Abstract

The gambling industry has offered self-exclusion programs for quite a long time. Such measures are designed to limit access to gaming opportunities and provide problem gamblers with the help they need to cease or limit their gambling behaviour. However, few studies have empirically evaluated these programs. This study has three objectives: (1) to observe the participation in an improved self-exclusion program that includes an initial voluntary evaluation, phone support, and a mandatory meeting, (2) to evaluate satisfaction and usefulness of this service as perceived by self-excluders, (3) to measure the preliminary impact of this improved program. One hundred sixteen self-excluders completed a questionnaire about their satisfaction and their perception of the usefulness during the mandatory meeting. Among those participants, 39 attended an initial meeting. Comparisons between data collected at the initial meeting and data taken at the final meeting were made for those 39 participants. Data showed that gamblers chose the improved self-exclusion program 75% of the time; 25% preferred to sign a regular self-exclusion contract. Among those who chose the improved service, 40% wanted an initial voluntary evaluation and 37% of these individuals actually attended that meeting. Seventy percent of gamblers came to the mandatory meeting, which was a required condition to end their self-exclusion. The majority of participants were satisfied with the improved self-exclusion service and perceived it as useful. Major improvements were observed between the final and the initial evaluation on time and money spent, consequences of gambling, DSM-IV score, and psychological distress. The applicability of an improved self-exclusion program is discussed and, as shown in our study, the inclusion of a final mandatory meeting might not be so repulsive for self-excluders. Future research directives are also proposed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The objective of responsible gambling measures is to prevent the development of gambling-related problems and to reduce harm associated with excessive gambling (Blaszczynski et al. 2004b). Self-exclusion is usually considered a responsible gambling measure established by the industry. The first time a self-exclusion program was used in a casino was in 1989, in Manitoba, Canada, (Nowatzki and Williams 2002). Since 1993, similar programs were introduced in other provinces of Canada, in the United-States and in many other countries. When a gambler signs a self-exclusion agreement, he tacitly agrees not to come to the casino for a specified period of time which varies from as little as one month to as long as permanently. The casino plays its part by not allowing any self-excluded gambler access to the premises or by making him leave if found on the premises. The procedures, processes and penalties associated with self-exclusion programs vary across jurisdictions. This approach to self-exclusion is more about detection than helping the self-excluders overcome their difficulties.

Recently, there have been calls for a shift in perspective on self-exclusion from a punitive, enforcement oriented process to an individual-centred focus where the emphasis is directed toward opportunities for education and rehabilitation (Blaszczynski et al. 2004a; Responsible Gambling Council 2008). Blaszczynski and his colleagues (2004a) consider self-exclusion as a gateway to complementary services and community resources. With regard to this assistance model, others suggest that a reinstatement condition should be mandatory, such as attending a responsible gambling education session before going back to the casino (Nowatzki and William 2002). This trend is gaining in popularity, but little is known about its efficiency.

Effectiveness of Self-exclusion Program

The first empirical studies were made on regular self-exclusion programs which contain neither help nor a reinstatement condition. Two evaluations of a regular self-exclusion program have shown that between 73% and 95% of self-excluders are probable pathological gamblers (Ladouceur et al. 2000; Ladouceur et al. 2007). One of these studies showed that, during the first six months, self-exclusion is link to a reduction of pathological gambling habits and gambling-related problems (Ladouceur et al. 2007). In this regard, Townshend (2007) sees self-exclusion as an efficient measure for individuals who have difficulties controlling their gambling behaviours since self-exclusion does not necessarily imply total abstinence. In fact, 70% of self-excluders report some gambling activities either in casinos or elsewhere. Furthermore, 11 to 55% of gamblers break their self-exclusion contract. The majority of self-excluders (80%), however, reported that they perceived the service positively and more than 77% revealed that they would opt for self-exclusion again, given the opportunity (Ladouceur et al. 2000, 2007). Interestingly, many gamblers criticized self-exclusion programs for not providing enough resource information on problem gambling treatment and support during the ban period (Ladouceur et al. 2000; Responsible Gambling Council 2008).

