Abstract

Two experiments determined whether metamemory judgments invoking covert retrieval practice for a list of unrelated paired associate words led to the facilitation of learning a subsequent list. Three types of relation between successive lists were compared: negative transfer (A-B, A-D); a control for item-specific proactive interference (A-B, C-D); and repetition (A-B, A-B). Experiment 1 showed that the benefit of retrieval practice relative to restudying was equivalent for overt and covert retrieval in the negative transfer paradigm (A-B, A-D). Both types of retrieval minimized intrusions of first list responses in the cued recall of the second list. Experiment 2 showed that memory enhancement following covert retrieval was equivalent for new (C-D) and repeated (A-B) lists. The results are consistent with theories of the forward testing effect (FTE) that assume retrieval practice insulates subsequent learning from proactive interference and provides self-assessment feedback that may lead to more efficient encoding in future learning. Challenges in accounting for the impact of a substantial number of moderators of the FTE are reviewed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The testing effect (TE) is a phenomenon in which testing, compared to restudying or other controls, enhances memory for the original information (Chan et al., 2018; Mulligan et al., 2020; Rickard and Pan, 2017; Rowland, 2014; Sundqvist et al., 2017). Interest in the TE stems partly from its application to education as retrieval practice has been shown to increase an individual’s learning in classroom settings (Greving & Richter, 2018; Trumbo et al., 2021). The TE has been demonstrated across a wide range of materials (Yang et al., 2018), as well as across a wide range of participants (Chan et al., 2018). The forward testing effect (FTE) is a variation of the TE in which attempted retrieval of originally studied material enhances learning and memory of new material (Chan et al., 2018; Cho et al., 2017; Pastötter and Bäuml, 2014; Yang et al., 2018). The FTE may also be referred to as test-potentiated new learning (TPNL, Chan et al., 2018).

The procedure of studies examining the FTE typically involves four phases: (1) a study phase during which participants encode the stimuli comprising a first learning episode; (2) a review phase in which participants are asked to retrieve or restudy the material from the first learning episode (restudy may be replaced by a distractor task); (3) a second encoding phase in which participants encode new stimuli; and, (4) a final test phase for the material encoded during the most recent study phase. See Chan et al. (2018) for the range of FTE procedures.

During the review phase, testing can be completed in various formats (Cho et al., 2017; Endres & Renkl, 2015; Racsmány et al., 2017; Rickard and Pan, 2017; Rowland, 2014; Sundqvist et al., 2017). Central to the present experiments is the distinction between overt and covert methods of retrieval. Whereas overt retrieval requires explicit articulation (spoken or written) of the encoded material, covert retrieval requires implicit retrieval without overt articulation. One example of a covert retrieval task entails metamemory judgments of confidence about future recall success (Sundqvist et al., 2017). Several studies (e.g., Smith et al., 2013; Sundqvist et al., 2017) have found that overt and covert retrieval led to equivalent benefits in the TE paradigm where the review test and final test are on the same materials. That pattern has been demonstrated in an FTE paradigm for inductive learning of artistic styles (Lee & Ha, 2019). The present study examined the benefits of covert retrieval in the FTE paradigm where the interim and final tests are on the more typically studied verbal materials.

Metacognition may contribute to the FTE in that testing alerts participants to their level of knowledge. When that level is low, learners may adjust their encoding strategies during future learning (Chan et al, 2018; Lee & Ha, 2019). Adjustments to encoding strategies following a test may mirror encoding changes that are dependent on test expectations (Finley & Benjamin, 2012). In contrast, restudying without testing may lead to an overestimation of future memory levels due to familiarity with the to-be-learned information. That bias may preclude any motivation to change the encoding strategy. Metacognitive awareness of the level of knowledge may result from both overt and covert retrieval. Although overt retrieval is the common procedure in studies of FTE, covert retrieval is less frequently manipulated. Covert retrieval may, as does overt retrieval, draw attention to a participant’s current level of knowledge. At least two variations of covert retrieval may be instituted by researchers. Participants may be asked either to recall covertly some to-be-remembered information without any form of articulation (e.g., Sundqvist et al., 2017) or to make judgments of learning (JOLs). A JOL task requires that participants indicate their perceived likelihood of remembering the to-be-remembered information (Kubik et al., 2022).

