Abstract

This study examined the mediating effects of job satisfaction and life satisfaction on the relationship between work–family conflict and depression in professional women. A total of 443 professional women completed questionnaires that measured work–family conflict, job satisfaction, life satisfaction, and depression. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was adopted to test the mediating effect. Bootstrap methods were used to assess the magnitude of the direct and indirect effects. SEM showed that job and life satisfaction partially mediated the relationship between work–family conflict and depression. The results of the bootstrap estimation procedure and subsequent analyses indicated that the indirect effects of job and life satisfaction on the relationship between work–family conflict and depression were also significant. The final model shows a significant relationship between work–family conflict and depression through job and life satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The traditional family pattern in East Asian countries is that husbands work outside the home, whereas their wives take care of their children and perform household chores (Qian et al. 2002). However, fundamental changes in this situation have occurred in China (Schneider 2013). A study showed that nearly 350 million urban and rural women are employed in China, accounting for 44.8% of all the employees (Sznajder et al. 2014). Several surveys indicated that professional women have different degrees of psychological problems, such as anxiety, depression, and interpersonal sensitivity (Gierc et al. 2014; Melchior et al. 2007; Plaisier et al. 2007; Watson and Weinstein 1993). On the one hand, society expects women to be actively involved in social work and contribute to society; on the other hand, society does not forget the expectation of family roles they should play in Chinese culture (Gierc et al. 2014). Women juggle multiple roles, and work–family conflict ensues when the demands of functioning in these roles are incompatible in some respect. Research shows that 43% of professional women experience work–family conflict at least some of the time. Numerous studies identify work–family conflict as an important reason for the various psychological problems of professional women (Koyuncu et al. 2012; Stoner et al. 2011). This study extends this line of studies by examining whether the link between work-family conflict and depression is mediated by life and job satisfaction in Chinese professional women. And the purpose of the current study was to test whether satisfactions can protect for professional women with work-family conflict from depression.

Theoretical Background of this Study

Work–family conflict refers to a role interaction conflict, which is caused when the stress from both work and family produces irreconcilable contradictions (Ádám et al. 2008; Amstad et al. 2011; Peng et al. 2016). In other words, individuals have difficulty taking responsibility for their families due to work tasks or work demands, or work tasks are not completed because of heavy family burden. Greenhaus and Beutell further distinguished work–family conflict; that is, conflict caused by job demands pertains to work-to-family conflict, whereas conflict caused by family demands connotes family-to-work conflict (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985). Studies indicated an overlap between work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict (Frone et al. 1997b). People often experience higher work-to-family conflict than family-to-work conflict (Mesmer-Magnus and Viswesvaran 2005).

Investigations have demonstrated that outcomes associated with work–family conflict include job dissatisfaction, low commitment, job burnout, life dissatisfaction, marital dissatisfaction, and depression. Work–family conflict is a potential source of stress that has negative effects on well-being and behavior (Xiao et al. 2014). Warr’s argument postulates the direct effects of stress on related well-being and indirect effects on more general indicators of strain; conflict between family and work is causing problems in well-being and further effects on health or mental health problem. Warr’s hypothesis is supported by empirical evidence. For example, Bedeian and his colleagues found by studying police officer samples that high-level work–family conflict was related to job burnout, alienation, and low job satisfaction (Schieman and Glavin 2011). Similarly, Frone revealed that work–family conflict was significantly related to burnout and low job satisfaction (Frone 2000). Kalliath and Kalliath recently reported that work–family conflict was negatively correlated with job satisfaction and positively correlated with depression and physical discomfort in a group of social workers (Kalliath and Kalliath 2013). Moreover, work–family conflict could influence life-related variables. For example, Higgins and his colleagues found that work–family conflict was related to low family life quality, and low family life quality was also related to low life satisfaction (Higgins et al. 1992). Another study showed that work–family conflict was negatively correlated with job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and life satisfaction (Rupert et al. 2012).