Some casinos have since integrated access to outside help (e.g. British Colombia, Quebec) or made an information session available in their self-exclusion program (e.g. Manitoba, Quebec) (for an extensive review of Canadian self-exclusion program features, see Responsible Gambling Council 2008). To date, few studies have empirically evaluated the effectiveness of an improved self-exclusion program. In Switzerland, a study was done to measure the impact of an information session on the gambling habits of at-risk gamblers before signing a self-exclusion agreement. The results indicated that attending such a session resulted in a reduction in the amount of money spent and time spent gambling (Sani et al. 2005). An information session appears to be a significant contributor in helping self-excluders. Should this information session be voluntary or mandatory? No empirical data exist concerning this question that raises interrogations and worries for users as well as for operators of gambling venues. Many think that mandatory measures could be a deterrent for entering self-exclusion (Responsible Gambling Council 2008).

The main purpose of this study is to evaluate the improved self-exclusion service offered at the Montreal casino since November 2005. In the improved procedure, the gambler has the opportunity to meet a self-exclusion counsellor at the beginning of his self-exclusion period. This counsellor is a psychologist, independent from the casino, and located outside the casino’s walls. During this meeting, the self-excluder receives detailed feedback of his gambling activities, as well as some referrals to additional resources (e.g. gambling hotlines, treatment centers, Gamblers Anonymous groups, financial counsellors). The gambler can also benefit from monthly telephone support from his counsellor for the entire duration of his agreement. This phone support, lasting for about 15 minutes, does not have a therapeutic purpose, but acts as a continual gateway toward resources to help the self-excluder respect his engagement. The Montreal self-exclusion program includes a mandatory meeting at the end of the period mentioned in the agreement. This mandatory meeting included an evaluation of the gambling situation, an information session about chance and responsible gambling and referrals to additional resources, if needed. The self-excluder must attend this evaluation and information session if he wants his self-exclusion to end. Failing to do so, the self-exclusion continues until the self-excluder does attend.

The specific goals of this study are to (1) evaluate the participation in an improved self-exclusion program that includes an initial voluntary evaluation meeting, monthly phone support, and a mandatory meeting at the end of the period covered by the agreement, (2) evaluate satisfaction and usefulness of this service, as perceived by self-excluders, (3) measure the preliminary impact of this improved program.

Method

Self-exclusion Procedure

The improved self-exclusion service has been offered in the Montreal casino since November 1, 2005. This study includes data collected from November 2005 to May 2007 inclusive. To activate his self-exclusion, a gambler contacts an information agent who then directs him to a security officer. Before signing the self-exclusion agreement, the officer asks the gambler if he would like to be put in touch with a self-exclusion counsellor for an evaluation meeting. If the gambler requests this meeting, the security officer informs him that he will be contacted by the counsellor within the next few days. In addition, the officer explains that the counsellor will contact him again one month before the end of the self-exclusion period for a mandatory final meeting. The self-excluder is told that if he does not attend this session, the self-exclusion period will continue. After having his picture taken, the gambler signs an agreement for a period of 3 months to 5 years.

The officer offers the improved agreement to any gambler who wants to self-exclude. If a gambler resists or refuses the improved self-exclusion program (e.g. if he threatens not to self-exclude because of the mandatory meeting), the officer will suggest that he sign a regular agreement. When an improved agreement is signed, the casino e-mails all the relevant information to the self-exclusion counsellor so that he can contact the gambler within the next few days. Any gambler, who does not wish to be contacted for the voluntary meeting, will be given an information sheet explaining the improved self-exclusion service. If he changes his mind, he can always contact the counsellor himself, at any time during his self-exclusion period. In all cases, a gambler has to sign an improved agreement to use any services offered by the self-exclusion counsellor. However, a gambler who has signed a regular agreement can always change his mind and sign an improved agreement, giving him access to the counsellor’s services.

Research Procedure

The first time he sees the counsellor, the self-excluder is invited to the improved program evaluation study: that is, the voluntary meeting (if applicable) or the mandatory meeting. The participant agrees, in writing, that the information collected by the counsellor may be used for research purposes. At the end of the mandatory meeting, all participants are invited to complete the service appreciation questionnaire.

