Abstract

This study examines the relationships amongst perceived paternal and maternal sacrifice, filial piety and adolescent life satisfaction in a sample of 716 poor adolescents studying in Grade 7 and Grade 8 in Hong Kong. Based on the family capital theory and the Chinese socialization model, it was hypothesized that reciprocal filial piety and authoritarian filial piety would mediate the relationship between parental sacrifice and adolescent life satisfaction. Results based on structural equation modeling indicated that while both reciprocal and authoritarian filial piety partially mediated the relationship between paternal sacrifice and adolescent life satisfaction, the influence of maternal sacrifice on adolescent life satisfaction was fully mediated by reciprocal and authoritarian filial piety. The significant relationships were found to be stable in adolescent boys and girls. The research findings underscore the role of parental sacrifice in cultivating filial piety and life satisfaction in Chinese adolescents experiencing economic disadvantage, which provides insights for the development of Chinese family models in the context of poverty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is ample evidence showing that poverty impairs the development and wellbeing of adolescents and their families. The family stress model suggests that economic stresses have negative impacts on adolescent wellbeing via disruptive parenting and family conflicts (Conger et al. 2010; Grant et al. 2003; Mistry et al. 2008). On the other hand, the family investment model proposes that poor families may not have adequate resources for healthy adolescent development (Conger et al. 2010). Hence, adolescents growing up in economic hardship generally have poorer quality of life (Dashiff et al. 2009; Yoshikawa et al. 2012).

While some family processes (e.g., disruptive parenting, family conflicts) are risk factors that contribute to poorer adolescent wellbeing (Conger et al. 2010; Yoshikawa et al. 2012), other family processes (e.g., family cohesion, parental support) serve as protective factors that promote adolescent psychosocial wellbeing in the context of poverty (Benzies and Mychasiuk 2009; Walsh 2016). Jessor and Jessor (1977) suggested that adolescent behavior was the consequence of the interplay between risk factors and protective factors within the family system. Hence, it is important to examine the family processes that contribute to adolescent wellbeing and development in the context of poverty. Against this background, this study examined parental (paternal and maternal) sacrifice as protective factors of Chinese adolescents experiencing economic disadvantage in Hong Kong, assessed the mediation effects of filial piety (authoritarian and reciprocal) on the relationship between parental (paternal and maternal) sacrifice and adolescent life satisfaction, and investigated whether there would be a difference between adolescent boys and girls in the proposed model. The findings may shed new lights on the development of Chinese family model in the context of poverty, which contribute to the social science literature on resilience.

Research Gaps on Family Studies in the Context of Poverty

There are several research gaps pertinent to research on family processes that influence adolescent quality of life in the context of poverty. First, majority of studies examined parenting practice and family functioning without paying much attention to the role of culture in determining the features of child socialization (Bornstein and Cheah 2006). In fact, Chinese socialization is different from Western socialization as the former focuses on collectivism, familism and interdependence, whereas the latter points to the value of individualism, autonomy and independence (Shek 2006). Hence, there is a need to consider family attributes (e.g., socialization strategies, family life, parent-child relational qualities) that are culturally specific in the Chinese contexts (Shek and Lee 2007). Second, many related studies attempted to identify protective factors for families against economic hardship, but few studies investigated the mechanisms on how these protective factors work. Third, majority of studies considered “parents” as an entity (Kiernan and Mensah 2011; Russell et al. 2008) without differentiating the specific roles of fathers and mothers in the family separately. In fact, based on the social role theory (Eagly and Wood 1999), fathers are expected to be the breadwinners of the families, whereas mothers are responsible for childrearing and housework management. As the contributions of fathers and mothers may vary, it is necessary to examine paternal and maternal contributions to adolescent wellbeing and development separately. Fourth, many related studies explored adolescent development and wellbeing in terms of internalizing (e.g., depression, suicide) and externalizing (e.g., hostility, delinquent behaviors) behavioral outcomes (Conger et al. 1994; Solantaus et al. 2004), with few studies examining the quality of life of adolescents experiencing economic disadvantage. As a positive indicator of one’s wellbeing, life satisfaction is an important psychological strength leading to one’s adaptive development (Antaramian et al. 2008). This attribute is particularly important for economically disadvantaged adolescents in solving the developmental and ecological challenges (Shek 2008). To fill in the research gaps, this study attempted to examine how filial piety (authoritarian and reciprocal) would mediate the influence of parental (paternal and maternal) sacrifice on adolescent life satisfaction in Chinese poor families. Both parental sacrifice and filial piety are regarded as unique features in Chinese socialization attributes (Lam 2005; Yeh and Bedford 2003).

