Abstract

Strategies such as behavioural substitution, self-monitoring, social support as well as planning and urge management can assist gamblers to limit or reduce their gambling behaviours. Not all gamblers implement strategies before, during or after gambling, even though the use of strategies is recommended by the gambling and treatment industry. Australian gamblers completed an online survey with follow-up (n = 411) to determine the predictors of intention to use strategies and the actual use of strategies. Results indicated 92% of gamblers attempted at least one strategy to stick to their limits over the 30-day period (median = 30 strategies, IQR = 11 to 56). Gamblers indicated a positive attitude towards strategy engagement and perceived themselves as having control over their use but the role that important others (e.g., family members) could play in strategy implementation warrants further examination. To improve strategy engagement, prevention and intervention programmes should target factors associated with intentions rather than focusing on behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Internationally, standardised prevalence rates of problem gambling range from 0.5 to 7.6%, with an average rate across all countries of 2.3% (Williams et al. 2012). In Australia, the prevalence of people with any level of gambling problem is estimated at 7.9% of the population, inclusive of 1% who are classified as problem gamblers (Armstrong and Carroll 2017). Although problem gambling is a relatively low base-rate phenomenon, it is estimated that over 1.3 million people in Australia are harmed by gambling behaviours (Armstrong and Carroll 2017). Browne et al. (2016) report that at a population-level, 85% of the burden of harm is experienced by people classified as low- or moderate-risk gambling (due to their greater prevalence in the population). The negative sequelae of gambling problems can include financial harm, relationship dysfunction and conflict, emotional distress, health decrements, cultural harm, reduced work or study performance and criminal activity (Langham et al. 2016).

To limit or reduce gambling-related harm, a range of cognitive and behavioural strategies have been recommended to gamblers by government and the gaming industry. Top-down strategies are those delivered as part of ‘responsible gambling (RG)’, ‘consumer protection’ or ‘harm minimisation’ programmes (Blaszczynski et al. 2011; Rodda et al. 2019a). These are industry or government initiated and are focused on the prevention of problems as well as assisting gamblers to stick to their limits (Ladouceur et al. 2017). Even though the use of tools offered by industry such as pre-commitment programmes or online deposit limits are helpful in sticking to limits, few gamblers make use of these tools (Procter et al. 2019). Strategies to avoid or reduce harm are also initiated by the gambler (referred to as protective behavioural strategies) (Lostutter et al. 2014). Compared with industry-initiated strategies, protective behavioural strategies are more a bottom-up approach whereby the gambler implements specific strategies immediately before or during a gambling session (Rodda et al. 2019a). Lostutter and colleagues (Lostutter et al. 2014) reported the more protective behavioural strategies that were implemented, the greater the reduction in gambling expenditure (Lostutter et al. 2014).

Cognitive and behavioural strategies are also initiated by gamblers as a means of reducing or regaining control over their gambling (Hing et al. 2017; Hodgins and el-Guebaly 2000; Matheson et al. 2019; Moore and Ohtsuka 1999; Rodda et al. 2018a). Similar to RG and protective behavioural strategies, gamblers attempting to reduce or regain control over their gambling also use in-venue strategies (e.g., limit setting) as well as pre-venue strategies (e.g., planning expenditure) but they also use a broad range of other strategies so as to avoid unwanted gambling altogether. These strategies include cognitive approaches such as considering the pros and cons of gambling, making a resolution to change, using willpower, thinking about how money could be better spent and identifying inaccurate thoughts about gambling (Rodda et al. 2018a). While cognitive strategies are most frequently used (Rodda et al. 2018a), behavioural strategies are more extensive and diverse (Hing et al. 2011; Hodgins and el-Guebaly 2000; Moore et al. 2012; Rodda et al. 2018a, b, c). For example, gamblers report limiting or reducing their gambling by using behaviour substitution (e.g., exercise instead of gambling), stimulus control (e.g., avoid venues), financial management (e.g., limit access to ready cash), social support (e.g., ask others to support change) and urge management (e.g., postpone gambling).

Gamblers on occasions bet more than intended, and this tendency is reported across all levels of gambling problems (from low-risk to problem gambling) (Cowlishaw et al. 2018). To mitigate this problem, cognitive and behavioural strategies are used as a way of sticking to limits, but to date, there has been limited research investigating the effectiveness of these strategies. There has, however, been multiple studies reporting the perceived helpfulness of strategies in terms of sticking to limits in venues (Abbott et al. 2014; Forsström et al. 2017; Lubman et al. 2015; Rodda et al. 2019a) and also reducing gambling once it becomes problematic (Hing et al. 2011; Hodgins and el-Guebaly 2000; Moore et al. 2012; Rodda et al. 2018a). Non-problem and low- and moderate-risk gamblers more frequently use strategies to stay in control than problem gamblers (Hing et al. 2017). In contrast when asked about strategies for limiting or reducing gambling, the number of strategies increases as a function of the level of gambling problems (Moore et al. 2012; Rodda et al. 2018a). Similarly, the use of strategies is also related to readiness to reduce gambling whereby the number of strategies used increases with level of readiness (Rodda et al. 2018a).