Kubik et al. (2022) examined whether JOLs led to an FTE. Participants studied five lists of 20 words. Following the presentation of each of the first four lists of words, participants in separate groups were asked to restudy the words, complete a JOL with the presentation of the full word, complete a JOL with the presentation of word stems (the first few letters of the word), or retrieve the word given the word stem. The type of review task was constant across the four lists. All participants completed a free recall test following the fifth list. Kubik et al. (2022) found a significant FTE in recall of the fifth list for the two groups that were presented with word stems. That is, relative to restudy, retrieval to word stem cues and performing JOLs to word stems produced an FTE. In contrast, making JOLs to the entire word did not produce an FTE, a failure also reported for by Lee and Ha (2019) when both the artist and the painting were shown together for a JOL. Similarly, retrieval to word stems and JOLs to word stems led to a reduction in the number of intrusions from previous lists. Kubik et al. (2022) concluded that JOLs to incomplete cues led to retrieval processes akin to those in explicit retrieval.

One theory that may account for the similar memorial effects of overt and covert retrieval is metacognitive theory. According to metacognitive theory, testing alerts participants to their levels of knowledge leading to a change in encoding strategies moving forward (Chan et al, 2018; Lee & Ha, 2019). If both overt and covert testing alert participants to their levels of knowledge or recollection of task items, then both test formats should lead to an effective encoding strategy for subsequent learning tasks. Alternatively, if covert retrieval is a weaker barometer of one’s knowledge, then it may not be as effective as overt retrieval. As shown by Kubik et al. (2022), the effectiveness of encoding later lists may be marked by a reduction in intrusions of items from prior lists.

Although there are several theoretical accounts of the FTE (Chan et al., 2018), we focus here on two that seek to explain the reduction of intrusions from earlier learning. Release-from-proactive-interference may occur because retrieval practice creates a context change that allows participants to distinguish which items were presented in each list (Bäuml & Kliegl, 2013; Szpunar et al., 2008). Discriminating between the lists simplifies memory search as the search is restricted to the newly learned material. Alternatively, retrieval may lead to a reset-of-encoding (Pastötter et al., 2011, 2018) such that novel information is encoded without prior material coming to mind. Common to the context change and reset-of-encoding accounts is the assumption that testing serves to distinguish the successive lists in ways that mere restudy does not. Support for that assumption is gleaned from demonstrations of fewer intrusions from prior lists in the recall of the current list. Those mechanisms may be activated by both overt and covert retrieval.

The hypothesis that testing enhances distinctive representations in the learning of sequential lists echoes an explanation proposed by Tulving and Watkins (1974) in an early study of the FTE. Tulving and Watkins (1974) used a negative transfer paradigm in which a second list of word pairs comprised the stimuli from the first list paired with new words (i.e., A-B, A-D). The first list was followed by an immediate cued-recall test or a picture drawing task. The proportion of second list items recalled on an immediate test was 0.45 when the first list had been tested prior to encoding the second list and was 0.15 when the first list had not been tested. Tulving and Watkins (1974) suggested that testing insulates the learning of the second list from the interference of the first list. In the absence of testing the first list, new learning is impaired because the material from the first list competes with the material from the second list as responses to the second list are retrieved. Tulving and Watkins (1974) supported that conjecture with reference to Darley and Murdock (1971) who found higher rates of intrusions from untested lists in the learning of subsequent lists. However, Tulving and Watkins (1974) did not report the intrusion rates in their experiment. In a second experiment, Tulving and Watkins (1974) varied the effects of testing in a within-subjects design to examine whether the benefit of testing the first list was item-specific or general. They found no advantage of testing on the immediate recall of the second list when only half the items in the first list had been tested. Tulving and Watkins (1974) concluded that the benefit of testing was not item specific.

The general benefit of testing was also addressed by Cho et al. (2017) who compared the benefits of testing on old and new items. Participants studied a list of 16 Swahili-English word-pairs followed by a filler math task. During the review phase participants either completed a cued-recall test or restudied the word-pairs. Participants then studied a new list of 32 word-pairs, 16 of which were repeated from List 1 and 16 of which were completely novel. On a final test of the second list, recall was better for old than new items. However, the benefit of testing, measured as the difference between restudy and testing, was equivalent for new and old items. Those results suggest that retrieval practice benefits are general rather than specific to the items in the original list. Although Cho et al. (2017) found testing produced a general benefit on the relearning of old items and the learning of new items when pairs did not share a cue, it is unclear whether that equivalence would generalize to the negative-transfer (A-B, A-D) paradigm studied by Tulving and Watkins (1974) when pairs between the lists share the same cue. More pertinent for present purposes is whether the negative transfer paradigm would yield equivalent forward testing effects for overt and covert retrieval practice.