Parental Sacrifice and Adolescent Life Satisfaction

Among the family processes, parental sacrifice is a central feature of Chinese parenthood, where parents are obligated to subordinate their interests and desires for the welfare of their children (Lam 2005). Parental sacrifice is defined as “a process by which parents give up their personal needs for the sake of educational and developmental needs of their children” (Leung and Shek 2015, p. 1123). It involves three processes. First, adolescents’ education and development demand the use of family resources in terms of money, time and parents’ effort. Second, parents need to juggle with different demands because the family resources are sparse. Third, parents decide to use the family resources for the educational and developmental needs of their children at the expense of their personal needs and desires (Leung and Shek 2011a). Leung and Shek (2011a) identified five dimensions of parental sacrifice, including mobilization of financial resources, time spent on children’s education, reorganization of everyday routine, personal sacrifice and shielding of worries.

Based on the social capital theory of a family (Coleman 1990), family social capital (e.g., parenting, parent-child relational quality) links up financial capital (i.e., family resources) and human capital (i.e., parents’ education) of the family to promote psychosocial development of the offspring. Generally speaking, there are three mechanisms through which parental sacrifice promotes adolescent wellbeing. First, parental sacrifice represents parental love and devotion in the socialization process, which promotes adolescent wellbeing in providing a supportive environment (Leung and Shek 2013a, 2013b). Second, the family resources allocated to their children promote their cognitive and psychosocial development (Conger et al. 2010). This is especially crucial for poor families as their family resources are sparse. Third, parental sacrifice promotes mutual trust and positive relationship between parents and children, which enhances adolescent psychosocial wellbeing (Laible and Carlo 2004).

Filial Piety as a Mediator

Central to the doctrine of familism, filial piety is the guiding virtue for regulating intergenerational behavior in the Confucian ethics (Ho 1996). However, rather than considering filial piety as a unidimensional construct, Yeh and Bedford (2003) conceptualized it into two categories: authoritarian filial piety and reciprocal filial piety. While authoritarian filial piety demands the suppression of one’s desire in compliance with parental wishes and brings glory to one’s parents through maintaining family’s reputation, reciprocal filial piety entails care and support to one’s parents, as well as emotional and practical attention to one’s parents as gratitude for their nurturance (Yeh and Bedford 2003). The former is guided by obedience toward normative authority of a hierarchical family system, whereas the latter is generated from intimacy and mutual relatedness within the family dyad (Yeh et al. 2013).

In the Chinese culture, the parent-child interdependent relationship is a unique feature in the Chinese socialization (Chao and Tseng 2002). According to the Confucian ideologies, parents are expected to devote their love and attention to their children out of benevolence, and reciprocally children should respect and follow the rules of their parents out of filial piety (Yeh and Yang 1997). Adolescents who experience parental sacrifice would develop a sense of gratitude to repay their parents’ love and devotion for their development (i.e., reciprocal filial piety). At the same time, adolescents who make sense of the strong wishes behind parental sacrifice (i.e., to excel and gain family pride) may behave according to their parents’ expectations (i.e., authoritarian filial piety; Bempechat et al. 1999; Fuligni and Yoshikawa 2003). Hence, it is expected that adolescents develop filial piety when they perceive parental sacrifice for their education and development, and are more motivated to strive for excellence and achievement to repay their parents for their sacrifice. In a study of low-income immigrant families in the United States, Fuligni and Yoshikawa (2003) showed that in response to sacrifice of the parents, a sense of filial obligation motivated adolescents toward academic achievement and turned them away from problem behavior. Leung and Shek (2016a) further showed that filial piety mediated the relationship between positive family functioning and adolescent psychosocial competence in poor single-mother families. However, previous studies regarded filial piety as a unidimensional attribute without taking the dimensions of authoritarian and reciprocal filial piety into account. In this study, we posited that reciprocal filial piety mediated the relationship between parental sacrifice and adolescent life satisfaction because of children’s gratitude for their parents’ nurturance. Similarly, it was hypothesized that authoritarian filial piety would mediate the relationship between parental sacrifice and adolescent life satisfaction due to the familial obligation in fulfilling parental wishes underling the sacrifice.

