Abstract

Parental sacrifice is an important feature of Chinese socialization. According to Walsh’s family resilience framework, perceived parental sacrifice serves as a familial protective factor that enhances adolescent positive development in the context of adversity and economic hardship. Based on a sample of 716 Chinese adolescents experiencing economic disadvantage in Hong Kong, this study examined the main and interaction effects of perceived paternal and maternal sacrifice on adolescent developmental outcomes (indexed by self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy) in Chinese families. We also examined the differences between paternal and maternal sacrifice perceived by adolescents. Results showed that adolescents perceived maternal sacrifice to be stronger than paternal sacrifice. Moreover, there were main and interaction effects of perceived paternal sacrifice and maternal sacrifice on adolescents’ self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy. When paternal sacrifice was at higher levels, maternal sacrifice positively predicted adolescents’ self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy. However, when paternal sacrifice was at lower levels, the influence of maternal sacrifice on adolescent self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy became non-significant. The study underscored the importance of paternal and maternal sacrifice and illustrated their interaction in shaping the developmental outcomes of economically disadvantaged adolescents. The theoretical and practical implications for family intervention work were discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Family poverty is a growing concern in the global and Chinese contexts. The family investment model (Conger and Donnellan 2007) asserts that poor families suffer from material deprivation that may restrict parental investment for their offspring, resulting in impairment of cognitive and psychosocial development in children and adolescents (Barajas et al. 2008). The family stress model also proposes that poverty hampers adolescent positive development via inadequate and harsh parenting (Conger and Donnellan 2007). However, research on family resilience (e.g., Walsh 2016) shows that economically disadvantaged parents do invest for the future development of their children, though the investment may require the parents to sacrifice their own needs (Leung and Shek 2011a). With respect to the Chinese parents, parental sacrifice has been regarded as a special feature of Chinese parenthood (Lam 2005). Unfortunately, there is a dearth of research on examining the influence of parental sacrifice on adolescent developmental outcomes in Chinese families (Leung and Shek 2015). Moreover, there are several unanswered questions in this field: Do fathers and mothers sacrifice equally from the eyes of the adolescents? Will paternal sacrifice interact with maternal sacrifice to influence adolescent development? Against this background, this study attempted to examine the main and interactive effects of perceived paternal and maternal sacrifice on adolescent developmental outcomes (indexed by self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy) in Chinese families. The difference between paternal and maternal sacrifice perceived by adolescents was also assessed. The findings may provide important insights for researchers, family practitioners and youth counselors to understand the family dynamics in poor Chinese families, which helps for the development of effective intervention strategies in building adolescents’ positive developmental outcomes in poor families.

Parental Sacrifice and Adolescent Development

Parental sacrifice is a family process in which parents fulfill the developmental needs of their children at the expense of satisfying their personal needs (Leung and Shek 2011a). However, there is a need to differentiate parental investment and parental sacrifice. While parental investment emphasizes the allocation of family resources for children’s development, parental sacrifice focuses on the parental attempt to satisfy their children’s needs at the expense of their own needs. While the former stresses on “what is given out from the parents to their children”, the latter emphasizes “what is given up by the parents for their children” (Leung and Shek 2016). By sacrificing the fulfilment of their own needs, parents invest family resources for their children’s future success.

Instead of adopting a pathological perspective that regards poor families as deficient and problematic, we employed Walsh’s family resilience framework (Walsh 2016) in this study to examine the family attributes that influence adolescent developmental outcomes. Walsh (2016) suggested that family resources and mutual connectedness within the families help the family members face adversity and hardship. Theoretically speaking, parental sacrifice promotes psychosocial development and wellbeing of adolescents through three mechanisms. First, parental sacrifice conveys parental love, commitment and subordination of one’s own interests for their offspring. Adolescents who feel indebted to parental sacrifice would excel and behave well to reciprocate their parents (Leung and Shek 2013a, 2013b). Second, parental sacrifice embodies a positive parent-child relationship that entails mutual trust and responsiveness and such relationship promotes adolescent psychosocial wellbeing (Laible and Carlo 2004). Third, by sacrificing the parents’ own needs, the resources that parents allocate to their adolescents promote their children’s cognitive and psychosocial development (Conger and Donnellan 2007). This is especially important for economically disadvantaged families as the material and financial resources are scarce. Previous studies have shown that parental sacrifice serves as a familial protective factor that enhances adolescent positive development in Chinese families experiencing economic disadvantage in Hong Kong (Leung and Shek 2013a, 2013b).