Mediating Role of Job and Life Satisfaction

Studies within the paradigms of job demands–resources model and role theory have confirmed the hypothesis that work–family conflict is negatively related to the indicators of subjective well-being, such as job and life satisfaction. On the contrary, researchers have proved that an imbalance between efforts spent and rewards induces effort–reward imbalance. This situation produces work–family conflict-related stress and accumulates over time as a function of the sum of current and past exposures creates strain. Stress reaction models have indicated that the results of conflict-related stress are associated with depression and depression symptoms. Under the role–stress perspective, pathways from work–family conflict stress to the development of depression or depression symptom are highly relevant. Studies have established a strong association between stress-related well-being and work–family conflict. Well-being is also the most popular indicator studied. Moreover, well-being is related to several indicators of mental health, such as depression. These findings reveal a trend that life satisfaction and job satisfaction play a mediating role between work–family conflict and depression. Life and work are two important aspects of the lives of professional women, and work–family conflict has an important influence on both aspects. Life satisfaction and job satisfaction are the best indicators that people experience life and work environment (Diener et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2014b). However, no study has specifically investigated life and job satisfaction as mediating variables of work–family conflict and depression. The current study aimed to discuss the effect of work–family conflict on the depression of professional women and explore the mediating effects of life satisfaction and job satisfaction between work-family conflict and depression.

Hypotheses of this Study

A large number of studies have shown that work–family conflict can influence people’s mental health, particularly professional women’s depression (Allen et al. 2000; Grzywacz and Bass 2003; Schieman and Glavin 2011). However, the psychological mechanism underlying the effect of work–family conflict on depression is seldom discussed. The present study aimed to fill this void. Based on the opinion of source attribution model, an individual will be dissatisfied with the role that is perceived to be the source of the conflict. This study hypothesized that work–family conflict as a stressor will reduce professional women’s well-being, such as life and job satisfaction. Furthermore, those who are dissatisfied with their lives are more likely to withdraw from others, consequently inducing depression. Given the close relationship between job or life satisfaction and depression, these professional women are expected to be more likely to suffer from depression. Another hypothesis is that that individuals with high work–family conflict may suffer from depression because of low job and life satisfaction.

In summary, the study hypothesized that life and job satisfaction mediated the effect of work–family conflict on depression. This study seeks to enhance the understanding of the relationships among work–family conflict, life and job satisfaction, and depression among Chinese professional women. It also aims to supplement previous research by addressing the concurrent effects of the preceding variables on depression. This study may help in the development of prevention and treatment programs that focus on well-being as an effective response to stress induced by work–family conflict.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

A total of 443 female staff members from three large-scale enterprises in China were selected as participants. The ages of the participants ranged from 30 to 39, with a mean of 33.12 (SD = 2.14) and had at least one child dependent on them. These are all full-time employees in China without exception of freelancers, self-employees and civil servants. All of the participants are married, with average 9.3 years (SD = 2.38) of work experience. 255(57.56%) of the participants had obtained a diploma or higher level educational qualification; 137(30.93%) had completed high school while 51(11.51%) had not completed high school. The participants were told that they were engaging in a psychological investigation, in which the items accepted no correct or incorrect answers, and their names can be omitted from the questionnaires. Participants completed the questionnaires in a classroom environment with a face-to-face, pencil and paper format, and they received ¥20 as compensation for their participation. All participants obtained informed consent before completing the measures. The 443 scales were distributed and collected, and all of them were valid. Thus, 443 valid responses were used for data analysis.

Instruments

Work–Family Conflict

The work–family conflict scale, which was developed by Carlson, Kacmar, and Williams, was employed to measure work–family conflict and family–work conflict (Carlson et al. 2000). This scale consists of two subscales, namely, work-to-family conflict scale and family-to-work conflict scale. Each subscale consists of nine items. An example item is “When I get home from work, I am often too frazzled to participate in family activities/responsibilities.” Responses were made on a five-point Likert-type scale. The work-to-family conflict scale measures the work-to-family direction of conflict. An example item is “When I get home from work, I am often too frazzled to participate in family activities/responsibilities.” The family-to-work conflict scale measures the family-to-work direction of conflict. An example item is “Tension and anxiety from my family life often weaken my ability to do my job.” Chinese scholars translated the scale into Chinese and tested the reliability and validity (Wang et al. 2012). In the current study, the Cronbach alpha coefficients for the two subscales were 0.79 and 0.75 respectively.

Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction was measured with five items (e.g., “I am satisfied with my life” and “So far, I have obtained the important things I want in life”) using a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (“definitely false”) to 7 (“definitely true”). The items were translated from the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985). In the present study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient of the life satisfaction scale was 0.81.

Job Satisfaction

The Minnesota satisfaction questionnaire (short form, MSQ) is a 20-item self-report measure of job satisfaction, which includes two dimensions, namely, intrinsic and extrinsic satisfaction (Gillet and Schwab 1975). Items are rated from 1 (“strong dissatisfaction”) to 5 (“strong satisfaction”). The total scores range from 20 (low level of job satisfaction) to 100 (high level of job satisfaction). An example of the items includes “the chance to try out some of my own ideas.” This scale has been widely used in China and shows good validity and reliability (Ouyang et al. 2015). In the present study, the Cronbach alpha coefficients of the two dimensions of MSQ were 0.84 and 0.86 respectively.

Depression

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) is a 20-item self-report measure designed to assess depressive symptoms in the general population (Radloff 1977). For each item, participants are asked to indicate how often they experienced the particular symptom over the last week. Each response ranges from 1 (“rarely or none of the time”) to 4 (“most or all of the time”). This scale has been translated in Chinese and shows good validity and reliability (He et al. 2014; Kong et al. 2014). The scores on the CES-D range from 20 to 80. High scores indicate high levels of depressive symptoms. In the present study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient of CES-D was 0.86.

Statistical Analyses

The mediating effects for life satisfaction and job satisfaction were tested using the two-step structural equation analysis procedure recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (Anderson and Gerbing 1988). First, the measurement model was tested to assess the extent to which each latent variable was represented by its indicators. Structural equation modeling (SEM) with the maximum likelihood estimation in the AMOS 17.0 program was used if the measurement model was accepted. The goodness-of-fit of the model was evaluated using the following indices: chi-square statistics; root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), which is best if below 0.06; standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR), which is best if below 0.08; and comparative fit index (CFI), which is best if above 0.95 (Anderson and Gerbing 1988; Hu and Bentler 1999; Peng et al. 2013). Finally, the bootstrap method was adopted to assess the magnitude of the direct and indirect effects. MacKinnon et al. (2004) have suggested that the bootstrap method yields the most accurate confidence intervals (CIs) for indirect effects. They have recommended the use of the percentile bootstrap, which provides a CI, reasonable control of Type 1 errors, and good statistical power.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations of all of the study variables. The results indicated that work–family conflict, life satisfaction, job satisfaction, and depression were significantly correlated with each other.

Measurement Model

The evaluation of the adequate suitability of the measurement model to the sample data required performing a confirmatory factor analysis. Five latent constructs (i.e., work-to-family conflict, family-to-work conflict, life satisfaction, job satisfaction, and depression) and 63 observed variables (all of the items for the latent variables) were included in the measurement model. All of the indices of the measurement model were suitable to the data (χ 2/df = 1.83, RMSEA = 0.058, SRMR = 0.043, and CFI = 0.96). All of the factor loadings for the indicators on the latent variables were significant (p < 0.001), which indicated a high representation of the latent constructs by their indicators. Moreover, all of the latent constructs were significantly correlated in a conceptually expected manner (p < 0.001).

