ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES

We employed a partnered research healthcare delivery redesign process to improve care for high-need, high-cost (HNHC) patients within the Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system.

METHODS

Health services researchers partnered with VA national and Palo Alto facility leadership and clinicians to: 1) analyze characteristics and utilization patterns of HNHC patients, 2) synthesize evidence about intensive management programs for HNHC patients, 3) conduct needs-assessment interviews with HNHC patients (n = 17) across medical, access, social, and mental health domains, 4) survey providers (n = 8) about care challenges for HNHC patients, and 5) design, implement, and evaluate a pilot Intensive Management Patient-Aligned Care Team (ImPACT) for a random sample of 150 patients.

RESULTS

HNHC patients accounted for over half (52 %) of VA facility patient costs. Most (94 %) had three or more chronic conditions, and 60 % had a mental health diagnosis. Formative data analyses and qualitative assessments revealed a need for intensive case management, care coordination, transitions navigation, and social support and services. The ImPACT multidisciplinary team developed care processes to meet these needs, including direct access to team members (including after-hours), chronic disease management protocols, case management, and rapid interventions in response to health changes or acute service use. Two-thirds of invited patients (n = 101) enrolled in ImPACT, 87 % of whom remained actively engaged at 9 months. ImPACT is now serving as a model for a national VA intensive management demonstration project.

CONCLUSIONS

Partnered research that incorporated population data analysis, evidence synthesis, and stakeholder needs assessments led to the successful redesign and implementation of services for HNHC patients. The rigorous design process and evaluation facilitated dissemination of the intervention within the VA healthcare system.

IMPACT STATEMENT

Employing partnered research to redesign care for high-need, high-cost patients may expedite development and dissemination of high-value, cost-saving interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Within the U.S. population, Medicaid-covered and Medicare-covered populations, and large integrated healthcare organizations such as the Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system, 5–10 % of patients account for approximately half of total healthcare spending.1–7 Interest in these high-need, high-cost (HNHC) patients has intensified in recent years, as healthcare systems and Accountable Care Organizations increasingly focus limited resources on high-risk patients to prevent the unnecessary use of costly services.8,9

To meet the needs of HNHC patients, many organizations are developing specialized intensive management programs, offering enhanced clinical access, care coordination, medication reconciliation, support during transitions from hospital to home, and referrals to social and community services.10–12 The evidence on these programs is mixed. Although some early innovative programs reported reductions in emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and costs,13–15 many of these were for-profit or employer-based programs. Studies of intensive management in urban and safety-net patient populations generally report more modest or neutral findings,16–18 although there are exceptions, such as uncontrolled observational studies of the Camden Coalition in Camden, New Jersey.19–21

One reason for the evidence shortage around intensive management programs is the difficulty of integrating complex organizational interventions and rigorous program evaluations. Robust evaluations may require staged interventions or randomization, long follow-up duration, and patient and staff surveys to determine effects, adding cost and time beyond the already expensive clinical efforts.21–23

Partnered research—collaboration between researchers, operational leaders, and clinicians—is a unique approach to program development that may facilitate rapid healthcare redesign and implementation, while allowing for rigorous evaluation and testing. The VA has a rich tradition of sponsoring intramural partnered research, dating back to the development of the Quality Enhancement Research Initiative in the 1990s,24 and these partnerships have been associated with substantial quality improvement achievements.25 This paper describes a partnership between health services researchers, operational leadership, and clinicians in the VA healthcare system that led to the successful design, implementation, and evaluation of a novel intensive management program for HNHC patients in the VA Palo Alto Health Care System

METHODS

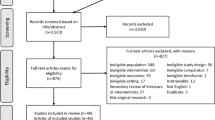

Table 1 describes the partnered research approach that we used to redesign care for HNHC patients. The collaboration emerged from shared interest in intensive management programs among national VA leadership (SK), and VA Palo Alto clinical leaders and health services researchers. The VA Palo Alto project core team included researchers (DZ, SA, JB) and facility leadership (SEO, Deputy Chief of Staff; JK, Chief of Medicine; and JC, Associate Chief of Staff for Ambulatory Care), and later expanded to include the ImPACT clinical team (JS, DH, KH, SS) and advisors from an established intensive management clinic at Stanford University. Our partnership incorporated many of the elements of a collaborative evaluation,26 including iterative dialogue among all partners. Partners maintained clearly delineated clinical and evaluation roles. Decisions were made by consensus when possible, with deferral of final decisions to facility leadership (for program decisions) and research leadership (for evaluation decisions). The core team met weekly during the first year of program development and implementation, and bi-weekly throughout the duration of the intervention pilot and evaluation.

