Abstract

Cognitive complications persist in antiretroviral therapy(ART)-treated people with HIV. However, the pattern and severity of domain-specific cognitive performance is variable and may be exacerbated by ART-mediated neurotoxicity. 929 women with HIV(WWH) from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study who were classified into subgroups based on sociodemographic and longitudinal behavioral and clinical data using semi-parametric latent class trajectory modelling. Five subgroups were comprised of: 1) well-controlled HIV with vascular comorbidities(n = 116); 2) profound HIV legacy effects(CD4 nadir <250 cells/μL; n = 275); 3) primarily <45 year olds with hepatitis C(n = 165); 4) primarily 35–55 year olds(n = 244), and 5) poorly-controlled HIV/substance use(n = 129). Within each subgroup, we fitted a constrained continuation ratio model via penalized maximum likelihood to examine adjusted associations between recent ART agents and cognition. Most drugs were not associated with cognition. However, among the few drugs, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTIs) and protease inhibitors(PIs) were most commonly associated with cognition, followed by nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors(NRTIs) and integrase inhibitors(IIs). Directionality of ART-cognition associations varied by subgroup. Better psychomotor speed and fluency were associated with ART for women with well-controlled HIV with vascular comorbidities. This pattern contrasts women with profound HIV legacy effects for whom poorer executive function and fluency were associated with ART. Motor function was associated with ART for younger WWH and primarily 35–55 year olds. Memory was associated with ART only for women with poorly-controlled HIV/substance abuse. Findings demonstrate interindividual variability in ART-cognition associations among WWH and highlight the importance of considering sociodemographic, clinical, and behavioral factors as an underlying contributors to cognition.

Are antiretroviral agents a risk factor for cognitive complications in women with HIV? We examind associations between ART-agents and cognitive function among similar subgroups of women with HIV from the Women's Interagency HIV study. The patterns of associations depended on sociodemographic, clinical, and behavioral characteristics of women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite substantive decreases in HIV-associated morbidity and mortality following effective antiretroviral therapy (ART), cognitive complications of the disease remain high. Approximately 30–60% of people with HIV (PWH) develop cognitive impairment (CI), with the majority experiencing milder forms (Grant 2008). Many thought that successful suppression of HIV with ART would eradicate HIV-related CI. However, investigations in large-scale cohort studies, such as the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) (Rubin et al. 2017) and others (Simioni et al. 2010; Su et al. 2017), show that CI persists despite viral suppression. Recent studies demonstrate considerable heterogeneity in cognition among PWH and HIV-uninfected individuals defined by unique patterns of domain-specific cognitive function (Brouillette et al. 2016; Rubin et al. 2017; Gomez et al. 2018; Molsberry et al. 2018; Dastgheyb et al. 2019). Understanding factors that contribute to patterns of domain-specific cognitive function is of critical importance to understand factors that contribute to CI.

ART agents continue to garner interest in the field of neuroHIV as potential contributors to CI. In vitro, animal, imaging, and clinical studies provide evidence that some ART agents may affect cognition (Robertson et al. 2012; Akay et al. 2014; Underwood et al. 2015; Zhuang et al. 2017). The non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) efavirenz (EFV) is commonly associated with cognitive function (Decloedt and Maartens 2013). However, evidence is lacking regarding the directionality and consistency of these associations among subsets of PWH. While some studies report associations between EFV and poorer cognitive function (Ciccarelli et al. 2011; Ma et al. 2016; Rubin et al. 2017) or less cognitive improvement (Winston et al. 2012), others report greater EFV-related cognitive benefits (Clifford et al. 2005, 2009; Robertson et al. 2010). Others have reported no effects of EFV on cognition (Li et al. 2019). Our previous studies also demonstrated variable patterns of ART-related cognitive change phenotypes in 312 PWH that were initially tested when ART-naïve and again 2 years after ART initiation (85% treated with EFV). We found ART-related domain-specific cognitive patterns of decline in 15% of participants, improvements in 20%, both improvements and declines in 10%, and no cognitive changes in 54% (Rubin et al. 2019). The results from these studies identified marked interindividual differences in the cognitive effects of medications. For example, the effects of ART agents, such as EFV, on cognition may differ based on: 1) biological sex; 2) age (e.g., age-related metabolic changes (Mangoni and Jackson 2004) and structural changes in blood brain barrier permeability (Erdo et al. 2017)); 3) genetic background (e.g., intestinal and hepatic CYP450 enzymes which impact drug metabolism (Zanger and Schwab 2013)); 4) host factors, including drug pharmacokinetics (Burger et al. 2006; Winston et al. 2013; Dhoro et al. 2015); 5) polypharmacy (ART and non-ART drug interactions); and 6) food intake, which may influence drug bioavailability. Together, these studies point to: 1) personalized medicine approaches in evaluating potential effects of ART on cognitive function and 2) acknowledging that ART may be beneficial, detrimental, or have no effect even when considering socio-demographic, clinical, and behavioral characteristics.

