Abstract

Research has not determined whether typical improvements in psychosocial functioning following self-exclusion are due to the intervention. This study aimed to explore distinctive outcomes from self-exclusion by assessing outcomes between 1) self-excluders who had and had not received gambling counselling and 2) self-excluders compared to non-self-excluders who had received gambling counselling. A longitudinal design administered three assessments on gambling behaviour, problem gambling severity, gambling urge, alcoholism, general health, and harmful consequences. Of the 86 participants at Time 1 with similar baseline scores, 59.3 % completed all assessments. By Time 2, all groups (self-excluded only, self-excluded plus counselling, counselling only) had vastly improved on most outcome measures. Improvements were sustained at Time 3. Outcomes did not differ for self-exclusion combined with counselling. Compared to non-excluders, more self-excluders abstained from most problematic gambling form and fewer had harmful consequences. Findings suggest self-exclusion may have similar short-term outcomes to counselling alone and may reduce harm in the short-term.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Self-exclusion programs remain the gambling industry’s major response to problem gambling (Blaszczynski et al. 2007; Hing and Nuske 2009). Demonstrating any distinctive outcomes of self-exclusion in assisting problem gamblers is important to its credibility and uptake. Studies have assessed program participants on program satisfaction, perceived program effectiveness, gambling behaviour, problem gambling severity, problem gambling symptomatology and negative gambling consequences. Surprisingly little research has assessed outcomes in isolation of other interventions that self-excluders may use. Many studies have included participants who have undertaken counselling, but have not distinguished their outcomes; at least one-third of excluders typically enter treatment (Bellringer et al. 2010; Cohen et al. 2011; Nelson et al. 2010; Townshend 2007). No studies have included non-excluders to isolate outcomes following self-exclusion from those associated with natural recovery or other interventions.

Research has generally found that program enrolment is followed by gambling abstinence for 25–35 % of excluders, and reduced gambling for 40–60 %, although around one-third report breaching their self-exclusion order (Cohen et al. 2011; Croucher et al. 2006; Hing and Nuske 2012; Ladouceur et al. 2000; Verlik 2008). Self-exclusion is also typically followed by reduced problem gambling severity scores, gambling urges and harms, and improvements in some aspects of quality of life (Hayer and Meyer 2011a; Ladouceur et al. 2007; Nelson et al. 2010; Tremblay et al. 2008). However, whether these outcomes are due to self-exclusion is not currently known.

Most people receiving professional, psychologically-based treatment for gambling problems benefit with abstinence or controlled gambling, irrespective of type of treatment (Pallesen et al. 2005; Productivity Productivity Commission 2010). However, Pallesen et al. (2005) recognised that Cognitive-Behaviour Therapy (CBT) was overall superior to other treatments especially where urge reduction techniques are used such as exposure. A key component of CBT is to establish stimulus control and self-exclusion arguably provides this. Positive outcomes from treatment may be due to initial urge reduction, better problem recognition allowing movement to an action stage of change, and being accountable to a third party. These same outcomes may occur amongst self-excluders. An individual’s voluntary request for self-exclusion demonstrates acceptance that their gambling is excessive and harmful, recognition of the need to take personal responsibility, and motivation to actively participate in their recovery (Blaszczynski et al. 2007); and they have made a public proclamation to not re-enter the venue(s) (Williams et al. 2012). Thus, self-excluders may be fundamentally different from non-excluders on factors that may affect their future gambling behaviour, problems and harms. A true assessment of outcomes from self-exclusion needs to compare self-excluders and non-excluders who recognise their gambling problem and are willing to take action to address it, and to control as best as possible for other interventions used.

The current study sought to overcome some previous limitations. It aimed to compare gambling behaviour, problem gambling severity, gambling urge, alcoholism, general health, and prevalence of several harmful gambling consequences between 1) self-excluders who had and had not received gambling counselling, and 2) self-excluders and non-self-excluders. A longitudinal design included three assessments approximately 6 months apart.

Previous Research on Outcomes Following Self-Exclusion

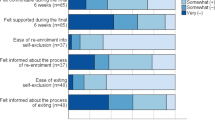

Measures gauging outcomes following self-exclusion have included gambling abstinence, breaches and participant ratings of program effectiveness. A cross-sectional study of 53 repeat self-excluders from one Canadian casino found that 36 % had returned to the casino, 50 % had gambled on other forms, and 30 % had abstained from all gambling during their previous self-exclusion period (Ladouceur et al. 2000). Also in Canada, Verlik (2008) interviewed 300 self-excluders from seven provinces. Two-thirds rated overall program effectiveness as somewhat or very effective, despite over half breaching and only 48 % of these being detected by the venue. A longitudinal study of casino self-excluders in British Columbia (Cohen et al. 2011) found that most participants were satisfied with the program. Eighteen months after self-excluding, 65 % of the retained sample (25 % of 169 participants) had never tried to gamble at the excluded casino and 35 % had completely abstained. The program connected 38 % of participants with professional treatment. Hing and Nuske (2012) assessed 36 self-excluders using a centralised service in South Australia. About 25 % had ceased gambling during the ensuing 12 months and 60 % gambled less. Of those still gambling, 35 % reported breaching, while 72 % gambled at other venues. Croucher et al. (2006) surveyed 135 self-excluders in NSW. Self-reported breaches were common (45 % of men, 33 % of women), most (about 80 %) gambled on electronic gaming machines (EGMs), and most (75 %) started gambling again within 6 months, although benefits for finances and relationships were reported. These studies suggest that breaches are moderately common, but that many participants reduce their gambling and are reasonably satisfied with the program.