Participants

Over the period of this study, 857 improved self-exclusion agreements were signed, which represents 75% of all self-exclusion agreements. Thus, 25% of the gamblers chose the regular self-exclusion contract. As of May 31, 2007, 264 self-excluders were ready for their mandatory meeting, and among these 185 mandatory meetings have been conducted. Of these 185 gamblers, 116 agreed to participate in the study and completed the service appreciation questionnaire during the mandatory meeting. Among these 116 participants, 39 participated in the voluntary meeting and 77 only participated in the mandatory meeting.

Measures

Initial Evaluation Meeting

Each initial evaluation meeting conducted by the counsellor is based on a structured clinical interview questionnaire. Research data were extracted from this questionnaire. The structured interview includes 6 sections: (1) The first section examines the motives for self-exclusion (SE), the triggers that led to this decision and various data concerning prior self-exclusions (number of prior SE, presence or absence of prior breaches of SE); (2) The second explores gambling habits before SE (frequency, time and money spent per month for each game playedFootnote 1); (3) the third section assesses the presence of pathological gambling using the DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association (APA) 1994); (4) the fourth evaluates the gambling consequences with a 0 to 5 Likert scale, ranging from no problem to severe problem; (5) the fifth discriminates between the presence or absence of depression and anxiety symptoms, and looked at alcohol use in the last 12 months; (6) the final part of the interview explores the self-excluder’s goals about gambling and the motivation to change (e.g. intention to use resources during self-exclusion, help needed with a 10 point Likert scale).

Mandatory Evaluation Meeting

Each mandatory evaluation meeting conducted by the counsellor is based on the same structured clinical interview questionnaire as the one used during the initial meeting. This questionnaire has been adapted to reflect the reference period it evaluates; some questions refer to the present time (e.g. DSM-IV, consequences, distress measures) and some go back to six months (e.g. gambling habits during SE), and a few relate to the whole SE period covered by the agreement (breaches of SE, outside help received during SE, SE efficiency). All gamblers who did not participate in the initial evaluation meeting were asked the reason why they did not want to meet with a counsellor at the beginning.

Appreciation Questionnaire

An improved self-exclusion appreciation questionnaire was developed for this study.Footnote 2 It evaluates the self-excluder’s satisfaction with the service and his perception of its usefulness. For each component of the service, the self-excluder evaluates his degree of satisfaction and his opinion on its usefulness on a scale of 1–5, ranging from not at all satisfied or useful to very satisfied or useful. The self-excluder can also choose the response “not applicable” if he is not in a position to evaluate a specific component of the service. A total of 13 statements evaluate satisfaction with the service and 16 statements measure its usefulness. The appreciation questionnaire also includes three statements that concern knowledge acquired, as well as three open-ended questions that identify (1) the components of the service that were most appreciated and least appreciated; (2) the reasons for recommending or not recommending the service to others; and (3) any suggestions for improvement.

Results

Participation in the Improved Self-exclusion Service

Data about the participation in the improved service were collected from the 857 gamblers who signed an improved agreement between November 1, 2005 and May 31, 2007.

Voluntary Evaluation Meeting

On average, 40% of the gamblers who signed an improved agreement wanted to meet with a counsellor at the beginning of their self-exclusion period. A total of 342 requests for a voluntary evaluation meeting were made. A large majority of the requests (97%) were made when signing the agreement. A few gamblers (3%), who had not made this request when signing the agreement, made the request later.

Of the 342 requests made for a voluntary initial meeting, 125 (37%) interviews were actually held. Figure 1 shows the follow-up to requests for help through a voluntary meeting, made at the beginning of the self-exclusion period.

Nearly half (44.8%) of the participants who chose not to see a counsellor for an initial meeting (those who were only seen in the mandatory meeting, n = 77) explain their choice by the fact that they did not even know about this possibility or misunderstood the service being offered. Several respondents (36.9%) noted that they did not have a gambling problem or did not need to see a counsellor at the beginning of their self-exclusion period. In 5.3% of all cases, the gamblers were already receiving help elsewhere. Various other reasons were given by 13% of participants (e.g. the fact that they had seen a counsellor in the past, that they already knew about the resources available, that they wanted to overcome their gambling problem by themselves, or that they were simply too busy).