Characterization of Target Patient Population

In response to facility leadership’s query, researchers identified high-cost patients using administrative records. For all patients who received care in fiscal year (FY) 2010, researchers identified the 5 % most costly patients (N = 3,135), excluding individuals who had a total length of stay > 182 days in order to focus on appropriate candidates for an outpatient intervention. For the remaining patients (n = 2,730), they assessed average FY2010 costs for inpatient, outpatient, pharmacy, and VA-sponsored contract care, frequency of costly acute care (emergency room visits and hospitalizations), and sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex). Chronic conditions that are the focus of quality improvement efforts and research within the VA24,27–29 were identified using ICD-9 codes that were documented at least once in an inpatient or outpatient encounter. Researchers presented descriptive statistics to the facility’s clinical leadership committee to inform program adoption and design.

Evidence Synthesis

To guide program development, researchers reviewed common elements of existing intensive management outpatient care programs. The review built on an existing evidence synthesis, prepared by the VA’s Evidence-Based Synthesis Program Coordinating Center.11 Researchers supplemented this with peer-reviewed and gray literature describing early innovations in intensive management,14,16,18,21–23,30–33 and with review articles describing healthcare delivery interventions for patients with complex chronic illnesses.34–36 The review incorporated key findings, study design, and implementation strategies,37 and was discussed with facility leadership to identify common elements of successful programs that would be viable and effective within the VA environment and at the local facility.

Needs Assessment of Target Patient Population

Facility leadership facilitated contact with HNHC patients who were then interviewed by clinical support staff. To guide interviews, researchers adapted a needs assessment tool for HNHC patients that is widely used by intensive management programs.38,39 Interviewers asked about four domains: medical neighborhood (e.g., access, care coordination), medical status (e.g., symptoms, treatment), social support (e.g., relationships, home environment), and self-management/mental health. Findings were synthesized by researchers and clinical partners to identify themes representing the target population’s most common needs, challenges, and goals. Themes were discussed at weekly meetings, and interviews were conducted until the team felt thematic saturation was achieved.

Engagement of Clinical Partners

Researchers developed a survey to solicit healthcare providers’ input about services that would most benefit their HNHC patients. An ImPACT team member administered the survey to primary care providers of target HNHC patients (N = 8). Providers were given a list of their HNHC patients who were eligible for the new program, and asked to rate (on a scale of 1 to 10) the value of specific services that were under consideration for the intervention. Researchers presented survey findings to the core team.

Intervention Design

Findings from each of the above steps informed the development of an intervention for HNHC patients: Intensive Management Patient-Aligned Care Team (ImPACT). Facility leadership sought to design a program that would build on existing facility resources, including the VA’s primary care medical home structure (Patient-Aligned Care Team, or PACT).40 Leadership and researchers collaborated on decisions about patient eligibility criteria, structure of the multidisciplinary clinical team, and program design and services. The intervention was iteratively refined in response to feedback from PACT physicians and nurses.

Program Implementation

Facility leadership decided to offer the ImPACT program to a random sample of 150 HNHC patients to refine procedures prior to dissemination and long-term budgetary commitment. The ImPACT clinical program was designated as a non-research quality improvement initiative by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board (IRB). For the program evaluation, researchers received IRB approval to take advantage of the natural experiment and evaluate the program’s effect on utilization and costs, with estimated 80 % power to detect a 20 % decline in costs among the 150 ImPACT patients compared to HNHC patients receiving only PACT care. In order to facilitate clinical management and evaluation, researchers and the clinical team developed a patient tracking system to monitor key information (i.e., patient goals, emergency department visits, hospitalizations, health status changes, frequency of contact).