Other studies have employed more sophisticated measures, recognising abstinence from all gambling may not be necessary to reduce gambling problems and harms (Nower and Blaszczynski 2008). A longitudinal study surveyed excluders from three casinos in Quebec (N = 161) six, 12, 18 and 24 (N = 53) months after exclusion (Ladouceur et al. 2007), finding significantly reduced gambling urge and increased perception of control amongst all participants. Intensity of negative gambling consequences was reduced for daily activities, social life, work and mood, as were South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) and Diagnostic & Statistical Manual-IV (DSM-IV) scores. All changes occurred in the 6 months following self-exclusion, and then plateaued. Perceived program effectiveness also declined. Also using a longitudinal design but over 12 months, Hayer and Meyer (2011a) studied casino self-excluders in several European countries. While retention rates were low (20 % of 152 at 12 months), those retained showed clear improvements in psychosocial functioning. A Tasmanian study administered a cross-sectional survey to 29 self-excluders and assessed an additional 10 excluders at the time of self-exclusion and 3 months later (Ly 2010). Both samples improved on: gambling severity, urges, frequency and duration of gambling sessions, perceived control, physical health, mental health, stress/anxiety, depressive thoughts and feelings, mood, self- confidence, social life, friendships and financial situation. These longitudinal studies suggest that self-exclusion is associated with short-term gains but questions remain over longer-term outcomes.

Nelson et al. (2010) retrospectively surveyed participants in a Missouri program 3.8 to 10.5 years after self-excluding. The vast majority (87 %) reported gambling at some point after program registration, but SOGs scores declined, spousal relationship, self-image and emotional health improved, but physical health and recreational participation decreased. Nearly 60 % of respondents undertook treatment or self-help after excluding, which was positively related to gambling abstinence and improved quality of life. Although limited by retrospective measures, this study did consider additional interventions used.

Tremblay et al. (2008) evaluated 39 participants in a self-exclusion program at a Montreal casino. Between self-exclusion and a later mandatory meeting with those wishing to end it, significant improvements were observed on time and money spent gambling, negative gambling consequences, DSM-IV scores, and psychological distress. These results confirm the benefits experienced but may be biased from only including those wanting to end their self-exclusion. In New Zealand, a small follow-up survey (Townshend 2007) of 32 people excluding within the previous 2.1 years found reduced SOGS and DSM-IV scores, less money lost, and greater self-reported control over gambling and abstinence. However, this cohort was recruited through treatment agencies, so any distinctive outcomes from self-exclusion could not be distinguished. Similarly, 69 % of participants in a New Zealand study (Bellringer et al. 2010) had contacted a help service prior to self-excluding while 68 % had done so during their self-exclusion period. Separate results were not reported for those who had and had not contacted a service.

The studies described above, although providing valuable insights into outcomes following self-exclusion, have numerous limitations. Many studies have not been peer reviewed, had small samples, were constrained to one casino, included limited outcome measures, or had substantial respondent attrition. Whether retained participants in longitudinal studies were different from those who dropped out is not known. No studies conducted comparisons with non-excluders taking alternative action to address their problem, so questions remain over whether improvements were due to self-exclusion or reflect outcomes from problem gambling recognition and a commitment to change regardless of intervention used. Several studies included respondents in treatment, so any distinctive outcomes from self-exclusion could not be isolated. The current study, although unable to overcome all of these shortcomings, used a longitudinal design that included a range of outcome measures, a sample of non-excluders, and comparisons of outcomes for self-excluders who had and had not attended counselling.

Methods

While the most rigorous design for determining cause-effect relationships between treatment and outcome is a randomised control trial (Sibbald and Roland 1998), this design was considered unfeasible for the current study due to anticipated challenges of participant recruitment, expected unwillingness to be randomly allocated to different interventions, and the need for self-exclusion to be administered by the gambling venues involved. The current study therefore used a naturalistic design to explore outcomes following participants’ choice of intervention.

Recruitment and Sampling

The original design aimed to recruit about 100 participants with reasonably equal numbers of those who had self-excluded and received gambling counselling (SE+C group), self-excluded but not received counselling (SEnoC group), and received counselling but not self-excluded (CnoSE group). Including a control group of problem gamblers but who had neither self-excluded nor received counselling was considered. However, given their need to be matched to the other groups on demographic variables, gambling behaviours and other key variables, their active recruitment was not considered feasible within the study’s time and budget constraints.