Mandatory Meeting

Of the 264 self-excluders that were ready for their mandatory meeting as of May 31, 2007, 185 actually attended one. On average 70% of self-excluders came to the mandatory meeting, so 30% are still self-excluded. Note that 9% of self-excluders who were interviewed in a mandatory meeting renewed their self-exclusion agreement directly with the counsellor. Figure 2 below shows the follow-ups for participants ready for their mandatory meeting.

Appreciation of the Services

Seventy-nine men and 37 women (average age: 46.8 SD = 15) completed the appreciation questionnaire at the mandatory meeting. The majority (80%) of the participants were French-speaking and 71.3% were born in Canada. No significant differences were noted between the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants who took advantage of all the services offered (voluntary meeting and mandatory meeting) and those who only attended the mandatory meeting.

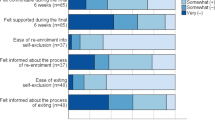

Between 73.6 and 99.1% of the participants (N = 116) reported that they were either “quite satisfied” or “very satisfied” with each component of the service. The way the service is introduced at the casino and the location of the counsellor’s office were the least appreciated components. Table 1 shows the frequency of the responses for each statement measuring satisfaction.

Gamblers found the various elements of the service to be “quite useful” or “very useful” in percentages ranging from 79.6 to 97.3%. The least useful aspect was the possibility to renew their agreement on the premises. Table 2 shows the frequency of the responses for each statement measured.

Eighty-six percent of gamblers who went to the voluntary meeting found it to be “quite useful” or “very useful” in helping them to assess their gambling habits and to identify helpful resources. The telephone support was considered by 80.5% of them to be “quite useful” or “very useful” in helping them to respect their agreement. As much as 93.8% of the total sample of gamblers who participated in the mandatory meeting considered it to be “quite useful” or “very useful” in helping them to assess their gambling habits, 81.3% found it to be “quite useful” or “very useful” in helping them to make a decision about whether or not to renew their agreement, and 90.3% reported that it was “useful” or “very useful” in motivating them to gamble more responsibly.

Over 90% of gamblers estimated that they had a better understanding of the notion of chance and false ideas, as well as a better knowledge of responsible gaming strategies, after the mandatory meeting.

Most and Least Appreciated Elements

The most appreciated elements were the counsellor’s personal qualities (e.g. his good listening skills; his calmness; his availability and his patience), the help and support offered by the counsellor (e.g., the counsellor was there to support me during difficult moments; he was there to help me), the possibility to review the participant’s gambling situation (e.g. the counsellor allowed me to refine my objectives; he showed me the state of my gambling habits) and the information given about chance (e.g. I learned a lot about games of chance; I appreciated the honesty concerning games of chance).

Eighty percent of participants did not mention any negative elements. However, when mentioned, the least appreciated aspects made reference to the content and the length of the meetings (e.g. I didn’t like being asked about the details of my passed gambling problem; the meeting was too long), the availability of the counsellor (e.g. I would have liked to have the possibility to have treatment sessions with the counsellor; the counsellor should be available 24 h a day) or the access to the premises or physical location of the premises (e.g. difficult parking; temperature of the office was uncomfortable).

Recommendations for the Service and Suggested Improvements

All respondents would recommend the service to others. Two-thirds of them did not make any suggestions for improvement. Some participants wanted improvement in the counsellor’s availability, better visibility and better explanations concerning the service, a better location for the counsellor’s office, and changing some of the content of the meetings.

Comparison Tests

Difference tests were carried out on answers given by the participants who completed all of the improved service (voluntary and mandatory meetings) and those given by participants who only attended the mandatory meeting. Chi-square tests were used for all the statements on the appreciation questionnaire.Footnote 3

For each statement, no significant difference was noted between the answers given by the two groups, except for the statement that measured the least appreciated elements of the service (χ2 (4, N = 59) = 14.72; p < 0.01). Those who benefited from all of the improved services mentioned more negative aspects than those who participated in the mandatory meeting only. The counsellor’s availability and the physical access to the premises were more often reported has being negative aspects by those who attended both meetings.