Kubik et al. (2022) found that covert retrieval led to an FTE when partial information about the to-be-remembered information cued the judgments of learning, but not when the entire stimulus was presented for the metamemory judgment. The present study tested the hypothesis that covert retrieval engages overt retrieval processes when the to-be-remembered information is absent. For example, a JOL made in the absence of a target may reflect the ease of implicitly retrieving the target. Whereas Kubik et al. (2022) studied the learning of single words in list, the current study of cued-recall in paired-associate learning may afford a more sensitive test of differences between the contributions of covert and overt retrieval to the FTE. We used word-pairs where the JOLs were made in the presence of only the cue word. Rhodes and Tauber (2011) found that JOLs produced a larger TE for word pairs than for single words suggesting that cued-recall may be a more sensitive test than free recall. It may be that the FTE is also dependent on whether learning involves single words or word pairs.

The aim of the first experiment reported here was to compare overt and covert retrieval in a negative transfer paradigm. This experiment was conducted for strictly exploratory reasons. The procedure differed from that in Tulving and Watkins (1974) by replacing the picture drawing task with the more typical restudy control condition. Tulving and Watkins (1974) suggested that testing insulates the second list from the interference that arises from learning a prior list with the same cues. Integration theory (Chan et al., 2018; Wahlheim, 2015) also implies that testing leads to an organization of cues and targets that minimizes interference. We tested that assumption by examining intrusion errors in which first list responses are given during cued recall of the second list. The common prediction from Tulving and Watkins (1974) and integration theory is that first list intrusions during second list retrieval would be less likely following a retrieval test of the first list. We sought to determine whether the pattern of intrusions would depend on the nature of the retrieval task (i.e., covert vs. overt). We used a between-subjects design in which participants were assigned to groups that differed in the task that followed the encoding of an initial list of word-pairs (A-B). Two groups received the A words and either recalled the B words (overt retrieval) or made a cue-only JOL (covert retrieval), JOLs were chosen as the covert retrieval task so that the researchers could ensure that participants spent the same amount of time on the overt and covert tasks, and that a response was given ensuring a greater likelihood of attention to the task. The third group received the A-B pairs for restudy. All groups then encoded a second list of word pairs comprising the cues of the first list paired with new target words (A-D) and then overtly recalled the D words in the presence of the A cue words. To address gaps in the literature, the current study included the covert, overt and restudy groups in the study of the FTE and negative transfer paradigm. Additionally, the current study analyzed intrusions of first-list response during second-list recall.

Experiment 1

Method

Participants

Tulving and Watkins (1974) tested eight participants in each group (cued recall of first list; picture drawing of first list) and reported that the effect of testing yielded t(14) = 4.97 which is equivalent to a Cohen’s d effect size of 2.66. Chan et al. (2018) reported effect sizes for several moderators of the FTE. The effect sizes of some of the moderators pertinent to the current studies were as follows: between-subjects design, 0.84; restudy as the comparison task, 0.61; and, item cued recall as the criterial task, 0.65. The Chan et al. (2018) meta-analysis led us to use a more conservative expected effect size than reported by Tulving and Watkins (1974). We set Cohen’s d = 0.50 and power = 0.80 to recruit at least 26 participants per condition. There were 121 undergraduate psychology students who participated in exchange for partial course credit. All participants provided informed consent prior to beginning the study.

Material

The stimuli consisted of 144 word-pairs derived from the English Lexicon Project (Balota, et al., 2007). The words were common concrete nouns ranging between three to five characters in length, with a Thorndike-Lorge frequency of 25 per million or greater. Proper nouns were excluded. The word-pairs were subdivided into six lists containing 20 word-pairs per list. The first list comprised A-B pairs and the second list comprised A-D pairs. Two versions of the lists were created to counterbalance items across their cue and target functions. As in Tulving and Watkins (1974), word pairs were semantically unrelated. The word-pairs were subjected to a Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA) where scores between -0.15 and + 0.15 were considered unrelated (Landauer & Dumais, 1997). The mean LSA values for Version 1 and Version 2 were 0.063 and 0.060, respectively. Appendix 1 presents the materials for Experiment 1.

Design and procedure

A single factor (Review) between-subjects design was used with three levels of review (overt test, covert test, restudy). Review refers to the task following the first list. Participants were assigned randomly to one of the three conditions and were tested in groups of four to six. Participants were informed that they were to study a list of 20 pairs of words that were followed by a black and white picture of interacting stick figures (as in Tulving & Watkins, 1974). The participants were told that, following the initial encoding period, they would be asked to complete one of four tasks: restudy the pairs; recall the targets corresponding to presented cues; judge their ability to recall the target to the presented cues; or draw the picture that had appeared at the end of the list. No participants were asked to draw the picture which served a recency buffer. Word-pairs were presented in a random order for a duration of 4 s per pair. The picture was presented for 15 s. As in Tulving and Watkins (1974), a practice trial preceded the critical trials. In the practice trial, participants were shown five word-pairs followed by examples of the possible post-list tasks. The word-pair stimuli were projected on a large screen placed at the front of the laboratory room. Stimulus presentation was programmed in PsychoPy (Peirce, 2009).