Evaluation

Researchers developed an evaluation plan that would answer facility leadership questions about program effectiveness and sustainability, and contribute to the broader scientific literature on intensive management programs. Components included a program feasibility assessment, an implementation evaluation at 9 months (using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research),41 and analyses of changes in cost, healthcare utilization, and patient-centered outcomes (e.g., functional status, symptoms, patient activation, satisfaction with care) at 16 months (ensuring a minimum of 9 months follow-up for all enrollees).

Importantly, while research leadership participated in ImPACT core team meetings, there were research collaborators—a statistician, health economist, and data analyst—who did not interact with the clinical team to promote analytic impartiality.42 We report the results of our feasibility evaluation here, including an analysis of enrollment, engagement rates, and frequency of clinic interactions with patients. Analyses of data for the other evaluation components are in progress.

RESULTS

Characterization of Target Patient Population

Initial analyses confirmed that the 5 % highest cost patients accounted for approximately half (52 %) of total patient costs for the facility, slightly more than national VA estimates.7 For the population of 2,730 high-cost patients who were outpatients for over half of 2010, 67 % of costs were generated by inpatient care, 19 % by outpatient care, 6 % by pharmacy services, and 8 % by VA-sponsored contract care. Nearly half of inpatient costs (49 %) were for medical/surgical care, 16 % for behavioral/mental health care, and 14 % for long-term care. About half of outpatient costs (56 %) were for medical/surgical care and 19 % were for mental health care.

The mean (SD) age of HNHC patients was 63 (14) years, and 40 % were age 65 or older. Paralleling the VA patient population, 94 % of HNHC patients were male. The vast majority (92 %) had at least three chronic conditions, and 60 % had at least one mental health comorbidity. The most common conditions included hypertension (69 %), diabetes (65 %), lower back pain (30 %), ischemic heart disease (29 %), chronic renal failure (28 %), and cancer (26 %). The most common mental health conditions included depression (54 %), post-traumatic stress disorder (27 %), alcohol dependence/abuse (21 %), and substance use/abuse (18 %) (Online Appendix 1).

Hospitalization rates were extremely high among HNHC patients, with 90 %, 30 %, and 8 % of patients having at least one, three, or five admissions during the year of investigation, respectively. Similarly, for emergency department utilization, 28 % of patients had two to four visits, and 15 % had five or more visits. These utilization rates and patient characteristics helped guide the facility’s decisions about program adoption and design.

Evidence Synthesis

The literature review revealed a number of common services among intensive management programs across diverse settings (Box 1). Facility leadership selected services that would be of greatest additional value in the context of the existing VA patient-centered medical home. These included expanding access through a direct call line to clinic staff and after-hours access to a physician, better coordination of specialty care services, and case management to enhance quality of life and strengthen social support and stability. Other services, such as intensive mental health care, home-based primary care, and palliative care, were already well-established within the facility, and were made available to ImPACT patients via referral.

Needs Assessment of Target Patient Population

Interviews with HNHC patients (n = 17) revealed common needs that would be amenable to an intensive management intervention focusing on access, care coordination, and social support and services (Table 2).

Engagement of Clinical Partners

Primary care providers rated all of the proposed services for the new intensive management program highly (all had a mean rating ≥ 8 out of 10): improve chronic disease management, decrease utilization of avoidable/unnecessary care, improve patient quality of life, reconcile medications, provide social support, facilitate transitions from hospital to home, improve pain control and manage pain medications, enhance patient engagement and adherence, provide after-hours telephone consultations with a familiar care team member, offer recreational activities, facilitate access to care, evaluate a patient’s home environment, and coordinate specialty care. All of these elements were integrated into the design of ImPACT.

ImPACT Implementation

The ImPACT program is described in Box 2; program materials and procedures are available in the ImPACT Toolkit (Online Appendix 3). Patients were eligible for the program if their total VA healthcare costs were in the top 5 % between 1 October 2011 and 30 June 2012, or if their risk for one-year hospitalization was in the top 5 % (using a VA risk-prediction algorithm).43 Patients were excluded if they were already enrolled in another intensive management program (e.g., mental health intensive case management, home-based primary care, palliative care) or if they were hospitalized or in long-term care for over half of the baseline period. Selected patients were approached during hospitalizations, emergency department visits, before or after clinical appointments, and by letter and telephone. If patients were interested in receiving ImPACT care, the team completed a comprehensive intake. The intake included a medical chart review and an in-person interview using both structured tools and open-ended questions to assess patients’ medical and psychosocial challenges, and to elicit health-related goals and priorities. The initial visit(s) also included assessments of function, frailty, cognitive impairment, social support, advance directives, medication adherence, and patient activation.