Despite the likelihood that implementing at least one strategy to limit or reduce gambling reduces harm, there has been limited research on the correlates of strategy use. Multiple studies have called for more information on the influences on the uptake of strategies as well as correlates of strategy abandonment (Matheson et al. 2019; Rodda et al. 2017, 2019a). Triggers to strategy engagement include concerns that the problem will worsen, negative emotions that have arisen because of gambling and financial concerns (Hing et al. 2011; Lubman et al. 2015) as well as a realisation that gambling had caused a significant change in the individual (Kim et al. 2017). Two studies specifically looking at RG measures have indicated the uptake of strategies is dependent on a range of factors including attitudes towards use (Forsström et al. 2017; Procter et al. 2019) but this research is yet to extend to the broader range of strategies or beyond internet-based gambling. Multiple studies indicate social support is a frequently used strategy, especially for reducing gambling harm (Hing et al. 2011; Hodgins and el-Guebaly 2000; Rodda et al. 2017, 2018a, c), but to date, there has been no investigation of how the influence of others may impact on the uptake of strategies. Another study explored the association between strategy uptake and self-efficacy (specifically to resist an urge to gamble) (Rodda et al. 2018a). This study reported weak relationships and called for more investigation into the influence of self-efficacy on strategy use. Taken together, these findings suggest an urgency for moving beyond a simple focus on the uptake or helpfulness of strategies to limit or reduce gambling and a more nuanced approach towards understanding factors that influence engagement. This approach includes an understanding of gamblers’ attitudes, social pressure and self-efficacy that may impact their decision to implement a strategy to limit or reduce gambling behaviours.

Theory of Planned Behaviour and Gambling

A theory that may help explain strategy engagement is the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) (Ajzen 1991). The TPB is well-validated and is widely used across various health behaviours (Armitage and Conner 2001; Conner et al. 2015; Godin and Kok 1996). According to the TPB, the most proximal predictor of behaviour is intention to perform that behaviour, with intention predicted by three distal (to behaviour) determinants: (i) positive or negative attitudes towards gambling (attitude), (ii) perceptions of social (e.g., family and friends) approval or disapproval towards gambling (subjective norm) and (iii) perceptions of how much control the person has over the behaviour, even when there are internal or external barriers (perceived behavioural control (PBC)). In terms of gambling, the TPB has been applied to predict intentions to gamble (Dahl et al. 2018; Flack and Morris 2017; Martin et al. 2010; Moore and Ohtsuka 1999; St-Pierre et al. 2015; Wu and Tang 2012), with intentions found to predict frequency of gambling, gambling expenditure, negative consequences and levels of problem gambling. Depending on the behaviour in focus, PBC may be a positive (e.g., belief in ability to beat the odds) (Flack and Morris 2017) or a negative predictor (e.g., belief in ability to stay in control when around gambling) of intention to gamble (St-Pierre et al. 2015; Wu and Tang 2012). Consistent with other behaviours, subjective norm has typically been the weakest variable in predicting gambling intentions. For instance, St-Pierre et al. (2015) reported subjective norms were not associated with gambling intentions. Few explorations have included demographics such as age and gender as well as gambling severity. When included, one study reported males, younger age and a low level of gambling severity were associated with more positive attitudes towards gambling (Salonen et al. 2014). Although yet to be examined within gambling, severity also appears to influence the explanatory pathways within the TPB. For instance, Cooke et al. (2016) reported PBC directly predicted alcohol consumption among problem drinkers (but not intentions), whereas intentions and not PBC directly predicted consumption among non-problem drinkers.

To date, gambling research using the TPB has predominantly focused on predicting intentions to gamble, rather than intentions to use a strategy to reduce gambling. Addressing this significant gap, Procter et al. (2019) investigated the use of the TPB to predict the uptake of RG tools in an Australian online betting site. This study recruited 564 gamblers (193 at follow-up) and measured the use of any of three RG tools (e.g., deposit limits, temporary self-exclusion and receiving activity statements). They reported over a 2-week period the modal number of tools used was one with 35% of gamblers not using any tools at all. Past use, attitudes (i.e., positive attitude towards tool use) and subjective norms (i.e., important others supportive of tool use) were associated with intention to use tools (but not PBC, i.e., confidence/self-efficacy of tool use), and within the sub-sample who completed follow-up, intention to use tools was correlated with actual tool use 30 days later. These promising findings indicate the TPB may further be a useful theory for understanding the correlates of a broader range of behaviour change strategies.

The current study is the first empirical study that applies the TPB to the field of behaviour change strategies gamblers use to stick to their limits or reduce their gambling. To address the limitations of previous studies, as recently highlighted by Procter et al. (2019), we included the following components: (i) a 30-day follow-up evaluation to determine whether the intended use of strategies predicted their uptake, (ii) a comprehensive list of 99 individual strategies that could be used for sticking to limits (RG and protective behavioural strategies) or reducing gambling behaviours (behaviour change strategies) and (iii) a broad community sample that included online- and land-based gamblers and included those classified as no problem (n = 79, 19%) and at least one problem as identified by the PGSI (n = 332, 81%). Understanding the TPB factors to target is important in promoting the uptake of strategies as we know that the use of these strategies is helpful to gamblers in the prevention and reduction of gambling-related harm. The aim of this study is to use the TPB to identify underlying factors associated with strategy engagement. We hypothesise that after controlling for age, gender, distress and gambling severity, (i) the TPB factors of attitude, subjective norm and PBC will predict intentions to use strategies, and (ii) intention to use strategies will predict the subsequent use of cognitive or behavioural strategies over a 30-day period.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Recruitment