Impact of the Improved Program

Descriptive Results

Of the 39 participants who went to both meetings, 23 were males and 16 were females. Almost half (46.8%) excluded themselves for a period of 6 months, 43.6% for 12 months, 7.7% for 3 months and 2.6% for 9 months. This was the first self-exclusion contract for 19 (48.7%) of them. A fair portion of this sample (48.7%) was self-excluding for the second to the fifth time, and one gambler (2.5%) was on his 11th self-exclusion. Among those who contracted prior self-exclusions (n = 20), more than half (52.6%) mentioned having breached it in the past.

At the moment of the initial meeting, almost one-third of the participants (30.7%) said that they needed a lot or an extreme amount of help to modify their gambling habits. A quarter (23.1%) said that they had the intention of reaching out for a help resource during their self-exclusion period, while most (61.5%) did not or hesitated (15.4%) to contact such a resource. At the moment of the final meeting, 8 participants (21.1%) had, in fact, been looking for help to solve their gambling problem. Besides, participants received a mean of 3.1 (ET = 2.4) phone call supports from their self-exclusion counsellor. The majority (85.7%) of the participants did not take the initiative to call their counsellor for support during their self-exclusion period, and only 5 of them (14.3%) called at least once. Eighteen participants (46.2%) said that they breached to their self-exclusion contract by returning to the casino to gamble even though 73.7% of the participants said, during their initial meeting, that they were very or totally able to resist a strong gambling impulse. However, the majority of participants (82.1%) found the self-exclusion program to be very or totally effective for them.

Comparison Tests

Difference tests were made between measures taken at the initial and at the final meeting. Results showed a significant reduction in time, W+ = 12, n = 39, p < .0001, and money spent gambling monthly, W+ = 37, n = 39, p < .0001. The intensity of negative consequences for gambling was significantly reduced over time for social life, t = 6.4, dl = 38, p < .0001, marital or family life, t = 3.8, dl = 33, p = .0006, work, t = 2.3, dl = 29, p = .03, mood, t = 5.0, dl = 38, p < .0001, as well as financial situation, t = 5.9, dl = 38, p < .0001. Compared to the initial meeting, analyses show that less gamblers are pathological at the moment of the final meeting and that more gamblers become at-risk, χ2 = 46.1, dl = 2, p < .0001. In fact, the mean DSM-IV criteria scores dropped from 5.6 to 2.8 between the initial and the final meeting, t = 6.8, dl = 37, p < 0.0001. Also, significantly less participants have depression symptoms, χ2 = 10.7, dl = 1, p = 0.002 [exact], anxiety symptoms, χ2 = 9.0, dl = 1, p = 0.004 [exact], and an at-risk alcohol consumption, χ2 = 8.0, dl = 1, p = 0.008 [exact]. No significant differences were observed relating to suicidal ideas even though less participants reported such ideas at the final meeting compared to the initial meeting, χ2 = 1.8, dl = 1, p = 0.38 [exact]. Table 3 sums up all the difference tests.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to evaluate the new, improved self-exclusion service offered at the Montreal casino. More precisely, the objectives consisted of measuring gamblers’ participation in the improved service, evaluating users’ satisfaction and their perception of the usefulness, and measuring the impact of the improved program.

Participation in the Improved Service

A great majority of gamblers who used the self-exclusion service (75%) chose the improved program. Almost half the gamblers (40%) requested a voluntary evaluation at the beginning of their self-exclusion period. In reality, one-third of these people came to this initial meeting, which represents 15% of all the improved self-exclusion users. This level of participation with a counsellor is substantial if compared to problem gamblers in the general population and slightly more so if compared to self-excluders using a regular self-exclusion program. In fact, only 3% of problem gamblers ever seek specialized help (National Gambling Impact Study Commission 1999) and 10% of self-excluders using a regular self-exclusion program had ever met with a psychologist about their gambling problem (Ladouceur et al. 2000). Preliminary results of both meetings participants show that a quarter of all participants will initiate a therapeutic relationship for their gambling problem outside the self-exclusion context, while most participants will stick to the phone support of their self-exclusion counsellor only. Consequently, the self-exclusion counsellor can be seen as a gateway toward finding help resources as well as a complete resource in itself.