Structural Model

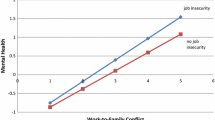

The structural model was tested in subsequent analyses using the maximum likelihood estimation in the sample of professional women. The direct path coefficient from the predictor (i.e., work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict) to the criterion (i.e., depression) in the absence of mediators was significant (β = 0.48, β = 0.32, p < 0.001). A completely mediated model with two mediators (i.e., job satisfaction and life satisfaction) revealed a good fit to the data (χ 2/df = 1.19, RMSEA = 0.021, SRMR = 0.023, and CFI = 0.99). Finally, the partially mediated model, which included the mediator (i.e., life and job satisfaction) and direct paths, was tested. The results also indicated that the model exhibited a good fit for the data (χ 2/df = 1.09, RMSEA = 0.018, SRMR = 0.019, and CFI = 0.99). However, the direct path from family-to-work conflict to depression (β = 0.08) was not significant. Thus, the path should be deleted in the current model. The final model without the direct path from family-to-work conflict to depression was tested subsequently, which revealed a good fit to the data (χ 2/df = 1.14, RMSEA = 0.019, SRMR = 0.020, and CFI = 0.99). All of the factor loadings for the indicators on the latent variables were significant (p < 0.01). The chi-square difference test showed no significance between the partially mediated model and the fully mediated model [χ 2 (1, N = 443) = 1.32, (p = n.s.)] (see Table 2). Therefore, the final partially mediated model was selected as the best representation of the data. All of the structural paths for the final model are presented in Fig. 1.

Mediating Effect Testing

The bootstrap estimation procedure in AMOS 17.0 was used to test the significance of the mediating effects of life satisfaction and job satisfaction. The basic principle for the bootstrapping approach is that the standard error estimates and CIs, which are calculated based on the assumption of a normal distribution, will usually be imprecise because the indirect effect estimates generally do not follow a normal distribution (MacKinnon et al. 2004). A bootstrap sample of 1500 tested the mediating effect. The 95% CIs of the direct and indirect effects are shown in Table 3; all the intervals did not overlap with zero. Thus, life satisfaction and job satisfaction partially mediated the effect of work–family conflict and depression.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore a model including life satisfaction and job satisfaction as mediators in the relationship between work–family conflict and depression in Chinese professional women. SEM analysis was conducted to determine the direct and indirect effect of work-to-family conflict on depression. The results indicated a good fit to the data. The study showed that, as expected, a positive relationship existed between work-to-family conflict and depression for professional women. In other words, professional women with higher levels of work-to family conflict were more likely to have higher levels of depression.

As China stepped into a rapid development period, Chinese women have to work outside the home, the issue of mental health for professional women becomes highly intense. The increased pressure of social life and the escalating demands of work and family on Chinese professional women have prompted the need to develop themselves and excel in the same manner as their male counterparts in the workplace. Moreover, professional women have to play the roles of a good wife and devoted mother in their families. Social achievement and family responsibility have doubled the professional women’s load and role conflict between family and career. Studies conducted in the western culture have pointed out that work–family conflict is an important stressor that affects professional women’s mental health (Aryee 1992; Barnett and Hyde 2001; Lee Siew Kim and Seow Ling 2001; Parasuraman and Simmers 2001). However, most of studies on the relationship between work-family conflict and individual consequences were conducted in western culture, the link work-family conflict to depression of professional women is unclear. Unlike western workers, Chinese professional women prioritize work for family and a Chinese worker is less likely to attribute the source of interference to work because work is an important tool which is used to achieve overall benefit of family (Zhang et al. 2012). However, the finding of this study fits previous reports in the western culture and found out that work-family conflict had negative consequence, such as depression on professional women (Frone et al. 1996; Frone et al. 1997a; Thomas and Ganster 1995).