Parent Gender and Adolescent Gender

As the breadwinners of the families, fathers are the authority figures in the family hierarchy (Chao and Tseng 2002). Their decisions and behavior are more influential to adolescents. In the previous study, it was found that paternal sacrifice had stronger influence on adolescent development in poor Chinese families than did maternal sacrifice (Leung and Shek 2013a). However, the mediation effects of filial piety on the relationships between paternal and maternal sacrifice and adolescent wellbeing have not been examined in the literature.

Regarding the role of adolescent gender, the findings are not conclusive in the previous studies. While adolescent girls were more receptive to the influence of parental affection than were boys (Linver and Silverberg 1997; Plunkett et al. 2007), other studies did not find any difference between boys and girls on the prediction of parental support on adolescent development (Rueger et al. 2010; Wang and Eccles 2012). As opposed to the Chinese traditional practice that “sons are cherished and daughters are slighted” (Stacey 1983; Su and Hynie 2011), recent research showed that Chinese parents have become more egalitarian in parenting and providing resources for their children’s education and development, regardless of their children’s gender (Chan et al. 2009; Lu and Chang 2013). Hence, it was hypothesized that there is invariance between adolescent boys and girls in the mediation effects of filial piety on the relationship between parental sacrifice and life satisfaction of poor Chinese adolescents.

The Current Study

This study attempted to examine the mediation effects of filial piety on the relationship between parental sacrifice and adolescent life satisfaction of poor Chinese families in Hong Kong. There were two research questions in the study:

Research Question 1: Do authoritarian filial piety and reciprocal filial piety mediate the relationship between parental (paternal and maternal) sacrifice and adolescent life satisfaction in poor Chinese families? Based on the social capital theory (Coleman 1990) and the Chinese socialization model (Yeh and Yang 1997), adolescents develop a sense of reciprocal filial piety that motivates them to excel so as to express their gratitude for their parents’ nurturance, and cultivate a sense of authoritarian filial piety to fulfill parental wishes underling the sacrifice. By fulfilling the roles of a “good child”, adolescents gain a sense of life satisfaction. Hence, it was hypothesized that authoritarian filial piety and reciprocal filial piety would mediate the relationship between parental (paternal and maternal) sacrifice and adolescent life satisfaction in poor Chinese families.

Research Question 2: Is there any difference between adolescent boys and girls in the mediation effects of filial piety (authoritarian and reciprocal) in the influence of paternal and maternal sacrifice on adolescent life satisfaction in poor Chinese families? Based on previous studies that there was invariance between boys and girls on the prediction of parental support on adolescent development (Rueger et al. 2010; Wang and Eccles 2012), it was hypothesized that the mediation effects of filial piety (authoritarian and reciprocal) in the relationship between paternal and maternal sacrifice and adolescent life satisfaction in poor Chinese families would be consistent in adolescent boys and girls.

Method

Participants

As a complete list of poor families was lacking in Hong Kong, we adopted a stratified cluster sampling method (Rubin and Babbie 2017) of secondary schools to recruit the respondents, with school banding as the stratifying factor. There were 12 secondary schools participating in the study, with 729 economically disadvantaged students in Secondary 1 and 2 (Grade 7 and 8) participated as the respondents. The respondents were recipients of the Government-supported means-tested cash assistance programs for the families under the poverty threshold, including the Comprehensive Social Security Assistance (CSSA), the Full Textbook Allowance (TBA), and the Low-income Working Family Allowance Scheme (LIFA). Thirteen questionnaires were found invalid due to the incomplete information. Finally, 716 questionnaires were analysed.

There were 365 boys (51.0%) and 349 girls (48.7%) in the sample. The mean age of the adolescents was 13.22 (SD = 0.99), with 417 adolescents (58.2%) studying in Secondary 1 (Grade 7) and 298 (41.6%) studying in Secondary 2 (Grade 8). The uneven distribution between the two grades was due to the fact that one secondary school only invited Secondary 1 students to join the study. While 502 students (70.1%) were born in Hong Kong, 209 students (29.2%) were immigrants from mainland China. The gender ratio was comparable with the Hong Kong population statistics at 2016 (the male-to-female ratio at the category of age between 10 and 14 category was 1.07 to 1, and 74.2% were born in Hong Kong; Census and Statistical Department 2017).

Procedures

The data collection was performed by the first author and the trained research assistants. The respondents were given information about the research purposes, data collection procedures, the right to voluntarily participate in and withdraw from the study, and the use of the data. Written informed consent was obtained from the respondents and their parents. The respondents were invited to fill out a questionnaire that contained measures of perceived paternal and maternal sacrifice, filial piety, life satisfaction and some questions on demographic background (e.g., gender, age, immigrant status, family size). They were given adequate time to complete the questionnaires. Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Subjects Ethics Sub-committee of an internationally recognized university.