The ImPACT team then developed a patient-centered, goal-based care plan, including referrals to appropriate clinical, social, and community-based services. The team used the researcher-developed patient tracker to monitor key events (e.g., recent emergency department visits and hospitalizations, upcoming appointments), document case management goals and progress, and identify individuals with unstable health status or social circumstances. High acuity patients were discussed in a weekly huddle, and contacted as frequently as necessary (e.g., daily, weekly) to facilitate stabilization. When patients were hospitalized, ImPACT team members interacted with inpatient providers to identify necessary services and followed up within one to two days of discharge. Lower acuity patients were also followed up at regular, but longer intervals (e.g., monthly), with outreach to patients who were not actively engaged with services.

Feasibility Evaluation

Two-thirds of invited patients (n = 101) enrolled in ImPACT within the first 7 months of the program (1 February 2013 to 31 August 2013) and 87 % of participants remained actively engaged in the program at 9 months. Engaged and non-engaged patients did not vary significantly on key sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, with the exception that non-engaged patients were more likely to reside in a rural area (15 % vs. 4 %, p < 0.05) and had higher rates of schizophrenia (13 % vs. 2 %, p < 0.01). During months 9 to 12 of the program, patients had an average of five ImPACT encounters (documented in-person or telephone care visits), and the ten highest-utilizers had ten to 21 encounters (mean (SD)=14 (3)). A full evaluation of ImPACT’s implementation and its effect on healthcare utilization, cost, and patient-centered outcomes is in progress; however, early observations about the program’s feasibility, implementation, and reception helped inform the development of a national VA intensive management demonstration project, Patient-Aligned Care Team-Intensive Management (PACT-IM). The VA Office of Primary Care funded PACT-IM programs at five VA facilities, and is supporting a National Evaluation Center to rigorously study the programs’ impact on healthcare utilization and costs for HNHC patients.

DISCUSSION

This paper describes a successful approach to partnered research in the design, implementation, and evaluation of an intensive management intervention for HNHC patients. The program’s services were informed by patients’ characteristics, utilization patterns, needs, and perceived challenges. Iterative dialogue among researchers and operational partners strengthened the intervention’s design and feasibility. The resulting program was implemented rapidly and successfully with high levels of engagement, and is now serving as a model for a national multi-site VA intensive management demonstration project.

Partnered research facilitated ImPACT’s development in several ways. First, in response to leadership’s request, researchers characterized the facility’s HNHC patients and helped identify individuals who would likely benefit from intensive management. The collaborative literature review, patient needs assessment, and provider survey guided interventional development. All of these steps were conducted systematically and with a level of rigor (e.g., use of structured assessments and validated measures, assessment of evidence quality) that is typical of health services research, but not always feasible within a quality improvement environment. These pre-implementation efforts not only strengthened the intervention, they also illuminated the cultural and organizational context for researchers,44 thereby informing the evaluation design. Similarly, weekly communication between the ImPACT clinical team, facility leadership, and researchers facilitated trouble-shooting and rapid modifications to the intervention and evaluation plan as needed.

Collaboration with facility leadership was also critical to the design of a rigorous evaluation. Facility leadership wanted to ensure that the program’s effects would be measurable in order to support decisions about program continuation. They therefore supported program implementation for a random sample of patients. While piloting on a small subset before dissemination is common, random selection for such initial interventional development is rare in quality improvement.45 However, this technique is quite effective for understanding causal inference, and researchers were able to design a robust study of the program’s effect on healthcare utilization and costs. Furthermore, the partnered approach permitted rapid design and implementation of the program and its evaluation, so that we were able to enroll a random sample of patients within 12 months of program conception. As a result, the ImPACT program is now informing plans for a multi-site VA intensive management demonstration project, with random enrollment of high-risk patients at five facilities.