In this analysis, we examined associations between individual ART drugs and domain-specific cognitive function among subgroups of women with HIV (WWH). We focused on WWH as biological sex impacts the efficacy, mechanisms of actions, and ART-related adverse events (Feinberg 1993; Gandhi et al. 2004; Mangoni and Jackson 2004; Lee et al. 2014). We hypothesized that EFV would be associated with cognitive performance among subgroups of WWH. We also expected the following commonly used ART drugs in our sample to be associated with cognition because of their average-to much-above-average CNS penetration (Letendre et al. 2008; Letendre 2011) and because of their link to neuro- and/or mitochondrial toxicity (Schweinsburg et al. 2005; Robertson et al. 2012; Akay et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2015), cerebral function (Winston et al. 2010), and functional and structural brain connectivity (Zhuang et al. 2017): NNRTI nevirapine (NVP), nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) abacavir (ABC), didanosine (DDI), stavudine (d4T), zidovudine (ZDV), and protease inhibitor (PI) atazanavir (ATV).

Methods

Study Population

All participants were enrolled in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS); full details of the study design and prospective data collection are described in detail at https://statepi.jhsph.edu/wihs/wordpress/. The first three waves of study enrollment occurred between October 1994 and November 1995, October 2001 and September 2002, and January 2011 and January 2013 from six sites (Brooklyn, Bronx, Chicago, DC, Los Angeles, and San Francisco). A more recent wave of enrollment occurred at sites in the southern US (Chapel Hill, Atlanta, Miami, Birmingham, and Jackson) between October 2013 and September 2015. At semiannual visits, participants complete physical examinations, provide biological specimens, and undergo extensive assessment of clinical, behavioral, and demographic characteristics via face to-face interviews. A comprehensive neuropsychological test battery is administered every 2 years in conjunction with WIHS semiannual core study visits. The first neuropsychological testing occurred between 2009 and 2011.

We restricted participants in the present study to those with longitudinal data collected at all WIHS study visits where ART use and neuropsychological testing were collected. Participants were excluded from analysis if the ART regimen used “at study visit” and “since last study visit” (~ past 6 months) were discordant, as we wanted to ensure that participants were on the same ART drugs for at least 6 months. There were 599 observations out of 4900 (12%) excluded from the study, leaving 4301 observations for analysis with not all women contributing the same number of visits (mean number of visits per participant = 4.6; range 1 to 11).

Study Outcome: Cognitive Function

The neuropsychological test battery included the following tests: Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (HVLT-R; outcomes = total learning across trials, delayed free recall), Stroop Test (outcomes = time to completion on word reading trial [trial 1], color naming trial [trial 2], color-word interference trial [trial 3]), Trail Making Test (TMT) Parts A and B (outcomes = time to completion on each Parts A and B), Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT; outcome = total correct), Letter-Number Sequencing (LNS; outcomes = total correct on control and experimental condition), Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT; outcome = total words generated), category fluency (outcome = total words generated), and grooved pegboard (GPEG; outcome = time to completion on the dominant and non-dominant hand). All timed outcome measures were log transformed to normalize distributions and also reverse scored so that higher values represented higher performance. Demographically-adjusted T-scores [mean = 50, standard deviation = 10] were derived for each outcome; and T-scores were combined into six cognitive domains and motor function: learning, memory, attention/working memory, executive function, psychomotor speed, fluency, and motor skills (Maki et al. 2015; Rubin et al. 2017).

Covariates

The primary covariates of interest were based on prior knowledge of factors that influence cognitive function in WWH (Maki et al. 2015; Rubin et al. 2017). These included clinic site; enrollment wave; sociodemographic factors (age, race/ethnicity, years of education, employment status, average annual household income, and marital status); behavioral factors (smoking status, recent alcohol use, marijuana use, crack, cocaine, and/or heroin use); clinical factors (Hepatitis C antibody positive); and metabolic and cardiovascular factors (body mass index, hypertension, diabetes). HIV-related clinical factors included HIV RNA, current and nadir CD4 count, and previous AIDS diagnosis.

Statistical Analyses

For each subgroup that was identified from the larger sample (see supplemental materials for details on methods), we fitted a constrained continuation ratio (CCR) model via penalized maximum likelihood (via R package glmnetcr) using the ART use information as independent variables (X) as well as other covariates (e.g., age, BMI) and each cognitive domain as a dependent variable (Y). The Lasso penalty was used in the model to achieve better data fitting and prediction. We searched through a sequence of values to identify the best regularization parameter in the Lasso penalty through cross-validation. For robustness of the inference on associations of ART drug and cognitive function, we employed a bootstrap aggregation procedure to generate 100 bootstrapping datasets by randomly sampling half of the number of observations without replacement. For robustness of the inference on ART drug and cognitive domains and adjustment of multiple comparisons, we employed a bootstrap aggregation procedure to control the false discovery rate (FDR)(Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). Specifically, we generated 100 bootstrapping datasets by randomly sampling half of the number of observations without replacement. We then applied the CCR model to the 100 datasets separately and obtained significant drug-cognitive domains associations for each of the datasets. The association of a specific drug-domain item pair was designated as significant if that drug was selected as an important predictor for that cognitive domain item in at least 90% of the bootstrapped datasets.