Measurements

Parental Sacrifice

Chinese Paternal/Maternal Sacrifice Scale (PSA/MSA)

Based on the literature related to family capital (Coleman 1990) and family investment (Conger et al. 2010), as well as the qualitative findings of Chinese parents and adolescents, indigenous measurements of PSA and MSA that measure paternal and maternal sacrifice were developed respectively (Leung and Shek 2011a). The scale showed good reliability, convergent validity and factorial validity in previous studies (Leung and Shek 2011b; Leung et al. 2016). In this study, perceived paternal and maternal sacrifice from the perspectives of adolescents were measured. All items were rated on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 6 = “strongly agree”. A sample item is “Even if my father/mother feels tired, he/she tries his/her best to understand my school life”. Higher mean scores of PSA and MSA indicate higher levels of paternal and maternal sacrifice respectively. Both PSA and MSA showed good reliability in the study (PSA: Cronbach’s alpha = .96; MSA: Cronbach’s alpha = .95).

Filial Piety

Filial Piety Scale (FPS)

Based on the conceptualization of filial piety developed by Yeh and Bedford (2003), a 12-item Filial Piety Scale (FPS) was used to measure authoritarian filial piety (AFP; 6 items) and reciprocal filial piety (RFP; 6 items) respectively. A sample item of AFP is “Listen to parents’ advice on decision about future career” and that of RFP is “Be grateful to your parents for raising you”. All items were rated on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 6 = “strongly agree”, with higher mean scores of AFP and RFP indicating higher levels of authoritarian and reciprocal filial piety, respectively. Both AFP and RFP showed good reliability in the study (AFP: Cronbach’s alpha = .80; RFP: Cronbach’s alpha = .91).

Life Satisfaction

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

Shek (1992) translated the SWLS to assess one’s global judgment on one’s quality of life based on the work of Diener and his colleagues (Diener et al. 1985). A sample item is “In most ways my life is close to my ideal”. All items were rated on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 6 = “strongly agree”. Higher mean scores of SWLS indicate higher levels of life satisfaction. SWLS showed good reliability in the study (Cronbach’s alpha = .87).

Data Analyses

Missing data is not a problem in the present study. We performed structural equation modeling (SEM) using AMOS 23.0 software to address Research Question 1 (i.e., mediation effects of filial piety on the relationship between parental sacrifice and life satisfaction of poor Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong). We used three goodness-of-fit indices to test the model fit: (i) chi-square (x2) having a non-significant probability score to indicate a closer fit of the hypothetical model; (ii) the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) having a value greater than 0.90 to represent a good fit of the tested model; and (iii) the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) value lower than 0.06 to indicate a good fit, and between 0.06 and 0.08 to indicate an acceptable fit of the tested model (Hu and Bentler 1999). We followed the procedures suggested by Baron and Kenny (1986) to analyze the mediation effects. First, direct influences of paternal and maternal sacrifice on adolescent life satisfaction were estimated. Then, authoritarian filial piety and reciprocal filial piety were added to the tested model as mediators. Both direct and indirect effects were estimated. At the same time, a bootstrapping mediation test (Preacher and Hayes 2008) with 5000 bootstrapped re-samples was used to assess the significance of mediation effects. In case a “zero” value was not found between the upper and lower bounds of bias corrected 95% confidence intervals, the mediation effect was supported (Preacher and Hayes 2008).

Regarding Research Question 2, multiple group analysis was performed to assess whether there would be a difference between adolescent boys and girls in the tested model. The chi-square difference test and CFI difference (i.e., ΔCFI > .01; Cheung and Rensvold 2002) were used to assess the differences between two groups in the tested model.

Results

Correlational analyses adopting a two-tailed multistage Bonferroni procedure (Larzelere and Mulaik 1977) indicated that adolescent gender was associated with life satisfaction, with boys showing higher levels of life satisfaction. Besides, family size was positively associated with paternal sacrifice. Furthermore, it was found that paternal sacrifice and maternal sacrifice were positively related to authoritarian and reciprocal filial piety, and life satisfaction (Table 1). Adolescent gender and family size were controlled for in testing the mediation model of filial piety on the relationship between parental sacrifice and adolescent life satisfaction.