It is noteworthy that many related family studies did not differentiate the relative contributions of fathers and mothers, although fathers and mothers play different roles in the family. According to Bem (1974), mothers play a more responsible role on child rearing and daily family management, whereas fathers are the main income providers of the family. This contention is exemplified by the Chinese cultural belief of “nan zhu wai, nu zhu nei” (men manage things outside the family; women manage things inside). As such, adolescents may perceive more maternal sacrifice than paternal sacrifice as they identify their mothers’ support, care and responsiveness more easily than their fathers’ (Collins and Russell 1991). Empirically, it was found that adolescents perceived significantly more maternal sacrifice than paternal sacrifice in economically disadvantaged families (Leung and Shek 2012). However, as the existing findings are tentative in nature, we need to replicate the findings.

Interactive Effects between Paternal and Maternal Sacrifice

In a family system, one subsystem would interact with another subsystem to influence adolescent development (Cox and Paley 1997; Minuchin 1985). Theoretically, paternal sacrifice interacts with maternal sacrifice to affect adolescent development. When both paternal and maternal sacrifice are at higher levels, adolescents may sense their parents’ commitment in nurturing and providing resources for their development. The family supportive atmosphere as well as filial obligations to reciprocate their parents’ sacrifice may then promote adolescent psychosocial development (Leung and Shek 2013b; Yeh and Yang 1997). On the contrary, lower levels of paternal and maternal sacrifice may imply low commitment or failure of parents in nurturing their adolescents, which may result in poorer adolescent psychosocial development. When there are low levels of paternal sacrifice but high levels of maternal sacrifice (i.e., mothers attempt to create a nurturing environment for their children through their sacrifice but fathers do not), the family resources may not be adequate to support adolescent development because of low paternal commitment. Similarly, when there are high levels of paternal sacrifice but low levels of maternal sacrifice, adolescents exhibit lower levels of psychosocial developmental outcomes because they perceive the lack of maternal commitment towards their development. Moreover, discrepancies between paternal sacrifice and maternal sacrifice may imply a disagreement on the allocation of family resources between fathers and mothers, which may result in family conflicts and tension that in turn affect adolescent development (Olson et al. 1983).

Empirically, the existing literature shows that paternal behavior interacted with maternal behavior to influence adolescent development. Forehand and Nousiainen (1993) found that paternal acceptance moderated the effect of maternal acceptance on adolescent cognitive competence. Maternal acceptance positively predicted adolescent cognitive competence if fathers had higher levels of paternal acceptance, whereas the influence of maternal acceptance on adolescent cognitive competence was negative when fathers had lower levels of paternal acceptance. Similarly, Laible and Carlo (2004) found that paternal support interacted with maternal support to influence adolescent sympathy. Hence, it is interesting to examine whether paternal sacrifice interacts with maternal sacrifice to influence adolescent psychosocial development.

Roles of Adolescent Gender in the Effects

Previous studies showed equivocal findings on the differences between adolescent boys and girls in terms of the main effects of parental socialization on adolescent development. While some studies showed that adolescent girls had stronger attachment towards their parents and were more susceptible to the influence of parental affection than did adolescent boys (Linver and Silverberg 1997; Plunkett et al. 2007), there were other studies showing that the influence of parental support on adolescent development did not differ between boys and girls (Rueger et al. 2010; Wang and Eccles 2012). In the Chinese culture, parents are obliged to sacrifice their personal interests for the welfare and glory of the family (Yeh and Yang 1997), and contribute the best to the development of their children, regardless of the adolescent gender. Hence, we hypothesized that there would not be any differences between adolescent boys and girls in terms of the main and interaction effects of parental sacrifice on adolescent developmental outcomes.