According to role theory (Byron 2005), work-family conflict occurs when role demands between work and family that are incompatible. Work-to-family conflict of professional women occurs when efforts to meet the demands of the employee role interfere with the ability to fulfill the demands of the roles as a wife, mother or care provider (Gutek et al. 1991). Conversely, family-to-work conflict may be an obstacle to successfully fulfilling work-related responsibilities and demands, thereby undermining professional women’s ability to construct and maintain a positive work-related self-image. Studies revealed that this role conflict was associated with psychological strain. Furthermore, researches points out depression, hopelessness, and other negative emotions are induced by long-term stress with invalid coping (Barnett and Hyde 2001; Peng et al. 2014; Searle et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2014a, b). Professional women lack effective means of alleviating conflicts and releasing stress when work and family fields are in a state of imbalance in the long term; their spirits are under high-strung conditions for a long time and are likely to produce various psychological barriers, including depression (Melchior, et al. 2007; Y. Peng and Mao 2015). Thus, epidemiological studies, including the current study, found that work–family conflicts are positively associated with depression (Allen et al. 2000; Hammer et al. 2005; Kinnunen and Mauno 1998). The importance of the current study is that it provides meaningful evidence for the external validity of the relationship between work–family conflict and depression in an eastern cultural setting. Given that the universal work–family conflict of professional women in the process of assuming a dual role is inevitable, the partially mediating effects of life and job satisfaction were tested and tried to provide theoretical support to protect their mental health. This study highlighted that life satisfaction and job satisfaction partially mediated the effect of work–family conflict on depression, that is, the path from work–family conflict to depression through life and job satisfaction was significant. Previous studies, including this study, indicated that work–family conflict was negatively correlated with professional women’s life satisfaction and job satisfaction (Qu and Zhao 2012; Rupert, et al. 2012; Zhao et al. 2011). Work–family conflict is often viewed as a role conflict; that is, the stresses from work and family roles are incompatible, and participating in one role would cause difficulty in getting involved in the other role (Allen et al. 2012). Individuals’ problems and responsibilities in the workplace would interfere with fulfilling family obligations; on the other hand, individuals’ problems and responsibilities in the family would interfere with completing work tasks (Kim and Hwang 2012). Role conflict would both consume individuals’ psychological capital (Floyd and Lane 2000) and reduce their performance level at home and in the workplace, inducing difficulty in obtaining affirmation from family and career and causing their exhaustion in life and at work (Gou et al. 2013; Zhao et al. 2014). Studies have also concluded that the reduction of job satisfaction and life satisfaction further resulted in depression (Piko 2006). Hence, work–family conflict, life and job satisfaction, and depression are related to each other. Findings in the present study expanded on previous research and confirmed that life and job satisfaction partially mediated the effect of work–family conflict on depression. Simultaneously investigating the trilateral relationship among the factors may create a more holistic picture of the interconnections between them. The current study showed that the paths from work–family conflict→life and job satisfaction→depression were significant and indicated that subjective well-being (i.e., life and job satisfaction) functioned as a protective factor in depression for professional women.

This viewpoint has important applications in adjusting interventions and contemporary counseling for professional women with work-family conflict. Women inevitably perform a dual role as housewives and professional women. Thus, researchers have pointed out the difficulty of identifying the approaches for reducing stress from work–family conflict and protecting professional women from depression. A strong tendency to study a positive lifestyle has been noted since Seligman indicated the intense emphasis of psychology on the negative aspects of people and the lack of attention to their positive aspects. Seligman argued that a positive psychology standpoint was necessary as humans have the remarkable ability to withstand serious setbacks and ultimately achieve adaptively in various conflict (Seligman et al. 2005). Drawing on research with individuals who have experienced a personally threatening event (e.g., work-family conflict), Taylor identified themes of the cognitive readjustment process such as effort to enhance one’s positive self-evaluations (Taylor 1983). Adaptation theory points to cognitive and emotional adaptation as well as to behavioral adaption to work-family conflict over time, all of which facilitate a return to psychological health set points (Brickman et al. 1978). The present study provided direct evidence of life and job satisfaction, which could help protect professional women’s mental health from problems such as depression. Thus, following the advocates of positive psychology and the findings from this study, professional women who suffer from work–family conflict may avert depression and maintain mental health by positively evaluating their work (and/or life) or work (and/or life) situation. This study also clarified that strengthening the positive lifestyle of professional women (i.e., job and life satisfaction) would benefit their mental health. Professional women may benefit from a positive lifestyle, a process in which individuals are trained to modify their typical attributions and positively assess their life and job to experience more positive emotions than negative ones.