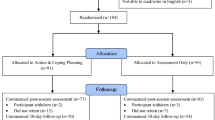

Participants were recruited between May 2014 and June 2014 as part of a larger study of strategies used by gamblers to limit or reduce their gambling behaviours (Lubman et al. 2015). A total of 1002 respondents consented to participate in the baseline survey. Of these, 23 dropped out immediately (i.e., prior to responding to any questions following acknowledgement of consent), and a further 263 dropped out prior to completing the strategies section. The final sample consisted of 716 participants. Recruitment involved free and paid advertising, and promotion across a range of websites, as well as direct contact with organisations providing gambling services (i.e., industry, treatment, government) and past gambling research participants. There were no inclusion or exclusion criteria for participation; however, study promotional materials were focused on recruiting participants who had attempted to stick to limits or reduce their gambling. For instance: ‘Gambling – Staying within your limits. Give our tips the thumbs up – which tips work for you?’ Participants who completed the baseline survey were subsequently invited to take part in a follow-up survey, which attracted 57.4% of the original sample (n = 411). The follow-up survey captured the use of change strategies in the 30 days following completion of the baseline survey. The average time between completion of surveys was 35.39 days (SD = 8.79). Ethical approval for the study was gained from Eastern Health Research and Ethics Committee (study registration number LR22/1314).

Measures

The Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) was used to measure gambling severity (Ferris and Wynne 2001). The PGSI is a 9-item scale with moderate internal consistency (α = .84), and acceptable test–retest reliability (α = .78). Scores range from 0 to 27, with 0 indicating non-problem gambler, 1–2 indicating low-risk gambler, 3–7 indicating moderate-risk gambler and 8+ indicating problem gambling.

The Kessler 6 (K6) screens for non-specific psychological distress in the past 4 weeks (Kessler et al. 2002). It contains six items related to psychological distress (e.g., nervousness, agitation, fatigue, depression). The response options range from 0 (none of the time) to 4 (all of the time) with scores of 13 or more indicating psychological distress (Kessler et al. 2003). The Cronbach’s alpha for the K6 in this study was .94.

The theory of planned behaviour scale comprised 9-items (Table 1), based on recommendations by Fishbein and Ajzen 2011. Each item targeted the use of sticking to limits over the next 30 days with two items per attitude, subjective norm and PBC. It also included two single item measures of intention, and one of behaviour (Fishbein and Ajzen (2011). Item 3 (subjective norm) was scored ‘Not at all guided’, ‘Unguided’, ‘Slightly unguided’, ‘Neither guided or unguided’, ‘Slightly guided’, ‘Guided’ and ‘Extremely guided’. All other items were scored 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 7 = ‘strongly agree’. Results from exploratory factor analysis and scale reliability indicated strong internal consistency for the multi-item subscales of attitude (rs = .91) and PBC (rs = .76), with only weak levels indicated for subjective norm (rs = .35). Consequently, the single item ‘When it comes to addressing your gambling, how much are you guided by the opinion of important people in your life?’ which loaded alone in the EFA, was used as an indicator of subjective norm. Mean scores were created for each multi-item TPB component, with higher scores indicating stronger attitudes, subjective norm and PBC towards the intended use of strategies.

The Change Strategies Questionnaire—Version-1 (Rodda et al. 2018a) contains 99 different strategies grouped into 15 categories. Factor analysis with 489 gamblers (including 333 problem gamblers) indicated the presence of 15 categories (accounting for 60.33% of the variance): cognitive, well-being, consumption control, behavioural substitution, financial management, urge management, self-monitoring, information seeking, spiritual, avoidance, social support, exclusion, planning, feedback and limit finances (Rodda et al. 2018a). Strategies are rated over a 30-day period according to their use (used/not used) resulting in a score of between 0 and 99.

Statistical Analysis Plan

Descriptives of sample demographics were conducted, followed by group comparisons (comparing those who did and those who did not complete the 30-day follow-up survey), using chi-square (categorical variables) and independent sample t tests (continuous variables). Pearson’s correlations are presented to show the univariate relationships between the TPB variables, intentions to use at least one strategy and the number of strategies used and demographics. Two linear regressions were conducted to test (i) the TPB variables of attitude, subjective norm and PBC predicting intention and (ii) intention predicting strategy use, while statistically adjusting for demographics (i.e., age, gender, gambling severity and distress). Two additional regressions were undertaken to determine if intentions was a mediator between the TPB distal factors (attitude, subjective norm, PBC) and subsequent strategies use (Martin et al. 2010) as indicated by the TPB model. Adjusted R2, a measure of explained variance, is reported to indicate effect size of each model. Significance was set at p < .05. Data analysis was undertaken with IBM SPSS Statistics (v25).

Results

Sample Characteristics and Strategy Engagement

There were no significant differences between those who completed both the baseline and 30-day follow-up survey (n = 411) and those who only completed the baseline survey (n = 305) on demographics (age, gender, marital status, PGSI, psychological distress) or TPB variables (attitude, subjective norm, PBC, intention or number of strategies intending to use). As indicated on Table 2, two-thirds of the sample were male with most aged greater than 35 years of age. One-third of the sample aimed to maintain their current gambling behaviours and 46% wanted to cut-down or stop gambling. There were also 90 (22%) participants who had a goal of maintaining their current reduction plan. Over 80% of the sample were at some level of gambling risk with almost 50% classified as problem gamblers. In addition, 19.2% (n = 79) also reported elevated levels of psychological distress. At baseline, participants indicated that they intended to implement between 0 (n = 106, 26% of sample) and 10 or more strategies (n = 1, 4% of sample). The median number of strategies subsequently used was 30 (IQR 1 = 11, IQR 3 = 56). In total, 91.5% (n = 376) of gamblers implemented at least one strategy to stick to their limits over the 30-day period.