Data also indicates that almost half of the gamblers who refused the voluntary meeting did not fully understand the objective or intent of the service when they first signed the agreement. Improved training for the officers on how to introduce the service could possibly increase participation in the voluntary meeting. Another way to increase participation in the voluntary meeting would be to offer the service later in the self-exclusion process. During registration, most people are in emotional turmoil and just want to complete the process as quickly as possible (Responsible Gambling Council 2008). Therefore, gamblers would probably be more receptive to taking advantage of the initial meeting if the invitation to see a counsellor was made by the counsellor himself some days following the signature of their self-exclusion engagement. While a delay would seem to be the right method to choose, research would have to be done to evaluate the real impact of implementing such a procedure.

At the end of the self-exclusion period, more than two-thirds of the self-excluded gamblers came to the mandatory meeting. Very few reactivated their self-exclusion agreement during this meeting. Contemplating a return to gambling as a motivator to come to the mandatory meeting could, perhaps, explain this high participation rate. However, a third of the gamblers never came to the final meeting, thereby prolonging their self-exclusion agreement. Some of these gamblers are perhaps attracted to the idea of an indefinite or permanent self-exclusion period. Although the possibility of an indefinite self-exclusion is attractive, and even favourable to certain gamblers, such practice would increase the number of agreements in circulation and could risk overburdening the detection system, thereby diminishing its effectiveness (Responsible Gambling Council 2008). In order to develop and optimize the service, a more detailed examination is required to evaluate the motivators that make gamblers decide whether to come to the mandatory meeting or not.

Satisfaction and Impact of the Improved Program

Despite the mandatory aspect of the final meeting, the users were mostly satisfied with the improved service and perceived it useful when their agreement came to an end. Looking at the results, it seems quite surprising that gamblers who participated in two meetings, rather than only one, reported more negative aspects. To better understand that fact, one might keep in mind that the negative elements mentioned were related to a lack of counsellor availability. Thus, it looks like those who decided to take advantage of all the services offered expected more, hence their negative comments. Our preliminary results, about participation and satisfaction linked to a self-exclusion program including a final mandatory meeting, show a not so repulsive effect. It attenuates the general fear of including some compulsory components to a self-exclusion program (Responsible Gambling Council 2008).

Preliminary results relating to the impact of the improved service indicate many positive outcomes linked to this kind of self-exclusion program. On several variables, favourable changes resulted between the beginning and the end of the self-exclusion period. For example, important reductions were recorded on time and money spent gambling and on the intensity of the negative consequences of gambling on social, marital or family life, work, mood and financial situation. Also, major improvements were observed between the final and the initial evaluation on DSM-IV scores and on the psychological distress (reduction of depression and anxiety symptoms and reduction of at-risk alcohol use). In light of these changes, preliminary results suggest that the improved self-exclusion program had a beneficial impact.

However, some issues need to be addressed. The results about the satisfaction and efficiency of this improved program are comparable to those observed in previous studies on regular self-exclusion programs (Ladouceur et al. 2000, 2007). For now, it is difficult to distinguish whether satisfaction and improvements are due to the improved program or to any self-exclusion programs, improved or not. A comparison study with a control group (e.g. self-excluders of another casino) would allow us to isolate the effects related to the improved service. A study using a control group is currently underway at the Casino of Lac-Leamy, Hull (Canada).

Another issue is the fact that preliminary results are observed while gamblers are still under their self-exclusion contract. It is impossible to know, from these results only, if improvements and favourable perceptions will be maintained once the self-exclusion period is over. A study by Ladouceur et al. (2007) showed that gamblers whose self-exclusion period had ended, considered the self-exclusion program to be less effective or helpful than gamblers whose self-exclusion period was still active. It seems that self-exclusion creates a type of protective screen that increases the users’ appreciation of the service while they are still under self-exclusion. Our study evaluated the users’ appreciation of the service and their gambling situation while all the subjects were still benefiting from this protective screen phenomenon. Only a study tracked over time would allow us to verify how well satisfaction and improvements are maintained in the context of an improved self-exclusion program.