Several recruitment methods were sustained over 3 months, with 59 participants recruited through Google Adwords, 16 through gambling helplines, 13 through our research centre’s database of previous research participants consenting to be recontacted, and the remainder through flyers in counselling agencies and casino self-exclusion packs, Facebook advertising and word of mouth. A $30 shopping voucher reimbursed participants for time to complete each survey.

Seventeen self-reported problem gamblers who asked to participate had neither self-excluded nor received counselling. We initially included them as a NoSEnoC potential control group. In total, 103 problem gamblers participated in Time 1 surveys.

Procedure

The study was approved by a university human research ethics committee. Recruitment notices directed potential participants to an online registration page and screening survey to ensure recruits met inclusion criteria of residing in Queensland Australia, aged 18 years or over, and having self-excluded or received gambling counselling. Gender, age, self-exclusion and counselling status, and contact details were collected. Once registered, participants were sent an information sheet and informed consent form to sign and return and were telephoned to organise an interview time.

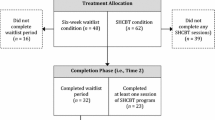

In a longitudinal design, participants were surveyed three times, approximately 6 months apart. Time 1 interviews were conducted between May–October 2012, Time 2 between January–July 2013, and Time 3 between May–October 2013. At each assessment, two researchers with counselling/social work qualifications surveyed participants by telephone.

Measures

Key measures comprised self-exclusion details (if applicable), use of professional gambling help from a variety of sources (‘yes’/‘no’), gambling frequency for nine gambling forms (‘never’ to ‘nearly every day’), most problematic gambling form, monthly gambling expenditure, gambling-related debt, perceived problem gambling severity (on a 10-point scale from ‘no problem’ to ‘severe problem’), PGSI (Ferris and Wynne 2001), Gambling Urge Scale (GUS; Raylu and Oei 2004), CAGE questionnaire for alcoholism (Ewing 1984), General Health Questionnaire (GHQ12; Goldberg and Williams 1988), Gambling Consequences Scale (adapted from Productivity Productivity Commission 1999), and basic demographic questions. Outcome measures were administered at Time 1 in relation to the 6 months before uptake of their most recent self-exclusion (SE+C group and SEnoC group) or most recent counselling consultations (CnoSE group) or the most recent 6 months (NoSEnoC group). At Times 2 and 3, measures were administered in relation to the 6 months since the previous interview.

Participants

The sample at Time 1 comprised 34 in the SE+C group (18 men, 16 women, mean age = 47), 19 in the SEnoC group (16 men, 3 women, mean age = 34), 33 in the CnoSE group (17 men, 16 women, mean age = 43), and 17 in the NoSEnoC group (7 men, 10 women, mean age = 50).

Because the study assessed a state-wide self-exclusion program (to meet funding agency requirements), it was important to include excluders from a range of venue types. Hotels, clubs and casinos operate EGMs and other forms of gambling in Queensland. Each venue individually administers the state-wide program; participants must register with each venue they exclude from. Given that 752 hotels, 493 clubs and four casinos operate EGMs in Queensland (Australasian Gaming Council 2014), it was not possible to recruit participants as they excluded. Similar reasons precluded recruiting participants as they commenced counselling. Instead, the study recruited participants who had already self-excluded and/or attended counselling. Therefore, it was important to assess the equivalence of the four groups at Time 1 to see whether any differences in outcomes at Times 2 and 3 could be reasonably associated with the different interventions used. No significant differences were found between relevant groups in terms of time since first self-exclusion or first gambling-related counselling session.

The four groups were assessed on key outcome measures at Time 1, with retrospective measures administered for the period immediately prior to uptake of self-exclusion or counselling (where relevant). No significant differences were found between the SE+C, SEnoC and CnoSE groups for monthly gambling expenditure, gambling debt, perceived problem gambling severity, or scores on the PGSI, GUS, CAGE, GHQ or Gambling Consequences Scale, demonstrating enough equivalence for valid comparisons on these measures at Times 2 and 3. The NoSEnoC group was statistically different from the other groups on most measures at Time 1, with significantly lower gambling-related debt, perceived problem gambling severity, mean PGSI score, mean GUS, and incidence of several negative gambling consequences, and higher mean GHQ score. Thus, the NoSEnoC group was surveyed only at Time 1 as it clearly was not a valid control group. Table 1 shows results for the four groups on key outcome measures at Time 1.

The groups were also compared on other possible confounding variables, including number of different gambling forms participated in, most problematic activity (EGM vs other), and frequency of gambling on most problematic activity. The only significant difference was that the number of gambling forms engaged in was significantly lower for the NoSEnoC group. There were no significant differences between any of the groups at Time 1 for most problematic form or frequency of engagement in most problematic form.