Results

Overall Study Sample Characteristics and Subgroups of WWH

Our study sample included 929 WWH who contributed 4301 observations in the WIHS from October 2009 to April 2016. This subset of 929 women was similar in terms of socio-demographic, behavioral and clinical factors, and ART-regimens to the larger sample of 3434 participants (Williams et al. 2020). See Tables 1 and 2, and Supplemental Table 1 for participant characteristics.

Based on our previous analyses using 47,377 observations from the 3434 participants (Williams et al. 2020), we categorized this subset of 929 WWH as into one of five mutually exclusive subgroups based on their longitudinal data, which included socio-demographic, behavioral, and clinical factors. One hundred and sixteen women contributing 380 observations were in Subgroup 1 (controlled HIV [e.g., undetectable HIV RNA] with vascular comorbidities [hypertension, diabetes]); 275 women contributing 1488 observations were in Subgroup 2 (HIV legacy effects [e.g., CD4 nadir < 250]); 165 women contributing 937 observations were in Subgroup 3 (younger individuals [<45 years of age] with hepatitis C virus); 244 women contributing 1041 observations were in Subgroup 4 (primarily 36–55 year olds); and 129 women contributing 455 observations were in Subgroup 5 (substance use [crack, cocaine, and/or heroin, smoking] and poorly controlled HIV [CD4 nadir < 250, current CD4 < 250, HIV RNA > 5000 cp/mL]).

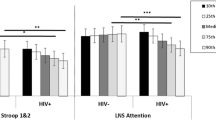

Cognitive Function among Subgroups of WWH

On average, each of the subgroups of women had domain-specific T-scores falling into the average range (mean ~50, SD = 10) (Table 3; Supplemental Fig. 1). However, the subgroups differed on the pattern of domain-specific cognitive impairment (1 standard deviation [SD] below the T-score mean of the HIV-uninfected WIHS women) (Supplemental Fig. 1). Women with controlled HIV with vascular comorbidities (Subgroup 1) demonstrated the greatest impairment on memory (versus all other groups). In contrast, women with profound HIV legacy effects (Subgroup 2) had the greatest impairment in executive function. Women primarily 36–55 years of age (Subgroup 4) had the greatest impairment in fluency and motor function. Substance users with poorly controlled HIV (Subgroup 5) had impaired psychomotor speed. Finally, women primarily <45 years of age (Subgroup 3) demonstrated the least impairment on memory and attention/working memory (versus other groups).

Associations between Individual ART Drugs and Cognitive Function in Subgroups of WWH

Figure 1 provides the results of the associations between ART drug and cognition in subgroups of WWH. Blue lines indicate better cognitive performance, while red lines indicate poorer performance. The weight of the line indicates the magnitude of the association. Table 4 provides the magnitude of the associations (or edge weight) between ART and domain-specific cognitive function (continuous T-scores) among subgroups of WWH, whereby a positive edge weight is associated with improved cognition and a negative edge indicates that the ART drug is associated with poorer cognitive function. Although all ART agents were included in the models, we focused on ART drugs being used >5% in the overall sample. Most ART drugs were not associated with cognition. However, among the few that were, NNRTI’s (NVP, rilpivirine [RPV], EFV) and PI’s (ATV, NFV, darunavir [DRV]) were most commonly associated with cognition, followed by NRTI’s (DDI, ZDV) and II’s (raltegravir [RAL], DTG). Despite these associations, the directionality of ART-cognition associations varied substantially by subgroup.

Associations between ART drugs and domain-specific cognitive function in subgroups of women with HIV (WWH). Blue lines indicate that the ART drug is associated with better cognition and red lines indicate that the ART type is associated with poorer cognition. The weight of the line indicates the magnitude of the association. The circle colors reflect the ART agent type (e.g., integrase inhibitor, etc). NRTI nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors; NNRTI non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor; II integrase inhibitor; PI protease inhibitor.

Psychomotor speed and fluency were most commonly associated with ART for women with well-controlled HIV with vascular comorbidities (Subgroup 1). NVP was the only ART drug associated with cognition for women in this subgroup. Interestingly, NVP was associated with better psychomotor speed (9 point higher T-score, ~1 SD) and better fluency (8 point higher T-score; ~1 SD) (Table 4, Fig. 1a).

In addition to fluency, executive function was also most commonly associated with ART for women with profound HIV legacy effects (Subgroup 2). WWH in this subgroup exhibited both positive and inverse associations among ART agents and cognition (Table 4, Fig. 1b). Specifically, ZDV was associated with better executive function. However, not all ART drugs were positively associated with cognition, as DDI was associated with poorer fluency (−5 point lower T-score) and RAL with poorer executive function.