Following the presentation of the first list, participants completed a review task for 2.5 min at their own pace. In the overt retrieval condition, participants attempted to recall target words to the cue words. The cues were presented in random order and participants wrote the targets in a numbered booklet. Participants in the covert retrieval condition completed a cue-only judgement of learning (JOL) task in which they rated the likelihood that they could recall the target to the cue using a scale of 0 (completely unsure) to 100 (completely sure). Participants in the restudy condition viewed the word-pairs again. No participants were asked to draw the picture which served as a recency buffer. Following the review task for the first list, a new list of word-pairs was presented at the same rate as the first list. After the terminal picture of the second list had been presented, all participants completed a cued-recall test for the second list.

Analysis

The critical statistical analysis was a one-way between-subjects ANOVA on the mean proportion of second list target words that were recalled correctly. We also examined the number of intrusions of first list targets that were erroneously recalled as second list responses. Any target word from the first list that was incorrectly recalled as a second list target was counted as an intrusion. Analyses were carried out with SPSS 26. Alpha was set at 0.05. Pairwise comparisons were carried out as independent t-tests and were supplemented with Cohen’s d measure of effect size.

Results and discussion

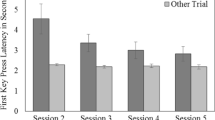

The mean proportions and standard errors for correct recall of the second list are displayed in the top section of Table 1. The ANOVA showed that the effect of Review was statistically significant, F(2, 118) = 3.37, p = 0.04, np2 = 0.05. Pairwise comparisons showed a statistically significant FTE for both overt retrieval, t(81) = 2.49, p = 0.02, d = 0.55, and covert retrieval, t(77) = 2.01, p = 0.048, d = 0.45.

To test whether retrieval in the review phase benefits memory for the second list by reducing item interference across lists, we examined the mean proportions of intrusions (i.e., recalling B targets for D targets) during second list recall. The mean intrusion proportions shown in the lower portion of Table 1 indicate that the proportion of intrusions was about 10 times higher in the restudy condition than in the retrieval conditions. The ANOVA showed that the effect of Review was statistically significant, F(2, 118) = 20.58, p < 0.001, np2 = 0.26. The post-hoc tests showed that the mean proportion of intrusions was lower following overt retrieval of the first list, t(81), = 4.70, p < 0.001, d = 1.03, and covert retrieval of the first list, t(77), = 4.56, p < 0.001, d = 1.03) than following restudy of the first list. There was no significant difference in the proportion of intrusions for the overt and covert retrieval conditions, t(78) = 0.53, p = 0.89, d = 0.03).

Experiment 1 provides a conceptual replication of the FTE in a paired-associate negative transfer paradigm where successive lists share cue words but do not share responses. Tulving and Watkins (1974) conjectured that “the interpolation of an activity requiring explicit retrieval of stored information seems to insulate the A-B list from the A-C list in a way that removes the former as an interfering component in the learning of the latter” (p. 192). Experiment 1 demonstrated that covert retrieval yields the same degree of benefit as overt retrieval and reinforced the interference explanation by showing that intrusions of first list responses in the recall of the more recent list were reduced following overt and covert retrieval.

The present results found the FTE was equivalent for repeated overt tests and switching from a covert to an overt test. These results suggest that these two types of retrieval share cognitive mechanisms that render them functionally equivalent. For example, in both the overt and covert review tests participants were presented with the cue word from the word pair. The degree of overt and covert retrieval success might provide a self-assessment of learning that leads to the development of an effective strategy for encoding the second list, consistent with metacognitive theory. Repeated study of items may thwart the accuracy of self-assessment leading to an inefficient encoding of the second list. Experiment 2 sought to examine whether the benefit of developing a more efficient metacognitive strategy is restricted to the case where successive lists overlap in content. As shown in Experiment 1, both overt and covert retrieval practice yield an FTE by reducing proactive interference. Experiment 2 was designed to determine if covert retrieval elicits an FTE when the items on the second list are completely novel. Interference effects with novel lists would be general rather than cue specific.

Experiment 2

Cho et al. (2017) claimed that the benefit of testing was independent of the relationship between items on the first and second lists. In their Experiment 1a, Cho et al. (2017) used a mixture of old and new pairs on their second list so that the second list contained twice as many items as the original list. Cued-recall performance on the second list was better for old items but the advantage of testing the first list was equivalent for old and new items. In Cho et al. (2017), the new items conformed to an A-B, C-D paradigm. The benefit of testing from a reduction in proactive interference was not assessed. We sought to compare the benefits of testing on old and new items using the between-subjects design employed in Experiment 1. The successive lists comprised either a repeated condition (A-B, A-B) or a new condition (A-B, C-D). If there is a general benefit of testing (performance on the second list is better following List 1 retrieval practice than following List 1 restudy), then the advantage should be equivalent for both types of second lists (repeat; new). Interim testing involved metamemory judgments (cue-only JOL). Because the aim of Experiment 2 was to determine the effectiveness of covert retrieval in producing an FTE when the content of the successive lists did not overlap, the overt retrieval condition was excluded. We examined first list intrusions in the A-B, C-D condition to probe for list-wise interference as did Kubik et al. (2022) for successive lists of unrelated words.