Adolescent Developmental Outcomes

As far as adolescent positive development was concerned, three adolescent developmental outcomes were examined in the current study: self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy. Self-identity is the one’s subjective conception of oneself (Tsang et al. 2012). According to Erikson’s (1968) psychosocial theory of personality, a clear and positive self-identity is an essential element for one’s interpretations and pursuit of purposes and directions of life (Berzonsky 1994). Self-determination is one’s capacity to choose and make rational choices for one’s actions (Deci & Ryan 1985). It is the determinant for one’s motivation and sense of mastery over the environment (Deci and Ryan 2000). Self-efficacy is one’s beliefs in one’s own capacities to execute designated tasks and functions (Bandura 1997). It is crucial for goal formation, self-appraisal, motivation and achievement (Luszczynska et al. 2005). These developmental outcomes are vital for adolescents to meet the challenges of poverty, build up their self-confidence, set up life goals and motivate to excel (Bradley and Corwyn 2002; Wyman 2003).

The Current Study

This study attempted to examine the difference between paternal and maternal sacrifice from the perceptions of adolescents, and the direct and interactive effects of perceived paternal and maternal sacrifice in influencing adolescent developmental outcomes (indexed by self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy) in poor Chinese families. There were four research questions:

-

Research Question 1: Is there any difference between paternal and maternal sacrifice perceived by poor Chinese adolescents? Based on the sex-role theory (Bem 1974) that mothers take up the child-rearing roles and are more responsive to the needs of their children (Leung and Shek 2012), it was hypothesized that adolescents would perceive stronger maternal sacrifice than paternal sacrifice (Hypothesis 1).

-

Research Question 2: Do paternal and maternal sacrifice influence adolescent developmental outcomes (indexed by self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy) in poor Chinese families? As paternal and maternal sacrifices represent parental love, commitment and investment that enhance adolescent positive development (Leung and Shek 2013a, 2013b), it was hypothesized paternal and maternal sacrifice would positively influence adolescent self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy respectively (Hypotheses 2a – 2f).

-

Research Question 3: Does paternal sacrifice interact with maternal sacrifice to influence adolescent developmental outcomes (indexed by self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy) of poor Chinese adolescents? Based on the previous studies (Forehand and Nousiainen 1993; Laible and Carlo 2004) that paternal parenting moderated the prediction of maternal parenting on adolescent behaviors and previous observation that paternal sacrifice had stronger influences on adolescent development (Leung and Shek 2013a, 2013b), it was hypothesized that perceived paternal sacrifice would interact with maternal sacrifice in influencing developmental outcomes (self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy) of poor Chinese adolescents (Hypotheses 3a, 3b and 3c). Specifically, maternal sacrifice would be related to adolescent developmental outcomes under a high level than a low level of paternal sacrifice.

-

Research Question 4: Does adolescent gender moderate the main and interaction effects of paternal and maternal sacrifice on developmental outcomes of economically disadvantaged Chinese adolescents? Based on previous studies (e.g., Leung and Shek 2013b; Yeh and Yang 1997), we expected that adolescent gender would not moderate the main and interaction effects of paternal and maternal sacrifice on adolescent developmental outcomes.

Method

Participants and Procedures

As a complete list of economically disadvantaged families was unavailable in Hong Kong, we used stratified cluster sampling (Rubin and Babbie 2017) to recruit respondents from secondary schools, with school banding as the stratifying factor. All secondary schools across Hong Kong were included in the sampling frame. We sent invitation letters to the selected schools, and finally 12 secondary schools joined the study. We invited Secondary 1 and 2 (Grade 7 and 8) students experiencing economic disadvantage to voluntarily participate in the study. As school students commonly were not sure of their monthly household income, we used recipients of Comprehensive Social Security Assistance (CSSA), Full Textbook Allowance (TBA), and the Low-income Working Family Allowance (LIFA) as the screening criteria to identify the adolescent sample experiencing economic disadvantage. CSSA is a means-tested public assistance scheme provided by the Hong Kong Government for individuals and families who are financially insufficient to meet their essential needs. The TBA is also a means-tested financial subsidy for school students whose adjusted family income is considered as a low level. This is a common screening criterion for poor families who do not apply for CSSA (Shek 2005). The LIFA is a new means-tested scheme to provide financial aids to the poor working families. In case the adolescents responded positively to at least one of the schemes, they belonged to the economically disadvantaged group.

Data collection was taken in secondary schools. Informed consent from the parents and adolescents were sought. The researcher and/or trained research assistants introduced the purpose of study, procedures of data collection, rights to voluntarily participate and withdraw from the study to the adolescents. The adolescents filled out a questionnaire with the measures of perceived paternal and maternal sacrifice, self-identity, self-efficacy, self-determination and demographic characteristics. We gave the participants adequate time to complete the questionnaires, which lasted approximately 20 min. In total, 716 adolescents experiencing economic disadvantage joined the study. The study was approved and monitored by the Human Subjects Ethics Sub-committee of an internationally recognized university, which met the ethical standard of human research.