Participant Retention

As in any longitudinal research, attrition was expected. Overall, 74.4 % of participants from the SE+C, SEnoC and CnoSE groups were retained at Time 2, with 59.3 % retained at Time 3 (Table 2). The highest attrition was from the SEnoC group which also had least participants. Overall retention was higher than in previous self-exclusion studies (Cohen et al. 2011; Hayer and Meyer 2011a, b; Ladouceur et al. 2007; Steinberg 2008).

Analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS v20.0.0.2, using an alpha of 0.05. At Time 1, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.80 for the PGSI, 0.89 for GUS, 0.77 for CAGE, and 0.78 for the GHQ12. Comparative analyses attempted to isolate outcomes after self-exclusion and counselling on gambling behaviour, problem gambling and associated harms. For some measures, such as expenditure and debt, variance was large and non-parametric tests were also conducted, but as the pattern of results did not differ markedly compared to parametric tests, the latter are reported here.

Missing data due to participant attrition presented a problem for analyses, particularly due to high attrition in the SEnoC group. Analysing data using only complete cases (i.e., listwise) is usually preferable, but reduced power too much. Any form of missing data imputation was also considered inappropriate as the data would be based on small numbers and was also likely to artificially reduce standard error. Thus, for each analysis between times, we used a pairwise missing procedure and analysed the available data for each comparison. We acknowledge this as a limitation.

Analyses compared those who did and did not drop out of the study on all measures, including demographics, gambling behaviour and the other outcome measures. Those who dropped out did not differ significantly in any of the measures at Time 1 compared to those retained.

Results

Self-Exclusion Details

At Time 1, the SE+C group had self-excluded from an average of 3.71 venues (SD = 3.21, median = 3.00, range = 1–15), and SEnoC group from 2.89 venues (SD = 2.36, median = 2.00, range = 1–10). The most recent self-exclusion was still active for 82.4 % of the SE+C group and 89.2 % of the SEnoC group. Amongst the SE+C group, 32.4 % had breached their exclusion, mostly 1–2 times but up to 10 times, with 54.5 % of breachers being detected by venue staff. Only 15.8 % of the SEnoC group reported breaching, between 2 and 10 times with only one person detected.

Most Problematic Gambling Form

EGMs were the most problematic gambling form for 64.7 % of the SE+C group, 63.2 % of the SEnoC group and 84.8 % of the CnoSE group. The remainder identified their most problematic form as race or sports wagering, casino table games or card games.

Comparisons Between Self-Excluders with and Without Counselling

Before combining into a ‘self-exclusion group’ for further analysis, tests for significant differences between the SE+C and SEnoC groups were performed on all outcome variables, including harmful consequences from gambling for which adequate numbers enabled comparisons.

As noted earlier, at Time 1 these two groups were not significantly different on measures of gambling expenditure, gambling-related debt, perceived problem gambling severity, PGSI, gambling urge, CAGE, GHQ12 and harmful gambling consequences. Nor did they differ on any of these measures at Time 2, with both groups showing major and significant improvements since Time 1 on all outcome measures except CAGE. Comparisons were not conducted at Time 3 as only six SEnoC group participants were retained. Given no significant differences at Times 1 and 2, the groups were combined into a self-exclusion group (n = 53) for subsequent analyses.

Outcomes for Self-Excluders

Between Times 1 and 3, the proportion of self-excluders who reported abstaining from their most problematic gambling form increased nearly sixfold from 9.4 to 55.2 %. This substantially improved abstention rate was reflected in improvements on nearly all outcome variables (Table 3). Mean monthly gambling expenditure of $2,361 at Time 1 decreased to nearly one-sixth by Time 3 ($407). Mean gambling-related debt also declined from $18,636 to $300. Mean scores decreased from 8.8 to 3.4 for perceived problem gambling severity, from 16.9 to 5.6 on the PGSI, and from 25 to 12 on the GUS. Mean score on the GHQ12 increased from 15 to 27, indicating improved general health. Only modest changes were observed for CAGE scores.

These changes were only significant between Times 1 and 2. While excluders showed additional improvement on most measures by Time 3, these improvements were more modest and did not represent significant changes between Times 2 and 3. These results indicate that improvements experienced after self-exclusion were sustained, on average, for at least 12 months, although small sample sizes by Time 3 may mean that low statistical power prevented detection of any significant changes between Times 2 and 3.

Self-excluders showed decreased prevalence of some common negative consequences from gambling between Times 1 and 2. The prevalence of any of the consequences did not change significantly from Times 2 to 3, indicating that improvements by Time 2 were sustained at Time 3. This result should be interpreted with the limited sample size in mind. Table 4 reports results from a series of McNemar’s tests in relation to these consequences.

Comparisons Between Self-Excluders vs Non-Excluders

The preceding findings do not show that reductions in problem gambling symptoms and harm are attributable to self-exclusion, but merely demonstrate associations. Thus, outcome measures between self-excluders and non-excluders were compared. Amongst non-excluders, all had received counselling for their gambling problem, so the comparison is between respondents who had self-excluded with or without counselling and respondents who had received counselling only. All respondents had therefore acknowledged their gambling problem and taken some action to try to address it, whether through self-exclusion, counselling or both.