Average scores and correlations between the TPB variables and demographics are presented in Table 3. All relationships between the TPB variables were positive, significant (p < .001) and above .4, with the exception of PBC and behaviour (r = .2). Attitude and the single-item intention measure were correlated at .93 indicating multi-collinearity. Therefore, the intention measure used in subsequent regression analyses testing the TPB relationships was ‘Over the next 30 days, how many strategies do you expect to implement?’ rather than ‘I intend to undertake at least one strategy to maintain or limit my gambling over the next 30 days’.

T test results indicated that participants in the problem gambling group scored significantly higher on all TPB model variables compared with the no problem group: total strategies used (no problem M = 22.00, SD = 23.78, problem M = 53.18, SD = 28.26; t(409) = 12.12, p < .001), intention to use strategies (no problem M = 3.72, SD = 2.06, problem M = 5.65, SD = 1.61; t(409) = 10.58, p < .0001), attitude (no problem M = 3.79, SD = 2.02, problem M = 5.67, SD = 5.47, t(409) = − 0.85, p < .001), subjective norm (no problem M = 3.06, SD = 2.77, problem M = 4.32, SD = 2.10, t(409) = 6.12, p < .001) and PBC (no problem M = 4.65, SD = 1.98, problem M = 5.56, SD = 1.47, t(409) = 5.27, p < .001).

Testing the TPB Model

All variables in the proposed models to be tested were correlated and subsequently included in regressions. Regressions to test the TPB model pathways are presented in Table 4 with regressions testing mediation in Table 5. The model of predicting intentions to use at least one strategy was significant (model 1: F(7, 390) = 40.95, p < .001). Along with gender and gambling severity (PGSI), TPB factors of attitude and PBC were significant predictors of intention (but not subjective norm). The model of predicting strategy use was significant (model 2: F(5, 392) = 32.52, p < .001). Along with gambling severity (PGSI) and distress, intention to use a strategy was a significant predictor of subsequent use of strategies (see Table 4).

Examining intention as a mediator, regression model 3 (predicting strategies with TPB factors excluding intention: Model 3: F(7, 390) = 19.85, p < .001) and regression model 4 (predicting strategies with TPB factors including intention: Model 4: F(8,389) = 21.04, p < .001) were both significant. Attitude was a significant predictor in model 3, but once intention was included in model 4, attitude was no longer significant and intention was a significant predictor of strategy use. This change indicates that the influence of attitude on strategy engagement was mediated through intention (i.e., attitude no longer directly influenced strategy engagement, but indirectly influenced use by impacting intentions). PGSI was a consistent significant predictor in all regressions (i.e., predicted intention to use strategies, predicted number of strategies used).

Discussion

This prospective study aimed to understand factors associated with the uptake of a broad range of strategies for limiting or reducing gambling behaviours. Applying the theoretical framework of the TPB, it is the first study to systematically explore the role of attitudes, subjective norms and PBC on intention to use strategies with a large sample of gamblers recruited from a community setting. As hypothesised, attitude and PBC predicted intention to use strategies after controlling for age, gender, distress and gambling severity. Contrary to expected, subjective norm was not significantly associated with intention. The second hypothesis was supported: the intention to use strategies prospectively predicted actual strategy engagement over a 30-day period.

The application of the TPB to examine predictors of strategy engagement to limit or reduce gambling is a relatively new endeavour in the gambling field. Just one study has sought to understand the reasons for strategy engagement (Procter et al. 2019). The aim of the Proctor and colleagues' study was to predict the use of three RG tools (i.e., activity statement, deposit limits and temporary exclusion). They reported two of three TPB factors were associated with intention to use a tool (i.e., attitudes and subjective norm). The authors concluded PBC was not a factor in tool engagement because the three tools were not effortful and were relatively easy to use (thereby negating the need for PBC). In contrast, our results revealed PBC was important. We examined engagement with 99 different strategies whereby the effort required for each strategy ranged from a little effort to a large effort (and level of difficulty ranging from easy to hard). For example, some strategies required low effort and were likely not difficult to implement (e.g., Remind yourself of negative consequences of gambling), whereas others were not difficult to implement but required greater effort and self-control (e.g., Postpone gambling until a later date). Other strategies may have been both difficult to implement and effortful because they required the acquisition of new skills or resources, as well as the gambler being able to overcome barriers such as shame and embarrassment that may be associated with the action when other people were involved (e.g., Consolidate debts and implement payment plan; disclose to someone else the extent of your gambling). Rodda et al. (2018a) found strategies such as seeking feedback (e.g., calculating how much money has been spent on gambling) or planning (e.g., plan ahead and leave cards and cash at home) are reported by gamblers as more helpful than simplistic strategies (e.g., Remain hopeful about your future). Conversely, the same study reported strategies that require effort such as exclusions or self-monitoring were rated as only a little helpful (Rodda et al. 2018a). In the current study, gamblers reported high agreement that they were in control of the types of strategies they could implement, and it may be that the types of strategies selected meet their needs in terms of the desired amount of effort or difficulty (rather than what is most helpful). Future research should further examine the impact the degree of perceived effort and difficulty has on the selection of strategies. This detail would assist industry and governments to identify where support could be provided to gamblers for those strategies that are likely helpful but require effort or new skills and knowledge to implement.