Partnered research also presented unique challenges. For researchers, the priorities of facility leadership and clinicians did not always align with the optimal research design, resulting in a need for real world evaluation techniques.46 For example, facility leadership chose not to survey comparison group patients in order to minimize burden to individuals who were not receiving intensive management. Researchers therefore had to limit the controlled evaluation to electronic health record and administrative data. There were also instances where the objectives for implementation and evaluation differed. For example, early in the intervention, there was tension about whether to focus ImPACT resources on patients whom the clinical team felt would benefit most, versus maintain a focus on all patients assigned to ImPACT under the intent-to-treat design. Weekly meetings between clinicians, facility leadership, and researchers (importantly, guided by a culture of respect for the expertise of all parties), provided an opportunity to discuss the needs of all stakeholders and resolve conflicts.

Additional challenges arose due to tension between the time needed for rigorous research and the time frame in which definitive results were desired for operational purposes. This tension was heightened because ImPACT is a resource-intensive intervention, and the facility will likely require evidence of safety and cost savings to sustain the program as designed. Relatedly, for the clinical team, the research partnership generated pressure to achieve positive results quickly. This was especially challenging in the context of an intervention that aims to improve health behaviors, prevent unnecessary utilization, and bend the cost curve for HNHC patients—all of which take time.

Finally, the VA’s history of intramural research likely contributed to the success of this partnered effort. While many of the elements of this effort could be adopted by academic-operational partners, the VA system and culture encourages collaborations between health services researchers and operational partners that produce high-impact research and policy.24

The ImPACT program represents a successful example of how partnered research can facilitate simultaneous care redesign and robust evaluation. Employing this design for high-risk, high-utilizing patient populations may expedite the development and dissemination of high-value interventions that transform care for complex and costly patients.

REFERENCES

Cohen S, Yu W. AHRQ Statistical Brief #354: The concentration and persistance in the level of health expenditures over time: Estimates for the US population, 2008-2009. 2012. http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st354/stat354.pdf. 8/29/14.

Mann C. Medicaid and CHIP: On the Road to Reform. Alliance for Health Reform/Kaiser Family Foundation. 2011. www.allhealth.org/briefingmaterials/KFFAlliance_FINAL-1971.ppt. 8/29/14.

Joynt K, Gawande AA, Orav E, Jha A. Contribution of preventable acute care spending to total spending for high-cost medicare patients. JAMA. 2013;309(24):2572–2578.

Conwell LJ, Cohen JW. AHRQ Statistical Brief #73: Characteristics of persons with high medical expenditures in the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population, 2002. 2005. http://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/st73/stat73.pdf. 8/29/14.

Sommers A, Cohen M. Medicaid's High Cost Enrollees: How Much Do They Drive Program Spending? Kaiser Commission for Medicaid and the Uninsured. D.C.: Washington; 2006.

Coughlin TA, Long SK. Health care spending and service use among high-cost Medicaid beneficiaries, 2002–2004. Inquiry Journal. 2009;46(4):405–17.

Zulman DM, Yoon J, Cohen DM, Wagner TH, Ritchie C, Asch SM. Multimorbidity and health care utilization among high-cost patients: Implications for care coordination. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(1):S123.

Silow-Carroll S, Edwards JN. Early Adopters of the Accountable Care Model: A Field Report on Improvements in Health Care Delivery. The Commonwealth Fund; New York, NY; 2013.

Hasselman D. Super-Utilizer Summit: Common Themes from Innovative Complex Care Management Programs. Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc. Hamilton, N.J. 2013.

Yee T, Lechner A, Carrier E. High-Intensity Primary Care: Lessons for Physician and Patient Engagment. National Institute for Health Care Reform. 2012;9.

Peterson D, Helfand M, Humphrey L, Christensen V, Carson S. Evidence Brief: Effectiveness of Intensive Primary Care Programs, VA-ESP Project #09-199; 2012.

Bodenheimer T. Strategies to Reduce Costs and Improve Care for High-Utilizing Medicaid Patients: Reflections on Pioneering Programs. Center for Health Care Strategies, Inc. 2013.

Reuben DB. Physicians in supporting roles in chronic disease care: The CareMore model. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(1):158–60.