Two comparisons were conducted. The first compared outcomes between self-excluders and non-excluders. No significant differences were found between excluders and non-excluders at any assessment period for gambling-related debt, perceived problem gambling severity, PGSI, gambling urge, CAGE and GHQ12. Non-excluders had significantly lower monthly gambling expenditure at Time 1, t(81) = 2.15, p = 0.034, but not at Times 2 and 3. Given that Time 1 measures applied to the 6 months before uptake of exclusion or counselling, this difference cannot be attributed to these interventions. Self-excluders were significantly more likely to have abstained from their most problematic gambling form by Time 2, χ 2 (1, N = 59) = 4.27, p = 0.039 and Time 3, χ 2 (1, N = 48) = 3.88, p = 0.049, compared to non-excluders.

The second comparison was whether each group changed significantly on outcome measures between Times 1–3. Both groups changed significantly on most outcome measures between Times 1 and 2 but not between Times 2 and 3 (Tables 3 and 5). As noted earlier, the self-exclusion group improved significantly on all outcome measures except CAGE between Times 1 and 2, but not between Times 2 and 3. Table 5 shows that the non-exclusion group also changed significantly between Times 1 and 2 on monthly gambling expenditure, perceived problem gambling severity, PGSI, gambling urge and GHQ12, but not on gambling debt or CAGE. Unlike the self-exclusion group, the non-exclusion group also showed further significant improvements between Times 2 and 3 on perceived problem gambling severity and PGSI score. Group x time interactions were tested and were not statistically significant. Thus, the changes observed over time did not differ significantly for self-excluders and non-excluders. These results need to be considered according to the limitations of the sample sizes and naturalistic study design.

The same two comparisons were conducted for harmful consequences of gambling. No significant differences were found between excluders and non-excluders at any assessment period for the prevalence of each consequence within each group.

Both groups changed significantly between Times 1 and 2, but not between Times 2 and 3, in terms of the prevalence of some consequences, as examined through McNemar’s tests. Both groups experienced significant reductions between Times 1 and 2 in the prevalence of not having enough money to pay household bills, not being able to make money last from one pay day to the next, and lack of trust from those close to them. The self-exclusion group also experienced significant reductions in the prevalence of the following consequences: not having enough time to look after family’s interests; arguments with family; negative impacts on relationships with any children; putting off doing things; losing time from work; study or main role; performance at work, study or main role; borrowing money and not paying it back; and having no money to pay for rent or mortgage. Thus, the self-exclusion group experienced a significant reduction in more harmful consequences compared to the non-excluder group. Group x time interactions were tested and found to be non-significant, indicating that the change over time for self-excluders did not differ significantly compared to non-excluders. That is, while the self-exclusion group experienced a significant reduction in more harmful consequences compared to the non-exclusion group, the difference in change was not statistically significant. It is important to note that these results are considered exploratory given the small samples and unmatched design.

Discussion

One striking finding from this study is the vast improvement on most outcome measures by all groups, regardless of whether they had self-excluded only, self-excluded and received counselling, or received only counselling. These improvements occurred by Time 2 after self-exclusion and/or counselling and appeared to be sustained at Time 3, although small sample sizes may have prevented detection of changes between Times 2 and 3. These results do not show that these interventions caused these improvements given lack of a comparative group not receiving any formal intervention. However, they do align with arguments that problem acknowledgement, motivation to change, and taking action to change may account for a substantial proportion of improvements regardless of intervention type (Blaszczynski et al. 2007; Pallesen et al. 2005; Productivity Productivity Commission 2010; Williams et al. 2012). Williams et al. (2012) point out that behavioural changes observed amongst self-excluders are not fundamentally different from those observed following any form of gambling treatment. This may reflect the importance of initial urge reduction and, as such, self-exclusion may act as an important step in treatment, especially CBT. The quality of counselling received may need examination in future studies to determine whether gamblers showing greater improvements have been encouraged in similar urge reduction that may be associated with self-exclusion.

The contention that accessing any intervention, rather than type of intervention, accounts for most improvement is further supported by the current finding that addition of counselling to self-exclusion did not elevate improvements. These improvements were not due to retention of more ‘successful’ participants in the SE+C group and the CnoSE group, given that most were retained for all assessment periods, but may have inflated the extent of improvements observed. Given that less than one-third of the SEnoC group was retained for all three assessment, the outcomes of self-exclusion alone at the 12 month assessment was less clear, although the majority were retained at Time 2 when significant improvements had already occurred. Overall, results suggest that many people who undertake self-exclusion and counselling, either individually or combined, are likely to experience significant improvements in problem gambling symptomatology, general health and gambling consequences, as found in previous studies (Hayer and Meyer 2011a; Ladouceur et al. 2007; Ly 2010). Differences in any improvements between those retained and those who were not are unknown, so the ‘success’ rate of these interventions could not be established.