Contrary to our hypothesis, subjective norm did not predict intention to use a strategy to limit or reduce gambling behaviour. Another study involving adolescent gamblers also reported subjective norm as being the weakest variable in predicting gambling intentions (St-Pierre et al. 2015). When gambling becomes a problem, a range of harms are reported by family and friends (Kalischuk et al. 2006). There have been multiple studies reporting family members ask the gambler to change their behaviour (Kourgiantakis and Ashcroft 2018) and others that have reported this approach as helpful in reducing problem gambling (Kourgiantakis et al. 2018). In contrast, there are very few studies that focus on the mechanisms of change and how family members may influence strategy engagement. To date, a small number of studies have established that family members seek advice from support services on how to support gamblers’ behaviour change over the longer term (Hing et al. 2013; Riley et al. 2018; Rodda et al. 2019b). Future research might consider how family members can better support gamblers in the implementation of strategies for gambling reduction and how they might let the gambler know that the implementation of these strategies is important. This approach may be especially important when the intended strategy is effective, but complex or difficult and effortful to implement (e.g., debt consolidation, self-exclusion).

This study found targeting attitudes directly towards strategy use will have its limitations. Instead, it may be more effective to target attitudes towards wanting or intending to use strategies. RG programmes target a sub-set of strategies aimed at sticking to limits in venues (e.g., set a limit) as well as minimising gambling-related harm (e.g., avoid chasing losses). For example, a study by Hing et al. (2017) reported a selection of RG messages promoted in Australia. The messages reported in this study were frequently instructional (e.g., keep gambling in balance with other activities), negative (e.g., it advises people to be aware they will likely lose) and fear-inducing (e.g., it warns of the risks of gambling). In addition, multiple studies have reported that gamblers have positive attitudes towards the use of strategies to limit or reduce their gambling (Nower and Blaszczynski 2010; Procter et al. 2019). The current study suggests RG messaging might be more effective if it influences attitudes and PBC to improve intentions to use strategies (model 1, 41% of variance) as intentions subsequently influence behaviour (model 2, 29% of the variance). This means shifting messaging away from behaviour and towards these factors that influence intention. As suggested by Procter et al. (2019), promotion of these positive attitudes towards RG tools could assist in normalising their engagement as a way of sticking to limits.

Our second aim was to predict the subsequent use of change strategies over a 30-day period. Our study found intentions were a significant predictor of behaviour and this explained almost 30% of the variance. This is the first time any study has attempted to predict engagement with a broad range of strategies and these findings indicate that if we are able to influence gamblers’ intentions, then they will likely implement a strategy to limit or reduce their gambling. We also found gambling severity as measured by the PGSI was a consistent significant predictor in all regressions whereby it predicted intention to use strategies as well as the number of strategies used. While our study indicated that all gamblers use strategies to limit or reduce their gambling (not just people with gambling problems), the number of strategies implemented increased with the level of gambling severity. This result is consistent with other studies which have also reported a positive correlation between strategy use and gambling severity (Moore et al. 2012; Rodda et al. 2018a). The current study suggests that as gambling becomes more problematic, there is an intention to implement more strategies. This finding is perhaps counter-intuitive; whereby at a certain point, the use of more strategies is related to less success as indicated by lapse and relapse. It may be that choosing the right strategy at the right time is more important than the number of strategies. Future research may consider alternative methods to identify strategy engagement and correlates such as those in the TPB. For example, ecological momentary assessment (Shiffman 2009) permits the collection of real-time data and could further illuminate influential factors that may further explain the established gap in the relationship between intention and behaviour.

Study Limitations

This study is the first to apply the TPB to strategy engagement for limiting or reducing gambling, but it is not without its limitations. First, this study relied on self-report of a large number of strategies and this potentially affected the reliability and validity of the data. Second, to minimise participant burden, two items were used for each of the TPB variables. We adapted TPB questions for engagement with strategies to limit or reduce gambling behaviours. While these were based on previous research and item development recommendations (Fishbein and Ajzen 2011), factor analysis indicated the two subjective norm items were measuring different constructs. As such, only one subjective norm item was represented in the final analysis. The difficulty of adapting TPB is highlighted in the only other study on strategy engagement and the TPB (i.e., Procter et al. 2019), which, similar to our subjective norm item, reported low internal consistency of PBC (which may in part explain why it did not perform as expected). To address this issue, future research should develop a more robust measure for TPB and strategy engagement that is appropriate for any study investigating strategy engagement whether that be in the field of RG, protective behavioural strategies and/or behaviour change strategies.

Third, an unexpected and important result was the large number of strategies that were implemented (median of 30). At baseline, participants were asked to nominate the number of strategies that they intended to implement over the coming 30 days. At the time of the survey development, the best available evidence indicated the average number of strategies implemented by gamblers was between two and eight (Hing et al. 2011; Moore et al. 2012) and so the intention item was capped at 10 strategies (4% of participants indicated an intention to use 10 items over the next 30 days). Future research should consider removing the cap on the number of intended strategies or ensure that it is representative of the number of strategies being tested. For example, the reason that previous research had reported less than 10 strategies were used was that these studies only included a relatively small number of items in their checklist (between 11 and 20).

The most serious limitation is the absence of evidence indicating for whom and when these strategies are effective. To our knowledge, there have been no studies examining the relationship between the use of strategies and the impact on gambling time or money spent or gambling severity. Some studies have examined self-reported helpfulness (Hing et al. 2011; Rodda et al. 2018a), but whether these strategies are impactful on actual gambling behaviour remains unknown. The expansion of online gambling provides new opportunities to track the impact of strategies on time and money spent on gambling (Procter et al. 2019).