Conclusions and Limitations

This study extends the current literature by directly testing the mediating effects of life satisfaction and job satisfaction on work–family conflict and depression and obtained some meaningful conclusions. The current study has demonstrated that work-family conflict positively correlated with depression for professional women. In addition, this study found out that life and job satisfaction partially mediated the effect of work–family conflict on depression in professional women. Those findings suggest that life and job satisfaction as underlying protective factors for depression in professional women with work-family conflict. However, this study also had some limitations. First, the results might be influenced by the organization culture. Even if the study sample was from several companies, the range of the study sample should be expanded in the future to enhance its external validity. Second, work–family conflict had distinct cultural characteristics. The measurement tools used in this study were from the western culture. The development of a work–family conflict scale based on the Chinese culture is necessary. Finally, this study used a cross-sectional design. The causal relationship among work–family conflict, life and job satisfaction, and depression should be cautious interpreted. Future longitudinal or experimental studies should be conducted to facilitate more causal evaluations.

Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all participants for being included in the study.

References

Ádám, S., Györffy, Z., & Susánszky, É. (2008). Physician burnout in Hungary a potential role for work—family conflict. Journal of Health Psychology, 13(7), 847–856.

Allen, T. D., Herst, D. E. L., Bruck, C. S., & Sutton, M. (2000). Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: a review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(2), 278–308. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.5.2.278.

Allen, T. D., Johnson, R. C., Saboe, K. N., Cho, E., Dumani, S., & Evans, S. (2012). Dispositional variables and work–family conflict: a meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 17–26.

Amstad, F. T., Meier, L. L., Fasel, U., Elfering, A., & Semmer, N. K. (2011). A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(2), 151.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411.

Aryee, S. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict among married professional women: evidence from Singapore. Human Relations, 45(8), 813–837.

Barnett, R. C., & Hyde, J. S. (2001). Women, men, work, and family. American Psychologist, 56(10), 781–796.

Brickman, P., Coates, D., & Janoff-Bulman, R. (1978). Lottery winners and accident victims: is happiness relative? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36(8), 917–927. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.36.8.917.

Byron, K. (2005). A meta-analytic review of work–family conflict and its antecedents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 169–198.

Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., & Williams, L. J. (2000). Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of work–family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56(2), 249–276.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

Diener, E., Inglehart, R., & Tay, L. (2013). Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Social Indicators Research, 112(3), 497–527.

Floyd, S. W., & Lane, P. J. (2000). Strategizing throughout the organization: managing role conflict in strategic renewal. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 154–177.

Frone, M. R. (2000). Work–family conflict and employee psychiatric disorders: the national comorbidity survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(6), 888–895.

Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Barnes, G. M. (1996). Work–family conflict, gender, and health-related outcomes: a study of employed parents in two community samples. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1(1), 57–69. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.1.1.57.

Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1997a). Relation of work–family conflict to health outcomes: a four-year longitudinal study of employed parents. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 70(4), 325–335. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1997.tb00652.x.

Frone, M. R., Yardley, J. K., & Markel, K. S. (1997b). Developing and testing an integrative model of the work–family interface. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50(2), 145–167.

Gierc, M., Locke, S., Jung, M., Brawley, L. (2014). Attempting to be active: Self-efficacy and barrier limitation differentiate activity levels of working mothers. Journal of Health Psychology, 1359105314553047.

Gillet, B., & Schwab, D. P. (1975). Convergent and discriminant validities of corresponding Job descriptive index and Minnesota satisfaction questionnaire scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(3), 313–317.

Gou, Y., Jiang, Y., Rui, L., Miao, D., & Peng, J. (2013). The nonfungibility of mental accounting: a revision. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 41(4), 625–633.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88.

Grzywacz, J. G., & Bass, B. L. (2003). Work, family, and mental health: testing different models of work‐family fit. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(1), 248–261.

Gutek, B. A., Searle, S., & Klepa, L. (1991). Rational versus gender role explanations for work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(4), 560–568. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.76.4.560.