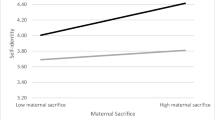

Regarding Research Question 1, the direct effect of paternal and maternal sacrifice on life satisfaction showed a model fit of the data, with x2(5) = 10.64, p > .05, CFI = .98 and RMSEA = .04. It was found that both paternal sacrifice and maternal sacrifice positively influenced adolescent life satisfaction, with b = .23, SE = .04 (p < .001) and b = .10, SE = .04 (p < .05). When authoritarian and reciprocal filial piety were put into the model as mediators, the mediation model also showed a good fit of the data, with x2(9) = 12.47, p > .05, CFI = .996 and RMSEA = .02. The tested model accounted for 23% of the total variance of adolescent life satisfaction. The findings indicated that filial piety (both reciprocal and authoritarian) partially mediated the relationship between paternal sacrifice and adolescent life satisfaction, with significant direct effect of paternal sacrifice on adolescent life satisfaction (b = .18, SE = .05, p < .001), indirect effects via reciprocal filial piety (b = .05, SE = .01, p < .001) and via authoritarian filial piety (b = .06, SE = .02, p < .001).

Regarding maternal influence, reciprocal filial piety and authoritarian filial piety fully mediated the influence of maternal sacrifice and adolescent life satisfaction, with b = .05, SE = .02 (p < .001) and b = .05, SE = .02 (p < .001), respectively. The direct effect of maternal sacrifice on adolescent life satisfaction became non-insignificant (b = .08, SE = .05, p > .05) when both indices of filial piety were included in the model. Figure 1 shows the mediation model in which filial piety (reciprocal and authoritarian) mediated the relationships between parental (paternal and maternal) sacrifice and life satisfaction of Chinese adolescents experiencing economic disadvantage in Hong Kong. Table 2 shows the direct, indirect and total effects of the influences.

Regarding Research Question 2, multiple group analysis was performed to compare the constrained model (i.e., all predictor paths were set equal between male and female groups) with the unconstrained model. Results showed that the unconstrained model showed a good data fit, with x2(10) = 19.87, p < .05, CFI = .989 (> .90) and RMSEA = .04 (< .06; Hu and Bentler 1999). When all predictor paths were assumed to be equal between male and female groups (i.e., the constrained model), the model fitted the data well (x2(17) = 32.77, p < .05, CFI = .983 and RMSEA = .04). The chi-square difference test showed that the difference between male and female groups on the tested model was non-significant (Δx2 = 12.90, p > .05), and the change of CFI was .006 (< .01), suggesting that there was invariance of main and mediation effects between adolescent boys and girls.

Discussion

This study attempted to examine the mediation effects of filial piety (authoritarian and reciprocal) on the relationship between parental (paternal and maternal) sacrifice and adolescent life satisfaction of Chinese families experiencing economic disadvantage in Hong Kong. The findings suggest that both authoritarian filial piety and reciprocal filial piety partially mediate the relationship between paternal sacrifice and adolescent life satisfaction, and they fully mediate the influence of maternal sacrifice and adolescent life satisfaction. Moreover, the direct and indirect effects were found stable across adolescent gender. The study echoes the social capital theory (Coleman 1990) that paternal sacrifice and maternal sacrifice serve as protective factors influencing adolescent life satisfaction in poor Chinese families. Furthermore, the results provide some support for the Chinese socialization model (Yeh and Yang 1997) that filial piety mediates the relationships between parental (paternal and maternal) sacrifice and adolescent life satisfaction.

There are four notable observations from the findings. First, relative to maternal sacrifice, paternal sacrifice was a stronger predictor on adolescent life satisfaction. In the Chinese culture in which patriarchal hierarchy is emphasized (Chao and Tseng 2002), fathers are regarded as authority figures and decision makers of the families. Their decisions and behaviors are more influential to adolescent wellbeing and development. Besides, as fathers are the main breadwinners of the families, they pay extraordinary effort to strive for financial resources for their families in the context of poverty (Leung and Shek 2013b). Hence, when adolescents perceive paternal sacrifice, support and devotion for their development, they exhibit higher levels of life satisfaction even living in poverty. The results echo with previous studies showing that paternal sacrifice rather than maternal sacrifice predicts adolescent achievement motivation and psychological competence in poor Chinese families (Leung and Shek 2013a, b).

The second observation is that paternal sacrifice predicted adolescent life satisfaction directly and indirectly via filial piety, whereas filial piety fully mediated the relationship between maternal sacrifice and life satisfaction perceived by adolescents. As mentioned, paternal sacrifice represents the love and commitment of their fathers toward the families (Leung and Shek 2016c), and previous studies show that paternal behavior is more influential to adolescent development (Lamb and Lewis 2010; Leung and Shek 2013a, b). Hence, it is plausible that paternal sacrifice directly influences adolescent life satisfaction, apart from the indirect effect via filial piety.