The results also suggest that self-exclusion may heighten improvements on some outcomes and gambling consequences beyond those experienced by gamblers who attend counselling only. Self-excluders had higher gambling abstention rates from most problematic gambling form, compared to those undertaking counselling only. This finding, while considered exploratory and requiring replication in larger studies, suggests that the external barrier over gambling that self-exclusion provides may better assist in curtailing most harmful form of gambling, compared to relying only on internal control, at least in the short term. Self-exclusion may arguably be an excellent stimulus control giving gamblers time to better manage their problem in other ways, such as finding other activities when they get an urge to gamble or having urge extinction through initial repeated exposures without gambling.

However, researchers have noted the limited therapeutic value of self-exclusion, despite its value as an external control. Blaszczynski and colleagues have criticised self-exclusion for enabling gamblers to abrogate responsibility to venues to monitor and detect breaches, which limits opportunities to enhance stress-coping abilities and may increase likelihood of relapse or use of other maladaptive coping behaviours (Blaszczynski et al. 2007; Blaszczynski et al. 2004). The Gateway to Treatment Model (Blaszczynski et al. 2007) advocates individually tailored treatment be integrated into self-exclusion programs to support participants in building internal control. O’Neil et al. (2003) argue that self-exclusion may particularly appeal to individuals with an external locus of control which may be more common amongst high frequency gamblers, although whether it has better outcomes for those with an internal or external locus of control is unclear. They conclude that self-exclusion may reduce harm from gambling, although it does not replace the need for self-responsibility to maximise therapeutic benefits. Supporting the views of Blaszczysnki et al. (2007), self-exclusion is a mechanism by which certain gamblers are able to control their gambling urge, allowing time for therapists to tailor individual formulated treatment commonly seen in CBT. Once this initial urge has been managed, even traditional medical approaches such as medication management may prove successful in maintaining reduced gambling behaviours. Nowatzki and Williams (2002) point out that the entire purpose of self-exclusion is to establish enduring external constraints for people attempting to curb their gambling, usually after internal constraints have failed. Many problem gamblers suffer from diminished internal control and, in the majority of cases, utilise self-exclusion only after experiencing marked gambling-related distress and disruption (Gainsbury 2010). Current findings suggest that self-exclusion may hasten abstinence from harmful gambling forms more than counselling alone, but additional research is needed to test this proposition.

Participants were also more likely to experience fewer harmful gambling consequences after self-exclusion compared to after counselling alone, particularly for impacts on family and work/study/main role. This finding may reflect extra time that excluders have once abstaining from most problematic gambling form. Families of problem gamblers often experience a growing sense of disconnection and isolation because of time and resources spent gambling (Grant Kalischuk 2010; Holdsworth et al. 2013; Patford 2008, 2009). Detrimental impacts of problem gambling on work are also well recognised (Productivity Productivity Commission 1999; Responsible Gambling Responsible Gambling Council 2013; Reith 2006). Both excluders and non-excluders improved in having enough money to pay for household bills and being able to make money last from one pay day to the next, suggesting that both self-exclusion and counselling may have beneficial financial outcomes. However, only the self-exclusion group improved in terms of borrowing money and not paying it back, having no money to pay for rent or mortgage, and level of gambling-related debt. Given that financial losses are the major impact of problem gambling and the source of most gambling-related harm (Neal et al. 2005; Productivity Productivity Commission 1999), any reduction in financial harm potentially reduces other negative consequences. Current findings suggest that self-exclusion may be a more rapid harm reduction measure than counselling alone, although limits associated with the sample may have confounded this result or obscured detection of other significant differences between groups. Nevertheless, this result aligns with conceptualisations of self-exclusion as a harm reduction intervention rather than one designed to address psychological processes (Blaszczynski et al. 2007; Gainsbury 2010; Williams et al. 2012).

Questions remain over outcomes following self-exclusion over the longer term, given that relapse is common amongst recovering problem gamblers (Battersby et al. 2010; Hodgins and el-Guebaly 2004). A longitudinal study found that gambling urge was a highly significant predictor of relapse (Battersby et al. 2010). Cognitive behavioural therapy and exposure therapy can help clients develop strategies to resist gambling urges, so may lead to better long-term outcomes than self-exclusion. However, the longer a person continues to engage in problem gambling, the more powerful urge becomes (Battersby et al. 2010). Self-exclusion may prompt abstinence for long enough to extinguish gambling urges. Studies with much longer timeframes are needed to test whether self-exclusion prevents relapse in the longer term.

In addition to its restricted timeframe, other study limitations need acknowledgement and can valuably inform future research. Only a modest sample was obtained which limited analyses and may have obscured meaningful between-group differences, particularly when sub-sampled by exclusion and counselling status. Larger samples would allow firmer conclusions than were possible here, particularly at Time 3 when small sample sizes may have obscured further changes on outcome measures after Time 2. Outcomes following self-exclusion could only be assessed relative to counselling and not to the absence of professional help. Absence of a control group was a major limitation, precluding comparisons with outcomes from no formal treatment.