Method

Participants

Sample size was determined using the parameters of Experiment 1 (Cohen’s d = 0.50 and power = 0.80) to recruit at least 26 participants per condition. The participants were 109 undergraduate psychology students who participated in exchange for partial course credit. Participants were assigned randomly to one of the four experimental conditions defined by the crossing of Review (test; restudy) and List Relation (A-B, A-B; A-B, C-D). Participants provided informed consent prior to beginning the study.

Material and procedure

The number of word-pairs in a list was increased to 24 as we intended to avoid ceiling effects in the A-B, A-B condition. The stimuli consisted of 144 word-pairs derived from the English Lexicon Project (Balota, et al., 2007). Two versions of the pairs were created to counterbalance cue and response functions. LSA computations confirmed that the words in a pair were low in semantic relatedness. The mean LSA of Version 1 was 0.063 and the mean LSA of Version 2 was 0.061. Appendix 2 lists the word-pairs used in Experiment 2. Stimulus presentation was controlled as in Experiment 1 with one exception. In Experiment 1, participants completed the review phase and final test at their own pace within a maximum time limit. In Experiment 2, the stimuli (pairs for restudy or cues prompting retrieval) were presented at a rate of 6 s.

Design and analysis

A 2 X 2 (Review [cue-only JOL, restudy] x List Relation [A-B, A-B vs. A-B, C-D]) between-subjects design was implemented. The critical statistical analyses were a 2 × 2 ANOVA of correct final test recall, and a single factor analysis of first list target intrusions in recall of the C-D list.

Results and discussion

The mean proportion of List 2 words recalled in each of the four conditions is displayed in the upper section of Table 2. The ANOVA showed that there was a significant main effect of Review, F(1, 105) = 4.32, p = 0.04, np2 = 0.04. That main effect indicates that final recall was better for covert retrieval (M = 0.55, SE = 0.03) than for restudy (M = 0.45, SE = 0.03). There was also a significant main effect of List Relation, F(1, 105) = 4.58, p = 0.04, np2 = 0.04. Recall was better for repeated A-B word pairs (M = 0.54, SE = 0.04) than for new C-D word pairs (M = 0.41, SE = 0.04). The interaction between Review and List Relation was not statistically significant, F(1, 105) < 1. That is, as in Cho et al. (2017), the benefit of testing was equivalent for old and new items. The novel finding here is that metamemory judgments produced the pattern found by Cho et al. (2017) with overt retrieval testing.

The hypothesis that retrieval practice provides a barrier to interference was examined by comparing the probability of recalling a first list B responses during recall of the C-D list. The mean proportion of intrusions was lower for the covert retrieval condition than for the restudy condition with a medium effect size, but the difference was not statistically significant, t(54) = 1.53, p = 0.14, d = 0.42. To test further the impact of retrieval on intrusions, we compared the intrusion rates for A-D and C-D lists across experiments. For the covert retrieval condition, the difference in proportion of intrusions across lists (0.007—0.005 = 0.002) yielded a very small effect size and was not statistically significant, t(64) = 0.51, p = 0.68, d = 0.13. In contrast, for the Restudy groups, the higher rate of intrusions for the A-D list in Experiment 1 than for the C-D list in Experiment 2 (0.074—0.018 = 0.056) yielded a moderate to large effect size that was statistically significant, t(67) = 3.02, p = 0.004, d = 0.74. Covert retrieval of the first list enhanced the discriminability of responses across lists regardless of whether the cue items were shared across successive lists. The intrusion results indicate that general interference effects arising from learning a prior list are minimized by a retrieval test of the prior list. Experiment 1 and Experiment 2 were conducted separately, so it is important to take caution with interpretations of the interference results across experiments.

General discussion

The two experiments were conducted to fill gaps in the literature by comparing the benefits of overt and covert retrieval in an FTE paradigm for paired-associate learning. The relation between word pairs across lists was varied to investigate whether the magnitude of the FTE was moderated by item-specific interference. Both experiments demonstrated that metamemory judgments which lead to covert retrieval of information in one learning episode benefit the learning and memory of new information. In Experiment 1, the materials conformed to the negative transfer paradigm (A-B, A-D) used in the seminal research by Tulving and Watkins (1974). The major methodological changes included a restudy control group and a group that practiced retrieval covertly. The FTE following covert retrieval was equivalent to the FTE following overt retrieval practice. Moreover, intrusions from the first list were higher in the restudy condition than in both retrieval conditions. Those results are consistent with the hypothesis that testing insulates a current set of to-be-learned information from the proactive interference arising from previously learned information.