Clinical Implications

Gamblers hold positive attitudes towards the use of strategies to limit or reduce their gambling and this should be supported. It is generally recommended that anyone with a gambling problem should seek face-to-face treatment. Typically delivered as CBT or motivational interviewing, face-to-face treatment is effective in reducing gambling problems and it can have a long-term and lasting impact (Cowlishaw et al. 2012). Despite this promise, most people with gambling problems do not access face-to-face treatment. The reasons for not seeking treatment are reported as minimising the extent of the problem (frequently reported in the literature as ‘denial’) and wanting to self-manage as well as a vast range of other barriers including stigma, access, cost and perceptions of helpfulness (Evans and Delfabbro 2005; Gainsbury et al. 2014; Suurvali et al. 2009). Conversely, gamblers demonstrate strong positive attitudes towards the use of strategies to limit or reduce their gambling and most gamblers do actually use their intended strategies. Future research should build on these positive attitudes and extend the scope of treatment services to support gamblers in the successful implementation of their strategies. Based on the current findings, this content should include skills development for complex strategies that are difficult to implement as well as motivational support for those that are effortful.

The current study demonstrates the utility of the TPB to understand some of the factors associated with strategy engagement, but it does not explain why gamblers develop problems despite their use of cognitive and behavioural strategies. The current study found we can explain a large amount of variance in intentions to use strategies (about 40%), which in turn, predicted a smaller amount of subsequent strategy use (i.e., behaviour; 28%). This finding is consistent with the broader TPB literature which reports intention typically accounts for 20 to 30% or the variance in future behaviour (Sheppard et al. 1988). This intention-behaviour gap is reported across multiple target behaviours (Sniehotta et al. 2014; Sniehotta et al. 2005) and indicates that some people fail to take action despite having a positive attitude and self-efficacy towards taking such action (Sheeran 2002). Reasons for the gap identified here may be attributable to initial strategy selection and/or subsequent implementation practices. For example, gamblers may underestimate the difficulty or effort required for the action, there may be a lack of planning or access to resources, or they may forget to act when other activities become more salient. Therefore, both strategy selection and subsequent implementation practices may be relevant to minimise the intention-behaviour gap. In terms of strategy selection, Rodda et al. (2017) examined the transcripts of 149 gamblers accessing treatment and found gamblers were poor in selecting the right strategy for their specific need, had poor or unplanned transitions between strategies and selected strategies that were competing and prematurely abandoned strategies without review or evaluation. Action planning can be used to support strategy selection and implementation (i.e., strategy components of what, how, who, when) (Sniehotta et al. 2005). In addition, coping planning (also referred to as implementation intentions) assists individuals to pre-empt likely barriers to implementation and develop ‘if..then...’ plans (Sniehotta et al. 2005). Just one study has been conducted investigating strategy selection and implementation supported with the use of tailored action and coping planning with gamblers, with positive results (Rodda et al. 2019a). Although both groups in the RCT intended to spend median $200 over the next 30 days, problem gamblers receiving the brief intervention gambled almost half as much money (median $290) compared with the control group (median $500). Thus, supporting the translation of gamblers’ strategy implementation intentions into behaviours is feasible and warrants further investigation.

The current study is the first to systematically look at factors associated with strategy engagement, specifically with the intention to use, and subsequent use of strategies, to limit or reduce gambling behaviours. It has several strengths including the recruitment of a large sample of gamblers from a community setting, the inclusion of gambling severity, the examination of a wide range of strategies and the measurement of actual behaviour. Together with Procter et al. (2019), our studies are important in establishing a new stream of research which shifts the focus solely from gambling outcomes and instead towards understanding the mechanisms underlying strategy engagement.

The findings indicate that intention to use a strategy is related to attitude and PBC (but not subjective norms) and that intention is a strong predictor of actual use. These findings are broadly consistent with previous research but highlight the importance of further understanding the perceived and actual role of family members. For instance, it would be useful to know the extent to which family members are aware or supportive of the mechanisms of behaviour change. This study also suggests that the most parsimonious solution to the low uptake of gambling treatment systems is to shift the focus of treatment systems towards the gambler rather than trying to shift the gambler into treatment. The current study indicates gamblers hold positive attitudes towards strategies designed to limit or reduce their gambling and believe that they are able to implement these strategies. To better support gamblers in implementation of these strategies, there is now urgent need for theory-driven empirical evidence to guide intervention development. This approach is especially important as beyond the uptake of strategies, there are no known treatments that are broadly acceptable to people with any level of gambling problem. As low- and moderate-risk gamblers shoulder the burden of most of the gambling-related harm, interventions that support strategy engagement for them are urgently needed.

References

Abbott, M., Bellringer, M., Garrett, N., & Mundy-McPherson, S. (2014). New Zealand 2012 national gambling study: Gambling harm and problem gambling. New Zealand: Auckland University of Technology.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(4), 471–499.

Armstrong, A., & Carroll, M. (2017). Gambling activity in Australia. Melbourne. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Blaszczynski, A., Collins, P., Fong, D., Ladouceur, R., Nower, L., Shaffer, H. J., Tavares, H., & Venisse, J.-L. (2011). Responsible gambling: General principles and minimal requirements. Journal of Gambling Studies, 27(4), 565–573.