There were 365 male (51.0%) and 349 female (48.7%) respondents. The mean age of the adolescents was 13.22 (SD = 0.98). The participants included 417 adolescents (58.2%) in Secondary 1 (Grade 7) and 298 (41.6%) adolescents in Secondary 2 (Grade 8). There was one secondary school that only recruited students from Secondary 1 to join the study, contributing to an uneven distribution of students between grades. Majority of students were born in Hong Kong (n = 502, 70.1%) while 209 students (29.2%) were immigrants from mainland China. 217 adolescents (30.3%) came from non-intact families (family with second marriage, divorced, separated and widowed families).

Measurements

Parental Sacrifice

Chinese Paternal/Maternal Sacrifice Scale (PSA/MSA). Based on the qualitative findings of focus groups of Chinese parents and adolescents and the survey of literature on family capital (Coleman 1990) and family investment (Conger and Donnellan 2007), Leung and Shek (2011a) developed the PSA and MSA to assess paternal and maternal sacrifice respectively. The scale showed good psychometric properties (Leung and Shek 2011b; Leung et al. 2015). All items were rated on a 6-point Likert indicator measurement (1 = “Strongly Disagree”, 6 = “Strongly Agree”). A sample item is “My father/mother changes his/her habits to fit my educational needs”. The mean scores of the PSA and MSA were used to assess the degree of paternal and maternal sacrifice, with higher scores indicate higher levels of paternal and maternal sacrifice. Both PSA and MSA showed excellent internal consistencies in the study (PSA: α = .96; MSA: α = .95).

Adolescent Developmental Outcomes

Chinese Positive Youth Development Scale (CPYDS). Based on the conceptual framework of positive youth development developed by Catalano et al. (2002), Shek et al. (2007) developed the CPYDS to assess the competencies of adolescents in the Chinese communities. Three subscales were employed in the study: 1) Clear and Positive Identity Subscale (CPI). Based on a survey of literature (e.g., Meeus 1996), the CPI was developed to assess adolescents’ positive identity. A 3-item short form was used in the study. A sample item of the CPI is “I can do things as good as others”. 2) Self-determination Subscale (SDE). Based on the review of the literature (e.g., Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2000), the SDE was developed to assess adolescents’ readiness of decision-making, autonomy and self-advocacy. A 3-item short form was used in the study. A sample item is “I am confident about my decisions”. 3) Self-efficacy Subscale (SE). The SE was modelled after the Chinese version of Mastery Scale (Shek 2004). A 2-item short-form, “I believe things happening in my life are mostly determined by me” and “I can finish almost everything that I am determined to do”, were used in the study. All items of CPI, SDE and SE were rated on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = “Strongly Disagree”, 6 = “Strongly Agree”). The mean scores of the CPI, SDE and SE were used to indicate the levels of self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy respectively, with high scores indicating stronger developmental attributes. The three subscales showed acceptable internal consistencies in the study (CPI: α = .83; SDE: α = .80; SE: α = .77).

Data Analyses

To address Research Question 1, we performed a paired t-test to assess the difference between perceived paternal and maternal sacrifice. To examine the main effects and interaction effects proposed in Research Questions 2 and 3, we conducted hierarchical multiple regression analyses. All continuous predictor variables were standardized. Four steps were involved. First, we added the covariates (gender, age, duration of stay in Hong Kong, and family size) to the multiple regression equation to control for their effects. Second, maternal sacrifice was entered into the multiple regression equation. The main effect after controlling for the covariates was estimated. Then, we entered paternal sacrifice (the moderator) into the regression model. Finally, we added the interaction term of paternal and maternal sacrifice into the multiple regression equation. In case the interaction term significantly predicted the outcome variables, we further used simple slope analyses (Cohen et al. 2003) and plotted graphs to illustrate the prediction of maternal sacrifice on adolescent self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy at high (1 SD higher than the mean) and low levels (1 SD lower than the mean) of perceived paternal sacrifice respectively.