Ahn and Chan (2022) have argued that the negative correlation between accuracy and intrusions is not caused by testing but is a byproduct of testing. They studied lists of categorized words where the semantic relationship between the final and prior lists was varied under the assumption that the degree of proactive interference would modulate the size of the FTE. Ahn and Chan (2022) found that whereas the number of intrusions was affected by inter-list semantic similarity, the FTE was independent of the level of proactive interference across lists. A conceptually similar manipulation of levels of proactive interference occurred across the current experiments that differed in whether the cues in successive lists were identical (A-B, A-D) or different (A-B, C-D). For the restudy condition, recall was higher for the C-D list and intrusions were higher for the A-D lists. Metamemory judgments led to equivalent levels of intrusions for the two lists although recall was higher for the C-D list. That is, testing removed the negative correlation between recall and intrusions. The critical benefit of testing, according to Ahn and Chan (2022), stems from the semantic organization among items induced by testing. However, it is not clear how semantic organization would operate on the unrelated materials used in the present study.

Chan et al. (2018) noted the importance of the materials as a moderator of the FTE. Variations among materials may account for the inconsistency across studies that have compared overt and covert retrieval in studies of the standard TE. Smith et al. (2013) found equivalent benefits of the two types of retrieval format, but Tauber et al. (2018) found no benefit from covert retrieval practice. There were several differences in design and procedure between those studies including the type of material that was learned. Whereas Smith et al. (2013) tested categorized word lists, Tauber et al. (2018) tested definitions of psychology terms. The differences in types of material may also constrain the type of criterial test, another moderator of the FTE (Chan et al., 2018). It remains to determine whether the semantic relationship among items limits the benefit of covert retrieval in the negative transfer paradigm.

Chan et al. (2018) reported a meta-analysis of FTE studies and review a range of theoretical accounts of the FTE. The class of explanations that was most strongly supported by the meta-analysis was integration theory. Integration theory predicts that a relationship between original and new learning that reminds the learner of original learning during new learning enhances the FTE. Consistent with integration theory, we found an FTE for the A-D list with a reduction of intrusions in the A-D following a review phase that engaged retrieval processes. A similar result was reported by Wahlheim (2015) although that study included a C-D list where there was no FTE for C-D items and no benefit of testing for repeated items.

There were many procedural differences between the present study and Wahlheim (2015). Among the major methodological differences were the following features in Wahlheim (2015): the words in the A-B pairs (e.g., pearl – harbor) and A-D pairs (e.g., pearl – jewelry) were semantically related (although the B and D words were unrelated to each other); testing and restudy were varied within-subjects in a list of 60 pairs; the type of pairs (A-B; A-D; C-D) were mixed on the second list of 90 pairs, and, participants judged whether a pair recalled on the second list had changed from the prior list. Wahlheim (2015) hypothesized that the FTE for A-D items depends on whether participants recollect a change in the responses from the original A-B pairing. Change recollection was better for tested items than restudied items. When recall of the second list was conditionalized on change recollection, A-D performance was better than C-D performance (i.e., proactive facilitation) and the FTE was eliminated.

In the present studies, the word pairs were unrelated, the type of review was varied between-subjects, and the relation between the original and second lists was varied between-subjects. The A-D change would be noted by all participants as the relationship between lists was highlighted during the practice trials that preceded the critical experimental trials. Therefore, it is unclear why there was no proactive facilitation in the current studies. It may be that related items would yield proactive facilitation if testing enhances the connectivity of the cue to pre-experimentally associated responses. Alternatively, it may that the within-subjects manipulation of review type is critical for bolstering the recall of A-D items. During encoding of the first list, within-subjects variation of the review factor (test vs. restudy) may lead to extra rehearsal of tested items during the presentation of restudy items (Carpenter et al., 2006; Mulligan et al., 2020). That extra rehearsal may contribute to improved change recollection. Rehearsal borrowing could not occur when review type is manipulated between-subjects.