Hammer, L. B., Cullen, J. C., Neal, M. B., Sinclair, R. R., & Shafiro, M. V. (2005). The longitudinal effects of work-family conflict and positive spillover on depressive symptoms among dual-earner couples. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10(2), 138–154. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.10.2.138.

He, F., Guan, H., Kong, Y., Cao, R., & Peng, J. (2014). Some individual differences influencing the propensity to happiness: insights from behavioral economics. Social Indicators Research, 119, 897–908.

Higgins, C. A., Duxbury, L. E., & Irving, R. H. (1992). Work-family conflict in the dual-career family. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 51(1), 51–75.

Hu, L. t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Kalliath, P., & Kalliath, T. (2013). Does job satisfaction mediate the relationship between work–family conflict and psychological strain? A study of Australian social workers. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development, 23(2), 91–105.

Kim, J. H., & Hwang, M. H. (2012). Gender role conflict and adolescent boys depression and attitudes toward help-seeking: the mediating role of self-concealment. Journal of Asia Pacific Counseling, 2(2), 161–160.

Kinnunen, U., & Mauno, S. (1998). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict among employed women and Men in Finland. Human Relations, 51(2), 157–177. doi:10.1177/001872679805100203.

Kong, T., He, Y., Auerbach, R. P., McWhinnie, C. M., & Xiao, J. (2014). Rumination and depression in Chinese university students: the mediating role of overgeneral autobiographical memory. Personality and Individual Differences, 77, 221–224.

Koyuncu, M., Burke, R. J., & Wolpin, J. (2012). Work-family conflict, satisfactions and psychological well-being among women managers and professionals in Turkey. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 27(3), 202–213.

Lee Siew Kim, J., & Seow Ling, C. (2001). Work-family conflict of women entrepreneurs in Singapore. Women in Management Review, 16(5), 204–221.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128.

Melchior, M., Caspi, A., Milne, B. J., Danese, A., Poulton, R., & Moffitt, T. E. (2007). Work stress precipitates depression and anxiety in young, working women and men. Psychological Medicine, 37(08), 1119–1129.

Mesmer-Magnus, J. R., & Viswesvaran, C. (2005). Convergence between measures of work-to-family and family-to-work conflict: a meta-analytic examination. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 215–232.

Ouyang, Z., Sang, J., Li, P., & Peng, J. (2015). Organizational justice and job insecurity as mediators of the effect of emotional intelligence on job satisfaction: a study from China. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 147–152.

Parasuraman, S., & Simmers, C. A. (2001). Type of employment, work–family conflict and well‐being: a comparative study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(5), 551–568.

Peng, Y., & Mao, C. (2015). The impact of person–job fit on job satisfaction: the mediator role of self efficacy. Social Indicators Research, 121, 805–813.

Peng, J., Jiang, X., Zhang, J., Xiao, R., Song, Y., Feng, X., & Miao, D. (2013). The impact of psychological capital on job burnout of Chinese nurses: the mediator role of organizational commitment. PloS One, 8(12), e84193.

Peng, J., Xiao, W., Yang, Y., Wu, S., & Miao, D. (2014). The impact of trait anxiety on self‐frame and decision making. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 27(1), 11–19.

Peng, J., Li, D., Zhang, Z., Tian, Y., Miao, D., Xiao, W., & Zhang, J. (2016). How can core self-evaluations influence job burnout? The key roles of organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(1), 50–59.

Piko, B. F. (2006). Satisfaction with life, psychosocial health and materialism among Hungarian youth. Journal of Health Psychology, 11(6), 827–831.

Plaisier, I., de Bruijn, J. G., de Graaf, R., ten Have, M., Beekman, A. T., & Penninx, B. W. (2007). The contribution of working conditions and social support to the onset of depressive and anxiety disorders among male and female employees. Social Science & Medicine, 64(2), 401–410.

Qian, L., Abe, C., Lin, T.-P., Yu, M.-C., Cho, S.-N., Wang, S., & Douglas, J. T. (2002). rpoB genotypes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing family isolates from East Asian countries. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 40(3), 1091–1094.