To examine the moderating effects of adolescent gender proposed in Research Question 4, we followed the statistical procedures suggested by Jaccard and Turrisi (2003). Three interaction terms, “gender X paternal sacrifice”, “gender X maternal sacrifice” and “gender X paternal sacrifice X maternal sacrifice”, were created and added to the hierarchical multiple regression model. We estimated the standardized regression coefficients of the three interaction terms.

Results

Correlational analyses showed that adolescent gender was related to paternal sacrifice and adolescent self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy. Family size and family intactness were related to paternal sacrifice, with higher levels of paternal sacrifice in intact families and families more members respectively. Other demographic characteristics (adolescents’ age and duration of stay in Hong Kong) were not related to the family and developmental attributes. Hence, gender, family intactness and family size were considered as covariates. Furthermore, paternal sacrifice was related to maternal sacrifice, adolescent self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy respectively, and maternal sacrifice was also positively related to adolescent all adolescent developmental outcomes (Table 1).

As predicted, paired t-test results showed that there was significant difference between paternal and maternal sacrifice (t = −12.66, p < .001), with maternal sacrifice having higher scores perceived by adolescents. The Cohen’s d value was 0.48, which was considered as medium according to Cohen’s suggestion (1988). Hypothesis 1 was supported.

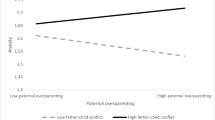

Regarding Research Questions 2 and 3, after controlling for adolescent gender and family size, it was found that both paternal and maternal sacrifice predicted adolescent self-identity, with β = .20 (p < .001) and .23 (p < .001) respectively (Table 2). Hypotheses 2a and 2b were supported. When the interaction term of perceived paternal and maternal sacrifice was added to the multiple regression equation, it was found that the interaction term of paternal and maternal sacrifice positively influenced adolescent self-identity (β = .07, p < .05; Table 2). Hypothesis 3a was supported. Maternal sacrifice positively influenced adolescent self-identity at higher levels of paternal sacrifice (β = .19, p < .001; Table 3), but the influence became non-significant at lower levels of paternal sacrifice (β = .04, p > .05; Table 3). Figure 1 plots the prediction of maternal sacrifice on adolescent self-identity as high (1 SD above the mean) and low (1SD below the mean) levels of paternal sacrifice.

Regarding adolescent self-determination, it was found that paternal sacrifice and maternal sacrifice positively predicted adolescent self-determination, with β = .16 (p < .001) and .17 (p < .001) respectively. Hypotheses 2c and 2d were supported. Moreover, the interaction term of paternal and maternal sacrifice positively predicted adolescent self-determination (β = .09, p < .05; Table 2). Hypothesis 3b was supported. When paternal sacrifice was at higher levels, maternal sacrifice positively influenced adolescent self-determination (β = .16, p < .001; Table 3). But when paternal sacrifice was at lower levels, the influence of maternal sacrifice on adolescent self-determination became non-significant (β = −.02, p > .05; Table 3). Figure 2 plots the prediction of maternal sacrifice on adolescent self-determination as high (1 SD above the mean) and low (1SD below the mean) levels of paternal sacrifice.

For adolescent self-efficacy, it was found that paternal and maternal sacrifices positively predicted adolescent self-efficacy, with β = .13 (p < .001) and .15 (p < .001) respectively. Hypotheses 2e and 2f were supported. The interaction term of paternal and maternal sacrifice marginally influenced adolescent self-efficacy (β = .07, p = .055; Table 2). Hypothesis 3c was marginally supported. When paternal sacrifice was at higher levels, maternal sacrifice positively predicted adolescent self-efficacy (β = .16, p < .001; Table 3). However, when paternal sacrifice was at lower levels, the relationship between maternal sacrifice and adolescent self-efficacy became non-significant (β = −.00, p > .05; Table 3). Figure 3 plots the prediction of maternal sacrifice on adolescent self-efficacy as high (1 SD above the mean) and low (1SD below the mean) levels of paternal sacrifice.

For Research Question 4, adolescent gender did not moderate the main effects of paternal or maternal sacrifice, and the interactive effect between paternal sacrifice and maternal sacrifice on adolescent self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy respectively (Table 2).