Blash L, Chapman S, Dower C. The Special Care Center - A joint venture to address chronic disease. 2011. http://www.futurehealth.ucsf.edu/content/29/2010-11_the_special_care_center_a_joint_venture_to_address_chronic_disease.pdf. 8/29/14.

Milstein A, Kothari P. Are higher-value care models replicable? Health Affairs Blog. 2009. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2009/10/20/are-higher-value-care-models-replicable/. 8/29/14.

Shumway M, Boccellari A, O'Brien K, Okin RL. Cost-effectiveness of clinical case management for ED frequent users: Results of a randomized trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(2):155–64.

Sledge WH, Brown KE, Levine JM, Fiellin DA, Chawarski M, White WD, O'Connor PG. A randomized trial of primary intensive care to reduce hospital admissions in patients with high utilization of inpatient services. Disease Management. 2006;9(6):328–38.

Bell J, Mancuso D, Krupski T, Joesch JM, Atkins DC, Court B, West II, Roy-Byrne P. A randomized controlled trial of King County Care Partners’ Rethinking Care Intervention: Health and social outcomes up to two years post-randomization. 2012. http://www.chcs.org/media/RTC_Evaluation_TECHNICAL_REPORT_FINAL_3_15_12a.pdf. 8/29/14.

Brenner J. Reforming Camden's health care system—one patient at a time. Prescriptions for Excellence in Health Care. 2009;5:1–3.

Gawande A. The hot spotters: Can we lower medical costs by giving the neediest patients better care? The New Yorker; 2011.

Green SR, Singh V, O'Byrne W. Hope for New Jersey's city hospitals: The Camden Initiative. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2010;7:1d.

Raven MC, Doran KM, Kostrowski S, Gillespie CC, Elbel BD. An intervention to improve care and reduce costs for high-risk patients with frequent hospital admissions: A pilot study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:270.

Dorr DA, Wilcox A, Burns L, Brunker CP, Narus SP, Clayton PD. Implementing a multidisease chronic care model in primary care using people and technology. Dis Manag. 2006;9(1):1–15.

Demakis JG, McQueen L, Kizer KW, Feussner JR. Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI): A collaboration between research and clinical practice. Med Care. 2000;38(6 Suppl 1):I17–25.

Oliver A. Public-sector health-care reforms that work? A case study of the U.S. Veterans Health Administration. Lancet. 2008;371(9619):1211–3.

O'Sullivan RG. Collaborative evaluation within a framework of stakeholder-oriented evaluation approaches. Eval Program Plann. 2012;35(4):518–22.

Yoon J, Scott J, Phibbs CS, Wagner TH. Recent trends in Veterans Affairs chronic condition spending. Popul Health Manag. 2011;14(6):293–8.

Yu W, Ravelo A, Wagner TH, Phibbs CS, Bhandari A, Chen S, Barnett PG. Prevalence and costs of chronic conditions in the VA health care system. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60(3 Suppl):146S–167S.

Yoon J, Zulman D, Scott JY, Maciejewski ML. Costs Associated With Multimorbidity Among VA Patients. Med Care. 2014;52(Suppl 3):S31–6.

Dorr D, Wilcox AB, Brunker CP, Burdon RE, Donnelly SM. The effect of technology-supported, multidisease care management on the mortality and hospitalization of seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(12):2195–202.

Brown KE, Levine JM, Fiellin DA, O'Connor P, Sledge WH. Primary intensive care: Pilot study of a primary care-based intervention for high-utilizing patients. Dis Manag. 2005;8(3):169–77.

Lessler DS, Krupski A, Cristofalo M. King County Care Partners: A Community-Based Chronic Care Management System for Medicaid Clients with Co-Occurring Medical, Mental, and Substance Abuse Disorders. Comprehensive Care Coordination for Chronically III Adults: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2011:339-348.

Okin RL, Boccellari A, Azocar F, Shumway M, O'Brien K, Gelb A, Kohn M, Harding P, Wachsmuth C. The effects of clinical case management on hospital service use among ED frequent users. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18(5):603–8.

Brown RS, Peikes D, Peterson G, Schore J, Razafindrakoto CM. Six features of Medicare coordinated care demonstration programs that cut hospital admissions of high-risk patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(6):1156–66.