Qu, H., & Zhao, X. R. (2012). Employees’ work–family conflict moderating life and job satisfaction. Journal of Business Research, 65(1), 22–28.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401.

Rupert, P. A., Stevanovic, P., Hartman, E. R. T., Bryant, F. B., & Miller, A. (2012). Predicting work–family conflict and life satisfaction among professional psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(4), 341.

Schieman, S., & Glavin, P. (2011). Education and work-family conflict: explanations, contingencies and mental health consequences. Social Forces, 89(4), 1341–1362.

Schneider, H. M. (2013). Chin Angelina. Bound to Emancipate. Working Women and Urban Citizenship in Early Twentieth-century China and Hong Kong. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham [etc.] 2012. xiii, 279pp. Ill.£ 51.95. International Review of Social History, 58(02), 331–334.

Searle, A., Haase, A. M., Chalder, M., Fox, K. R., Taylor, A. H., Lewis, G., & Turner, K. M. (2014). Participants’ experiences of facilitated physical activity for the management of depression in primary care. Journal of Health Psychology, 19(11), 1430–1442.

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5), 410–421. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.60.5.410.

Stoner, C. R., Hartman, R. I., & Arora, R. (2011). Work/family conflict: a study of women in management. Journal of Applied Business Research, 7(1), 67–74.

Sznajder, K. K., Harlow, S. D., Burgard, S. A., Wang, Y.-R., Han, C., & Liu, J. (2014). Urogenital infection symptoms and occupational stress among women working in export production factories in Tianjin, China. Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction, 3(2), 142–149.

Taylor, S. E. (1983). Adjustment to threatening events: a theory of cognitive adaptation. American Psychologist, 38(11), 1161–1173. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.38.11.1161.

Thomas, L. T., & Ganster, D. C. (1995). Impact of family-supportive work variables on work-family conflict and strain: a control perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80(1), 6–15. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.80.1.6.

Wang, Y., Liu, L., Wang, J., & Wang, L. (2012). Work-family conflict and burnout among Chinese doctors: the mediating role of psychological capital. Journal of Occupational Health, 54(3), 232–240.

Wang, X., Cai, L., Qian, J., & Peng, J. (2014). Social support moderates stress effects on depression. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 8(1), 1–5.

Watson, N. L., & Weinstein, M. (1993). Pet ownership in relation to depression, anxiety, and anger in working women. Anthrozoos: A Multidisciplinary Journal of The Interactions of People & Animals, 6(2), 135–138.

Xiao, W., Zhou, L., Wu, Q., Zhang, Y., Miao, D., Zhang, J., & Peng, J. (2014). Effects of person-vocation fit and core self-evaluation on career commitment of medical university students: the mediator roles of anxiety and career satisfaction. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 8(1), 8.

Zhang, M., Griffeth, R. W., & Fried, D. D. (2012). Work‐family conflict and individual consequences. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(7), 696–713. doi:10.1108/02683941211259520.

Zhang, J., Miao, D., Sun, Y., Xiao, R., Ren, L., Xiao, W., & Peng, J. (2014a). The impacts of attributional styles and dispositional optimism on subject well-being: a structural equation modelling analysis. Social Indicators Research, 119, 757–769.

Zhang, J., Wu, Q., Miao, D., Yan, X., & Peng, J. (2014b). The impact of core self-evaluations on job satisfaction: the mediator role of career commitment. Social Indicators Research, 116(3), 809–822.

Zhao, X. R., Qu, H., & Ghiselli, R. (2011). Examining the relationship of work–family conflict to job and life satisfaction: a case of hotel sales managers. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(1), 46–54.

Zhao, X., Huang, C., Li, X., Zhao, X., & Peng, J. (2014). Dispositional optimism, self‐framing and medical decision‐making. International Journal of Psychology, 50, 121–127.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Peng, J. Work–Family Conflict and Depression in Chinese Professional Women: the Mediating Roles of Job Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction. Int J Ment Health Addiction 15, 394–406 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9736-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9736-0