Not all participants commenced exclusion and/or counselling at the same time. While the groups did not differ significantly on key measures at baseline, length of time between the 6 month period assessed at Time 1 and their interview at Time 2 varied amongst participants. Future research could avoid this potential limitation and use of retrospective measures at baseline by recruiting participants when they first take up self-exclusion and/or counselling. Further, obtaining matched samples by demographic characteristics would also lessen any confounds that may have occurred due to this variability. For example, the SEnoC group was predominantly young males. Because gambling pathways seem very fluid and also to some degree age- and gender-specific, the different profile of this group may have confounded results. Nevertheless, this study’s recruitment from the general population enabled self-exclusion from a wide range of venues to be assessed, unlike many previous studies.

A further limitation is that the study design did not account for other interventions, such as informal help from family and friends and self-help measures. Given wide variation in the types and quality of these supports, a challenge for future research is to include valid measures of these interventions. While retention was better than previous self-exclusion studies, some bias should be expected, especially in results for the SEnoC group which had high attrition at Time 3. Additionally, participation in the study influenced some respondents’ behaviour, with two participants self-excluding after learning about the program in the first assessment. Surveys also relied on self-report and retrospective data so are subject to recall and possible social desirability bias. The many limitations of the current study can inform better designs in future research and emphasise the need for a randomised control trial to reach definitive conclusions.

Conclusion

The results of this exploratory study suggest that self-exclusion may have similar short-term outcomes to counselling alone and may bring about more rapid gambling abstention and harm reduction, although more rigorous confirmatory research is needed. The study was unable to assess longer-term outcomes and current evidence suggests that psychological treatment may be needed to sustain long-term change. Nevertheless, given low rates of professional help-seeking amongst problem gamblers, self-exclusion appears promising in providing an important harm reduction option with at least short-term benefits for many participants, although this proposition requires further testing. Self-exclusion programs should link excluders closely with gambling treatment programs so that potential longer-terms gains from gambling treatment provide an adjunct to the shorter-term gains that appear typical after self-exclusion.

References

Australasian Gaming Council. (2014). A database on Australia’s gambling industry 2013/14. Melbourne: Australasian Gaming Council.

Battersby, M., Pols, R., Oakes, J., Smith, D., McLaughlin, K., & Baigent, M. (2010). Definition and predictors of relapse in problem gambling. Melbourne: Gambling Research Australia.

Bellringer, M., Coombes, R., Pulford, J., & Abbott, M. (2010). Formative investigation into the effectiveness of gambling venue exclusion processes in New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

Blaszczynski, A., Ladouceur, R., & Shaffer, H. (2004). A science-based framework for responsible gambling: the Reno Model. Journal of Gambling Studies, 20, 301–317.

Blaszczynski, A., Ladouceur, R., & Nower, L. (2007). Self-exclusion: a proposed gateway to the treatment model. International Gambling Studies, 7(1), 59–71.

Cohen, I. M., McCormick, A. V., & Corrado, R. R. (2011). BCLC’s voluntary self-exclusion program: Perceptions and experiences of a sample of program participants. Vancouver: BC Centre for Social Responsibility.

Croucher, J. S., Croucher, R. F., & Leslie, J. R. (2006). Report of the pilot study on the self-exclusion program conducted by GameChange (NSW). Sydney: GameChange.

Ewing, J. A. (1984). Detecting alcoholism. JAMA, the Journal of the American Medical Association, 252(14), 1905–1907.

Ferris, J., & Wynne, H. (2001). The Canadian problem gambling index: Final report. Ottawa: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse.

Gainsbury, S. (2010). Self-exclusion: A comprehensive review of the evidence. Guelph: Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre.

Goldberg, D., & Williams, P. (1988). A users guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Slough: NFER- Nelson.

Grant Kalischuk, R. G. (2010). Co-creating life pathways: problem gambling and its impact on families. The Family Journal, 18(1), 7–17.

Hayer, T., & Meyer, G. (2011a). Self-exclusion as a harm minimization strategy: evidence for the casino sector from selected European countries. Journal of Gambling Studies, 27, 685–700.

Hayer, T., & Meyer, G. (2011b). Internet self-exclusion: characteristics of self-excluded gamblers and preliminary evidence for its effectiveness. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 9(3), 296–307.

Hing, N., & Nuske, E. (2009). Assisting problem gamblers in the gaming venue: An assessment of responses provided by frontline staff, customer liaison officers and gambling support services to problem gamblers in the venue. Brisbane: Queensland Office of Gaming Regulation.

Hing, N., & Nuske, E. (2012). The self-exclusion experience for problem gamblers in South Australia. Australian Social Work, 64(4), 457–473.