The within-subjects manipulation of testing in Wahlheim (2015) was intended to provide a comparison with the within-subjects manipulation in Experiment 2 of Tulving and Watkins (1974). Tulving and Watkins (1974) found that there was no FTE for their within-subjects design leading them to conclude that the benefit of testing is not-item specific but rather requires testing of an entire list. Wahlheim (2015) hypothesized that change detection is item-specific so that a testing effect should occur in the within-subjects design. Wahlheim (2015) noted that there were several procedural differences from Tulving and Watkins (1974) and underscored the discrepancy in semantic relationship among word pairs as well as the proportion of words that were carried over across lists. Other potentially important differences included the absence of a restudy condition in Tulving and Watkins (1974). Rather, the first list contained 24 pairs of words and 12 were tested with cued recall. None were restudied. Following the subsequent 24-item A-D list, 6 of the previously tested items and 6 of the non-tested items were tested with cued-recall. No difference was found in the accuracy of recall for tested and non-tested items. That result suggests that the benefit of testing in their first experiment is dependent on testing the entire list.

Another critical difference between the Wahlheim (2015) and Tulving and Watkins (1974) within-subjects studies is that Tulving and Watkins (1974) included a third phase of testing in which the A words for each of the 24 pairs were presented and participants were asked to recall both the B and D responses, a procedure known as modified modified free recall (MMFR). Although the MMFR test followed the immediate recall test of the second list, it may be vital to the results given that participants had been informed that there would be an MMFR test following the immediate second list test as it was included in the practice trials preceding the main experiment. Thus, participants would be motivated to try to remember the original B responses during A-D learning. Anticipation of the MMFR test has been shown to be a limiting factor in second list cued-recall performance in the negative transfer paradigm (Allen & Arbak, 1976).

The diversity of manipulations that govern the magnitude of the FTE is substantial. Chan et al. (2018) categorized the studies of their meta-analysis as falling into one of four research paradigms. The standard paradigm is the one followed in the current studies: material is learned; it is tested or not; new material is studied; the new material is tested. Whereas studies that adhered to the standard paradigm yielded a mean effect size of 0.75, the entire set of studies in the meta-analysis yielded a mean effect size of 0.44. Similarly, the impact of moderators depends on the procedure. For example, there is a stark contrast in the effect size of the FTE for paired associate learning across procedures: for studies following the standard procedure the effect size is 0.69; for the complete set of studies the effect size is 0.04. When planning studies of the FTE, researchers should account for the influence of the specific procedures and materials.

We have shown that meta-memory judgments which entail covert retrieval yield comparable effect sizes to the FTE following overt review testing in the negative transfer paradigm. Covert retrieval also produces a testing benefit for repeated pairs and for pairs bearing neither a cue nor response identity to those in initial learning. The benefits of testing may arise via several mechanisms depending on the relationship between successive learning episodes. Those mechanisms may capitalize on item-specific information to reduce proactive interference and/or they may enhance the efficiency of encoding during later learning episodes. For example, covert testing affords a self-assessment that informs the learner of the proficiency of their default mode of encoding. In the instructional arena, educators should design interim testing methods tailored to the type of material and form of criterial tests. As suggested by the procedures introduced in Tulving and Watkins (1974), providing learners with a preview of the type of material and nature of criterial tests may be a decisive determinant of maximizing the benefits of interim testing.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, MC, upon reasonable request.

References

Ahn, D., & Chan, J. C. K. (2022). Does testing enhance new learning because it insulates against proactive interference? Memory & Cognition. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-022-01273-7

Allen, G. A., & Arbak, C. J. (1976). The priority effect in the A-B, A-C paradigm and subjects’ expectations. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 15(4), 381–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(76)90033-5

Balota, D., Yap, M., Cortese, M., Hutchison, K., Kessler, B., Loftis, B., Neely, J., Nelson, D., Simpson, G., & Treiman, R. (2007). The English lexicon project. Behavior Research Methods, 39(3), 445–459. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193014

Bäuml, K.-H.T., & Kliegl, O. (2013). The critical role of retrieval processes in release from proactive interference. Journal of Memory and Language, 68, 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2012.07.006

Carpenter, S. K., Pashler, H., & Vul, E. (2006). What types of learning are enhanced by a cued recall test? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 13(5), 826–830. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03194004

Chan, J., Meissner, C., & Davis, S. (2018). Retrieval potentiates new learning: A theoretical and meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 144(11), 1111–1146. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000166

Cho, K. W., Neely, J. H., Crocco, S., & Vitrano, D. (2017). Testing enhances both encoding and retrieval for both tested and untested items. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 70(7), 1211–1235. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2016.1175485

Darley, C. F., & Murdock, B. B. (1971). Effects of prior free recall testing on final recall and recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 91(1), 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0031836

Endres, T., & Renkl, A. (2015). Mechanisms behind the testing effect: A empirical investigation of retrieval practice in meaningful learning. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01054

Finley, J. R., & Benjamin, A. S. (2012). Adaptive and qualitative changes in encoding strategy with experience: Evidence from the test-expectancy paradigm. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 38(3), 632–652. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026215