Third, it is understandable that parental sacrifice entails the love and commitment of parents toward their children’s nurturance, which promotes reciprocal filial piety to repay their parents for their sacrifice. However, the results indicated that authoritarian filial piety also mediated the relationship between parental sacrifice and adolescent life satisfaction. Parental sacrifice is a manifestation of parental expectations of their children to have a better future development (Leung and Shek 2015). This is especially important for poor families. Underlying their sacrifice, parental expectations on adolescents to escape from intergenerational poverty are salient. Embedded in the Chinese culture, children are expected to bring glory to their parents by striving for excellence (Yeh and Yang 1997). They develop their life goals according to their parents’ expectations. Hence, it is plausible that authoritarian filial piety mediates the relationship between parental sacrifice and adolescent life satisfaction.

Fourth, adolescent gender did not moderate the direct and indirect effects of parental (paternal and maternal) sacrifice, filial piety and adolescent life satisfaction, suggesting that the impact of the family processes under study are relatively stable in adolescent boys and girls.

There are several theoretical and practical implications of the present findings. First, the study provides important insights on the direct effect and mediating mechanisms on how parents contribute to adolescent life satisfaction in poor Chinese families. The findings contribute to the development of Chinese family model in the context of poverty. Second, the results indicated that relative to maternal sacrifice, paternal sacrifice was more influential to adolescent life satisfaction in poor Chinese families. The study fills in the gap on examining the effects of paternal contribution on adolescent wellbeing. Third, rather than considering filial piety as a unidimensional construct that describes the intergenerational relationship embedded in the Chinese culture, the study regarded filial piety as a multi-dimensional construct having both authoritarian and reciprocal dimensions. The findings indicated that both authoritarian and reciprocal filial piety mediated the relationship between parental sacrifice and adolescent life satisfaction, which enriches our understanding of the family dynamics within the Chinese families.

Practically, the study provides important cues for social service practitioners in developing effective intervention strategies to help the families living in poverty. The results showed that parental sacrifice influenced adolescent wellbeing via filial piety, which underscores the importance of family-based intervention in helping poor Chinese families. Moreover, acknowledgement of parental sacrifice is crucial for adolescents to cultivate filial obligations toward their families, which further motivates them to behave well and develop positively. Social service practitioners may need to enhance mutual communication between parents and adolescents, and let adolescents build a sense of gratitude for their parents’ sacrifice.

Furthermore, although paternal sacrifice was found influential to adolescent wellbeing in poor Chinese families, it is noteworthy that economically disadvantaged fathers mostly engage in long hours of work which limit their time for father-adolescent interactions (Leung and Shek 2016b). Also, fathers are less expressive to share their sacrifice to the adolescents (Leung 2017). Hence, social service practitioners may need to encourage fathers to share with their children, and let adolescents understand their fathers’ contributions through their interactions.

There are several limitations of the study. First, as the cross-sectional design of the study has the limitation to infer causal effects of the relationships among parental sacrifice, filial piety and adolescent life satisfaction, a longitudinal study is recommended in future studies. Second, the data were based on the perceptions of parental sacrifice from adolescent’s perspectives. Though it is justified that adolescents serve as the recipients of family contributions (Elstad and Stefansen 2014) and their subjective perceptions are more crucial in predicting their wellbeing (Leung and Shek 2016b), parents may have different views of parental sacrifice and their perceptions may provide another perspective in understanding the relationships (Leung 2017). Hence, it is methodologically preferred to collect data from both parents and adolescents. Third, as the data were collected from Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong, there is a need to replicate the study in other Chinese populations such as the mainland Chinese and American Chinese.

Despite the limitations, the study brings important insights promoting our understanding of how parental sacrifice influences adolescent quality of life in poor Chinese families. More importantly, the findings provide insights for scholars and social service practitioners to formulate effective intervention strategies in helping the families experiencing economic disadvantage so that their wellbeing could be enhanced eventually.

References

Antaramian, S. P., Huebner, E. S., & Valois, R. F. (2008). Adolescent life satisfaction. Applied Psychology, 57(s1), 112–126.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Bempechat, J., Graham, S. E., & Jimenez, N. V. (1999). The socialization of achievement in poor and minority students: a comparative study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30(2), 139–158.