Discussion

This study attempted to examine the difference between adolescent perceived paternal and maternal sacrifice and investigate how perceived paternal and maternal sacrifice might interact to influence developmental outcomes (indexed by self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy) in economically disadvantaged Chinese adolescents. Consistent with the previous studies (e.g., Leung and Shek 2012), adolescents perceived maternal sacrifice to be stronger than paternal sacrifice. Furthermore, the results showed that paternal sacrifice and maternal sacrifice positively influenced adolescent self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy respectively (i.e., main effects). Paternal and maternal sacrifices serve as the protective factors for poor Chinese adolescents to build up their positive development in facing adversity and economic hardship.

As hypothesized, the interaction between paternal sacrifice and maternal sacrifice positively influenced self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy of economically disadvantaged Chinese adolescents respectively. Adolescents’ self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy were at the lowest level when both paternal and maternal sacrifice was at the lowest levels. When adolescents fail to recognize paternal and maternal sacrifice, they may perceive that their parents do not support and care about them, which hampers their positive development. On the contrary, when adolescents perceive high levels of paternal and maternal sacrifice, adolescents’ self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy are at the highest level. With the commitment and devotion of parents to their children’s development (Leung and Shek 2011a) and the family resources allocated through parental sacrifice, adolescents’ developmental outcomes are enhanced. Moreover, Chinese adolescents are more motivated to excel themselves so as to repay their parents for their sacrifice, which further enhances their personal development (Leung and Shek 2013a, 2013b).

However, adolescents exhibited only slightly higher levels of developmental outcomes when they perceived sacrifice from either parent (i.e., high levels of paternal sacrifice but low levels of maternal sacrifice, or high levels of maternal sacrifice but low levels of paternal sacrifice) than those who perceived low levels of paternal and maternal sacrifice. Even if one parent is ready to sacrifice his/her needs for nurturing their children, the family resources allocated may not be adequate for their adolescents’ positive development. Furthermore, the discrepancies may imply marital conflicts and family tensions related to resource allocation (Olson et al. 1983). This is especially important in economically disadvantaged families as the resources are tight and limited. As research on the relationships among parental sacrifice, family conflicts and adolescent development is relatively limited, the present findings provide some tentative evidence and new insights for future research.

The study has several theoretical implications. First, in the literature on family poverty, the family stress model and the family investment model (Conger and Donnellan 2007) are dominant in examining the impact of poverty on adolecent problem behaviors (e.g., drepression, anxiety, delinquent behavior) via maladaptive family practices and inadequate family investment. However, the impact of family contributions on adolescent development is under-researched (Shek 2010). Particularly, fewer studies focused on family quality of life that is culturally specific. In fact, culture plays a critical role in shaping parental behavior and adolescent development (Bornstein and Cheah 2006). This study identifies paternal sacrifice and maternal sacrifice as well as their interaction as the protective factors in influencing adolescent developmental outcomes in economically disadvantaged Chinese families. The findings provide important insights by identifying the positive family attributes in the Chinese contexts, which facilitate the development of the Chinese model of family resilience. Second, the results suggested that paternal sacrifice interacted with maternal sacrifice to affect adolescent developmental outcomes, which highlights the importance of joint efforts of fathers and mothers in nurturing their children. As pointed out by Walsh (2016) that mutual partnership between the father and mother is essential for the families to face adversity and overcome daily challenges, this study provides evidence on the importance of mutual parental contributions to enhance adolescent positive development in economically disadvantaged Chinese families.

The findings of the present study also show important implications for practice. First, the results showed that adolescents perceived more maternal sacrifice than paternal sacrifice. As most economically disadvantaged fathers are engaged in physically demanding jobs with long hours of work and they are less expressive to talk about their sacrifice to their family members (Leung and Shek 2012), paternal sacrifice becomes less “visible” for the adolescents. Hence, it is necessary to enhance more mutual communications between fathers and adolescents so that adolescents can recognize their fathers’ sacrifice for their development. Second, the findings indicated that adolescents’ self-identity, self-determination and self-efficacy are at the highest levels when they perceived both parents sacrifice for their development, when compared to those perceiving either one or none parents would sacrifice for them. However, due to the limited resources in poor families, interparental conflicts and withdrawal may arise on allocation of resources (Conger et al. 2010; Leung 2018). Hence, family practitioners may need to pay more attention to these families that suffer from family tensions and interparental conflicts. Family practitioners may need to adopt a family-based intervention approach to understand the dynamics of the families and assist the families to manage the family tensions.