Motor function was associated with ART exclusively for younger WWH (Subgroup 3) and primarily 35–55 year olds (Subgroup 4). Similar to what occurred in those with HIV legacy effects (Subgroup 2), Subgroups 3 and 4 had both positive and inverse associations between type of ART drugs and motor function (Table 4, Fig. 1c–d). Specifically, in Subgroup 3, ATV was associated with poorer motor function, while EFV was associated with better motor function. In Subgroup 4, ZDV and DRV were associated with poorer motor function, whereas ATV and NFV were associated with better motor function. DTG was also associated with better motor function for WWH in Subgroup 4.

Interestingly, memory was uniquely associated with ART only for women with poorly-controlled HIV and substance use (Subgroup 5). In contrast to all of the other subgroups, memory was the only domain associated with ART agents (Table 4, Fig. 1e). ATV (−11 point lower T score) was associated with a one SD lower score on memory, whereas RAL was associated with better memory.

Discussion

In these analyses, we utilized a bootstrap aggregation procedure to evaluate associations between ART drugs and cognitive function among subgroups of WWH and found that the direction and magnitude of associations between ART agents and domain-specific cognitive function is highly dependent on socio-demographic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics. Motor function was the domain most frequently associated with ART, which occurred for women in two of 5 subgroups (Subgroups 3 and 4). Fluency (Subgroups 1 and 2) and executive function (Subgroups 2 and 3) were the only cognitive domains that were associated with ART across multiple subgroups. This finding suggests that the neural circuitry regulating motor function, fluency, and executive function may be particularly sensitive to ART. Despite these common associations across subgroups, the individual drugs for which these associations occurred differed substantially. For example, executive function was associated with ZDV (NRTI) and RAL (II) for women in Subgroup 2, and with RPV (NNRTI) for women in Subgroup 3. It is important to note that there were no associations between individual ART drugs and any cognitive domain that occurred consistently among all of the subgroups. In fact, we identified psychomotor speed (Subgroup 1) and memory (Subgroup 5) as cognitive domains showing highly specific associations with ART. These findings provide insight into the multifactorial nature of the impact of ART on cognition and demonstrate that associations obtained from individual sociodemographic, phenotypic or clinical subgroups are not necessarily generalizable– even among individuals enrolled in the same study. These findings may explain, in part, inconsistencies in the observed associations between ART and cognitive function reported in the literature.

Our data also warn against the generalization of individual ART drugs when evaluating associations with cognitive function. ART agents, even those within the same drug class, are distinct pharmacologic entities with different pharmacokinetics, half-lives, and molecular structures that may each have unique impacts on physiological functions unrelated to their effects on HIV. Our findings demonstrated that it is possible for only one ART drug in a particular class to have an association with domain-specific cognitive function. As a result, we propose that the nuances of individual ART drugs needs to be considered when determining associations of ART and cognition among heterogeneous groups of PWH/WWH.

When evaluating individual ART drugs across subgroups, the most common ART agents associated with cognitive function included: ATV (PI; 3 of 5 subgroups), DDI and ZDV (NRTIs; 2 of 5 subgroups), and RAL (II; 2 of 5 subgroups). The CNS penetrance efficacy (CPE) scores (Letendre 2011) and the toxic potentials of these ART drugs may contribute to their associations with cognitive function. ATZ has an average CPE (Letendre 2011) and is toxic to neurons (Robertson et al. 2012). Consistent with this notion, we found that ATV was associated with poorer memory performance among WWH who were substance users with poorly controlled HIV (Subgroup 5, ~1 SD), and among younger women with Hepatitis C (Subgroup 3, 0.2 SD). In contrast, ATV was associated with better motor function (0.2 SD) among middle-aged women (Subgroup 4), who did not abuse recreational drugs, and were virologically controlled. DDI also has an average CPE (Letendre 2011) and has been associated with reductions in neuronal integrity (Winston et al. 2010) and mitochondrial toxicity (Schweinsburg et al. 2005). These previous data are consistent with our findings showing that DDI relates to poorer attention/working memory (~1/2 SD) among younger women with hepatitis C (Subgroup 3) and poorer fluency (~0.5 SD) among women with profound HIV legacy effects (Subgroup 2). ZDV has a much higher than average CPE (Letendre 2011) and yet showed both negative (lower motor among middle-aged women) and positive associations (higher executive function among those with profound HIV legacy effects) with cognitive function. These findings are in part consistent with a number of studies demonstrating that ZDV induces both neural and mitochondrial dysfunction (Kline et al. 2009; Giunta et al. 2011), and other studies demonstrating cognitive benefits (Portegies et al. 1989; Tozzi et al. 1993; Winston et al. 2010). RAL has an above average CPE (Letendre 2011) and has been associated with CNS symptoms (Madeddu et al. 2012), consistent with our findings that show associations of RAL in women with legacy effects (poorer executive function) and lack of association in women with substance use and poorly controlled HIV (better memory).