Benzies, K., & Mychasiuk, R. (2009). Fostering family resiliency: a review of the key protective factors. Child & Family Social Work, 14(1), 103–114.

Bornstein, M. H., & Cheah, C. S. L. (2006). The place of “culture and parenting” in the ecological contextual perspective on developmental science. In K. H. Rubin & O. B. Chung (Eds.), Parenting beliefs, behaviors, and parent-child relationship (pp. 3–34). New York: Taylor & Francis.

Census and Statistical Department. (2017). 2016 Population By-census: Main Results [Electronic version]. Retrieved September 7, 2018 from https://www.bycensus2016.gov.hk/data/16bc-main-results.pdf.

Chan, S. M., Bowes, J., & Wyver, S. (2009). Chinese parenting in Hong Kong: links among goals, beliefs and styles. Early Child Development and Care, 179(7), 849–862.

Chao, R. K., & Tseng, V. (2002). Parenting in Asians. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: social conditions and applied parenting (Vol. 4, pp. 59–93). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 233–255.

Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Conger, R. D., Ge, X., Elder Jr., G. H., Lorenz, F. O., & Simons, R. L. (1994). Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development, 65, 541–561.

Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., & Martin, M. J. (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 685–704.

Dashiff, C., DiMicco, W., Myers, B., & Sheppard, K. (2009). Poverty and adolescent mental health. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 22(1), 23–32.

Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (1999). The origins of sex differences in human behavior: evolved dispositions versus social roles. American Psychologist, 54, 408–423.

Elstad, J. I., & Stefansen, K. (2014). Social variations in perceived parenting styles among Norwegian adolescents. Child Indicators Research, 7, 649–670.

Fuligni, A. J., & Yoshikawa, H. (2003). Socioeconomic resources, parenting, poverty, and child development among immigrant families. In M. H. Bornstein & R. H. Bradley (Eds.), Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child development (pp. 107–124). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Grant, K. E., Compas, B. E., Stuhlmacher, A. F., Thurm, A. E., McMahon, S. D., & Halpert, J. A. (2003). Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: moving from markers to mechanisms of risk. Psychological Bulletin, 129(3), 447–466.

Ho, D. Y. F. (1996). Filial piety and its psychological consequences. In M. H. Bond (Ed.), The handbook of Chinese psychology (pp. 155–165). Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Jessor, R., & Jessor, S. L. (1977). Problem behavior and psychosocial development: a longitudinal study of youth. San Diego: Academic Press.

Kiernan, K. E., & Mensah, F. K. (2011). Poverty, family resources and children’s early educational attainment: the mediating role of parenting. British Educational Research Journal, 37(2), 317–336.

Laible, D. J., & Carlo, G. (2004). The differential relations of maternal and paternal support and control to adolescent social competence, self-worth, and sympathy. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19(6), 759–782.

Lam, C. M. (2005). In search of the meaning of parent education in the Hong Kong-Chinese context. In M. J. Kane (Ed.), Contemporary issues in parenting (pp. 111–124). New York: Nova Science.

Lamb, M. E., & Lewis, C. (2010). The development and significance of father-child relationships in two-parent families. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (5th ed., pp. 94–153). New York: John Wiley.

Larzelere, R. E., & Mulaik, S. A. (1977). Single-sample tests for many correlations. Psychological Bulletin, 84(3), 557–569.

Leung, J. T. Y. (2017). Parent-adolescent discrepancies in perceived parental sacrifice and adolescent developmental outcomes in poor Chinese families. Journal of Research on Adolescence., 28, 520–536. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12356.

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2011a). “All I can do for my child” – development of the Chinese parental sacrifice for child’s education scale. International Journal of Disability and Human Development, 10, 201–208.

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2011b). Validation of the Chinese parental sacrifice for Child’s education scale. International Journal of Disability and Human Development, 10, 209–215.

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2013a). Are family processes related to achievement motivation of Chinese adolescents experiencing economic disadvantage in Hong Kong? International Journal of Disability and Human Development, 12, 115–125.

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2013b). Parenting for resilience: family processes and psychosocial competence of Chinese adolescents experiencing economic disadvantage in Hong Kong. International Journal on Disability and Human Development, 12, 127–137.

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2015). Parental beliefs and parental sacrifice of Chinese parents experiencing economic disadvantage in Hong Kong: Implications for social work. British Journal of Social Work, 45, 1119–1136.

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2016a). Family functioning, filial piety and adolescent psychosocial competence in Chinese single-mother families experiencing economic disadvantage: implications for social work. British Journal of Social Work, 46, 1809–1827.