Despite the pioneering nature of the study, there are several limitations of the study. First, the present study is a cross-sectional study that may have problems of inferring cause-and-effect relationships among the variables. A longitudinal study is recommended for future studies. Second, the study adopted the adolescents’ perception to measure parental sacrifice without taking the parents’ perspectives into account. Though adolescents are the “receivers” of the family practice (Elstad and Stefansen 2014) and their subjective family experience is critical in predicting their development, the parents may have different perceptions of family processes (Leung and Shek 2016). To gain a more comprehensive picture, it is methodologically preferred to gather different views from multiple informants (i.e., parents and adolescents). Third, the study collected the data from a sample of Chinese adolescents experiencing economic disadvantage in Hong Kong. It is advised to replicate the study in different Chinese communities (e.g., mainland China, American-Chinese communities) to generalize the findings in different contexts.

Despite of the limitations, the present study is pioneering in understanding the main and interaction effects of paternal and maternal sacrifice on adolescent developmental outcomes in Chinese families experiencing economic disadvantage. Essentially, the findings provide important cues for social science researchers and theorists on the understanding of family dynamics and their impacts on adolescent developmental outcomes in the Chinese families experiencing economic disadvantage, which may help to formulate the social policies to alleviate intergenerational poverty.

References

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman.

Barajas, R. G., Philipsen, N., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2008). Cognitive and emotional outcomes of children in poverty. In D. R. Crane & T. B. Heaton (Eds.), Handbook of families and poverty (pp. 311–333). Los Angeles: Sage.

Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42, 155–162.

Berzonsky, M. D. (1994). Self-identity: The relationship between process and content. Journal of Research in Personality, 28(4), 453–460.

Bornstein, M. H., & Cheah, C. S. L. (2006). The place of “culture and parenting” in the ecological contextual perspective on developmental science. In K. H. Rubin & O. B. Chung (Eds.), Parenting beliefs, behaviors, and parent-child relationship (pp. 3–34). New York: Taylor & Francis.

Bradley, R. H., & Corwyn, R. F. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 371–399.

Catalano, R. F., Berglund, M. L., Ryan, J. A. M., Lonczak, H. S., & Hawkins, J. D. (2002). Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. Prevention & Treatment, 5(1), 1–111.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Collins, A., & Russell, S. (1991). Mother-child and father-child relations in adolescence: A developmental analysis. Developmental Review, 11, 99–136.

Conger, R. D., & Donnellan, M. B. (2007). An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 175–199.

Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., & Martin, M. J. (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 685–704.

Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (1997). Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology, 45, 243–267.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

Elstad, J. I., & Stefansen, K. (2014). Social variations in perceived parenting styles among Norwegian adolescents. Child Indicators Research, 7, 649–670.

Forehand, R., & Nousiainen, S. (1993). Maternal and paternal parenting: Critical dimensions of adolescent functioning. Journal of Family Psychology, 7(2), 213–221.

Jaccard, J., & Turrisi, R. (2003). Interaction effects in multiple regression (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Laible, D. J., & Carlo, G. (2004). The differential relations of maternal and paternal support and control to adolescent social competence, self-worth, and sympathy. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19(6), 759–782.

Lam, C. M. (2005). In search of the meaning of parent education in the Hong Kong-Chinese context. In M. J. Kane (Ed.), Contemporary issues in parenting (pp. 111–124). New York: Nova Science.

Leung, J. T. Y. (2018). Parent-adolescent discrepancies in perceived parental sacrifice and adolescent developmental outcomes in poor Chinese families. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 28(2), 520–536.

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2011a). “All I can do for my child” - development of the Chinese parental sacrifice for Child’s education scale. International Journal of Disability and Human Development, 10(3), 201–208.

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2011b). Validation of the Chinese parental sacrifice for Child’s education scale. International Journal of Disability and Human Development, 10(3), 209–215.

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2012). Parental differences in family processes in Chinese families experiencing economic disadvantage. Géneros. Multidisciplinary Journal of Gender Studies, 1(3), 242–273.

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2013a). Are family processes related to achievement motivation of Chinese adolescents experiencing economic disadvantage in Hong Kong? International Journal of Disability and Human Development, 12(2), 115–125.