Alternatively the different pattern of drug-cognition associations among subgroups may also be explained by inter-individual variability in pharmacokinetic profiles or genetic considerations. For example, while RAL is estimated to have a high CPE, calculations used to derive CPE do not consider these individual differences (Brainard et al. 2011). CSF-to-plasma RAL concentration ratios vary as much as 50-fold between individuals (Yilmaz et al. 2009; Croteau et al. 2010). RAL is also a substrate for drug efflux transporters that are highly polymorphic, particularly among African-Americans which is the majority of our cohort, which can greatly affects its’ CSF concentrations (Hoffmeyer et al. 2000; Chinn and Kroetz 2007; Hoque et al. 2015). Other biological considerations, including bilirubin levels, impact RAL (Arab-Alameddine et al. 2012). Thus, it may be possible that these inter-individual differences exist among our subgroups which may not be explained by CPE.

Additionally, other ART agents associated with cognitive function in at least one group included the following NNRTIs (NVP, RPV), PIs (DRV, NFV), and IIs (DTG). Among the NNRTIs, NVP has a higher than average CPE whereas ETR and RPV has an average CPE (Letendre 2011). NVP has been shown to have a high risk of neurotoxic effects (Streck et al. 2008; Robertson et al. 2012), yet we found that NVP was associated with better processing speed and fluency among women with controlled HIV and vascular comorbidities (Subgroup 1). Among the PIs, DRV has above average CPEs, whereas NFV has a below average CPE (Letendre 2011). DRV was associated with poorer motor function (subgroup 4), whereas NFV (subgroup 4) was associated with better motor function. Unexpectedly, EFV was not widely associated with cognitive function. In fact, EFV was associated with better motor function for one subgroup (younger women with hepatitis C). The association of EFV with higher NP function in our study is consistent with some (Clifford et al. 2005; Clifford et al. 2009; Robertson et al. 2010) but not all studies (Streck et al. 2008; Ciccarelli et al. 2011; Winston et al. 2012; Ma et al. 2016; Rubin et al. 2017; Li et al. 2020).

Limitations of our analyses include a cross-sectional approach to examining the associations of ART drugs on cognition. Thus, we are unable to provide mechanistic insight as to why specific subgroups demonstrated specific ART-domain-specific cognitive associations compared to other subgroups. Additionally, our focus was on specific ART agents rather than examining standard drug combinations. New analytic methods are currently under development to address both of these issues. Other limitations include the availability of certain ART agents over the longitudinal course of WIHS which confines the clinical applicability of the findings. For example, given the time span of the study not all WWH at all visits had the opportunity to be evaluated on all of the ART agents. This concern is somewhat mitigated as the distribution of enrollment periods and follow-up time/dropout was not substantially different between the identified cluster groups. Additionally, our findings are only generalizable to WWH and the pattern of associations may not be the same among men with HIV which we plan to examine in future analyses.

In summary, we took a novel approach to evaluate the impact of ART on cognition in WWH. Through our analysis of five subgroups, we determined that, as a whole, fluency, executive function, and motor function were most frequently associated with ART. However, the individual ART drugs and the direction of the association were highly dependent on the subgroup of WWH evaluated. There was no association with any ART drug that occurred for all subgroups, highlighting the importance of evaluating the heterogeneous impact of ART on cognitive function. Our findings provide insight into a precision medicine based approach that may be useful to mitigate the potential neurotoxic effects of ART by considering the unique socio-demographic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics of an individual when prescribing a treatment regimen.

References

Akay C et al (2014) Antiretroviral drugs induce oxidative stress and neuronal damage in the central nervous system. J Neuro-Oncol 20:39–53

Arab-Alameddine M, Fayet-Mello A, Lubomirov R, Neely M, di Iulio J, Owen A, Boffito M, Cavassini M, Gunthard HF, Rentsch K, Buclin T, Aouri M, Telenti A, Decosterd LA, Rotger M, Csajka C, Swiss HIVCSG (2012) Population pharmacokinetic analysis and pharmacogenetics of raltegravir in HIV-positive and healthy individuals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:2959–2966

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B 57:125–133

Brainard DM, Wenning LA, Stone JA, Wagner JA, Iwamoto M (2011) Clinical pharmacology profile of raltegravir, an HIV-1 integrase strand transfer inhibitor. J Clin Pharmacol 51:1376–1402

Brouillette MJ, Yuen T, Fellows LK, Cysique LA, Heaton RK, Mayo NE (2016) Identifying neurocognitive decline at 36 months among HIV-positive participants in the CHARTER cohort using group-based trajectory analysis. PLoS One 11:e0155766

Burger D, van der Heiden I, la Porte C, van der Ende M, Groeneveld P, Richter C, Koopmans P, Kroon F, Sprenger H, Lindemans J, Schenk P, van Schaik R (2006) Interpatient variability in the pharmacokinetics of the HIV non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor efavirenz: the effect of gender, race, and CYP2B6 polymorphism. Br J Clin Pharmacol 61:148–154

Chinn LW, Kroetz DL (2007) ABCB1 pharmacogenetics: progress, pitfalls, and promise. Clin Pharmacol Ther 81:265–269

