents and consequences of salesperson burnout. Eur J Mark 35(5/6):587–611

Lytle RS, Timmerman JE (2006) Service orientation and performance: an organizational perspective. J Serv Mark 20(2):136–214

Medler-Liraz H (2016) The role of service relationships in employees’ and customers’ emotional behavior, and customer-related outcomes. J Serv Mark 30(4):437–448

Morris JA, Feldman DC (1996) The dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of emotional labor. Acad Manage Rev 21(4):986–1010

Nasurdin AM, Ahmad NH, Tan CL (2015) Cultivating service-oriented citizenship behavior among hotel employees: the instrumental roles of training and compensation. Serv Bus 9(2):343–360

Papastylianou A, Kaila M, Polychronopoulos M (2009) Teachers’ burnout, depression, role ambiguity and conflict. Soc Psychol Educ 12(3):295–314

Picard K, Morin D, Cossette M (2018) Service with a smile: a source of emotional exhaustion or performance incentive in call-centre employees. Can J Admin Sci 35(2):214–227

Ping RA (1995) A parsimonious estimating technique for interaction and quadratic latent variables. J Mark Research 32(3):336–347

Poulston J (2008) Hospitality workplace problems and poor training: a close relationship. Int J Contem Hosp Manage 20(4):412–427

Pugh SD (2001) Service with a smile: emotional contagion in the service encounter. Acad Manage J 44(5):1018–1027

Raub S, Streit EM (2006) Realistic recruitment: an empirical study of the cruise industry. Int J Contem Hosp Manage 18(4):278–289

Rentsch JR, McEwen AH (2002) Comparing personality characteristics, values, and goals as antecedents of organizational attractiveness. Int J Select Assess 10(3):225–234

Rizzo JR, House RJ, Lirtzman SI (1970) Role conflict and ambiguity in complex organizations. Admin Sci Q 15(2):150–163

Rosenblat A, Stark L (2016) Algorithmic labor and information asymmetries: a case study of uber’s drivers. Int J Commun 10:3758–3784

Rutherford B, Boles J, Hamwi GA, Madupalli R, Rutherford L (2009) The role of the seven dimensions of job satisfaction in salesperson’s attitudes and behaviors. J Bus Res 62(11):1146–1151

Sager JK, Strutton HD, Johnson DA (2006) Core self-evaluations and salespeople. Psychol Mark 23(2):95–113

Sandiford PJ, Seymour D (2011) Reacting to the demands of service work: emotional resistance in the coaching inn company. Serv Ind J 31(8):1195–1217

Sawyerr OO, Srinivas S, Wang S (2009) Call center employee personality factors and service performance. J Serv Mark 23(5):301–317

Seger-Guttmann T, Medler-Liraz H (2016) Does emotional labor moderate customer participation and buying? Serv Ind J 36(7–8):356–373

Shani A, Uriely N, Reichel A, Ginsburg L (2014) Emotional labor in the hospitality industry: the influence of contextual factors. Int J Hosp Mange 37(February):150–158

Shanshan Q, Chao M (2017) When is emotional labor less detrimental to employee weil-being? The moderating effect of rewards and motivational forces of display rules. Am J Mange 17(7):64–78

Shih-Tse Wang E (2014) The effects of relationship bonds on emotional exhaustion and turnover intentions in frontline employees. J Serv Mark 28(4):319–330

Singh J, Goolsy JR, Rhoads GK (1994) Behavioral and psychological consequences of boundary spanning burnout for customer service representatives. J Mark Res 31(4):558–569

Spreitzer GM (1996) Social structural characteristics of psychological empowerment. Acad Mange J 39(2):483–504

Steinberg RJ (1999) Emotional labor in job evaluation: redesigning compensation practices. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 561(1):143–157

Taylor J (2014) Public service motivation, relational job design, and job satisfaction in local government. Public Admin 92(4):902–918

Terblanche NS (2016) Measuring word-of-mouth activity after a service encounter: are we measuring what customers communicate? Serv Bus 10(2):283–299

Tsai WC (2001) Determinants and consequences of employee displayed positive emotions. J Mange 27(4):497–512

Tsai WC, Huang YM (2002) Mechanisms linking employee affective delivery and customer behavioral intentions. J Appl Psychol 87(5):1001–1008

Van Maanen J, Kunda G (1989) Real feelings’: emotional expression and organizational culture. In: Staw BM, Cummings LL (eds) Research in organizational behaviour. JAI Press, Greenwich, pp 43–103

Walsh G, Hammes EK (2017) Do service scripts exacerbate job demand-induced customer perceived discrimination? J Serv Mark 31(4/5):471–479

Wang EST (2009) Displayed emotions to patronage intention: consumer response to contact personnel performance. Serv Ind J 29(3):317–329

Wang EST, Tsai BK, Chen TL, Chang SC (2012) The influence of emotions displayed and personal selling on customer behaviour intention. Serv Ind J 32(3):353–366

Wanous JP (1973) Effects of a realistic job preview on job acceptance, job attitudes, and job survival. J Appl Psychol 58(3):327–332

Wanous JP (1992) Organizational entry: recruitment, selection, orientation, and socialization of newcomers. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Boston, MA

Wharton AS, Erickson RI (1993) Mabaging emotions on the job and at home: understanding the consequences of multiple emotional roles. Acad Mange Rev 18(3):457–486

Wickham J, Collins G (2004) The call centre: a nursery for new forms of work organisation? Serv Ind J 24(1):1–18

Wright TA, Cropanzano R (1998) Emotional exhaustion as a predictor of job performance and voluntary turnover. J Appl Psychol 83(3):486–493

Yagil D, Medler-Liraz H (2019) The effect of customer social status and dissatisfaction on service performance. Serv Bus 13(1):153–169

Yoo JJ, Arnold TJ (2014) Customer orientation, engagement, and developing positive emotional labor. Serv Ind J 34(16):1272–1288

Zhang Y, Zhang L, Lei H, Yue Y, Zhu J (2016) Lagged effect of daily surface acting on subsequent day’s fatigue. Serv Ind J 36(15–16):809–826

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chung, M., Jang, YH. & Edelson, S.A. The path from role clarity to job satisfaction: natural acting and the moderating impact of perceived fairness of compensation in services. Serv Bus 15, 77–102 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-020-00434-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-020-00434-5