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2013b). Parenting for resilience: Family processes and psychosocial competence of Chinese adolescents experiencing economic disadvantage in Hong Kong. Journal of Disability and Human Development, 12(2), 127–137.

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2015). Parental beliefs and parental sacrifice of Chinese parents experiencing economic disadvantage in Hong Kong: Implications for social work. British Journal of Social Work, 45(4), 1119–1136.

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2016). Parent-child discrepancies in perceived parental sacrifice and achievement motivation of Chinese adolescents experiencing economic disadvantage. Child Indicators Research, 9, 683–700.

Leung, J. T. Y., Shek, D. T. L., & Ma, C. M. S. (2015). Measuring perceived parental sacrifice among adolescents in Hong Kong: Confirmatory factor analyses of the Chinese parental sacrifice scale. Child Indicators Research, 9, 173–192.

Linver, M. R., & Silverberg, S. B. (1997). Maternal predictors of early adolescent achievement-related outcomes: Adolescent gender as moderator. Journal of Early Adolescence, 17(3), 294–318.

Luszczynska, A., Gutiérrez-Doña, B., & Schwarzer, R. (2005). General self-efficacy in various domains of human functioning: Evidence from five countries. International Journal of Psychology, 40, 80–89.

Meeus, W. (1996). Studies on identity development in adolescence: An overview of research and some new data. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 25(5), 569–598.

Minuchin, P. (1985). Families and individual development: Provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Development, 56, 289–302.

Olson, D. H., McCubbin, H. I., Larsen, A. S., Muxen, M. J., & Wilson, M. A. (1983). Families: What makes them work. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Plunkett, S. W., Henry, C. S., Robinson, L. C., Behnke, A., & Falcon III, P. C. (2007). Adolescent perceptions of parental behaviors, adolescent self-esteem, and adolescent depressed mood. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16(6), 760–772.

Rubin, A., & Babbie, E. R. (2017). Research methods for social work. Boston: Cengage Learning.

Rueger, S., Malecki, C., & Demaray, M. (2010). Relationship between multiple sources of perceived social support and psychological and academic adjustment in early adolescence: Comparisons across gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(1), 47–61.

Shek, D. T. L. (2005). A longitudinal study of perceived family functioning and adolescent adjustment in Chinese adolescents with economic disadvantage. Journal of Family Issues, 26(4), 518–543.

Shek, D. T. L. (2004). Chinese cultural beliefs about adversity: Its relationship to psychological well-being, school adjustment and problem behavior in Chinese adolescents with and without economic disadvantage. Childhood, 11, 63–80.

Shek, D. T. L. (2010). Quality of life of Chinese people in a changing world. Social Indicators Research, 95, 357–361.

Shek, D. T. L., Siu, A. M. H., & Lee, T. Y. (2007). The Chinese positive youth development scale: A validation study. Research on Social Work Practice, 17, 380–391.

Tsang, S. K. M., Hui, E. K. P., & Law, B. C. M. (2012). Positive identity as a positive youth development construct: A conceptual review. The Scientific World Journal, 2012, Article ID 529691. https://doi.org/10.1100/2012/529691.

Walsh, F. (2016). Strengthening family resilience. New York: Guilford.

Wang, M., & Eccles, J. (2012). Social support matters: Longitudinal effects of social support on three dimensions of school engagement from middle to high school. Child Development, 83(3), 877–895.

Wyman, P. A. (2003). Emerging perspectives on context specificity of children’s adaptation and resilience. In S. S. Luthar (Ed.), Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversities (pp. 293–317). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yeh, M. H., & Yang, K. S. (1997). Chinese familism: Conceptual analysis and empirical assessment. Bulletin of the Institute of Ethnology. Academia Sinica (Taiwan), 83, 169–225.

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the Early Career Scheme, Research Grants Council (Project Code: PolyU 216008/15H).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The first author is the Associate Editor of ARQOL. The second author is the Editor in Chief of ARQOL. Hence an editorial board member has been invited to be the Action Editor.

Ethical Standard

The author declares that all procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of Human Subjects Ethics Sub-committee of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants and their parents.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leung, J.T.Y., Shek, D.T.L. Relationships between Perceived Paternal and Maternal Sacrifice and Developmental Outcomes of Chinese Adolescents Experiencing Economic Disadvantage. Applied Research Quality Life 16, 2371–2386 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-020-09821-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-020-09821-6