Finally, although there is a strong preference for the improved program, it is still unclear why some individuals decline this type of self-exclusion program. It’s possible that some gamblers see self-exclusion as a way to temporarily control their difficulties, without desiring additional support. Some use this strategy repeatedly, for short periods of time. Having to attend a mandatory meeting each time could seem useless, or even repulsive to them. Perhaps others see the improvement as an infringement on their freedom of choice. Finally, as suggested, greater visibility of the service would, perhaps, attract more users. A study targeted at the clients who refuse the improved service is being planned in order to better understand the motives behind their refusal. Currently, the regular self-exclusion program appears to be doing well alongside an improved program. This alternative allows the gambler to choose the program that he likes. It respects the responsible gaming practices philosophy, which attempts to prevent potential harm from gambling, based on informed choice (Blaszczynski et al. 2004b).

Study Limitations and Future Research

This study has certain limitations which must be taken into consideration when interpreting the results. Our preliminary sample included a small number of participants. In addition, all participants were volunteers and no random assignment was made. Also, the participant recruitment procedure did not allow solicitation of gamblers who refused to sign the improved self-exclusion program. These individuals might have a negative perception of this measure. In a future study, it would be important to examine the different characteristics of the self-excluded patrons using different programs, improved or not, and what motivated their choice. Finally, since the appreciation questionnaire used in this study is not validated, results must be interpreted cautiously.

Since self-exclusion is a relatively recent measure, some questions remain. What is the effect of each isolated element of an improved program? Does telephone support really add to an improved self-exclusion program? Could the mandatory meeting be made voluntary, without reducing the effectiveness of the service? Such questions need to be answered from an empirical perspective for society to better protect at-risk or pathological gamblers.

Notes

Frequency, time and money spent declared by the gamblers were calculated to represent a monthly period.

This questionnaire is available from the authors upon request.

The 9 statements specific to the participants who chose to have the initial voluntary meeting were excluded from those analyses. Answers falling into the “not applicable” category were also excluded.

References

American Psychiatric Association (APA). (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: APA.

Blaszczynski, A., Ladouceur, R., & Nower, J. D. (2004a). Self-exclusion: A gateway to treatment. Report prepared for the Australian Gaming Council.

Blaszczynski, A., Ladouceur, R., & Shaffer, H. J. (2004b). A science-based framework for responsible gambling: The Reno model. Journal of Gambling Studies, 20(3), 301–317. doi:10.1023/B:JOGS.0000040281.49444.e2.

Ladouceur, R., Jacques, C., Giroux, I., Ferland, F., & Leblond, J. (2000). Analysis of a casino’s self-exclusion program. Journal of Gambling Studies, 16(4), 453–460. doi:10.1023/A:1009488308348.

Ladouceur, R., Sylvain, C., & Gosselin, P. (2007). Self-exclusion program: A longitudinal evaluation study. Journal of Gambling Studies, 23, 85–94. doi:10.1007/s10899-006-9032-6.

National Gambling Impact Study Commission. (1999). Final report. Washington, Dc: Government Printing Office.

Nowatzki, R., & Williams, R. J. (2002). Casino self-exclusion programmes: A review of the issues. International Gambling Studies, 2(3–25), 3–25.

Responsible Gambling Council. (2008). From enforcement to assistance: Evolving best practices in self-exclusion. Discussion Paper by the responsible Gambling Council.

Sani, A., Carlevaro, T., & Ladouceur, R. (2005). Impact of a counselling session on at-risk casino patrons: A pilot study. Gambling Research, 17, 47–52.

Townshend, P. (2007). Self-exclusion in a public health environment: An effective treatment option in New Zealand. International Journal of Mental Health Addiction, 5, 390–395.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by grants from the Fondation Mise-sur-toi (Loto-Quebec).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tremblay, N., Boutin, C. & Ladouceur, R. Improved Self-exclusion Program: Preliminary Results. J Gambl Stud 24, 505–518 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-008-9110-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-008-9110-z