Greving, E., & Richter, T. (2018). Examining the testing effect in university teaching: Retrievability and question format matter. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02412

Kubik, V., Koslowski, K., Schubert, T., & Aslan, A. (2022). Metacognitive judgments can potentiate new learning: The role of covert retrieval. Metacognition and Learning, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-022-09307-w

Landauer, T. K., & Dumais, S. T. (1997). A solution to Plato’s problem: The latent semantic analysis theory of acquisition, induction, and representation of knowledge. Psychological Review, 104, 211–240. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.104.2.211

Lee, H. S., & Ha, H. (2019). Metacognitive judgments of prior material facilitate learning new material: The forward effect of metacognitive judgments in inductive learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(7), 1189–1201. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000339

Mulligan, N. W., Buchin, Z. L., & West, J. T. (2020). Assessing why the testing effect is moderated by experimental design. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 46(7), 1293–1308. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000787

Pastötter, B., & Bäuml, K. T. (2014). Retrieval practice enhances new learning: The forward effect of testing. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00286

Pastötter, B., Schicker, S., Niedernhuber, J., & Bäuml, K.-H.T. (2011). Retrieval during learning facilitates subsequent memory encoding. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition, 37, 287–297. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021801

Pastötter, B., Engel, M., & Frings, C. (2018). The forward effect of testing: Behavioral evidence for the reset-of-encoding hypothesis using serial position analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1197. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01197

Peirce, J. W. (2009). Generating stimuli for neuroscience using PsychoPy. Frontiers in Neuroinformatics, 2(10), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.11.010.2008

Racsmány, M., Szőllősi, Á., & Bencze, D. (2017). Retrieval practice makes procedure from remembering: An automatization account of the testing effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. Advance online publication, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1037/xlm0000423

Rhodes, M. G., & Tauber, S. K. (2011). The influence of delaying judgments of learning on metacognitive accuracy: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 137(1), 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021705

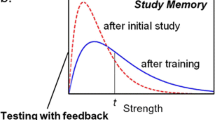

Rickard, T. C., & Pan, S. C. (2017). A dual memory theory of the testing effect. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-017-1298-4

Rowland, C. A. (2014). The effect of testing versus restudy on retention: A meta-analytic review of the testing effect. Psychological Bulletin, 140(6), 1432–1463. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037559

Smith, M. A., Roediger, H. L., III., & Karpicke, J. D. (2013). Covert retrieval practice benefits retention as much as overt retrieval practice. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 39(6), 1712–1725. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033569

Sundqvist, M. L., Mäntylä, T., & Jönsson, F. U. (2017). Assessing boundary conditions of the testing effect: On the relative efficacy of covert vs. overt retrieval. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01018

Szpunar, K. K., McDermott, K. B., & Roediger, H. L. (2008). Testing during study insulates against the buildup of proactive interference. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and cognition, 34(6), 1392–1399. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013082

Tauber, S. K., Witherby, A. E., Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Putnam, A. L., & Roediger, H. L., III. (2018). Does covert retrieval benefit learning of key-term definitions? Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 7(1), 106–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2016.10.004

Trumbo, M. C. S., McDaniel, M. A., Hodge, G. K., Jones, A. P., Matzen, L. E., Kittinger, L. I., Kittinger, R. S., & Clark, V. P. (2021). Is the testing effect ready to be put to work? Evidence from the laboratory to the classroom. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 7(3), 332–355. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000292

Tulving, E., & Watkins, M. J. (1974). On negative transfer: Effects of testing one list on the recall of another. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 13, 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(74)80043-5

Wahlheim, C. N. (2015). Testing can counteract proactive interference by integrating competing information. Memory & Cognition, 43(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-014-0455-5

Yang, C., Potts, R., & Shanks, D. R. (2018). Enhancing learning and retrieval of new information: A review of the forward testing effect. NPJ Science of Learning, 3(8). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-018-0024-y

Funding

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Monique Carvalho, Harvey Marmurek; Data curation: Monique Carvalho, Alysha Cooper; Formal analysis and investigation: Monique Carvalho, Alysha Cooper, Harvey Marmurek; Methodology: Monique Carvalho, Alysha Cooper, Harvey Marmurek; Project administration: Monique Carvalho, Harvey Marmurek; Writing – original draft preparation: Monique Carvalho; Writing—reviewing and editing: Harvey Marmurek; Supervision Harvey Marmurek.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Declaration of Interest

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Competing Interests

The authors of this paper have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Carvalho, M., Cooper, A. & Marmurek, H.H.C. Covert retrieval yields a forward testing effect across levels of successive list similarity. Metacognition Learning 18, 847–861 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-023-09348-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-023-09348-9