Hodgins, D. C., & el-Guebaly, N. (2004). Retrospective and prospective reports of precipitants to relapse in pathological gambling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(1), 72–80.

Holdsworth, L., Nuske, E., Tiyce, M., & Hing, N. (2013). Impacts of gambling problems on partners: Partners’ interpretations. Asian Journal of Gambling Issues and Public Health, 3(11). doi:10.1186/2195-3007-3-11.

Ladouceur, R., Jacques, C., Giroux, I., Ferland, F., & Leblond, J. (2000). Brief communications: analysis of a casino’s self-exclusion program. Journal of Gambling Studies, 16(4), 453–460.

Ladouceur, R., Sylvain, C., & Gosselin, P. (2007). Self-exclusion program: a longitudinal evaluation study. Journal of Gambling Studies, 23, 85–94.

Ly, C. (2010). Investigating the use and effectiveness of the Tasmanian Gambling (Self) Exclusion Program. Hobart: Department of Health and Human Services.

Neal, P., Delfabbro, P. H., & O’Neil, M. (2005). Problem gambling and harm: Towards a national definition. Melbourne: Gambling Research Australia.

Nelson, S. E., Kleschinsky, J. H., LaBrie, R. A., Kaplan, S., & Shaffer, H. J. (2010). One decade of self exclusion: Missouri casino self-excluders four to ten years after enrolment. Journal of Gambling Studies, 26, 129–144.

Nowatzki, N., & Williams, R. J. (2002). Casino self-exclusion programmes: a review of the issues. International Gambling Studies, 2, 3–25.

Nower, L., & Blaszczynski, A. (2008). Recovery in pathological gambling: an imprecise concept. Substance Use and Misuse, 43(12–13), 1844–1864.

O’Neil, M., Whetton, S., Dolman, B., Herbert, M., Giannopolous, V., O’Neil, D., & Wordley, J. (2003). Part A—Evaluation of self-exclusion programs in Victoria and Part B—Summary of self-exclusion programs in Australian states and territories. Melbourne: Gambling Research Panel.

Pallesen, S., Mitsem, M., Kvale, G., Johnsen, B. H., & Molde, H. (2005). Outcome of psychological treatments of pathological gambling: a review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 100(10), 1412–1422.

Patford, J. L. (2008). For poorer: how men experience, understand and respond to problematic aspects of a partner’s gambling. Gambling Research, 19(1 & 2), 7–20.

Patford, J. L. (2009). For worse, for poorer and in ill health: how women experience, understand and respond to a partner’s gambling problems. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 7, 177–189.

Productivity Commission. (1999). Australia’s gambling industries. Report No. 10. Canberra: AusInfo.

Productivity Commission. (2010). Gambling, report no. 50. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Raylu, N., & Oei, T. (2004). The Gambling Urge Scale: development, confirmatory factor validation, and psychometric properties. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18(2), 100–105.

Reith, G. (2006). Research on the social impacts of gambling. Glasgow: Scottish Executive Social Research.

Responsible Gambling Council. (2013). What’s the problem with problem gambling? Toronto: Responsible Gambling Council.

Sibbald, B., & Roland, M. (1998). Understanding controlled trials. Why are randomised controlled trials important? BMJ [British Medical Journal], 316(7126), 201.

Steinberg, M.A. (2008). Ongoing evaluation of a self-exclusion program. Paper presented at the 22nd National Conference on Problem Gambling, Long Beach, California, 26–28 June.

Townshend, P. (2007). Self-exclusion in a public health environment: an effective treatment option in New Zealand. International Journal of Mental Health Addiction, 5, 390–395.

Tremblay, N., Boutin, C., & Ladouceur, R. (2008). Improved self-exclusion program: preliminary results. Journal of Gambling Studies, 24(4), 505–518.

Verlik, K. (2008). Casino and racing entertainment centre voluntary self-exclusion program evaluation. Paper presented at the 7th European Conference on Gambling Studies and Policy Issues, Nova Gorica, Slovenia, July 1–4, 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2011, from: http://www.easg.org/website/conference.cfm?id=14&cid=14§ion=PRESENTATIONS

Williams, R. J., West, B. L., & Simpson, R. I. (2012). Prevention of problem gambling: A comprehensive review of the evidence and identified best practices. Guelph: Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a Responsible Gambling Research Grant from the Queensland Department of Justice and Attorney General. Our appreciation is extended to the participants for their important and valuable involvement.

Conflict of Interest

The first and second authors have received funding support and provided consultancies to organisations directly and indirectly benefiting from gambling, including Australian governments and industry operators.

The third author has received funding support from state governments which was derived from industry sources.

The fourth author has received funding support from state governments which was derived from industry sources.

Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hing, N., Russell, A., Tolchard, B. et al. Are There Distinctive Outcomes from Self-Exclusion? An Exploratory Study Comparing Gamblers Who Have Self-Excluded, Received Counselling, or Both. Int J Ment Health Addiction 13, 481–496 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-015-9554-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-015-9554-1