Browne, M., Langham, E., Rawat, V., Greer, N., Li, E., Rose, J., et al. (2016). Assessing gambling-related harm in Victoria: A public health perspective. Melbourne: Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation.

Conner, M., McEachan, R., Taylor, N., O'hara, J., & Lawton, R. (2015). Role of affective attitudes and anticipated affective reactions in predicting health behaviors. Health Psychology, 34(6), 642–652.

Cooke, R., Dahdah, M., Norman, P., & French, D. P. (2016). How well does the theory of planned behaviour predict alcohol consumption? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 10(2), 148–167.

Cowlishaw, S., Merkouris, S., Dowling, N., Anderson, C., Jackson, A., & Thomas, S. (2012). Psychological therapies for pathological and problem gambling. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 11, CD008937. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008937.pub2.

Cowlishaw, S., Merkouris, S., Dowling, N., Rodda, S. N., Suomi, A., & Thomas, S. (2018). Locating gambling problems across a continuum of severity: Rasch analysis of the Quinte Longitudinal Study (QLS). Addictive Behaviors, 92, 32-37. doi:org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.12.016.

Dahl, E., Tagler, M. J., & Hohman, Z. P. (2018). Gambling and the reasoned action model: Predicting past behavior, intentions, and future behavior. Journal of Gambling Studies, 34(1), 101–118.

Evans, L., & Delfabbro, P. H. (2005). Motivators for change and barriers to help-seeking in Australian problem gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies, 21(2), 133–155.

Ferris, J. A., & Wynne, H. J. (2001). The Canadian problem gambling index: User manual. Toronto, ON: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2011). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. New York: Psychology Press.

Flack, M., & Morris, M. (2017). The temporal relationship between gambling related beliefs and gambling behaviour: A prospective study using the theory of planned behaviour. International Gambling Studies, 17(3), 508–519.

Forsström, D., Jansson-Fröjmark, M., Hesser, H., & Carlbring, P. J. I. (2017). Experiences of Playscan: Interviews with users of a responsible gambling tool. Internet Interventions 8, 53–62.

Gainsbury, S., Hing, N., & Suhonen, N. (2014). Professional help-seeking for gambling problems: Awareness, barriers and motivators for treatment. Journal of Gambling Studies, 30(2), 503–519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-013-9373-x.

Godin, G., & Kok, G. (1996). The theory of planned behavior: A review of its applications to health-related behaviors. American Journal of Health Promotion, 11(2), 87–98.

Hing, N., Nuske, E., & Gainsbury, S. (2011). Gamblers at-risk and their help-seeking behaviour. Melbourne: Gambling Research Australlia.

Hing, N., Tiyce, M., Holdsworth, L., & Nuske, E. (2013). All in the family: Help-seeking by significant others of problem gamblers. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 11(3), 1–13.

Hing, N., Sproston, K., Tran, K., & Russell, A. M. (2017). Gambling responsibly: Who does it and to what end? Journal of Gambling Studies, 33(1), 149–165.

Hodgins, D. C., & el-Guebaly, N. (2000). Natural and treatment-assisted recovery from gambling problems: A comparison of resolved and active gamblers. Addiction, 95(5), 777–789.

Kalischuk, R. G., Nowatzki, N., Cardwell, K., Klein, K., & Solowoniuk, J. (2006). Problem gambling and its impact on families: A literature review. International Gambling Studies, 6(1), 31–60.

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S.-L., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976.

Kessler, R. C., Barker, P. R., Colpe, L. J., Epstein, J. F., Gfroerer, J. C., Hiripi, E., et al. (2003). Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(2), 184–189.

Kim, H. S., Wohl, M. J., Salmon, M., & Santesso, D. (2017). When do gamblers help themselves? Self-discontinuity increases self-directed change over time. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 148–153.

Kourgiantakis, T., & Ashcroft, R. (2018). Family-focused practices in addictions: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open, 8(1), e019433.

Kourgiantakis, T., Saint-Jacques, M.-C., & Tremblay, J. (2018). Facilitators and barriers to family involvement in problem gambling treatment. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 16(2), 291–312.

Ladouceur, R., Shaffer, P., Blaszczynski, A., & Shaffer, H. J. (2017). Responsible gambling: A synthesis of the empirical evidence. Addiction Research & Theory, 25(3), 225–235.

Langham, E., Thorne, H., Browne, M., Donaldson, P., Rose, J., & Rockloff, M. (2016). Understanding gambling related harm: A proposed definition, conceptual framework, and taxonomy of harms. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 80.

Lostutter, T. W., Lewis, M. A., Cronce, J. M., Neighbors, C., & Larimer, M. E. (2014). The use of protective behaviors in relation to gambling among college students. Journal of Gambling Studies, 30(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-012-9343-8.

Lubman, D. I., Rodda, S. N., Hing, N., Cheetham, A., Cartmill, T., Nuske, E., et al. (2015). Gambler self-help strategies: A comprehensive assessment of self-help strategies and actions. Melbourne: Gambling Research Australia.

Martin, R. J., Usdan, S., Nelson, S., Umstattd, M. R., LaPlante, D., Perko, M., & Shaffer, H. (2010). Using the theory of planned behavior to predict gambling behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(1), 89–97.

Matheson, F. I., Hamilton-Wright, S., Kryszajtys, D. T., Wiese, J. L., Cadel, L., Ziegler, C., Hwang, S. W., & Guilcher, S. J. (2019). The use of self-management strategies for problem gambling: A scoping review. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 445.