Ciccarelli N, Fabbiani M, Di Giambenedetto S, Fanti I, Baldonero E, Bracciale L, Tamburrini E, Cauda R, De Luca A, Silveri MC (2011) Efavirenz associated with cognitive disorders in otherwise asymptomatic HIV-infected patients. Neurology 76:1403–1409

Clifford DB, Evans S, Yang Y, Acosta EP, Goodkin K, Tashima K, Simpson D, Dorfman D, Ribaudo H, Gulick RM (2005) Impact of efavirenz on neuropsychological performance and symptoms in HIV-infected individuals. Ann Intern Med 143:714–721

Clifford DB, Evans S, Yang Y, Acosta EP, Ribaudo H, Gulick RM, As Study T (2009) Long-term impact of efavirenz on neuropsychological performance and symptoms in HIV-infected individuals (ACTG 5097s). HIV Clin Trials 10:343–355

Croteau D, Letendre S, Best BM, Ellis RJ, Breidinger S, Clifford D, Collier A, Gelman B, Marra C, Mbeo G, Mc Cutchan A, Morgello S, Simpson D, Way L, Vaida F, Ueland S, Capparelli E, Grant I, Group C (2010) Total raltegravir concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid exceed the 50-percent inhibitory concentration for wild-type HIV-1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:5156–5160

Dastgheyb RM, Sacktor N, Franklin D, Letendre S, Marcotte T, Heaton R, Grant I, McArthur J, Rubin LH, Haughey NJ (2019) Cognitive trajectory phenotypes in human immunodeficiency virus infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr

Decloedt EH, Maartens G (2013) Neuronal toxicity of efavirenz: a systematic review. Expert Opin Drug Saf 12:841–846

Dhoro M, Zvada S, Ngara B, Nhachi C, Kadzirange G, Chonzi P, Masimirembwa C (2015) CYP2B6*6, CYP2B6*18, body weight and sex are predictors of efavirenz pharmacokinetics and treatment response: population pharmacokinetic modeling in an HIV/AIDS and TB cohort in Zimbabwe. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 16:4

Erdo F, Denes L, de Lange E (2017) Age-associated physiological and pathological changes at the blood-brain barrier: a review. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 37:4–24

Feinberg M (1993) The problems of anticholinergic adverse effects in older patients. Drugs Aging 3:335–348

Gandhi M, Aweeka F, Greenblatt RM, Blaschke TF (2004) Sex differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 44:499–523

Giunta B, Ehrhart J, Obregon DF, Lam L, Le L, Jin J, Fernandez F, Tan J, Shytle RD (2011) Antiretroviral medications disrupt microglial phagocytosis of beta-amyloid and increase its production by neurons: implications for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Mol Brain 4:23

Gomez D, Power C, Gill MJ, Koenig N, Vega R, Fujiwara E (2018) Empiric neurocognitive performance profile discovery and interpretation in HIV infection. J Neuro-Oncol

Grant I (2008) Neurocognitive disturbances in HIV. Int Rev Psychiatry 20:33–47

Hoffmeyer S, Burk O, von Richter O, Arnold HP, Brockmoller J, Johne A, Cascorbi I, Gerloff T, Roots I, Eichelbaum M, Brinkmann U (2000) Functional polymorphisms of the human multidrug-resistance gene: multiple sequence variations and correlation of one allele with P-glycoprotein expression and activity in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:3473–3478

Hoque MT, Kis O, De Rosa MF, Bendayan R (2015) Raltegravir permeability across blood-tissue barriers and the potential role of drug efflux transporters. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:2572–2582

Kline ER, Bassit L, Hernandez-Santiago BI, Detorio MA, Liang B, Kleinhenz DJ, Walp ER, Dikalov S, Jones DP, Schinazi RF, Sutliff RL (2009) Long-term exposure to AZT, but not d4T, increases endothelial cell oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Cardiovasc Toxicol 9:1–12

Lee JW, Aminkeng F, Bhavsar AP, Shaw K, Carleton BC, Hayden MR, Ross CJ (2014) The emerging era of pharmacogenomics: current successes, future potential, and challenges. Clin Genet 86:21–28

Letendre S (2011) Central nervous system complications in HIV disease: HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. Top Antivir Med 19:137–142

Letendre S, Marquie-Beck J, Capparelli E, Best B, Clifford D, Collier AC, Gelman BB, McArthur JC, McCutchan JA, Morgello S, Simpson D, Grant I, Ellis RJ (2008) Validation of the CNS penetration-effectiveness rank for quantifying antiretroviral penetration into the central nervous system. Arch Neurol 65:65–70

Li Y, Wang Z, Cheng Y, Becker JT, Martin E, Levine A, Rubin LH, Sacktor N, Ragin A, Ho K (2019) Neuropsychological changes in efavirenz switch regimens. AIDS 33:1307–1314

Li Y, Wang Z, Cheng Y, Becker J, Martin E, Levine A, Rubin LH, Sacktor N, Ragin A, Ho K (2020) Neuropsychological changes in efavirenz switch regimens in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. AIDS