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2016b). Parent-child discrepancies in perceived parental sacrifice and achievement motivation of Chinese adolescents experiencing economic disadvantage. Child Indicators Research, 9, 683–700.

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2016c). The influence of parental beliefs on the development of Chinese adolescents experiencing economic disadvantage: maternal control as a mediator. Journal of Family Issues, 37(4), 543–573.

Leung, J. T. Y., Shek, D. T. L., & Ma, C. M. S. (2016). Measuring perceived parental sacrifice among adolescents in Hong Kong: confirmatory factor analyses of the Chinese parental sacrifice scale. Child Indicators Research, 9, 173–192.

Linver, M. R., & Silverberg, S. B. (1997). Maternal predictors of early adolescent achievement-related outcomes: adolescent gender as moderator. Journal of Early Adolescence, 17, 294–318.

Lu, H. J., & Chang, L. (2013). Parenting and socialization of only children in urban China: an example of authoritative parenting. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 174(3), 335–343.

Mistry, R. S., Lowe, E. D., Benner, A. D., & Chien, N. (2008). Expanding the family economic stress model: insights from a mixed-methods approach. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70(1), 196–209.

Plunkett, S. W., Henry, C. S., Robinson, L. C., Behnke, A., & Falcon III, P. C. (2007). Adolescent perceptions of parental behaviors, adolescent self-esteem, and adolescent depressed mood. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16(6), 760–772.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891.

Rubin, A., & Babbie, E. R. (2017). Research methods for social work. Boston: Cengage Learning.

Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2010). Relationship between multiple sources of perceived social support and psychological and academic adjustment in early adolescence: comparisons across gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 47–61.

Russell, M., Harris, B., & Gockel, A. (2008). Parenting in poverty: perspectives of high-risk parents. Journal of Children and Poverty, 14(1), 83–98.

Shek, D. T. L. (1992). “Actual-ideal” discrepancies in the representation of self and significant-others and psychological well-being in Chinese adolescents. International Journal of Psychology, 27(3), 229.

Shek, D. T. L. (2006). Chinese family research: puzzles, progress, paradigms, and policy implications. Journal of Family Issues, 27(3), 275–284.

Shek, D. T. L. (2008). Economic disadvantage, perceived family quality of life, and emotional well-being in Chinese adolescents: a longitudinal study. Social Indicators Research, 85, 169–189.

Shek, D. T., & Lee, T. Y. (2007). Family life quality and emotional quality of life in Chinese adolescents with and without economic disadvantage. Social Indicators Research, 80(2), 393–410.

Solantaus, T., Leinonen, J., & Punamäki, R. L. (2004). Children’s mental health in times of economic recession: replication and extension of the family economic stress model in Finland. Developmental Psychology, 40(3), 412–429.

Stacey, J. (1983). Patriarchy and Socialist revolution in China. Berkeley: University of California.

Su, C., & Hynie, M. (2011). Effects of life stress, social support, and cultural norms on parenting styles among mainland Chinese, European Canadian, and Chinese Canadian immigrant mothers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42, 1–19.

Walsh, F. (2016). Strengthening family resilience. New York: Guilford.

Wang, M. T., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Social support matters: longitudinal effects of social support on three dimensions of school engagement from middle to high school. Child Development, 83(3), 877–895.

Yeh, K. H., & Bedford, O. (2003). A test of the dual filial piety model. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 6, 215–228.

Yeh, M. H., & Yang, K. S. (1997). Chinese familism: conceptual analysis and empirical assessment. Bulletin of the Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica (Taiwan), 83, 169–225 [in Chinese].

Yeh, K. H., Yi, C. C., Tsao, W. C., & Wan, P. S. (2013). Filial piety in contemporary Chinese societies: a comparative study of Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China. International Sociology, 28(3), 277–296.

Yoshikawa, H., Aber, J. L., & Beardslee, W. R. (2012). The effects of poverty on the mental, emotional, and behavioral health of children and youth: implications for prevention. American Psychologist, 67(4), 272–284.

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the Early Career Scheme, Research Grants Council (Project Code: PolyU 216008/15H). An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Society for Quality-of-Life Studies (ISQOLS) held at Innsbruck, Austria in September 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leung, J.T.Y., Shek, D.T.L. Parental Sacrifice, Filial Piety and Adolescent Life Satisfaction in Chinese Families Experiencing Economic Disadvantage. Applied Research Quality Life 15, 259–272 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9678-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9678-0