Moore, S. M., & Ohtsuka, K. (1999). The prediction of gambling behavior and problem gambling from attitudes and perceived norms. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 27(5), 455–466.

Moore, S. M., Thomas, A. C., Kyrios, M., & Bates, G. (2012). The self-regulation of gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 28(3), 405–420.

Nower, L., & Blaszczynski, A. (2010). Gambling motivations, money-limiting strategies, and precommitment preferences of problem versus non-problem gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies, 26(3), 361–372.

Procter, L., Angus, D. J., Blaszczynski, A., & Gainsbury, S. M. (2019). Understanding use of consumer protection tools among internet gambling customers: Utility of the Theory of Planned Behavior and Theory of Reasoned Action. Addictive Behaviors, 99, 106050.

Riley, B. J., Harvey, P., Crisp, B. R., Battersby, M., & Lawn, S. (2018). Gambling-related harm as reported by concerned significant others: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of empirical studies. Journal of Family Studies, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1322940.2018.1513856

Rodda, S. N., Hing, N., Hodgins, D. C., Cheetham, A., Dickins, M., & Lubman, D. I. (2017). Change strategies and associated implementation challenges: An analysis of online counselling sessions. Journal of Gambling Studies, 33(3), 955–973. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-016-9661-3.

Rodda, S. N., Bagot, K. L., Cheetham, A., Hodgins, D. C., Hing, N., & Lubman, D. I. (2018a). Types of change strategies for limiting or reducing gambling behaviors and their perceived helpfulness: A factor analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 32(6), 679–688. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000393.

Rodda, S. N., Dowling, N., & Lubman, D. (2018b). Gamblers seeking online help are active help-seekers: Time to support autonomy and competence. Addictive Behaviors, 87, 272–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.06.001.

Rodda, S. N., Hing, N., Hodgins, D. C., Cheetham, A., Dickins, M., & Lubman, D. I. (2018c). Behaviour change strategies for problem gambling: An analysis of online posts. International Gambling Studies, 18(3), 420–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2018.1432670.

Rodda, S. N., Bagot, K. L., Manning, V., & Lubman, D. I. (2019a). Only take the money you want to lose’ strategies for sticking to limits in electronic gaming machine venues. International Gambling Studies, 19(3), 489–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2019.1617330

Rodda, S. N., Dowling, N. A., Thomas, A. C., Bagot, K., Knaebe, B., & Lubman, D. I. (2019b). “He doesn’t see it as a big problem, I need to seek help”: What do family members of gamblers want and expect from online counselling? International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00143-9

Salonen, A. H., Castrén, S., Raisamo, S., Orford, J., Alho, H., & Lahti, T. (2014). Attitudes towards gambling in Finland: A cross-sectional population study. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 982.

Sheeran, P. (2002). Intention—behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. European Review of Social Psychology, 12(1), 1–36.

Sheppard, B. H., Hartwick, J., & Warshaw, P. R. (1988). The theory of reasoned action: A meta-analysis of past research with recommendations for modifications and future research. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(3), 325–343.

Shiffman, S. (2009). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychological Assessment, 21(4), 486–497.

Sniehotta, F. F., Schwarzer, R., Scholz, U., & Schüz, B. (2005). Action planning and coping planning for long-term lifestyle change: Theory and assessment. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35(4), 565–576.

Sniehotta, F. F., Presseau, J., & Araújo-Soares, V. (2014). Time to retire the theory of planned behaviour. Health Psychology Review, 8(1), 1–7.

St-Pierre, R. A., Derevensky, J. L., Temcheff, C. E., & Gupta, R. (2015). Adolescent gambling and problem gambling: Examination of an extended theory of planned behaviour. International Gambling Studies, 15(3), 506–525.

Suurvali, H., Cordingley, J., Hodgins, D. C., & Cunningham, J. (2009). Barriers to seeking help for gambling problems: A review of the empirical literature. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25(3), 407–424.

Williams, R. J., Volberg, R. A., & Stevens, R. M. (2012). The population prevalence of problem gambling: Methodological influences, standardized rates, jurisdictional differences, and worldwide trends. Report prepared for the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. http://hdl.handle.net/10133/3068. Accessed 8 May 2012

Wu, A. M., & Tang, C. S.-K. (2012). Problem gambling of Chinese college students: Application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Gambling Studies, 28(2), 315–324.

Funding

This work was supported by Gambling Research Australia (GRA). GRA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript or the decision to submit the paper for publication. The University of Auckland (Faculty of Medical Health Sciences) provided support for the preparation of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors Kathleen L Bagot, Dan I. Lubman and Simone N Rodda designed the study and wrote the protocol. Author Kathleen L Bagot conducted the data analysis. Authors Kathleen L Bagot and Simone N Rodda wrote the first drafts of the manuscript and all authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to this article. Over the past 3 years, all authors have received funding from multiple sources, including government departments or agencies that are funded primarily by government departments (some through hypothecated taxes from gambling revenue). SR has been part of a small research grant from the National Association for Gambling Studies. None of the authors have knowingly received research funding from the gambling industry or any industry-sponsored organisation.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bagot, K.L., Cheetham, A., Lubman, D.I. et al. Predictors of Strategy Engagement for the Prevention and Reduction of Gambling Harm: a Prospective Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Int J Ment Health Addiction 19, 1812–1828 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00265-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00265-5