Ma Q, Vaida F, Wong J, Sanders CA, Kao YT, Croteau D, Clifford DB, Collier AC, Gelman BB, Marra CM, JC MA, Morgello S, Simpson DM, Heaton RK, Grant I, Letendre SL, Group C (2016) Long-term efavirenz use is associated with worse neurocognitive functioning in HIV-infected patients. J Neuro-Oncol 22:170–178

Madeddu G, Menzaghi B, Ricci E, Carenzi L, Martinelli C, di Biagio A, Parruti G, Orofino G, Mura MS, Bonfanti P, Group CISAI (2012) Raltegravir central nervous system tolerability in clinical practice: results from a multicenter observational study. AIDS 26:2412–2415

Maki PM, Rubin LH, Valcour V, Martin E, Crystal H, Young M, Weber KM, Manly J, Richardson J, Alden C, Anastos K (2015) Cognitive function in women with HIV: findings from the Women's Interagency HIV study. Neurology 84:231–240

Mangoni AA, Jackson SH (2004) Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: basic principles and practical applications. Br J Clin Pharmacol 57:6–14

Molsberry SA, Cheng Y, Kingsley L, Jacobson L, Levine AJ, Martin E, Miller EN, Munro CA, Ragin A, Sacktor N, Becker JT, Neuropsychology Working Group of the Multicenter ACS (2018) Neuropsychological phenotypes among men with and without HIV disease in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. AIDS 32:1679–1688

Portegies P, de Gans J, Lange JM, Derix MM, Speelman H, Bakker M, Danner SA, Goudsmit J (1989) Declining incidence of AIDS dementia complex after introduction of zidovudine treatment. BMJ 299:819–821

Robertson KR, Su Z, Margolis DM, Krambrink A, Havlir DV, Evans S, Skiest DJ, Team AS (2010) Neurocognitive effects of treatment interruption in stable HIV-positive patients in an observational cohort. Neurology 74:1260–1266

Robertson K, Liner J, Meeker RB (2012) Antiretroviral neurotoxicity. J Neuro-Oncol 18:388–399

Rubin LH, Maki PM, Springer G, Benning L, Anastos K, Gustafson D, Villacres MC, Jiang X, Adimora AA, Waldrop-Valverde D, Vance DE, Bolivar H, Alden C, Martin EM, Valcour VG, Women's Interagency HIVS (2017) Cognitive trajectories over 4 years among HIV-infected women with optimal viral suppression. Neurology 89:1594–1603

Rubin LH, Saylor D, Nakigozi G, Nakasujja N, Robertson K, Kisakye A, Batte J, Mayanja R, Anok A, Lofgren SM, Boulware DR, Dastgheyb R, Reynolds SJ, Quinn TC, Gray RH, Wawer MJ, Sacktor N (2019) Heterogeneity in neurocognitive change trajectories among people with HIV starting antiretroviral therapy in Rakai, Uganda. J Neuro-Oncol

Schweinsburg BC, Taylor MJ, Alhassoon OM, Gonzalez R, Brown GG, Ellis RJ, Letendre S, Videen JS, JA MC, Patterson TL, Grant I, Group H (2005) Brain mitochondrial injury in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive (HIV+) individuals taking nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. J Neuro-Oncol 11:356–364

Simioni S, Cavassini M, Annoni JM, Rimbault Abraham A, Bourquin I, Schiffer V, Calmy A, Chave JP, Giacobini E, Hirschel B, Du Pasquier RA (2010) Cognitive dysfunction in HIV patients despite long-standing suppression of viremia. AIDS 24:1243–1250

Streck EL, Scaini G, Rezin GT, Moreira J, Fochesato CM, Romao PR (2008) Effects of the HIV treatment drugs nevirapine and efavirenz on brain creatine kinase activity. Metab Brain Dis 23:485–492

Su T, Mutsaerts HJ, Caan MW, Wit FW, Schouten J, Geurtsen GJ, Sharp DJ, Prins M, Richard E, Portegies P, Reiss P, Majoie CB, Study AGC (2017) Cerebral blood flow and cognitive function in HIV-infected men with sustained suppressed viremia on combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 31:847–856

Tozzi V, Narciso P, Galgani S, Sette P, Balestra P, Gerace C, Pau FM, Pigorini F, Volpini V, Camporiondo MP et al (1993) Effects of zidovudine in 30 patients with mild to end-stage AIDS dementia complex. AIDS 7:683–692

Underwood J, Robertson KR, Winston A (2015) Could antiretroviral neurotoxicity play a role in the pathogenesis of cognitive impairment in treated HIV disease? AIDS 29:253–261

Williams DW, Li Y, Dastgheyb R, Fitzgerald KC, Maki PM, Spence AB, Gustafson DR, Milam J, Sharma A, Adimora AA, Ofotokun I, Fischl MA, Konkle-Parker D, Weber KM, Xu Y, R LH (2020) Associations between antiretroviral drugs on depressive symptomatology in homogenous subgroups of women with HIV. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology

Winston A, Duncombe C, Li PC, Gill JM, Kerr SJ, Puls R, Petoumenos K, Taylor-Robinson SD, Emery S, Cooper DA, Altair Study G (2010) Does choice of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) alter changes in cerebral function testing after 48 weeks in treatment-naive, HIV-1-infected individuals commencing cART? A randomized, controlled study. Clin Infect Dis 50:920–929

Winston A, Puls R, Kerr SJ, Duncombe C, Li PC, Gill JM, Taylor-Robinson SD, Emery S, Cooper DA, Altair Study G (2012) Dynamics of cognitive change in HIV-infected individuals commencing three different initial antiretroviral regimens: a randomized, controlled study. HIV Med 13:245–251

Winston A et al (2013) Effects of age on antiretroviral plasma drug concentration in HIV-infected subjects undergoing routine therapeutic drug monitoring. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:1354–1359

Yilmaz A, Gisslen M, Spudich S, Lee E, Jayewardene A, Aweeka F, Price RW (2009) Raltegravir cerebrospinal fluid concentrations in HIV-1 infection. PLoS One 4:e6877

Zanger UM, Schwab M (2013) Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol Ther 138:103–141

Zhang Y, Song F, Gao Z, Ding W, Qiao L, Yang S, Chen X, Jin R, Chen D (2014) Long-term exposure of mice to nucleoside analogues disrupts mitochondrial DNA maintenance in cortical neurons. PLoS One 9:e85637

Zhang Y, Wang B, Liang Q, Qiao L, Xu B, Zhang H, Yang S, Chen J, Guo H, Wu J, Chen D (2015) Mitochondrial DNA D-loop AG/TC transition mutation in cortical neurons of mice after long-term exposure to nucleoside analogues. J Neuro-Oncol 21:500–507

Zhuang Y, Qiu X, Wang L, Ma Q, Mapstone M, Luque A, Weber M, Tivarus M, Miller E, Arduino RC, Zhong J, Schifitto G (2017) Combination antiretroviral therapy improves cognitive performance and functional connectivity in treatment-naive HIV-infected individuals. J Neuro-Oncol 23:704–712

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Johns Hopkins University NIMH Center for novel therapeutics for HIV-associated cognitive disorders (P30MH075773) 2018 pilot award to Dr. Rubin, the Johns Hopkins University Center for AIDS Research NIH/NIAID fund (P30AI094189) 2019 faculty development award to Dr. Xu, and NSF DMS1918854 to Drs. Xu and Rubin. Dr. Williams effort was supported by K99DA044838. Data in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), now the MACS/WIHS Combined Cohort Study (MWCCS). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). MWCCS (Principal Investigators): Atlanta CRS (Ighovwerha Ofotokun, Anandi Sheth, and Gina Wingood), U01-HL146241; Baltimore CRS (Todd Brown and Joseph Margolick), U01-HL146241; Bronx CRS (Kathryn Anastos and Anjali Sharma), U01-HL146204; Brooklyn CRS (Deborah Gustafson and Tracey Wilson), U01-HL146202; Data Analysis and Coordination Center (Gypsyamber D'Souza, Stephen Gange, and Elizabeth Golub), U01-HL146193; Chicago-Cook County CRS (Mardge Cohen and Audrey French), U01-HL146245; Chicago-Northwestern CRS (Steven Wolinsky), U01-HL146240); Connie Wofsy Women's HIV Study, Northern California CRS (Bradley Aouizerat and Phyllis Tien), U01-HL146242; Los Angeles CRS (Roger Detels), U01-HL146333; Metropolitan Washington CRS (Seble Kassaye and Daniel Merenstein), U01-HL146205; Miami CRS (Maria Alcaide, Margaret Fischl, and Deborah Jones), U01-HL146203; Pittsburgh CRS (Jeremy Martinson and Charles Rinaldo), U01-HL146208; UAB-MS CRS (Mirjam-Colette Kempf and Deborah Konkle-Parker), U01-HL146192; UNC CRS (Adora Adimora), U01-HL146194. The MWCCS is funded primarily by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), with additional co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), National Institute on Aging (NIA), National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Kidne Diseases (NIDDK). MWCCS data collection is also supported by UL1-TR000004 (UCSF CTSA), P3-=AI-050409 (Atlanta CFAR), P30-AI-050410 (UNC CFAR), and P30-AI-027767 (UAB CFAR).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Rubin conceived the study idea and wrote the first draft of the manuscript with Drs. Xu and Williams and Mr. Li. Dr. Xu and Mr. Li take responsibility for the integrity of the statistical analyses. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

AS has received funding from Gilead Sciences, Inc. for unrelated work. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 222 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rubin, L.H., Li, Y., Fitzgerald, K.C. et al. Associations between Antiretrovirals and Cognitive Function in Women with HIV. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 16, 195–206 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11481-020-09910-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11481-020-09910-1