Boult C, Murphy EK. New models of comprehensive health care for people with chronic conditions. In: IOM, ed. Living Well with Chronic Illness: A Call for Public Action. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press; 2012:285-318.

Smith S, Soubhi H, Fortin M, Hudon C, O'Dowd T. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012(1469-493X).

Shekelle PG, Pronovost PJ, Wachter RM, McDonald KM, Schoelles K, Dy SM, Shojania K, Reston JT, Adams AS, Angood PB, Bates DW, Bickman L, Carayon P, Donaldson L, Duan N, Farley DO, Greenhalgh T, Haughom JL, Lake E, Lilford R, Lohr KN, Meyer GS, Miller MR, Neuhauser DV, Ryan G, Saint S, Shortell SM, Stevens DP, Walshe K. The Top Patient Safety Strategies That Can Be Encouraged for Adoption Now. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2013;158(5_Part_2):365-368.

California Healthcare Foundation, California Quality Collaborative. Complex Care Management Toolkit. 2012. http://www.calquality.org/storage/documents/cqc_complexcaremanagement_toolkit_final.pdf. 8/29/14.

Humboldt IPA Priority Care. Domain Assessment Tool. 2011. http://www.calquality.org/programs/clinicalcare/meteor/documents/1.2.2Humboldt_DomainsScoringLevels.pdf. 8/29/14.

Rosland AM, Nelson K, Sun H, Dolan ED, Maynard C, Bryson C, Stark R, Shear JM, Kerr E, Fihn SD, Schectman G. The patient-centered medical home in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(7):e263–72.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

Fitzpatrick JL. Commentary–collaborative evaluation within the larger evaluation context. Eval Program Plann. 2012;35(4):558–63.

Wang L, Porter B, Maynard C, Evans G, Bryson C, Sun H, Gupta I, Lowy E, McDonell M, Frisbee K, Nielson C, Kirkland F, Fihn SD. Predicting risk of hospitalization or death among patients receiving primary care in the Veterans Health Administration. Med Care. 2013;51(4):368–73.

Rodriguez-Campos L. Advances in collaborative evaluation. Eval Program Plann. 2012;35(4):523–8.

Perneger T. Ten reasons to conduct a randomized study in quality improvement. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006;18(6):395–6.

Bamberger JM, Rugh J, Mabry LS. RealWorld Evaluation: Working Under Budget, Time, Data, and Political Constraints, 2nd edition. SAGE Publications; 2011

Acknowledgements

Contributors

Authors would like to acknowledge Drs. Ian Tong and James Hallenbeck, Ms. Kalkidan Asrat, Ms. Lien Nguyen, and Ms. Jessica Radmilovic for their contributions to ImPACT’s design and implementation; Drs. Alan Glaseroff and Ann Lindsay from Stanford Coordinated Care for serving as clinical advisors to the ImPACT program; Danielle Cohen, Valerie Meausoone, and Cindie Slightam for data management and program evaluation support; and Ava Wong and Cindie Slightam for assistance with manuscript preparation. VA Palo Alto data acquisition and analysis was supported by Robert Chang, Robert King, Chi Pham, Lakshmi Ananth, and the Veterans Affairs Women’s Health Evaluation Initiative. Views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Funders

ImPACT program development and implementation was supported by the VA Office of Specialty Care Transformation (Specialty/Surgical Care Neighborhood Team Based Model Pilot Program). ImPACT program evaluation was supported by VA HSR&D (PPO 13-117). Dr. Zulman is supported by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award (CDA 12-173). Dr. Shaw is supported in part by VA Office of Academic Affairs and HSR&D funds. Dr. Breland is supported by the VA Office of Affiliations and VA HSR&D Service in conjunction with a VA HSR&D Advanced Fellowship Program.

Prior Presentations

None.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zulman, D.M., Ezeji-Okoye, S.C., Shaw, J.G. et al. Partnered Research in Healthcare Delivery Redesign for High-Need, High-Cost Patients: Development and Feasibility of an Intensive Management Patient-Aligned Care Team (ImPACT). J GEN INTERN MED 29 (Suppl 4), 861–869 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3022-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3022-7